Like an actor in a memorable role, proteins too are typecast by their first prominent function in the cell. Such has been the case with the potent tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) in its widely acclaimed role as a phosphatase. PTEN removes phosphates from specific lipids and from tyrosines on particular proteins, leading to inhibition of growth-promoting signals. Mutations in PTEN, which often inactivate the phosphatase, underlie the pathologic phenotype of common human cancers and inherited syndromes, such as Cowden's disease, Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome, and Proteus syndrome (1). With actors and with proteins, it takes an unexpected and convincing breakthrough to begin to think beyond their marquis role. A report by Okumura et al. (2) in this issue of PNAS showing a functionally important but phosphatase-independent role for PTEN in growth control may help promote that breakthrough.

For nearly every type of protein modification, there is an equal and opposite demodification. Thus, with the discovery of oncogenic kinases, which stimulate cell proliferation by adding phosphate groups to substrates, it was speculated that, because phosphatases could counteract kinases, they might act as tumor suppressors. The decade-long dearth of evidence to support this speculation sets up a dramatic entrance for PTEN, ushered in independently by two groups showing that PTEN was frequently mutated in human tumors and that PTEN showed sequence similarities to tyrosine phosphatases. Initial studies indeed confirmed that PTEN displayed tyrosine phosphatase activity, albeit very weakly against the substrates tested (3), but a seminal report from Maehama and Dixon (4) demonstrated that PTEN was very effective at dephosphorylating phospholipids, specifically those phosphorylated by the oncogene phosphati-dylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase). Furnari, Huang, and Cavenee (5) confirmed the phosphatase activity and showed that wild-type PTEN suppressed the growth of human tumor cells. A crucial experiment in Furnari et al. (5) showed that the protein and lipid phosphatase activities could be separated and that the growth inhibition was significantly reduced in the absence of functional lipid phosphatase activity. Myriad publications since have firmly established a central role in growth suppression for the lipid phosphatase domain of PTEN. This phosphatase-centered view, although certainly warranted, may have slowed speculation about the other end of PTEN, which was thought to be primarily structural until recently.

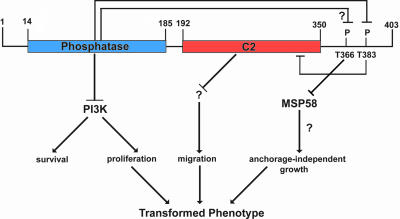

The phosphatase domain of PTEN spans the N-terminal half of this protein. The remainder consists of a domain that shows a protein fold reminiscent of a C2 domain (6), followed by a C-terminal tail consisting of several phosphorylation sites and terminating in a 3-aa PDZ domain-binding motif. To elucidate functions of PTEN that might be independent of its phosphatase domain, Furnari, Cavenee, and coworkers (2) performed a screen for proteins that would interact with the C-terminal half of PTEN. One of the proteins they isolated was a relatively obscure nuclear protein termed microspherule protein 58 (MSP58). MSP58 has binding partners other than PTEN, including the proliferation-related nucleolar protein p120 and the transcriptional repressor Daxx. MSP58 has previously been implicated in cell transformation because its avian orthologue induces transformation and its expression is induced by v-Jun (7). MSP58 has a domain that binds specifically to phosphorylated proteins; therefore, Furnari, Cavenee, and coworkers (2) tested whether the interaction with PTEN was through one of its phosphorylated residues in its “tail,” which was indeed the case, and mutation of a single phosphorylation site Thr-366 completely abolished its association with MSP58.

Under some conditions the suppression of transformation by PTEN is independent of phosphatase activity.

This finding raises the critical question of whether the interaction with PTEN has any effect on the ability of MSP58 to transform cells. If so, MSP58 might then ride to the forefront of cancer biology on the C-terminal tail of PTEN while also signifying a potentially new role for this C-terminal portion in preventing transformation. In a well controlled experiment with mouse cells that lack the PTEN gene, expression of MSP58 caused transformation as it had in avian cells, but, when Okumura et al. (2) coexpressed wild-type PTEN, transformation was abolished. It remained formally possible that this effect relied on the phosphatase domain as has been proven for nearly all other PTEN-mediated cellular effects. However, coexpression of a form of PTEN that does not possess phosphatase activity also abolished transformation, showing that in this setting the suppression of transformation by PTEN is independent of phosphatase activity. In contrast, a form of PTEN that cannot physically interact with MSP58 because of the mutation of Thr-366 was unable to suppress transformation. This phosphatase-independent role for PTEN raises many more important questions about the relative levels of MSP58 and PTEN in human tumors and the consequence of the PTEN mutations found within the C-terminal domain.

Several additional clues of an important role for PTEN independent of its lipid phosphatase activity have emerged recently. Although the phosphatase domain is the predominant target for mutations in human tumors, there exist mutations outside this region in its C2 domain. Indeed, mutations in this region were shown to reduce the ability of PTEN to suppress growth while not affecting its activity to dephosphorylate lipids (6). There have also been reports that the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN may have roles independent of its lipid phosphatase domain. Inhibition of cell migration and invasion was observed upon expression of a form of PTEN that could only dephosphorylate protein substrates (8). This same mutant form of PTEN could also cause cell cycle arrest when expressed in human breast cancer cells (9). If the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN is important for some of its functions, the question emerges, What are its substrates? A surprising result from Hall and colleagues (10) suggests that the answer could be PTEN itself. Raftopoulou et al. (10) show that the inhibition of cell migration by PTEN requires its protein phosphatase domain to dephosphorylate a specific residue in its C-terminal tail, namely Thr-383 (Fig. 1). When Thr-388 was mutated to alanine to prevent phosphorylation, full-length PTEN or just the isolated C terminus was effective in suppressing cell migration (10). A further phosphatase-independent role for PTEN was identified by Freeman et al. (11), who showed interaction with and stabilization of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by a catalytically inactive form of PTEN. Interestingly, it was also the C2 domain of PTEN that mediated this interaction (11).

Fig. 1.

Phosphatase-dependent and phosphatase-independent roles for PTEN in growth suppression. An established role for PTEN is the inhibition of PI3-kinase function by dephosphorylating its phospholipids products. Raftopoulou et al. (10) showed that the inhibition of cell migration by PTEN requires its protein phosphatase domain to dephosphorylate a specific residue in its C-terminal tail, namely Thr-383. Okumura et al. (2) now show that the C-terminal portion of PTEN also has a role in growth suppression, by virtue of its ability to inhibit MSP58-mediated cellular transformation. Inhibition of MSP58-mediated transformation does not require the phosphatase activity of PTEN. Thr-366 of PTEN is within the MSP58 interaction domain and is critical for inhibition of transformation. Questions to be addressed include whether PTEN itself might dephosphorylate Thr-366 in addition to Thr-383 and which pathway mediates MSP58-induced, anchorage-independent growth.

Clearly, PTEN has now broken free of its typecasting as a one-role tumor suppressor. However, many questions still remain. Does the protein phosphatase of PTEN act on Thr-366 in regulating its interaction with MSP58? Is MSP58 an important target in mediating the inhibition of cell migration by PTEN? Is MSP58 representative of a larger group of proteins whose activities are regulated by physical association with PTEN? The data of Okumura et al. (2) showing the existence of a PTEN phosphatase-independent suppression of transformation and the convergence of two unexpected cancer pathways, one prominent and one obscure, will certainly expand the scope of PTEN research. Perhaps the findings will even stimulate the reevaluation of past results, such as the rather puzzling nuclear localization of PTEN (12). In addition, the assumption that the growth of PTEN mutant tumors would be curbed by PI3-kinase inhibitors should now also consider the data provided by Okumura et al. (2). Only time will tell how important this role for PTEN, and the path to prominence for MSP58, will become for cancer biology and therapeutics.

See companion article on page 2703.

References

- 1.Eng, C. (2003) Hum. Mutat. 22, 183–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okumura, K., Zhao, M., DePinho, R. A., Furnari, F. B. & Cavenee, W. K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2703–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers, M. P., Stolarov, J. P., Eno, C., Li, J., Wang, S. I., Wigler, M. H., Parsons, R. & Tonks, N. K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94, 9052–9057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maehama, T. & Dixon, J. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13375–13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furnari, F. B., Huang, H. J. & Cavenee, W. K. (1998) Cancer Res. 58, 5002–5008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee, J. O., Yang, H., Georgescu, M.-M., Di Christofano, A., Maehama, T., Shi, Y., Dixon, J. E., Pandolfi, P. & Pavletich, N. P. (1999) Cell 99, 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bader, A. G., Schneider, M. L., Bister, K. & Hartl, M. (2001) Oncogene 20, 7524–7535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamura, M., Gu, J., Takino, T. & Yamada, K. M. (1999) Cancer Res. 59, 442–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hlobilkova, A., Guldberg, P., Thullberg, M., Zeuthen, J., Lukas, J. & Bartek, J. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 256, 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raftopoulou, M., Etienne-Manneville, S., Self, A., Nicholls, S. & Hall, A. (2004) Science 303, 1179–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman, D. J., Li, A. G., Wei, G., Li, H. H., Kertesz, N., Lesche, R., Whale, A. D., Martinez-Diaz, H., Rozengurt, N., Cardiff, R. D., et al. (2003) Cancer Cell 3, 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiteman, D. C., Zhou, X. P., Cummings, M. C., Pavey, S., Hayward, N. K. & Eng, C. (2002) Int. J. Cancer 99, 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]