Abstract

Histone acetylation is an extensively investigated post-translational modification that plays an important role as an epigenetic regulator. It is controlled by histone acetyl transferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). The overexpression of HDACs and consequent hypoacetylation of histones have been observed in a variety of different diseases, leading to a recent focus of HDACs as attractive drug targets. The natural product largazole is one of the most potent natural HDAC inhibitors discovered so far and a number of largazole analogs have been prepared to define structural requirements for its HDAC inhibitory activity. However, previous structure–activity relationship studies have heavily investigated the macrocycle region of largazole, while there have been only limited efforts to probe the effect of various zinc-binding groups (ZBGs) on HDAC inhibition. Herein, we prepared a series of largazole analogs with various ZBGs and evaluated their HDAC inhibition and cytotoxicity. While none of the analogs tested were as potent or selective as largazole, the Zn2+-binding affinity of each ZBG correlated with HDAC inhibition and cytotoxicity. We expect that our findings will aid in building a deeper understanding of the role of ZBGs in HDAC inhibition as well as provide an important basis for the future development of new largazole analogs with non-thiol ZBGs as novel therapeutics for cancer.

Graphical Abstract

The overexpression of HDACs and consequent hypoacetylation of histones have been observed in a variety of different diseases, leading to a recent focus of HDACs as attractive drug targets. The natural product largazole is one of the most potent natural HDAC inhibitors discovered so far. To probe the effect of various zinc-binding groups (ZBGs) on HDAC inhibition. we prepared a series of largazole analogs with various ZBGs and evaluated their HDAC inhibition and cytotoxicity.

INTRODUCTION

Epigenetics is the study of gene expression changes not caused by variations in the DNA sequence, but rather by enzyme-mediated chemical modifications.1 DNA is tightly compacted in the nucleus in a complex known as chromatin, which is comprised of many nucleosomes. Each nucleosome contains about 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of four histone core proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4). By chemically modifying either the DNA or the histones, the chromatin architecture can be perturbed, and consequently, gene expression can be altered. These chemical modifications are controlled by three classes enzymes, categorized as ‘writers’, ‘erasers’, and ‘readers’. ‘Writers’ are responsible for the incorporation of epigenetic marks into DNA or histones, while ‘erasers’ remove them. This dynamic equilibrium of incorporating and removing epigenetic markers from DNA and histones forms an epigenetic code, which is recognized by enzymes called ‘readers’. ‘Readers’ contain recognition domains for specific epigenetic marks, and subsequently affect gene expression. Deregulation of epigenetic mechanisms has been linked to a variety of disorders including cancer, immunodeficiency, and learning disabilities.

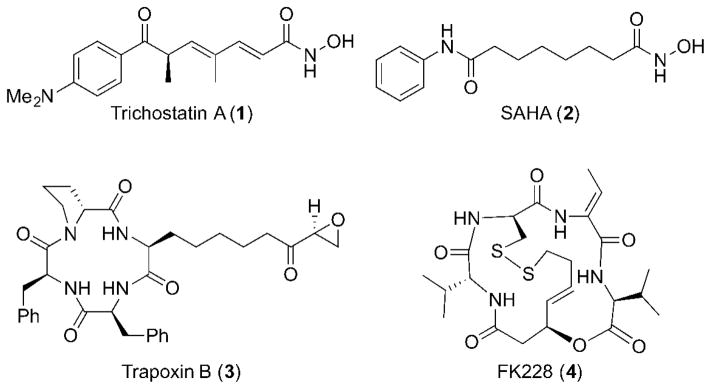

There are several post-translational histone modifications that play important roles as epigenetic regulators. Among them, histone acetylation is one of the most extensively investigated epigenetic marks.2 It has garnered considerable interest due to its implications in early stages of tumorigenesis and cancer progression. The acetylation state of histones is controlled by histone acetyl transferases (HATs, ‘writers’) and histone deacetylases (HDACs, ‘erasers’). HATs transfer acetyl groups to the ε-amino group of lysine residues on histone tails by utilizing acetyl-CoA as a cofactor. The uncharged lysine residue has reduced interactions with the negatively charged DNA backbone, resulting in euchromatin states, and a consequent increase in gene transcription. HDACs remove the acetyl groups, restore the positive charge of the amino group, forming heterochromatin states, which increases interaction with the DNA backbone, and represses gene expression. The overexpression of HDAC activity and consequent hypoacetylation of histones has been observed in a variety of different diseases, which has recently made HDACs attractive drug targets. The significance of HDACs in several disease states, especially in various types of cancers, as well as normal physiological functions has led to the discovery and development of a number of HDAC inhibitors, such as trichostatin A (1), suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (2, SAHA), trapoxin B (3), and FK228 (4) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative HDAC inhibitors.

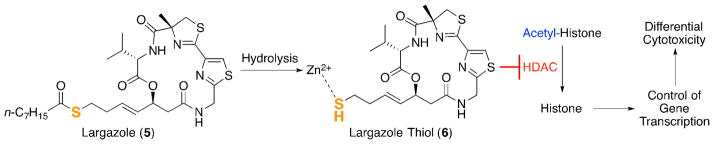

The cyclic depsipeptide largazole (5, Figure 2) isolated from a cyanobacterium of the genus Symploca (re-identified as a new genus, Caldora penicillata) is a marine natural product with a novel chemical scaffold.3 Largazole (5) drew initial interest due to its highly differential growth-inhibitory activity, preferentially targeting transformed over non-transformed cells.3a Cell type specific rather than general cytotoxic effects were later supported by the NCI 60-cell line screen.4 The combination of unique structural features and interesting biological activity has made largazole (5) a very attractive target for both synthetic and chemical biology groups alike.5

Figure 2.

The mechanism of action of largazole (5).

The strong interest in the synthetic community has resulted in 13 total syntheses,5–6 including our first total synthesis of largazole (8 steps, 19% overall yield).6a We also demonstrated that the mechanism of action relevant for the anti-proliferative activity of largazole is indeed mediated by the inhibition of HDACs that utilize Ac-H3 (Lys9/14) as a substrate (Figure 2). The same finding was independently reported by the Williams group.6c A real visualization of the interaction with HDAC8 was achieved by Christianson and co-workers, who reported the X-ray crystal structure of HDAC8 complexed with largazole thiol 6.7 Following the completion of the total synthesis and molecular target identification of largazole, a number of largazole analogs have been prepared to define the pharmacophore and structural requirements for the HDAC inhibitory and antiproliferative activities of largazole.4–5,6i,6j,6l,6m,8 While previous structure–activity relationship studies have heavily investigated the role of the macrocycle region in HDAC inhibition as well as cytotoxicity against various cancer cell lines, there have been only limited efforts to probe the effect of Zn2+-binding affinities on HDAC inhibition. For example, we prepared the hydroxy analog of largazole to show that the thiol group is the warhead of largazole that binds Zn2+ in the active site of HDACs.6a Tillekeratne and co-workers prepared largazole analogs with modification of the metal-binding domain by introducing a second heteroatom in the side chain two to three atoms apart from sulfur.6m These analogs were expected to interact with Zn2+ via a five- or six-membered cyclic transition state, but they were less potent than largazole (5). Herein, we report the design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of several zinc-binding group (ZBG) analogs of largazole. Building a deeper understanding of the role of ZBGs in HDAC inhibition as well as the ability to utilize non-thiol ZBGs will aid in the development of largazole into a more efficient molecular probe and anti-cancer therapeutic.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design of largazole ZBG analogs

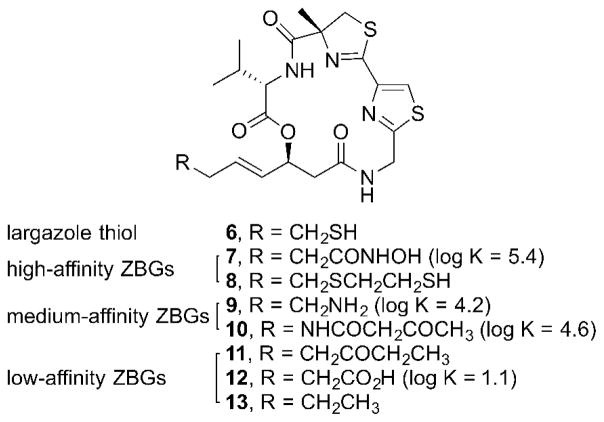

In order to fully assess the importance of the ZBG in HDAC inhibition, several ZBGs spanning a wide range of Zn2+-binding affinity were chosen to be incorporated into the largazole scaffold (Figure 3).9 One of the highest affinity ZBGs that have been reported are hydroxamic acids with an association constant (log K) of 5.4. The hydroxamic acid is prevalent in many other HDAC inhibitors, such as trichostatin A (1) and SAHA (2) (Figure 1). The mercaptosulfide was another high-affinity ZBG that we chose. While the Zn2+-binding affinity of mercaptosulfides has not been experimentally measured, mercaptosulfides are widely used in inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), which are a family of Zn2+-dependent endopeptidases.10 An amine and a β-ketoamide, which have log K values of 4.2 and 4.6 respectively, were chosen as medium-affinity ZBGs. For low-affinity ZBGs, an ethyl ketone, as seen in natural product HDAC inhibitor apicidin A, and a carboxylic acid, as seen in natural product HDAC inhibitors azumamides C and E, were chosen.8a Carboxylic acids have a log K value of 1.1, and while no log K value for ketones has been reported to date, they are generally considered very weak Zn 2+-binders. Lastly, a simple alkyl chain was chosen to probe the effect of completely removing the ZBG.

Figure 3.

Structure of largazole thiol (6) and ZBG analogs 7–13.

Chemistry

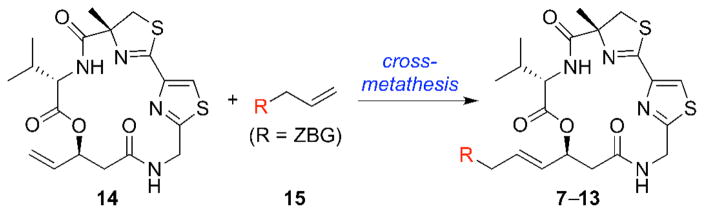

Initially, we had envisioned a quick access to all of these analogs in a divergent manner by utilizing a cross-metathesis (CM) reaction of the known late-stage macrocyclic intermediate 146a with the appropriate ZBG-containing alkene 15 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

An initial synthetic approach to largazole ZBG analogs 7–13.

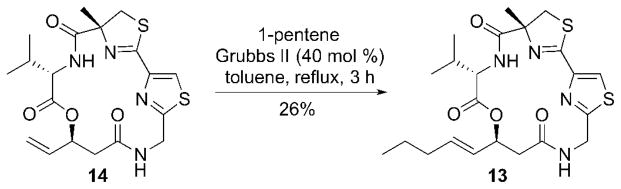

This approach proved successful for the synthesis of alkyl analog 13 (Scheme 1). The CM reaction of 14 with 1-pentene in the presence of Grubbs II catalyst afforded the desired alkyl analog 13, albeit in low yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the alkyl analog 13.

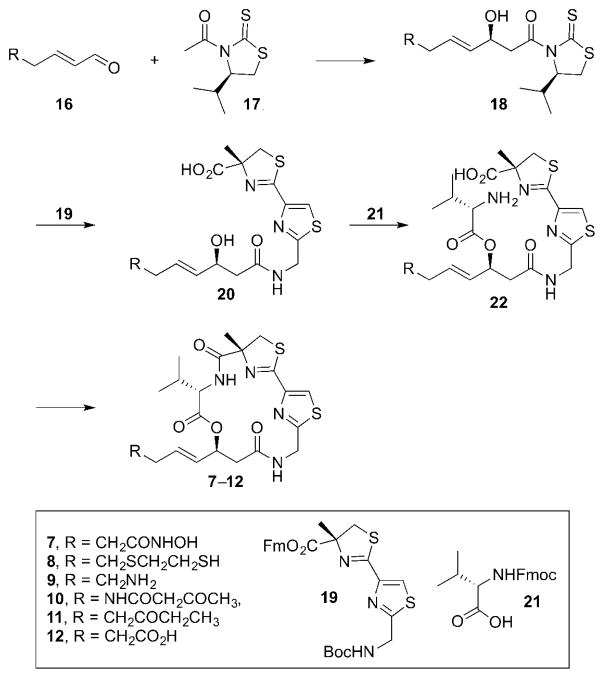

While we were able to access the desired product in the case of 13 via the CM approach, all other substrates that were subjected to the CM reaction with 14 did not result in any desired CM product due to the potential coordination of a ZBG to Grubbs II catalyst.6a,6b Modulation of catalyst, catalyst loading, and solvent failed to produce the desired analog in all cases. In order to overcome this issue, for the remaining analogs, the corresponding ZBGs were incorporated by preparing various syn-aldol products (18) (Figure 5). They could then be coupled with common intermediates 19 and 21 to prepare the desired analogs 7–12.

Figure 5.

A revised synthetic approach to largazole ZBG analogs 7–12.

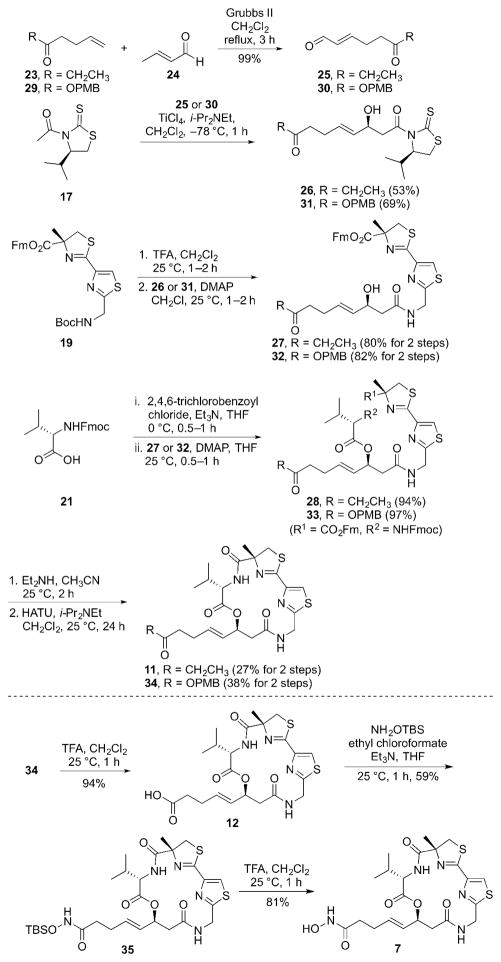

For the preparation of the ketone analog 11, the synthesis began with the CM reaction of the known ethyl ketone 2311 and crotonaldehyde (24) to afford the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 25 (Scheme 2). The subsequent asymmetric aldol reaction of 25 with N-acetyl thiazolidinethione (17) resulted in the syn-aldol product 26, which was coupled to the known thiazole-thiazoline 198j to afford the β-hydroxy amide 27. Compound 27 was subjected to Yamaguchi esterification conditions with the commercially available N-Fmoc-L-valine (21) to produce the substrate 28 for macrolactamization. The Fm/Fmoc-deprotection and HATU-mediated macrolactamization of 28 completed the synthesis of the ketone analog 11.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the ketone analog 11, carboxylic acid analog 12, and hydroxamic acid analog 7.

The carboxylic acid analog 12 was prepared in a similar fashion by utilizing the appropriate syn-aldol product (Scheme 2). The CM reaction of the known PMB ester 2912 and crotonaldehyde (24) afforded the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 30. The asymmetric aldol reaction of 30 with 17 resulted in the syn-aldol product 31, which was coupled to 19 to afford the β-hydroxy amide 32. Compound 32 was subjected to Yamaguchi esterification conditions with 21 to give the acyclic precursor 33. The Fm/Fmoc-deprotection and HATU-mediated macrolactamization of 33 afforded the PMB-protected macrocycle 34. The final PMB-deprotection completed the synthesis of the carboxylic acid analog 12.

The carboxylic acid analog 12 was then further elaborated to install the hydroxamic acid moiety. The coupling of 12 with TBS-protected hydroxylamine in the presence of ethyl chloroformate followed by TFA-mediated TBS-deprotection afforded the desired hydroxamic acid analog 7 (Scheme 2).

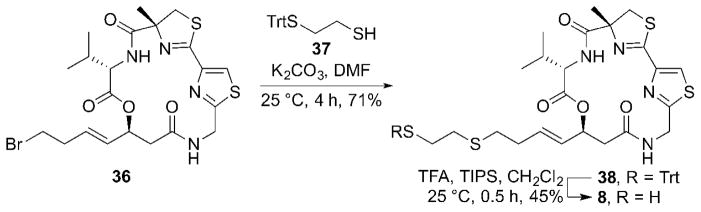

In order to prepare the mercaptosulfide analog 8, the known bromide analog 366b was utilized (Scheme 3). The coupling of 36 with trityl-protected ethane dithiol 3713 using K2CO3 as a base resulted in the Trt-protected mercaptosulfide analog precursor 38. The Trt-deprotection of 38 by treatment with TFA in the presence of triisopropylsilane completed the synthesis of the mercaptosulfide analog 8.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the mercaptosulfide analog 8.

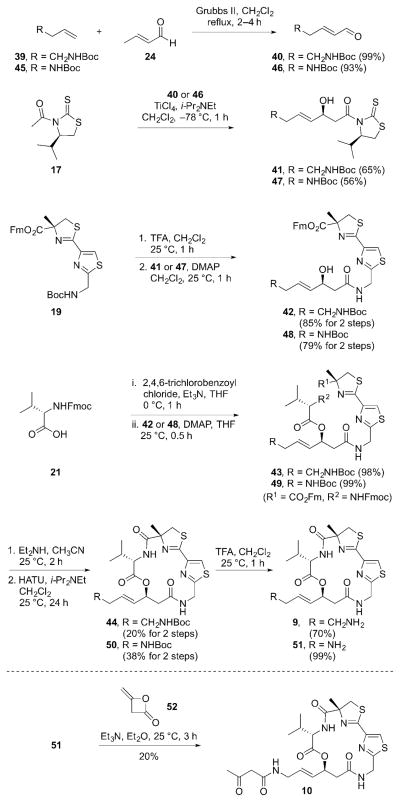

Preparation of the amine analog 9 also utilized the asymmetric-aldol reaction (Scheme 4). The CM reaction of the commercially available 1-(Boc-amino)-3-butene (39) and crotonaldehyde (24) afforded the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 40. The subsequent asymmetric aldol reaction of 40 with 17 resulted in the syn-aldol product 41, which was coupled to 19 to afford the β-hydroxy amide 42. Compound 42 was subjected to Yamaguchi esterification conditions with 21 to give the acyclic precursor 43. The Fm/Fmoc deprotection and HATU-mediated macrolactamization of the resulting amino carboxylic acid gave the Boc-protected intermediate 44. The final Boc-deprotection of 44 by TFA treatment afforded the amine analog 9. For the β-ketoamide analog 10, the penultimate intermediate 51 was prepared in a similar fashion (Scheme 4). The final coupling of 51 with diketene 52 completed the synthesis of 10.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the amine analog 9 and β-ketoamide analog 10.

Biological evaluation of largazole ZBG analogs

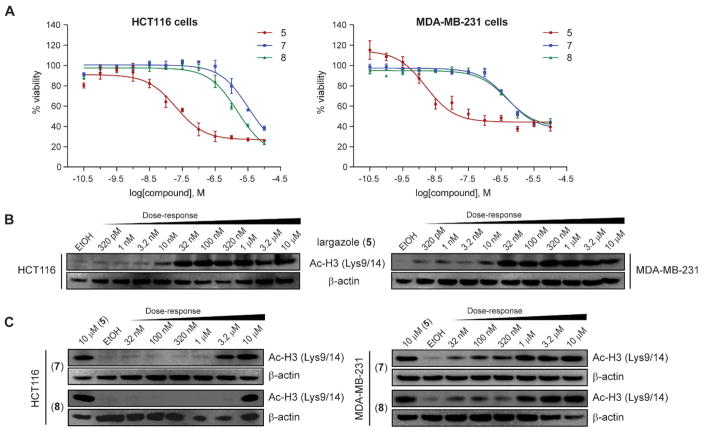

The biological activity of the ZBG analogs was investigated by determining their cytotoxicity against colon cancer (HCT-116) and breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) cell lines (Figure 6A). Compared to largazole (5), which showed very potent cytotoxicity against HCT-116 and MDA-MB-231 cells (IC50 = 20 nM and 1.6 nM, respectively), the two high-affinity ZBG analogs (i.e., hydroxamic acid analog 7 and mercaptosulfide analog 8) displayed significantly reduced activity (IC50 = 3.3 μM and 497 nM for 7; IC50 = 1.5 μM and 480 nM for 8). The medium- and low-affinity ZBG analogs (9–13) did not show any significant activity even at the highest concentration tested (10 μM).

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity and in vitro monitoring of histone hyperacetylation for largazole (5) and high-affinity ZBG analogs (7 and 8). (A) Cell viability of HCT116 and MDA-MB-231 cells was determined after a 48 h-exposure to compound using MTT assay. Histone hyperacetylation in cells was monitored after 8 h-exposure to compound: (B) largazole and (C) analogs 7 and 8; protein lysates were collected and analyzed by immunoblot analysis for histone H3 (Lys9/14) acetylation.

The cytotoxicity effects observed for largazole (5) and high-affinity ZBG analogs (7 and 8) were consistent with the cellular class I HDAC inhibition observed by immunoblot analysis for the hyperacetylation of histone H3 (Lys9/14) (Figure 6B and C). The effects on histone hyperacetylation at 8 h post-treatment showed a dose-dependent increase in both cell lines for all three compounds. We speculate that cell penetration and/or additional targets other than HDACs could be a possible reason for the somewhat greater cytotoxicity observed for 8.

The HDAC isoforms have been divided into 4 different classes of HDACs based on their sequence homology to different yeast transcriptional regulators.14 Along with HDAC1, HDACs 2, 3, and 8 are part of class I HDACs and share sequence homology with RPD3. They are almost exclusively found in the nucleus with the exception of HDAC3, which is found in the cytoplasm as well. Class II HDACs include HDACs 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10 and are related to HDA1. HDACs 6 and 10 are further categorized as class IIb HDACs, due to their unique secondary catalytic domain, even though only HDAC6 possesses a functional secondary catalytic domain. HDAC11, originally classified as a class I HDAC, is a class IV HDAC due to low sequence homology with the other isoforms. The remaining HDACs are class III HDACs, also known as sirtuins for their sequence homology with the yeast transcriptional regulator Sir2. Unlike the 11 “canonical” HDACs, which are zinc-dependent due to the Zn2+ in their active sites, sirtuins are NAD+-dependent and are not inhibited by classical HDAC inhibitors.

The development of single isoform-selective HDAC inhibitors as chemical probes for epigenetic studies has been one of the most active research areas in the field. The selectivity profile of largazole (5)5–6, 6c indicated the class I selectivity of largazole, yet HDACs 1–3 could not be differentiated by largazole, while HDAC8 was inhibited to a much lesser extent. HDAC11, the only class IV member and related to class I isoforms, was also strongly inhibited by largazole (5). Among class II isoforms, only HDAC10 activity was severely compromised in vitro. Largazole (5) had two orders of magnitude lower potency in vitro against HDAC6. Direct comparison with FK228 also indicated that largazole (5) is slightly more active, proving it to be the most potent natural HDAC inhibitor known.5

In order to further evaluate the HDAC inhibition profile of ZBG analogs, their inhibitory activity of in vitro HDAC isoforms was investigated (Table 1). None of the compounds tested, including largazole thiol 6, showed any inhibitory activity against isoforms 4, 7, 9, 11, and sirtuins up to concentrations of 10 μM. Out of the remaining HDAC isoforms, largazole thiol 6 proved to be the most potent HDAC inhibitor, especially against HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 10, displaying sub-nanomolar IC50 values. Once again, the two high-affinity ZBG analogs (7 and 8) were the only ZBG analogs that showed significant activity, while all of the medium- and low-affinity analogs (9–13) failed to show any significant inhibitory activity. The high-affinity ZBG analogs very closely mirrored the activity of largazole thiol 6, albeit at reduced potency. They displayed nanomolar IC50 values for HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 10, and low micromolar activity against HDACs 6 and 8.

Table 1.

HDAC inhibition profile of largazole thiol (6) and ZBG analogs 7–13 (IC50, nM).

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDAC1 | 0.4 | 26 | 40 | NIa | NIa | 30%b | NIa | NIa |

| HDAC2 | 0.9 | 69 | 90 | NIa | NIa | 24%b | NIa | NIa |

| HDAC3 | 0.7 | 29 | 43 | NIa | NIa | 8,000 | NIa | NIa |

| HDAC5 | NIa | 21%b | 22%b | NIa | NIa | NIa | NIa | NIa |

| HDAC6 | 42 | 600 | 2,800 | NIa | 22%b | NIa | 17%b | NIa |

| HDAC8 | 102 | 3,500 | 9,600 | NIa | NIa | NIa | 20%b | 24%b |

| HDAC10 | 0.5 | 21 | 3.6 | NIa | NIa | 49%b | 19%b | NIa |

No significant inhibition (< 15%) at the highest concentration tested (1 μM for 6, 10 μM for other compounds).

Percentage inhibition at 10 μM.

All together, these in vitro assay data showed that the high-affinity ZBG analogs were the only active analogs, while the medium- and low-affinity ZBG analogs lacked any significant activity. This strongly suggests that Zn2+-binding affinity seems to have an effect on both the HDAC inhibition as well as the cytotoxicity of the analogs. However, the significant reduction in potency of the high-affinity ZBG analogs is an interesting phenomenon.

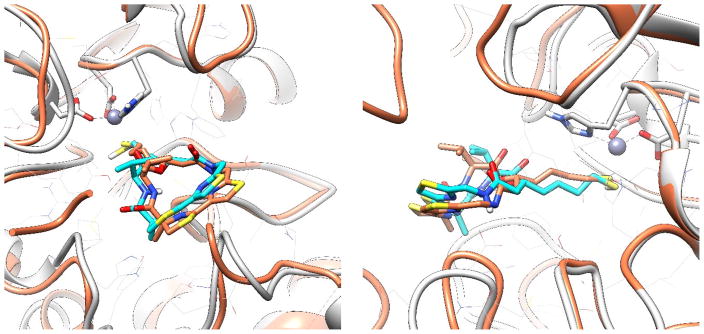

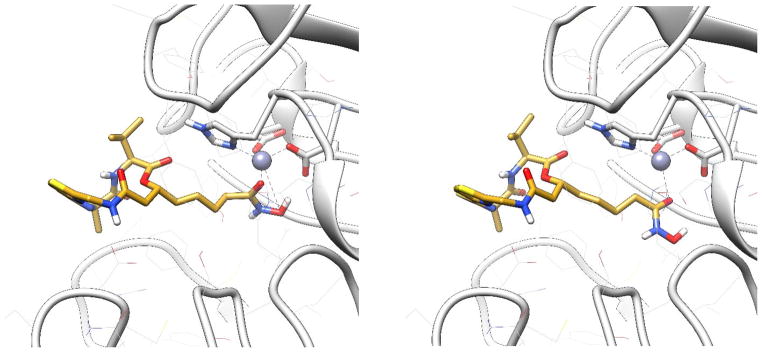

Docking simulations

To explain this phenomenon, we carried out docking simulations. In the binding models generated by AutoDock4, largazole (5) bound to HDAC1 similarly to the way it interacted with HDAC8 (Figure 7). Despite slight deviation of the macrocycle part, the thiol-Zn2+ chelation was almost identical. They both adopted the most favorable tetrahedral zinc coordination. The distance between zinc ion and sulfur atom was around 2.5 Å. However, in all of the docking models generated for analogs 7 and 8, at most only one coordination with zinc ion could be tolerated. For example, in the docking model of 7 (Figure 8), only the carbonyl oxygen atom could have effective coordination (close to 2.0 Å), while the other hydroxy oxygen atom was too far away from metal ion (more than 3.0 Å). A similar situation was observed in the docking mode of 8 (Figure 9). Also, coordination between largazole-thiol and HDAC1-Zn2+ was the most stable among the three compounds. Although the macrocycle fluctuated among those docking models, the thiol group consistently anchored inside the pocket. This coordination was dominant in docking conformational sampling; while the docking model of 7 and 8 showed a more dispersed histogram when clustering binding modes. Analog 8 performed slightly better than analog 7 due to the fact that it also utilizes a second sulfur atom like largazole (5) for coordination. However, the flexibility of the ZBG of 8 (-SCH2CH2SH) increased the steric hindrance during the binding mode searching.

Figure 7.

Top (left) and side (right) views of largazole thiol (6) docking model in HDAC1 active site. Light Gray: HDAC1. Cyan: Largazole thiol (6) docking model. Coral: Crystal structure of largazole thiol (6) co-crystallized with HDAC8 (PDB: 3RQD) superimposed with docking model.

Figure 8.

Two potential binding modes of analog 7 with HDAC1 generated by AutoDock4.

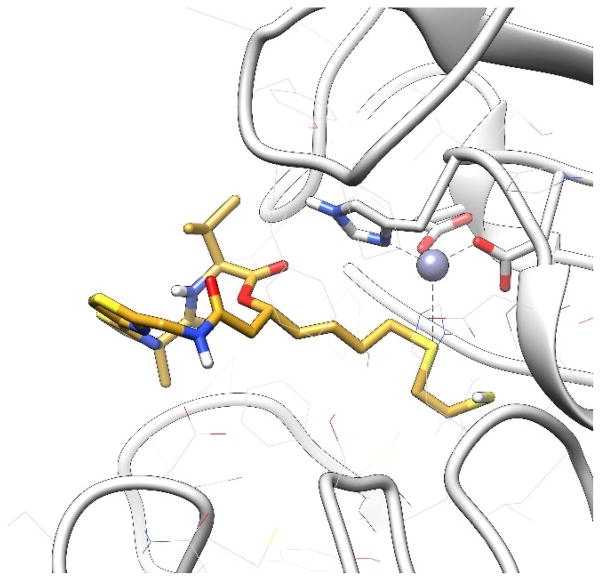

Figure 9.

A potential binding mode of analog 8 with HDAC1 generated by AutoDock4.

Our docking model might explain why largazole (5) showed better inhibitory effect than analogs 7 and 8. It might be because (1) the thiol group is preferred in zinc coordination as the atomic contribution of sulfur atom in binding energy is stronger than carbonyl oxygen atom; (2) the active site seems to be too narrow to accommodate two coordination instead of one from the inhibitors; and (3) more flexible single bonds were introduced in analogs (like analog 8) on aliphatic tail, imposing slightly larger entropic penalty. Based on current docking simulation, it is speculated that a more rigid functional group at the end of tail might increase the chance of constructing stable coordination with zinc ion.

CONCLUSION

HDACs have attracted a great amount of interest due to their implications in cell proliferation and survival. This interest has directly translated into the discovery and development of several HDAC inhibitors as cancer therapeutics. Largazole (5) is a marine natural product and shows an unusual level of differential cytotoxicity via HDAC inhibition. We prepared a series of largazole analogs with various ZBGs to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the ZBGs in HDAC inhibition. While none of the analogs tested were as potent or selective as largazole, the Zn2+-binding affinity of each ZBG correlated with the cytotoxicity and HDAC inhibition of the analogs. The docking simulation study suggested that a more rigid ZBG would increase the chance of achieving steady coordination with zinc ion. We expect that our findings will be an important basis for the future development of new largazole analogs with non-thiol ZBGs for novel therapeutics for cancer.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Procedures

All reactions were conducted in oven-dried glassware under nitrogen. Unless otherwise stated all reagents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, Acros, Chem-Impex, or Fischer and were used without further purification. All solvents were ACS grade or better and used without further purification except tetrahydrofuran (THF) which was freshly distilled from sodium/benzophenone each time before use. Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed with glass backed silica gel (60 Å) plates with fluorescent indication (Whatman). Visualization was accomplished by UV irradiation at 254 nm and/or by staining with p-anisaldehyde solution. Flash column chromatography was performed by using silica gel (particle size 230–400 mesh, 60 Å). All 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded with a Varian 400 (400 MHz) and a Bruker 500 (500 MHz) spectrometer in CDCl3 unless otherwise noted, by using the signal of residual CHCl3, as an internal standard. All NMR δ values are given in ppm, and all J values are in Hz. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry (MS) were recorded with an Agilent 1100 series (LC/MSD trap) spectrometer and were performed to obtain the molecular masses of the compounds. Infrared (IR) absorption spectra were determined with a Thermo-Fisher (Nicolet 6700) spectrometer. Optical rotation values were measured with a Rudolph Research Analytical (A21102. API/1W) polarimeter. The percentage purity of compounds was above 95% as determined by HPLC.

Synthesis of Largazole ZBG Analogs

See the Supporting Information for details.

Cell Viability Assay

Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. HCT116 (1 × 104 per well) and MDA-MB231 (1 × 104 per well) were plated in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. Cells were treated with various concentrations of largazole (5), largazole ZBG analogs (7–13) or vehicle control (1% EtOH) and incubated for 48 h. Cell viability was measured using MTT according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega).

Enzymatic Assays

Enzyme inhibitory assays were carried out by BPS Bioscience. In brief, compounds were incubated with an HDAC enzyme, an appropriate HDAC substrate, bovine serum albumin, and HDAC buffer. Duplicate reactions were carried out at 37 °C for 30 min. The reactions were quenched at the end of the incubation period with the addition of HDAC developer. Reactions were further incubated for 15 min at room temperature prior to fluorescence measurement (ex 360 nm/em 460 nm). The % inhibitory activity was calculated according to the equation (F-Fb)/(Ft-Fb), where F-fluorescent intensity of compound treated wells, Fb-fluorescent intensity of blank wells, Ft-fluorescent intensity of solvent control wells. IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were maintained as above and HCT116 (4 × 105 per well) and MDA-MB-231 (4 × 105 per well) were seeded in 60-mm dishes and incubated overnight. Cells were treated with desired concentrations (0–10 μM final concentration) of largazole (5) and largazole ZBG analogs (7 and 8) and vehicle (1% EtOH) and incubated for 8 h post-treatment. Whole cell lysates were collected in PhosphoSafe buffer (Novagen, Madison, WI), and the protein concentrations were measured using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, probed with antibody and detected with Supersignal Femto Western blotting kit (Pierce). Anti-acetyl histone H3 antibody was purchased from Millipore Corporation (Billerica, MA) and β-actin secondary anti-rabbit antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Docking Simulation

Structure of HDAC1 was taken from crystal structure (PDB: 4BKX). Largazole and analog structures were either taken from crystal structure (PDB: 3RQD) or drawn from scratch and minimized using MM2 module in Chem3D. Molecular dockings were performed by using AutoDock 4.2.15 Gasteiger charges were added onto both receptor and ligand atoms. Grid box was centered at the active site. Dimensions of box was set to 66 × 66 × 66 grid points with spacing of 0.375 Å. Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) was used as a search method. An extended AutoDock force field was used, in which a specialized potential describing the interactions of zinc-coordinating ligands was included.16 All docked conformations were clustered at RMSD of 1.5 Å. All figures were generated by using Chimera.17

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Alvin Crumbliss (Duke) and Dewey McCafferty (Duke) for helpful discussions. This work supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute, R01CA138544, R01CA172310 and R50CA211487) and Debbie and Sylvia DeSantis Professorship (H.L.). We are grateful to the North Carolina Biotechnology Center (North Carolina Biotechnology Center; Grant No. 2008-IDG-1010) for funding of the NMR instrumentation and to the National Science Foundation (NSF) MRI Program (Award ID No. 0923097) for funding mass spectrometry instrumentation.

Footnotes

Notes

HL is a co-founder of Oceanyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc., which is negotiating licenses for largazole-related patents and patent applications.

General experimental procedures including spectroscopic and analytical data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.(a) Handel AE, Ebers GC, Ramagopalan SV. Epigenetics: molecular mechanisms and implications for disease. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arrowsmith CH, Bountra C, Fish PV, Lee K, Schapira M. Epigenetic protein families: a new frontier for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:384–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falkenberg KJ, Johnstone RW. Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:673–691. doi: 10.1038/nrd4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Taori K, Paul VJ, Luesch H. Structure and activity of largazole, a potent antiproliferative agent from the Floridian marine cyanobacterium Symploca sp. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1806–1807. doi: 10.1021/ja7110064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Engene N, Tronholm A, Salvador-Reyes LA, Luesch H, Paul VJ. Caldora penicillata gen. nov., comb. nov. (cyanobacteria), a pantropical marine species with biomedical relevance. J Phycol. 2015;51:670–681. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Salvador-Reyes LA, Engene N, Paul VJ, Luesch H. Targeted natural products discovery from marine cyanobacteria using combined phylogenetic and mass spectrometric evaluation. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:486–492. doi: 10.1021/np500931q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Salvador LA, Byeon S, Ying Y, Kwan JC, Law BK, Hong J, Luesch H. Anticolon cancer activity of largazole, a marine-derived tunable histone deacetylase inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:351–361. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong J, Luesch H. Largazole: from discovery to broad-spectrum therapy. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:449–456. doi: 10.1039/c2np00066k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Ying Y, Taori K, Kim H, Hong J, Luesch H. Total synthesis and molecular target of largazole, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8455–8459. doi: 10.1021/ja8013727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Seiser T, Kamena F, Cramer N. Synthesis and biological activity of largazole and derivatives. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:6483–6485. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bowers A, West N, Taunton J, Schreiber SL, Bradner JE, Williams RM. Total synthesis and biological mode of action of largazole: a potent class I histone deacetylase inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11219–11222. doi: 10.1021/ja8033763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ren Q, Dai L, Zhang H, Tan W, Xu Z, Ye T. Total synthesis of largazole. Synlett. 2008;15:2379–2383. [Google Scholar]; (e) Numajiri Y, Takahashi T, Takagi M, Shin-Ya K, Doi T. Total synthesis of largazole and its biological evaluation. Synlett. 2008;16:2483–2486. [Google Scholar]; (f) Nasveschuk CG, Ungermannova D, Liu X, Phillips AJ. A concise total synthesis of largazole, solution structure, and some preliminary structure activity relationships. Org Lett. 2008;10:3595–3598. doi: 10.1021/ol8013478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Ghosh AK, Kulkarni S. Enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-largazole, a potent inhibitor of histone deacetylase. Org Lett. 2008;10:3907–3909. doi: 10.1021/ol8014623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Wang B, Forsyth CJ. Total synthesis of largazole - devolution of a novel synthetic strategy. Synthesis. 2009;17:2873–2880. [Google Scholar]; (i) Zeng X, Yin B, Hu Z, Liao C, Liu J, Li S, Li Z, Nicklaus MC, Zhou G, Jiang S. Total synthesis and biological evaluation of largazole and derivatives with promising selectivity for cancers cells. Org Lett. 2010;12:1368–1371. doi: 10.1021/ol100308a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Souto JA, Vaz E, Lepore I, Pöppler AC, Franci G, Álvarez R, Altucci L, de Lera ÁR. Synthesis and biological characterization of the histone deacetylase inhibitor largazole and C7-modified analogues. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4654–4667. doi: 10.1021/jm100244y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Xiao Q, Wang LP, Jiao XZ, Liu XY, Wu Q, Xie P. Concise total synthesis of largazole. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2010;12:940–949. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2010.510114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Benelkebir H, Marie S, Hayden AL, Lyle J, Loadman PM, Crabb SJ, Packham G, Ganesan A. Total synthesis of largazole and analogues: HDAC inhibition, antiproliferative activity and metabolic stability. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:3650–3658. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Bhansali P, Hanigan CL, Casero RA, Jr, Tillekeratne LMV. Largazole and analogues with modified metal-binding motifs targeting histone deacetylases: synthesis and biological evaluation. J Med Chem. 2011;54:7453–7463. doi: 10.1021/jm200432a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Morris JC, Phillips AJ. Marine natural products: synthetic aspects. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1186–1203. doi: 10.1039/b919366a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Newkirk TL, Bowers AA, Williams RM. Discovery, biological activity, synthesis and potential therapeutic utility of naturally occurring histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:1293–1320. doi: 10.1039/b817886k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole KE, Dowling DP, Boone MA, Phillips AJ, Christianson DW. Structural basis of the antiproliferative activity of largazole, a depsipeptide inhibitor of the histone deacetylases. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12474–12477. doi: 10.1021/ja205972n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Kim B, Hong J. An overview of naturally occurring histone deacetylase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2014;14:2759–2782. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666141208105614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ying Y, Liu Y, Byeon SR, Kim H, Luesch H, Hong J. Synthesis and activity of largazole analogues with linker and macrocycle modification. Org Lett. 2008;10:4021–4024. doi: 10.1021/ol801532s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bhansali P, Hanigan CL, Perera L, Casero RA, Jr, Tillekeratne LMV. Synthesis and biological evaluation of largazole analogues with modified surface recognition cap groups. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;86:528–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang B, Huang PH, Chen CS, Forsyth CJ. Total syntheses of the histone deacetylase inhibitors largazole and 2-epilargazole: application of N-heterocyclic carbene mediated acylations in complex molecule synthesis. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1140–1150. doi: 10.1021/jo102478x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bowers AA, West N, Newkirk TL, Troutman-Youngman AE, Schreiber SL, Wiest O, Bradner JE, Williams RM. Synthesis and histone deacetylase inhibitory activity of largazole analogs: alteration of the zinc-binding domain and macrocyclic scaffold. Org Lett. 2009;11:1301–1304. doi: 10.1021/ol900078k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chen F, Gao AH, Li J, Nan FJ. Synthesis and biological evaluation of C7-demethyl largazole analogues. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1269–1272. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Li X, Tu Z, Li H, Liu C, Li Z, Sun Q, Yao Y, Liu J, Jiang S. Biological evaluation of new largazole analogues: alteration of macrocyclic scaffold with click chemistry. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:132–136. doi: 10.1021/ml300371t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Guerra-Bubb JM, Bowers AA, Smith WB, Paranal R, Estiu G, Wiest O, Bradner JE, Williams RM. Synthesis and HDAC inhibitory activity of isosteric thiazoline-oxazole largazole analogs. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:6025–6028. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Salvador LA, Park H, Al-Awadhi FH, Liu Y, Kim B, Zeller SL, Chen QY, Hong J, Luesch H. Modulation of activity profiles for largazole-based HDAC inhibitors through alteration of prodrug properties. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2014;5:905–910. doi: 10.1021/ml500170r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Kim B, Park H, Salvador LA, Serrano PE, Kwan JC, Zeller SL, Chen QY, Ryu S, Liu Y, Byeon S, Luesch H, Hong J. Evaluation of class I HDAC isoform selectivity of largazole analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:3728–3731. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Su J, Qiu Y, Ma K, Yao Y, Wang Z, Li X, Zhang D, Tu Z, Jiang S. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of largazole derivatives: alteration of the zinc-binding domain. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:7763–7769. [Google Scholar]; (l) Schotes C, Ostrovskyi D, Senger J, Schmidtkunz K, Jung M, Breit B. Total synthesis of (18S) - and (18R)-homolargazole by rhodium-catalyzed hydrocarboxylation. Chem - Eur J. 2014;20:2164–2168. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Clausen DJ, Smith WB, Haines BE, Wiest O, Bradner JE, Williams RM. Modular synthesis and biological activity of pyridyl-based analogs of the potent class I histone deacetylase inhibitor largazole. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:5061–5074. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Almaliti J, Al-Hamashi AA, Negmeldin AT, Hanigan CL, Perera L, Pflum MKH, Casero RA, Jr, Tillekeratne LMV. Largazole analogues embodying radical changes in the depsipeptide ring: development of a more selective and highly potent analogue. J Med Chem. 2016;59:10642–10660. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith RM, Martell AE. Critical stability constants, enthalpies and entropies for the formation of metal complexes of aminopolycarboxylic acids and carboxylic acids. Sci Total Environ. 1987;64:125–147. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen JA, Jourden JLM, Miller MT, Cohen SM. To bind zinc or not to bind zinc: an examination of innovative approaches to improved metalloproteinase inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta, Mol Cell Res. 2010;1803:72–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gribkov DV, Hultzsch KC, Hampel F. 3,3′-Bis(trisarylsilyl)-substituted binaphtholate rare earth metal catalysts for asymmetric hydroamination. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3748–3759. doi: 10.1021/ja058287t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson WH, Check CT, Proust N, Stambuli JP. Allylic oxidations of terminal olefins using a palladium thioether catalyst. Org Lett. 2010;12:824–827. doi: 10.1021/ol902905w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermes JP, Sander F, Peterle T, Urbani R, Pfohl T, Thompson D, Mayor M. Gold nanoparticles stabilized by thioether dendrimers. Chem - Eur J. 2011;17:13473–13481. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Ruijter AJM, Van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, Van Kuilenburg ABP. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J. 2003;370:737–749. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huey R, Morris GM, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. A semiempirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation. J Comput Chem. 2007;28:1145–1152. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos-Martins D, Forli S, Ramos MJ, Olson AJ. AutoDock4Zn: an improved AutoDock force field for small-molecule docking to zinc metalloproteins. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54:2371–2379. doi: 10.1021/ci500209e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comp Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.