Hyperoxia is used to measure the distribution of ventilation in imaging and MBW but may alter the underlying ventilation distribution. We used MBW to evaluate the effect of inspired oxygen concentration on the ventilation distribution using 10% argon as a tracer. Short-duration exposure to hypoxia (12.5% oxygen) and hyperoxia (90% oxygen) during MBW had no significant effect on ventilation heterogeneity, suggesting that hyperoxia can be used to assess the ventilation distribution.

Keywords: hyperoxia, multiple breath washout, oxygen enhanced imaging, ventilation heterogeneity

Abstract

Multiple breath washout (MBW) and oxygen-enhanced MRI techniques use acute exposure to 100% oxygen to measure ventilation heterogeneity. Implicit is the assumption that breathing 100% oxygen does not induce changes in ventilation heterogeneity; however, this is untested. We hypothesized that ventilation heterogeneity decreases with increasing inspired oxygen concentration in healthy subjects. We performed MBW in 8 healthy subjects (4 women, 4 men; age = 43 ± 15 yr) with normal pulmonary function (FEV1 = 98 ± 6% predicted) using 10% argon as a tracer gas and oxygen concentrations of 12.5%, 21%, or 90%. MBW was performed in accordance with ERS-ATS guidelines. Subjects initially inspired air followed by a wash-in of test gas. Tests were performed in balanced order in triplicate. Gas concentrations were measured at the mouth, and argon signals rescaled to mimic a N2 washout, and analyzed to determine the distribution of specific ventilation (SV). Heterogeneity was characterized by the width of a log-Gaussian fit of the SV distribution and from Sacin and Scond indexes derived from the phase III slope. There were no significant differences in the ventilation heterogeneity due to altered inspired oxygen: histogram width (hypoxia 0.57 ± 0.11, normoxia 0.60 ± 0.08, hyperoxia 0.59 ± 0.09, P = 0.51), Scond (hypoxia 0.014 ± 0.011, normoxia 0.012 ± 0.015, hyperoxia 0.010 ± 0.011, P = 0.34), or Sacin (hypoxia 0.11 ± 0.04, normoxia 0.10 ± 0.03, hyperoxia 0.12 ± 0.03, P = 0.23). Functional residual capacity was increased in hypoxia (P = 0.04) and dead space increased in hyperoxia (P = 0.0001) compared with the other conditions. The acute use of 100% oxygen in MBW or MRI is unlikely to affect ventilation heterogeneity.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Hyperoxia is used to measure the distribution of ventilation in imaging and MBW but may alter the underlying ventilation distribution. We used MBW to evaluate the effect of inspired oxygen concentration on the ventilation distribution using 10% argon as a tracer. Short-duration exposure to hypoxia (12.5% oxygen) and hyperoxia (90% oxygen) during MBW had no significant effect on ventilation heterogeneity, suggesting that hyperoxia can be used to assess the ventilation distribution.

breathing 100% oxygen is commonly used in pulmonary physiology, where it is used to noninvasively obtain information about the spatial distribution of ventilation. For example, the most commonly used method for performing multiple breath washout (MBW) relies on the pattern of nitrogen elimination when a subject is rapidly switched from breathing room air to 100% oxygen. By examining the quasi-exponential washout the underlying distribution of specific ventilation can be inferred (38). By monitoring the slope of the change in expired nitrogen on a breath-by-breath basis as the subject breathes 20–30 breaths after the switch, information can be gained about the global uniformity and/or spatial distribution in the acinar regions as well as the conducting airways of the lung (3, 4, 13, 45, 57). In addition, recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques have exploited the ability of oxygen to alter the underlying magnetic resonance properties of tissue. These use 100% oxygen, which is paramagnetic, as a contrast agent to map the spatial distribution of ventilation. This is done by having the subject breathe 20 breaths of 100% oxygen alternating with 20 breaths of room air and measuring the regional change in the magnetic resonance signal intensity (46, 47). Regions of the lung that have high specific ventilation show a rapid change in signal intensity whereas regions of the lung that are poorly ventilated (low specific ventilation) show a delayed response. From the time course of the response, essentially a spatially resolved MBW, both a histogram of the distribution and a map of regional specific ventilation, can be constructed (46, 47). When specific ventilation imaging is combined with measures of proton density, regional alveolar ventilation can be calculated (32).

Implicit in the use of 100% oxygen to measure ventilation heterogeneity is the assumption that breathing 100% oxygen does not change the underlying physiology and consequently the heterogeneity or distribution of ventilation. However, this is unproven. Possible mechanisms by which hyperoxia could affect the ventilation heterogeneity include by acting directly on the airways or indirectly by affecting hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and the underlying ventilation-perfusion ratio. The effects of altered inspired oxygen on the airways is poorly understood, but some studies report that hypoxia results in bronchoconstriction and decreases in collateral ventilation (41, 54); hyperoxia may also have small effects acting to increase airway caliber and alter lung mechanics (29). Further, hyperoxia has the potential to affect the local ventilation-perfusion ratio by releasing hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (17, 18, 40). This would be expected to decrease the V̇a/Q̇ ratio in lung units where HPV was previously active, with a corresponding reduction in oxygen uptake, and a decrease in the expired nitrogen from these lung units. This effect, if present, would result in an apparent increase in measured ventilation heterogeneity with hyperoxia; conversely hypoxia would be expected to decrease ventilation heterogeneity. In addition, the effects of altering HPV on the local V̇a/Q̇ ratio may also alter local CO2 with associated effects on local lung mechanics and ventilation (22, 23).

Although for multiple breath washout the typical inspired gas is 100% oxygen, and the elimination of nitrogen is monitored, other inert gases, such as the wash-in of 10% argon, can be used equally well to measure the distribution and heterogeneity of ventilation (30, 31). The advantage of using argon as the tracer is that the inspired oxygen concentration can be independently altered, allowing the effects of oxygen on the distribution of ventilation to be assessed. We hypothesized that the heterogeneity of ventilation is decreased with increasing inspired oxygen concentration, consistent with a predominant effect of oxygen acting on airway smooth muscle as a bronchodilator. We tested this using multiple breath washin with 10% argon as the marker gas under normoxic (21% oxygen), hypoxic (12.5% oxygen), and hyperoxic (90% oxygen) conditions. Below and throughout the manuscript we refer to the measurement of the wash-in of argon in this fashion as a washout because the argon signal is inverted and normalized, and then analyzed in exactly the same manner as a nitrogen washout.

METHODS

This study was approved by the University of California, San Diego's Human Subjects Research Protection Program. Subjects participated after giving written, informed consent.

Overview of Study Design

Potential subjects underwent screening for exclusion criteria that included history of cardiopulmonary disease. All subjects were studied on one occasion with baseline pulmonary function testing with spirometry and multiple breath washout (argon wash-in) tests in the seated position. The order for presenting the altered oxygen concentration test gases was balanced between subjects. Data at each inspired oxygen concentration were obtained in triplicate and the results averaged. Oxygen saturation and heart rate were monitored using pulse oximetry.

Multiple Breath Washout (MBW)

Experimental setup.

To quantify whole lung ventilation heterogeneity, multiple breath washout (argon wash-in) was performed in accordance with the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society (ERS-ATS) guidelines (44) as previously described (20, 42, 56) using a non-rebreathing bag-in-box system with separate bags for inspired and expired gases. This protocol was followed aside from modifications allowing the inspired oxygen concentration to be altered. This was done by creating a multiple breath “nitrogen” washout curve from the wash-in of argon, an inert nonresident gas, as described previously (43). In normoxia the test gas was Ar 10%, O2 21%, N2 69% whereas in hypoxia the test gas was Ar 10%, O2 12.5%, N2 78% and in hyperoxia Ar 10%, O2 90%, N2 0%.

Flow was measured with a pneumotachograph (Fleish no. 2), located in the wall of the bag-in-box system and gas concentrations measured with rapid-responding mass-spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer MGA 1100, Pomona, CA) sampling near the mouth. Gas concentrations were acquired at 200 Hz using an analog-to-digital converter and dedicated computer software. Flow was calibrated using a 3-liter syringe (Hans-Rudolph) at a target flow rate of 0.5 l/s for each subject.

Protocol.

The subject sat upright wearing a nose clip while breathing air through a mouthpiece connected to the bag-in-box circuit with a non-rebreathing valve. Subjects were instructed to target a flow rate of 0.5 l/s and an inspiratory and expiratory time of 2 s each using a metronome and a flowmeter. Once the subject achieved a stable breathing pattern, the inspired gas was switched to the test gas mixture (10% Ar, and 12.5, 21, or 90% O2, balance N2). Data were acquired until the exhaled concentration of argon was within 2% of the inhaled concentration (end-tidal argon concentration ≥ 9.8%). The inhaled gas mixture was then switched back to room air and the test terminated. Once the measured end-tidal argon concentration was <1%, reflecting the concentration of the room air gas mixture, the test was repeated. Tests were performed in triplicate for each oxygen condition, with total test time per subject of ~60 min.

Data analysis.

Data were first corrected for mass spectrometer transit time determined as the time between a measured flow signal and the mass spectrometer reaching 50% concentration following a sharp puff of CO2. This transit delay time was ~600 ms, and includes the lag time and also the dynamic response time of the mass spectrometer (7). The flow was converted to body temperature and pressure saturated (BTPS) conditions and the argon concentration normalized to appear as if it were resident gas washout (nitrogen) as described (43). This normalization and inversion of the argon signal allowed the use of existing software that has been extensively evaluated for objective analysis of washout data (51). Normalization assumed the pretest concentration of resident gas in the lung was 78% and rescaled the signal to cover the range of 78% to 0% inspired concentration. The mixed expired gas concentration was determined from the integration of the product of flow and instantaneous gas concentration of the end-tidal gas concentrations. The cumulative expired gas volume over the course of the “washout” was determined.

Mean expired concentration was computed from flow and the normalized gas signal and used to determine the distribution of specific ventilation using the method described by Lewis et al. (38). Fifty compartments uniformly spaced in log scale spanning the range of specific ventilation from 0.01 to 10 were used in the analysis. From this, the most likely distribution of specific ventilation within the lungs was computed from a fit to the histogram using constrained least-squares regression. Heterogeneity was expressed as the full width half max of the recovered distribution (width).

Dedicated computer software for automated analysis of the washout curve (generated from the inverted normalized argon wash-in) as previously described (51) was used to generate indexes Sacin, and Scond based on the phase III slope. FRC was calculated from the volume of “nitrogen” (i.e., inverted and rescaled argon) washed in assuming the distribution of gas was uniform at the onset of the test and also at the end. FRC was determined from mass balance (57) as the net volume of cumulative expired gas (in this case the inverted and rescaled argon “nitrogen” concentration) down to the point where expired gas falls below 1/40 of initial concentration divided by the difference between the initial and final concentrations of the gas. The net volume of gas expired was calculated from the flow weighted sum of the integral of flow and gas concentration breath corrected for dead space.

Lung clearance index was defined as the number of turnovers [measured cumulative expired volume divided by functional residual capacity (FRC)] required to reduce expired concentration to 2% of the inspired level. Curvilinearity was computed as one minus the ratio of two regression slopes obtained from the semilog plot of mean expired “apparent” N2 concentration (i.e., rescaled Ar) vs. turnover. The regression slopes of the ratio were determined from the range of turnover = 0 and turnover = LCI/2 for the denominator and turnover = LCI/2 and turnover = LCI for the numerator.

Bohr and Fowler dead spaces were calculated. as previously described (13, 26). Bohr dead space was defined for each breath as the exhaled volume multiplied by the difference between end-tidal and mean expired gas concentration normalized by end-tidal expired gas concentration. Fowler dead space was calculated as the midvolume of phase II resulting in equal areas under and above the curve as defined by Fowler (26). Bohr and Fowler dead spaces were calculated for the first five breaths of each test and averaged.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SD. ANOVA for repeated measures designs was used to evaluate the difference between normoxia and hypoxia and hyperoxia for all indexes derived from the washout analysis. Where overall significance occurred, post hoc testing was conducted using Student’s t-test. Statistical analyses were performed using Statview (Statview 4.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Significance was accepted at P < 0.05, 2 tailed.

RESULTS

Subjects

A total of 8 subjects between 20 and 58 yr old (mean = 43 ± 15 yr) were enrolled and participated in the study. No subject had a history of cardiopulmonary disease, and spirometry was normal in all cases. All of the subjects tolerated the study well. Subject descriptive data are provided in Table 1. Heart rate and oxygen saturation data are given in Table 2. Breathing the 20–30 breaths of hypoxia gas for the hypoxic test resulted in a significant increase in heart rate (P = 0.02) and a significant decrease in oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximeter from 98.1 ± 0.05% in normoxia to 93.1 ± 3.2% in hypoxia (P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and pulmonary function data

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 43 ± 15 |

| Height, cm | 172 ± 10 |

| Weight, kg | 76.3 ± 20.5 |

| FVC, liters | 4.36 ± 0.59 |

| FVC pred, % | 100 ± 9 |

| FEV1, liters | 3.48 ± 0.79 |

| FEV1 pred, % | 98 ± 6 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.80 ± 0.08 |

| FEV1/FVC pred, % | 99 ± 10 |

Data are means ± SD; n = 8. FVC, forced vital capacity; FVC pred, forced vital capacity, percent of predicted; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FEV1pred, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, percent of predicted; FEV1/FVC, forced vital capacity/forced expiratory volume in 1 s, ratio; FEV1/FVC pred, forced vital capacity/forced expiratory volume in 1 s, ratio, percent of predicted.

Table 2.

Oxygen saturation and heart rate during multiple breath washouts at different inspired oxygen concentrations

| Condition | Hypoxia | Normoxia | Hyperoxia | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2, % | 12.5 | 21 | 90 | |

| SpO2, % | 93.1 ± 3.2* | 98.1 ± 0.6 | 98.6 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| HR, beats/min | 70.1 ± 4.6* | 66.7 ± 4.0 | 65.3 ± 4.7 | 0.02 |

Data are means ± SD; n = 8. SpO2, oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry; HR, heart rate.

Significantly different, P < 0.05, compared with normoxia and hyperoxia on post hoc testing.

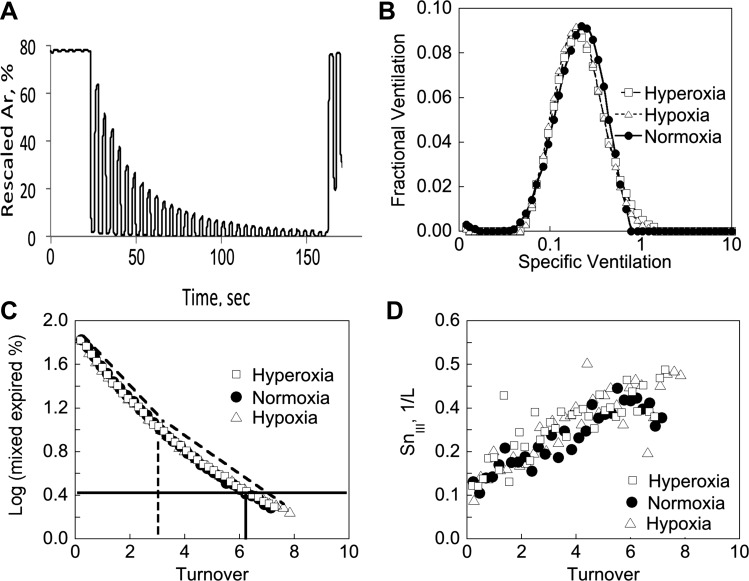

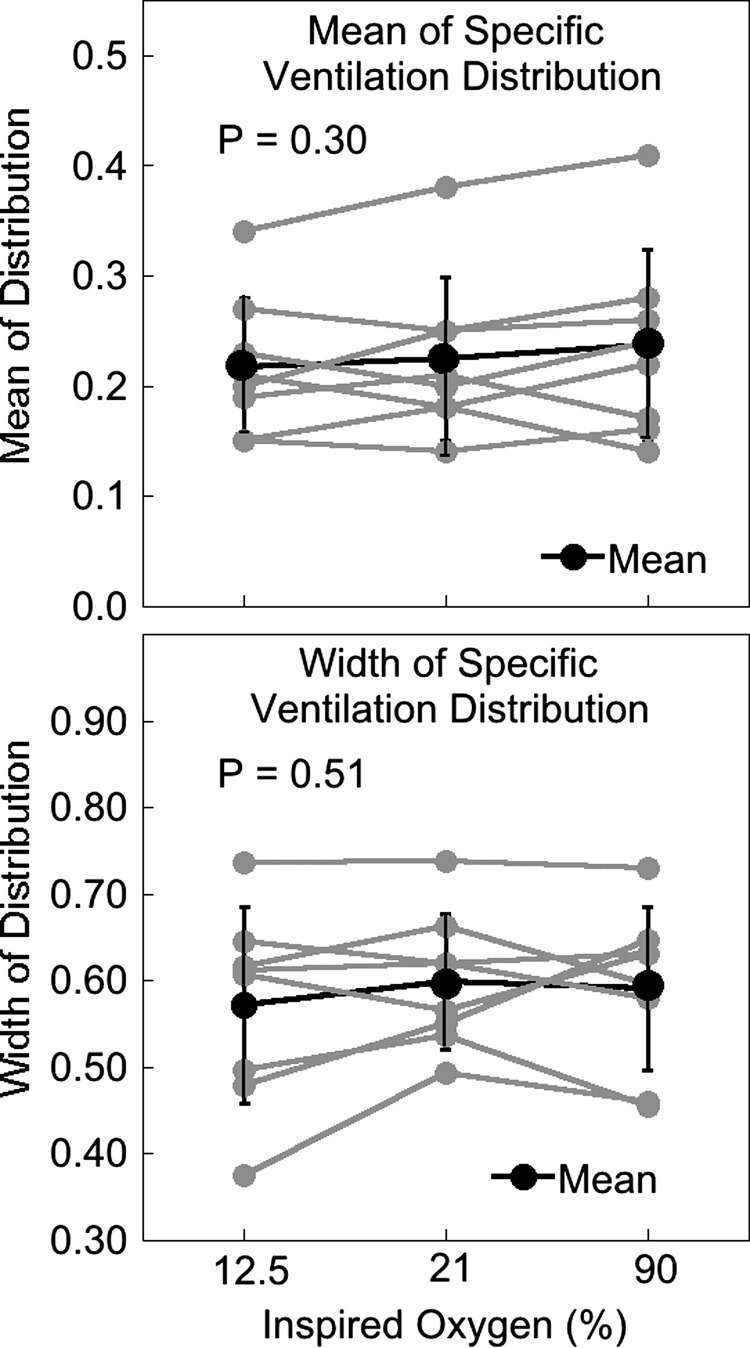

Multiple Breath “Washout”

There was no difference in measured tidal volume across conditions (P = 0.16). Table 3 summarizes the derived MBW indexes for each O2 condition. An example inverted and normalized argon “washout” tracing in normoxia and data analyses across the three different inspired oxygen conditions are shown for one subject (subject MBW1) in Fig. 1. Across all subjects, there was no significant change in the histogram mean (hypoxia 0.22 ± 0.06, normoxia 0.22 ± 0.07, hyperoxia 0.24 ± 0.09, P = 0.30), width (hypoxia 0.57 ± 0.11, normoxia 0.60 ± 0.08, hyperoxia 0.59 ± 0.09, P = 0.51), or R2 (P = 0.44) with inspired oxygen concentrations. Individual subject data are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

MBW metrics for all subjects

| Condition | Hypoxia | Normoxia | Hyperoxia | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2, % | 12.5 | 21 | 90 | |

| Histogram mean | 0.22 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.24 ± 0.09 | 0.30 |

| Histogram width | 0.57 ± 0.11 | 0.60 ± 0.08 | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 0.51 |

| R2 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 0.44 |

| LCI | 6.61 ± 0.39 | 6.50 ± 0.31 | 6.66 ± 0.26 | 0.23 |

| Curvilinearity | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Scond | 0.014 ± 0.011 | 0.012 ± 0.015 | 0.010 ± 0.011 | 0.34 |

| Sacin | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.23 |

| VI, ml | 1,137 ± 51 | 1,105 ± 74 | 1,137 ± 79 | 0.16 |

| FRC, ml | 4,206 ± 715* | 3,973 ± 764 | 3,840 ± 759 | 0.04 |

| Fowler dead space, ml | 170 ± 38† | 169 ± 45† | 202 ± 46 | 0.0001 |

| Bohr dead space, ml | 192 ± 35† | 189 ± 33† | 233 ± 37 | <0.0001 |

Data are means ± SD; n = 8. R2, fit of the histogram distribution; LCI, lung clearance index; VI inspired tidal volume; FRC, functional residual capacity measured during MBW. Significantly different from hyperoxia:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.0001 on post hoc testing.

Fig. 1.

A: example tracing of the wash-in of argon in normoxia from one subject, MBW1. Argon signal is inverted and rescaled to mimic a nitrogen washout as described in Ref. 43. Data shown in B, C, and D are for one subject (subject MBW1) measured with O2 = 12.5% (hypoxia), 21% (normoxia), and 90% (hyperoxia). B: example plots of the specific ventilation distribution in each O2 concentration showing the fit to the 50-compartment model as described in Ref. 38. C: the plot of log mixed expired gas concentration (rescaled argon) against turnover (cumulative expired volume/FRC) from subject MBW1 is used to calculate lung clearance index (LCI) and curvilinearity. The horizontal solid line shows the point where “N2” concentration is reduced to 2% of the inspired level in the normoxic plot, and the vertical solid line the associated LCI for this O2 concentration. For curvilinearity the LCI/2 is determined, shown by the vertical dashed line, and then two regression slopes (shown as dashed lines just above the plotted points) between the range turnover = 0 and turnover = LCI/2 (vertical dashed line) and turnover = LCI/2 and turnover = LCI determined. Curvilinearity calculated as one minus the ratio of the two slopes. D: the plot of the phase III slope vs turnover. Scond is calculated as the regression slope between turnovers 1.5 and 6. Sacin is determined as the value of the 1st breath minus the slope (i.e., Scond), which accounts for the small contribution of the rate of rise due to convective inhomogeneities.

Fig. 2.

Top: mean of the recovered specific ventilation distribution in hypoxia, normoxia, and hyperoxia for each subject (n = 8). Bottom: width of the recovered specific ventilation distribution in hypoxia, normoxia, and hyperoxia for each subject. There are no significant changes in either mean or width of the distribution with different oxygen concentrations.

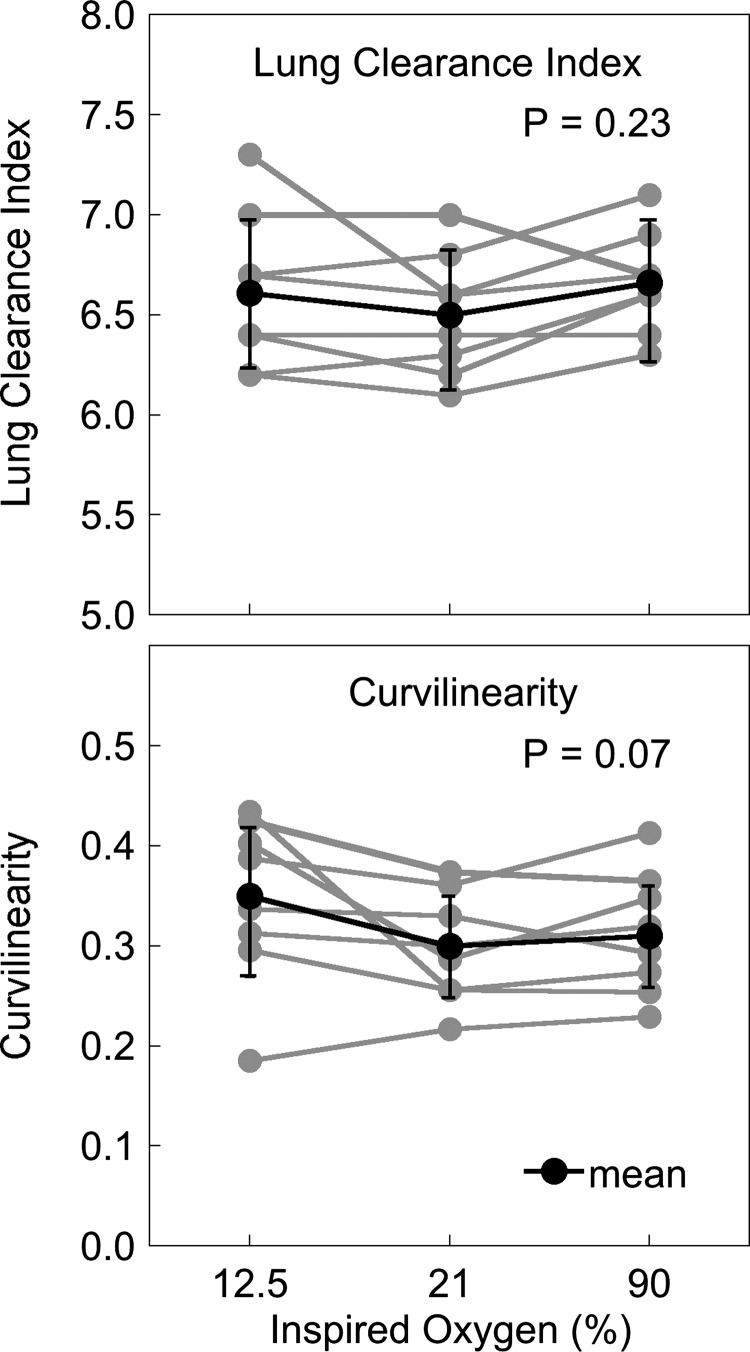

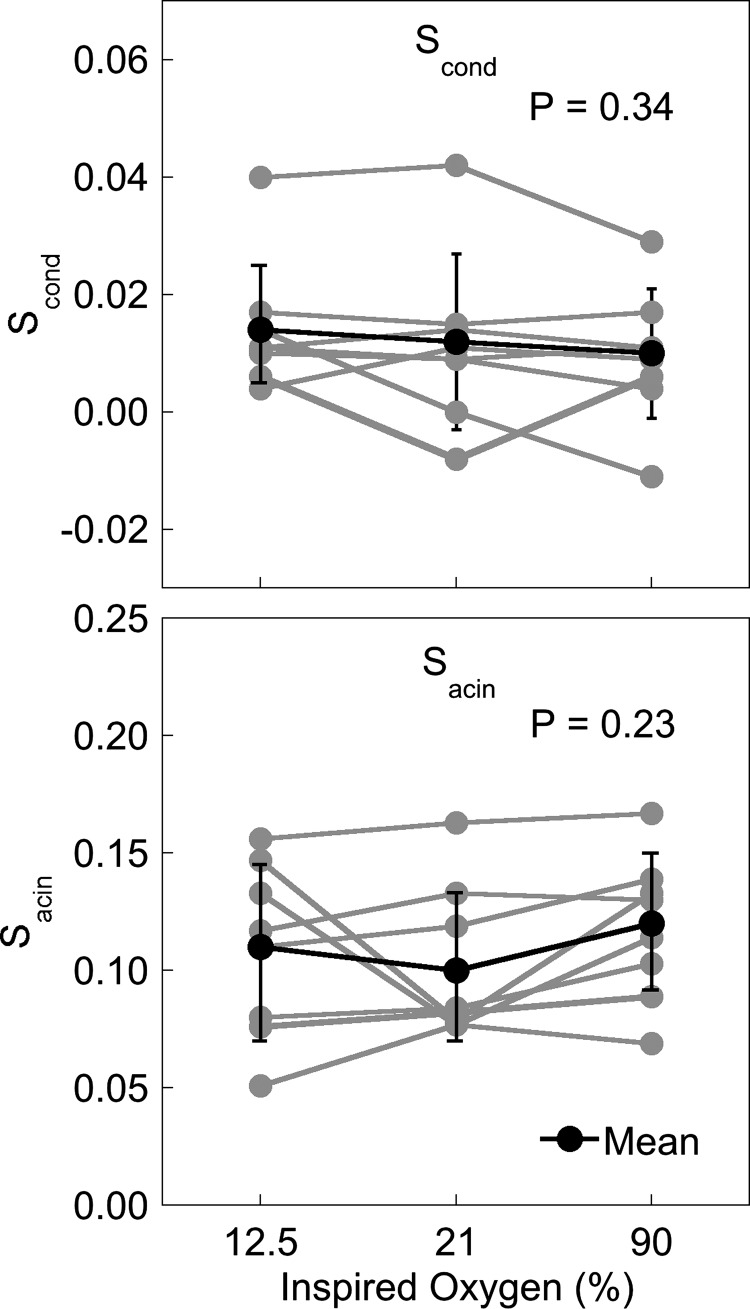

Individual subject data for lung clearance index and curvilinearity are given in Fig. 3. Lung clearance index did not change significantly between the different oxygen conditions (hypoxia 6.61 ± 0.39, normoxia 6.50 ± 0.31, hyperoxia 6.66 ± 0.26, P = 0.23). There was a tendency for the curvilinearity of the MBW washout to be greater in hypoxia, but this was not statistically significant (hypoxia 0.35 ± 0.08, normoxia 0.30 ± 0.05, hyperoxia 0.31 ± 0.06, P = 0.07). The index of conducting airway heterogeneity, Scond, (Fig. 4, top) was not significantly different across inspired oxygen conditions (P = 0.34). Similarly, Sacin (Fig. 4, bottom) was also not significantly different in hypoxia or hyperoxia compared with the normoxic condition (P = 0.23).

Fig. 3.

Lung clearance index (LCI) (top) and curvilinearity (bottom) in hypoxia, normoxia, and hyperoxia for each subject (n = 8). There are no significant changes in either LCI or curvilinearity with different oxygen concentrations.

Fig. 4.

Scond (top) and Sacin (bottom) in hypoxia, normoxia, and hyperoxia for each subject (n = 8). There are no significant changes in either Scond or Sacin with different oxygen concentrations.

To evaluate the cumulative effects of multiple wash-in and washout of altered oxygen concentrations, the three repeat measures of histogram width, Scond, and Sacin were compared and are shown in Table 4. There was no significant time-dependent effect of hypoxia (P = 0.37) or hyperoxia (P = 0.11) on the width of the histogram. There was also no significant time-dependent effect of hypoxia for Scond (P = 0.81) or Sacin (P = 0.23) across the three repeated measurements (Table 4). Similarly, there was no significant change in hyperoxia on Scond (P = 0.11) or Sacin (P = 0.84) across the three measurements.

Table 4.

Effect of repeated exposure to hypoxia and hyperoxia on the specific ventilation (SV) histogram width, Scond, and Sacin

| Hypoxia (12.5% O2) |

Hyperoxia (90% O2) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure: | 1 | 2 | 3 | P | 1 | 2 | 3 | P |

| SV histogram width | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Scond | 0.016 ± 0.012 | 0.014 ± 0.015 | 0.014 ± 0.010 | 0.81 | 0.005 ± 0.018 | 0.015 ± 0.008 | 0.009 ± 0.012 | 0.11 |

| Sacin | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.84 |

Data are means ± SD; n = 8. There is no significant time-dependent effect in either hypoxia or hyperoxia.

FRC was significantly different between conditions (hypoxia 4,206 ± 715 ml, normoxia 3,973 ± 764 ml, hyperoxia 3,840 ± 759 ml) with the difference between hypoxia and hyperoxia reaching significance on post hoc testing (P = 0.01). Both Bohr and Fowler dead spaces were significantly increased in hyperoxia (both P < 0.0001) compared with normoxia and hypoxia (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Since the introduction of the analysis of nitrogen washout following a single breath of oxygen by Fowler, Comroe and Kety (12, 24, 25), which was later modified to analyze the effect of several breaths (16, 27), the use of 100% oxygen to study the distribution of ventilation and associated heterogeneity has been a mainstay of pulmonary physiology for decades. Despite this, little is known about potential confounding effects of inspiration of 100% oxygen on regional ventilation. In contrast to the well-documented changes in the pulmonary vasculature, much less is known about the responsiveness of the airways to stimuli that could potentially alter local ventilation. Airway smooth muscle is distributed from the upper airway to the start of the terminal bronchioles and beyond to at least the start of respiratory bronchioles (21, 37) (about generation 16). Thus factors affecting smooth muscle tone have the potential to influence the distribution of ventilation by affecting airway diameter proximal to the gas exchanging regions of the lung. There is evidence, as discussed below, that airway smooth muscle tone is affected by both oxygen and carbon dioxide and thus this raises the possibility that the underlying physiology could be altered by hyperoxia, changing the ventilation distribution and measures of heterogeneity. Our data suggest that this is unlikely to be a factor in healthy subjects during the short-term exposure to hyperoxia such as during MBW measurements or during oxygen-enhanced ventilation imaging techniques such as with specific ventilation imaging.

Altered Respiratory Gases, Airways, and the Measurement of Ventilation Heterogeneity

Airway muscle tone.

It is clear that the respiratory gases have the potential to alter regional ventilation under some circumstances (reviewed in 52), either by direct effects on the airways or by alterations in local V̇a/Q̇ ratio. In animals studied at FRC, the resting (baseline) size of the airways does not represent full relaxation of airway smooth muscle and there is marked variation in the degree of airway tone, which is under vagal control (see 9 for review). MBW studies in healthy humans have shown that administration of atropine markedly decreases static lung recoil, increases series dead space, and increases ventilation heterogeneity (14), in particular in the conducting airways. The effect that a stimulus has on the airway smooth muscle is influenced by both tidal volume and end-expiratory lung volume (10). Thus there is potential for stimuli to either increase local ventilation or decrease it depending on the type of stimulus and the resting tone of the airway smooth muscle.

Effects of O2 and CO2.

The effects of altered oxygen per se on the airways have equally conflicting data in the literature. Hypoxia has been shown to locally relax airway smooth muscle in humans (36) and in some animal studies (59). Hypoxia has also been shown to increase airways resistance (29) and decrease collateral ventilation in dogs (54). The mechanisms of the effects are not well understood, but may be mediated by the extent of vagal tone (2, 39), or by associated changes in local CO2.

The effects of alterations in CO2 on the airways show conflicting data depending on the species studied, e.g., how local CO2 is altered and acid base status among other factors (52). Hyperventilation causes bronchoconstriction (55) and acts on the airway smooth muscle from the level of the trachea to the distal airways (15). The effects are rapid and onset of the effect is within seconds, with a half-life of ~1 min (52). Interestingly, the effects of low concentrations of inhaled CO2 are also bronchoconstricting in most species (52).

Another possible effect of altered inspired oxygen is on the pulmonary vasculature, whereby hypoxia would be expected to increase and hyperoxia to decrease any hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, altering the local V̇a/Q̇ ratio in lung units where HPV was altered. When breathing hyperoxic gas in the presence of HPV the local V̇a/Q̇ ratio will fall as HPV is attenuated, and V̇a/Q̇ mismatch will worsen. As oxygen uptake continues, local nitrogen and CO2 concentration will be increased and an alveolar-arterial difference for nitrogen will develop. This will have the effect of increasing the apparent ventilation heterogeneity. There are also indirect effects as altering the local V̇a/Q̇ ratio will affect local CO2 concentrations and thus potentially local lung mechanics and ventilation (22, 23). It should be noted, however, that the activity of HPV in the healthy lung may be minimal (1).

Effects of altered on the ventilation distribution.

Based on the above information hypoxia might be expected to increase ventilation heterogeneity, and hyperoxia decrease ventilation heterogeneity, consistent with an effect of oxygen on airway smooth muscle, although as discussed above indirect effects on local V̇a/Q̇ ratio are possible. In mice, with a large oxygen consumption relative to alveolar ventilation, the effects of the continued uptake of oxygen during the washout are associated with an apparent (and likely artifactual) increase in ventilation heterogeneity (19); however in the very much larger human lung this is thought to be an extremely small effect (8). In the present study in normal subjects we found no effect of either hypoxia or hyperoxia on the ventilation distribution. This was true for the global distribution of ventilation as measured by the width of the histogram distribution of ventilation as well as the Scond and Sacin indexes, representing measures of heterogeneity at the conducting airways and alveolar level. Further, because our tracer gas (10% argon) was the same in all conditions, only very minor effects associated with small changes in oxygen consumption across different values would be expected.

One possibility is that the duration of exposure to the altered gas concentration was simply too short in duration to have a significant effect on the underlying ventilation distribution. Our work is consistent with previous work by Holley et al. (33), where 133Xe was used to measure the distribution of ventilation and perfusion in upright normal subjects before and after at least 20 min of 100% oxygen breathing. There was no change in either ventilation or perfusion across three lung regions (apex, mid-lung, base) after breathing hyperoxia. Thus the previous study of Holley et al. argues against this possibility at least on a gross scale. Additionally, in the present study we conducted three MBW maneuvers for each gas concentration, and the time to wash-in was ~180 s (Fig. 1). The time between measures was ~3–4 min and the expired argon concentration before the subsequent test began was indistinguishable from that in room air. Further, we found no time-dependent effect of the three repeated exposures to the different oxygen concentrations.

Effects of altered oxygen concentration on dead space and FRC.

Dead space was significantly less in hypoxia and normoxia, compared with hyperoxia, but dead space was not different between hypoxia and normoxia in these subjects. Cardiac output is known to decrease in hyperoxia (6) which is predicted to increase physiological dead space (58). In keeping with this idea, heart rate was significantly different across the three inspired oxygen concentrations, although the difference between normoxia and hyperoxia did not reach statistical significance. Additionally, any release of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction may redistribute blood flow to areas of poor ventilation away from areas of higher ventilation. This would increase the local V̇a/Q̇ ratio in these high V̇a/Q̇ regions, and thus augment alveolar dead space.

We found a significant increase in functional residual capacity (~6%) with breathing 12.5% oxygen but no significant change with 90% oxygen. Functional residual capacity is known to increase with hypoxic exposure of moderate duration (hours) (34) and this was also the case with very short exposure in the present study. Both a decrease in FRC with hyperoxia and an increase with hypoxia with short-term (~3 min) alteration of inspired oxygen has also been reported previously (28). The mechanism behind the increase in FRC in hypoxia is not clear. Several studies report an increase in residual volume with hypoxia both with exposure in the field or in altitude chambers (11, 35, 48, 53). In this context it is often attributed to an increase in extravascular fluid accumulation resulting in premature airway closure increasing closing volume (35). Given the very short exposure to hypoxia in the present study this explanation would appear to be highly improbable. Alternately, changes in the lung mechanical properties induced by effects of the altered gas on airway smooth muscle as discussed above could affect FRC (5). However, since we did not find any changes in the uniformity of the distribution of ventilation this explanation also appears unlikely. The volume of the lung at FRC is an integrated balance between lung tissue mechanical factors and the chest wall mechanics; factors affecting respiratory muscle tension and length could alter FRC. Stimulation of peripheral chemoreceptors, such as would be expected with breathing altered inspired oxygen, is known to affect respiratory muscle activation. For example hypoxia stimulation of chemoreceptors in the presence of hypocapnia inhibits expiratory muscles (49, 50) and this may be a mechanism for the increase in FRC we observed, but since frequency and tidal volume were controlled this also is unlikely.

Implications for MBW testing and imaging studies.

The results of this study have implications not only for MBW testing but also for MR imaging studies that use oxygen as a contrast agent. One such technique, specific ventilation imaging (47), uses 20 breaths of 100% oxygen alternating with 20 breaths of air in a repeated block design. In essence specific ventilation imaging is a spatially resolved MBW. The results of the present work suggest that the use of 100% oxygen in this context does not change the underlying ventilation distribution or ventilation heterogeneity in normal subjects. However, an important consideration is the effect on FRC. Specific ventilation is the ratio of tidal volume to functional residual capacity, and the changes in local FRC may not occur uniformly in the lung.

Limitations

Number of subjects.

Whenever a study returns a largely negative result, a reasonable question is to what extent inadequate statistical power played a role in the findings. We employed a repeated measures design in this study, whereby each subject acts as his or her own control. We powered our study to detect a 5% change in MBW parameters to ensure adequate statistical power to detect a difference with the different inspired oxygen concentration. For example, for the width of the MBW distribution, we expect a test retest correlation of ~R = 0.8 based on previous studies in our laboratory, and a standard deviation of measurements in a healthy normal population of ~0.09. To detect a 5% change at a power of > 0.95, 6 subjects are required, and thus our sample size is more than adequate. In order for the observed difference in histogram width between normoxia and hyperoxia to be statistically significant in a larger population at P < 0.05, post hoc power calculations reveal that at least 282 subjects would be required. Thus any difference is between conditions is biologically very small.

Subject population.

In this study we studied normal subjects, where hypoxia has been previously shown to locally relax airway smooth muscle (36). On the other hand, in patients with COPD, the opposite has been found and breathing 30% oxygen for 20 min acts to decrease airways resistance (2, 39) also apparently by an effect on large airways (39). In normal subjects with healthy lungs and relatively uniform gas exchange it is expected that the activity of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction is minimal (1). Consequently care must be taken not to extrapolate the results of this study to patients with lung disease, as the changes in ventilation heterogeneity breathing-altered oxygen concentrations may be larger or smaller than those observed in normal subjects.

Lack of spatial information.

MBW is a sensitive technique for evaluating the heterogeneity of ventilation (44), but a limitation is that it gives a global assessment of the extent of heterogeneity present in the lung. For this reason, we cannot be certain that while the overall extent of heterogeneity is unchanged, the spatial location of lung units contributing to the heterogeneity is unchanged across conditions. However, it is difficult to imagine that large-scale changes could occur without disrupting the overall extent of heterogeneity, and thus this effect if any is probably small.

Use of automated software.

To determine Sacin and Scond, we used automated software to detect the transition from phase II to III and to calculate the phase III slope. Since we had a change in dead space volume in hyperoxia compared with normoxia and hypoxia, this may alter the volume where the transition from phase II to phase III takes place thus potentially altering the volume over which the phase III slope is evaluated. The potential effects of this uncertainty has been modeled by Stuart-Andrews et al. (51), allowing the magnitude of any error to be assessed. In the present study, the dead space changed from 170 ml in normoxia to 202 ml in hyperoxia representing a 18.8% difference. Since a volume equivalent to 50% of the phase II volume is added to the phase II/III breakpoint transition this represents on average an 9% difference in the starting point for the calculation of the phase III slope. Stuart-Andrews et al. (51) showed that a 9% difference in starting point results in a <2% error in the assessment of phase III slope. Thus any potential effect of this is very small and unlikely to be of biological significance. It should be noted that this limitation does not affect other metrics such as histogram width, lung clearance index, or curvilinearity.

Conclusions

There is no evidence from the present study that short-term (seconds to minutes) exposure to oxygen concentrations from 0.125–0.90 affects the spatial distribution of ventilation in normal subjects. However, both dead space and FRC are altered. Hyperoxia can be used in MBW and imaging studies but may alter dead space and FRC.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-118539, HL-104118, HL-119263, HL-122753, HL-129990, and HL-119201.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.R.H., G.K.P., and C.D. conceived and designed research; S.R.H., A.R.E., G.K.P., and C.D. performed experiments; S.R.H., A.R.E., and C.D. analyzed data; S.R.H., A.R.E., G.K.P., and C.D. interpreted results of experiments; S.R.H. and C.D. prepared figures; S.R.H. and C.D. drafted manuscript; S.R.H., A.R.E., G.K.P., and C.D. edited and revised manuscript; S.R.H., A.R.E., G.K.P., and C.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arai TJ, Henderson AC, Dubowitz DJ, Levin DL, Friedman PJ, Buxton RB, Prisk GK, Hopkins SR. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction does not contribute to pulmonary blood flow heterogeneity in normoxia in normal supine humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 106: 1057–1064, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90759.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astin TW, Penman RW. Airway obstruction due to hypoxemia in patients with chronic lung disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 95: 567–575, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aurora P. Multiple-breath inert gas washout test and early cystic fibrosis lung disease. Thorax 65: 373–374, 2010. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.132100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aurora P, Gustafsson P, Bush A, Lindblad A, Oliver C, Wallis CE, Stocks J. Multiple breath inert gas washout as a measure of ventilation distribution in children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 59: 1068–1073, 2004. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.022590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bancalari E, Clausen J. Pathophysiology of changes in absolute lung volumes. Eur Respir J 12: 248–258, 1998. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12010248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barratt-Boyes BG, Wood EH. Cardiac output and related measurements and pressure values in the right heart and associated vessels, together with an analysis of the hemo-dynamic response to the inhalation of high oxygen mixtures in healthy subjects. J Lab Clin Med 51: 72–90, 1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates JH, Prisk GK, Tanner TE, McKinnon AE. Correcting for the dynamic response of a respiratory mass spectrometer. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 55: 1015–1022, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bélanger J, Cormier Y. Relative contributions of gas exchange and gravity-related N2 gradients on the slope of phase III of SB-N2. Lung 160: 37–44, 1982. doi: 10.1007/BF02719270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown R, Mitzner W. Heterogeneity in airways. In: Complexity in Structure and Function of the Lung, edited by Hlastala M, Robertson H. Bethesda, MD: Dekker, 1998, p. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown RH, Mitzner W. Effect of lung inflation and airway muscle tone on airway diameter in vivo. J Appl Physiol (1985) 80: 1581–1588, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coates G, Gray G, Mansell A, Nahmias C, Powles A, Sutton J, Webber C. Changes in lung volume, lung density, and distribution of ventilation during hypobaric decompression. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 46: 752–755, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comroe JH Jr, Fowler WS. Lung function studies. VI. Detection of uneven alveolar ventilation during a single breath of oxygen. Am J Med 10: 408–413, 1951. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(51)90285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford AB, Makowska M, Paiva M, Engel LA. Convection- and diffusion-dependent ventilation maldistribution in normal subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985) 59: 838–846, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford AB, Makowska M, Engel LA. Effect of bronchomotor tone on static mechanical properties of lung and ventilation distribution. J Appl Physiol (1985) 63: 2278–2285, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croxton TL, Lande B, Hirshman CA. Role of intracellular pH in relaxation of porcine tracheal smooth muscle by respiratory gases. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 268: L207–L213, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cumming G, Jones JG. The construction and repeatability of lung nitrogen clearance curves. Respir Physiol 1: 238–248, 1966. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(66)90020-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson A. Regional pulmonary blood flow in sitting and supine man during and after acute hypoxia. J Clin Invest 48: 301–310, 1969. doi: 10.1172/JCI105986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson CA. Role of pulmonary vasomotion in physiology of the lung. Physiol Rev 64: 544–616, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dharmakumara M, Prisk GK, Royce SG, Tawhai M, Thompson BR. The effect of gas exchange on multiple-breath nitrogen washout measures of ventilation inhomogeneity in the mouse. J Appl Physiol (1985) 117: 1049–1054, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00543.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downie SR, Salome CM, Verbanck S, Thompson B, Berend N, King GG. Ventilation heterogeneity is a major determinant of airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma, independent of airway inflammation. Thorax 62: 684–689, 2007. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.069682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebina M, Yaegashi H, Takahashi T, Motomiya M, Tanemura M. Distribution of smooth muscles along the bronchial tree. A morphometric study of ordinary autopsy lungs. Am Rev Respir Dis 141: 1322–1326, 1990. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.5_Pt_1.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emery MJ, Eveland RL, Kim SS, Hildebrandt J, Swenson ER. CO2 relaxes parenchyma in the liquid-filled rat lung. J Appl Physiol (1985) 103: 710–716, 2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00128.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emery MJ, Eveland RL, Min J-H, Hildebrandt J, Swenson ER. CO2 relaxation of the rat lung parenchymal strip. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 186: 33–39, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fowler W, Cornish E, Kety S. Measurement of alveolar ventilatory components. Am J Med Sci 220: 112–113, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler W, Cornish E, Kety S. Measurement of uneven alveolar ventilation. Am J Physiol 163: 711–711, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler WS. Lung function studies; the respiratory dead space. Am J Physiol 154: 405–416, 1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fowler WS, Cornish ER Jr, Kety SS. Lung function studies. VIII. Analysis of alveolar ventilation by pulmonary N2 clearance curves. J Clin Invest 31: 40–50, 1952. doi: 10.1172/JCI102575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garfinkel F, Fitzgerald RS. The effect of hyperoxia, hypoxia and hypercapnia on FRC and occlusion pressure in human subjects. Respir Physiol 33: 241–250, 1978. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(78)90073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green M, Widdicombe JG. The effects of ventilation of dogs with different gas mixtures on airway calibre and lung mechanics. J Physiol 186: 363–381, 1966. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guy HJ, Prisk GK, Elliott AR, Deutschman RA III, West JB. Inhomogeneity of pulmonary ventilation during sustained microgravity as determined by single-breath washouts. J Appl Physiol (1985) 76: 1719–1729, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guy HJ, Prisk GK, West JB. Pulmonary function in microgravity. Physiologist 35, Suppl: S99–S102, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson AC, Sá RC, Theilmann RJ, Buxton RB, Prisk GK, Hopkins SR. The gravitational distribution of ventilation-perfusion ratio is more uniform in prone than supine posture in the normal human lung. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 313–324, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01531.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holley HS, Dawson A, Bryan AC, Milic-Emili J, Bates DV. Effect of oxygen on the regional distribution of ventilation and perfusion in the lung. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 44: 89–93, 1966. doi: 10.1139/y66-010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurtado A, Kaltreider N, McCann WS. Respiratory adaptation to anoxemia. Am J Physiol 109: 626–637, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaeger JJ, Sylvester JT, Cymerman A, Berberich JJ, Denniston JC, Maher JT. Evidence for increased intrathoracic fluid volume in man at high altitude. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 47: 670–676, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Julià-Serdà G, Molfino NA, Furlott HG, McClean PA, Rebuck AS, Hoffstein V, Slutsky AS, Zamel N, Chapman KR. Tracheobronchial dilation during isocapnic hypoxia in conscious humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 75: 1728–1733, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei M, Ghezzo H, Chen MF, Eidelman DH. Airway smooth muscle orientation in intraparenchymal airways. J Appl Physiol (1985) 82: 70–77, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis SM, Evans JW, Jalowayski AA. Continuous distributions of specific ventilation recovered from inert gas washout. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 44: 416–423, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Libby DM, Briscoe WA, King TK. Relief of hypoxia-related bronchoconstriction by breathing 30 per cent oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis 123: 171–175, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrell NW, Nijran KS, Biggs T, Seed WA. Changes in regional pulmonary blood flow during lobar bronchial occlusion in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 86: 639–644, 1994. doi: 10.1042/cs0860639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nadel JA, Widdicombe JG. Effect of changes in blood gas tensions and carotid sinus pressure on tracheal volume and total lung resistance to airflow. J Physiol 163: 13–33, 1962. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prisk GK, Elliott AR, Guy HJ, Kosonen JM, West JB. Pulmonary gas exchange and its determinants during sustained microgravity on Spacelabs SLS-1 and SLS-2. J Appl Physiol (1985) 79: 1290–1298, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prisk GK, Elliott AR, Guy HJ, Verbanck S, Paiva M, West JB. Multiple-breath washin of helium and sulfur hexafluoride in sustained microgravity. J Appl Physiol (1985) 84: 244–252, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson PD, Latzin P, Verbanck S, Hall GL, Horsley A, Gappa M, Thamrin C, Arets HG, Aurora P, Fuchs SI, King GG, Lum S, Macleod K, Paiva M, Pillow JJ, Ranganathan S, Ratjen F, Singer F, Sonnappa S, Stocks J, Subbarao P, Thompson BR, Gustafsson PM. Consensus statement for inert gas washout measurement using multiple- and single- breath tests. Eur Respir J 41: 507–522, 2013. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00069712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson PD, Goldman MD, Gustafsson PM. Inert gas washout: theoretical background and clinical utility in respiratory disease. Respiration 78: 339–355, 2009. doi: 10.1159/000225373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sá RC, Asadi AK, Theilmann RJ, Hopkins SR, Prisk GK, Darquenne C. Validating the distribution of specific ventilation in healthy humans measured using proton MR imaging. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 1048–1056, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00982.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sá RC, Cronin MV, Henderson AC, Holverda S, Theilmann RJ, Arai TJ, Dubowitz DJ, Hopkins SR, Buxton RB, Prisk GK. Vertical distribution of specific ventilation in normal supine humans measured by oxygen-enhanced proton MRI. J Appl Physiol (1985) 109: 1950–1959, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00220.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders NA, Betts MF, Pengelly LD, Rebuck AS. Changes in lung mechanics induced by acute isocapnic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 42: 413–419, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saupe KW, Smith CA, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Respiratory muscle recruitment during selective central and peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation in awake dogs. J Physiol 448: 613–631, 1992. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith CA, Ainsworth DM, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Differential responses of expiratory muscles to chemical stimuli in awake dogs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 66: 384–391, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuart-Andrews CR, Kelly VJ, Sands SA, Lewis AJ, Ellis MJ, Thompson BR. Automated detection of the phase III slope during inert gas washout testing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 1073–1081, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00372.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swenson E, Domino K, Hlastala M. Physiological effects of oxygen and carbon dioxide on VA/Q heterogeneity. In: Complexity in Structure and Function of the Lung, edited by Hlastala M, Roberson H. Bethesda, MD: Dekker, 1998, p. 511–547. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tenney SM, Rahn H, Stroud RC, Mithoefer JC. Adoption to high altitude: changes in lung volumes during the first seven days at Mt. Evans, Colorado. J Appl Physiol 5: 607–613, 1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Traystman RJ, Batra GK, Menkes HA. Local regulation of collateral ventilation by oxygen and carbon dioxide. J Appl Physiol 40: 819–823, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van den Elshout FJ, van Herwaarden CL, Folgering HT. Effects of hypercapnia and hypocapnia on respiratory resistance in normal and asthmatic subjects. Thorax 46: 28–32, 1991. doi: 10.1136/thx.46.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verbanck S, Schuermans D, Van Muylem A, Melot C, Noppen M, Vincken W, Paiva M. Conductive and acinar lung-zone contributions to ventilation inhomogeneity in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 1573–1577, 1998. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9710042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verbanck S, Schuermans D, Van Muylem A, Paiva M, Noppen M, Vincken W. Ventilation distribution during histamine provocation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 83: 1907–1916, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wasserman K, Zhang Y-Y, Gitt A, Belardinelli R, Koike A, Lubarsky L, Agostoni PG. Lung function and exercise gas exchange in chronic heart failure. Circulation 96: 2221–2227, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.7.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wetzel RC, Herold CJ, Zerhouni EA, Robotham JL. Hypoxic bronchodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 73: 1202–1206, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]