Abstract

Efforts to engage consumers in the use of public reports on health care provider performance have met with limited success. Fostering greater engagement will require new approaches that provide consumers with relevant content at the time and in the context they need to make a decision of consequence. To this end, we identify three key factors influencing consumer engagement and show how they manifest in different ways and combinations for four particular choice contexts that appear to offer realistic opportunities for engagement. We analyze how these engagement factors play out differently in each choice context and suggest specific strategies that sponsors of public reports can use in each context. Cross-cutting lessons for report sponsors and policy makers include new media strategies such as a commitment to adaptive web-based reporting, new metrics with richer emotional content, and the use of navigators or advocates to assist consumers with interpreting reports.

Keywords: consumer engagement, public reporting, health care quality, medical consumerism

Introduction

Public reporting on the performance of health care providers has become increasingly common in the United States (Christianson, Volmar, Alexander, & Scanlon, 2010). While reports vary considerably in their content and focus, most sponsors indicate that a primary objective is to inform consumer choice of providers (O’Neil, Schurrer, & Simon, 2010). Despite this explicit aim, evidence that consumers are actually using these reports is mixed, at best (Fung, Lim, Mattke, Damberg, & Shekelle, 2008). According to a 2008 national poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 30% of Americans said they had seen information in the past year comparing the quality of different health insurance plans, hospitals, or doctors, but only 14% said they had used the information (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2008). The share of respondents that had seen and used information comparing the quality of doctors was only 6%.

In this article, we suggest that low levels of consumer awareness and use of public reports have resulted at least in part because most reports have failed to deliver relevant information at the time and in the form appropriate to the context in which consumers actually make choices among health care providers. We argue that fostering greater consumer engagement with public reports will require finding ways to deliver context-specific information to people who are motivated to use it, at the time they need it, and in a form that suits the context for choice. Understanding and targeting the most common decision situations in which consumers need to choose a provider is a key to developing effective ways to engage consumers with public reports.

We examine four specific decision contexts and discuss how consumer engagement and receptivity to information in each situation are likely to be affected by a set of three engagement factors that are common to all health care choices: (a) an individual’s emotional state in the choice situation, (b) consumers’ capacity to interpret multiple measures of performance, and (c) consumers’ need for trusted sources of support to help interpret complex information. Our analysis and recommendations are focused on finding commonalities in consumer attitudes and behavior in circumstances that might otherwise appear dissimilar, so that public reporting can be improved by addressing a set of common leverage points for enhancing consumer engagement.

Each of the decision contexts we examine involves a wide range of consumers and experiences, but it is precisely because of this heterogeneity that we believe it is crucial to identify common factors influencing engagement for successful context-based reporting strategies. Furthermore, because each of these common factors manifests differently as it interacts with the other factors in each context, the way that each factor influences consumer engagement will also differ across contexts. The practical implication of these differing effects for report sponsors is that each context will require customized strategies for leveraging the factors of engagement. By suggesting an approach to engaging consumers that is adapted to their varied circumstances and that begins by meeting the needs of different subsets of consumers, each on their own terms, our analysis provides direction for specific practical implications for report developers, as well as for future research and policy development.

New Contribution

While the notion that context and timing are important to engagement is not new, these dimensions of public reporting have received far less attention among researchers and report developers than have issues of report format design and presentation (Shaller et al., 2003). The idea that there are certain “decision points” when people are receptive to information about local health care providers has been advanced in research conducted from a communications and marketing perspective for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Aligning Forces for Quality, 2010). But this idea has received relatively little attention in the peer-reviewed literature discussing the challenges of public reporting (Marshall, Romano, & Davies, 2004; Marshall, Shekelle, Davies, & Smith, 2003; Sinaiko, Eastman, & Rosenthal, 2012). Even when researchers are aware of these market niches, they rarely consider how public reporting might be misinterpreted or lead to suboptimal choices if not properly attuned to the information needs of particular subsets of consumers.

Some circumstances that induce consumers to choose a health care provider emerge from threats to their health and well-being. For example, consumers’ need to deal with a chronic illness or undergo diagnostic testing detecting serious diseases can be a powerful motivator to seek out the best health care professionals. In these circumstances, attending to and acting on provider performance information can be regarded as protective health behavior. Considerable research has been done on people’s adaptive and maladaptive coping responses to health threats (e.g., Milne, Sheeran, & Orbell, 2000; Rippetoe & Rogers 1987; Ruiter, Abraham, & Kok, 2007; Witte & Allen, 2000;). Findings from this literature highlight the role that emotions may play in how people in difficult circumstances respond to information, sometimes finding it more comforting to ignore it entirely. To date, little attention has been paid to the implications of this research for anticipating consumer response to public reports on provider quality.

The literature on market niches for health care consumers and the literature on health threats activating medical consumerism have developed in isolation from one another. Part of the contribution of this article is to identify conceptual threads that connect them together—and that reveal common factors in a strategy for enhancing consumer engagement with public reports across these distinct circumstances.

How Context Matters

We use context as a shorthand way of describing the circumstances that help motivate consumers to choose a health care provider and that influence the way they go about doing so. These circumstances place consumers “in the market” for a health care provider, a state that they are not likely to be in most of the time, thereby making information relevant to choosing a provider salient in a way that it would not be otherwise. Consumers pay much more attention to information about products or services when they perceive the information as relevant to an imminent purchase decision (Celsi & Olson, 1988; Pratkanis & Greenwald, 1993).

Because people pay little attention to matters that do not seem pressing, information contained in public reports about health care performance will typically be ignored by most people, most of the time. To promote engagement, it is therefore necessary to identify circumstances when this sort of information might be more salient—and then to examine how information is interpreted and used in these contexts.

To illustrate the potential of context to help leverage consumer engagement, we examine four specific decision situations:

People shopping for short-term treatments

People encountering some form of external disruption prompting the need to choose a new provider

People with serious chronic conditions

People experiencing problems with their current health care provider.

These examples clearly do not exhaust every possible context; nor do they illustrate every motivation for or barrier to seeking out and using health care performance reports. However, they do represent some of the most common and consequential contexts, each affecting a substantial portion of the public every year. Moreover, they provide opportunities for suggesting specific ways that report developers can leverage particular decision-making contexts to influence consumer engagement.

Circumstances in each of these contexts motivate consumers to seek out information about health care providers. But the distinctive features of each context will affect the sort of information that seems most salient, how that information affects consumers’ perceptions, choices and actions, as well as how much effort consumers are willing or able to give to make sense of comparative quality metrics or cost data.

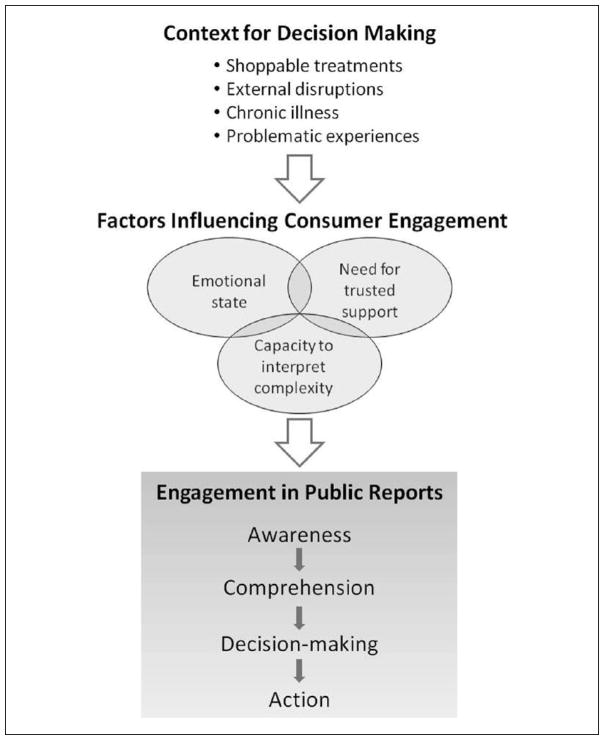

Factors Shaping Consumer Engagement

To systematically explore how context shapes engagement, our analysis is framed in terms of three factors that the literature has shown to powerfully and consistently shape how consumers seek out information and try to make sense of performance measures. We aim to demonstrate how the interaction of these three factors in each context leads to a distinct set of implications for consumer engagement, requiring a distinctive response by report sponsors in order to enhance engagement. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model illustrating the relationship between the context for decision making, the factors influencing engagement, and the interaction and influence of these factors on consumers’ engagement in public reports. Table 1 builds on this conceptual model by presenting a summary of our analysis with specific examples of how engagement can be promoted in each of the four decision-making contexts we examine.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for context-based reporting strategies.

Table 1.

Examples of Strategies for Promoting Consumer Engagement in Specific Decision-Making Contexts.

| Factors influencing consumer engagement | Contexts for consumer decision making

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoppable treatments | External disruptions | Chronic conditions | Problematic experiences | |

| Emotional state of consumers | ||||

| Potential for engagement | Limited engagement; seeking positive emotional connection with providers | Low-grade anxiety; potential frustration | Chronic anxiety; compensatory coping | Severe distress: evoking anger and/or anxiety |

| Strategies for promoting engagement | Facilitate engagement with reports richer in emotional content | Incorporate measures of emotional connectedness with primary care | Facilitate sense of coping; enhance sense of comfort and self-efficacy | Reduce anxiety that induces information avoidance |

| Consumers’ capacity to interpret complexity | ||||

| Potential for engagement | One-off event; balancing costs and quality | Time-sensitive; need to restore disrupted relationships | Can build sense of understanding and connections over time | Urgent; other metrics for “bad outcomes” become most salient |

| Strategies for promoting engagement | Need to provide support for integrating cost and quality metrics | Emphasis on communications and coordination | Staged levels of information to develop expertise gradually | Sequencing of metrics to emphasize bad outcomes (e.g., complaints, errors) |

| Consumers’ need for trusted support | ||||

| Potential for engagement | Shoppable conditions often limit need for trust | Loss of trusted advisors | Importance of maintaining trusted relationships | Loss of trust in advisors |

| Strategies for promoting engagement | Make the case that the data will help the consumer get better outcomes or value | Provide access to a trustworthy navigator | Consumerism more likely to take the form of voice than choice | Provide access to a trustworthy advocate |

Consumers’ Emotional State

The first factor of engagement involves consumers’ emotional state when they are making choices. Some medical contexts hold the promise of “being made better” in a variety of ways—evoking a positive set of anticipations and emotions—though others carry with them anxiety, or even dread. People gripped by these emotions will resonate with some forms of information while other forms may feel more distant or even aversive (Vohs, Baumeister, & Loewenstein, 2007). In Table 1, our four decision contexts have been arrayed along a continuum ranging from settings likely to evoke a mix of positive and negative feelings for consumers to those likely to involve circumstances filled with pervasive and lasting anxiety.

Consumers’ Capacity to Interpret Complexity

The second engagement factor involves consumers’ capacity to make sense of multiple measures of performance. Even when consumers are motivated to learn, the complexity of medical decision making may seem overwhelming for many of them. This is particularly true as public reports incorporate more measures of quality, cost, or other attributes of provider practices (Schlesinger, Kanouse, Rybowski, Martino, & Shaller, 2012). Under these circumstances, consumers will often focus on a smaller subset that seems most relevant to their choices and well-being. Past research suggests that this selective attention is strongly shaped by consumers’ past personal experiences in health care settings, which render some attributes of medical care more salient than others (Armstrong et al., 2009). As shown in Table 1, since these experiences are very different across our four illustrative contexts, so too are the types of performance metrics to which consumers can be expected to be most attentive.

Consumers’ Need for Trusted Support

A third factor consistently influencing medical consumerism involves the need for external sources to which people can turn for trusted advice in making sense of their health care experiences. Interpretive assistance often plays a crucial mediating role in consumer engagement (Carman et al., 2013). Trusted sources can include family members, primary care clinicians, coworkers, or human resource managers at work, or others who share the same chronic conditions, contacted individually or in support groups. The degree to which an individual is likely to need (and have available) trusted sources of advice will vary across the four contexts summarized in Table 1. The roles for trusted advisors will also be affected by the previous two factors related to consumers’ emotional state and capacity to interpret complex information.

In each context, these three factors all interact with one another. For researchers, understanding this interaction is crucial for assessing the hindrances to effective consumer engagement and identifying various ways to enhance that engagement. But these interactions are complex. For public report sponsors, whose job it is to find a reporting strategy that will engage a specific audience in a specific context, the most important takeaway from these complex interactions is the understanding that a successful report needs to capture the audience’s attention, provide information the audience views as relevant and trustworthy, and offer to help them reach goals they care about. There are various approaches to achieving these things, and the best approach to use will vary across contexts. Finding the best approach requires testing prospective displays and text with consumers who represent the perspective of the intended audience (Kanouse, Spranca, & Vaiana, 2004; McGee et al., 1999). This can include consumers who have recently experienced the context of interest as well as consumers who are currently experiencing it. The research literature on health communication, resources such as Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Talking Quality website (https://talkingquality.ahrq.gov/), and articles such as this one can elucidate what the goals should be and suggest approaches that are worth testing. However, success ultimately depends on how the intended audience actually responds to the report.

Four Choice Contexts for Promoting Engagement

Shoppable Treatments

Relatively healthy people who have brief encounters with health care comprise a substantial audience for public reports on comparative quality. Examples of such encounters include elective procedures, such as joint replacement or preventive screenings such as colonoscopy, Lasik and cosmetic surgery, and maternity care. Tens of millions of Americans encounter medical care exclusively through these time-limited episodes each year (National Hospital Discharge Survey, 2010). Because these elective treatments can be planned in advance and often allow choice among many providers, they constitute highly “shoppable” events.

Factors Related to Engagement

People contemplating or having resolved to undergo an elective procedure may be motivated to seek out information on both the quality and cost of alternative providers, since past research shows that use of these treatments is relatively cost-sensitive. By contrast, the role of personal experience is likely to be highly dependent on the nature of the treatment. Frequent users of cosmetic surgery or women who have had multiple births may feel very confident about their previous choices or secure enough with the experience to know what they are looking for in alternatives. However, many elective procedures may simply be “one-off” episodes with no prior experience needed to prompt information seeking for the best value. Consumers who contemplate “one-off” elective procedures may have little idea about how much quality varies among providers or about the metrics that are available to help them choose wisely.

The emotional stakes involved in short-term episodes depend to a great extent on the nature of the elective treatment. Preventive procedures, such as colonoscopy undertaken for screening in the absence of symptoms are likely to have a low level of emotional investment. In contrast, first-time or high-risk pregnancies may engender significant anxiety over finding a high-quality provider. In a more positive vein, maternity care for a normal delivery may evoke feelings of joy that might motivate a search for just the right childbirth environment and related amenities.

Implications for Engagement Strategies

The “shoppable” nature of many short-term treatment episodes suggests the value of turning to successful engagement strategies for supporting consumer shopping in other sectors. A study sponsored by the Center for Advancing Health examined several popular consumer guides outside the health care sector for insights and lessons to improve the development and dissemination of health care decision tools, such as public reports on quality (Center for Advancing Health, 2009). In reviewing the success of such well-known decision support tools as Consumer Reports’ Car Buying Guide, U.S. News and World Report’s College Guide, and eBay, the study identified several key lessons that are relevant for engaging consumers in using public reports on health care providers. These include the importance of

Getting the right tool to the right audience at the right time, which involves closely aligning the content and functions of the decision aid with the needs and interests of the target audience

Establishing a high degree of trust in the independence and competence of the tool sponsor, often through the creation of strong brand identities

Using systematic and sustained marketing, promotion, and dissemination that can reach consumers not yet connected with the health care system.

These lessons are useful in developing reports for a range of contexts, not just when consumers are shopping for treatments where there are many available options and time to make a decision. However, shoppable treatments provide the choice context that most closely resembles the situation consumers face when purchasing goods or services in a competitive marketplace, so that the lessons learned from successful efforts to engage consumers with guides outside of health care are especially relevant. Moreover, for many shoppable treatments, consumers search for needed information at a distance (literally and emotionally) from the health care providers under consideration, requiring outreach strategies to consumers who have little experience with medical care and in settings that lack other sources of information about treatments.

A useful example applying these lessons involves the California HealthCare Foundation’s online marketing campaign focused on promoting use of the CalHospitalCompare.org public reporting website. The Foundation focused on the “shoppable” condition of maternity care, using targeted ads to encourage pregnant women in three California media markets to use the CalHospitalCompare.org ratings for local hospitals (California HealthCare Foundation, 2009). These efforts resulted in a significant increase in website traffic, including an 11-fold increase in visits to the websites of the target market hospitals. This successful example illustrates the importance of promoting health care information based on the needs and interests of the target audience.

Although this context represents a promising setting for enhanced consumer engagement, it poses some distinct challenges as well. Because so many consumers encounter these choices as one-off events, they will have had limited experience making sense of the relevant quality metrics. And since many will have no particular reason to think that quality varies substantially among providers, they may have little motivation to pay attention to quality metrics. They will likely view existing measures with less interest, understanding, or trust than will more “experienced consumers” (Schlesinger et al., 2012). Effective engagement will depend on strategies to make a case for the relevance of quality information and to offset or overcome that distrust. Strategies for gaining trust include explaining why the organizational sponsor is providing the information (e.g., as a public service, or to help consumers make informed choices), describing methods used in gathering the data to minimize bias and prevent the providers whose quality is being evaluated from gaming the evaluation, and labeling and explaining the quality measures in ways that consumers find understandable.

External Disruptions

People moving to a new area, changing jobs, or changing health plans often need information on selecting a new health care provider. According to the 2007 Household Survey conducted by the Center for Studying Health System Change, just more than 10% of Americans reported looking for a new primary care provider in the previous 12 months, and almost 30% reported needing a new specialist (Tu & Lauer, 2008). These disruptive external circumstances frequently create favorable situations for engaging consumers in the use of public reports, but also pose certain challenges.

Factors Related to Engagement

In general, people who need to find a new provider because of disruptive circumstances will be at least mildly motivated to seek out information sources. In some cases, people will have a short window in which to make a choice, such as during open enrollment or a move to a new location. Time-limited situations for making a choice require making timely information available to support decision making.

The experience people will bring to a disruptive situation requiring the choice of a new provider will vary greatly depending on the situation. For many employees, open enrollment season for changing plans may be a routine annual event. On the other hand, moving to a new location or changing jobs may be relatively rare.

Disruptive circumstances may contribute to an unsettled emotional state. The loss of a long, established relationship with a personal physician may create anxiety about finding a suitable replacement. In general, disruptive circumstances will likely raise the emotional stakes of making choices about replacement or substitution.

But perhaps most consequentially, disrupted circumstances can leave consumers without much trusted support for making health care choices. This disruption will be most pronounced when households move to a new locale while changing jobs. With new coworkers and employer, it may be difficult to discern whom to trust for advice on medical matters. In a new place, one cannot count on referrals from one’s previous clinicians. Under these circumstances, consumers may well feel lost—and potentially overwhelmed by the task of making sense of their choices all on their own.

Implications for Engagement Strategies

The time-sensitive nature of this choice context suggests the need for highly responsive information sources to provide easily accessible, just-in-time information. Emotional anxiety raises the importance of trust in information sources, but the question remains—who can be trusted to provide reliable information?

One approach to addressing these issues can be found in the State of Minnesota’s public employee insurance program. State employees are required to choose a primary care clinic each year during open enrollment. An online clinic directory enables the employee to search for clinics by name, location, health plan affiliation, and cost level (Minnesota Management & Budget, 2012). For most clinics, a direct link is provided to comparative quality information on the Minnesota Health Scores site maintained by Minnesota Community Measurement, a multi-stakeholder Chartered Value Exchange program (Minnesota Community Measurement, 2012a). Thus, employees are able to obtain the information they need (including comparative quality reports) when they need it, from a trusted source (their employer having established an effective track record for supporting consumer choice in health care settings).

Because most consumers shopping for a new primary care provider have limited motivation and face a limited decision “window” for choice, they often respond well to performance reports that incorporate roll-up measures that consolidate results from more specific measures of clinician performance. When provided information in this format, most will lack the motivation to probe down to the component measures, even if they have complete freedom to do so (Schlesinger et al., 2012). Consequently, facilitating choice for this group may come at the cost of reduced exposure to the breadth of relevant measures of clinician quality; enhanced consumer engagement may come at the cost of reduced consumer education.

However, it may also be helpful to consider other arrangements for assisting with choice, especially for households that have moved to a new and unfamiliar locale. Or for those who work for smaller employers or in less stable employment—and therefore are unable to turn to their workplace as a source of trusted advice. Learning how to find their way through an unfamiliar health care system might be greatly facilitated if consumers had recourse to the sort of “navigator” envisioned to assist consumers in the new health insurance exchanges created under health care reform in the United States (Day & Nadash, 2012). These navigators are meant to serve largely as interpretive guides, providing objective and unbiased information about the choices available to the consumer.

Serious Chronic Conditions

Roughly 125 million Americans live with one or more chronic conditions (Anderson & Horvath, 2004). People with chronic diseases often have a continuing need to know about how best to manage their health condition in order to avoid complications or deterioration, minimize symptoms, and improve their health. Management strategies typically require monitoring and are only partially successful in reducing or eliminating symptoms. For that reason, many people with chronic conditions periodically scan the environment for information about their condition and its management.

Factors Related to Engagement

People with chronic conditions are especially likely to be motivated to learn about their condition so that they understand what it means for their health, so they can explain it to family and friends, and so they can manage it and/or discuss it with their physician. Information about best practices or reports about alternative approaches that have worked well for others may also lead a person with a chronic condition to consider making a change of provider. However, if their relationship with their current provider has been a satisfactory one, they may be more likely to discuss new approaches with their current provider first, exercising voice before choice.

Initial diagnosis is likely to be a time in which interest in such information is especially strong, but it may also be accompanied by intensely emotional states. Strong emotional reactions can impede the ability to process information in the short term and make the individual more likely to engage in denial or avoidance rather than positive coping strategies. By contrast, if the patient sees the chronic condition as a continuing challenge whose management requires ongoing assessment and occasional revision or adjustment, interest in new information about the condition and its management may persist at a high level.

Sustained contact with the health care system raises the odds that patients will experience problems, such as medical errors or poorly organized care. Because many patients with chronic conditions see multiple providers, they are likely to have experiences that make them much more aware than most patients that providers vary both in the technical quality of the care they provide and that coordination of care often breaks down in the face of complex medical needs.

Implications for Engagement Strategies

Because serious chronic illness is likely to evoke intense negative emotion and high perceived threat, it is important for health communications to provide positive efficacy messages that emphasize the person’s ability to take actions that control the danger to health. High perceived threat tends to lead to defensive avoidance when perceived efficacy is low, but to adaptive danger control behaviors when perceived efficacy is high (Witte & Allen, 2000).

People with serious chronic conditions often have a strong motivation to learn effective coping strategies for managing their illness, including finding a health care provider who provides care that is consistent with current recommended guidelines and supports their own aspirations for self-care. Diabetes provides a clear example of a serious condition that requires a high degree of patient engagement for successful management. Many patients with this condition are highly knowledgeable about this disease, what they need to do to control it, and what their provider should be doing as well (Aligning Forces for Quality, 2010). Efforts to promote effective patient–provider partnerships in disease management, such as Minnesota Community Measurement’s “D5” program (Minnesota Community Measurement, 2012b) and the Cincinnati Chartered Value Exchange’s “Your Health Matters” website (Your Health Matters, 2012), provide a natural venue for informing motivated patients about how well clinics in their community are meeting therapeutic goals for a specific patient population. Other venues for reaching populations with chronic diseases include consumer groups that advocate for or support people with specific chronic conditions. These groups can both enhance access to information and provide a vital role in interpreting performance metrics. Often they are quite willing to work with sponsors to help develop user-friendly reports and to advise or assist in disseminating them.

Consumers with chronic conditions are more likely to judge standardized performance metrics as trustworthy and reliable (Schlesinger et al., 2012), presumably because their extensive exposure to medical settings enables them to perceive that these metrics capture important aspects of care and gives them a context to help interpret these scores. But conditions that are more serious and debilitating may render it harder for consumers to attend to the complexities of provider choice—indeed, may place such a high premium on maintaining continuity of care with existing providers that consumers are reluctant to even think about alternative venues for care (Schlesinger, Druss, & Thomas, 1999). Under these circumstances, it may be more effective to frame performance information as a means of evaluating the care one is receiving from current providers and working with them to address shortfalls, rather than seeking better quality elsewhere.

Problematic Medical Experiences

Most Americans deeply trust their health care providers (Goold & Klipp, 2002; Hall, Dugan, Zheng, & Mishra, 2001), even when they suspect that most other doctors are incompetent or overly concerned with their financial bottom line (Jacobs & Shapiro, 1994; Miller & Horowitz, 2000). These favorable preconceptions limit patients’ motivations to seek out report cards for medical providers or to pay much attention to performance metrics, should they encounter them.

But expectations can change when problems emerge in the accessibility or quality of their medical care (Mechanic & Meyer 2000; Nelson & Larson 1993). Such catalytic changes are not uncommon; based on surveys of patient experience, roughly a third of all Americans report problems with either quality of care or access to care in the past year (Mitchell & Schlesinger, 2005; Schlesinger 2011; Schlesinger, Mitchell, & Elbel, 2002). Nearly 8% of the public (17.5% of those who reported a problematic experience) had switched doctors in the past year in response to some problem.

Factors Related to Engagement

When patients’ experiences deviate from their generally optimistic expectations, most seek to understand what befell them. This quest to make sense of their experiences is motivated by the need to determine if their experiences were avoidable, who might be to blame for errors or misjudgments, or to seek recompense (often simply an apology) from culpable parties and reduce the risks that problems will reoccur (May & Stengel, 1990; Rosenthal & Schlesinger, 2002; Wofford et al., 2004). Since these stakes are high, patients’ motivation to learn will often be quite strong; they can be expected to actively search from a variety of sources of information, including performance reports.

In the aftermath of perceived problems or errors in medical care, patients will naturally become more cautious than before. This sensitizes them to iatrogenic risks, so they will find most salient performance measures that can reduce the odds of repeating bad experiences, including competence measures such as the prevalence of “never events” or the number of complaints, lawsuits, or other forms of patient grievances, rather than measures keyed to best practices.

Having one’s health decline, even with the best of medical care, is inevitably upsetting. Experiencing medical errors, misjudgments, or other malfeasance raises the emotional stakes even higher—particularly if providers were previously seen as trustworthy. What this implies for patient engagement depends on both the form and the intensity of this emotional response.

Unexpected threats (or disrupted trust) can evoke fear, anger, or some combination of the two (Tiedens & Linton, 2001). Anger is more likely when the events causing the problem could plausibly have been avoided, making the risks actionable and the potential for their remediation real. Fear is more often induced when causes are vague or unknown, making comparable problems seem just as likely in the future. As a result, when the predominant emotion is anger, motivation is high to reduce future risks and patients can be expected to seek out information toward this end.

By contrast, when fear is the primary emotion induced by health care experiences, expectations regarding information seeking are likely to be far more complicated. Modest levels of anxiety encourage patients to pay greater attention to quality, rather than simply assume that all providers are equally competent (Gray & Ropeik, 2002). But more intense anxiety may induce the opposite response: people who are extremely anxious actively avoid information about risk, even if freely available. This emotional logic yields some ironic consequences: information avoidance is most pronounced among individuals who face the greatest personal risks (Kőszegi, 2003; Witte & Allen, 2000). And it produces some very complex patterns of consumer behavior—it is not enough to assess whether consumers’ past experiences have made them anxious about their future care, since moderate anxiety may induce greater engagement whereas extreme anxiety leads to information avoidance. It is essential to have more nuanced arrangements that can be attentive to consumers’ emotional state, in all of its complexities.

Implications for Engagement Strategies

Taking into account the impact of problem-induced information seeking by medical consumers raises three sets of considerations. The first involves potential biases in making use of diverse performance metrics. Because patients who have experienced problems will be predisposed to favor measures of bad performance, making it possible for consumers to view the lower as well as the upper tail of performance measures (or alternatively, providing the entire distribution of responses) may render these metrics more salient and thus more frequently used.

A second consideration involves the potential for information avoidance. Patients with limited education, those with little social support to help them make sense of their medical circumstances, and those who are extremely anxious can all be expected to avoid performance reports, even if they are made freely available. There may need to be more active forms of outreach to overcome this avoidance.

Finally, because problem attribution in medical settings is so challenging, patients in these contexts would benefit from the involvement of a medical advocate who can help them make sense of their circumstances and discern how performance reports can guide their future choices. This sort of external assistance would prove particularly valuable for consumers whose experiences have left them with a crisis of confidence regarding health care providers—they would greatly benefit from a trustworthy source who can help them cope with their anxieties while also working with them on appropriate responses to their problems. Some people, of course, will be able to turn to family members, friends, or others in their social networks. But for consumers who are more isolated, it may be important to offer access to a trusted third party who can help them interpret performance ratings and make sense of their provider options.

To aid report sponsors in making such assistance available, several useful lessons can be drawn from the implementation of consumer assistance programs under health care reform (Grob, Schlesinger, Davis, Cohen, & Lapps, 2013). To help Americans deal with insurance problems, insurers are required to notify their enrollees of the existence of the consumer assistance programs whenever they deny coverage for benefits. Similarly, one might envision a system of notification that would be triggered when patients experienced problematic health outcomes of various sorts, letting them know about the availability of patient advocates who could help them cope with their future medical choices.

Practical Implications for Report Developers

Several cross-cutting implications for report developers emerge from our analysis of these four choice contexts and the role of the three engagement factors common to each.

Identify a Target Audience for Decision Making

A key strategy for promoting consumer engagement with public reports is to identify and target consumers who are “in the market” to make a decision about choosing among health care providers. The four decision-making contexts examined in this article illustrate some of the most prevalent in which consumers may be receptive to comparative performance information. A common attribute of these choice contexts is the role of transitional states. People tend to consider their options and become receptive to information in times of transition. Changing circumstances can focus consumers’ attention on health care choices. Report developers may therefore want to consider such transitional triggers in identifying specific target audiences. When consumers are not in these receptive states, reporting arrangements should focus instead on cultivating skills related to information acquisition that can be used by consumers at a later date when they are more relevant, and providing consumers with easy-to-follow instructions on how they can find such information when they need it.

Once target audiences have been identified, it is necessary to provide them with relevant information at a time they are likely to use it. This often requires customizing the content—for example, designing a report for people contemplating hip replacement surgery that provides quality and cost measures specifically for that surgery rather than a broad array of measures that span many surgical and nonsurgical treatments. Targeted dissemination strategies may also be necessary, using marketing and promotion or disseminating reports in partnership with groups or organizations whose mission it is to help those in the target audience.

Use Emotional Cues and Content to Engage Consumers

Emotions play a powerful role in priming consumers’ assessment of information and choice. Messaging strategies in public reports should engage people by conveying information in a manner that is emotionally resonant with the target audience. Specifically, report developers should (a) pay more attention to the emotional or affective power of words used in reports, (b) recognize that choosing a health care provider can create anxiety, and (c) provide messages that help consumers reduce anxiety by gaining a sense of control.

Report designers might also wish to pay more attention to the emotional content conveyed in public reports. As websites increasingly incorporate narrative comments from consumers, the emotional nuances conveyed in these comments can be essential for engaging some consumers who might otherwise find performance reports to be dry and uninteresting. But more attention must also be given to how these emotionally laden commentaries can be effectively balanced and integrated by consumers as they make choices about where to seek medical care (Schlesinger et al., 2013).

Provide Content That Is Relevant to the Choice Situation

A context-driven approach to public reporting will require matching the content of performance measures to meet the decision needs of specific audience segments. This contrasts with the current “supply-driven” approach of presenting all the performance metrics readily available even if not relevant to the intended audience. Specifying and collecting quality metrics to address specific contexts will be a significant undertaking, but one that is essential if public reporting is to fulfill its potential in facilitating better choices. Research is needed to learn which measures are most relevant to promote sound decision making by consumers in specific choice contexts.

It also follows, from these same considerations, that public reports may need to increasingly rely on interactive websites to be effectively tailored to different target audiences. Because different subsets of consumers will find different aspects of care salient, it is essential that they have the capacity to “probe down” into aggregated performance metrics where they are so motivated, but presented with other information that has been “rolled up” into a limited number of aggregate measures. In other words, public reports need to be made more adaptive—and to convey to users a better understanding of how to make use of their interactive features.

For contexts where consumers’ emotional states are likely to require specialized content to defuse anxiety or reduce feelings of vulnerability to a specific health threat (e.g., a recently diagnosed illness), the specialized content may often be most easily provided in a separate report designed for that audience, rather than through an interactive website for a more diverse audience. Because a person with a newly diagnosed serious illness will often seek far more information and support than developers of public reports on health care quality are able to provide, the most effective response will often involve partnerships with nonprofit organizations or patient advocacy groups centered on that specific patient population. Partners who represent or work closely with the specific patient population are often in a position to help customize the content, provide complementary information, and assist with effective dissemination. In addition, they will be more trusted (regarding this condition-specific content) and better able to tap into ancillary resources (e.g., volunteers with relevant personal experience) that can assist consumers making sense of extensive performance metrics and sorting through their treatment options.

Integrate and Summarize Information and Measures

Choosing a health care provider while making full use of publicly reported information on quality (and integrating that with information about cost, location, and network membership) can easily reach levels of complexity exceeding most consumers’ cognitive capacity. Because people are not very good at integrating information about several disparate attributes into an overall evaluation, quality reports should help with integration, for example, by providing “roll-up” scores that summarize across dimensions. And because consumers are often unfamiliar with the quality concepts underlying some measures, quality reports must explain the data they provide and educate consumers how to think about quality (Hibbard, Greene, & Daniel, 2010). However, as we noted above, for some subsets of consumers these two strategies may work at cross purposes, leading to more engaged, but less educated, decision makers.

Provide Personal Navigation and Support

The challenges of interpreting even the best designed performance reports suggest that many consumers—particularly when their capacity for learning is constrained by debilitating illness or failed medical care—will find it daunting to make sense of public reports in ways that feel relevant to their personal circumstances, unless they are supported by individuals serving as interpreters, translators, and navigators. Past demonstration projects have shown that this sort of personalized support and assistance can effectively increase access and reduce anxiety for patients (Aiello Bowles et al., 2008; Dohan & Schrag, 2005). In our assessment, this sort of assistance should be expanded beyond disadvantaged communities, to provide enhanced public investments in interpretation and guidance for a wider array of vulnerable consumers.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) requires this sort of support for the 30 million Americans expected to participate in the new insurance exchanges; since 1990, Medicare has provided this sort of assistance through its State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP; Tracy et al., 2010). Although this leaves the majority of Americans without comparable support, it provides a template for the sort of assistance that could be made available. More specifically, the PPACA identifies two distinct roles for assistance: the first, termed navigators are intended to help consumers make informed choices under everyday circumstances. The second, termed consumer assistance (also known as advocates) are expected to help consumers cope with problems that arise in getting timely access to needed medical care (Grob et al., 2013). The former role seems particularly useful for consumers who have become disconnected from health care because of external disruptions, the latter who have suffered from problematic medical experiences.

Conclusions

Patient engagement with performance reports does not come easily. To be sure, this reflects in part logistical barriers that impede timely distribution and the challenges of developing coherent formats for presenting complex performance metrics. Our central contention in this article, however, is that the most fundamental impediments involve the challenges individual consumers face as they try to interpret this information and extract its relevance for their personal circumstances.

Inducing real and lasting engagement depends crucially on meeting patients on their own terms—and recognizing that these terms will differ in fundamental ways as health needs change and health care experiences accumulate. Simply compiling an array of performance measures—no matter how clearly explained and cleverly presented—will not generally be sufficient. Both the form and nature of performance reports need to be adapted to patients’ varied circumstances: the former by being more attentive to the role of emotional heuristics and cognitive limitations in making health care choices, the latter by incorporating multiple report designs targeted to different audiences with distinct styles of engagement.

Consumers who lack experience in a given context often have little sense of what sorts of information they actually need. Consequently, public reporting initiatives must be designed to guide people through this process of making sense of information, not only in cognitive terms, but also in the context of emotional states that place additional barriers to effective information processing and decision making.

Under these circumstances, it is neither sufficient to exhort patients to be “responsible consumers” nor is it acceptable to try to impose this responsibility by placing patients at increased financial risk. Real engagement requires meeting patients with a helping hand to facilitate their efforts to make use of information relevant to their medical decisions. Having enough helping hands to make this possible requires both ongoing funding and the investment in infrastructure that can “reach out” to patients, discern their circumstances, adapt the contents of performance reports to make them readily understood, and reliably deploy them to promote better, more thoughtful choices.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This article is based on a paper prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National Summit on Public Reporting for Consumers (March 23, 2011), which was supported by AHRQ. Additional support for preparing this article was provided by cooperative agreements (U18HS016980 and 1U18HS016978) from AHRQ.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aiello Bowles EJ, Tuzzio L, Wiese CJ, Kirlin B, Greene SM, Clauser SB, Wagner EH. Understanding high-quality cancer care: A summary of expert perspectives. Cancer. 2008;112:934–942. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aligning Forces for Quality. Consumer decision points in accessing health care information. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/web-assets/2010/07/consumer-decision-points-in-accessing-comparative-health-care-in.pdf.

- Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America (Public Heath Reports) Washington, DC: Association of Schools of Public Health; 2004. Retrieved from http://www.rwjf.org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-research/2004/05/the-growing-burden-of-chronic-disease-in-america.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong AW, Watson AJ, Makredes M, Frangos JE, Kimball AB, Kvedar JC. Text-message reminders to improve sunscreen use: A randomized, controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Archives of Dermatology. 2009;145:1230–1236. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California HealthCare Foundation. From here to maternity: Birth of an online marketing campaign (Issue Brief) 2009 Retrieved from http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/C/PDF%20CalHospCompareMaternity.pdf.

- Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, Sweeney J. Patient and family engagement: A framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Affairs. 2013;32:223–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celsi RL, Olson JC. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. Journal of Consumer Research. 1988;15:210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Advancing Health. Getting tools used: Lessons for health care from successful consumer decision aids. Washington, DC: Author; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.cfah.org/activities/tools.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JB, Volmar KM, Alexander J, Scanlon DP. A report card on provider report cards: Current status of the health transparency movement. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:1235–12441. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day R, Nadash P. New state insurance exchanges should follow the example of Massachusetts by simplifying choices among health plans. Health Affairs. 2012;31:982–989. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: Current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104:848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle MD. Systematic review: The evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:111–123. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goold SD, Klipp G. Managed care members talk about trust. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;54:879–888. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray GM, Ropeik DP. Dealing with the dangers of fear: The role of risk communication. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2002;21(6):106–116. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.6.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grob R, Schlesinger M, Davis S, Cohen D, Lapps J. The Affordable Care Act’s plan for consumer assistance with insurance moves states forward but remains a work in progress. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2013;32:347–356. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured and does it matter? Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79:613–639. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Greene J, Daniel D. What is quality anyway? Performance reports that clearly communicate to consumers the meaning of quality of care. Medical Care Research & Review. 2010;67:275–293. doi: 10.1177/1077558709356300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs LR, Shapiro RY. Questioning the conventional wisdom on public opinion toward health reform. PS: Political Science & Politics. 1994;27:208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2008 Update on consumers’ views of patient safety and quality information. 2008 Oct; Retrieved from http://kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/2008-update-on-consumers-views-of-patient-2/

- Kanouse DE, Spranca M, Vaiana M. Reporting about health care quality: A guide to the galaxy. Health Promotion Practice. 2004;5:222–231. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kőszegi B. Health, anxiety and patient behavior. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22:1073–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MN, Romano PS, Davies HT. How do we maximize the impact of the public reporting of the quality of care? International Journal of Quality in Health Care. 2004;16(Suppl 1):57–63. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Davies HT, Smith PC. Public reporting on quality in the United States and the United Kingdom. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2003;22(3):134–148. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May ML, Stengel DB. Who sues their doctors? How patients handle medical grievances. Law & Society Review. 1990;24:105–120. [Google Scholar]

- McGee J, Kanouse DE, Sofaer S, Hargraves JL, Hoy E, Kleimann S. Making survey results easy to report to consumers: How reporting needs guided survey design in CAHPS. Medical Care. 1999;37:MS32–MS40. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, Meyer S. Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:657–668. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TE, Horowitz CR. Disclosing doctors’ incentives: Will consumers understand and value the information? Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2000;19(4):149–155. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne S, Sheeran P, Orbell S. Prediction and intervention in health-related behavior: A meta-analytic review of protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30:106–143. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Community Measurement. Minnesota health scores. 2012a Retrieved from http://www.mnhealthscores.org/

- Minnesota Community Measurement. Minnesota health scores. The d5. 2012b Retrieved from http://mnhealthscores.org/thed5/

- Minnesota Management & Budget. 2012 Minnesota health plan clinic directory. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.mmb.state.mn.us/insdir/provider_directory.aspx.

- Mitchell S, Schlesinger M. Managed care and gender disparities in problematic healthcare experiences. Health Services Research. 2005;40:1489–1513. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Hospital Discharge Survey. 2007 Summary. National Health Statistics Reports. 2010;29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Larson C. Patients’ good and bad surprises: How do they relate to overall patient satisfaction? Quality Review Bulletin. 1993;19(3):89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil S, Schurrer J, Simon S. Environmental scan of public reporting programs and analysis. Cambridge, MA: Mathematica Policy Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pratkanis AR, Greenwald AG. Consumer involvement, message attention, and the persistence of persuasive impact in a message-dense environment. Psychology & Marketing. 1993;10:321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Rippetoe PA, Rogers RW. Effects of components of protection motivation theory on adaptive and maladaptive coping with a health threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:596–604. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Schlesinger M. Not afraid to blame: The neglected role of blame attribution in medical consumerism and some implications for health policy. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80:41–95. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter RAC, Abraham C, Kok G. Scary warnings and rational precautions: A review of the psychology of fear appeals. Psychology & Health. 2007;16:613–630. [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M. The canary in the Gemeinshaft: Using the public voice of patients to enhance health system performance. In: Hoffman B, Tomes N, Grob R, Schlesinger M, editors. Patients as policy actors. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2011. pp. 148–176. [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M, Druss B, Thomas T. No exit? The effect of health status on dissatisfaction and disenrollment from health plans. Health Services Research. 1999;34:547–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M, Mitchell S, Elbel B. Voices unheard: Barriers to the expression of dissatisfaction with health plans. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80:709–755. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M, Kanouse DE, Rybowski L, Martino SC, Shaller D. Consumer response to patient experience measures in complex information environments. Medical Care. 2012;50:S56–S64. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826c84e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M, et al. Medical Care Research and Review. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shaller D, Sofaer S, Findlay SD, Hibbard JH, Lansky D, Delbanco S. Consumers and quality-driven health care: A call to action. Health Affairs. 2003;22(2):95–101. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinaiko AD, Eastman D, Rosenthal MB. How report cards on physicians, physician groups, and hospitals can have greater impact on consumer choices. Health Affairs. 2012;31:602–611. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedens L, Linton S. Judgment under emotional certainty and uncertainty: The effects of specific emotions on information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:973–988. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.6.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy CE, Benjamin C, Barber C. Making health care reform work: State consumer assistance programs. New York, NY: Community Service Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tu HT, Lauer JR. Word of mouth and physician referrals still drive health care provider choice. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2008. (HSC Research Brief No. 9) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, Loewenstein G, editors. Do emotions help or hurt decision making? A hedgefoxian perspective. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27:591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wofford MM, Wofford JL, Bothra J, Kendrick SB, Smith A, Lichstein PR. Patient complaints about physician behaviors: A qualitative study. Academic Medicine. 2004;79:134–138. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Your Health Matters. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.yourhealthmatters.org/index.php.