Abstract

Erlotinib is one of the treatment choices for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), regardless of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation status. However, its efficacy for the treatment of patients with NSCLC with EGFR wild type or who are beyond the usage of gefitinib remains controversial. The present study therefore retrospectively assessed the efficacy of erlotinib in patients with wild type EGFR who had previously undergone gefitinib therapy. A total of 222 patients with NSCLC who received chemotherapeutic treatment with erlotinib between July 2007 and February 2013 were evaluated. The background variables, response rates, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival rates were retrospectively analyzed. The male/female ratio of patients was 103/119, and patients had a median age of 63 years (range, 33–95 years). A total of 10 of the 222 patients had clinical stages IIIB/IV, 191 had adenocarcinoma, 5 had large cell carcinoma, 10 had squamous cell carcinoma and 6 had NSCLC of a variety not otherwise specified. The EGFR mutation was positive, wild type or unknown in 95, 52 and 75 patients, respectively. In the 52 patients with EGFR wild type, there were 3 partial responders, 25 with stable disease and 24 with progressive disease, for a response rate of 6% [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.3–15%]. The median PFS of EGFR wild type and positive were 1.1 months (95% CI, 1.04–1.16 months) and 5.42 months (95% CI, 5.43–5.68 months), respectively. The results of the study demonstrated that erlotinib is not sufficiently effective for patients with NSCLC who possess the EGFR wild type status.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, erlotinib, gefitinib, epidermal growth factor receptor, wild type

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of malignancy-associated mortality worldwide (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprises ~80% of all cases, and the majority of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease (2). Systemic chemotherapy (with or without bevacizumab) or tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy currently represent the primary treatment options for prolonging a patient's survival rate and improving their quality of life (3–6). At present, the standard first-line chemotherapy for unselected advanced NSCLC is platinum doublet regimens using a third-generation anti-cancer agent (7,8).

Erlotinib, a small molecule inhibitor of the intracellular tyrosine kinase of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has been approved as second-line therapy for patients with advanced NSCLC in numerous countries. A phase III trial (the BR.21 trial) demonstrated that unselected patients with advanced NSCLC, progressing subsequent to first-line chemotherapy, gained a survival benefit when treated with erlotinib compared with best supportive care (9). At the start of BR.21, EGFR mutations in NSCLC had not yet been identified; therefore, the study included molecularly unselected patients. The discovery and characterization of EGFR mutations in 2004 was a key example of oncogene addiction, associated with a high efficacy of biomarker-driven treatment (10–12). As a result, EGFR TKIs are currently the treatment of choice for patients with EGFR mutations. Several phase III studies have demonstrated that erlotinib and gefitinib are superior to chemotherapy in first-line treatment, but only in EGFR-mutated patients (5,13–15). The value of erlotinib as a second-line and third-line treatment of patients with wild type or unknown EGFR mutation status remains controversial.

In previous years, the Tarceva Italian Lung Optimization (TAILOR) phase III trial demonstrated that chemotherapy was more effective compared with erlotinib for second-line treatment for previously treated patients with NSCLC who possess wild type EGFR tumors (16). The present study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of erlotinib in second-line or more advanced NSCLC, in particular for patients with EGFR wild type status and who received pretreatment with gefitinib.

Patients and methods

Patients

A total of 222 patients with NSCLC received erlotinib treatment as a first-line or further chemotherapy at the National Kyushu Cancer Center (Fukuoka, Japan) between July 2007 and the end of February 2013. Erlotinib therapy was applied for patients who satisfied all the following requirements: Age ≥20 years; pathologically or cytologically diagnosed as exhibiting NSCLC; clinical stage III or IV disease (including IIIA, non-applicable for radical radiotherapy) according to the seventh edition of the ‘tumor, node, metastasis’ classification of lung cancer (17); presenting evaluable lesions (cases without measurable lesions were acceptable); freedom from severe disorders in major organs (bone marrow, heart, lungs, liver and kidneys); without interstitial lung disease (ILD); and laboratory test data at the commencement of treatment indicating a neutrophil count ≥2,000 cells/mm3 (normal range, 3,300–8,600 cells/mm3), a hemoglobin level ≥9.0 g/dl (normal range, 13.7–16.8 g/dl), a platelet count ≥10.0×104 cells/mm3 (normal range, 15.8–34.8×104 cells/mm3), aspartate aminotransferase [normal range 13–30 international units (IU)/l] and alanine aminotransferase (normal range 10–42 IU/l) levels ≤100 IU/l, a total bilirubin level ≤1.5 mg/dl (normal range, 0.4–1.5 mg/dl), a serum creatinine level ≤1.2 mg/dl (normal range, 0.65–1.07 mg/dl) and a peripheral O2 saturation level of ≥90% (normal range, ≥90%). Treatment was provided subsequent to each patient providing written consent on the basis of receiving sufficient information regarding the treatment plan. All patients signed a consent form prior to entry to the study. The present study was approved by the National Kyushu Cancer Center Local Research Ethics Committee.

Treatment and study design

Eligible patients received oral erlotinib at a dose of 150 mg/day until disease progression (PD) or unacceptable toxicity. Dose reductions (in 50-mg decrements) were permitted to manage adverse events associated with erlotinib treatment. If a patient had a confirmed diagnosis of ILD, erlotinib was discontinued immediately.

Evaluation of the response and statistical analysis

Prior to the start of erlotinib therapy, diagnostic imaging with computed tomography scanning was performed to yield baseline information. Tumor response evaluation was scheduled every 6 weeks. Responses to treatment were evaluated using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 (18). The progression free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the start of treatment to PD or mortality. The overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the start of treatment to mortality. The follow-up period concluded on May 31, 2013 for patients either still receiving treatment or beginning to receive the next treatment.

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were produced using the Kaplan-Meier method. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation. Univariate analysis was initially undertaken, followed by Cox's multivariate analysis that included all variables with a significance level of P<0.05, to identify variables associated with a risk of mortality. Analysis of linear correlation was used to evaluate the correlation between two variables; analysis of variance with Dixon's Q-test was used to compare multiple variables. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistics were produced using StatView version 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Table I summarizes the background variables of the 222 patients who received erlotinib in the present study. There were 119 males and 103 females, with a median age of 63 years (range, 33–95 years). The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (19) performance status (PS) was 0–1, 2 and 3–4 in 181, 21 and 20 cases, respectively. The histological types were adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma and NSCLC (NOS; not otherwise specified) in 191, 10, 5 and 16 cases, respectively. The clinical stage was IIIA, IIIB and IV in 1, 15 and 206 cases, respectively. The EGFR mutation status was positive in 95 patients [exon 18 (G719A or G719S) in 3 cases, exon 19 deletion in 47 cases (with T790M in 3 cases), exon 21 (L858R or L861Q) in 43 cases (with T790M in 5 cases) and NOS in 2 cases], wild type in 52 cases and unknown in 75 cases, respectively. A total of 92/222 patients received gefitinib prior to erlotinib treatment. The median follow-up time for the 222 patients who received erlotinib therapy was 858 days (range, 27–4543 days).

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Clinical features | All patients (n=222) | EGFR wild type (n=52) | EGFR mutated (n=95) | EGFR status unknown (n=75) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male/female | 119/103 | 33/19 | 33/62 | 37/38 |

| Age | ||||

| Median (range) | 63 (33–95) | 64 (36–85) | 63 (37–95) | 61 (33–83) |

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0/1/2/3/4 | 63/118/21/15/5 | 17/28/3/3/1 | 38/35/10/8/4 | 8/55/8/4/0 |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Never | 122 | 13 | 55 | 32 |

| Current/former | 100 | 23/16 | 15/25 | 20/23 |

| Histological type | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 191 | 43 | 88 | 60 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 10 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| NSCLC (NOS) | 16 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Stage | ||||

| IIIA/IIIB/IV | 1a/15/206 | 0/7/45 | 1/2/92 | 0/5/70 |

| Prior gefitinib treatment | ||||

| Yes/no | 91/131 | 9/43 | 50/45 | 32/43 |

| Prior regimens | ||||

| 0/1/2/3 or more | 3/55/107 | 0/6/30 | 3/20/32 | 0/9/21/45 |

Unresectable and non-applicable for radiotherapy. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Response and survival analysis of all patients

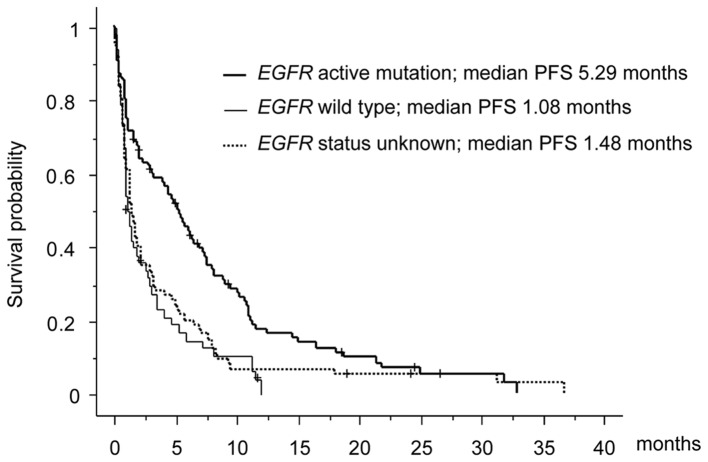

The efficacy was evaluated by each attending physician in accordance with the RECIST criteria, version 1.1. Among the 222 patients who received erlotinib therapy, the best overall response was a partial response (PR) in 31 patients, stable disease (SD) in 101 patients and progressive disease (PD) in 90 patients. The best response rate (RR) of all patients was 14% [95% confidence interval (CI), 10.0–19.1%]. The median PFS and OS were 2.14 months (95% CI, 2.09–2.16 months) and 8.87 months (95% CI, 8.65–9.61 months), respectively. In a subset analysis, the PFS of EGFR wild type and unknown status were 1.08 months and 1.48 months, respectively, whereas the PFS of EGFR active mutation was 5.29 months (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Survival curve of each EGFR mutation status. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; PFS, progression free survival.

Analysis of the RR according to the EGFR mutation status

According to the RECIST criteria, the RR of 95 patients with an EGFR mutation was 25% (24/43/28, PR/SD/PD; 95% CI, 15–34%). Conversely, the RR of 52 EGFR wild type and 75 unknown patients were 6% (3/25/24, PR/SD/PD; 95% CI, 1.3–15%) and 5% (4/33/38, PR/SD/PD; 95% CI, 2.1–13%), respectively (Table II).

Table II.

Subset analysis of the EGFR mutation status.

| Response (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR mutation status | Gefitinib treatment status | n=222 | CR | PR | SD | PD | RR | 95% CI (%) |

| Mutated | Total (Prior gefitinib treatment) | 95 | 0 | 24 | 43 | 28 | 25 | 15–34 |

| Yes | 50 | 0 | 7 | 29 | 14 | 14 | 7–26 | |

| No | 45 | 0 | 17 | 14 | 14 | 38 | 25–52 | |

| Wild type | Total (Prior gefitinib treatment) | 52 | 0 | 3 | 25 | 24 | 6 | 1.3–15 |

| Yes | 10 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 | – | |

| No | 42 | 0 | 3 | 17 | 22 | 7 | 2–19 | |

| Unknown | Total (Prior gefitinib treatment) | 75 | 0 | 4 | 33 | 38 | 5 | 2.1–13 |

| Yes | 32 | 0 | 2 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 2–20 | |

| No | 43 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 26 | 5 | 1–15 | |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; RR, response rate; CI, confidence interval.

Univariate and multivariate survival analyses

To rule out potential cofounding interaction between efficacy and other factors, the present study performed univariate and multivariate analyses of the PFS. Kaplan-Meier analyses compared by the log-rank test were used to calculate the effect of the clinicopathological factors on the PFS (Table III). A univariate analysis demonstrated that male gender [hazard ratio (HR) 1.63; P<0.001], poor PS (PS 3 or 4; HR 1.75; P=0.028), current or former smoking history (HR 1.64; P<0.001), prior regimens (2 or more) (HR 1.44; P=0.036) and EGFR wild type or unknown (HR 2.09; P<0.001) status significantly predicted a decreased PFS. Furthermore, a multivariate analysis identified only EGFR mutation (HR 1.89; P<0.001) to be an independent prognostic factor for PFS.

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with the progression-free survival (all patients).

| Variable | No. of patients | Univariate hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Multivariate hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.0009 | 0.164 | |||

| Male | 119 | 1.626 (1.219–2.169) | 1.333 (0.889–2.004) | ||

| Female | 103 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ECOG performance status | 0.0278 | 0.629 | |||

| 3–4 | 20 | 1.754 (1.063–2.894) | 1.635 (0.974–2.746) | ||

| 0–2 | 202 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Smoking history | 0.0009 | 0.534 | |||

| Current or former | 100 | 1.639 (1.225–2.192) | 1.142 (0.752–1.730) | ||

| Never | 122 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Histological type | 0.1370 | ||||

| Non-adenocarcinoma | 31 | 1.371 (0.904–2.079) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 191 | 1 | |||

| Prior gefitinib treatment | 0.3890 | ||||

| No | 131 | 1.135 (0.851–1.515) | |||

| Yes | 91 | 1 | |||

| Prior regimens | 0.0364 | 0.867 | |||

| >2 | 164 | 1.438 (1.023–2.020) | 1.034 (0.701–1.529) | ||

| 0–1 | 58 | 1 | 1 | ||

| EGFR status | <0.0001 | <0.001 | |||

| Wild type or unknown | 170 | 2.087 (1.548–2.814) | 1.892 (1.346–2.662) | ||

| Mutation | 52 | 1 | 1 |

CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

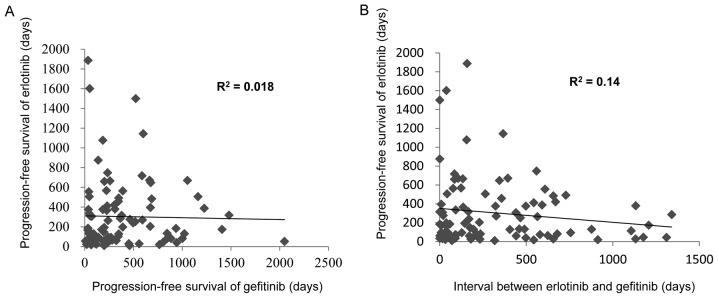

Association between the PFS and prior gefitinib therapy

Of the 222 patients treated with erlotinib, 91 patients previously received gefitinib. To evaluate the potential cofounding interaction between erlotinib and previous gefitinib therapy, the present study performed univariate and multivariate analyses of the PFS (Table III). A univariate analysis demonstrated that non-adenocarcinoma (HR 4.78; P=0.035) and poor response of gefitinib (HR 2.27; P=0.014) significantly predicted a decreased PFS. However, the multivariate analysis identified no association between the characteristics and the PFS of erlotinib. Furthermore, as it was speculated that a response to erlotinib treatment may be associated with a long interval of a previous gefitinib therapy or a long duration from erlotinib to gefitinib therapy, the present study investigated the impact of a long disease control interval on the survival outcome among patients treated with gefitinib who achieved ≥12 months PFS (Table IV). However, no significant correlation was detected between previous gefitinib therapy and the PFS of erlotinib therapy (Fig. 2).

Table IV.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with the progression-free survival (patients who received previous gefitinib treatment).

| Variable | No. of patients | Univariate hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Multivariate hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.235 | ||||

| Male | 24 | 1.342 (0.825–2.183) | |||

| Female | 67 | 1 | |||

| ECOG performance status | 0.587 | ||||

| 3–4 | 9 | 1.226 (0.588–2.556) | |||

| 0–2 | 82 | 1 | |||

| Smoking history | 0.615 | ||||

| Current or former | 31 | 1.123 (0.714–1.766) | |||

| Never | 60 | 1 | |||

| Histological type | 0.035 | 0.809 | |||

| Non-adenocarcinoma | 2 | 4.784 (1.116–20.408) | 3.74 (0.850–16.393) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 89 | 1 | |||

| Prior regimens | 0.125 | ||||

| >2 | 77 | 1.690 (0.864–3.303) | |||

| 0–1 | 14 | 1 | |||

| EGFR status | 0.388 | ||||

| Wild type or unknown | 41 | 1.210 (0.784–1.865) | |||

| Mutation | 50 | 1 | |||

| Response of gefitinib | 0.0139 | 0.249 | |||

| PD | 12 | 2.271 (1.181–4.365) | 2.141 (1.101–4.164) | ||

| CR-SD | 79 | 1 | |||

| Duration of gefitinib treatment | 0.6125 | ||||

| <12 | 58 | 1.122 (0.718–1.754) | |||

| >12 | 33 | 1 | |||

| Interval between gefitinib and erlotinib treatment | 0.429 | ||||

| <12 | 57 | 1.197 (0.766–1.871) | |||

| >12 | 34 | 1 |

CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; PD, progressive disease; CR, complete response; SD, stable disease.

Figure 2.

Correlations were assessed between previous gefitinib therapy and the progression free survival of erlotinib therapy. (A) Correlation between the PFS of erlotinib and the PFS of gefitinib. (B) Correlation between the PFS of erlotinib against the interval from gefitinib to erlotinib. PFS, progression free survival.

Discussion

At present, several EGFR TKIs are commercially available for patients with EGFR mutations: Gefitinib, erlotinib and afatinib (20). Erlotinib, an orally available EGFR TKI, has proven to be effective as a second- or third-line treatment for patients with NSCLC, regardless of the EGFR mutation status (9). Additionally, maintenance therapy with erlotinib for patients with NSCLC is well-tolerated and significantly prolongs the PFS compared with placebo (21). In these trials, subgroup analyses of the PFS according to the clinical characteristics also suggested an improved PFS with erlotinib treatment compared with the placebo; this benefit was observed irrespective of histology and EGFR mutation status. However, erlotinib was compared with BCS or placebo for unselected patients with NSCLC, which included patients with wild type EGFR in the BR.21 and Sequential Tarceva in Unresectable NSCLC trials (9,21).

As the benefit of EGFR TKIs varies widely between patients with EGFR mutations and those with wild type EGFR, it is crucial to establish which second- or third-line treatment is preferable, particularly for patients with wild type EGFR (22). The TAILOR phase III trial, conducted to compare erlotinib with docetaxel in patients who failed first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and who had EGFR wild type, demonstrated that chemotherapy was more effective compared with erlotinib for the second-line treatment for previously treated patients with NSCLC with EGFR wild type (16). Erlotinib had low efficacy for patients with wild type EGFR compared with patients who had EGFR active mutations. In addition, the effectiveness of erlotinib subsequent to gefitinib therapy remains controversial.

The present study analyzed the characteristics of 222 patients according to the response to erlotinib. The multivariate analysis revealed that the EGFR mutation status (with active mutation) was only associated with a longer PFS and good response to erlotinib treatment. Patients with wild type EGFR or unknown status had a poor PFS (1.1 and 1.5 months, respectively) and RR (6 and 5%, respectively). Similarly, the TAILOR phase III trial, which compared erlotinib with standard chemotherapy in patients with wild type EGFR as second-line chemotherapy, demonstrated that the RR of erlotinib in wild type EGFR patients was 3–5.6%, whereas that of standard chemotherapy was 10.3–20% (16). In addition, a randomized phase III trial (Docetaxel and Erlotinib Lung cancer trial) of erlotinib vs. docetaxel in Japanese patients with advanced NSCLC who had an EGFR wild type status demonstrated the poor effectiveness of erlotinib as a second or third-line therapy. The RR of chemotherapy for patients with NSCLC as a second-line therapy was 7.1–22.7% (23–25). The present study therefore considered erlotinib to be invalid for patients with NSCLC with wild type EGFR as a second or third-line therapy.

The current study analyzed the characteristics of 95 patients according to the response and interval time on erlotinib subsequent to gefitinib failure. In these patients, a significantly altered response following erlotinib therapy was observed in patients who had exhibited SD for a long period of time during gefitinib treatment. Thus, it appeared that erlotinib is a potential therapeutic option for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC with wild type EGFR who had SD while receiving gefitinib, as previously suggested (26). However, there was no association between the erlotinib and gefitinib treatments. The predictive factor of erlotinib subsequent to gefitinib therapy was associated with the EGFR mutation status alone.

Although the PFS was markedly improved with EGFR TKI treatment compared with chemotherapy in such EGFR mutated patients, patients who had initially responded to EGFR TKI treatment eventually relapsed (27). This acquired resistance to EGFR TKI treatment may be linked to a number of molecular mechanisms, including secondary mutations in the EGFR gene coding for the intracellular kinase domain of this receptor, a T790M mutation and other factors, including MET amplification and hepatocyte growth factor overexpression (28–30). Thus, oncologists may consider a repeat biopsy prior to retreatment with EGFR TKI subsequent to the initial EGFR TKI failure.

In conclusion, the efficacy of erlotinib therapy was closely associated with the EGFR mutation status. Erlotinib treatment is therefore considered to be limited for patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations, at least as a second or third-line therapy.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potosky AL, Saxman S, Wallace RB, Lynch CF. Population variations in the initial treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3261–3268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramalingam S, Belani C. Systemic chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Recent advances and future directions. Oncologist. 2008;13(Suppl 1):S5–S13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, Palmero R, Garcia-Gomez R, Pallares C, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, Zhu J, Johnson DH, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohe Y, Ohashi Y, Kubota K, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Negoro S, Nishiwaki Y, Saijo N, Ariyoshi Y, Fukuoka M, et al. Randomized phase III study of cisplatin plus irinotecan versus carboplatin plus paclitaxel, cisplatin plus gemcitabine, and cisplatin plus vinorelbine for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Four-Arm Cooperative Study in Japan. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:317–323. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shepherd FA, Pereira J Rodrigues, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, Singh B, Heelan R, Rusch V, Fulton L, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from ‘never smokers’ and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2004; pp. 13306–13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, Gemma A, Harada M, Yoshizawa H, Kinoshita I, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, Seto T, Satouchi M, Tada H, Hirashima T, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ, Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garassino MC, Martelli O, Broggini M, Farina G, Veronese S, Rulli E, Bianchi F, Bettini A, Longo F, Moscetti L, et al. Erlotinib versus docetaxel as second-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and wild-type EGFR tumours (TAILOR): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:981–988. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postmus PE, Brambilla E, Chansky K, Crowley J, Goldstraw P, Patz EF, Jr, Yokomise H. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer International Staging Committee; Cancer Research and Biostatistics; Observers to the Committee; Participating Institutions: The IASLC lung cancer staging project: Proposals for revision of the M descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:686–693. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31811f4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zubrod CG, Ipsen J, Frei E, Lc, Lipsett Mb, Gehan E Lasagna, Escher Gc. Newer techniques and some problems in cooperative group studies. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1960;3:277–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CK, Brown C, Gralla RJ, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Tsai CM, Tan EH, Ho JC, Chu da T, Zaatar A, et al. Impact of EGFR inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer on progression-free and overall survival: A meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:595–605. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, Szczésna A, Juhász E, Esteban E, Molinier O, Brugger W, Melezínek I, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laurie SA, Goss GD. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in epidermal growth factor receptor wild-type non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1061–1069. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M, Levitan N, Gressot L, Vincent M, Burkes R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, Crawford J, Natale RR, Dunphy F, Kalman L, Miller V, Lee JS, Moore M, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 non-small cell lung cancer study group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2354–2362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kudoh S, Takeda K, Nakagawa K, Takada M, Katakami N, Matsui K, Shinkai T, Sawa T, Goto I, Semba H, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel compared with vinorelbine in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group Trial (WJTOG 9904) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3657–3663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho BC, Im CK, Park MS, Kim SK, Chang J, Park JP, Choi HJ, Kim YJ, Shin SJ, Sohn JH, et al. Phase II study of erlotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2528–2533. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remon J, Morán T, Majem M, Reguart N, Dalmau E, Márquez-Medina D, Lianes P. Acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: A new era begins. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, Woo MS, Greulich H, Wong KK, Meyerson M, Eck MJ. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2008; pp. 2070–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bean J, Brennan C, Shih JY, Riely G, Viale A, Wang L, Chitale D, Motoi N, Szoke J, Broderick S, et al. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2007; pp. 20932–20937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yano S, Wang W, Li Q, Matsumoto K, Sakurama H, Nakamura T, Ogino H, Kakiuchi S, Hanibuchi M, Nishioka Y, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces gefitinib resistance of lung adenocarcinoma with epidermal growth factor receptor-activating mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9479–9487. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]