ABSTRACT

Sporulation-related repeat (SPOR) domains are small peptidoglycan (PG) binding domains found in thousands of bacterial proteins. The name “SPOR domain” stems from the fact that several early examples came from proteins involved in sporulation, but SPOR domain proteins are quite diverse and contribute to a variety of processes that involve remodeling of the PG sacculus, especially with respect to cell division. SPOR domains target proteins to the division site by binding to regions of PG devoid of stem peptides (“denuded” glycans), which in turn are enriched in septal PG by the intense, localized activity of cell wall amidases involved in daughter cell separation. This targeting mechanism sets SPOR domain proteins apart from most other septal ring proteins, which localize via protein-protein interactions. In addition to SPOR domains, bacteria contain several other PG-binding domains that can exploit features of the cell wall to target proteins to specific subcellular sites.

KEYWORDS: FtsN, cell division, divisome, murein

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial cell division is a complex process mediated by over 30 distinct proteins that assemble into a contractile ring typically referred to as the divisome or septal ring (1–4). A lot of effort has been invested in understanding the mechanisms of septal ring assembly because this knowledge is expected to shed light on deeper questions about how bacterial division is regulated in time and space. The upshot of these studies is that septal ring assembly is driven primarily by a network of protein-protein interactions, whereby a new division protein is recruited by binding to proteins that localized ahead of it (see, e.g., references 1, 5, and 6). But some division proteins with peptidoglycan (PG) binding domains are recruited to the septal ring by their affinity for septal PG rather than their affinity for other division proteins (see, e.g., references 7, 8, and 9). This minireview focuses on one important type of PG binding domain used to target proteins to the division site, namely, the “sporulation-related repeat” or “SPOR” domain (Pfam 05036) (10–13). SPOR domains serve as septal targeting domains on account of their affinity for denuded glycans, regions where the PG lacks peptide sidechains (11, 14, 15) (Fig. 1A). Denuded glycans are generated in septal PG by cell wall amidases that cleave septal PG to allow daughter cell separation (16).

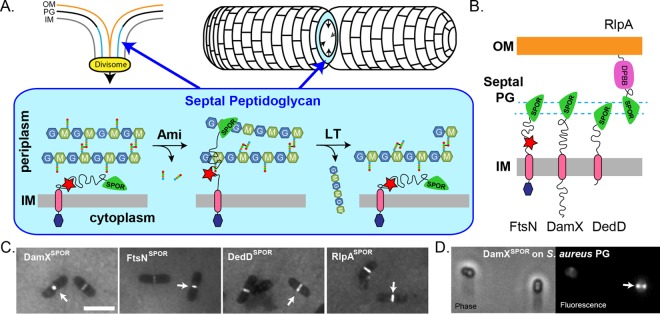

FIG 1.

(A) Model for transient recruitment of E. coli FtsN to the divisome by binding to denuded glycans in septal PG. Denuded glycans are created by cell wall amidases (Ami) and destroyed by lytic transglycosylases (LT). OM, outer membrane. IM, inner membrane. (B) Cartoon of the four SPOR domain proteins of E. coli. Two regions of FtsN that activate sythesis of septal PG are denoted: the cytoplasmic domain (purple hexagon), which binds to FtsA, and a short peptide (red star) whose interaction partner is not yet defined. RlpA has a DPBB (double-psi beta barrel) domain. In P. aeruginosa RlpA, the DPBB domain is an LT. (C) Fluorescence micrographs showing binding of purified GFP-tagged SPOR domains to purified PG sacculi from E. coli. Arrows point to some examples of septal localization. Bar, 5 µm. (D) Paired phase and fluorescence micrographs showing that the purified GFP-tagged SPOR domain from DamX of E. coli binds to septal PG in purified sacculi from S. aureus. The sacculi were treated with hydrofluoric acid to remove teichoic acids. (This figure is modified from reference 15.)

Chances are good that your favorite organism has a SPOR domain protein, if not several of them. The current release of the Pfam database includes 3,795 sequences from 1,353 bacterial species (Pfam 30.0, June 2016) (10). The model organisms Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis have four and three SPOR domain proteins, respectively (Table 1). Nevertheless, some bacteria lack SPOR domain proteins (Table 1). Why is it that most bacteria have SPOR domains but some do not? The absence of SPOR domain proteins in Mycoplasma spp., which lack a PG cell wall, is easy to explain. But outside of this example, there is no obvious rhyme or reason to the complex distribution of SPOR domains among various types of bacteria. For instance, SPOR domains do not track with any simple phylogenetic or morphological traits, such as Gram positive versus Gram negative or rod versus sphere (Table 1). It stands to reason that SPOR domains would be found only in bacteria that have cell wall amidases, as these are required for generating the denuded glycans to which SPOR domains bind. However, all of the organisms listed in Table 1 are predicted to encode at least one cell wall amidase, with the exception of Mycoplasma. Of course, the mere presence of a predicted cell wall amidase does not guarantee the presence of denuded glycans, as illustrated by Streptococcus pneumoniae, which lacks SPOR domains and uses an endopeptidase (PcsB) and a glucosaminidase (LytB) to process septal PG (17–19). S. pneumoniae has a cell wall amidase (LytA), but it seems to function in autolysis rather than cell division even though it localizes to the division site (20). Thus, S. pneumoniae might not have any denuded glycans even though it has a cell wall amidase. SPOR domains are also absent from Staphylococcus aureus, and from most other staphylococcus species, for that matter. Despite this, S. aureus has a cell wall amidase (Atl) that is involved in daughter cell separation (21). Two observations argue that SPOR domains would function properly in S. aureus if they were present. First, at least one member of the genus, Staphylococcus sp. strain CAG324, has a predicted SPOR domain protein (10). Second, an E. coli SPOR domain localizes to septal regions of PG sacculi purified from S. aureus (Fig. 1D), indicating that denuded glycans are enriched in septal PG from this organism. Collectively, these observations suggest the absence of SPOR domains in S. aureus (and perhaps in other bacteria as well) reflects evolutionary happenstance rather some aspect of the organism's physiology.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of SPOR domain proteins in select bacteria

| Organism(s) (no. of SPOR domain proteins)a | Morphology or comment | Amidase present?b |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria with SPOR domains | ||

| Escherichia coli (4), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5), Haemophilus influenzae (2), Acinetobacter baumannii (3), Myxococcus xanthus (1), Coxiella burnetii (4), Bacillus subtilis (3), Peptoclostridium difficile (1), Clostridium perfringens (1), Clostridium cellulovorans (3), Aquifex aeolicus (4) | Rod | Yes |

| Staphylococcus sp. strain CAG:324 (1), Neisseria meningitidis (3), Moraxella catarrhalis (2), Agmenellum quadruplicatum (also called Synechococcus strain 7002) (1) | Sphere | Yes |

| Caulobacter crescentus (3), Vibrio cholerae (6), Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus (1) | Curved | Yes |

| Campylobacter jejuni (2), Helicobacter pylori (2), Treponema pallidum (1), Borrelia burgdorferi (2) | Helical | Yes |

| Bacteria without SPOR domains | ||

| Mycobacteria | Rod; unusual cell wall | Yes |

| Chlamydia | Rod/sphere; limited PG | Yes |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus | Ovoid, spherical | Yes |

| Planctomyces | Ovoid to spherical | Yes |

| Mycoplasma | Variable; no PG | No |

Gram-positive organism designations are in boldface.

Data were determined based on the presence or absence of at least one annotated cell wall amidase gene in the genome sequence. In most cases, nothing is known about whether the putative amidase is functional.

MANY SPOR DOMAIN PROTEINS HELP TO REMODEL THE PG SACCULUS

The vast majority of SPOR domain proteins are known only as sequences in a database, but the handful that have been characterized are sufficient to establish a major theme—SPOR domain proteins help to remodel the PG sacculus, especially (but not exclusively!) during cell division. For example, E. coli has four SPOR domain proteins—DamX, DedD, FtsN, and RlpA—all of which are involved in cell division (Fig. 1B) (11, 13, 22). Exactly what these proteins do to facilitate cytokinesis remains a subject of intense investigation.

FtsN is the one that we know the most about. It activates synthesis of septal PG, and although regions of the protein that mediate this activity have been defined (Fig. 1B), how they communicate with the PG synthesis machinery is not yet clear (11, 23, 24). The outer membrane lipoprotein RlpA does not have a defined function in E. coli, but in Pseudomonas aeruginosa it is a PG hydrolase that contributes to daughter cell separation (25). More formally, P. aeruginosa RlpA (PaRlpA) is a lytic transglycosylase (LT), an enzyme that cleaves glycosidic bonds in the carbohydrate backbone of PG (26, 27). PaRlpA is unusual for an LT in that it degrades only glycans that lack stem peptides, the structure to which it is targeted by its SPOR domain (25). DamX and DedD of E. coli are clearly involved in cell division, but their biochemical activities have yet to be defined (11, 13). Paradoxically, the most salient property of DamX may be its propensity to inhibit cell division when overproduced (28). While this phenotype clearly smacks of an artifact, according to a recent report damX is highly induced when uropathogenic E. coli is grown under conditions that mimic the bladder, resulting in the formation of filamentous cells similar to those observed in samples from people suffering from bladder infections (29). It is thought that filamentation contributes to virulence by obstructing phagocytosis and improving adherence of the bacteria to bladder cells (30). Another SPOR domain protein that has been linked to pathogenesis is MldA of Peptoclostridium difficile, the leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (31, 32). The precise function of MldA is unclear, and it lacks telltale homologies outside the SPOR domain, but the protein localizes to the division site and an mldA insertion mutant exhibits division and shape defects. In contrast, sporulation and germination are normal in the mldA mutant. Interestingly, MldA is required for virulence in a hamster model of infection (31). Because the protein is found only in P. difficile and a few close relatives, it might be a target for a “silver bullet” antibiotic that does not disrupt the entire microbiota of the gut.

SPOR domain proteins involved in morphological processes distinct from cell division are generally less well characterized but no less interesting. The name “SPOR domain” reflects the fact that some of the earliest examples came from proteins involved in sporulation in B. subtilis (33). The most prominent of these is CwlC, a cell wall amidase that degrades mother cell PG to release the mature spore (34, 35). More recently, a dd-carboxypeptidase with a SPOR domain was found to be essential for bacteroid development during the symbiosis of Bradyrhizobium sp. strain OR278 with the legume Aeschynomene indica (36). dd-Carboxypeptidases remove the terminal d-alanine from peptide side chains, thereby limiting the extent of cross-linkage in the sacculus (26, 37). A Bradyrhizobium mutant lacking the dd-carboxypeptidase in question retained normal growth and rod morphology in laboratory media, but most nodules were necrotic and the few that looked relatively healthy nevertheless contained grossly misshapen bacteroids. A final example of a SPOR domain protein serving in a process distinct from cell division comes from Vibrio parahaemolyticus. This organism has two cell types. It grows in liquid as a swimmer cell, a short rod with a single polar flagellum. Upon contact with a surface (or in a viscous environment), the organism differentiates into a swarmer cell, an elongated rod with hundreds of lateral flagella (38). During swarmer cell differentiation, a predicted outer membrane lipoprotein with a SPOR domain is induced over 100-fold (39). This protein, named VPA1294, consists of a SPOR domain connected to the outer membrane by a 24-amino-acid linker. The possibility that VPA1294 inhibits division cannot be excluded, but we think that a more likely role is that of tethering the outer membrane to the PG layer. This idea is attractive because the protein is so small and because the abundance of lateral flagella poking through the cell envelope cries out for some form of reinforcement.

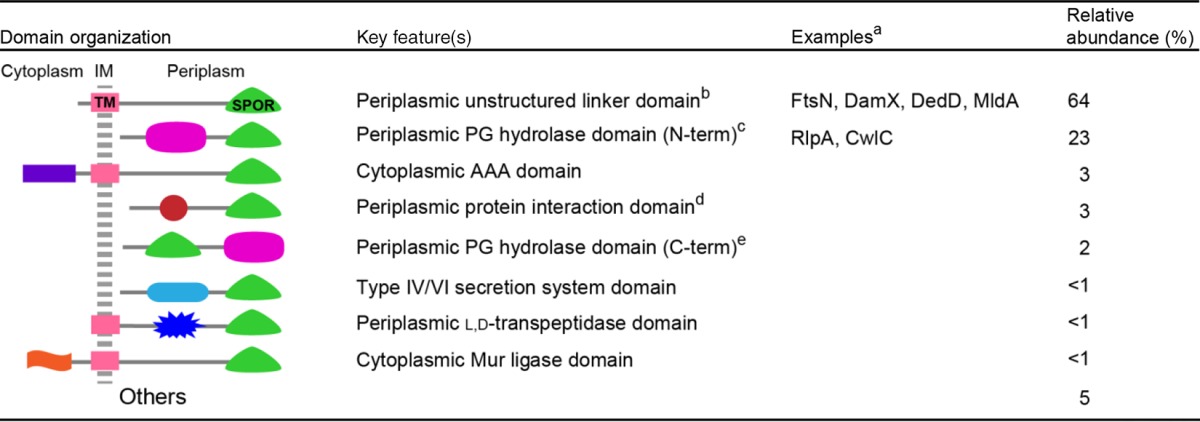

Another perspective on the function of SPOR domain proteins comes from mining sequence databases to see what other domains are present in these proteins. The Pfam database organizes SPOR domain proteins into 129 distinct architectures according to the identity and arrangement of the various domains in each protein (10). A greatly simplified version of this classification scheme is presented in Table 2. The single most abundant architecture, comprising over 60% of the sequences, corresponds to the overall arrangement of FtsN, DamX, DedD, and MldA—all of which are part of the apparatus that remodels PG during cell division. The hallmark of this set is a relatively large periplasmic “linker” region with low sequence complexity. This region is often predicted to be intrinsically disordered. “Linker” is in quotes because this region in FtsN includes three short poorly formed helices (40) and because disordered domains often engage in protein-protein interactions (41, 42). Exactly how SPOR domain proteins with this architecture contribute to cell division is not clear. Like FtsN, they could allosterically regulate enzymes in the division apparatus, but other reasonable possibilities include stabilizing cell wall-associated protein complexes and/or tethering the inner membrane to the PG layer. The remaining SPOR proteins are distributed among various architectures. About 20% have domains implicated in hydrolysis or, less often, in synthesis of PG (Table 2). The hydrolase domains are quite diverse, encompassing enzymes that shorten the stem peptides, remove them entirely, or cleave the glycan backbone of PG. A few SPOR domain proteins have domains suggestive of a role in PG synthesis, such as l,d-transpeptidase (presumably to cross-link PG) and Mur ligase (presumably to make PG precursors). Finally, about 10% of SPOR domain proteins fall into various categories, most of which are not obviously related to PG. In summary, evolution regards SPOR domains as portable PG-binding and/or septal targeting domains and has transplanted these domains onto a multitude of proteins that are involved in various capacities in the biogenesis of the PG sacculus.

TABLE 2.

SPOR domain proteins have diverse architectures

Only proteins discussed in this minireview are listed by name.

The largely unstructured region of FtsN has three poorly formed helices and activates synthesis of septal PG. TM, transmembrane helix.

RlpA has a DPBB (double-psi beta barrel) domain with lytic transglycosylase activity in P. aeruginosa and V. parahaemolyticus (unpublished data). The proteins in this category have diverse N termini (N-term), including predicted transmembrane domains, cleavable signal sequences, and sites for covalent attachment of a lipid that would anchor the protein to the outer membrane (as is the case for RlpA). The potential PG hydrolase domains lumped into this architecture are Amidase_2, Amidase_3, DPBB, glucosaminidase, Glycohydrolase_25, NAGPA, NLPC_P60, Peptidase_S11, Peptidase_S13, Peptidase_M23, SLT, SLT_2, Peptidase_S8, and Peptidase_C25.

Putative interaction domains include various TPR domains, Sel1, SHOCT, Usher, PD40, and bacterial SH3.

The potential PG hydolase domains found C terminal to a SPOR domain include glucosaminidase, NAGPA, NLPC_60, Polysaccharide deacetylase_1, SpoIID, and Trypsin_2.

SPOR DOMAINS BIND TO DENUDED GLYCANS, A HALLMARK OF SEPTAL PG

Vollmer's laboratory was the first to show that SPOR domains bind to PG (14). The key finding was that the SPOR domain from FtsN of E. coli cosedimented with whole PG sacculi upon centrifugation. This discovery did not immediately lead to the realization that FtsN′s SPOR domain targets the protein to the division site for two reasons. First, the assay did not specifically implicate septal PG as the binding site because it was not feasible at that time, nor is it feasible now, to isolate a septal PG fraction for use in binding studies. Second, deleting the SPOR domain from FtsN did not compromise cell division (14), as if the PG binding activity were not very important. That paradoxical result was explained years later by Busiek and Margolin, who showed that a small (but sufficient) amount of FtsN is recruited to the division site via the interaction of FtsN′s cytoplasmic domain with FtsA (43).

The general importance of SPOR domains as septal targeting domains came into focus with a trio of papers published in 2009 to 2010 by Gerding et al., Möll et al., and ourselves (11–13). In brief, those papers identified and characterized a host of “new” SPOR domain proteins, showed they were involved in cell division in a variety of bacteria, and demonstrated that isolated SPOR domains localize sharply to the midcell when produced as green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusions and exported to the periplasm via the Tat system. In addition, we demonstrated that PG binding is a general property of SPOR domains (13), while de Boer showed drugs or mutations that alter biogenesis of septal PG impair recruitment of SPOR domains to the division site (11). In particular, SPOR domains failed to localize in an E. coli triple amidase mutant (11).

The dependence of septal localization on cell wall amidases pointed the way toward understanding how SPOR domains distinguish septal PG from PG elsewhere around the sacculus. As the name suggests, cell wall amidases cleave the amide bond that joins stem peptides to MurNAc sugars in the glycan backbone of PG (26, 27). The end products of this reaction are free peptides and “denuded” glycans. Because amidases are important for processing septal PG to facilitate separation of daughter cells (8, 16, 45), it seemed likely that denuded glycans are enriched in septal PG. Moreover, Vollmer's group had shown that SPOR domains can bind to denuded glycans (14).

At this point one could be forgiven for thinking that the problem of the basis of SPOR domain recruitment had been solved, but a couple of nagging issues needed to be addressed. First, because all the localization work had been done in vivo, it was impossible to exclude the possibility that SPOR domains target a septal protein rather than the PG itself. Second, the notion that denuded glycans are enriched in septal PG was an inference, not an established fact—the difficulty of isolating a septal PG fraction prevented determining the chemical composition of septal PG.

These issues were laid to rest by using fluorescence microscopy to visualize purified GFP-SPOR fusion proteins bound to isolated PG sacculi (15). This assay revealed GFP-SPOR proteins derived from DamX, DedD, FtsN, and RlpA localized to division sites (Fig. 1C). Follow-up experiments verified that denuded glycans are indeed the physiologically relevant binding targets. First, binding was not observed using sacculi from an E. coli triple amidase mutant but was greatly enhanced using sacculi from an E. coli mutant lacking five lytic transglycosylases, enzymes that degrade the glycan backbone of PG. Second, treating purified sacculi with an amidase to generate more denuded glycans increased GFP-SPOR binding. Conversely, treating sacculi with a lytic transglycosylase specific for denuded glycans essentially eliminated SPOR domain binding. In toto, these findings support a model for recruitment of SPOR domain proteins to the division site based on the transient availability of denuded glycans (Fig. 1A).

IMPLICATIONS FOR BIOGENESIS OF SEPTAL PG

Besides providing compelling evidence that the physiologically relevant binding site is a denuded glycan, the in vitro localization assay revealed that denuded glycans are indeed enriched in septal PG. What's more, this was shown to be true in both E. coli and B. subtilis (15), organisms whose evolutionary paths diverged over 1 billion years ago. More recently, we extended this paradigm to S. aureus, an organism that does not even have SPOR domain proteins (Fig. 1D). Thus, the ordered, sequential activity of cell wall amidases followed by enzymes that degrade the glycan backbone is an ancient and widespread feature of bacterial cell division. How PG hydrolases are regulated to ensure that amidases act first is a mystery because most purified lytic transglycosylases and other enzymes that target glycosidic linkages are active on cross-linked PG (26, 27, 46–48). Most lytic transglycosylases in E. coli are tethered to the outer membrane (27, 47), which likely restricts their access to septal PG until after the amidases have had their turn. However, regulatory mechanisms that invoke the outer membrane cannot account for the sequential activity of PG hydrolases in Gram-positive organisms.

SPOR DOMAINS EXHIBIT AN RNP FOLD AND A CONSERVED PG-BINDING SITE

SPOR domains are about 70 amino acids long and consist of two degenerate 35-residue repeats (10). At the level of primary structure, SPOR domains are not highly conserved and typically exhibit <20% amino acid identity in pairwise alignments (10, 13), making them difficult to detect using BLAST searches. Nevertheless, these domains share a core tertiary structure comprising a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet buttressed on one side by two α-helices (Fig. 2) (40, 44, 49). This structure places SPOR domains in the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) fold superfamily. RNP folds were first identified in mRNA splicing proteins from eukaryotes, but RNP folds are quite common and are not associated with any particular ligand (50).

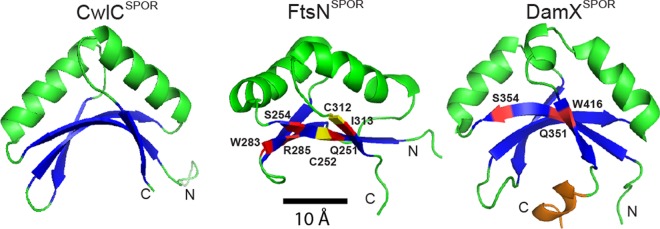

FIG 2.

Comparison of SPOR domains from CwlC (PDB entry 1X60), FtsN (PDB entry 1UTA), and DamX (PDB entry 2FLV). The core fold is an antiparallel β-sheet (blue) flanked on one side by two helices (green). DamXSPOR has an additional helix (gold) that is relatively mobile. Amino acids highlighted in red are important for septal localization and PG binding. The two cysteines that form a disulfide in FtsN are highlighted in yellow.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the SPOR domains from DamX and FtsN revealed that amino acids in and near the β-sheet are critical for septal localization and PG binding (Fig. 2) (49, 51). However, it is not yet possible to model the SPOR:PG complex to address issues such as whether the presence of stem peptides sterically blocks binding of the glycan chain to the protein. Mutagenesis of the SPOR domain from FtsN led to the unexpected discovery of a disulfide bond that is critical for the stability of the domain (51). Subsequently, Beckwith's group demonstrated that the disulfide is required for the overall stability of FtsN, so much so, in fact, that when an E. coli disulfide bond (dsb) mutant is grown anaerobically, FtsN is almost completely degraded and division fails (52). The essential nature of FtsN′s disulfide had been overlooked in previous studies of dsb mutants because molecular oxygen and/or oxidized components of the growth medium allow sufficient disulfide bond formation during aerobic growth. About 15% of SPOR domains in the sequence databases have paired cysteines, suggesting that there is a widespread connection between cell division and redox metabolism (51).

WHY TARGET A DIVISION PROTEIN TO A PG STRUCTURE RATHER THAN TO ANOTHER DIVISION PROTEIN?

The abundance of SPOR domains in the bacterial world argues for their utility and raises an important question: do SPOR domains have advantages over protein-protein interactions when it comes to targeting proteins to the division site? The answers to such questions are of course speculative, but we think that the comparative advantage of SPOR domains comes into play in protein evolution and protein function.

Starting with evolution, SPOR domains retain their function even after horizontal gene transfer because their target, the PG wall, is highly conserved. The robustness of SPOR domains with respect to horizontal transfer is underscored by the ability of SPOR domains from B. subtilis, Cytophaga hutchinsonii, and Aquifex aeolicus to target septal PG in E. coli (11, 13). In contrast, protein-protein interactions are mediated by molecular interfaces that are subject to rapid drift (53). As a consequence, a foreign division protein is unlikely to interact productively with its intended partner in the context of a new host. Another advantageous property of SPOR domains is that they lend themselves to the creation of new division proteins by gene fusions. The plethora of domain architectures illustrated in Table 2 suggests that SPOR domains have been grafted onto a lot of proteins over the eons.

Turning now to the functional attributes of SPOR domains, their specificity for septal PG comes in handy in many circumstances. The SPOR domain of PaRlpA, which anchors the enzyme to its substrate, denuded glycans, is a case in point (25). A more nuanced functional advantage of SPOR domains stems from the transient nature of denuded glycans in septal PG. Because denuded glycans are a moving target, they link the localization of a SPOR domain protein, and thus its activity, to the actual progress of cell division. Consider FtsN, an activator of septal PG synthesis. The appearance of denuded glycans in septal PG creates a positive-feedback loop that recruits additional FtsN and drives a burst of PG synthesis when and where it is needed (11). Consistent with this notion, synthesis of septal PG sometimes fails to reach completion in amidase mutants (16, 54, 55). Paradoxically, tethering FtsN to denuded glycans might also create a negative-feedback loop that prevents synthesis of septal PG from running too far ahead of the PG hydrolases. In other words, a lag in processing of septal PG would retard inward movement of FtsN and thus slow synthesis of septal PG. Coordinating synthesis and processing of septal PG is important in Gram-negative bacteria because splitting of septal PG is required for the outer membrane to invaginate. For reasons that are not known, failure of the outer membrane to constrict compromises this important permeability barrier and renders cells susceptible to antibiotics and noxious compounds such as bile salts (16, 55–57). Several, partially redundant mechanisms help to ensure that the outer membrane constricts in unison with the PG layer and inner membrane (56, 58–60). SPOR domains might also contribute to this process by acting as tethers and/or as regulatory factors whose position is fine-tuned by the interplay of the many proteins involved in assembly of the division septum.

SPOR DOMAINS ARE NOT THE ONLY PG-BINDING DOMAINS THAT CAN TARGET SEPTAL PG

Many bacterial proteins that act on the cell wall contain peptidoglycan binding domains, some of which have been implicated in septal localization. The cell wall amidases AmiB and AmiC of E. coli and the type IVa secretion apparatus of P. aeruginosa are targeted to division sites by peptidoglycan-binding AMIN domains (8, 61–64). One of the most widespread PG-binding domains is the LysM domain, which binds to carbohydrates containing GlcNAc, including PG in bacteria and chitin in eukaryotes (65, 66). LysM domains mediate septal localization of several PG hydrolases in Gram-positive bacteria (9, 67, 68). The underlying mechanism involves wall teichoic acids (WTA), which are covalently attached to PG at MurNAc residues in many Gram-positive species and interfere with LysM domain binding. Division sites are generally zones of intense PG synthesis, so they contain newly synthesized PG with smaller amounts of WTA than the older PG elsewhere around the cell. Curiously, however, LysM domains can also direct proteins to the division site in Gram-negative bacteria (69–71). Since these organisms are devoid of WTA, some other targeting mechanism must come into play. In S. aureus, a PG hydrolase named AtlA is recruited to septal PG by its PG-binding repeat (R) domains (7). Although the binding specificity of R domains is not known, they are directed to septal PG by the same WTA exclusion mechanism as that described above for LysM domains (72).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

SPOR domains have evolved to exploit the transient accumulation of denuded glycans in septal PG to target proteins to the division site. The utility of this targeting mechanism is highlighted by the presence of predicted SPOR domain proteins in many bacterial genomes and the evidence that denuded glycans accumulate transiently in the septal PG of a wide range of bacteria.

While the basic outlines of SPOR domain function are now in place, we still have a lot to learn about how SPOR domains recognize denuded glycans. Determining the structure of a SPOR domain bound to a denuded glycan will shed light on the binding mechanism, especially with respect to which chemical groups on the glycan interact with the protein and why the presence of peptide sidechains interferes with binding. Many bacteria use N-deacetylation or O-acetylation of the glycan backbone of PG as a defense against lysozyme (73), and it will be interesting to learn whether these modifications affect SPOR domain binding. Having a structure for a SPOR:glycan complex might facilitate the development of small-molecule inhibitors with therapeutic potential. In this context, it is worth noting that bacterial mutants lacking SPOR domain proteins are often sensitized to multiple antibiotics or are conditionally lethal (13, 25, 74–77), suggesting that these proteins might be exploited as targets for codrugs that improve the efficacy of existing antibiotics.

The fact that many bacteria have multiple SPOR domain proteins raises questions about binding specificity. Do the various SPOR domains have different binding preferences and target different sites at the septum? Or do SPOR domain proteins compete for the same binding sites—and, if so, who has priority? Another important knowledge gap is that little is known about the precise biochemical functions of most SPOR domain proteins—not just the comparatively well-studied ones that play ill-defined roles in E. coli cell division but also the thousands more that are known only as sequences in a database. These questions are likely to keep microbiologists busy for years to come.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank anonymous reviewers for insightful comments on the initial draft of the manuscript.

Cell division work in the Weiss laboratory is supported by a Stinski Development Grant from the Department of Microbiology at The University of Iowa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Egan AJ, Vollmer W. 2013. The physiology of bacterial cell division. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1277:8–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haeusser DP, Margolin W. 2016. Splitsville: structural and functional insights into the dynamic bacterial Z ring. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:305–319. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutkenhaus J, Pichoff S, Du S. 2012. Bacterial cytokinesis: from Z ring to divisome. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 69:778–790. doi: 10.1002/cm.21054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Söderstrom B, Daley DO. 8 July 2016. The bacterial divisome: more than a ring? Curr Genet doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karimova G, Dautin N, Ladant D. 2005. Interaction network among Escherichia coli membrane proteins involved in cell division as revealed by bacterial two-hybrid analysis. J Bacteriol 187:2233–2243. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2233-2243.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goehring NW, Beckwith J. 2005. Diverse paths to midcell: assembly of the bacterial cell division machinery. Curr Biol 15:R514–R526. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baba T, Schneewind O. 1998. Targeting of muralytic enzymes to the cell division site of Gram-positive bacteria: repeat domains direct autolysin to the equatorial surface ring of Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J 17:4639–4646. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. 2003. The Escherichia coli amidase AmiC is a periplasmic septal ring component exported via the twin-arginine transport pathway. Mol Microbiol 48:1171–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steen A, Buist G, Leenhouts KJ, El Khattabi M, Grijpstra F, Zomer AL, Venema G, Kuipers OP, Kok J. 2003. Cell wall attachment of a widely distributed peptidoglycan binding domain is hindered by cell wall constituents. J Biol Chem 278:23874–23881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA, Tate J, Bateman A. 2016. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerding MA, Liu B, Bendezu FO, Hale CA, Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. 2009. Self-enhanced accumulation of FtsN at division sites and roles for other proteins with a SPOR domain (DamX, DedD, and RlpA) in Escherichia coli cell constriction. J Bacteriol 191:7383–7401. doi: 10.1128/JB.00811-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Möll A, Thanbichler M. 2009. FtsN-like proteins are conserved components of the cell division machinery in proteobacteria. Mol Microbiol 72:1037–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arends SJ, Williams K, Scott RJ, Rolong S, Popham DL, Weiss DS. 2010. Discovery and characterization of three new Escherichia coli septal ring proteins that contain a SPOR domain: DamX, DedD, and RlpA. J Bacteriol 192:242–255. doi: 10.1128/JB.01244-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ursinus A, van den Ent F, Brechtel S, de Pedro M, Höltje JV, Löwe J, Vollmer W. 2004. Murein (peptidoglycan) binding property of the essential cell division protein FtsN from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 186:6728–6737. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6728-6737.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yahashiri A, Jorgenson MA, Weiss DS. 2015. Bacterial SPOR domains are recruited to septal peptidoglycan by binding to glycan strands that lack stem peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:11347–11352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidrich C, Templin MF, Ursinus A, Merdanovic M, Berger J, Schwarz H, de Pedro MA, Höltje JV. 2001. Involvement of N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidases in cell separation and antibiotic-induced autolysis of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 41:167–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinscheid DJ, Gottschalk B, Schubert A, Eikmanns BJ, Chhatwal GS. 2001. Identification and molecular analysis of PcsB, a protein required for cell wall separation of group B streptococcus. J Bacteriol 183:1175–1183. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1175-1183.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartual SG, Straume D, Stamsas GA, Munoz IG, Alfonso C, Martinez-Ripoll M, Havarstein LS, Hermoso JA. 2014. Structural basis of PcsB-mediated cell separation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nat Commun 5:3842. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García P, González MP, García E, López R, García JL. 1999. LytB, a novel pneumococcal murein hydrolase essential for cell separation. Mol Microbiol 31:1275–1281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellroth P, Daniels R, Eberhardt A, Ronnlund D, Blom H, Widengren J, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. 2012. LytA, major autolysin of Streptococcus pneumoniae, requires access to nascent peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem 287:11018–11029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugai M, Komatsuzawa H, Akiyama T, Hong YM, Oshida T, Miyake Y, Yamaguchi T, Suginaka H. 1995. Identification of endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase and N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase as cluster-dispersing enzymes in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 177:1491–1496. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1491-1496.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai K, Xu Y, Lutkenhaus J. 1993. Cloning and characterization of ftsN, an essential cell division gene in Escherichia coli isolated as a multicopy suppressor of ftsA12(Ts). J Bacteriol 175:3790–3797. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3790-3797.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutkenhaus J. 2009. FtsN–trigger for septation. J Bacteriol 191:7381–7382. doi: 10.1128/JB.01100-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B, Persons L, Lee L, de Boer PA. 2015. Roles for both FtsA and the FtsBLQ subcomplex in FtsN-stimulated cell constriction in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 95:945–970. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jorgenson MA, Chen Y, Yahashiri A, Popham DL, Weiss DS. 2014. The bacterial septal ring protein RlpA is a lytic transglycosylase that contributes to rod shape and daughter cell separation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 93:113–128. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. 2008. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:259–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Heijenoort J. 2011. Peptidoglycan hydrolases of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 75:636–663. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyngstadaas A, Løbner-Olesen A, Boye E. 1995. Characterization of three genes in the dam-containing operon of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet 247:546–554. doi: 10.1007/BF00290345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khandige S, Asferg CA, Rasmussen KJ, Larsen MJ, Overgaard M, Andersen TE, Møller-Jensen J. 2016. DamX controls reversible cell morphology switching in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. mBio 7:e00642-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00642-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson PD, Hunstad DA. 2016. Subversion of host innate immunity by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Pathogens 5:E2. doi: 10.3390/pathogens5010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ransom EM, Williams KB, Weiss DS, Ellermeier CD. 2014. Identification and characterization of a gene cluster required for proper rod shape, cell division, and pathogenesis in Clostridium difficile. J Bacteriol 196:2290–2300. doi: 10.1128/JB.00038-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CDC. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer EL, Studholme DJ, Yeats C, Eddy SR. 2004. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuroda A, Asami Y, Sekiguchi J. 1993. Molecular cloning of a sporulation-specific cell wall hydrolase gene of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 175:6260–6268. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6260-6268.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith TJ, Foster SJ. 1995. Characterization of the involvement of two compensatory autolysins in mother cell lysis during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis 168. J Bacteriol 177:3855–3862. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3855-3862.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gully D, Gargani D, Bonaldi K, Grangeteau C, Chaintreuil C, Fardoux J, Nguyen P, Marchetti R, Nouwen N, Molinaro A, Mergaert P, Giraud E. 2016. A peptidoglycan-remodeling enzyme is critical for bacteroid differentiation in Bradyrhizobium spp. during legume symbiosis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 29:447–457. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-16-0052-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh AS, Chowdhury C, Nelson DE. 2008. Physiological functions of d-alanine carboxypeptidases in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol 16:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarter LL. 2001. Polar flagellar motility of the Vibrionaceae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 65:445–462, table of contents. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.3.445-462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gode-Potratz CJ, Kustusch RJ, Breheny PJ, Weiss DS, McCarter LL. 2011. Surface sensing in Vibrio parahaemolyticus triggers a programme of gene expression that promotes colonization and virulence. Mol Microbiol 79:240–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang JC, Van Den Ent F, Neuhaus D, Brevier J, Löwe J. 2004. Solution structure and domain architecture of the divisome protein FtsN. Mol Microbiol 52:651–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmes JA, Follett SE, Wang H, Meadows CP, Varga K, Bowman GR. 2016. Caulobacter PopZ forms an intrinsically disordered hub in organizing bacterial cell poles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:12490–12495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602380113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. 2014. Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annu Rev Biochem 83:553–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Busiek KK, Margolin W. 2014. A role for FtsA in SPOR-independent localization of the essential Escherichia coli cell division protein FtsN. Mol Microbiol 92:1212–1226. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mishima M, Shida T, Yabuki K, Kato K, Sekiguchi J, Kojima C. 2005. Solution structure of the peptidoglycan binding domain of Bacillus subtilis cell wall lytic enzyme CwlC: characterization of the sporulation-related repeats by NMR. Biochemistry 44:10153–10163. doi: 10.1021/bi050624n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uehara T, Parzych KR, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. 2010. Daughter cell separation is controlled by cytokinetic ring-activated cell wall hydrolysis. EMBO J 29:1412–1422. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horsburgh GJ, Atrih A, Williamson MP, Foster SJ. 2003. LytG of Bacillus subtilis is a novel peptidoglycan hydrolase: the major active glucosaminidase. Biochemistry 42:257–264. doi: 10.1021/bi020498c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee M, Hesek D, Llarrull LI, Lastochkin E, Pi H, Boggess B, Mobashery S. 2013. Reactions of all Escherichia coli lytic transglycosylases with bacterial cell wall. J Am Chem Soc 135:3311–3314. doi: 10.1021/ja309036q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheurwater E, Reid CW, Clarke AJ. 2008. Lytic transglycosylases: bacterial space-making autolysins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams KB, Yahashiri A, Arends SJ, Popham DL, Fowler CA, Weiss DS. 2013. Nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of the peptidoglycan-binding SPOR domain from Escherichia coli DamX: insights into septal localization. Biochemistry 52:627–639. doi: 10.1021/bi301609e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varani G, Nagai K. 1998. RNA recognition by RNP proteins during RNA processing. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 27:407–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duncan TR, Yahashiri A, Arends SJ, Popham DL, Weiss DS. 2013. Identification of SPOR domain amino acids important for septal localization, peptidoglycan binding, and a disulfide bond in the cell division protein FtsN. J Bacteriol 195:5308–5315. doi: 10.1128/JB.00911-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meehan BM, Landeta C, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 2 December 2016. The essential cell division protein FtsN contains a critical disulfide bond in a non-essential domain. Mol Microbiol doi: 10.1111/mmi.13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lynch M, Hagner K. 2015. Evolutionary meandering of intermolecular interactions along the drift barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E30–E38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421641112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Priyadarshini R, de Pedro MA, Young KD. 2007. Role of peptidoglycan amidases in the development and morphology of the division septum in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 189:5334–5347. doi: 10.1128/JB.00415-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yakhnina AA, McManus HR, Bernhardt TG. 2015. The cell wall amidase AmiB is essential for Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell division, drug resistance and viability. Mol Microbiol 97:957–973. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gray AN, Egan AJ, Van't Veer IL, Verheul J, Colavin A, Koumoutsi A, Biboy J, Altelaar AF, Damen MJ, Huang KC, Simorre JP, Breukink E, den Blaauwen T, Typas A, Gross CA, Vollmer W. 2015. Coordination of peptidoglycan synthesis and outer membrane constriction during Escherichia coli cell division. Elife 4:e07118. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heidrich C, Ursinus A, Berger J, Schwarz H, Höltje JV. 2002. Effects of multiple deletions of murein hydrolases on viability, septum cleavage, and sensitivity to large toxic molecules in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 184:6093–6099. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6093-6099.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerding MA, Ogata Y, Pecora ND, Niki H, de Boer PA. 2007. The trans-envelope Tol-Pal complex is part of the cell division machinery and required for proper outer-membrane invagination during cell constriction in E. coli. Mol Microbiol 63:1008–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. 2010. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yeh YC, Comolli LR, Downing KH, Shapiro L, McAdams HH. 2010. The caulobacter Tol-Pal complex is essential for outer membrane integrity and the positioning of a polar localization factor. J Bacteriol 192:4847–4858. doi: 10.1128/JB.00607-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rocaboy M, Herman R, Sauvage E, Remaut H, Moonens K, Terrak M, Charlier P, Kerff F. 2013. The crystal structure of the cell division amidase AmiC reveals the fold of the AMIN domain, a new peptidoglycan binding domain. Mol Microbiol 90:267–277. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carter T, Buensuceso RN, Tammam S, Lamers RP, Harvey H, Howell PL, Burrows LL. 2017. The type IVa pilus machinery is recruited to sites of future cell division. mBio 8:e02103-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02103-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peters NT, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. 2011. A fail-safe mechanism in the septal ring assembly pathway generated by the sequential recruitment of cell separation amidases and their activators. J Bacteriol 193:4973–4983. doi: 10.1128/JB.00316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Souza RF, Anantharaman V, de Souza SJ, Aravind L, Gueiros-Filho FJ. 2008. AMIN domains have a predicted role in localization of diverse periplasmic protein complexes. Bioinformatics 24:2423–2426. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buist G, Steen A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. 2008. LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. Mol Microbiol 68:838–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mesnage S, Dellarole M, Baxter NJ, Rouget JB, Dimitrov JD, Wang N, Fujimoto Y, Hounslow AM, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Fukase K, Foster SJ, Williamson MP. 2014. Molecular basis for bacterial peptidoglycan recognition by LysM domains. Nat Commun 5:4269. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frankel MB, Schneewind O. 2012. Determinants of murein hydrolase targeting to cross-wall of Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem 287:10460–10471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamamoto H, Miyake Y, Hisaoka M, Kurosawa S, Sekiguchi J. 2008. The major and minor wall teichoic acids prevent the sidewall localization of vegetative DL-endopeptidase LytF in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 70:297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goley ED, Comolli LR, Fero KE, Downing KH, Shapiro L. 2010. DipM links peptidoglycan remodelling to outer membrane organization in Caulobacter. Mol Microbiol 77:56–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Möll A, Schlimpert S, Briegel A, Jensen GJ, Thanbichler M. 2010. DipM, a new factor required for peptidoglycan remodelling during cell division in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol 77:90–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poggio S, Takacs CN, Vollmer W, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2010. A protein critical for cell constriction in the Gram-negative bacterium Caulobacter crescentus localizes at the division site through its peptidoglycan-binding LysM domains. Mol Microbiol 77:74–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schlag M, Biswas R, Krismer B, Kohler T, Zoll S, Yu W, Schwarz H, Peschel A, Götz F. 2010. Role of staphylococcal wall teichoic acid in targeting the major autolysin Atl. Mol Microbiol 75:864–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vollmer W. 2008. Structural variation in the glycan strands of bacterial peptidoglycan. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:287–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nichols RJ, Sen S, Choo YJ, Beltrao P, Zietek M, Chaba R, Lee S, Kazmierczak KM, Lee KJ, Wong A, Shales M, Lovett S, Winkler ME, Krogan NJ, Typas A, Gross CA. 2011. Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell 144:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tamae C, Liu A, Kim K, Sitz D, Hong J, Becket E, Bui A, Solaimani P, Tran KP, Yang H, Miller JH. 2008. Determination of antibiotic hypersensitivity among 4,000 single-gene-knockout mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 190:5981–5988. doi: 10.1128/JB.01982-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruiz C, Levy SB. 2010. Many chromosomal genes modulate MarA-mediated multidrug resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2125–2134. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01420-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.López-Garrido J, Cheng N, Garcia-Quintanilla F, Garcia-del Portillo F, Casadesus J. 2010. Identification of the Salmonella enterica damX gene product, an inner membrane protein involved in bile resistance. J Bacteriol 192:893–895. doi: 10.1128/JB.01220-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]