Abstract

Romantic involvement and mental health are dynamically linked, but this interplay can vary across the life course in ways that speak to the social and psychological underpinnings of healthy development. To explore this variation, this study examined how romantic involvement was associated with trajectories of depressive symptomatology across the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. Growth mixture modeling of data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health identified trajectories of depressive symptomatology as teens grew into their late 20s and early 30s (n = 8,712). Multinomial logistic techniques regressed these trajectories on adolescent and young adult romantic experiences. Adolescent dating was associated with increased depressive symptoms early on, particularly for girls, but this risk faded over time. For both boys and girls, trajectories of decreasing symptoms were associated with young adult unions but also the coupling of adolescent dating with young adult singlehood.

Keywords: romantic involvement, depressive symptoms, transition to adulthood

Adolescents who partner romantically with the opposite gender often demonstrate higher levels of depressive symptomatology than those who do not, but adults who partner romantically with the opposite gender often demonstrate better mental health than those who are single (Umberson, Thomeer and Williams 2013; Joyner and Udry 2000; Umberson and Williams 1999). This “flip” in the link between heterosexual romantic involvement and mental health suggests a dynamic pattern in which intertwined trajectories of psychosocial maturation and relational experience allow the balance between the costs and benefits of romance to gradually shift across stages of the life course. The added layer of complexity is that gender differentiates romantic involvement, mental health, and the links between the two. Indeed, girls experience more costs from romantic involvement early on and men experience more benefits from involvement later on in ways that create and stabilize gender disparities in mental health favoring boys and men from adolescence into adulthood (Thomeer, Umberson, and Pudrovska 2013; Simon 2002; Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001; Joyner and Udry 2000).

This study connects the dots in this life course framework of interpersonal relations, personal functioning, and population disparities in mental health by tracking how romantic involvement in adolescence, union formation in young adulthood (i.e., marriage, cohabitation), and continuity and change between the two factor into trajectories of depressive symptomatology as adolescent girls and boys grow up into adult women and men. We do so by extending earlier research on adolescence (e.g., Joyner and Udry 2000) into young adulthood, applying growth mixture modeling to estimate the trajectories of young people in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) for over a decade. Specifically, we test—by gender—whether the initially higher depression of adolescent daters persisted or declined as adolescent dating evolved into young adult union formation.

The value of this line of research is that it helps to build the theoretical scaffolding for a better understanding of the evolving link between romantic involvement and mental health across the life course. This scaffolding is useful for unpacking how mental health disparities are reinforced or broken down over time and determining whether boys, girls, men, or women are at greatest risk (and why) for depressive symptomatology associated with romantic involvement (Umberson, Crosnoe, and Reczek 2010). By highlighting the transition to adulthood, we focus on a dynamic point between two life course stages that may have particular significance for both mental health and romantic relationships (Crosnoe and Johnson 2011).

BACKGROUND

Tracking Romance and Depression from Adolescence into Young Adulthood

In 2000, an influential study by Joyner and Udry used the first two waves of Add Health to show that adolescents (especially girls) who engaged in romantic activity had elevated levels of depression compared to those who were not romantically involved. This research has been built on by researchers in a variety of fields studying the risks and benefits of adolescent romantic involvement (Soller 2014; Connolly and McIsaac 2011; Meier 2007; Davila et al. 2004; Kuttler and LaGreca 2004; Grello et al. 2003). This literature is notable for two reasons.

First, the gender difference found by Joyner and Udry and others is relevant to the reversal in gender differences in mental health (girls’ advantage replaced by boy’s advantage) in adolescence that persists into adulthood (Cyranowski et al. 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema 1990). Compared to boys, girls are more vulnerable to romantic involvement during adolescence in many ways, including in terms of mental health. This vulnerability is often attributed to their tendency to use what is going on in their relationships as a barometer of self-worth, so that the ups and downs of relationships can be more threatening to them. It also is more generally related to their heightened sensitivity (relative to boys) to interpersonal dynamics (Rudolph and Conley 2005; Giordano 2003). Whatever its origins, this early romance-related disadvantage has troubling implications for women’s mental health across the life course given that much of the gender gap in prevalence of adult depression can be explained by girls’ earlier onset of symptoms (Kessler 2003; Kessler et al. 1993). Less clear is whether these gendered risks of adolescent dating for depressive symptomatology endure enough to contribute to mental health disparities in adulthood or whether they are confined to adolescence.

Second, this dating risk often found in studies of adolescents is in stark contrast with the clear advantages of coupling in adulthood. A vast literature recognizes the mental health benefits of adult union formation, especially marriage (Williams 2003; Waite and Gallagher 2000). Married adults enjoy better mental health than never married and formerly married adults, with similar advantages extending to the most common type of partnering in young adulthood: cohabitation. These advantages favor men, for whom romantic relationships are more likely to be their primary form of social support (Williams 2003; Simon 2002; Umberson et al. 1996). The well-established association between romantic involvement and mental health in adulthood suggests that, at some point between adolescence and adulthood, the nature of the relationship between romantic involvement and depressive symptomatology changes, likely because the nature of romantic involvement itself is evolving. As adolescents transition into adulthood, therefore, they enter a life stage in which romantic relationships will carry positive, rather than negative, implications for their well-being. This connection between early negatives and later positives needs to be unpacked, especially by gender.

Theoretically, the findings of dating risks in adolescence can be conceptualized within a developmental framework that emphasizes the gendered progression of young people through stages of romantic partnership as they gain more experience with relationships and develop more fully in psychosocial maturity. Early on, dating can be volatile and stressful because adolescents are relatively immature and inexperienced, not to mention the sensation-seeking drive related to brain development that is a hallmark of adolescence. Adolescents ascribe stronger emotions to relationships than to other arenas of their social life, such as school or family (Crosnoe and Johnson 2011; Silk, Steinberg, and Morris 2003; Larson, Clore, and Wood 1999). Because girls have more of an emotional stake in their relationships in general than boys, dating can be a minefield for them. Adolescent boys, on the other hand, gain support and maintenance from relationships that they may not receive elsewhere. Thus, in adolescence, relationships may be a more consistent boon for boys’ mental health (that is, they derive more social and emotional support from their relationships than girls) and more of a mixed bag for girls (Giordano, Longmore, and Manning 2006; Giordano 2003; Nolen-Hoeksema 1994). As adolescents mature, however, they develop psychosocial skills and gain romantic experience, allowing for more successful management of the volatility, stress, and emotion of relationships. Potentially, these developing skills enable young people to forge deeper and longer-lasting relationships and to derive more benefits from them (Collins, Welsh, and Furman 2009; Brown 1999). As they get older, therefore, girls may gain the capability to handle relationship pressures while boys likely grow in their ability to give as partners. The risks associated with relationships for girls may then decrease, and they may enjoy more consistent benefits just as boys already have. Across developmental time, therefore, romantic relationships may become less detrimental to mental health and eventually health-promoting as the benefits balance the costs, with such changes being most evident among girls.

This developmental framework captures a life course process, and so it deserves to be tested in a life course approach. To be more specific, any dating experience is simply one point along a much longer life course trajectory of adjustment and functioning shaped by the interplay of developmental capacities and social contexts. These trajectories are often highly cumulative, but their direction and level can be altered and deflected when young people undergo life course transitions, or changes in setting or stage that usher in new norms, social expectations, and opportunities (Collins et al. 2009; Giordano 2003). Thus, we can think of adolescent dating within a lifelong trajectory of romantic involvement, with changes in the course of that trajectory anchored in major life transitions and differentiated by gender. To capture this life course dynamic, one approach is to track what happens to adolescent daters as they transition to young adulthood, now considered a momentous transition in the life course overall that connects early experience to future prospects (Institute of Medicine, 2014; Hogan and Astone 1986).

If adolescence is a stage in which youth are slowly developing the experience and skills to derive more benefit from romantic involvement, then young adulthood would likely be time when the benefits begin to outweigh the costs. As adolescents navigate this transition, begin occupying adult roles, and engage in union formation, they are entering a life stage associated with the exploration of relationship possibilities, including a growing emphasis on more committed relationships such as marriage and cohabitation (Collins and vanDulmen 2006). This transition, therefore, is when the general course of maturation will magnify the early benefits of romantic relationships for boys and counteract the early risks of such relationships for girls. As a result, both boys and girls will be better equipped to enter unions that they, and others, view as markers of being an adult. This perceived “achievement” can then support their socioemotional adjustment (Collins et al. 2009; Meier and Allen 2009; Raley, Crissey, and Muller 2007). At the same time that these relationship trajectories are unfolding, mental health trajectories are also changing, often in the form of improved psychological functioning as young people move farther away from the social turbulence and developmental stress of adolescence that is especially troubling to girls (Steinberg 2005; Schulenberg, Sameroff, and Cicchetti 2004). Thus, as adolescents enter young adulthood, they have the capacity and drive to form more stable partnerships, and they experience a general recovery in mental health. These two trajectories are likely intertwined, as the kinds of relationships that form as adolescents become young adults and move past adolescent dating (e.g., more mature dating relationships, more committed partnerships like marriage and cohabitation) foster better mental health and vice versa (Musick and Bumpass 2012).

The connection between dating experiences in adolescence and varied young adult relationship statuses that build on adolescent dating should, therefore, be highlighted when looking across the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. What does dating in adolescence lead to, and how does the continuity and change of romantic experiences across the transition to adulthood shape trajectories of depressive symptomatology? Answering these questions requires close attention to gender, given the potential for the maturation of girls and their romantic partners to induce more change across this transition in how they experience these relationships, relative to boys.

Study Aims

Our life course approach focuses on the interplay between psychosocial maturation and relationship experience and its role in the gendered dynamic links between romantic involvement and depressive symptomatology from adolescence into adulthood. This general framework leads to two specific aims.

The first aim is to examine whether the mental health risks of adolescent dating persist as young people transition to adulthood. Is the increase in depressive symptomatology associated with adolescent dating a short-term state or something that carries over into long-term trajectories? To address this question, we look at trajectories of depressive symptomatology for adolescent boys and girls who were and were not romantically involved during high school. The hypothesis is that, as adolescents mature into young adults, they will overcome the stressors of early dating and recover to the point that they no longer differ from adolescents who did not date. We expect, therefore, that adolescents who date will experience trajectories of depressive symptomatology that are high in adolescence but decline across the transition to adulthood. Given the heightened relationship risks of girls early on, this recovery should be more pronounced for them.

The second aim is to highlight how different dimensions of young adult union formation connect adolescent dating and depressive trajectories. Does the potential lingering of or recovery from the mental health risks of adolescent dating into young adulthood vary according to the kinds of young adult relationship experiences into which adolescent dating leads? To investigate whether later romantic involvement offsets the initial costs of early romantic involvement, we examine the romantic histories of boys and girls from adolescence into young adulthood. The hypothesis is that, as young people progressively gain more romantic experience, they will be better equipped to enjoy the benefits of romantic involvement and have healthier trajectories of depressive symptomatology. More specifically, the most positive changes in mental health (e.g., declining trajectories of depressive symptoms) are expected to occur when dating in adolescence is followed by union formation (e.g., cohabitation and marriage) in young adulthood. Given the heightened relationship benefits of boys later on, this progression should be more important for them; in other words, they will be more likely to face an uptick in depressive symptoms if adolescent dating is followed by young adult singlehood.

DATA AND METHODS

Data

Add Health followed a nationally representative sample of adolescents into young adulthood over four waves (Harris et al., 2009). It launched in 1994 with an in-school survey of 90,118 students in 132 middle and high schools across the U.S. This survey created a sampling frame for the nationally representative sample of 20,745 students in the Wave I in-home interviews in 1995, which then led to additional in-home interviews in 1996 (Wave II; n = 14,738, with Wave I high school seniors excluded), 2001–2002 (Wave III; n = 15,197, with Wave I high school seniors brought back in), and 2007–2008 (Wave IV; n = 15,701). The age ranges across waves were: 11 to 18 (Wave I), 12 to 18 (Wave II), 18 to 26 (Wave III), and 24 to 32 (Wave IV).

Following Joyner and Udry (2000), the analytical sample for this study started with all adolescents who were between the ages of 12 and 17 at Wave I. We further narrowed the sample to those who persisted through Waves I, II, III, and IV and had valid longitudinal sampling weights (necessary to adjust for study design effects but also to correct for differential attrition across waves). The final study sample included 8,712 adolescents. As described shortly, all item-level missingness was estimated through multiple imputation.

Measures

Depressive symptomatology

Add Health included a modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) in all waves (Perreira et al. 2005). In each wave, youth reported the frequency of nine feelings in the past week (e.g., “You felt that you could not shake off the blues, even with help from your family and your friends,” “You felt sad”). Responses, which ranged from zero (never or rarely) to three (most of the time or all of the time), were summed into a 27-point scale of escalating symptomatology (average Cronbach’s α = .58). As described in the plan of analyses, the four CES-D measures were combined across waves through growth mixture modeling.

Romantic involvement

In adolescence, the binary romantic involvement variable from Joyner and Udry’s (2000) study was based on self-reports of having either a romantic or liked relationship in Wave I (1 = romantically involved). In young adulthood, relationship status was operationalized in a more complex way through dummy variables for whether the young person was married, cohabiting but not married, dating, or single (Cavanagh 2011). Because the binary nature of the variables did not lend themselves to growth curve modeling, we gauged relationship histories across adolescence and into young adulthood by cross-classifying the two sets of romantic involvement variables into a series of categories: romantically involved in adolescence to married in young adulthood, romantically involved in adolescence to cohabiting in young adulthood, romantically involved in adolescence to dating in young adulthood, romantically involved in adolescence to single in young adulthood, not romantically involved in adolescence to married in young adulthood, not romantically involved in adolescence to cohabiting in young adulthood, not romantically involved in adolescence to dating in young adulthood, and not romantically involved in adolescence to single in young adulthood.

Covariates

Based on the Joyner and Udry (2000) study, several controls were measured to account for sociodemographic position and possible spuriousness: gender (1 = female), age, race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic, other/multi-racial), family structure (1 = lived with both biological parents at Wave I, 0 = other family form), and parent education (an ordinal variable ranging from 1, less than high school, to 5, post-college degree). Age at Wave I was centered around its mean to avoid multicollinearity (Jaccard, Turrisi, and Wan 1990). Age at Wave I was also squared and included as an additional covariate to account for non-linear age effects on changes in depression (Joyner and Udry 2000).

Analytical Strategy

The first step was to identify trajectories of depressive symptomatology from adolescence into young adulthood. We were interested in different types of trajectories—the most common forms that trajectories took in the population rather than the specific trajectories experienced by each individual person. This approach called for growth mixture modeling (GMM), a type of structural equation model that can be estimated in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 2006). This technique reflects the theory that several categories of trajectories may occur within a population and identifies major heterogeneities in growth curves in a sample. Here, GMM produced a categorical variable of depressive symptomatology trajectories, grouping cases according to the various types of trajectories respondents followed from Waves I to IV. The appropriate number of categories (or classes) was determined through several criteria, including a loglikelihood-based test, Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and sample size adjusted BIC (ABIC). The dependent variable in all subsequent analyses was the class of depressive trajectory.

The second step was to estimate multinomial logistic models in which the categories of depressive symptomatology trajectory (derived from GMM) were regressed on various stage-specific and cross-stage measures of romantic involvement. These analyses, which were performed in Stata (StataCorp 2011), generated relative risk ratios (RRR) of “membership” in each category of depressive symptomatology trajectory. To get at the persistence or fade of links between adolescent romance and depressive symptoms, Model 1 regressed the adolescent-to-young adulthood trajectory categories on Wave I romantic involvement. To get at whether these dynamic patterns varied according to the young adult experiences that followed adolescent dating, Models 2 to 3 added the young adult romantic involvement variables and then the set of variables that combined adolescent relationship status with all young adult relationship statuses.

These multinomial logistic regression models were estimated for the full analytical sample and then separately by gender. Gender differences were also formally tested by estimating interaction effects. We present results for gender-stratified models only in the case of statistically significant gender differences. Missing data were accounted for with multiple imputation, which estimated missing values for all youth based on simulated versions. The STATA suite of mi commands created ten imputed data sets and then averaged results across these data sets for final estimates (StataCorp 2011).

RESULTS

Romantic Involvement in Adolescence and Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

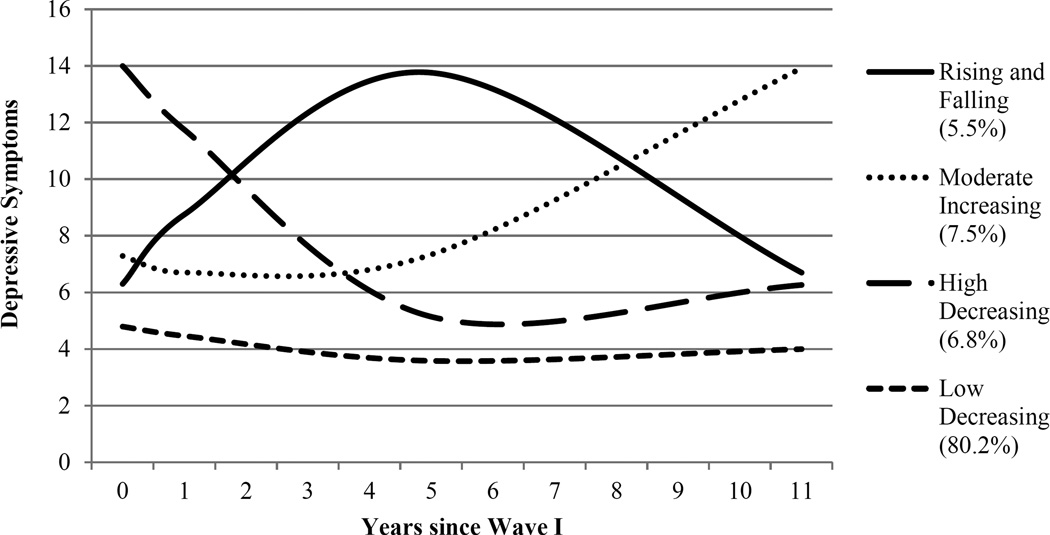

Table 1 provides the criteria used to determine how many types of Wave I-IV trajectories of depressive symptomatology existed in the sample. For log-likelihood, BIC, and ABIC measures of fit, smaller absolute values indicate better model fit; thus, the relative change from the k-class to k-1-class is important. A Lo-Mendell Rubin (LMR) adjusted likelihood ratio test was also evaluated as a test of model fit. A significant p-value on the LMR test suggests that the k-class model is better-fitting than the k-1-class model. Model fit statistics, moreover, were evaluated in conjunction with the usefulness of the model classes. In this case, the four class model was the best fit of the data according to the LMR p-value and the relative changes in log-likelihood, BIC, and ABIC values. In addition to model fit, the four identified trajectories presented substantively meaningful and useful classes (see Figure 1). The four classes included 1) adolescents with moderate levels of depressive symptoms that increased slightly and then improved during the transition to young adulthood (labeled Rising and Falling), 2) adolescents with moderate levels of depressive symptoms that increased more sharply during the transition to young adulthood (labeled Moderate Increasing), 3) adolescents with high levels of depressive symptoms that decreased sharply during the transition to young adulthood (labeled High Decreasing), 4) and adolescents with low levels of depressive symptoms that decreased during the transition to young adulthood (labeled Low Decreasing). Low Decreasing was the majority group, accounting for approximately 80% of the sample.

Table 1.

GMM criteria for class determination

| 1 Class | 2 Classes | 3 Classes | 4 Classes | 5 Classes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loglikelihood | –95281 | –94407 | –93955 | –93382 | –93175 |

| # parameters | 10 | 14 | 18 | 22 | 26 |

| BIC | 190653 | 188942 | 188073 | 186963 | 186586 |

| ABIC | 190621 | 188897 | 188016 | 186893 | 186504 |

| LMR p-value | .879 | .888 | .857 | .867 | |

| Entropy | .0000 | .0001 | .0001 | .0691 | |

| Distribution of respondents into identified classes |

90.1%, 9.1% |

87.0%, 8.7%, 4.2% |

5.1%, 7.9%, 6.1%, 80.8% |

5.5%, 79.8%, 4.4%, 4.1%, 6.2% |

n = 8,712

Figure 1.

Four classes of depressive trajectories from adolescence into young adulthood

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the young people in each class. Adolescents in the High Decreasing trajectory had the highest percentage of romantically involved adolescents (70%), and the Moderate Increasing and Low Decreasing trajectories had the lowest percentage of romantically involved adolescents (50%). Variation was also seen across trajectories for romantic involvement in adulthood. For example, approximately 36 to 37% of the High Decreasing and Low Decreasing trajectory were married in young adulthood, whereas only about 24 to 27% of the Rising and Falling and Moderate Increasing trajectories were married.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics by depressive trajectory

| Rising and Falling |

Moderate Increasing |

High Decreasing |

Low Decreasing |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 478) | (n = 644) | (n = 596) | (n = 6,994) | |||||

| Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | |||||

| Depression | ||||||||

| Wave I | 6.81 | (4.28) | 7.23 | (4.17) | 14.96 | (3.51) | 4.86 | (3.20) |

| Wave II | 8.38 | (4.49) | 7.50 | (4.35) | 12.65 | (4.49) | 4.90 | (3.48) |

| Wave III | 14.70 | (3.12) | 7.31 | (4.54) | 5.30 | (3.75) | 3.63 | (2.86) |

| Wave IV | 6.88 | (3.72) | 14.67 | (3.30) | 6.40 | (3.54) | 4.09 | (2.75) |

| Romantic Involvement | ||||||||

| Involved Wave I | 50.63 | 49.84 | 69.97 | 49.61 | ||||

| Married Wave IV | 27.06 | 23.90 | 36.81 | 36.44 | ||||

| Cohabiting Wave IV | 44.23 | 48.91 | 38.09 | 38.65 | ||||

| Dating Wave IV | 20.75 | 18.54 | 19.80 | 19.07 | ||||

| Single Wave IV | 10.90 | 11.37 | 8.39 | 9.18 | ||||

| Romantic Trajectory | ||||||||

| Involved Wave I - Married Wave IV | 12.58 | 11.22 | 25.80 | 17.83 | ||||

| Involved Wave I - Cohabiting Wave IV | 23.43 | 27.33 | 28.36 | 20.82 | ||||

| Involved Wave I - Dating Wave IV | 11.51 | 8.54 | 12.08 | 9.01 | ||||

| Involved Wave I - Single Wave IV | 3.56 | 3.11 | 5.03 | 2.36 | ||||

| Not involved Wave I - Married Wave IV | 12.90 | 11.21 | 9.55 | 16.81 | ||||

| Not involved Wave I - Cohabiting Wave IV | 20.75 | 21.50 | 9.73 | 17.80 | ||||

| Not involved Wave I - Dating Wave IV | 9.22 | 9.97 | 7.72 | 10.05 | ||||

| Not involved Wave I - Single Wave IV | 7.34 | 8.26 | 3.36 | 6.81 | ||||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Female | 67.36 | 68.17 | 77.85 | 51.36 | ||||

| Age (Wave I) | 14.98 | (1.42) | 14.92 | (1.42) | 15.43 | (1.31) | 15.02 | (1.44) |

| Age Squared | 226.38 | (42.08) | 224.56 | (42.21) | 239.79 | (39.68) | 227.59 | (42.89) |

| Parent Education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 15.43 | 17.30 | 16.25 | 10.47 | ||||

| High school graduate | 28.91 | 35.44 | 31.61 | 28.45 | ||||

| Some higher education | 22.39 | 20.97 | 21.79 | 20.35 | ||||

| College graduate | 23.48 | 17.64 | 19.29 | 26.25 | ||||

| Post-college degree-earner | 9.78 | 8.65 | 11.07 | 14.48 | ||||

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 44.35 | 50.78 | 48.66 | 56.43 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 27.62 | 23.60 | 19.97 | 18.32 | ||||

| Hispanic | 16.95 | 14.44 | 18.62 | 14.48 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 4.39 | 4.97 | 6.54 | 5.55 | ||||

| Other/multi-racial | 6.69 | 6.21 | 6.21 | 5.22 | ||||

| Two-biological parent household (Wave I) | 49.79 | 46.89 | 46.31 | 58.79 | ||||

Our first aim was to examine how adolescent romantic involvement was related to trajectories of depressive symptomatology from adolescence into young adulthood. In this spirit, multinomial logistic models regressed the classes of trajectories of depressive symptomatology on adolescent romantic status and the covariates. The results in Table 3 are for models in which the Low Decreasing class served as the reference for the dummy variable outcomes, although all pairwise comparisons were estimated in ancillary models and are discussed in the text.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression of depressive trajectory on romantic relationship involvement in adolescence

|

RRR (SE) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rising and Falling |

Moderate Increasing |

High Decreasing |

|

| Full Sample | |||

| Involved Wave I | 1.051 | 1.137 | 1.907*** |

| (.140) | (.133) | (.250) | |

| Girls | |||

| Involved Wave I | 1.086 | 1.265 | 2.468*** |

| (.181) | (.180) | (.374) | |

| Boys | |||

| Involved Wave I | .991 | .948 | 1.122 |

| (.227) | (.192) | (.287) | |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

Low Decreasing was the reference for depressive trajectory. All models controlled for age, age squared, parent’s education, race-ethnicity, and family structure in adolescence. Full sample model controlled for gender.

In general, romantic involvement in adolescence was associated with a significantly higher risk of membership in the High Decreasing class (p < .001) as compared to the Low Decreasing class. Romantically involved adolescents at Wave I, in fact, were nearly two times more likely to follow the High Decreasing trajectory than the Low Decreasing trajectory. This pattern is consistent with prior work in Add Health and other data sets finding that romantic involvement in adolescence was associated with higher depressive symptoms (Meier 2007; Davila et al. 2004; Welsh, Grello, and Harper 2003; Joyner and Udry 2000). Importantly, however, the High Decreasing trajectory was characterized by a sharp decline in depressive symptoms as the adolescent transitioned to young adulthood.

When stratifying by gender, adolescent girls had similar results as the full sample, with increased risk of a High Decreasing trajectory (p < .001) as compared to a Low Decreasing trajectory. Among boys, however, adolescent romantic involvement was not associated with their trajectories of depressive symptomatology into young adulthood, echoing the finding of Joyner and Udry (2000) and others (Meier 2007; Davila et al. 2004) that boys were less at risk than girls from early dating. According to the interaction effects estimated (results not shown), this gender difference was statistically significant (p < .05).

In line with our first hypothesis, therefore, the negative implications of adolescent dating were not manifested over time in trajectories of depressive symptoms into young adulthood. This pattern better characterized the experiences of girls than boys.

The Role of Young Adult Romantic Involvement

Our second aim was to examine how links between adolescent dating and trajectories of depressive symptomatology into young adulthood varied according to relationship histories stretching between adolescence and young adulthood. To pursue this aim, we estimated a new set of multinomial logistic models, switching out adolescent dating status for the dummy variables connecting adolescent romantic involvement to young adult romantic involvement. Before presenting these results, we lay out some context by first describing how young adult romantic involvement was associated with trajectories of depressive symptomatology, regardless of the adolescent dating statuses that might have preceded the young adult involvement (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression of depressive trajectory on romantic relationship involvement in young adulthood

|

RRR (SE) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rising and Falling |

Moderate Increasing |

High Decreasing |

|

| Full Sample | |||

| Married Wave IV | .740 | .323* | .690 |

| (.349) | (.153) | (.374) | |

| Cohabiting Wave IV | .936 | .438 | .617 |

| (.416) | (.191) | (.320) | |

| Dating Wave IV | .915 | .320* | .736 |

| (.416) | (.143) | (.386) | |

| Involved Wave I | 1.036 | 1.161 | 1.932*** |

| (.140) | (.137) | (.257) | |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Low Decreasing was the reference for depressive trajectory. Single is the reference group for romantic relationship involvement in Wave IV. All models controlled for gender, age, age squared, parent’s education, race-ethnicity, and family structure in adolescence.

For the full sample, being married or dating in young adulthood (relative to being single) was associated with lower risk of being in the Moderate Increasing trajectory than the Low Decreasing trajectory (p < .05). These associations were consistent across men and women; and, no significant interaction effects were found. In sum, romantic involvement in young adulthood appeared to protect against increasing depressive symptomatology from adolescence into young adulthood for both genders. On the other hand, decreasing depressive symptomatology (i.e, the High Decreasing trajectory) was only associated with adolescent romantic involvement, independent of young adult relationship status (p < .001).

Turning to the focal models that combined romantic involvement across adolescence and young adulthood, Table 5 reveals that, in general, being romantically involved in adolescence and then single at Wave IV was associated with higher odds of following the High Decreasing trajectory (i.e., doing less well initially but better over time) than following the Low Decreasing trajectory, relative to the reference group of those who were single at both waves. No significant gender differences were observed.

Table 5.

Multinomial logistic regression of depressive trajectory on match/mismatch of romantic relationship involvement across adolescence to young adulthood

|

RRR (SE) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rising and Falling |

Moderate Increasing |

High Decreasing |

|

| Full Sample | |||

| Involved WI - married WIV | .817 | .436 | 1.471 |

| (.412) | (.235) | (.861) | |

| Involved WI - cohabiting WIV | 1.061 | .692 | 1.451 |

| (.533) | (.361) | (.848) | |

| Involved WI - dating WIV | 1.305 | .482 | 1.623 |

| (.683) | (.261) | (.969) | |

| Involved WI - single WIV | 1.496 | 2.215 | 2.403* |

| (.623) | (.970) | (.833) | |

| Not involved WI - married WIV | .899 | .461 | .843 |

| (.494) | (.260) | (.537) | |

| Not involved WI - cohabiting WIV | 1.148 | .565 | .714 |

| (.580) | (.295) | (.430) | |

| Not involved WI - dating WIV | .874 | .437 | .975 |

| (.464) | (.235) | (.597) | |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Low Decreasing was the reference for depressive trajectory. Not involved WI - Single WIV is the reference group for romantic relationship involvement match/mismatch. All models controlled for gender, age, age squared, parent’s education, race-ethnicity, and family structure in adolescence.

These results were inconsistent with our hypothesis that progressive romantic involvement (i.e., dating followed by union formation) would be associated with trajectories characterized by declining depressive symptoms across the transition to adulthood. Instead, a less incremental history of growing involvement (e.g., romantic involvement in adolescence followed by singlehood in young adulthood) was associated with the clearest “recovery” patterns. This finding was consistent across genders, suggesting that both girls and boys were best able to recover from depressive symptoms associated with romantic involvement in adolescence when they did not partner in young adulthood.

Sensitivity Analyses

Two sensitivity analyses were performed to supplement our findings. First, the main analyses operationalized adolescent romantic involvement using data from Wave I in order to mirror the previous work on adolescent romance and depression with these data (Joyner and Udry 2000). We also expanded the adolescent romantic involvement measure to include adolescents who reported a romantic or liked relationship in either Wave I or Wave II. The results were consistent with the findings presented so far with one exception. When accounting for romantic involvement in either Wave I or Wave II, girls who had dated in adolescence and were then single in young adulthood did not have significantly higher risk of being in the High Decreasing class than the Low Decreasing class. This one discrepancy suggests that the tendency for singlehood in young adulthood to condition links between adolescent dating and a recovery in mental health was weaker for girls who continuously dated in adolescence than those with more sporadic dating patterns.

Second, to explore bidirectionality between romantic involvement and depressive symptoms, we performed a cross-lagged analysis comparing the pathway between adolescent mental health and young adult romantic involvement with the pathway between adolescent romantic involvement and young adult mental health. No significant pathways emerged between adolescent romantic relationships and young adult mental health, consistent with our results showing a waning risk of adolescent dating for mental health across the transition to adulthood. A significant, inverse pathway did emerge between adolescent mental health and young adult marriage, which suggests that some young adults who settled into marriage were already healthy (e.g., Waite 1995). This pathway, therefore, qualified our results suggesting marriage benefits.

DISCUSSION

Romantic involvement is something that progresses and evolves over time, just as mental health is an ongoing, unfolding experience. Life course approaches emphasize the intertwining of such life trajectories, which, in this case, means considering how the two are related to each other across stages of life. Such an approach can help to elucidate why a behavioral experience or psychological state can represent health risks at one stage and healthy functioning at another. Dating in adolescence is often followed by a transition to committed partnerships in young adulthood. Independent of one or the other, the progression of the two can also matter for whether mental health improves or declines during the same period. What does this intertwining tell us about both romantic involvement and mental health? Working from our developmentally oriented framework rooted in past research across disciplines (Collins et al. 2009; Schulenberg et al. 2004; Joyner and Udry 2000), we tested two hypotheses to gain insights into this question

Consistent with our first hypothesis, the negative implications of romantic involvement in adolescence did not persist into young adulthood. Although dating in adolescence was associated with increased depressive symptomatology, it was not associated with elevated symptomatology in young adulthood. In other words, just because dating in adolescence might have posed short-term risks, it did not necessarily lead to risky trajectories over the long haul. At the same time, we did not find support for our second hypothesis about links between progressive romantic histories and declining depressive trajectories. Instead, girls and boys showed patterns of recovery when their adolescent romantic involvement was followed by being single in young adulthood. Although the risks of adolescent dating faded over time, youth may have been best suited for recovery when they were not partnering but instead focusing on other developmental tasks and life goals (e.g., educational and occupational attainment, independent living).

Recall that gender was a major component of our developmental framework and associated hypotheses. The results of our analyses supported our expectations that girls would be more likely to have decreasing dating-related depressive symptomatology across the transition to adulthood. At the same time, our results did not suggest that boys, who were less at risk than girls in adolescence, would also be more protected against depressive symptomatology by romantic involvement in adulthood. Instead, no gender differences emerged in the associations between young adulthood romantic experiences and increasing depressive symptomatology. Adolescent relationships, therefore, seemed to be more imbalanced towards risks for girls than boys, but only early on. The transition to young adulthood, therefore, could be a significant trigger changing the way that romance is experienced and construed.

This gendered component of the association between mental health and romantic involvement, particularly as it develops over time, is an area for future exploration. In other words, the question remains whether the early advantages of boys (and young men) explain the gap in mental health disparities by gender across the life course. Researchers should seek a more comprehensive understanding of how romantic involvement and mental health trajectories intertwine and mutually influence each other as relationships evolve and mature, going beyond to the gender of the individual person to the gender composition of the couple (i.e., differences and similarities between opposite-sex and same-sex relationships) (Liu, Reczek, and Brown 2013; Wight, LeBlanc, and Badgett 2013). Likewise, following the call of Hill and Needham (2013), researchers should not only test gender differences in mental health across the life course. They should also develop more thorough theoretical frameworks to analyze how and why men and women’s responses to stress are associated with different mental health outcomes. Although men’s depressive symptoms may not be as responsive to relationship-induced stress as women’s, men may still be influenced by these stressors. When studying the mental health gap across the life course, therefore, scholars should attempt a deeper conceptualization of stress responses and, in doing so, build theory for future work.

Importantly, although we documented a dynamic link between mental health and romantic relationships across adolescence into young adulthood, our findings do not speak to the mechanisms by which these experiences are associated. Relationships are defined not only by statuses but also by quality, partner characteristics, sexual behavior, interactions, and transitions, all of which influence mental health (Thomeer et al. 2013; Simon and Barrett 2010; Umberson et al. 2006). These relationships building blocks likely speak to each other in ways that condition the experiences of young people’s romantic lives. Our developmental framework posited that, across the transition to adulthood, young people gain experience in relationships that allow them to maximize the benefits they receive from romantic involvement. Young people, however, may—or may not—gain this experience in relationships characterized by poor quality, unsupportive partners, early sexual debut, negative interactions, or instability. Such experiences undoubtedly influence mental health trajectories in important ways and could have increased meaning as young people transition to adulthood and ascribe greater importance to partnership. Across this transition, therefore, relationship quality and partnership choice can have increased significance for mental health—in ways that differ by gender (Simon and Barrett 2010). By focusing only on relationship status in our analyses, we did not capture the everyday realities or general states of relationships. Future research should build on our findings by taking a closer look at the underlying processes through which the associations between romantic relationships and mental health develop and change during the crucial transition to adulthood.

When researchers focus on either adolescent or adult populations, they often fall short of understanding the overarching cumulative effects of how, for example, romantic involvement shapes mental health. A life course approach, therefore, bridges the gaps among childhood, adolescence, and adulthood literatures and highlights how implications of experiences and statuses accumulate and cascade into the future (Umberson et al. 2010). In this vein, we took a life course approach in order to connect the literatures on mental health and romantic involvement between adolescent and adult populations. Our conclusions support the necessity of situating young adult relationships in the context of adolescent relationship experiences, and looking forward, we encourage further study of how and why early life mental health disadvantages associated with romantic relationships persist into later life.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. The authors acknowledge the generous support of grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 HD042849) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. This research also received support from the grant, 5 T32 HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Biographies

Julie Skalamera Olson is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Sociology and a graduate student trainee in the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. As a social demographer and life course sociologist, her research agenda focuses on health disparities from childhood through adulthood.

Robert L. Crosnoe is the C.B. Smith, Sr. Centennial Chair #4 at the University of Texas at Austin, where he chairs the Department of Sociology and is a research associate of the Population Research Center. His main field of interest is child and adolescent development, with emphasis on social-psychological approaches to education and health and how they can illuminate socioeconomic and immigration-related inequalities in the United States. His current work focuses on the social experiences, mental health, and health behavior of high school students from a variety of family backgrounds and the early physical health and learning of the young children of Mexican immigrants.

Contributor Information

Julie Skalamera Olson, University of Texas at Austin.

Robert Crosnoe, University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Brown B Bradford. You’re Going with Who? Peer Group Influences on Adolescent Romantic Relationships. In: Furman Wyndol, Brown B Bradford, Feiring Candice., editors. The Development of Romantic Relationships in Adolescence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 291–329. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh Shannon. Early Pubertal Timing and Union Formation Behaviors of Young Women. Social Forces. 2011;89:1217–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Collins W Andrew, van Dulmen Manfred. Friendships and Romance in Early Adulthood: Assessing Distinctiveness in Close Relationships. In: Arnett Jeffrey Jenson, Tanner Jennifer Lynn., editors. Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Collins W Andrew, Welsh Deborah P, Furman Wyndol. Adolescent Romantic Relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Jennifer, McIsaac Caroline. Romantic Relationships in Adolescence. In: Underwood Marion K, Rosen Lisa H., editors. Social Development: Relationships in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 180–204. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert, Johnson Monica Kirkpatrick. Research on Adolescence in the 21st Century. Annual Review of Sociology. 2011;37:439–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski Jill M, Frank Ellen, Young Elizabeth, Shear Katherine. Adolescent Onset of the Gender Difference in Lifetime Rates of Major Depression: A Theoretical Model. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila Joanne, Steinberg Sara J, Kachadourian Lorig, Cobb Rebecca, Fincham Frank. Romantic Involvement and Depressive Symptoms in Early and Late Adolescence: The Role of Preoccupied Relational Style. Personal Relationships. 2004;11(2):161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano Peggy C. Relationships in Adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano Peggy C, Longmore Monica A, Manning Wendy D. Gender and the Meaning of Adolescent Romantic Relationships: A Focus on Boys. American Sociological Review. 2006;71(2):260–287. [Google Scholar]

- Grello Catherine M, Welsh Deborah P, Harper Melinda S, Dickson Joseph W. Dating and Sexual Relationship Trajectories and Adolescent Functioning. Adolescent and Family Health. 2003;3(3):103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Kathleen Mullan, Halpern Carolyn T, Whitsel Eric, Hussey Jon, Tabor J, Entzel Pamela, Udry J Richard. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2009 Retrieved June 5th 2011. ( http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design)

- Hill Terrence D, Needham Belinda L. Rethinking Gender and Mental Health: A Critical Analysis of Three Propositions. Social Science and Medicine. 2013;92:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Dennis P, Astone Nan Marie. The Transition to Adulthood. Annual Review of Sociology. 1986;12:109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults. Washington, DEC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard James, Turrisi Robert, Wan Choi K. Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner Kara, Udry JRichard. You Don’t Bring Me Anything but Down: Adolescent Romance and Depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(4):369–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C. Epidemiology of Women and Depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;74(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C, McGonagle Katherine A, Swartz Marvin, Blazer Dan G, Nelson Christopher B. Sex and Depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime Prevalence, Chronicity, and Recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser Janice K, Newton Tamara L. Marriage and Health: His and Hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(4):472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttler Ami Flam, La Greca Annette M. Linkages among Adolescent Girls’ Romantic Relationships, Best Friendships, and Peer Networks. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(4):395–414. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson Reed W, Clore Gerald L, Wood Gretchen A. The Emotions of Romantic Relationships: Do They Wreak Havoc on Adolescents? In: Furman Wyndol, Brown B Bradford, Feiring Candice., editors. The Development of Romantic Relationships in Adolescence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Hui, Reczek Corinne, Brown Dustin. Same-Sex Cohabitors and Health: The Role of Race-Ethnicity, Gender, and Socioeconomic Status. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54(1):25–45. doi: 10.1177/0022146512468280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier Ann. Adolescent First Sex and Subsequent Mental Health. American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112(6):1811–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Meier Ann, Allen Gina. Romantic Relationships from Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. The Sociological Quarterly. 2009;50(2):308–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick Kelly, Bumpass Larry. Reexamining the Case for Marriage: Union Formation and Changes in Well-Being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén Linda K, Muthén Bengt O. Mplus User’s Guide. Fourth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema Susan. Sex Differences in Depression. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema Susan. An Interactive Model for the Emergence of Gender Differences in Depression in Adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4(4):519–534. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira Krista M, Deeb-Sossa Natalia, Harris Kathleen Mullan, Bollen Kenneth. What Are We Measuring? An Evaluation of the CES-D across Race/Ethnicity and Immigration Generation. Social Forces. 2005;83(4):1567–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Raley R Kelly, Crissy Sarah, Muller Chandra. Of Sex and Romance: Late Adolescent Relationships and Young Adult Union Formation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(5):1210–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph Karen D, Conley Colleen. The Socioemotional Costs and Benefits of Social-Evaluative Concerns: Do Girls Care Too Much? Journal of Personality. 2005;73:115–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg John E, Sameroff Arnold J, Cicchetti Dante. The Transition to Adulthood as a Critical Juncture in the Course of Psychopathology and Mental Health. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(4):799–806. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk Jennifer S, Steinberg Laurence, Morris Amanda Sheffield. Adolescents’ Emotion Regulation in Daily Life: Links to Depressive Symptoms and Problem Behavior. Child Development. 2003;74(6):1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Robin W. Revisiting the Relationships among Gender, Marital Status, and Mental Health. American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107(4):1065–1096. doi: 10.1086/339225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Robin W, Barrett Anne E. Nonmarital Romantic Relationships and Mental Health in Early Adulthood: Does the Association Differ for Women and Men? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(2):168–182. doi: 10.1177/0022146510372343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soller Brian. Caught in a Bad Romance: Adolescent Romantic Relationships and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2014;55(1):56–72. doi: 10.1177/0022146513520432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg Laurence. Cognitive and Affective Development in Adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer Mieke, Pudrovska Tetyana, Umberson Debra. Marital Processes around Depression: A Gendered Perspective. Society and Mental Health. 2013;3:151–169. doi: 10.1177/2156869313487224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Chen Meichu D, House James S, Hopkins Kristine, Slaten Ellen. The Effect of Social Relationships on Psychological Well-Being: Are Men and Women Really So Different? American Sociological Review. 1996;61(5):837–857. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Williams Kristi. Family Status and Mental Health. In: Aneshensel Carol S, Phelan Jo C., editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Pubs; 1999. pp. 225–253. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Williams Kristi, Powers Daniel A, Liu Hui, Needham Belinda. You Make Me Sick: Marital Quality and Health over the Life Course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:1–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Crosnoe Robert, Reczek Corinne. Social Relationships and Health Behavior across Life Course. Annual Review of Sociology. 2010;36:139–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Thomeer Mieke Beth, Williams Kristi. Family Status and Mental Health: Recent Advances and Future Directions. In: Aneshensel Carol S, Phelan Jo C., editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. 2nd. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Pubs; 2013. pp. 405–431. [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J. Does Marriage Matter? Demography. 1995;32(4):483–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J, Gallagher Maggie. The Case for Marriage: Why Married People are Happier, Healthier, and Better off Financially. New York, NY: Doubleday; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh Deborah P, Grello Catherine M, Harper Melinda S. When Love Hurts: Depression and Adolescent Romantic Relationships. In: Florsheim Paul., editor. Adolescent Romantic Relations and Sexual Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practical Implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2003. pp. 185–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wight Richard G, LeBlanc Allen J, Badgett MV Lee. Same-Sex Legal Marriage and Psychological Well-Being: Findings from the California Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(2):339–346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams Kristi. Has the Future of Marriage Arrived? A Contemporary Examination of Gender, Marriage, and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(4):470–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]