Abstract

Background

Studies measuring the completeness and consistency of trial registration and reporting rely on linking registries with bibliographic databases. In this systematic review, we quantified the processes used to identify these links.

Methods

PubMed and Embase databases were searched from inception to May 2016 for studies linking trial registries with bibliographic databases. The processes used to establish these links were categorised as automatic when the registration identifier was available in the bibliographic database or publication, or manual when linkage required inference or contacting of trial investigators. The number of links identified by each process was extracted where available. Linear regression was used to determine whether the proportions of links available via automatic processes had increased over time.

Results

In 43 studies that examined cohorts of registry entries, 24 used automatic and manual processes to find articles; 3 only automatic; and 11 only manual (5 did not specify). Twelve studies reported results for both manual and automatic processes and showed that a median of 23% (range from 13 to 42%) included automatic links to articles, while 17% (range from 5 to 42%) of registry entries required manual processes to find articles. There was no evidence that the proportion of registry entries with automatic links had increased (R 2 = 0.02, p = 0.36). In 39 studies that examined cohorts of articles, 21 used automatic and manual processes; 9 only automatic; and 2 only manual (7 did not specify). Sixteen studies reported numbers for automatic and manual processes and indicated that a median of 49% (range from 8 to 97%) of articles had automatic links to registry entries, and 10% (range from 0 to 28%) required manual processes to find registry entries. There was no evidence that the proportion of articles with automatic links to registry entries had increased (R 2 = 0.01, p = 0.73).

Conclusions

The linkage of trial registries to their corresponding publications continues to require extensive manual processes. We did not find that the use of automatic linkage has increased over time. Further investigation is needed to inform approaches that will ensure publications are properly linked to trial registrations, thus enabling efficient monitoring of trial reporting.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0518-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Clinical trials as topic, Trial registration, Publication bias, Reporting bias, Systematic reviews as topic

Background

Clinical trial registries were established to improve transparency and completeness in the reporting of clinical trials [1–6]. Since they were established, a number of policies have been implemented to encourage or mandate their use, and this has led to substantial growth in the number of trials that have been registered [7–11]. For example, since 2005, prospective trial registration has been a condition for publication in member journals of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [1, 12]. The European Union and USA have also passed legislation requiring prospective registration of clinical trials involving drugs or devices [13].

Clinical trial registries provide the ability to measure biases in the reporting of clinical trials that arise due to non-publication, delayed publication, or incomplete publication of results [14]. Studies examining these issues rely on the ability to establish a link between the original trial registration and subsequent published article. These links can be established in an automatic fashion if the publication abstract or metadata includes the registry identifier [15, 16]. However, if this identifier is not included by trial investigators or added by journals, manual processes are needed to create these links, either through searches and inference or through direct contact with investigators. Despite the number of studies that have examined reporting biases by linking trial registry entries and publications, the processes for linking are variable and poorly described.

Clinical trial registries are a critical source of information for systematic reviewers who use these registries to augment bibliographic database searches when compiling relevant evidence from clinical trials [17–19]. Systematic reviewers may seek to identify links from published trial reports to their respective registry entries to fill in gaps for information that is missing or incompletely reported. They may also independently search trial registries to identify additional trials [20, 21] and follow links from the registry to reports of the trials.

Our aim was to quantify the processes that have been used to link clinical trial registries with published results and to examine the use and utility of automatic linkage over time. To do this, we conducted a systematic review of all studies examining a cohort of clinical trials to identify links from clinical trial registries to bibliographic databases and from bibliographic databases to clinical trial registries, following a published systematic review protocol [22].

Methods

Inclusion criteria and search strategy

We identified all primary studies that examined links between any of the registries in the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and published articles in bibliographic databases. Studies were excluded if there was no English-language version, if they did not unambiguously report the total number of clinical trials for which links were identified, if they were reporting on a specific clinical trial, or if the identification of links was not the primary focus of the study. Studies that did not unambiguously report the processes used to identify links were included in the review but excluded from the analyses.

PubMed and Embase were searched from inception to May 27, 2016, [23, 24]. The search strategy was developed with the assistance of a medical research librarian with details described in a previously published protocol [22]. The full version of the search strategy for both databases is provided in additional files (see Additional files 1 and 2). This strategy included searching of all study references to identify any other relevant articles not captured in the original search. Duplicate studies were removed using digital object identifiers and manually comparing titles, authors, publication dates, and article metadata. All identified studies were screened individually by two reviewers for inclusion, and disagreement was resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Two reviewers evaluated all the included studies to extract relevant information from the studies and resolved ambiguities by discussion. For each study, the following information was extracted: (a) number of reported clinical trials, (b) number of published articles, (c) trial registries used, (d) the study purpose (such as publication bias, outcome reporting bias, or assessing the publication rate of registered trials), (e) application domain (any constraints such as journal lists, conditions, or specialties), (f) processes for identifying links, and (g) proportions of links found using each process.

The processes used to identify links were categorised as one of three types: automatic, inferred, and inquired. Automatic links were defined by any process that used the unique registry identifier to reconcile the link into or from a bibliographic database without the need for a search or inquiry. This included searching PubMed for registry identifiers to find published articles in cohorts of registry entries or using identifiers in the metadata, abstract, or full text of published articles to find registry entries in cohorts of published articles. Inferred links were defined by any manual processes in which investigators searched for matches across databases using characteristics of the trial such as the names of the investigators, titles, and acronyms associated with the trial, location, sample size, or the population, intervention, or measurable outcome information to find a match in a bibliographic database or trial registry. Inquired links were defined by any manual process where the study authors attempted to contact the investigators or authors of a trial to request or confirm the presence or absence of a registry entry or a published article for each included trial.

Data synthesis and analysis

We examined the proportions of links that were identified through each of these three processes. Using the publication year of the studies that used both automatic and manual processes, we applied linear regression to determine whether the utility of the automatic processes—the proportion that were found automatically compared to the proportion that required manual processes—had increased over time. We did not undertake a pooled analysis of the utility of automatic links because many studies did not specify proportions found by each process used and because of the heterogeneity in the study designs. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

The protocol for this systematic review was published in 2016 [22] (see Additional file 3). We did not register the systematic review with PROSPERO because it does not directly examine at least one outcome of direct patient or clinical relevance.

Results

The initial search returned 11,986 results (after non-English articles were excluded), which produced 9486 articles after de-duplication (Fig. 1) [25]. A set of 348 studies remained after screening titles and abstracts, and of these, 81 studies were included in the review. One study considered links from both cohorts of registry entries and published articles [15, 26], for a total of 82 analyses. Excluded studies included conference abstracts, studies for which information about the proportions of registry entries or published articles that were identified was ambiguous [27–29] and studies that considered reporting biases but could not be included because the linking was atypical or there was no linking performed [30–33]. Some studies were excluded because they did not measure links between trial registries and bibliographic databases and, instead, considered links to or from other source of clinical trial information. These included links to or from protocols [34–37], conference or meeting abstracts [38–42], internal company documents [17], Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documents or new drug approvals [43–47], or other databases of published articles [48, 49].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection for a search and screening process that resulted in the inclusion of 81 studies

Studies identifying published articles from cohorts of registry entries

We identified 43 studies that examined links to published articles from registries, typically with the aim of examining publication bias or outcome reporting bias (Table 1). The application domains varied by types of studies (e.g., terminated and withdrawn trials [50, 51], trials funded by specific organisations or from certain countries [52, 53]), and by specialty and condition (e.g., paediatric or surgical trials [54, 55]). The most commonly studied registry was ClinicalTrials.gov only (35 studies), followed by some or all the registries of the WHO ICTRP (8 studies). The most commonly examined bibliographic databases were PubMed alone (22 studies), or Embase in combination with PubMed or other bibliographic databases (20 studies). The studies included cohorts of registry entries that ranged in size from 34 to 8907 (median 305) entries. The median proportion of registry entries for which published articles were found was 47%, and these proportions ranged from 4% (2 published articles in a cohort of 46 registry entries) to 76% (47 published articles in a cohort of 62 registry entries).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 43 analyses identifying published articles from cohorts of trial registry entries

| Study | Registry entry cohort | Published articles found | Trial registries included | Study purpose | Study publication year | Application domain | Proportion of links by process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartung [70] | 305 | 110 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To determine consistency between registered trials and their publication | 2014 | Phase III or IV trials | Automatic = 95 Inferred = 15 |

| Ross [51] | 677 | 315 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess the publication of registered trials in ClinicalTrials.gov | 2009 | Completed trials of phase II or higher | Automatic = 96 Inferred = 215 Inquired = 4 (contact = 117, responded = 44, published = 4) |

| Bourgeois [71] | 546 | 362 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To determine whether funding source of these trials is associated with favorable published outcomes | 2010 | Anticholesteremics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, proton-pump inhibitors, and vasodilators | Inferred = unknown Inquired = unknown |

| Liu [72] | 443 | 156 | ANZCTR, ISRCTN, ChiCTR, IRCT, DRKS, NTR, JPRN, SLCTR, CTRI, PACTR, Clinicaltrials.gov. | Publication rate of Chinese Trials in WHO Registries | 2010 | Trials sponsored by China | Automatic = 103 Inferred = 40 Inquired = 13 (contact = 54, responded = all, published = 1) |

| Prenner [73] | 64 | 35 | Clinicaltrials.gov | To evaluate the rate of publication of registered clinical trials concerning age-related macular degeneration | 2009 | Muscular degeneration | Automatic = 8 Inferred = 27 |

| Wildt [74] | 105 | 66 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To evaluate the adequacy of reporting of protocols for on diseases of the digestive system | 2011 | Gastrointestinal diseases | Inferred = 66 |

| Gandhi [75] | 37 | 20 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To compare the published orthopaedic trauma trials following registration in ClinicalTrials.gov | 2011 | Orthopaedic trauma | Automatic and Inferred = unknown |

| Ross [53] | 635 | 432 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To review patterns of publication of clinical trials funded by NIH in peer reviewed biomedical journals | 2012 | NIH-funded trials in biomedical journals | Automatic and Inferred = unknown |

| Shamliyan [76] | 758 | 212 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To examine registration, completeness and publication of children studies | 2012 | Children studies funded by NIH | Inferred = 212 |

| Vawdrey [77] | 62 | 47 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To measure the rate of non-publication and assess possible publication bias in clinical trials of electronic health records | 2012 | Electronic health record registered in clinicaltrials.gov | Automatic, inferred, and inquired = unknown |

| Chapman [55] | 314 | 208 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To determine the rate of early discontinuation and non-publication of RCTs | 2014 | Surgery | Inferred = 192 Inquired = 16 (contact = 101, responded = 25, published = 16) |

| Liu [52] | 505 | 115 | All 14 registries in ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov | To estimate bias risk and outcome-reporting bias in RCTs of traditional Chinese medicine | 2013 | Traditional Chinese medicines | Unknown |

| van de Wetering [26] | 599 | 312 | NTR | To evaluate the reporting of trial registration numbers in biomedical publications | 2012 | Biomedical publications | Automatic and inferred = unknown Inquired = 0 (contact = 42, responded = 9, published = 0) |

| Huser [15] | 8907 | 885 | ClinicalTrials.gov | Linking ClinicalTrials.gov with PubMed | 2013 | Interventional phase II or higher clinical trials | Automatic = 885 |

| Stockmann [78] | 108 | 65 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To evaluate the publication patterns of obstetric studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov | 2014 | Obstetric studies | Automatic = 45 Inferred = 20 |

| Jones [79] | 585 | 414 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To estimate the frequency with which results of large randomized clinical trials registered with ClinicalTrials.gov are not available to the public | 2013 | Interventional RCTs with more than one arm | Automatic and inferred = unknown Inquired = 4 |

| Riveros [80] | 594 | 297 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess timing and completeness of trial results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in journals | 2013 | Interventional studies of phase III and IV | Unknown |

| Korevaar [81] | 418 | 224 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess publication and reporting of test accuracy studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov | 2014 | Test accuracy studies | Automatic = 154 Inferred = 64 Inquired = 6 (contact = 175, responded = 119, published = 6) |

| Munch [82] | 391 | 118 | ICTRP, ClinicalTrials.gov | To analyse the perils and pitfalls of constructing a global open-access database of registered analgesic clinical trials | 2014 | Analgesic clinical trials | Inferred = 118 |

| Hill [54] | 90 | 66 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess the characteristics of paediatric cardiovascular clinical trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov | 2014 | Pediatric cardiovascular clinical trials | Unknown |

| Khan [83] | 143 | 95 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To examine characteristics associated with the publication and timeliness of publication of RCTs of treatment of rheumatoid arthritis | 2014 | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Automatic and inferred = unknown Inquired = 1 (contact = 58, responded = 28, published = 1) |

| Su [84] | 239 | 88 | All 14 registries in ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov | Outcome reporting bias | 2015 | Acupuncture | Automatic and inferred = unknown |

| Hakala [85] | 177 | 102 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To quantify the proportion of trials for unsuccessfully licensed drugs that are not published | 2015 | Stalled drugs | Automatic = unknown Inferred = unknown Inquired = 0 (emails or calls = 42, responded = 9, published = 0) |

| Pranic [50] | 81 | 21 | ClinicalTrials.gov | Outcome reporting bias | 2016 | Completed RCTs | Inferred = 21 |

| Tang [86] | 300 | 222 | ClinicalTrials.gov | Outcome reporting bias | 2015 | Random sample of phase II or IV trials | Automatic and inferred = unknown |

| Boccia [87] | 1109 | 120 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess the status of registration of observational studies | 2015 | Cancer | Inferred = 120 |

| Saito [88] | 400 | 229 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To determine publication rates of completed US trials | 2014 | Interventional studies | Automatic = 126 Inferred = 103 |

| Son [89] | 161 | 62 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess whether there is publication bias in industry funded clinical trials of degenerative diseases of the spine | 2015 | Diseases of the spine | Inferred = 62 |

| Baudart [90] | 489 | 189 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To evaluate the publication rate of observational studies for intervention | 2016 | Observational studies with safety outcomes | Automatic = 75 Inferred = 99 Inquired = 15 (contact = 241, responded = 52, published = 15) |

| Chahal [91] | 34 | 20 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To determine publication rates of RCTs in sports medicine | 2012 | Sports medicine | Automatic and Inferred = unknown |

| Manzoli [92] | 355 | 176 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP, ANZCTR, ChiCTR, Current Control Trails, Clinical Study Register or Indian | To evaluate the extent of non-publication or delayed publication of registered RCTs on vaccines | 2014 | Vaccines | Automatic = 132 Inferred = 44 Inquired = 0, (contact = 24, responded = 0, published = unknown) |

| Lebensburger [93] | 147 | 52 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To analyse ClinicalTrials.gov for registered sickle cell trials | 2015 | Sickle cells | Automatic = 28 Inferred = 24 |

| Smith [94] | 101 | 25 | ClinicalTrials.gov | Outcome reporting bias | 2012 | Arthroplasty | Automatic = 10 Inferred = 15 |

| Guo [95] | 35 | 11 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To estimate patterns of publication of clinical trials of endometriosis registered in ClinicalTrials.gov | 2013 | Endometriosis | Inquired = 8 Inferred = 3 |

| Tsikkinis [96] | 333 | 141 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To identify all phase III prostate cancer trials in ClinicalTrials.gov with pending results | 2015 | Prostate cancer | Inferred = 141 |

| Chen [97] | 4347 | 2458 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess publication rate and reporting of results for completed trials | 2016 | Interventional clinical trials | Automatic and inferred = unknown |

| Ramsey [98] | 2028 | 357 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess the proportion of registered trials that are published | 2008 | Oncology | Automatic = 357 |

| Hurley [99] | 142 | 62 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess the delayed publication of clinical trials | 2012 | Cystic fibrosis | Inferred = 59 Inquired = 3 (contact = 83, responded = 29, published = 3) |

| Ioannidis [100] | 73 | 21 | Cochrane Controlled Clinical Trial Register, ISRCTN, ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP, GSK Clinical Study Register, and Indian, ANZCTR, and Chinese Clinical Trial Registries) | To assess publication delay | 2011 | Influenza A (H1N1) vaccination | Unknown |

| Ohnmeiss [101] | 72 | 28 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To assess the publication of the studies registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. | 2015 | Spine studies | Automatic and inferred = unknown |

| Gopal [102] | 6251 | 818 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To evaluated the rate of compliance with the FDA mandatory results reporting in clinicaltrials.gov | 2012 | Interventional studies | Automatic = 818 |

| Lampert [103] | 76 | 40 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To determine selective outcome reporting and delay of publication | 2015 | Epilepsy | Automatic = 32 Inferred = 7 Inquired = 1 |

| Gandhi [104] | 46 | 2 | ISRCTN, ClinicalTrials.gov, ANZCTR | To determine the extent to which ongoing and future RCTs in diabetes will ascertain patient-important outcomes | 2008 | Diabetes | Unknown |

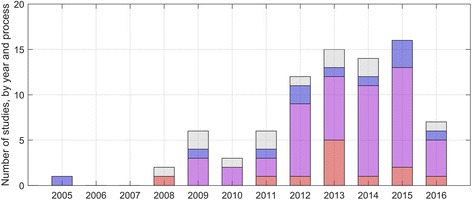

The processes used to identify links between clinical trial registries and published articles varied across the set of studies (Figs. 2 and 3). The most common process was to use a combination of automatic and manual processes (24/43, 56%), followed by manual processes only (11/43, 26%), and automatic processes only (3/43, 7%). There were five studies for which the process for identifying published articles was not clear or not provided.

Fig. 2.

The processes used to identify links in 81 included studies, including studies that examined automatic links only (red), both automatic and manual processes (purple), manual processes only (blue), and studies that did not report the processes used (grey)

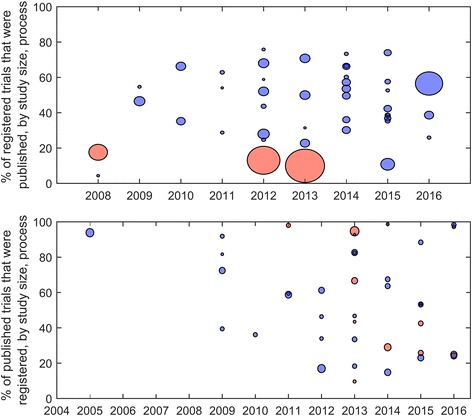

Fig. 3.

The proportions of published articles identified in cohorts of registry entries (top, 43 studies, ranging from 34 to 8907 registry entries) and the proportions of registry entries found in cohorts of published articles (bottom, 39 studies, ranging from 54 to 698 articles), with studies that only considered automatic links (red) and all other studies (blue). The circle areas are proportional to the study size

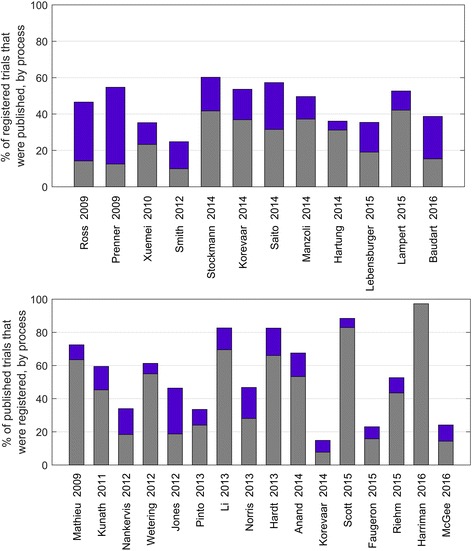

Of the 24 studies that looked for published articles among a cohort of registry entries and used both manual and automatic processes, 12 studies specified the number of published articles identified via each process (Fig. 4). Among these studies, automatic links were used to identify between 13 and 42% (median 23%) of the published articles, and manual processes were used to find a further 5–42% (median 17%) articles that were not available via automatic links.

Fig. 4.

The proportions of published articles found in cohorts of registry entries (12 studies, top) and the proportions of registry entries found in cohorts of published articles (16 studies, bottom), by automatic links (grey) and manual processes (blue)

We found no evidence of a change in the overall proportion of publications that could be found via automatic links. A linear regression over the 12 studies—using the publication year as the independent variable—indicated no significant trend in the proportion of available links that can be identified by automatic processes (R 2 = 0.02, p = 0.36, β = 1.28% increase per year).

Studies identifying registry entries from cohorts of publications

There were 39 studies that considered cohorts of publications and identified associated registry entries in one or more of the WHO ICTRP clinical trial registries (Table 2). These studies included a range of 51–698 (median 181) published articles. These studies also covered a range of application domains, varying by the selection of journal, discipline, or study design [56–62]. The most commonly used bibliographic database was PubMed alone (19 studies), followed by PubMed in combination with other bibliographic databases (7 studies). To identify registrations, the studies most commonly searched ClinicalTrials.gov in combination with other registries (25 studies), followed by all trial registries included in the WHO ICTRP (9 studies). The median proportion of registry entries that were identified from cohorts of published articles was 54%, ranging from 10% (8 registrations from a cohort of 83 published articles) to 99% (75 registrations from a cohort of 76 published articles).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 39 analyses identifying trial registry entries from cohorts of published articles

| Study | Published article cohort | Registry entries found | Trial registries included | Study purpose | Study publication year | Application domain | Proportion of links by process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathieu [59] | 234 | 323 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ICTRP, national register based on country of first author | Outcome reporting bias | 2009 | Cardiology, rheumatology, gastroenterology | Automatic = 205 Inferred = 6 Inquired = 23 |

| Chowers [105] | 49 | 60 | Unknown | Outcome reporting bias | 2009 | Anti-retroviral therapy | Unknown |

| Rasmussen [60] | 54 | 137 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ICTRP, NCI-PDQ | To determine association of trial registration with the results and conclusions of published trials | 2009 | Oncology drugs | Inferred = 54 |

| Kunath [58] | 63 | 106 | ICTRP | To observe trial registration in urology journals | 2011 | Urology | Automatic = 48 Inferred = 15 |

| Ewart [56] | 135 | 124 | ISRCTN, ClinicalTrials.gov, ANZCTR, EU-CTR, National Research Register | Outcome reporting bias | 2009 | RCTs in five high-impact factor journals | Unknown |

| You [106] | 215 | 366 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN | Outcome reporting bias | 2011 | Oncology drugs | Unknown |

| Reveiz [109] | 89 | 526 | ICTRP | Outcome reporting bias | 2012 | RCT from Latin America and Caribbean | Unknown |

| Nankervis [108] | 37 | 109 | ICTRP | Outcome reporting bias | 2012 | Eczema treatment | Automatic = 20 Inferred = 17 |

| Pinto [107] | 67 | 200 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ANZCTR, national register based on country of first author | Completeness of clinical trial registration and the extent of selective reporting of outcomes in published trials | 2013 | Physical therapy | Automatic = 48 Inferred = 2 Inquired = 17 |

| van de Wetering [26] | 185 | 302 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ICTRP, national register based on country of first author | To determine reporting of trial registration numbers in biomedical publications | 2012 | RCT from core clinical journals | Automatic = 166 Inquired = 19 (contact = 136, responded = 51, published = 19) |

| Hannink [110] | 218 | 327 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ANZCTR and others | Outcome reporting bias | 2013 | Surgical interventions | Automatic = 218 |

| Huser [16] | 661 | 698 | ClinicalTrials.gov.gov, ISRCTN | Evaluating adherence to ICMJE policy of mandatory and timely clinical trial registration | 2013 | Trials published in five ICMJE journals | Automatic = 661 |

| Rosenthal [111] | 51 | 55 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ANZCTR, ChiCTR, UMIN | Outcome reporting bias | 2013 | Surgery | Automatic, inferred, and inquired = unknown |

| Hopewell [112] | 30 | 69 | Unknown | To observe reporting characteristics of non-primary publications of results of RCTs | 2013 | RCTs from National Library of Medicine’s set of 121 core clinical journals | Automatic = 30 |

| Babu [113] | 121 | 417 | Unknown | To observe clinical trial registration in physical therapy journals | 2014 | Physical therapy journals | Automatic = 121 |

| Lee [114] | 8 | 83 | Unknown | Assessment of compliance of randomized controlled trials in trauma surgery with the CONSORT statement | 2013 | Trauma surgery | Automatic = 8 |

| Li [115] | 252 | 305 | ClinicalTrials.gov, Current Controlled Trials, NTR, ANZCTR, UMIN CTR | Outcome reporting bias | 2013 | Gastroenterology and herpetology | Automatic = 212 Inferred = 40 |

| Norris [116] | 50 | 107 | ICTRP | To determine selective outcome reporting | 2013 | Pharmacotherapy | Automatic = 30 Inferred = 20 |

| Hardt [117] | 85 | 103 | ICTRP(ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, EU-CTR, NTR, ANZCTR, DRKS, JPRNUMIN, ChiCTR, CTRI), Belgian register | To determine whether the results of registered surgical RCTs are published in journals requiring registration | 2013 | Ten highest rank surgery journals | Automatic = 68 Inferred = 17 |

| Anand [118] | 133 | 197 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ANZCTR | To determine the registration and design alterations of clinical trials in clinical care | 2014 | RCT in clinical care medicine | Automatic = 105 Inferred = 28 |

| Mann [119] | 140 | 220 | ICTRP | To assess the registration status of RCTs and analyse the correspondence of registered outcomes with published outcomes | 2014 | Clinical geriatrics | Unknown |

| Walker [120] | 75 | 76 | ISRCTN, ClinicalTrials.gov, national register based on country of first author | Outcome reporting bias | 2014 | RCTs published in British Medical Journal and the Journal of American Medical Association | Automatic and inferred = unknown |

| Dekkers [121] | 29 | 54 | ICTRP | To compare non-inferiority margins defined in study protocols and trial registry records with margins reported in subsequent publications | 2015 | Non-inferiority trials submitted 2001–2005 to ethics committees in Switzerland and Netherlands | Automatic and inferred = unknown |

| Østervig [122] | 85 | 200 | ISRCTN, IRCT, EU-CTR, ChiCTR, CRiS, UMIN CTR, ClinicalTrials.gov | To check registration of randomized clinical trials | 2015 | Trials in Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica | Automatic = 85 |

| Scott [62] | 160 | 181 | ISRCTN, NTR, ANZCTR, ClinicalTrials.gov, national register based on country of first author | Selective outcome reporting | 2015 | Psychiatry journals | Automatic = 150 Inferred = 6 Inquired = 4 |

| De Oliveira [123] | 107 | 201 | ISRCTN, ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP | Outcome reporting bias | 2015 | Anaesthesiology | Automatic, inferred, and inquired = unknown |

| Rayhill [61] | 58 | 225 | ClinicalTrials.gov and others | To assess the registration status of RCTs and analyse the correspondence of registered outcomes with published outcomes | 2015 | Core headache medicine journals | Automatic = 58 |

| Dal-Ré [124] | 175 | 178 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ANZCTR, NTR, EU-CTR, CTRI, DRKS | To evaluate adherence to ICMJE policy on prospective trial registration | 2016 | Trials in high-impact journals | Unknown |

| Reveiz [125] | 52 | 144 | Registered in any international clinical trial registry | To evaluate the influence of trial registration on reporting quality of RCTs | 2010 | Highest rank journals | Unknown |

| Rongen [126] | 90 | 362 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ANZCTR, NTR and others | Outcome reporting bias | 2016 | Orthopedic surgical interventions | Automatic = 90 |

| Harriman [57] | 105 | 108 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ANZCTR, UMIN CTR, NTR, ChiCTR, IRCT | To assess trial registration, analysis of prospective versus retrospective registration | 2016 | Clinical trials published in the BMC series | Automatic = 105 Inquired = 0 |

| Vera-Badillo [129] | 30 | 164 | ClinicalTrials.gov | Outcome reporting bias | 2013 | Breast cancer | Automatic and inferred = unknown |

| McGee [128] | 74 | 307 | ICTRP | To determine whether trial is registered and declared registration in the publication | 2016 | Kidney transplantation | Automatic = 44 Inferred = 30 |

| Huić [127] | 149 | 152 | ClinicalTrials.gov | To determine completeness and outcome reporting bias | 2011 | RCTs published in ICMJE journals | Automatic = 149 |

| Chan [34] | 519 | 553 | Unknown | Outcome reporting bias | 2005 | RCTs indexed in PubMed | Inferred and inquired = unknown |

| Korevaar [130] | 52 | 351 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, national register based on country of first author | To identify the proportion of articles for which the corresponding study had been registered | 2014 | Test accuracy studies | Automatic = 27 Inferred = 11 Inquired = 14 (contact = 324, responded = 187, published = 14) |

| Jones [131] | 57 | 123 | ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, ICTRP, national register based on country of first author | Outcome reporting bias | 2012 | Emergency | Automatic = 23 Inferred = 34 |

| Smaïl-Faugeron [132] | 73 | 317 | ICTRP | To assess the registration rate of RCTs | 2015 | Oral health | Automatic = 50 Inferred = 23 |

| Riehm [133] | 40 | 76 | ISRCTN, ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP | Outcome reporting bias | 2015 | Psychosomatic and behavioral health | Automatic = 33 Inferred = 7 |

The processes used to identify links between clinical trial registries and published articles varied across the set of studies (Figs. 2 and 3). The most common process was to use a combination of automatic and manual processes (21/39, 54%), followed by automatic processes only (9/39, 23%), and manual processes only (2/39, 5%). There were 7 studies for which the processes used to identify registry entries were not clear or not provided.

Of the 21 studies that looked for registry entries among a cohort of published articles and used both manual and automatic processes, 16 reported the number of registry entries found using each process (Fig. 4). Among these studies, automatic links identified between 8 and 97% (median 49%) of registry entries and the manual processes identified between 0 and 28% (median 10%) additional entries.

We found no evidence of a change in the overall proportion of published articles for which registry entries could be found via automatic links. A linear regression over the 16 studies—using the publication year as the independent variable—indicated no significant trend in the proportion of links that can be identified via automatic processes (R 2 = 0.01, p = 0.73, β = 1.40% increase per year).

Discussion

In this systematic review, we found that investigators use both automatic and manual processes to link registry entries and publications and that automatic links could be used to identify some but not all links between registry entries and published articles. We found no evidence that the utility of automatic processes had increased over time.

To the best of our knowledge, no other systematic review has examined the utility of automatic links between trial registries and bibliographic databases. Previous studies that examined the availability of automatic links provided a broad analysis of automatic links made available through ClinicalTrials.gov and PubMed but did not systematically evaluate the proportion of links that could additionally be resolved using manual processes [15, 16, 63]. Other systematic reviews have examined reporting biases as a topic and included subsets of the studies we included [14, 64], but focused on publication rates and the completeness and consistency of outcome reporting, which we did not evaluate here. Our review adds to this area of research by compiling information about a broader group of studies and synthesising what is known about the utility of automatic links, and the need for supplementing automatic processes with manual processes, in studies that rely on links between trial registries and bibliographic databases.

Implications

Our results indicate that automatic links alone are a useful but not sufficient process for measuring rates of registration and publication or associated biases. Relying on automatic links to draw conclusions about the rate of non-publication will likely over-estimate the rate of non-publication. When aiming to monitor compliance with prospective registration of clinical trials, or monitoring publication practices and patterns, the limits of automatic links should be considered.

In general, the proportion of links identified by automatic processes was lower in studies that started with a cohort of registry entries and aimed to identify published articles, compared to studies that started with a cohort of published articles, and aimed to identify registrations. This may be a consequence of journals that have not yet established standards for registration [65] or have not implemented standards for incorporating registry identifiers in the information they pass to bibliographic databases.

The results also have implications for systematic reviews. Systematic review technologies for automating or supporting reviewers rarely consider information from clinical trial registries to improve the searching or screening processes [66] or the prioritisation or scheduling of systematic review updates. Because systematic reviews are already time-consuming [67, 68], the need for additional manual effort in the linking of trial registry entries with their published results may have hindered the development of tools based on this linkage. Areas for development include processes where systematic reviewers compare published reports with information in a registry or use trial registries to identify trials not found in bibliographic databases. By removing these barriers, machine-readable information linking all published studies with all registry entries may provide the catalyst for the increased use of registries in the searching, screening, and prioritising of systematic reviews.

Recommendations

We recommend continued pressure to ensure that journals and publishers adhere to standards of reporting that require unique trial identifiers to be specified in the abstract of the article and reported as part of the metadata provided to bibliographic databases. Trial investigators should also be encouraged to update registry entries with links to published results when journals do not provide the information to bibliographic databases. As we move into an era where the structured reporting of clinical trial results and individual participant data become the standard for responsible clinical trial reporting [69], the inability to automatically identify all sources of information about a clinical trial hinders our ability to reuse and synthesise results across trials. Given the number of extra links that could be identified by examining the full text of articles, we also recommend that journals ensure that clinical trial identifiers are included in the abstract or metadata provided to bibliographic databases.

We additionally recommend a standardised method for identifying links between registry entries and published articles that, for the time being, includes manual validation and checking and avoids drawing conclusions based only on automatic links. A standardised method should include details about what elements of a registry entry should be used to search for published articles and a standard definition for what constitutes published results. Standard reporting for these studies should include the number of registry entries for which searches were performed, the proportion that were identified by automatic links, by inference or by inquiry, and the full details of the dates of trial completion and the length of follow-up. Presenting studies in terms of the time to publication rather than the presence or absence of publication would make a greater proportion of the studies comparable and amenable to meta-analysis.

Limitations

There are two limitations to this review. First, the exclusion of studies for which there was no English language version available meant that we may have missed some studies examining WHO ICTRP registries from countries where English is not the primary language. Second, we used the publication year of the studies as a proxy for estimating changes in the proportions of links identified by each process without considering the period of study that each of the studies covered. This was necessary because a substantial proportion of studies did not report the range and distribution of publication and registration dates in the cohorts they examined, and this may have influenced our analysis of the trends in the utility of the automatic processes.

Conclusions

In this systematic review, we have quantified the use and utility of the processes that are used to link trial registries to bibliographic databases. The results indicate that manual processes are still used extensively and that the gap between what can be identified via automatic processes and what must be identified via manual processes persists. Future improvements in the quality of automatic linking between clinical trial registries and bibliographic databases should come from continued pressure on journals to enforce policies and practices to consistently include registry identifiers in published reports.

Additional files

Search strategy for PubMed. Search strategy for MEDLINE via PubMed. (PDF 259 kb)

Search strategy for Embase. Search strategy for Embase via Ovid. (PDF 309 kb)

PRISMA checklist. PRISMA Checklists with manuscript page number reference. (PDF 277 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

RB is supported by a Macquarie University Postgraduate Scholarship. AD and FB report funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R03HS024798).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files 1, 2, and 3.

Authors’ contributions

RB and AD drafted the manuscript, conducted the review, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version. FB critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ICTRP

International Clinical Trial Registry Platform

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0518-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Rabia Bashir, Email: rabia.bashir@students.mq.edu.au.

Florence T. Bourgeois, Email: Florence.Bourgeois@childrens.harvard.edu

Adam G. Dunn, Email: adam.dunn@mq.edu.au

References

- 1.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, Kotzin S, Laine C, Marusic A, Overbeke AJP. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1250–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickersin K, Chan S, Chalmers TC, Sacks HS, Smith H. Publication bias and clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1987;8(4):343–53. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(87)90155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickersin K, Rennie D. Registering clinical trials. JAMA. 2003;290(4):516–523. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCray AT. Better access to information about clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(8):609–614. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meinert CL. Toward prospective registration of clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1988;9(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simes RJ. Publication bias: the case for an international registry of clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(10):1529–1541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.10.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Califf R, Zarin D, Kramer J, Sherman R, Aberle L, Tasneem A. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1838–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dwan K, Altman DG, Clarke M, Gamble C, Higgins JP, Sterne JA, Williamson PR, Kirkham JJ. Evidence for the selective reporting of analyses and discrepancies in clinical trials: a systematic review of cohort studies of clinical trials. PLoS Med. 2014;11(6):e1001666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prayle AP, Hurley MN, Smyth AR. Compliance with mandatory reporting of clinical trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2012;344:d7373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tse T, Williams RJ, Zarin DA. Update on registration of clinical trials in ClinicalTrials.gov. Chest. 2009;136(1):304–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarin DA, Tse T, Ide NC. Trial registration at ClinicalTrials.gov between May and October 2005. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(26):2779–2787. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooft L, Korevaar DA, Molenaar N, Bossuyt PM, Scholten RJ. Endorsement of ICMJE’s Clinical Trial Registration Policy: a survey among journal editors. Neth J Med. 2014;72(7):349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.No R: 536/2014 of the European Parliament and the Council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20. EC Official Journal of the European Union, L 2014, 158(27.5).

- 14.Dwan K, Gamble C, Williamson PR, Kirkham JJ. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias—an updated review. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e66844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huser V, Cimino JJ. Linking ClinicalTrials. gov and PubMed to track results of interventional human clinical trials. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huser V, Cimino JJ. Evaluating adherence to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ policy of mandatory, timely clinical trial registration. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(e1):e169–e174. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CW, Keil LG, Weaver MA, Platts-Mills TF. Clinical trials registries are under-utilized in the conduct of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional analysis. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroll JB, Bero L, Gøtzsche PC. Searching for unpublished data for Cochrane reviews: cross-sectional study. BMJ. 2013;346:f2231. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe N, Gøtzsche PC, Bero L. Strategies for obtaining unpublished drug trial data: a qualitative interview study. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baudard M, Yavchitz A, Ravaud P, Perrodeau E, Boutron I. Impact of searching clinical trial registries in systematic reviews of pharmaceutical treatments: methodological systematic review and reanalysis of meta-analyses. BMJ. 2017;356:j448. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmucker CM, Blümle A, Schell LK, Schwarzer G, Oeller P, Cabrera L, von Elm E, Briel M, Meerpohl JJ, on behalf of the Oc Systematic review finds that study data not published in full text articles have unclear impact on meta-analyses results in medical research. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0176210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bashir R, Dunn AG. Systematic review protocol assessing the processes for linking clinical trial registries and their published results. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e013048. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bramer WM, Giustini D, Kramer BM. Comparing the coverage, recall, and precision of searches for 120 systematic reviews in Embase, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar: a prospective study. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preston L, Carroll C, Gardois P, Paisley S, Kaltenthaler E. Improving search efficiency for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy: an exploratory study to assess the viability of limiting to MEDLINE, EMBASE and reference checking. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van de Wetering F, Scholten R, Haring T, Clarke M, Hooft L. Trial registration numbers are underreported in biomedical publications. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrasco M, Volkmar FR, Bloch MH. Pharmacologic treatment of repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders: evidence of publication bias. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1301–e1310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nowbar AN, Mielewczik M, Karavassilis M, Dehbi H-M, Shun-Shin MJ, Jones S, Howard JP, Cole GD, Francis DP. Discrepancies in autologous bone marrow stem cell trials and enhancement of ejection fraction (DAMASCENE): weighted regression and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2688. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(3):252–260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adewuyi TE, MacLennan G, Cook JA. Non-compliance with randomised allocation and missing outcome data in randomised controlled trials evaluating surgical interventions: a systematic review. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1364-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourgeois FT, Murthy S, Mandl KD. Comparative effectiveness research: an empirical study of trials registered in ClinicalTrials. gov. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole GD, Nowbar AN, Mielewczik M, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis DP. Frequency of discrepancies in retracted clinical trial reports versus unretracted reports: blinded case-control study. BMJ. 2015;351:h4708. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshimoto Y. Publication bias in neurosurgery: lessons from series of unruptured aneurysms. Acta Neurochir. 2003;145(1):45–48. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-1036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan A-W, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2457–2465. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasenda B, Von Elm E, You J, Blümle A, Tomonaga Y, Saccilotto R, Amstutz A, Bengough T, Meerpohl JJ, Stegert M. Prevalence, characteristics, and publication of discontinued randomized trials. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1045–1052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smyth R, Kirkham J, Jacoby A, Altman D, Gamble C, Williamson P. Frequency and reasons for outcome reporting bias in clinical trials: interviews with trialists. BMJ. 2011;342:c7153. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tharyan P, George AT, Kirubakaran R, Barnabas JP. Reporting of methods was better in the Clinical Trials Registry-India than in Indian journal publications. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(1):10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris P, Takeda A, Loveman E, Hartwell D. Time to full publication of studies of anticancer drugs for breast cancer, and the potential for publication bias. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2010;26(01):110–116. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309990778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massey PR, Wang R, Prasad V, Bates SE, Fojo T. Assessing the eventual publication of clinical trial abstracts submitted to a large annual oncology meeting. Oncologist. 2016;21(3):261–268. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polyzos NP, Valachis A, Patavoukas E, Papanikolaou EG, Messinis IE, Tarlatzis BC, Devroey P. Publication bias in reproductive medicine: from the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology annual meeting to publication. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1371–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saeed M, Paulson K, Lambert P, Szwajcer D, Seftel M. Publication bias in blood and marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(6):930–934. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scherer RW, Huynh L, Ervin A-M, Dickersin K. Using ClinicalTrials. gov to supplement information in ophthalmology conference abstracts about trial outcomes: a comparison study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang L, Dhruva SS, Chu J, Bero LA, Redberg RF. Selective reporting in trials of high risk cardiovascular devices: cross sectional comparison between premarket approval summaries and published reports. BMJ. 2015;350:h2613. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller JE, Korn D, Ross JS. Clinical trial registration, reporting, publication and FDAAA compliance: a cross-sectional analysis and ranking of new drugs approved by the FDA in 2012. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e009758. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreno SG, Sutton AJ, Turner EH, Abrams KR, Cooper NJ, Palmer TM, Ades A. Novel methods to deal with publication biases: secondary analysis of antidepressant trials in the FDA trial registry database and related journal publications. BMJ. 2009;339:b2981. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner EH, Knoepflmacher D, Shapley L. Publication bias in antipsychotic trials: an analysis of efficacy comparing the published literature to the US Food and Drug Administration database. PLoS Med. 2012;9(3):e1001189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Withycombe B, Ovenell M, Meeker A, Ahmed SM, Hartung DM. Timing of pivotal clinical trial results reporting for newly approved medications varied by reporting source. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Mitchell AP, Hirsch BR, Abernethy AP. Lack of timely accrual information in oncology clinical trials: a cross-sectional analysis. Trials. 2014;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prasad V, Goldstein JA. Clinical trial spots for cancer patients by tumour type: the cancer trials portfolio at clinicaltrials. gov. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(17):2718–2723. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pranić S, Marušić A. Changes to registration elements and results in a cohort of Clinicaltrials. gov trials were not reflected in published articles. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;70:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Hines EM, Nissen SE, Krumholz HM. Trial publication after registration in ClinicalTrials. gov: a cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(9):e1000144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu J-P, Han M, Li X-X, Mu Y-J, Lewith G, Wang Y-Y, Witt CM, Yang G-Y, Manheimer E, Snellingen T. Prospective registration, bias risk and outcome-reporting bias in randomised clinical trials of traditional Chinese medicine: an empirical methodological study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e002968. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ross JS, Tse T, Zarin DA, Xu H, Zhou L, Krumholz HM. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials. gov: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:d7292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hill KD, Chiswell K, Califf RM, Pearson G, Li JS. Characteristics of pediatric cardiovascular clinical trials registered on ClinicalTrials. gov. Am Heart J. 2014;167(6):921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chapman SJ, Shelton B, Mahmood H, Fitzgerald JE, Harrison EM, Bhangu A. Discontinuation and non-publication of surgical randomised controlled trials: observational study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ewart R, Lausen H, Millian N. Undisclosed changes in outcomes in randomized controlled trials: an observational study. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(6):542–546. doi: 10.1370/afm.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harriman SL, Patel J. When are clinical trials registered? An analysis of prospective versus retrospective registration. Trials. 2016;17(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kunath F, Grobe HR, Keck B, Rücker G, Wullich B, Antes G, Meerpohl JJ. Do urology journals enforce trial registration? A cross-sectional study of published trials. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000430. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mathieu S, Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Ravaud P. Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2009;302(9):977–984. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rasmussen N, Lee K, Bero L. Association of trial registration with the results and conclusions of published trials of new oncology drugs. Trials. 2009;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rayhill ML, Sharon R, Burch R, Loder E. Registration status and outcome reporting of trials published in core headache medicine journals. Neurology. 2015;85(20):1789–1794. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott A, Rucklidge JJ, Mulder RT. Is mandatory prospective trial registration working to prevent publication of unregistered trials and selective outcome reporting? An observational study of five psychiatry journals that mandate prospective clinical trial registration. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0133718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huser V. Cimino JJ. Precision and negative predictive value of links between ClinicalTrials. gov and PubMed. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:400–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan A-W, Cronin E, Decullier E, Easterbrook PJ, Von Elm E, Gamble C. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wager E, Williams P. “Hardly worth the effort”? Medical journals’ policies and their editors’ and publishers’ views on trial registration and publication bias: quantitative and qualitative study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsafnat G, Glasziou P, Choong M, Dunn A, Galgani F, Coiera E. Systematic review automation technologies. Syst rev. 2014;3(1):74. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sampson M, Shojania KG, Garritty C, Horsley T, Ocampo M, Moher D. Systematic reviews can be produced and published faster. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(6):531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, Ji J, Doucette S, Moher D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(4):224–233. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-4-200708210-00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zarin DA, Tse T. Sharing individual participant data (IPD) within the context of the trial reporting system (TRS) PLoS Med. 2016;13(1):e1001946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hartung D, Zarin D, Guise J-M, McDonagh M, Paynter R, Helfand M. Reporting discrepancies between the ClinicalTrials.gov results database and peer-reviewed publications. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):477–483. doi: 10.7326/M13-0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bourgeois F, Murthy S, KD M. Outcome reporting among drug trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(3):158–166. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu X, Li Y, Yin S, Song S. Result publication of Chinese trials in World Health Organization primary registries. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prenner J, Driscoll S, Fine H, Salz D, Roth D. Publication rates of registered clinical trials in macular degeneration. Retina. 2011;31(2):401–404. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181eef2ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wildt S, Krag A, Gluud L. Characteristics of randomised trials on diseases in the digestive system registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: a retrospective analysis. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000309. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gandhi R, Jan M, Smith H, Mahomed N, Bhandari M. Comparison of published orthopaedic trauma trials following registration in Clinicaltrials.gov. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shamliyan T, Kane R. Clinical research involving children: registration, completeness, and publication. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1291–e1300. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vawdrey D, Hripcsak G. Publication bias in clinical trials of electronic health records. J Biomed Inform. 2013;46(1):139–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stockmann C, Sherwin C, Koren G, Campbell S, Constance J, Linakis M, Balch A, Varner M, Spigarelli M. Characteristics and publication patterns of obstetric studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(4):432–437. doi: 10.1002/jcph.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones C, Handler L, Crowell K, Keil L, Weaver M, Platts-Mills T. Non-publication of large randomized clinical trials: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6104. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riveros C, Dechartres A, Perrodeau E, Haneef R, Boutron I, Ravaud P. Timing and completeness of trial results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in journals. PLoS Med. 2013;10(12):e1001566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Korevaar D, Ochodo E, Bossuyt P, Hooft L. Publication and reporting of test accuracy studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. Clin Chem. 2014;60(4):651–659. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.218149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Munch T, Dufka F, Greene K, Smith S, Dworkin R, Rowbotham M. RReACT goes global: perils and pitfalls of constructing a global open-access database of registered analgesic clinical trials and trial results. PAIN®. 2014;155(7):1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khan N, Singh M, Spencer H, Torralba K. Randomized controlled trials of rheumatoid arthritis registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: what gets published and when. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66(10):2664–2674. doi: 10.1002/art.38784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Su C-X, Han M, Ren J, Li W-Y, Yue S-J, Hao Y-F, Liu J-P. Empirical evidence for outcome reporting bias in randomized clinical trials of acupuncture: comparison of registered records and subsequent publications. Trials. 2015;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-16-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hakala A, Kimmelman J, Carlisle B, Freeman G, Fergusson D. Accessibility of trial reports for drugs stalling in development: a systematic assessment of registered trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h1116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tang E, Ravaud P, Riveros C, Perrodeau E, Dechartres A. Comparison of serious adverse events posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and published in corresponding journal articles. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0430-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boccia S, Rothman K, Panic N, Flacco M, Rosso A, Pastorino R, Manzoli L, La Vecchia C, Villari P, Boffetta P. Registration practices for observational studies on clinicaltrials.gov indicated low adherence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;70:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saito H, Gill C. How frequently do the results from completed US clinical trials enter the public domain?-a statistical analysis of the Clinicaltrials.gov database. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Son C, Tavakoli S, Bartanusz V. No publication bias in industry funded clinical trials of degenerative diseases of the spine. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;25:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baudart M, Ravaud P, Baron G, Dechartres A, Haneef R, Boutron I. Public availability of results of observational studies evaluating an intervention registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0551-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chahal J, Tomescu S, Ravi B, Bach B, Ogilvie-Harris D, Mohamed N, Gandhi R. Publication of sports medicine––related randomized controlled trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):1970–1977. doi: 10.1177/0363546512448363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Manzoli L, Flacco M, D’Addario M, Capasso L, De Vito C, Marzuillo C, Villari P, Ioannidis JP. Non-publication and delayed publication of randomized trials on vaccines: survey. BMJ. 2014;348:g3058. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lebensburger J, Hilliard L, Pair L, Oster R, Howard T, Cutter G. Systematic review of interventional sickle cell trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. Clin Trials. 2015;12(6):575–583. doi: 10.1177/1740774515590811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Smith H, Bhandari M, Mahomed N, Jan M, Gandhi R. Comparison of arthroplasty trial publications after registration in ClinicalTrials.gov. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1283–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guo S-W, Evers J. Lack of transparency of clinical trials on endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1281–1290. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318291f299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsikkinis A, Cihoric N, Giannarini G, Hinz S, Briganti A, Wust P, Ost P, Ploussard G, Massard C, Surcel C. Clinical perspectives from randomized phase 3 trials on prostate cancer: an analysis of the Clinicaltrials.gov database. European Urology Focus. 2015;1(2):173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen R, Desai N, Ross J, Zhang W, Chau K, Wayda B, Murugiah K, Lu D, Mittal A, Krumholz H. Publication and reporting of clinical trial results: cross sectional analysis across academic medical centers. BMJ. 2016;352:i637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Ramsey S, Scoggins J. Commentary: practicing on the tip of an information iceberg? Evidence of underpublication of registered clinical trials in oncology. Oncologist. 2008;13(9):925–929. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hurley M, Prayle A, Smyth A. Delayed publication of clinical trials in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11(1):14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ioannidis J, Manzoli L, De Vito C, D'Addario M, Villari P. Publication delay of randomized trials on 2009 influenza A (H1N1) vaccination. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ohnmeiss D. The fate of prospective spine studies registered on www. ClinicalTrials.gov. Spine J. 2015;15(3):487–491. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gopal R, Yamashita T, Prochazka A. Research without results: inadequate public reporting of clinical trial results. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(3):486–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lampert A, Hoffmann G, Ries M. Ten years after the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ Clinical Trial Registration Initiative, one quarter of phase 3 pediatric epilepsy clinical trials still remain unpublished: a cross sectional analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0144973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gandhi G, Murad M, Fujiyoshi A, Mullan R, Flynn D, Elamin M, Swiglo B, Isley W, Guyatt G, Montori V. Patient-important outcomes in registered diabetes trials. JAMA. 2008;299(21):2543–2549. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chowers M, Gottesman B, Leibovici L, Pielmeier U, Andreassen S, Paul M. Reporting of adverse events in randomized controlled trials of highly active antiretroviral therapy: systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(2):239–250. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.You B, Gan H, Pond G, Chen EX. Consistency in the analysis and reporting of primary end points in oncology randomized controlled trials from registration to publication: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2011;30(2):210–216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reveiz L, Bonfill X, Glujovsky D, Pinzon C, Asenjo-Lobos C, Cortes M, Canon M, Bardach A, Comandé D, Cardona AF. Trial registration in Latin America and the Caribbean’s: study of randomized trials published in 2010. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(5):482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nankervis H, Baibergenova A, Williams H, Thomas K. Prospective registration and outcome-reporting bias in randomized controlled trials of eczema treatments: a systematic review. J Investig Dermatol. 2012;132(12):2727–2734. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pinto R, Elkins M, Moseley A, Sherrington C, Herbert R, Maher C, Ferreira P, Ferreira ML. Many randomized trials of physical therapy interventions are not adequately registered: a survey of 200 published trials. Phys Ther. 2012;93(3):299–309. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hannink G, Gooszen H, Rovers M. Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized clinical trials of surgical interventions. Ann Surg. 2013;257(5):818–823. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182864fa3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rosenthal R, Dwan K. Comparison of randomized controlled trial registry entries and content of reports in surgery journals. Ann Surg. 2013;257(6):1007–1015. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318283cf7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hopewell S, Collins G, Hirst A, Kirtley S, Tajar A, Gerry S, Altman D. Reporting characteristics of non-primary publications of results of randomized trials: a cross-sectional review. Trials. 2013;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Babu A, Veluswamy S, Rao P, Maiya A. Clinical trial registration in physical therapy journals: a cross-sectional study. Phys Ther. 2013;94(1):83–90. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20120531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lee S, Teoh P, Camm C, Agha R. Compliance of randomized controlled trials in trauma surgery with the CONSORT statement. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(4):562–572. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182a5399e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Li X-Q, Yang G-L, Tao K-M, Zhang H-Q, Zhou Q-H, Ling C-Q. Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials of gastroenterology and hepatology. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(12):1474–1483. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.845909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Norris S, Holmer H, Fu R, Ogden L, Viswanathan M, Abou‐Setta A. Clinical trial registries are of minimal use for identifying selective outcome and analysis reporting. Res Synthesis Methods. 2014;5(3):273–284. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hardt J, Metzendorf M-I, Meerpohl J. Surgical trials and trial registers: a cross-sectional study of randomized controlled trials published in journals requiring trial registration in the author instructions. Trials. 2013;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Anand V, Scales D, Parshuram C, Kavanagh B. Registration and design alterations of clinical trials in critical care: a cross-sectional observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(5):700–722. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mann E, Nguyen N, Fleischer S, Meyer G. Compliance with trial registration in five core journals of clinical geriatrics: a survey of original publications on randomised controlled trials from 2008 to 2012. Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):872–876. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Walker K, Stevenson G, Thornton J. Discrepancies between registration and publication of randomised controlled trials: an observational study. JRSM Open. 2014;5(5):2042533313517688. doi: 10.1177/2042533313517688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dekkers O, Cevallos M, Bührer J, Poncet A, Rau S, Perneger T, Egger M. Comparison of noninferiority margins reported in protocols and publications showed incomplete and inconsistent reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(5):510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Østervig R, Sonne A, Rasmussen L. Registration of randomized clinical trials––a challenge. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015;59(8):986–989. doi: 10.1111/aas.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.De Oliveira JG, Jung M, McCarthy R. Discrepancies between randomized controlled trial registry entries and content of corresponding manuscripts reported in anesthesiology journals. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(4):1030–1033. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dal-Ré R, Ross J, Marušić A. Compliance with prospective trial registration guidance remained low in high-impact journals and has implications for primary end point reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Reveiz L, Cortés-Jofré M, Lobos C, Nicita G, Ciapponi A, Garcìa-Dieguez M, Tellez D, Delgado M, Solà I, Ospina E. Influence of trial registration on reporting quality of randomized trials: study from highest ranked journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1216–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rongen J, Hannink G. Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials of orthopaedic surgical interventions. J Bone Joint Surg. 2016;98(5):403–409. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vera-Badillo F, Shapiro R, Ocana A, Amir E, Tannock I. Bias in reporting of end points of efficacy and toxicity in randomized, clinical trials for women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(5):1238–1244. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.McGee R, Su M, Kelly P, Higgins G, Craig J, Webster A. Trial registration and declaration of registration by authors of randomized controlled trials. Transplantation. 2011;92(10):1094–1100. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318232baf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Huić M, Marušić M, Marušić A. Completeness and changes in registered data and reporting bias of randomized controlled trials in ICMJE journals after trial registration policy. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Korevaar D, Bossuyt P, Hooft L. Infrequent and incomplete registration of test accuracy studies: analysis of recent study reports. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e004596. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jones C, Platts-Mills T. Quality of registration for clinical trials published in emergency medicine journals. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(4):458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Smaïl-Faugeron V, Fron-Chabouis H, Durieux P. Clinical trial registration in oral health journals. J Dent Res. 2015;94(3 suppl):8S–13S. doi: 10.1177/0022034514552492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Riehm K, Azar M, Thombs B. Transparency of outcome reporting and trial registration of randomized controlled trials in top psychosomatic and behavioral health journals: a 5-year follow-up. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials