Abstract

Pruning of unspecific neurites is an important mechanism during neuronal morphogenesis. Drosophila sensory neurons prune their dendrites during metamorphosis. Pruning dendrites are severed in their proximal regions. Prior to severing, dendritic microtubules undergo local disassembly, and dendrites thin extensively through local endocytosis. Microtubule disassembly requires a katanin homologue, but the signals initiating microtubule breakdown are not known. Here, we show that the kinase PAR‐1 is required for pruning and dendritic microtubule breakdown. Our data show that neurons lacking PAR‐1 fail to break down dendritic microtubules, and PAR‐1 is required for an increase in neuronal microtubule dynamics at the onset of metamorphosis. Mammalian PAR‐1 is a known Tau kinase, and genetic interactions suggest that PAR‐1 promotes microtubule breakdown largely via inhibition of Tau also in Drosophila. Finally, PAR‐1 is also required for dendritic thinning, suggesting that microtubule breakdown might precede ensuing plasma membrane alterations. Our results shed light on the signaling cascades and epistatic relationships involved in neurite destabilization during dendrite pruning.

Keywords: dendrite, PAR‐1, pruning, Tau

Subject Categories: Cell Adhesion, Polarity & Cytoskeleton; Neuroscience

Introduction

The physiological degeneration of synapses, axons, or dendrites without loss of the parent neuron is known as pruning. Pruning is an important developmental mechanism that is used to ensure specificity of neuronal connections, and to remove developmental intermediates (Luo & O'Leary, 2005; Schuldiner & Yaron, 2015). While the mechanisms of neurite outgrowth and synapse formation have been studied in some detail, comparably little is known about the mechanisms underlying pruning.

In holometabolous insects, the nervous system is remodeled at a large scale during metamorphosis. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS) of Drosophila, several types of sensory neurons undergo either apoptosis or prune their larval processes in an ecdysone‐dependent manner. The sensory class IV dendritic arborization (c4da) neurons completely and specifically prune their long and branched larval dendrites at the onset of the pupal phase, while their axons stay intact (Kuo et al, 2005; Williams & Truman, 2005). Pruning proceeds in a stereotypical fashion: Dendrites are first severed at proximal sites close to the cell body between 5 and 10 h after puparium formation (h APF). Severed dendrites are then fragmented and phagocytosed by the epidermal cells surrounding them (Han et al, 2014). First signs of dendrite pruning are visible at 2–3 h APF when dendrites start to display swellings and thinned regions in their proximal parts where they are subsequently severed. Proximal dendrites are destabilized by local disassembly of the cytoskeleton through the microtubule‐severing enzyme Katanin p60‐like 1 (Kat‐60L1) (Lee et al, 2009) and possibly the actin‐severing enzyme Mical (Kirilly et al, 2009). Furthermore, the plasma membrane of proximal dendrites is thinned through increased local endocytosis (Kanamori et al, 2015).

How proximal dendrite destabilization is orchestrated is one of the most intriguing questions in the field. Local microtubule breakdown is one of the first apparent signs of pruning before plasma membrane severing in dendrites (Williams & Truman, 2005; Lee et al, 2009). However, not much is known about the signals leading to microtubule breakdown. For example, Kat‐60L1 is already expressed at the larval stage in c4da neurons (Stewart et al, 2012), opening up the question as to how it is activated temporally for dendrite pruning.

Here, we show that the kinase PAR‐1 is required for dendrite pruning and dendritic microtubule breakdown. PAR‐1 is known to phosphorylate microtubule‐associated proteins (MAPs) including Tau, thus leading to microtubule destabilization (Drewes et al, 1997). We found that PAR‐1 is required for an increase in c4da neuron microtubule dynamics during the early pupal phase. Furthermore, we found that PAR‐1 interacts genetically with Drosophila Tau in a manner consistent with Tau being a PAR‐1 target during dendrite pruning. Tau is also known to inhibit katanin (Qiang et al, 2006), and we found that PAR‐1 interacts genetically with Kat‐60L1. Finally, local microtubule breakdown is linked to loss of membrane stabilizing factors and dendritic membrane collapse. Thus, our results suggest a mechanism for local microtubule disassembly and the relationship between early local events during pruning.

Results

Drosophila PAR‐1 is required for sensory neuron dendrite pruning

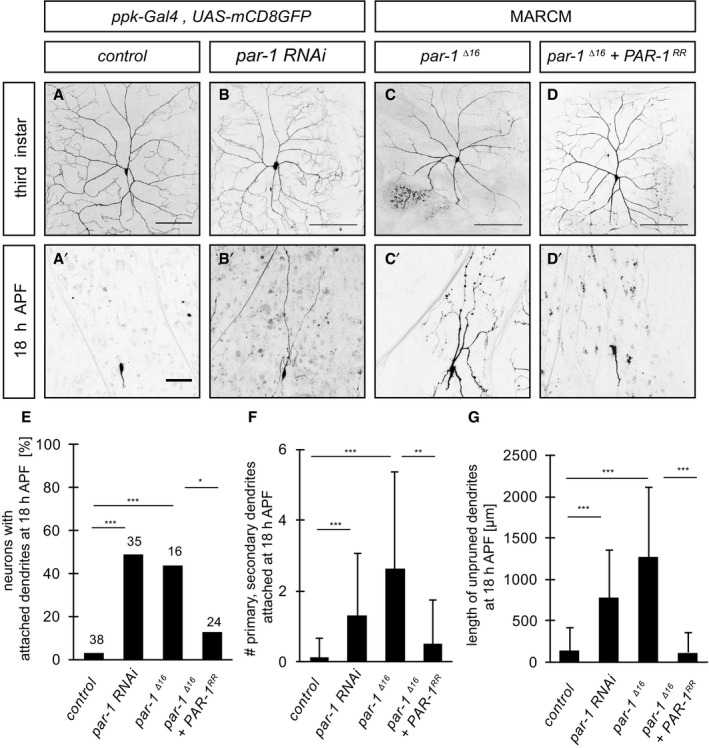

Drosophila c4da neurons have long and branched dendrites at the larval stage (Fig 1A), which are pruned completely during the first 18 h of the pupal phase (Fig 1A′). We used the GAL4 driver pickpocket‐GAL4 (ppk‐GAL4) to express transgenic RNAi in c4da neurons and to screen for pruning factors. We found that loss of the protein kinase PAR‐1 leads to dendrite pruning defects. par‐1 RNAi had little effect on larval c4da neuron morphology (Fig 1B) and no change to the axonal projections in the ventral nerve cord (Appendix Fig S1). However, par‐1 RNAi caused a significant fraction of c4da neurons to retain dendrites attached to the cell body at 18 h APF (Fig 1B′). Because strong par‐1 loss‐of‐function alleles like par‐1 Δ16 (Cox et al, 2001) are embryonic lethal, we used MARCM (mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker) (Lee & Luo, 1999) a mitotic recombination technique, to generate fluorescently labeled homozygous par‐1 Δ16 mutant clones in otherwise heterozygous animals. Homozygous par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neurons exhibited similarly strong dendrite pruning defects (Fig 1C and C′). Importantly, these pruning defects could be rescued by GAL4/UAS‐mediated expression of PAR‐1 in par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neurons (Fig 1D and D′). Thus, PAR‐1 is required for sensory neuron dendrite pruning in the Drosophila PNS.

Figure 1. PAR‐1 is required for sensory neuron dendrite pruning.

-

A–D′Loss of PAR‐1 causes defects in c4da neuron dendrite pruning. Upper panels (A–D) show third‐instar larval neurons, and lower panels (A′–D′) show neurons at 18 h APF. (A, A′) Control c4da neurons labeled by UAS‐CD8GFP expression under the control of ppk‐GAL4 (third chromosome insertion). (B, B′) C4da neurons expressing par‐1 RNAi under ppk‐GAL4. (C, C′) MARCM clones of par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neurons. (D, D′) Rescue of par‐1 Δ16 mutant MARCM c4da neuron pruning defects by UAS‐mediated expression of wild‐type PAR‐1 (isoform RR).

-

EPercentages of neurons with dendrite pruning defects. ***P < 0.0005, *P < 0.05 (using Fisher's exact test). N = 16–38.

-

FNumber of attached primary and secondary dendrites at 18 h APF. ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005 (using Wilcoxon's test). N = 16–38.

-

GLength of unpruned dendrites at 18 h APF. ***P < 0.0005 (using Wilcoxon's test). N = 16–38.

PAR‐1 affects microtubule breakdown and dynamics during the early pupal phase

PAR‐1 is known for its roles in the regulation of cell polarity and in the regulation of microtubule stability. Two independent RNAi lines against bazooka (Baz), a well‐defined PAR‐1 substrate in the polarity pathway (Benton & St Johnston, 2003), did not cause pruning defects (Appendix Fig S2). par‐1 RNAi did also not affect expression of Sox14, an ecdysone receptor target, during dendrite pruning (Kirilly et al, 2009) (Appendix Fig S2).

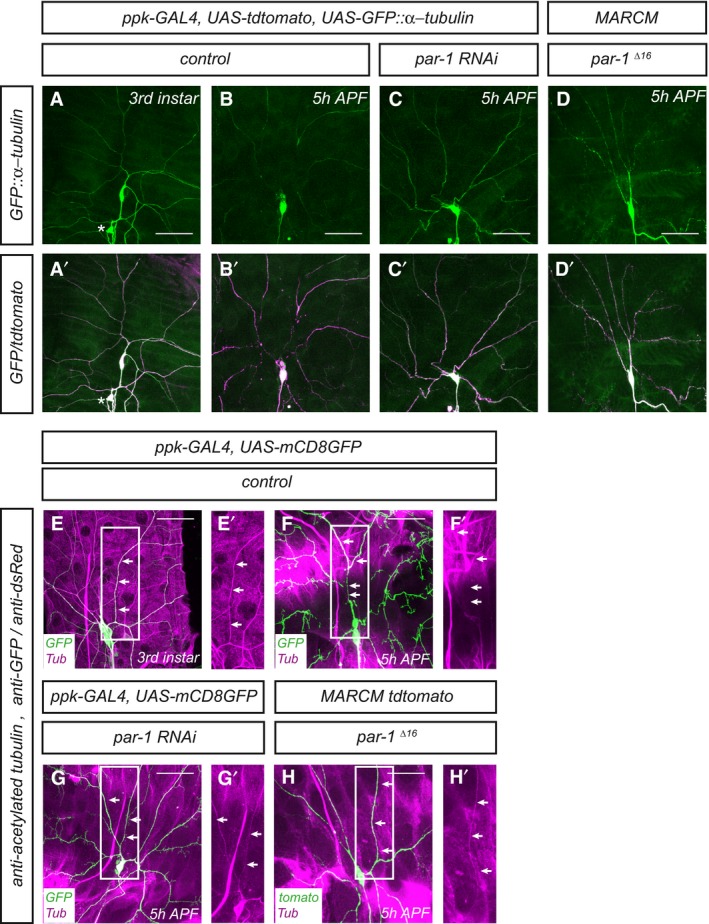

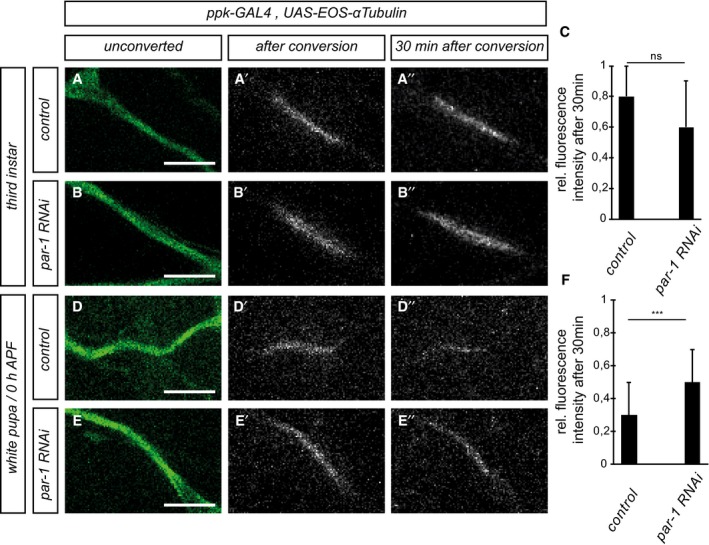

Disassembly of dendritic microtubules during the early pupal stage is one of the first detectable changes during c4da neuron dendrite pruning before severing (Williams & Truman, 2005; Lee et al, 2009). In order to assess effects on microtubules in pruning c4da neurons, we expressed GFP‐tagged α‐tubulin (GFP::α‐tubulin) in c4da neurons and visualized it by immunofluorescence. Major dendritic branches showed continuous GFP signal at the third‐instar larval stage (Fig 2A and A′). At 5 h APF, when most dendrites are still attached to the soma, clear gaps in the GFP::α‐tubulin were visible in the proximal dendrites, indicating the loss of microtubules (Fig 2B and B′). In contrast, c4da neurons expressing par‐1 RNAi, or par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neurons exhibited uninterrupted GFP::α‐tubulin staining at 5 h APF (Fig 2C–D′), suggesting that PAR‐1 might affect microtubule breakdown in pruning dendrites. Microtubule stability and dynamics can be assessed by looking at microtubule posttranslational modifications (Brill et al, 2016; Tao et al, 2016). At 5 h APF, acetylated α‐tubulin, which reflects stable microtubules, was lost from proximal dendrites in control neurons (Fig 2E and F), but persisted in neurons expressing par‐1 RNAi or in par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neurons (Fig 2G and H). Polyglutamylated α‐tubulin, another marker for stable microtubules, showed a similar distribution (Appendix Fig S3). To assess microtubule dynamics more directly, we next took a photoconversion approach (Tao et al, 2016). To this end, we expressed α‐tubulin tagged with photoconvertible EOS (tdEOS::α‐tubulin) in c4da neurons and used a 405‐nm laser to convert it from green to red in a defined stretch of proximal dendrite. We then assessed after 30 min what fraction of the converted EOS was still present at the converted site. In dendrites of third‐instar c4da neurons, we found that photoconverted EOS decayed slowly, and at a similar rate between control neurons and neurons expressing par‐1 RNAi (Fig 3A–C), thus indicating relatively stable microtubules. When we assessed the decay of converted EOS::α‐tubulin at the onset of the pupal phase (0 h APF), converted EOS::α‐tubulin decayed much faster than at the larval stage, indicating an increase in microtubule dynamics (Fig 3D and F). Furthermore, par‐1 RNAi now caused the converted EOS::α‐tubulin to decay significantly more slowly than in controls (Fig 3E and F). Thus, while PAR‐1 does not seem to affect microtubule dynamics at the larval stage, it is required for an increase in microtubule dynamics at the onset of the pupal phase. Together with the observation that loss of PAR‐1 leads to more stable microtubules, these data suggest that PAR‐1 specifically destabilizes microtubules for dendrite pruning.

Figure 2. PAR‐1 is required for dendritic microtubule breakdown during the early phase of c4da neuron dendrite pruning.

-

A–D′Microtubules were labeled by expression of UAS‐GFP::α‐tubulin in c4da neurons under ppk‐GAL4, and c4da neuron morphology was visualized by UAS‐tdtomato. Panels (A–D) show GFP::α‐tubulin staining, and panels (A′–D′) show the merge with tdtomato. (A, A′) Third‐instar control c4da neuron. The asterisk denotes a c3da neuron that is also sometimes labeled by the ppk‐GAL4 driver. (B, B′) Control c4da neuron at 5 h APF. GFP signal disappears from proximal dendrite regions. (C, C′) C4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi at 5 h APF. (D, D′) par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neuron MARCM clone at 5 h APF. Continuous GFP staining persists in proximal dendrites after loss of PAR‐1.

-

E–H′Microtubules were labeled by an antibody against acetylated α‐tubulin, and c4da neuron morphology was visualized by UAS‐CD8GFP expressed under ppk‐GAL4, or by tdtomato in MARCM clones. Panels (E–H) show merges of the indicated genotypes, and panels (E′–H′) show only the acetylated α‐tubulin signal of the boxed regions in (E–H). Arrows indicate the positions of dendrites. (E, E′) Third‐instar control c4da neuron. (F, F′) Control c4da neuron at 5 h APF. (G, G′) C4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi at 5 h APF. (H, H′) par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neuron MARCM clone at 5 h APF.

Figure 3. PAR‐1 is required for increased microtubule dynamics in c4da neurons at the onset of the pupal phase.

-

A–A″Third‐instar control c4da neuron.

-

B–B″Third‐instar c4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi.

-

CQuantification of remaining red tdEOS::α‐tubulin in panels (A and B). N was 18 (control) and 15 (par‐1 RNAi), respectively. P = 0.098, Wilcoxon's test.

-

D–D″White pupal control c4da neuron (0 h APF).

-

E–E″White pupal c4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi (0 h APF).

-

FQuantification of remaining red tdEOS in panels (D and E). N was 34 (control) and 35 (par‐1 RNAi). ***P < 0.0005, Wilcoxon's test.

PAR‐1 is linked to Drosophila Tau during dendrite pruning

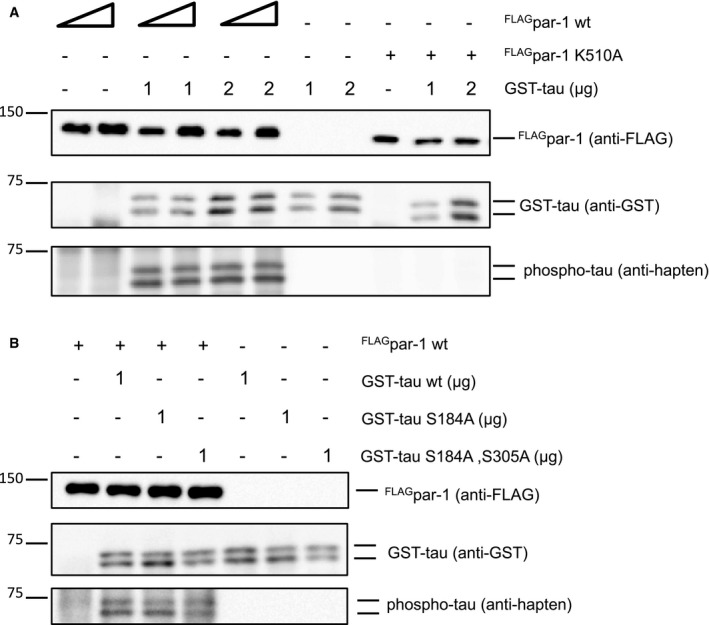

The best‐characterized microtubule‐associated protein target for vertebrate PAR‐1 is Tau (Drewes et al, 1997), and Drosophila Tau has also been shown to be phosphorylated by PAR‐1 (Doerflinger et al, 2003). Using purified recombinant proteins, we confirmed that PAR‐1 phosphorylates Drosophila Tau (Fig EV1). In order to assess endogenous Tau expression in peripheral sensory neurons, we used a MiMIC‐derived GFP insertion line that produces a Tau::GFP fusion protein from the endogenous locus (Nagarkar‐Jaiswal et al, 2015). At the third‐instar larval stage, Tau::GFP was strongly expressed in all larval da neurons (Fig 4A) and localized to both c4da neuron axons and dendrites (Fig 4A and A′). At 5 h APF, the Tau::GFP signal was lower in da neuron dendrites while it was unchanged in axons (Fig 4 B and B′). In order to specifically detect Tau distribution in c4da neurons, we next expressed HA‐tagged Tau (TauHA) under the ppk‐GAL4 driver. Like endogenous Tau, TauHA was distributed evenly along the major dendritic branches in larval c4da neurons (Fig 4C and C′), and at 5 h APF, the TauHA staining in the dendrites had largely disappeared (Fig 4D and D′). However, par‐1 RNAi prevented the disappearance of TauHA from dendrites (Fig 4E and E′), and TauHA could also still be seen in dendrites of par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neurons (Fig 4F and F′). We also assessed the distribution of Futsch/MAP1B, a MAP that is highly expressed in Drosophila larval peripheral neurons (Fujita et al, 1982, Hummel et al, 2000). Futsch distribution closely resembles the distribution of microtubules, and it is therefore often used as a microtubule marker in fly PNS neurons. Similar to Tau, Futsch was lost from thinned proximal c4da neuron dendrites at 5 h APF, but persisted at 5 h APF in dendrites in neurons expressing par‐1 RNAi, or in par‐1 Δ16 mutant MARCM c4da neurons (Fig EV2).

Figure EV1. PAR‐1 phosphorylates Drosophila tau .

- The indicated combinations of recombinant FLAGPAR‐1 (isoform RR, wild‐type, or kinase‐dead K510A) from S2 cells and bacterially expressed GST‐tau were incubated with ATPγS, and thiophosphorylated proteins were detected after alkylation with an antibody against a semisynthetic thiophosphate epitope (anti‐hapten) (Allen et al, 2007).

- Phosphoassay with wild‐type FLAGPAR‐1 and the indicated GST‐tau phosphomutants.

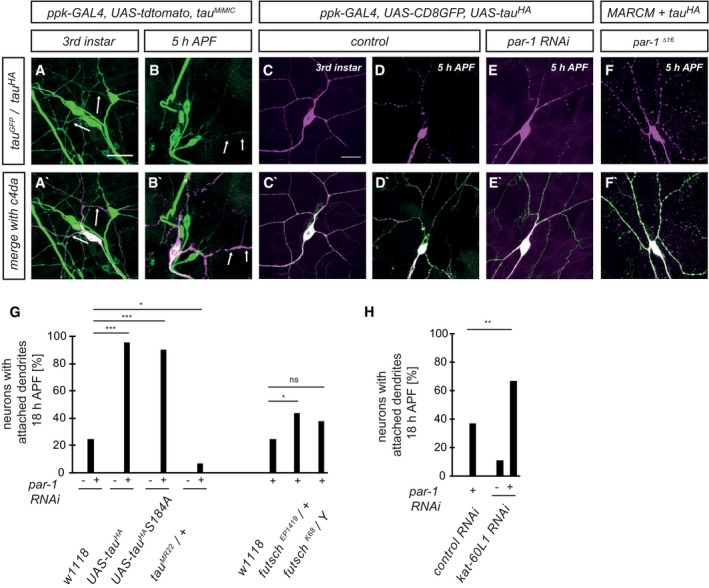

Figure 4. Tau distribution in da neurons and genetic interactions with PAR‐1 during dendrite pruning.

-

A–B′Endogenous Tau was visualized using a MiMIC‐derived Tau::GFP fusion protein. Arrows mark c4da neuron dendrites. (A, A′) Endogenous Tau localizes to axons and dendrites in third‐instar c4da neurons. (B, B′) Tau is reduced in dendrites at 5 h APF.

-

C–F′Tau distribution in c4da neurons using transgenic HA‐tagged Tau. Neurons were labeled by UAS‐CD8GFP under ppk‐GAL4 (C–E) or by UAS‐tdtomato in MARCM clones (F). (C, C′) TauHA staining in a third‐instar control neuron. (D, D′) TauHA staining in a control neuron at 5 h APF. (E, E′) TauHA distribution in a c4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi at 5 h APF. (F, F′) TauHA distribution in par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neuron at 5 h APF.

-

GSpecific dosage‐dependent genetic interactions between par‐1 and tau. Effects of Tau or Futsch upregulation (UAS‐TauHA, UAS‐TauHA S184A, futsch EP1419) or downregulation (tau MR22/+, futsch K68 /Y) on dendrite pruning defects induced by par‐1 RNAi at 18 h APF. All transgenes were expressed under the control of a second chromosome insertion of ppk‐GAL4. ***P < 0.0005, *P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test, N = 23–48.

-

HGenetic interactions between par‐1 and kat‐60L1. par‐1 RNAi was coexpressed with Or83b RNAi as a control, or with kat‐60L1 RNAi, and the effects on dendrite pruning were assessed at 18 h APF. **P < 0.005, Fisher's exact test. N = 38–49.

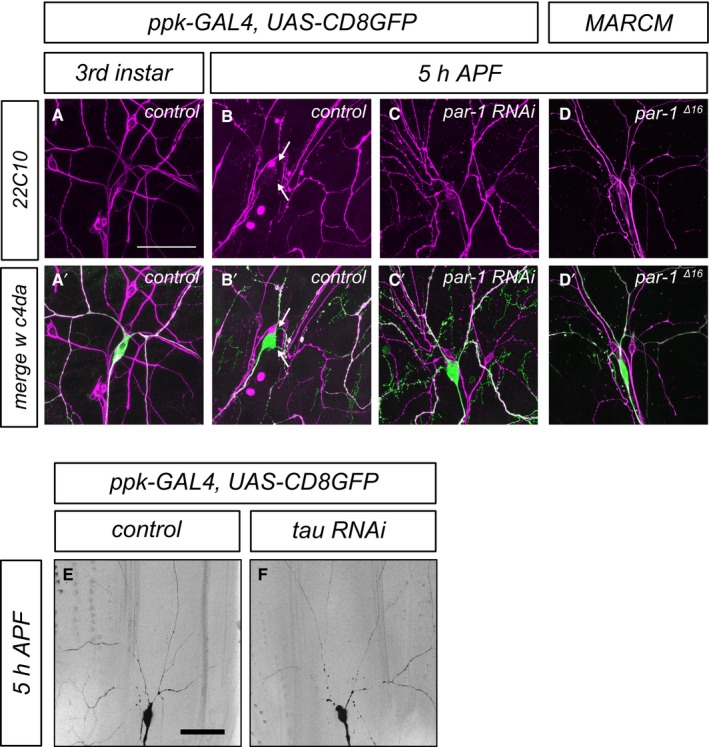

Figure EV2. Futsch/MAP1B distribution during c4da neuron dendrite pruning and effects of tau depletion on dendrite pruning.

-

A–D′Futsch/22C10 distribution in c4da neurons. Panels (A–D) show Futsch/22C10 staining, and panels (A′–D′) show the merge with the c4da neuron marker (ppk>CD8GFP in A–C, tdtomato in D). (A, A′) Control c4da neuron at the third‐instar larval stage. (B, B′) Control c4da neuron at 5 h APF. Futsch/22C10 is lost from proximal dendrites (arrows). (C, C′) A c4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi at 5 h APF still shows strong dendritic Futsch/22C10. (D, D′) A par‐1 Δ16 mutant MARCM c4da neuron at 5 h APF still shows strong dendritic Futsch/22C10.

-

E, Ftau RNAi does not trigger precocious dendrite pruning at 5 h APF. Representative images of control c4da neurons (E) or c4da neurons expressing tau RNAi under the control of ppk‐GAL4 (F) are shown.

We next employed a genetic test to see whether PAR‐1 and these MAPs might act in a common pathway during dendrite pruning. To this end, we tested whether manipulation of MAP levels could modify the pruning defects caused by par‐1 RNAi (Fig 4G). Here, we chose a combination of a ppk‐GAL4 insertion and par‐1 RNAi that caused intermediate penetrance pruning defects that could be both enhanced and suppressed (20–30% of neurons with attached dendrites at 18 h APF). Overexpression of tau HA did not cause pruning defects by itself, but strongly enhanced the dendrite pruning defects caused by par‐1 RNAi (Fig 4G). Conversely, removal of one copy of tau with the small deficiency tau MR22 (Doerflinger et al, 2003) led to a significant suppression of the par‐1 RNAi phenotype (Fig 4G). In contrast, Futsch overexpression only led to a very mild increase in the pruning defects induced by par‐1 RNAi, and a futsch mutation did not suppress the pruning defects (Fig 4G). Thus, the strong and specific genetic interactions between par‐1 and tau, and especially the fact that a reduction of Tau levels can suppress par‐1 pruning defects, suggest that Tau is a target for PAR‐1 during dendrite pruning.

In human Tau, serines 262 and 356 are major PAR‐1 phosphorylation sites. Phosphorylation at position 262 in particular releases hTau from microtubules (Biernat et al, 1993). Drosophila Tau serine 184 is the closest analogue to serine 262 in human Tau. If this site was a major phosphorylation site during dendrite pruning, then a serine 184 mutation to alanine (S184A) would be expected to be resistant to inhibition, and to cause dominant dendrite pruning defects similar to those upon par‐1 downregulation. However, overexpression of tau HA S184A did not cause dendrite pruning defects and enhanced par‐1 RNAi to the same extent as wild‐type tau HA, indicating that inhibition of S184 phosphorylation is not sufficient to inhibit pruning (Fig 4G). Furthermore, recombinant PAR‐1 was still able to phosphorylate Tau variants lacking serines 184 and 305 (analogous to hTau serine 356) in vitro (Fig EV1). Thus, we speculate that the phosphorylation sites in Drosophila Tau might be different from the ones in human Tau.

It has previously been shown that Tau is a potent katanin antagonist (Qiang et al, 2006). Since the katanin homolog Kat‐60L1 is required for dendrite pruning (Lee et al, 2009), this opens up the possibility that PAR‐1 activates Kat‐60L1 via regulation of Tau. To investigate this possibility, we asked if kat‐60L1 RNAi could modify the pruning defects induced by par‐1 RNAi. kat‐60L1 RNAi alone caused only modest pruning defects (Fig 4H). However, when par‐1 RNAi was coexpressed with kat‐60L1 RNAi, significantly more c4da neurons retained dendrites at 18 h APF than when par‐1 RNAi was coexpressed with a or83b control RNAi, and more than the combined added effects of the single par‐1 and kat‐60L1 RNAis, indicating that kat‐60L1 acts as an enhancer of the par‐1 pruning defects (Fig 4H). Taken together, our genetic data are consistent with a model where PAR‐1 alters microtubule dynamics during dendrite pruning via inhibition of Tau, thus enhancing microtubule accessibility to katanin.

PAR‐1 also regulates c1da neuron dendrite pruning in a Tau‐dependent manner

A second type of peripheral sensory neurons, the class 1 da (c1da) neurons, also prune their somewhat simpler dendritic arbors with a similar time course as c4da neurons (Williams & Truman, 2005) (Fig 5A and B). par‐1 Δ16 mutant c1da neurons retained larval dendrites with near‐complete penetrance (Fig 5C), and this phenotype could also be rescued by re‐expression of wild‐type PAR‐1 (Fig 5D and F). Interestingly, we observed that the PAR‐1 RR isoform (nomenclature according to flybase.org) was more potent at rescuing c1da pruning defects than the PAR‐1 RL isoform (Sun et al, 2001) (Fig 5D, F, and H), possibly indicating a degree of isoform specificity. A kinase‐dead version of PAR‐1 RL (Sun et al, 2001) did not rescue the pruning defects of the par‐1 Δ16 mutant (Fig 5G), confirming that PAR‐1 kinase activity is required for its role in dendrite pruning. Importantly, the very strong pruning defects of par‐1 Δ16 mutant c1da neurons were significantly suppressed by tau heterozygosity (tau MR22/+) (Fig 5E and H). Thus, PAR‐1 appears to act broadly in fly sensory neurons to promote dendrite pruning via microtubule destabilization.

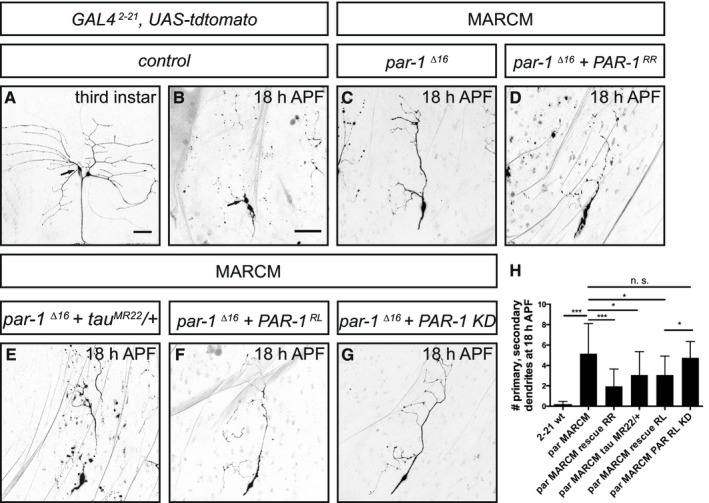

Figure 5. PAR‐1 is required for c1da neuron dendrite pruning in a tau‐sensitive manner.

- Third‐instar larval c1da neurons. The c1da neuron ddaD is marked by an arrow.

- At 18 h APF, c1da neurons have largely pruned their larval dendrites. Arrow, ddaD.

- A par‐1 Δ16 mutant c1da neuron retains its dendrites at 18 h APF.

- A par‐1 Δ16 mutant c1da neuron expressing wild‐type PAR‐1 (isoform RR).

- A par‐1 Δ16 mutant c1da neuron in a heterozygous tau MR22 /+ mutant background.

- A par‐1 Δ16 mutant c1da neuron expressing wild‐type PAR‐1 (isoform RL).

- A par‐1 Δ16 mutant c1da neuron expressing kinase‐dead PAR‐1 (isoform RL).

- Quantification of numbers of attached primary and secondary dendrites at 18 h APF (N = 13–25 for the MARCM experiments). ***P < 0.0005, *P < 0.05. n. s., not significant, P > 0.05 (using Wilcoxon's test). Error bars represent s.d.

PAR‐1 is linked to endocytosis and dendrite thinning

Proximal dendrite regions adopt a thinned and beaded morphology early during dendrite pruning. These proximal thinnings are induced by local endocytosis and act as diffusion barriers that enable local Ca2+ transients in dendrites (Kanamori et al, 2015). We wondered if PAR‐1 might be linked to, or required for, these membrane alterations. Interestingly, we found that Ank2XL, a giant neuronal ankyrin linking the plasma membrane to the cytoskeleton (Koch et al, 2008; Pielage et al, 2008), uniformly labeled neurites of larval c4da neurons, but was lost from proximal dendrites at 5 h APF (Fig 6A and B). The distribution of Ank2XL closely resembled that of the MAP and microtubule marker Futsch (Fig 6B), and Ank2XL loss was prevented by inhibition of PAR‐1 (Fig 6C and D).

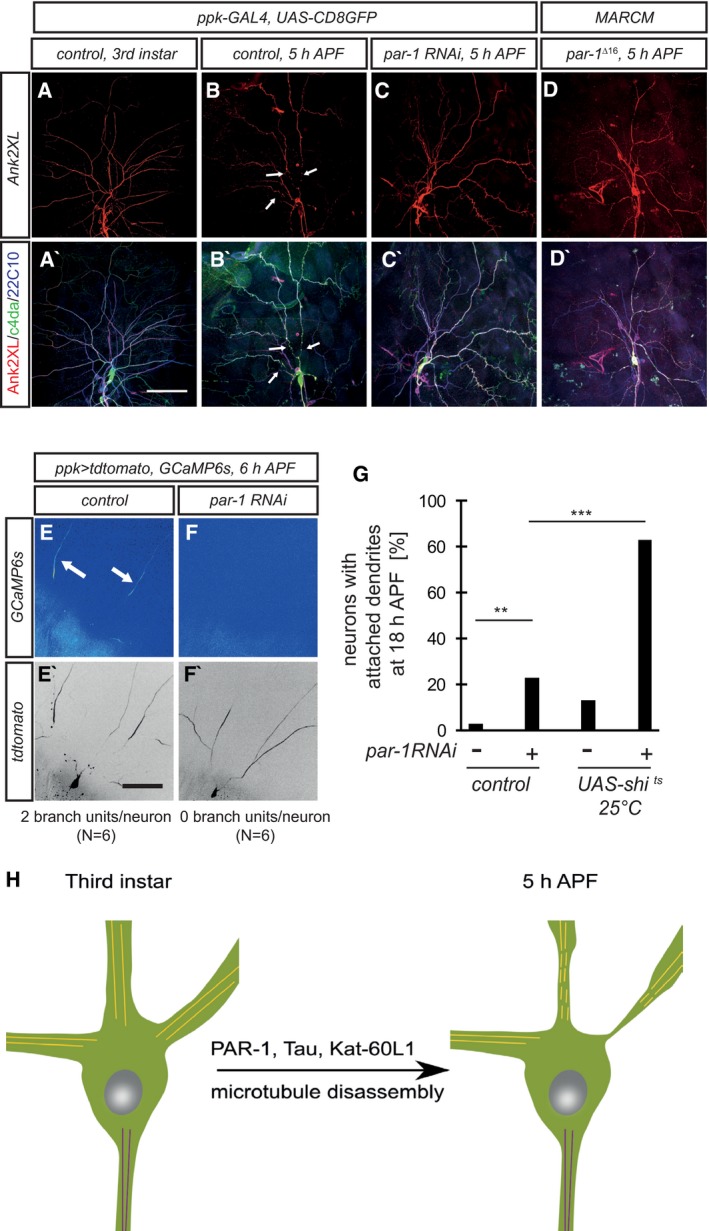

Figure 6. PAR‐1 is required for dendritic membrane alterations during pruning.

-

A–C′Ank2XL is lost from proximal dendrites in a PAR‐1‐dependent manner during the early pupal stage. Upper panels (A–C) show Ank2XL staining at the indicated developmental stages, and lower panels (A′–C′) show merge with Futsch/22C10 staining and c4da neuron markers. (A, A′) Third‐instar larval control c4da neuron. (B, B′) Control c4da neuron at 5 h APF. Arrows indicate dendrite regions devoid of Ank2XL and 22C10 staining. (C, C′) C4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi at 5 h APF.

-

D, D′par‐1 Δ16 mutant c4da neuron at 5 h APF.

-

E–F′PAR‐1 is required for dendritic Ca2+ transients during the early phase of pruning. Transgenes were expressed under ppk‐GAL4. Panels (E and F) show GCaMP6s fluorescence intensity in c4da neuron dendrites at 6 h APF, and panels (E′ and F′) show the tdtomato marker to visualize neuronal morphology. Numbers below panels indicate the average number of dendrites with independent Ca2+ transients (branch units) in a 10‐min movie (N = 6). (E, E′) Control c4da neuron. Arrows indicate dendrites with Ca2+ transients. (F, F′) C4da neuron expressing par‐1 RNAi.

-

GGenetic interactions between PAR‐1 and shibire/dynamin. Dendrite pruning defects of the indicated genotypes were analyzed at 18 h APF as in Fig 4. All flies were kept at 25°C, the permissive temperature for shi ts. ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005, Fisher's exact test. N = 48–64.

-

HModel. Activation of PAR‐1 leads to loss of c4da neuron dendritic microtubules via Tau inhibition and possibly, Kat‐60L1 activation. Microtubule loss in proximal regions precedes dendritic thinning.

We next asked whether PAR‐1 might be linked to the formation of dendrite thinnings, the barriers for compartmentalized dendritic Ca2+ transients (also called “branch units”) (Kanamori et al, 2013, 2015). We therefore used the genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor GCaMP6s to assess the effect of par‐1 RNAi on their occurence. At 6 h APF, control c4da neurons exhibited robust Ca2+ transients (Fig 6E), and we counted an average of two branch units per neuron in 5‐min timelapse recordings. Under the same conditions, expression of par‐1 RNAi completely abrogated Ca2+ transients (Fig 6F), indicating that PAR‐1 is required for Ca2+ transient formation. Finally, thinning formation also requires dynamin‐dependent local endocytosis (Kanamori et al, 2015). We tested genetically if PAR‐1 was linked to endocytosis during dendrite pruning. To this end, we expressed the temperature‐sensitive dominant dynamin mutant shibire ts in c4da neurons. At the restrictive temperature of 29°C, shibire ts inhibits dendrite thinning formation and causes strong dendrite pruning defects (Kanamori et al, 2015). At the permissive temperature of 25°C, shibire ts induced only mild pruning defects. However, the combination of shibire ts with intermediate strength par‐1 RNAi (as in Fig 4G) at 25°C led to a very strong synergistic enhancement and almost completely penetrant pruning defects (Fig 6G). Thus, PAR‐1 is required for both microtubule breakdown and local membrane destabilization during dendrite pruning. Since our genetic data have indicated that Tau is the most likely PAR‐1 target during dendrite pruning, these data suggest an epistatic relationship between microtubule breakdown and membrane thinning.

Discussion

In this work, we found that the kinase PAR‐1 is part of a pathway for microtubule disassembly during dendrite pruning. Our data show that PAR‐1 acts to enhance microtubule dynamics specifically during the early pupal phase. In the absence of PAR‐1, c4da neurons accumulate stable microtubules at a time when control neurons have already degraded most of their dendritic microtubules. Our genetic data suggest that Tau is a major target for PAR‐1 in this process and that PAR‐1 is required during pruning to remove, or inactivate Tau. It is known that Tau itself stabilizes microtubules; therefore, Tau inhibition likely serves to destabilize microtubules. Interestingly, Tau removal might also serve to activate the katanin homologue Kat‐60L1 during dendrite pruning. This is an attractive possibility because Tau, but not the Futsch homolog MAP1B, has been shown to be a potent katanin inhibitor in mammalian cells (Qiang et al, 2006), exactly matching our observed genetic interactions with PAR‐1 during dendrite pruning (Fig 4). Tau also becomes depleted from mammalian sensory neuron axons after trophic support withdrawal in an in vitro pruning model system (Maor‐Nof et al, 2013). Tau depletion was not sufficient to induce pruning in mammalian sensory neurons (Maor‐Nof et al, 2013), matching our observations in c4da neurons (Fig EV2). However, while not sufficient, it is interesting to speculate that Tau inactivation might also be required for pruning in mammalian neurons.

Our data suggest that PAR‐1 acts specifically during the pupal phase, but PAR‐1 protein levels do not seem to increase at this stage (Appendix Fig S4). PAR‐1 can be activated through phosphorylation by upstream kinases such as LKB1. lkb1 mutants showed only mild pruning defects that likely cannot fully explain the stronger defects caused by PAR‐1 downregulation (Appendix Fig S4). Interestingly, we found that PAR‐1 interacts genetically with ik2, another kinase required for dendrite pruning (Lee et al, 2009) (Appendix Fig S4). Thus, PAR‐1 activation during dendrite pruning might depend on the interplay of several kinases. Given the temporal specificity of the PAR‐1 effect (Fig 3), it is interesting to speculate that PAR‐1 might be directly activated by a ecdysone‐responsive factor.

We also found that loss of PAR‐1 prevents several processes at the dendritic plasma membrane during the pruning process: It prevented the local loss of membrane‐associated Ank2XL from proximal dendrites (Fig 6A–D′), abrogated Ca2+ transients (Fig 6E and F), and displayed strong enhancing genetic interactions with the thinning factor shibire (Fig 6G). As our genetic data indicate that Tau is the primary PAR‐1 target during dendrite pruning, this suggests that microtubule breakdown is required for these plasma membrane alterations. In this scenario, our data actually suggest that microtubule disruption is closely linked to plasma membrane alterations, such that it is interesting to speculate that microtubule loss might trigger local endocytosis and thinning formation during dendrite pruning. Thus, we would like to propose a model where PAR‐1, via Tau and possibly Kat‐60L1, promotes microtubule disruption. In our model, these processes are placed epistatically over plasma membrane alterations during dendrite pruning (Fig 6H).

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks and culture

All crosses were done at 25°C under standard conditions. For expression in c4da neurons, we used ppk‐GAL4 insertions on the second and third chromosomes. GAL4 2‐21 was used to visualize c1da neurons. MARCM clones of par‐1 Δ16 mutants were induced with SOP‐FLP (Matsubara et al, 2011) and labeled by tdtomato expression under nsyb‐GAL4 R57C10. Other fly lines were tau MR22 (Bloomington #9530), EcR 31 (BL #4900) Mov34 k08003 (BL #23860), futsch K68, tau MI03440‐GFSTF (BL #60199), UAS‐GFP::α‐tubulin (BL #7373), UAS‐α‐tubulin–tdEOS (BL #51313, 51314), UAS‐tau::GFP (Rumpf et al, 2011), UAS‐GCaMP6s (BL #42746), UAS‐shi ts (BL #44222), futsch EP1419 (Hummel et al, 2000), UAS‐tdtomato (Han et al, 2014), UAS‐dcr2 (Dietzl et al, 2007), UAS‐PAR‐1 (wild‐type control, isoform RL), and UAS‐PAR‐1KN (kinase domain mutant) (Sun et al, 2001). UAS‐RNAi lines were the following: par‐1 (BL #32410), tau (BL #28891), bazooka (VDRC 2914, NIG 5055R‐1), kat‐60L1 (BL #32506).

Transgenes and cloning

N‐terminally FLAG‐tagged PAR‐1 (isoform RR) and C‐terminally HA‐tagged Drosophila tau (isoform RA) were cloned into pUAST attB. Tau serine 184 was replaced with alanine via PCR. All plasmids were injected into receptive strains carrying attP2 or attP VK37 acceptor sites according to standard protocols.

Dissection, microscopy, and live imaging

Pruning defects were assayed at 18 h APF as described (Rumpf et al, 2014) and analyzed using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope. For PAR‐1 genetic interactions, candidates were crossed to a second chromosome insertion of ppk‐GAL4 combined with UAS‐CD8GFP and UAS‐par‐1RNAi. Here, pupae were analyzed using a Nikon AZ100 dissecting microscope. For GCaMP6s imaging of dendritic Ca2+ transients, pupae were imaged on an inverted Cell Observer SD spinning disk microscope (Zeiss) with a 63× oil immersion objective. Images were obtained with ZEN software (Zeiss) and processed in ImageJ.

Pruning phenotypes were analyzed by counting the number of neurons that still had dendrites attached to the soma, these data were analyzed using a two‐tailed Fisher's exact test. Alternatively, we counted the number of primary and secondary branches still attached to the soma at 18 h APF, or we measured the length of remaining dendrites at that time point. These data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test.

Photoconversion experiments

Photoconversion was carried out according to a previously published protocol (Tao et al, 2016), except that two copies of UAS‐tdEos‐α‐tubulin were expressed under ppk‐GAL4.

Antibodies and immunohistochemistry

Larval or pupal filets were dissected according to standard protocols and fixed in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde. Rabbit, mouse, or chicken anti‐GFP antibodies were from Life technologies or Aves laboratories, respectively, rabbit anti‐DsRed from Clontech, and rat anti‐mcherry from Life technologies. Other antibodies were mouse anti‐acetylated tubulin (Sigma 7451), anti‐polyglutamylated tubulin (Sigma T9822), mAb22C10, mouse anti‐HA F7 (Sigma), guinea pig anti‐Sox14 (Ritter & Beckstead, 2010), rabbit anti‐Ank2XL (Koch et al, 2008), rabbit anti‐PAR‐1 (McDonald et al, 2008).

Recombinant protein expression and phosphorylation assay

Wild‐type or kinase‐dead FLAG‐tagged PAR‐1 (isoform RR) was expressed in S2 cells from pUAST plasmids via coexpression of Act5C‐GAL4. Tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from approx. 3 × 107 cells with anti‐FLAG beads (Sigma) and eluted with 3xFLAG peptide (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The tau ORF was cloned into pGEX6P‐1, and GST‐tau was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 Rosetta and purified with glutathione Sepharose (Pharmacia). An in vitro assay was established according to the method of Allen et al (2007). Briefly, recombinant FLAGPAR‐1 and GST‐tau were incubated in the presence of ATPγS for 30 min at room temperature to allow for phosphorylation, and thiophosphorylated residues were alkylated and detected by Western blot with a specific antibody (Abcam).

Author contributions

SH and SRu designed and conceived the project and interpreted the data. SH, RK, SRo, and SRu performed experiments. SH, SRu, and CK contributed reagents. SH and SRu wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to C. Klämbt for generous support, to C. Klämbt and S. Luschnig for comments on the manuscript, and C. Klämbt, Y. Jan, D. St. Johnston, H. Aberle, J. McDonald, D. Kretzschmar, N. Sherwood, C. Han, and the Bloomington, VDRC, and NIGfly stock centers for reagents and fly stocks. SH is a member of the CiM‐IMPRS graduate school, and S. Rumpf is supported by the DFG Excellence Cluster EXC 1003 “Cells in Motion”.

The EMBO Journal (2017) 36: 1981–1991

References

- Allen JJ, Li M, Brinkworth CS, Paulson JL, Wang D, Hübner A, Chou WH, Davis RJ, Burlingame AL, Messing RO, Katayama CD, Hedrick SM, Shokat KM (2007) A semisynthetic epitope for kinase substrates. Nat Methods 4: 511–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton R, St Johnston D (2003) Drosophila PAR‐1 and 14‐3‐3 inhibit Bazooka/PAR‐3 to establish complementary cortical domains in polarized cells. Cell 115: 691–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernat J, Gustke N, Drewes G, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E (1993) Phosphorylation of Ser262 strongly reduces binding of tau to microtubules: distinction between PHF‐like immunoreactivity and microtubule binding. Neuron 11: 153–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill MS, Kleele T, Ruschkies L, Wang M, Marahori NA, Reuter MS, Hausrat TJ, Weigand E, Fisher M, Ahles A, Engelhardt S, Bishop DL, Kneussel M, Misgeld T (2016) Branch‐specific microtubule destabilization mediates axon branch loss during neuromuscular synapse elimination. Neuron 92: 845–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DN, Lu B, Sun TQ, Williams LT, Jan YN (2001) Drosophila par‐1 is required for oocyte differentiation and microtubule organization. Curr Biol 11: 75–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, Couto A, Marra V, Keleman K, Dickson BJ (2007) A genome‐wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila . Nature 448: 151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerflinger H, Benton R, Shulman JM, St Johnston D (2003) The role of PAR‐1 in regulating the polarised microtubule cytoskeleton in the Drosophila follicular epithelium. Development 130: 3965–3975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewes G, Ebneth A, Preuss U, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E (1997) MARK, a novel family of protein kinases that phosphorylate microtubule‐associated proteins and trigger microtubule disruption. Cell 89: 297–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita SC, Zipursky SL, Benzer S, Ferrús A, Shotwell SL (1982) Monoclonal antibodies against the Drosophila nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci 79: 7929–7933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Song Y, Xiao H, Wang D, Franc NC, Jan LY, Jan Y‐N (2014) Epidermal cells are the primary phagocytes in the fragmentation and clearance of degenerating dendrites in Drosophila . Neuron 81: 544–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Krukkert K, Roos J, Davis G, Klämbt C (2000) Drosophila Futsch/22C10 is a MAP1B‐like protein required for dendritic and axonal development. Neuron 26: 357–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori T, Kanai MI, Dairyo Y, Yasunaga K, Morikawa RK, Emoto K (2013) Compartmentalized calcium transients trigger dendrite pruning in Drosophila sensory neurons. Science 340: 1475–1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori T, Yoshino J, Yasunaga K‐I, Dairyo Y, Emoto K (2015) Local endocytosis triggers dendritic thinning and pruning in Drosophila sensory neurons. Nat Commun 6: 6515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilly D, Gu Y, Huang Y, Wu Z, Bashirullah A, Low BC, Kolodkin AL, Wang H, Yu F (2009) A genetic pathway composed of Sox14 and Mical governs severing of dendrites during pruning. Nat Neurosci 12: 1497–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch I, Schwarz H, Beuchle D, Goellner B, Langegger M, Aberle H (2008) Drosophila ankyrin 2 is required for synaptic stability. Neuron 58: 210–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CT, Jan LY, Jan YN (2005) Dendrite‐specific remodeling of Drosophila sensory neurons requires matrix metalloproteases, ubiquitin‐proteasome, and ecdysone signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 15230–15235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H‐H, Jan LY, Jan Y‐N (2009) Drosophila IKK‐related kinase Ik2 and Katanin p60‐like 1 regulate dendrite pruning of sensory neuron during metamorphosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6363–6368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L (1999) Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron 22: 451–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, O'Leary DDM (2005) Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 127–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maor‐Nof M, Homma N, Raanan C, Nof A, Hirokawa N, Yaron A (2013) Axonal pruning is actively regulated by the microtubule‐destabilizing protein kinesin superfamily protein 2A. Cell Rep 3: 971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara D, Horiuchi S‐Y, Shimono K, Usui T, Uemura T (2011) The seven‐pass transmembrane cadherin Flamingo controls dendritic self‐avoidance via its binding to a LIM domain protein, Espinas, in Drosophila sensory neurons. Genes Dev 25: 1982–1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JA, Khodyakova A, Aranjuez G, Dudley C, Montell DJ (2008) PAR‐1 kinase regulates epithelial detachment and directional protrusion of migrating border cells. Curr Biol 18: 1659–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarkar‐Jaiswal S, Lee PT, Campbell ME, Chen K, Anguiano‐Zarate S, Gutierrez MC, Busby T, Lin WW, He Y, Schulze KL, Booth BW, Evans‐Holm M, Venken KJ, Levis RW, Spradling AC, Hoskins RA, Bellen HJ (2015) A library of MiMICs allows tagging of genes and reversible, spatial and temporal knockdown of proteins in Drosophila . eLife 4: e05338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielage J, Cheng L, Fetter RD, Carlton PM, Sedat JW, Davis GW (2008) A presynaptic giant ankyrin stabilizes the NMJ through regulation of presynaptic microtubules and transsynaptic cell adhesion. Neuron 58: 195–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L, Yu W, Andreadis A, Luo M, Baas PW (2006) Tau protects microtubules in the axon from severing by katanin. J Neurosci 26: 3120–3129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter AR, Beckstead RB (2010) Sox14 is required for transcriptional and developmental responses to 20‐hydroxyecdysone at the onset of Drosophila metamorphosis. Dev Dyn 239: 2685–2694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf S, Bagley JA, Thompson‐Peer KL, Zhu S, Gorczyca D, Beckstead RB, Jan LY, Jan YN (2014) Drosophila Valosin‐Containing Protein is required for dendrite pruning through a regulatory role in mRNA metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 7331–7336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf S, Lee SB, Jan LY, Jan YN (2011) Neuronal remodeling and apoptosis require VCP‐dependent degradation of the apoptosis inhibitor DIAP1. Development 138: 1153–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldiner O, Yaron A (2015) Mechanisms of developmental neurite pruning. Cell Mol Life Sci 72: 101–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Tsubouchi A, Rolls MM, Tracey WD, Sherwood NT (2012) Katanin p60‐like1 promotes microtubule growth and terminal dendrite stability in the larval class IV sensory neurons of Drosophila . J Neurosci 32: 11631–11642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TQ, Lu B, Feng JJ, Reinhard C, Jan YN, Fantl WJ, Williams LT (2001) PAR‐1 is a Dishevelled‐associated kinase and a positive regulator of Wnt signalling. Nat Cell Biol 3: 628–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Feng C, Rolls MM (2016) The microtubule‐severing protein fidgetin acts after dendrite injury to promote their degeneration. J Cell Sci 129: 3274–3281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DW, Truman JW (2005) Cellular mechanisms of dendrite pruning in Drosophila: insights from in vivo time‐lapse of remodeling dendritic arborizing sensory neurons. Development 132: 3631–3642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File