Abstract

Alcohol use disorders are a costly public health dilemma. Complicating this issue is the general lack of basic research assessing sex differences in many aspects of alcohol seeking and taking behaviors. The current experiments sought to decrease this gap in our understanding of sex differences in alcohol use disorders by assessing both male and female Long-Evans rats in parallel on alcohol self-administration, relapse-like behavior following abstinence and extinction, and motivation to respond for the standard alcohol solution and a quinine-adulterated alcohol solution. Here, we show that while males tend to have greater alcohol-reinforced responses throughout self-administration training, females show similar or greater alcohol intake (g/kg). Additionally, when tested for reinstatement of alcohol seeking and self-administration, following abstinence or extinction, males consistently showed greater reinstatement responding than females, which may be related to their training history. However, when assessed using the progressive ratio, there were no sex differences in motivation to respond for alcohol. Further, the consistent patterns of responding across months of self-administration training in both males and females, lend support for the feasibility of conducting these studies in male and female rats in parallel without concerns about daily variability. Our data also suggest that males and females should not be pooled as differences in alcohol lever responses and differences in reinstatement, as observed in the current experiments, could affect the overall outcome and possibly confound data interpretation. These studies demonstrate the importance of assessing males and females in parallel and advance the body of preclinical research on sex differences in alcohol self-administration and relapse.

Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) constitute one of the greatest public health risks worldwide. Recent reports from the World Health Organization (WHO 2014) show that men consume more alcohol than women, although this gap is closing (Dawson et al. 2015; Keyes et al. 2008; Keyes et al. 2011). Moreover, differences between male and female drinking patterns have been decreasing (Keyes et al. 2010). Men also show a higher lifetime prevalence of AUDs (Grant et al. 2015). Interestingly, while women tend to start drinking at a later age, there is evidence that they accelerate to dependence faster than males in what has been termed “telescoping” (Diehl et al. 2007; Ehlers et al. 2010; Erol and Karpyak 2015; Mann et al. 2005; Randall et al. 1999; Schuckit et al. 1995; Schuckit et al. 1998), but see (Keyes et al. 2010; Sharrett-Field et al. 2013). Furthermore, men and women do not differ in length of abstinence prior to resuming drinking (Foster et al. 2000; Greenfield et al. 2000) and show similar response to acamprosate and naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence (Baros et al. 2008; Greenfield et al. 2010; Mason and Lehert 2012).

Considering these sex differences observed in clinical populations, strikingly few preclinical animal studies of alcohol use have directly compared males and females (Becker et al. 2011; Becker and Koob 2016; Beery and Zucker 2011; Guizzetti et al. 2016; Priddy et al. 2017). This has traditionally been related to concerns about variability related to hormones and estrous cycle in females. However, meta-analysis of studies in rats has demonstrated that females are no more variable than males on a variety of behavioral tasks (Becker et al. 2016). In the available preclinical research using rats, studies assessing sex differences in alcohol consumption using a two-bottle choice paradigm have shown that female rats of several strains consume more alcohol and are less sensitive to changes in alcohol concentration as compared to males (Lancaster and Spiegel 1992; Li and Lumeng 1984; Meliska et al. 1995). The literature on operant alcohol self-administration has mixed findings showing either no difference between males and females (Moore and Lynch 2015; Priddy et al. 2017) or females responding and consuming more than males (Bertholomey et al. 2016; Priddy et al. 2017), which appears to be strain-dependent. Preclinical studies of sex differences in relapse-like behaviors related to alcohol are also limited. One study shows that after repeated periods of forced abstinence, female rats show an enhanced alcohol deprivation effect relative to males (Garcia-Burgos et al. 2010). This effect has also been observed in rats bred to display a depressive-like phenotype (Vengeliene et al. 2005). Another study showed that adult female rats, but not males, exhibited greater cue-induced and yohimbine-induced alcohol seeking following chronic corticosterone exposure in adolescence (Bertholomey et al. 2016).

As a majority of the self-administration studies in our lab and others involve long-term self-administration (>5 months), the current studies sought to examine sex differences in the acquisition and maintenance of long-term operant alcohol self-administration in Long Evans rats. In addition, sex differences in reinstatement of alcohol self-administration following both a abstinence period and following explicit extinction training was examined. Lastly, sex differences in motivation to respond for alcohol using a progressive ratio operant schedule and quinine adulteration to devalue the alcohol was examined. Based on the existing operant self-administration literature, we hypothesized greater alcohol self-administration, enhanced reinstatement of alcohol seeking, and less sensitivity to quinine adulteration in female than male rats.

Materials and Methods

Animals

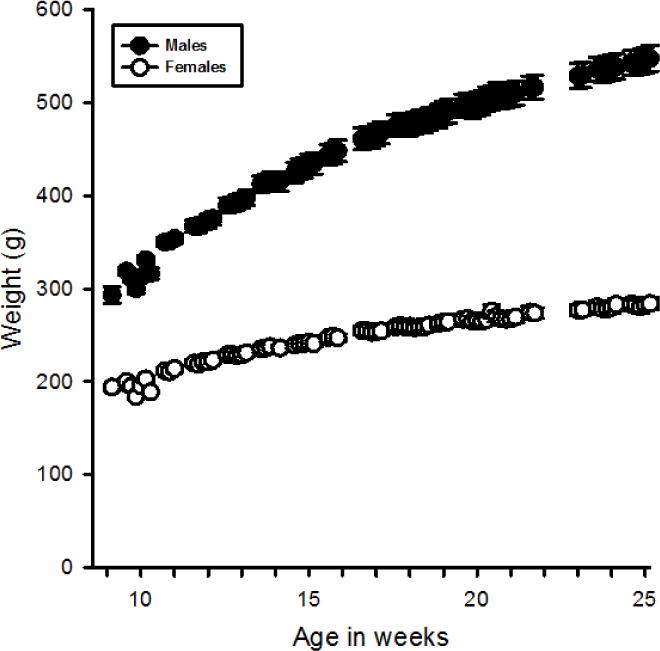

24 adult Long-Evans rats (12 female/12 male) were housed in same-sex pairs in ventilated cages with access to food and water ad libitum in the home cage. Animals were 7 weeks upon arrival to the colony and 9 weeks upon the start of training. The animals were weighed regularly across the duration of the experiment (Figure 2). The colony room was maintained on a 12 hour light/dark schedule (lights on at 07:00) with all experiments being conducted during the light portion of the schedule. Animals were under continuous care and monitoring by veterinary staff from the Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine (DLAM) at UNC-Chapel Hill. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and institutional guidelines. All protocols were approved by the UNC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). UNC-Chapel Hill is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

Figure 2.

Mean(+SEM) weight (grams) for males and females over the course of the study. Males weighed significantly more than females throughout all experiments.

Apparatus

Self-administration chambers (Med Associates Inc, St. Albans, VT, USA) were individually located within sound attenuating chambers with an exhaust fan to circulate air and mask outside sounds. Chambers were fitted with a retractable lever on the opposite walls (left and right) of the chamber. There was a cue light above each lever and liquid receptacles in the center panels adjacent both levers. Responses on the left (i.e. active) lever resulted in cue light illumination, stimulus tone and delivery of 0.1 ml of solution across 1.66 sec via a syringe pump into the left receptacle once the response requirement was met. Responses on the right (inactive) lever had no programmed consequence. The chambers also had infrared photobeams which divided the floor into four zones to record locomotor activity throughout each session.

Alcohol self-administration training

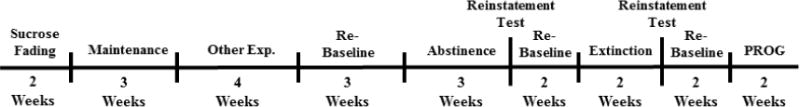

An experimental timeline has been included (Figure 1) to show the progression of the experiments. Self-administration sessions (30 min) took place 5 days per week (M-F) with the active lever on a fixed ratio 2 (FR2) schedule of reinforcement such that every second response resulted in delivery of alcohol. A sucrose fading procedure was used in which alcohol was gradually added to the 10% (w/v) sucrose solution. The exact order of exposure was as follows: 2% (v/v) alcohol/10% (w/v) sucrose (2A/10S), 5A/10S, 10A/10S, 10A/5S, 15A/5S, 15A/2S, 15A, 15A/2S. Following sucrose fading, sweetened alcohol (15A/2S) was the reinforcer for the remainder of the study.

Figure 1.

Timeline of experiments

Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC)

To examine sex differences in blood alcohol concentration, on a non-training day after rats had acquired stable self-administration, all rats received 1 g/kg alcohol via intragastric gavage (IG) and tail blood was collected 10, 30, 60, 120 and 240 min post-injection. This dose was selected based on previous studies from our lab. The route of administration was selected to allow for control of dose (as opposed to following a self-administration session). Samples were analyzed using an Analox analyzer (Analox Instruments LTD., London, UK).

Acquisition and maintenance of alcohol self-administration

Male and female rats were trained in parallel and self-administration performance was compared for sucrose fading (acquisition) and three weeks of maintenance (15A/2S). For 4 intervening weeks, self-administration continued but the rats were used for a separate unrelated assessment that is not included in this paper. At the conclusion of that experiment, all rats underwent an additional 15 days of self-administration to ensure stable baseline responding prior to starting the next phase of the experiment.

Relapse-like behavior following abstinence

To examine the effects of self-administration following an abstinence period, rats remained in the home cage without access to alcohol for a period of 3 weeks. Following this period, rats underwent a seeking/reinstatement test session. This 30 minute test session was divided into two phases. The first 10 min was under extinction conditions in which lever responses resulted in cue presentation but no alcohol delivery (seeking phase). At the 10 minute mark, a non-contingent presentation of the cues with a single alcohol delivery (0.1 ml) occurred. For the remaining 20 min of the session, alcohol was available and the session was identical to a standard self-administration session (reinstatement of self-administration phase). The goal of this test was to assess both the relative levels of alcohol-seeking between males and females and the potential differential effects of self-administration following the seeking period.

Relapse-like behavior following extinction

Following abstinence and reinstatement, rats underwent an additional 2 weeks of self-administration training. To examine the effects of extinction on reinstatement of self-administration, rats underwent extinction sessions in which responding on either lever had no programmed consequence (i.e., no cues were presented). After 13 extinction sessions (at which point responding was 15% of baseline responding and stable), rats were tested using the same seeking/reinstatement test procedure, with the exception that the cues were not activated during the seeking phase (i.e., same as extinction training). Similar to the first test, there was a single non-contingent presentation of the cues and alcohol at the ten minute mark, and from this point forward, the session was identical to a standard self-administration session.

Motivational challenge to respond for alcohol

Following extinction and reinstatement, rats underwent an additional 2 weeks of self-administration training. Next, to examine motivation to respond for alcohol, rats were tested on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. On these sessions, the fixed ratio requirement increased by one additional response for each reinforcement earned (i.e., FR1, 2, 3, 4.. .etc). In addition, the bitter tastant quinine hydrochloride dihydrate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the 2S/15A solution (0, 0.1, 0.3, 0.9 g/L) in order to determine motivation to respond for alcohol under taste adulteration. Quinine concentration was randomized until all rats received all concentrations. Breakpoint was defined as the highest ratio completed. All rats were given at least two baseline self-administration sessions between each progressive ratio test session to ensure stable self-administration (2 baseline sessions prior to a given progressive ratio test did not differ).

Statistical Analysis

For acquisition of self-administration, alcohol lever responses, estimated alcohol intake (g/kg; calculated based on rat body weight and number of reinforcers delivered) and locomotor rate were analyzed using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) with sex as the between groups factor. Post-hoc analysis (Tukey) was used to determine differences between specific days of training. Alcohol lever responses for the intervening maintenance blocks was analyzed using two-way RM-ANOVA with sex as the between subjects factor and post hoc analysis (Tukey) to determine differences in specific days. Alcohol intake (g/kg) and locomotor rate for these maintenance blocks were averaged by week (M-F) and compared with paired-wise comparisons (t-test). For extinction sessions, alcohol responses and locomotor rate were analyzed using two-way RM-ANOVA with sex as the between subjects factor and post-hoc analysis (Tukey) to determine differences on specific extinction sessions. For extinction-reinstatement tests, the sessions was divided into ten minute segments and analyzed using two-way RM ANOVA with sex as the between subjects factor. Post-hoc analysis was used to determine differences between specific session segments and between sexes. To determine differences in BAC, two-way RM ANOVA with sex as the between subjects factor was used. Post-hoc analysis was used to determine differences between specific time points and between sexes.

Results

Acquisition and maintenance of alcohol self-administration

Acquisition

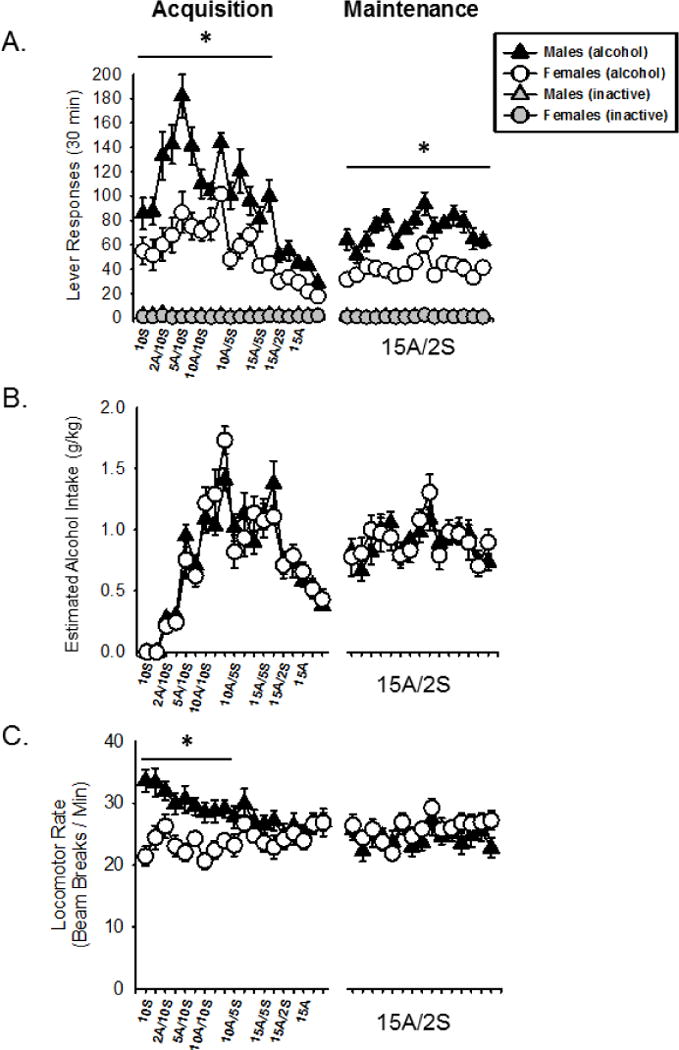

Alcohol lever responses across sucrose fading are shown in Figure 3A (left of axis break). Two-way ANOVA showed a main effect of session (F[18,396] = 22.823, p < 0.01), a main effect of sex (F[1,22] = 27.460, p < 0.01) and a sex by session interaction (F[18,396] = 3.118, p < 0.01). Post hoc analysis showed that males responded significantly more than females on all alcohol/sucrose concentrations through 15A/5S (Figure 3A; no difference in inactive lever responses we observed). However, there was no difference in alcohol intake (g/kg) between males and females during acquisition (Figure 3B), which is related to the lower body weight of the females (Fig 2). As such, females required significantly less volume (i.e., reinforcements) to achieve the same level of alcohol intake. As shown in Figure 3C, two-way ANOVA found a significant main effect of session (F[18,396] = 3.325, p < 0.01), sex (F[1,22] = 6.142, p < 0.05) and a sex by session interaction (F[18,396] =4.520, p < 0.01) on locomotor rate during acquisition. Post hoc analysis showed that males were more active (i.e., higher locomotor rates) at all concentrations up to 10A/5S.

Figure 3.

Acquisition and maintenance of alcohol self-administration. Mean(+SEM) lever responses (A), estimated alcohol intake (g/kg, B) and locomotor rate (C) for sucrose fading (acquisition) and 15 days of maintenance following acquisition. Males lever pressed significantly more than females at all fading concentrations through 15A/5S and on all maintenance sessions. Alcohol intake (g/kg) did not differ at any point in acquisition or maintenance. Males had greater locomotor rate at fading concentrations through 10A/10S. * - p < 0.05, significant sex difference.

Maintenance

Alcohol lever responses across the first 15 days of maintenance of self-administration (15A/2S) are also illustrated in Figure 3A (right of axis break). A two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of sex (F[1,308] = 26.299, p < 0.01), a significant main effect of session (F[14,308] = 4.447, p < 0.05), and a sex by session interaction (F[14,308] = 4.541, p < 0.01), with males showing greater responding on the alcohol lever than females on every session (no differences in inactive lever responses). However, alcohol intake (g/kg; Figure 3B) did not significantly differ between males and females, similar to the pattern observed during acquisition. Additionally, no sex differences in locomotor rate were observed (Figure 3C).

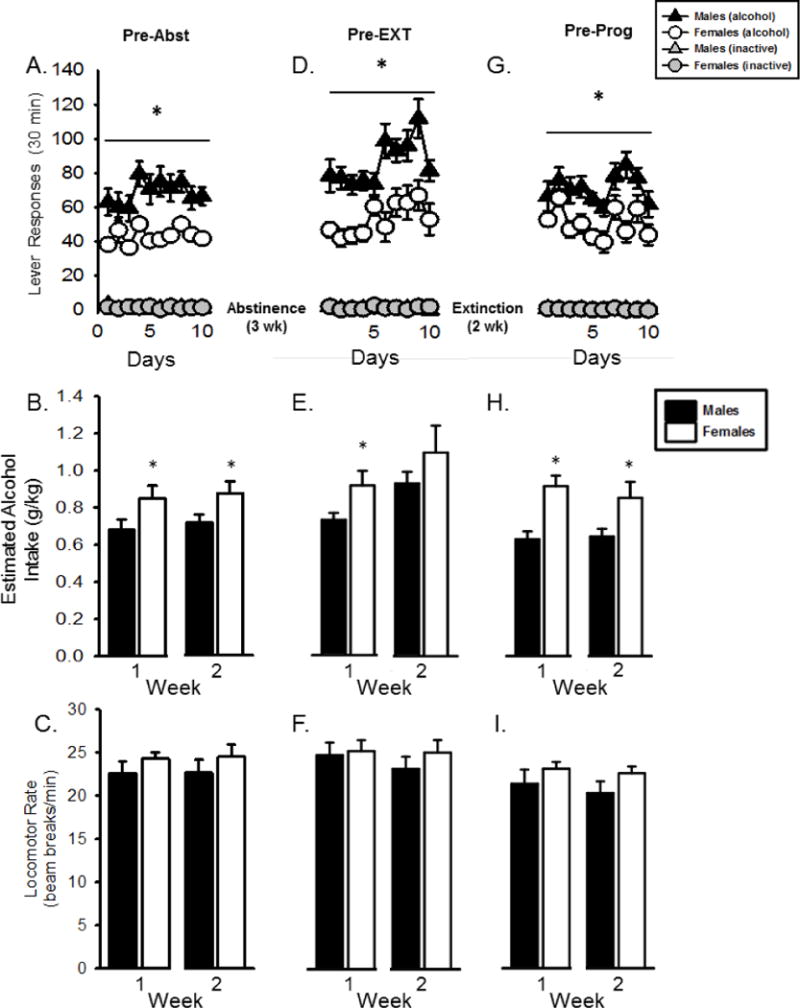

Reinstatement following abstinence

Self-administration for the last ten sessions of the maintenance period prior to the 3 week abstinence period is shown in Figure 4A. Alcohol lever responses were higher in the males relative to the females (F[1,22] = 21.761, p < 0.01) and average alcohol intake (g/kg) was significantly higher in the females for both weeks (p < 0.05, Fig 4B). There were no differences between males and females in average locomotor rate (Fig 4C).

Figure 4.

Maintenance of alcohol self-administration prior to each experiment. Mean(+SEM) lever responses for the ten sessions prior to abstinence (A), extinction (D) and progressive ratio testing (G). 5 day means (+SEM) for estimated alcohol intake (g/kg) and locomotor rate prior to abstinence (B/C), extinction (E/F) and progressive ratio testing (H/I). Males responded significantly more than females on all maintenance sessions. Females showed significantly higher alcohol intake (g/kg) with the exception of week 2 prior to extinction. Locomotor rate did not differ between males and females for maintenance sessions. * - p < 0.05, significant sex difference.

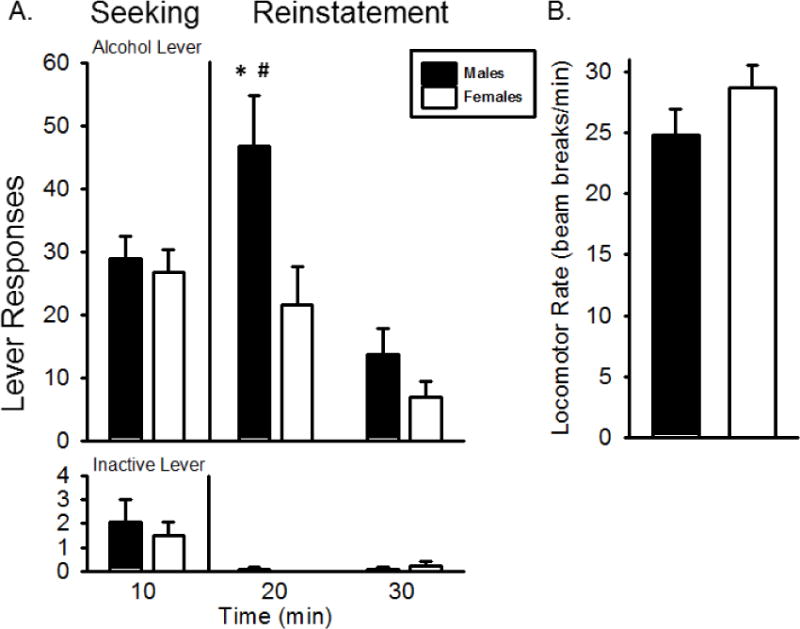

Following the 3 week abstinence period, rats were tested on a seeking/reinstatement session. As shown in Figure 5, there was a significant main effect of test phase (F[2,22] = 12.057, p < 0.01) and a sex by test phase interaction (F[2,22] = 3.90, p < 0.05) on alcohol lever responses. Males and females did not differ in alcohol lever responses during the seeking phase of the test; however, males responded significantly more during the 2nd 10 minutes as compared to females (p<0.05). However, alcohol intake (g/kg) during the SA phase of the session did not significantly differ between males and females (0.60+0.08 and 0.55+0.13, respectively). There was no significant difference in inactive lever responses or locomotor rate between females and males (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Reinstatement following abstinence. Mean(+SEM) lever responses (A) and locomotor rate (B) for the reinstatement test session following 3 weeks of abstinence. Male rats had significantly more responses in the first 10 minutes of reinstatement (minutes 10–20) than during the seeking phase (minutes 0–10). In addition, males had significantly more responses during this phase than females. There were no significant differences in locomotor rate. * - p < 0.05, significantly different from seeking phase. # - p < 0.05, males significantly higher than females.

Explicit Extinction and Reinstatement

Following abstinence and reinstatement, rats underwent 10 baseline self-administration sessions prior to beginning extinction sessions (Figure 4D). One female was lost due to illness during extinction, and therefore n=11 for the female group from this point forward. Males had greater alcohol lever responses than females (F[1,20] = 20.283, p < 0.01) however, average alcohol intake (g/kg) in the first week was significantly higher in females (p < 0.05, Fig 4E). There were no differences in average locomotor rate for the two weeks (Fig 4F).

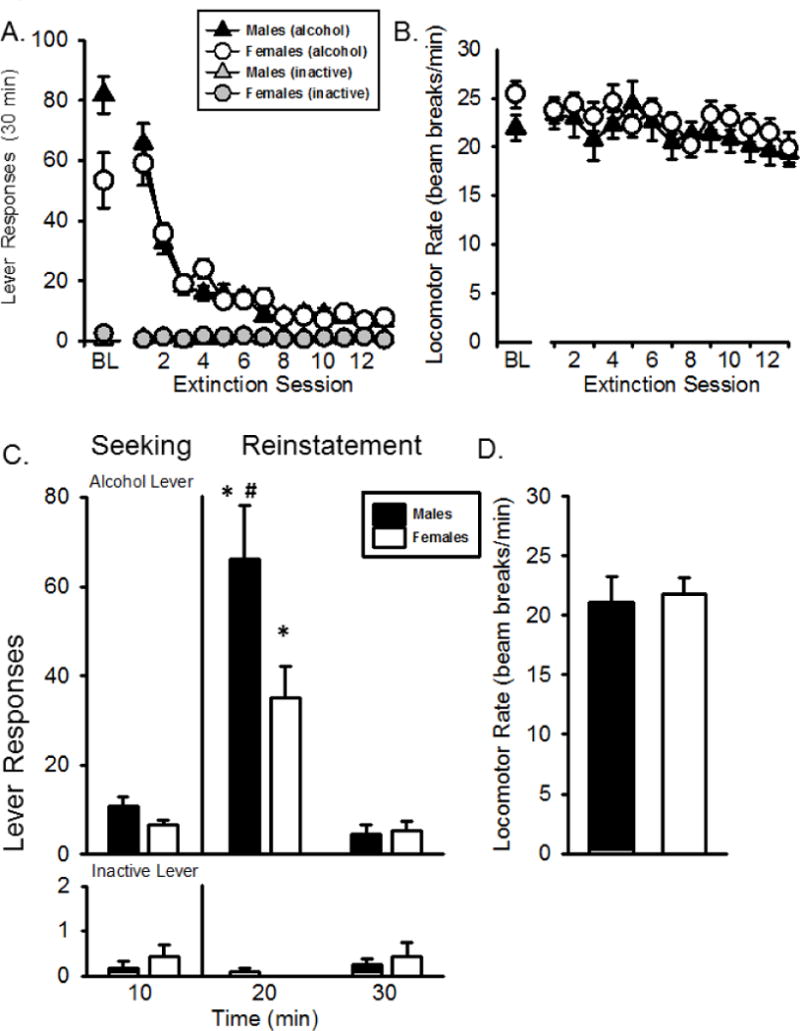

Lever responding during extinction is shown in Figure 6A. Baseline responding (i.e., last day prior to extinction) is illustrated to the left of the axis break and was not included in the overall analysis. There was a significant main effect of extinction day (F[13,273] = 67.992, p < 0.01), indicating that responding on the alcohol lever significantly decreased across extinction session (Fig 6A). There was no effect of sex or sex by day interaction indicating no sex differences in the rate of extinction, which is interesting given the differences in baseline self-administration. Locomotor rate significantly decreased across extinction day (F[13,273] = 4.293, p < 0.01; Fig 6B), with no effect of sex or sex by extinction session interaction. Furthermore, no differences in inactive lever responses were observed.

Figure 6.

Extinction and Reinstatement testing. Mean(+SEM) lever responses (A) and locomotor rate (B) during extinction sessions. There was no significant difference between males and females during extinction. * - p < 0.05, significantly different from seeking phase. # - p < 0.05, males significantly higher than females.

When tested for reinstatement following extinction, there was a significant effect of sex (F[1,20] = 5.507, p < 0.05), phase (F[2,20] = 74.516, p < 0.01) and a sex by phase interaction (F[2,20] = 5.960, p < 0.01) on alcohol lever responses (Figure 6C). There were no sex differences during the seeking phase, but post hoc analysis showed that males responded more than females during the first phase of reinstatement (minutes 10–20; p<0.05). However, similar to the first reinstatement test, alcohol intake (g/kg) did not differ between males and females for the SA phase (0.92+0.16 and 0.57+0.13, respectively). Both females and males responded more during the first phase of reinstatement than either the seeking phase (minutes 0–10) or the second phase of reinstatement (minutes 20–30), again demonstrating reinstatement of alcohol self-administration following the non-contingent presentation of the cues and alcohol reinforcer. There were no significant differences in inactive lever responses or locomotor rates across the session or between females and males.

Progressive Ratio + Quinine

Baseline alcohol responses, average alcohol intake (g/kg) and average locomotor rate prior to progressive ratio testing are shown in Figure 4 (panels G, H, I). Alcohol lever responses were greater in the males than the females on the ten days prior to progressive ratio testing (F[1,21] = 11.749, p < 0.01, Fig 4G). Alcohol intake in females was significantly higher than males on both weeks (p < 0.05, Fig 4H) and locomotor rate did not differ between males and females (Fig. 4I)

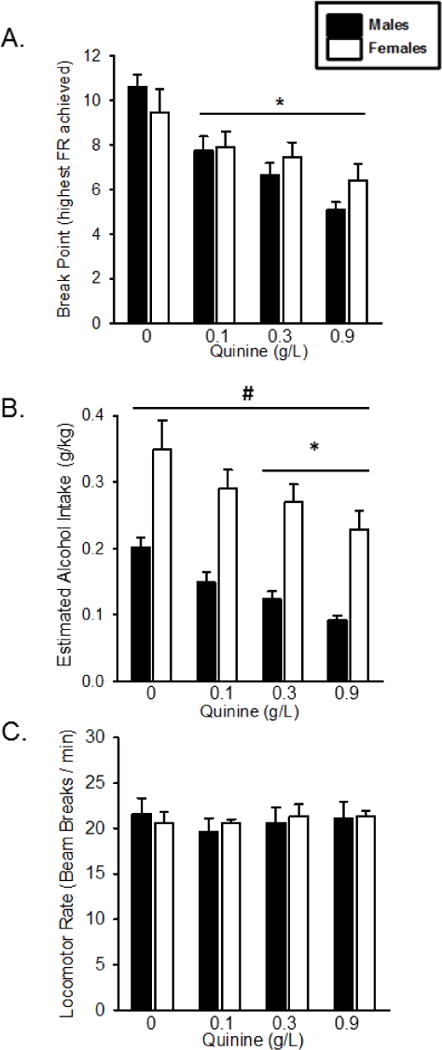

As shown in Figure 7A, there was a significant effect of quinine concentration on progressive ratio break point (F[3,27] = 19.738, p < 0.01), with decreased breakpoint at all quinine concentrations compared to alcohol alone, indicating that both males and females were affected by taste adulteration. There was no significant effect of sex or a sex by quinine interaction on break point. In contrast, as shown in Figure 7B, there was a significant effect of sex (F[1,27] = 25.671, p < 0.01), with females having higher alcohol intake levels. There was also a main effect of quinine concentration (F[3,27] = 12.222, p < 0.01) with reduced alcohol intake following both 0.3 and 0.9 g/L concentrations of quinine relative to alcohol alone. This shows that quinine reduced responding for alcohol at the same doses in both males and females. There were no significant effects on inactive lever responses or locomotor rate (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Motivation to respond for alcohol as measured by a progressive ratio. Mean(+SEM) break point (highest ratio achieved, A), estimated alcohol intake (g/kg, B) and locomotor rate (C). As quinine concentration increased, breakpoint decreased, however there was no difference between males and females. Alcohol intake was decreased at 0.3 and 0.9 g/L quinine. Alcohol intake in females was significantly higher than males at all concentrations of quinine. Locomotor rate did not differ between males and females and was not affected by quinine. * - p < 0.05, quinine concentration significantly different from 15A/2S alone. # - p < 0.05, females significantly higher than males.

Blood Alcohol Concentration Analysis

As shown in Table 1, there was a significant effect of time point on BAC (F[4,20] = 15.492, p < 0.01). Post hoc analysis showed that BAC reached a stable peak from 30 to 60 minutes post-injection (significantly higher than all other time points) before decreasing. BAC did not differ between females and males. Analysis of area under the curve showed no significant difference between males and females.

Table 1.

Mean (+S.E.M.) mg/dl blood alcohol concentration (BAC) and area under the curve (AUC) following alcohol (1 g/kg), IG.

| BAC (mg/dl) | 10 min | 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | 240 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Females | 19.29+3.96 | 44.50+10.72 | 43.11+9.52 | 16.52+5.69 | 5.49+2.11 | |

| Males | 18.22+3.95 | 48.74+6.98 | 52.13+7.18 | 31.00+10.21 | 5.10+1.81 | |

|

| ||||||

| AUC | ||||||

| Females | 5062.50+1023.49 | |||||

| Males | 6843.66+1232.04 | |||||

Discussion

The current experiments assessed whether there were sex differences in alcohol self-administration related behaviors in Long-Evans rats. One of the consistent findings throughout these experiments was that while males showed greater alcohol-reinforced responding than females during self-administration sessions, females showed similar or greater alcohol intake (g/kg) than males. This finding is supported by several studies of alcohol consumption in outbred rat strains (Long-Evans, Wistar, Wistar Kyoto, Sprague-Dawley) in which males and females have been shown to consume similar amounts of alcohol (Schramm-Sapyta et al. 2014; van Haaren and Anderson 1994; Varlinskaya and Spear 2015) or females consume more alcohol than males (Almeida et al. 1998; Cailhol and Mormede 2001; Juarez and Barrios de Tomasi 1999; Lancaster and Spiegel 1992; Vetter-O’Hagen et al. 2009). Moreover, similar levels of alcohol intake between males and females have been observed previously in P-rats and Long-Evans (Moore and Lynch 2015; Priddy et al. 2017). Additionally, as shown in Figures 3 and 4, daily alcohol self-administration was highly consistent across the duration of the study in both males and females. This is important to inform future studies as stable self-administration patterns are important for repeated drug testing or other manipulations. Further, the consistent daily self-administration patterns in the females suggest that under these self-administration conditions, estrous phase likely did not dramatically impact behavior. This finding is further supported by Priddy et al. (2017) which showed that alcohol preference and intake were not significantly different across estrous phase in female Long-Evans rats. However, it will be important for future work to examine this directly by confirming phase of estrous throughout the study.

In addition to assessing the maintenance of alcohol self-administration patterns across time between males and females, the current experiments also sought to examine whether there were sex differences in reinstatement of alcohol self-administration after abstinence or extinction. Following three weeks of abstinence, there were no sex differences in alcohol seeking (i.e., first ten minutes of the reinstatement test session), which is interesting given that males tended to have higher alcohol-reinforced responses than females during alcohol self-administration sessions. Once the alcohol-paired cues were presented and 0.1 ml of alcohol was delivered, males, but not females, showed a significant increase in alcohol lever responding compared to the seeking phase. However, alcohol intake during this period did not differ, suggesting that males and females showed similar motivation for alcohol when it became available.

In the second assessment of relapse-like behavior, rats underwent explicit extinction training prior to the reinstatement test. There were no sex differences in alcohol lever responding throughout extinction training, which is surprising given the consistently higher alcohol lever responding in the males throughout daily self-administration training. During the reinstatement test, there were no sex differences during the seeking phase of the reinstatement test, consistent with the findings of the prior reinstatement test (following abstinence). Importantly, this work presents 3 instances in which there were no sex differences under non-reinforced conditions, suggesting that males and females are equally sensitive to the removal of the reinforcer. When the cues were activated, both males and females showed an increase in alcohol-reinforced responding relative to the seeking phase. Again, males responded significantly more than females (Fig 6). This is in contrast to the initial reinstatement test following the abstinence period and suggests that presentation of the alcohol and alcohol-related cues following explicit extinction training may create a more salient contrast than home cage abstinence. It is also worth considering that this was the second reinstatement test, thus this outcome may be explained by experience. That is, the females may have required more experience with the testing procedure than males. Moreover, similar to the first reinstatement session, alcohol intake (g/kg) did not differ between males and females, again suggesting that motivation for alcohol did not differ between males and females. Furthermore, this finding is supported by a previous study assessing the enhancement of alcohol intake following a deprivation period (alcohol deprivation effect) showing no difference between males and females (P-rats, (McKinzie et al. 1998).

The final set of experiments sought to assess whether there was a sex difference in motivation to respond for alcohol. One of the most striking findings from this assessment was that under progressive ratio conditions, there was no sex difference in break point. That is, males and females showed equal motivation to respond for alcohol. This is important given that males had consistently responded at higher levels during self-administration training. Similar findings have been observed in P-rats in which male and female rats show similar break points when trained on a progressive ratio schedule (Moore and Lynch 2015). The current progressive ratio findings, considered in the context of the maintenance of self-administration, suggest that under a fixed ratio requirement, responding is driven by achieving a specific alcohol intake (g/kg) as consistent daily responding is observed throughout training. In contrast, under progressive ratio conditions, an increasing amount of effort is required with each reinforcement, and as such, responding is driven by how motivated each rat is to respond for alcohol. It is important to note however, that in the current experiments, break points and resulting alcohol intake was considerably lower in both males and females than during maintenance, even in the absence of quinine. This would suggest that overall; Long-Evans rats are not highly motivated toward consuming alcohol under the current conditions. These findings are similar to those observed in other studies utilizing a progressive ratio for alcohol self-administration in which reinforcements earned or resulting intake (g/kg) are similar to the current findings (Besheer et al. 2008; Moore and Lynch 2015; Spoelder et al. 2015).

In addition to assessing motivation to respond for alcohol using the progressive ratio schedule, the bitter tastant quinine was also added in increasing concentrations to the alcohol solution to determine whether there was a sex differences in the effects of reinforcer devaluation. Alcohol responding decreased as quinine concentration increased in both males and females, indicating that both sexes were equally sensitive to reinforcer devaluation . The literature on sex differences in response to quinine in rats is mixed with some finding a stronger aversion in males (Nance 1976), females (Clarke and Ossenkopp 1998), or no difference (Wade and Zucker 1970). Furthermore, (Wade and Zucker 1969) and Clarke and Ossenkopp (1998) have shown that levels of estradiol and specific phase of estrous plays a role in sensitivity to quinine in female rats. It will be interesting for future work to systematically evaluate phase of estrous and quinine concentration in parallel to determine whether there are differential effects between males and females that are dependent on phase of estrous.

The current series of experiments demonstrate that while male and female Long-Evans rats show similar alcohol intake during ongoing self-administration, they show differences related to aspects of relapse-like behavior. Further, the consistent patterns of responding across months of self-administration training in both males and females, lend support for the feasibility of conducting these types of self-administration studies in male and female rats in parallel without concerns about daily variability. However, our data suggest that males and females should not be pooled as differences in alcohol lever responses and differences in reinstatement, as observed in the current experiments, could affect the overall outcome and possibly confound data interpretation. Furthermore, sex differences may emerge in response to behavioral (as demonstrated in this work) or pharmacological challenges, which will lead to a better understanding sex differences in a variety of models of drug abuse and treatment. In general, these findings are encouraging for the prospect of gaining a greater representation of female subjects in preclinical studies of alcohol use and increasing our understanding of sex-related factors influencing alcohol intake, alcohol seeking, reinstatement of alcohol self-administration and motivation to respond for alcohol.

Highlights.

Examining sex differences in alcohol self-administration has been understudied.

Estimated alcohol intake (g/kg) in females was the same or greater than males.

There was no sex difference in estimated alcohol intake during reinstatement.

Males and females showed similar progressive ratio break points.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by funds from the National Institutes of Health AA019682, Office of the Director, NIH (JB), AA07573, and by the Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almeida OF, Shoaib M, Deicke J, Fischer D, Darwish MH, Patchev VK. Gender differences in ethanol preference and ingestion in rats. The role of the gonadal steroid environment. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2677–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baros AM, Latham PK, Anton RF. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of alcohol dependence: do sex differences exist? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:771–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF, Doremus-Fitzwater TL. Effects of stress on alcohol drinking: a review of animal studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:131–56. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, Koob GF. Sex Differences in Animal Models: Focus on Addiction. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:242–63. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, Prendergast BJ, Liang JW. Female rats are not more variable than male rats: a meta-analysis of neuroscience studies. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7:34. doi: 10.1186/s13293-016-0087-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Zucker I. Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholomey ML, Nagarajan V, Torregrossa MM. Sex differences in reinstatement of alcohol seeking in response to cues and yohimbine in rats with and without a history of adolescent corticosterone exposure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233:2277–87. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4278-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besheer J, Faccidomo S, Grondin JJ, Hodge CW. Regulation of motivation to self-administer ethanol by mGluR5 in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:209–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cailhol S, Mormede P. Sex and strain differences in ethanol drinking: effects of gonadectomy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:594–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SN, Ossenkopp KP. Taste reactivity responses in rats: influence of sex and the estrous cycle. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R718–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.3.R718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Grant BF. Changes in alcohol consumption: United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl A, Croissant B, Batra A, Mundle G, Nakovics H, Mann K. Alcoholism in women: is it different in onset and outcome compared to men? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257:344–51. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0737-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Vieten C, Gilder A, Gilder DA, Stouffer GM, Lau P, Wilhelmsen KC. Age at regular drinking, clinical course, and heritability of alcohol dependence in the San Francisco family study: a gender analysis. Am J Addict. 2010;19:101–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol A, Karpyak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JH, Marshall EJ, Peters TJ. Application of a quality of life measure, the life situation survey (LSS), to alcohol-dependent subjects in relapse and remission. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1687–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Burgos D, Manrique Zuluaga T, Gallo Torre M, Gonzalez Reyes F. Sex differences in the alcohol deprivation effect in rats. Psicothema. 2010;22:887–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–66. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Hufford MR, Vagge LM, Muenz LR, Costello ME, Weiss RD. The relationship of self-efficacy expectancies to relapse among alcohol dependent men and women: a prospective study. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:345–51. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Pettinati HM, O’Malley S, Randall PK, Randall CL. Gender differences in alcohol treatment: an analysis of outcome from the COMBINE study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1803–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizzetti M, Davies DL, Egli M, Finn DA, Molina P, Regunathan S, Robinson DL, Sohrabji F. Sex and the Lab: An Alcohol-Focused Commentary on the NIH Initiative to Balance Sex in Cell and Animal Studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:1182–91. doi: 10.1111/acer.13072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez J, Barrios de Tomasi E. Sex differences in alcohol drinking patterns during forced and voluntary consumption in rats. Alcohol. 1999;19:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and the dimensionality of alcohol disorders. Psychol Med. 2011;41:629–40. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Martins SS, Blanco C, Hasin DS. Telescoping and gender differences in alcohol dependence: new evidence from two national surveys. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:969–76. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster FE, Spiegel KS. Alcoholic and nonalcoholic beer drinking during gestation: offspring growth and glucose metabolism. Alcohol. 1992;9:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(92)90003-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Lumeng L. Alcohol preference and voluntary alcohol intakes of inbred rat strains and the National Institutes of Health heterogeneous stock of rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1984;8:485–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K, Ackermann K, Croissant B, Mundle G, Nakovics H, Diehl A. Neuroimaging of gender differences in alcohol dependence: are women more vulnerable? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:896–901. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164376.69978.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason BJ, Lehert P. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence: a sex-specific meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:497–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinzie DL, Nowak KL, Murphy JM, Li TK, Lumeng L, McBride WJ. Development of alcohol drinking behavior in rat lines selectively bred for divergent alcohol preference. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1584–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meliska CJ, Bartke A, McGlacken G, Jensen RA. Ethanol, nicotine, amphetamine, and aspartame consumption and preferences in C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;50:619–26. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CF, Lynch WJ. Alcohol preferring (P) rats as a model for examining sex differences in alcohol use disorder and its treatment. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;132:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance DM. Sex differences in the hypothalamic regulation of feeding behavior in the rat. Adv Psychobiol. 1976;3:75–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priddy BM, Carmack SA, Thomas LC, Vendruscolo JC, Koob GF, Vendruscolo LF. Sex, strain, and estrous cycle influences on alcohol drinking in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2017;152:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall CL, Roberts JS, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Mattson ME. Telescoping of landmark events associated with drinking: a gender comparison. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:252–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm-Sapyta NL, Francis R, MacDonald A, Keistler C, O’Neill L, Kuhn CM. Effect of sex on ethanol consumption and conditioned taste aversion in adolescent and adult rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231:1831–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3319-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Anthenelli RM, Bucholz KK, Hesselbrock VM, Tipp J. The time course of development of alcohol-related problems in men and women. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:218–25. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Daeppen JB, Tipp JE, Hesselbrock M, Bucholz KK. The clinical course of alcohol-related problems in alcohol dependent and nonalcohol dependent drinking women and men. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:581–90. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrett-Field L, Butler TR, Reynolds AR, Berry JN, Prendergast MA. Sex differences in neuroadaptation to alcohol and withdrawal neurotoxicity. Pflugers Arch. 2013;465:643–54. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoelder M, Hesseling P, Baars AM, Lozeman-van ’t Klooster JG, Rotte MD, Vanderschuren LJ, Lesscher HM. Individual Variation in Alcohol Intake Predicts Reinforcement, Motivation, and Compulsive Alcohol Use in Rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:2427–37. doi: 10.1111/acer.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haaren F, Anderson K. Sex differences in schedule-induced alcohol consumption. Alcohol. 1994;11:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Social consequences of ethanol: Impact of age, stress, and prior history of ethanol exposure. Physiol Behav. 2015;148:145–50. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengeliene V, Vollmayr B, Henn FA, Spanagel R. Voluntary alcohol intake in two rat lines selectively bred for learned helpless and non-helpless behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;178:125–32. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter-O’Hagen C, Varlinskaya E, Spear L. Sex differences in ethanol intake and sensitivity to aversive effects during adolescence and adulthood. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:547–54. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade GN, Zucker I. Hormonal and developmental influences on rat saccharin preferences. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1969;69:291–300. doi: 10.1037/h0028208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade GN, Zucker I. Development of hormonal control over food intake and body weight in female rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1970;70:213–20. doi: 10.1037/h0028713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. 2014 http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/