Abstract

Objective

To analyze successful national smokefree policy implementation in Colombia, a middle income country.

Materials and methods

Key informants at the national and local levels were interviewed and news sources and government ministry resolutions were reviewed.

Results

Colombia’s Ministry of Health coordinated local implementation practices, which were strongest in larger cities with supportive leadership. Nongovernmental organizations provided technical assistance and highlighted noncompliance. Organizations outside Colombia funded some of these efforts. The bar owners’ association provided concerted education campaigns. Tobacco interests did not openly challenge implementation.

Conclusions

Health organization monitoring, external funding, and hospitality industry support contributed to effective implementation, and could be cultivated in other low and middle income countries.

Keywords: tobacco, tobacco industry, public policy, Latin America, Colombia

Smokefree laws protect nonsmokers from secondhand smoke and reduce tobacco-induced diseases.1 The 2005 World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control’s2 (FCTC) Article 8 commits parties to implementing smokefree laws.3

The experience of high income countries4–10 shows that successful implementation requires active education and enforcement,9,11 appropriate enforcement agencies,5 and support from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).4 Tobacco companies encourage noncompliance directly and through third parties,4,11 lobbying,6,9,10,12 litigating,7 and thwarting the implementation of rules.8,13

Smoke-free implementation for low and middle-income countries (LMICs) is challenging because tobacco companies often have more resources than the health authorities,14 and tobacco industry activities are less controlled,12 making implementation weak or uneven.15–17

Colombia, with an adult smoking prevalence of 12.8% in 2007,18 low for Latin America, adopted national smokefree policies before many LMICs.19 In May 2008, the Health Ministry issued Resolución 1956 de 2008 (Ministerial Resolution No. 1956), mandating smokefree indoor public areas. In July 2009, Ley 1335 de 2009, a comprehensive tobacco control law, expanded smokefree coverage to all hospitality venues,20 making Colombia the country with lowest gross domestic product per capita with such a national smokefree law.21

Successful implementation of Colombia’s 2008 resolution and 2009 law involved national and local health department efforts, with technical and financial help from domestic and international health NGOs.

Material and methods

From July 2014 to July 2015, we reviewed Colombian government ministries’ resolutions, administrative orders, government agency webpages, and public documents related to Colombia’s 2008 smokefree resolution and 2009 tobacco control law, articles of daily newspapers with national reach dated between January 2008 and July 2015, and related legislation, court rulings, and local government resolutions, using standard snowball methods.

We conducted interviews with 14 in-country tobacco control advocates, national and local health authorities, and policymakers between October 2014 and December 2014 following protocol IRB #10–01262 approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research (table I).22 Informed consent was obtained in accordance with ethical principles of medical research involving human subjects of the Helsinki Declaration.

Table I.

Key Actors Influencing Implementation and Interviewed Actors. Colombia, 2008–2016

| Actor | Description | Implementation activities |

|---|---|---|

| National government bodies | ||

| Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social (hereafter, “Health Ministry”)* | National health ministry, with current name since 2011 emphasizing health issues‡ | Pursued high-level efforts since health matters are decentralized in Colombia;§ diffused and encouraged local implementation practices |

|

| ||

| Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (National Cancer Institute)* | Unit of the Health Ministry | Technical assistance, monitoring |

|

| ||

| Procuraduría General de la Nación (National Inspector General)‡ | Ensures government bodies’ compliance with Colombian law. | Focused largely on conflict-related human rights‡ |

| Local government bodies | ||

| Local health departments* | For local governments including Colombia’s 32 departamentos (departments) and major cities; have wide autonomy | Education and enforcement |

|

| ||

| Local police | Enforcement | |

| Health and other nongovernmental organizations | ||

| Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer (Colombian League Against Cancer)* | Health nongovernmental organization | Education and highlighting noncompliance |

|

| ||

| Corporate Accountability International* | Watchdog organization; Latin America branch headquartered in Colombia | Monitoring and highlighting noncompliance |

|

| ||

| Fundación para la Educación y el Desarollo Social FES* | Social equity organization | Training local health department staff |

|

| ||

| Asociación de Bares de Colombia (Asobares; Bar Owners’ Association of Colombia)* | Bar owners’ national trade organization | Education |

| Tobacco companies and third-party allies | ||

| Compañía Colombiana de Tabaco ( Colombian Tobacco Company, Coltabaco) | Purchased by Philip Morris in 2005; Coltabaco and Protabaco controlled over 90% of the market22 | Opposed adoption#,& but did not openly oppose implementation |

|

| ||

| Productora Colombiana de Tabaco (Colombian Tobacco Producer, Protabaco) | Purchased by British American Tobacco in 2011 | Opposed adoption& but did not openly oppose implementation |

|

| ||

| Federación Nacional de Comerciantes (Fenalco) | National Merchants’ Federation | Argued for smokefree laws to exclude uncovered terraces |

Agency reached as part of key informant interviews

Calderón L. Interview of Lorena Calderón, tobacco program manager at the Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014

Hernández B. Interview of Blanca Hernández, former tobacco program manager at Ministerio de la Protección Social no longer working on tobacco, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014

Ronderos M. Interview of Margarita Ronderos, professor at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014

Rivera Rodríguez DE. Interview of Diana Esperanza Rivera Rodríguez, former public policy director, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014

Results

Early attempts at smokefree legislation

Colombia’s 2008 smokefree resolution and 2009 law were adopted after decades of failed attempts23,24 that were blocked by tobacco industry interests, tobacco-growing area legislators,* and the Ministry of Agriculture,* despite tobacco being less than 0.1% of Colombia’s exports.25 In 2006, Sen. Dilian Francisca Toro, a physician allied with President Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010),26 became Senate President and pushed for Colombia to join the FCTC,27 which it did in April 2008. Health advocates then argued for legislation to comply with the FCTC.*

Colombia’s 2008 smokefree resolution and 2009 law

Resolución 1956 de 2008, issued in May 2008 by the Health Ministry28 (then called the Ministry of Social Protection), mandated smokefree indoor public areas nationwide.

Ley 1335 de 2009 (“Law 1335 of 2009”), sponsored by Sen. Toro, passed in July 2009 to implement FCTC Articles 8 and 10–16 including smokefree areas, prohibiting tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, and prohibiting individual cigarette sales.* The law went beyond Resolución 1956 de 2008 (table II),29 by requiring smokefree grounds of educational institutions, cultural institutions such as museums, and health facilities. The Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (National Cancer Institute, part of the Health Ministry), Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer (Colombian League Against Cancer), the Colombia-based Latin America branch of Corporate Accountability International, and Sociedad Colombiana de Cardiología (Colombian Society of Cardiology) supported its passage;23,30,31 representatives friendly to the tobacco industry opposed it.23 Philip Morris, British American Tobacco, and local tobacco company Protabaco tried unsuccessfully to permit designated smoking areas.23

Table II.

Smokefree Policies in Colombia, 2008–2009

| Provisions | Resolución 1956 de 200828 | Ley 1335 de 200920 |

|---|---|---|

| Indoor smokefree | Indoor workplaces Indoor publicly accessible places |

Enclosed areas of workplaces and public places (including bars, restaurants, pubs, casinos, nightclubs) |

| Entirety smokefree, including outdoors | Health establishments Preschool, primary, middle schools Places for people under 18 Public and school transport |

Health establishments Education/museums/libraries Sports/cultural spaces Places for youth Places for industrial activity transportation for the public (including taxis) |

| Effective date | December 4, 2008 | July 21, 2009 |

| Signage | Required one of three positive messages, without cigarette brand names or figures alluding to cigarettes | Required, without specific message text |

| Fines | In accordance with existing laws | Starting at 1 monthly minimum wage (in 2009 was 496 900 Colombian pesos29 or about 250 dollars) or suspension of health license |

| Implementing actors specified in law | Ministry of Health Local health authorities Governors and mayors |

Ministry of Health, local health authorities in coordination with police and other authorities |

| Additional implementing actors | Nongovernmental health organizations Bar owners’ association |

Nongovernmental health organizations, bar owners’ association, universities |

Implementation of the smokefree provisions did not face the concerted tobacco industry opposition common elsewhere,4, 6, 9–13, 16, 32 likely because the companies seem to have focused on countering the prohibitions on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship.

Processes and results in implementation

The Health Ministry, local health authorities, local police, NGOs, the national barowners’ association (Asobares), and individual establishments, including universities, contributed to implementation. Implementation, with generally good compliance and enforcement, varied regionally. As in high income countries,33–35 implementation included guidance from the Health Ministry to local health departments, education by health departments and advocates, and enforcement by local health authorities and police, especially in major cities. In 2015, a survey in large cities found that 92% of nonsmokers and 91% of smokers supported the 2009 law.36

National-local dynamics

Colombia’s low state capacity37 meant limited national agency efforts. Health policy implementation was decentralized across local health agencies for Colombia’s major cities, 32 departamentos (departments), and capital district. The Health Ministry provided guidance, but local agencies had autonomy* in educational efforts, and worked with local police on enforcement.

National government activities

To implement the 2008 resolution, in December 2008 the Health Ministry distributed a “circular”,38 i.e. a memo to local health departments, detailing that it expected local public education and enforcement activities, without requiring specific activities.

For the 2009 law, the Health Ministry shared surveillance, education, and enforcement practices among local health departments.* Bogotá included smokefree surveillance in routine health inspections,* resulting in 162,000 inspections in 2009 and 197,000 by 2011,39 with compliance in a low-income Bogotá neighborhood estimated at 91%.40 The Instituto Nacional de Cancerología provided technical assistance to the Health Ministry, including monitoring.‡ Limited Health Ministry resources for tobacco control,§ however, meant the absence of a strong national smokefree education campaign.41

The Procuraduría General de la Nación (National Inspector General), constitutionally responsible for ensuring compliance with laws by government agencies, did not focus on compelling local smokefree education and enforcement because it was focused on Colombia’s internal armed conflict and conflict-related human rights.42 The Health Ministry asked the Procuraduría to focus more on local health agency smokefree education and enforcement, and the Procuraduría issued a “circular” memo43 requesting local health departments to implement the law, but did little follow-up, which resulted in variations in activity.

Local government bodies’ activities: Regional variation

Implementation was strongest in big cities and in cities with supportive political leadership: Bogotá (population 8 million), Medellín (2.4 million), Cali (2.3 million), Colombia’s most influential cities, and two southwestern cities, Popayán (250000) and Pasto (480000), with personally committed mayors. Local health departments distributed materials to business owners and the public before and after implementation.

Implementation was weakest in rural areas and the Atlantic coast, with less interest from agencies in these areas.* Health advocates had focused on large cities,* and the Colombian state had more presence in departmental capitals. Rural and small-city health agencies often knew little of the law* or claimed having limited resources and personnel.44

Supportive political leadership in Popayán and Pasto resulted in the reiteration of the local health departments’ implementation responsibilities‡,§ and in crafting educational efforts annually§,‡ for restaurant, bar, and nightclub owners,*,‡ by the mayors’ offices. Popayán also conducted smokefree education at schools.*,‡

Local police: Attention to public security

Consistent with FCTC guidelines,3 the 2009 law authorized enforcement by local police and health authorities. Given Colombia’s armed conflict, many police departments did not prioritize smokefree enforcement; however, Bogotá, Medellín, and Pasto’s health departments convinced local police to carry out enforcement.#

Signage requirements

The 2008 resolution required establishments to post signs with specified smokefree messages (“For the good of your health, this space is free of cigarette or tobacco smoke,” “Breathe easy, this space is free of tobacco smoke,” “Welcome, this establishment is free of tobacco smoke”). The resolution prohibited cigarette brand logos and images “alluding to cigarettes” so the signs did not carry the international “no smoking” symbol. Establishments could post signs referring to smokefree environments (a positive message) without any “no smoking” symbol (a negative message), then optionally could post additional signs carrying the symbol. The 2009 law required signage about smokefree environments, but without a predefined list, allowing for more expansive text (figure 1). Since “no smoking” signs may prime smoking tendencies,45 Colombia’s positive smokefree messaging may have improved compliance.

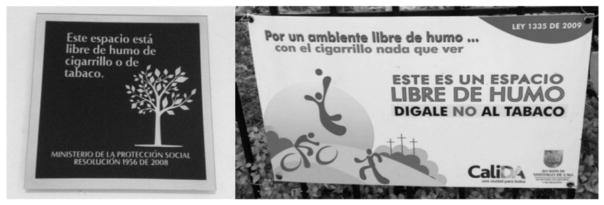

Figure 1.

Examples of smokefree signs posted following the 2008 smokefree resolution, with a specific message mandated by the resolution (on left, “This space is free of cigarette or tobacco smoke”) and a smokefree sign citing the 2009 tobacco control law, with more expansive text (on right, “This is a smokefree space; say no to tobacco”)

Outside funders: Supporting NGO activities

Organizations outside Colombia funded Colombian NGOs to create educational materials and train local health department staff. As elsewhere in Latin America, the US-based Bloomberg Foundation’s Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use funded Colombian NGOs for smokefree education, training, and monitoring, totaling 501563 dollars through October 2015.46 Corporate Accountability International’s Colombia-based staff highlighted noncompliance starting in 2008 and provided technical assistance to defend the 2009 law against potential industry litigation.* The Bogotá-based Universidad Sergio Arboleda improved community involvement in 2010–2012, the Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer (Colombian League Against Cancer) conducted smokefree education in 2012,* and the health and civic group Fundación FES trained local health departments in 2014.‡

In particular, the Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer and Corporate Accountability International joined Senator Toro in 2011 to highlight noncompliance to the Ministry of Health and news media.42 Since health advocates in the 2000s had sensitized journalists to tobacco control,§ coverage often called for national and local efforts.

Advocates also worked with the Bogotá-based Universidad Sergio Arboleda to create “Opción No Fumar” (the Non-smoking Option) campaign, distributing flyers, postcards, and pamphlets about the law.* By July 2013, “Opción No Fumar” had distributed 29 350 pamphlets.47

Controversy about terraces: The merchants’ federation Fenalco and NGO vigilance

The Federación Nacional de Comerciantes (Colombian Merchants’ Federation, Fenalco) interpreted the 2009 law’s smokefree provisions as not applying to terrace areas of restaurants and bars. Fenalco had cooperated in the past with tobacco industry “youth smoking prevention” programs48 designed to displace government action.49

In 2010 and 2011 Fenalco distributed flyers to business owners and employees claiming smoking in terraces was allowed44,50 because they were not under roofs51 and claimed that health advocates were maligning Fenalco for its interpretation.51 Despite the support of the Health Ministry and NGOs,44,50 whether implementation included terraces depended on local health authorities. Medellín only enforced covered terraces,52 while in 2011 Bogotá’s health department declared it would enforce all terraces.53

Strong support from the Bar Owners’ Association (Asobares)

The Asociación de Bares de Colombia (Asobares, Association of Bars of Colombia) supported implementation strongly but initially had opposed the 2008 resolution,* reflecting the efforts of the tobacco industry to turn hospitality groups against smokefree laws.4,6 Some of Asobares’ executive committee were personally affected by secondhand smoke, so Asobares surveyed its members and found that a majority supported the resolution, so shifted to supporting it.* The tobacco industry did not appear to interfere with this change.

Asobares conducted intensive education for bar owners for six months before the 2008 resolution’s December 4 effective date,* including brochures, and bar coasters co-sponsored by the Health Department of Bogotá, Bogotá Mayor’s Office, and World Heart Federation, reading: “Si va a fumar, hágalo afuera” (“If you are going to smoke, do it outside”).* Asobares provided candy to people who stepped outside to smoke, had models come to bars to give prizes to such people, and worked with the Bogotá government on a protocol for the emergency services number (123), which would summon police to eject patrons who insisted on smoking indoors.* These activities set a tone of compliance from the start.

University activities: Smokefree outdoors

Universities developed educational campaigns to implement smokefree educational institutions. In Bogotá, 21 universities cooperated to develop similar campaigns, and in Cali, 13 universities joined a local health department network to share information on campaigns.54,55 The Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá and Cali, with personal interest from the Bogotá campus rector,‡ had the Bogotá campus establish signs at campus entrances and major outdoor locations, including a life-size sign of a student announcing a smokefree campus. The Cali campus put signs throughout, including person-high signs saying, “En la universidad no se fuma” (“At the university, there is no smoking”).56

Discussion

Like high income countries,4,11,57 Colombia’s successful smokefree implementation required sustained engagement by national and local health authorities, NGO, external funders, the national bar owners’ association, and universities. Different from high income countries, in Colombia there were few government resources, weak state capacity, and enforcement agencies focused on public security.

Like many Latin American countries, Colombia lacked a strong national smokefree education campaign,16 but had many vigorous local campaigns.45 Colombia benefited from national and local agencies and support from legislative champions, and notably has a successful history of public health policies.58,59

Three factors in Colombia especially contributed to strong implementation. First, noncompliance vigilantly exposed by NGOs, including for terraces, as in the case of local implementation in Mexico and the US.4,13 The merchants’ federation argued against applying the law to terraces, creating an ambiguity about patio-like areas that also occurred in the US.6,9–11,60

Second, support by the Bar Owners’ Association set a tone of compliance similar to that of California in the US,61 showing how organizations within the society, not just government agencies, are essential to compliance. Since 2008, Asobares, with the help from the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, visited hospitality associations throughout Latin America to encourage national smokefree laws.*

Third, international organizations aided implementation, supporting NGOs to provide education and technical assistance.62 Sustained resources are necessities for long term compliance,63 and external funding often does not last, so international organizations’ support provides a crucial opportunity to help LMIC smokefree implementation.

These factors contributed to robust implementation despite Colombia’s health policy decentralization, weak state capacity, and public security issues.

Policy implications

Smokefree legislation should clearly cover all workplaces and specify national and local agency responsibilities. Health advocates should cultivate hospitality association support in advance of legislation, when possible. International funders should continue strongly funding LMIC implementation, as moderate resources can make substantial impacts.

Limitations

We attempted to contact tobacco control staff in departmental and large-city health agencies throughout Colombia. Only those highly engaged in implementation agreed to interviews, so our findings hold to the extent that such interviews captured the key issues of local implementation.

Conclusions

Colombia serves as an example of successful implementation of smokefree air in a middle income country. Beyond government agency activities, health organization vigilance, outside organization funding, and hospitality industry support contributed to strong implementation.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by National Cancer Institute grant CA-087472 and UCSF funds from the FAMRI William Cahan Endowment Fund and Dr. Glantz’ American Legacy Foundation Distinguished Professorship. The funding agencies played no role in the selection of the research question, conduct of the research, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Toro Torres DF. Interview of Dilian Francisca Toro Torres, former Colombian senator and former President of the Senate of Colombia, by Randy Uang. Cali, Colombia. 2014.

Hernández B. Interview of Blanca Hernández, former tobacco program manager at Ministerio de la Protección Social no longer working on tobacco, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Niño-Bogoya A. Interview of Alejandro Niño Bogoya, public policy director at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Calderón L. Interview of Lorena Calderón, tobacco program manager at the Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Dorado YF. Interview of Yul Francisco Dorado, regional director at Corporate Accountability International, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Dorado YF. Interview of Yul Francisco Dorado, regional director at Corporate Accountability International, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Lagos Campos N. Telephone interview of Nancy Lagos Campos, coordinator of the chronic diseases program at the Secretaría de Salud de Pasto, by Randy Uang. 2014.

Ramos Quilindo, interview.

Hernández B, interview.

Dorado YF. Interview of Yul Francisco Dorado, Regional Director at Corporate Accountability International, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Barón E, Llorente B. Interview of Edwin Barón, director of education at Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer, and Blanca Llorente, technical advisor at Fundación Anáas, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Varela A. Interview of Alejandro Varela, executive director of Fundación FES, by Randy Uang, Cali, Colombia. 2014.

Rivera Rodríguez DE. Interview of Diana Esperanza Rivera Rodríguez, former public policy director, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Ospina C. Interview of Camilo Ospina, executive director of Asociación de Bares de Colombia (Asobares), by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Ronderos M. Interview of Margarita Ronderos, Professor at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Ospina C. Interview of Camilo Ospina, executive director of Asociación de Bares de Colombia (Asobares), by Randy Uang, Bogotá, Colombia. 2014.

Declaration of conflict of interests. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Smokefree and Tobacco-Free Legislation” in the Health Consequences of Smoking--50 Years of Progress. Atlanta, GA: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Guidelines on Protection from Exposure to Tobacco Smoke. Geneva, Switzerland: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.who.int/entity/fctc/cop/art%208%20guidelines_english.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magzamen S, Glantz SA. The New Battleground: California’s Experience with Smoke-Free Bars. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:245–252. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.245. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.2.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamudu HM, Dadkar S, Veeranki SP, He Y. [accessed on February 2016];Tobacco Control in Tennessee: Stakeholder Analysis of the Development of the 2007 Non-Smoker Protection Act. Available at: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/8z38c04x.

- 6.Dearlove JV, Bialous SA, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Manipulation of the Hospitality Industry to Maintain Smoking in Public Places. Tob Control. 2002;11:94–104. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.94. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.11.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim JK, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Litigation Strategies to Oppose Tobacco Control Media Campaigns. Tob Control. 2006;15:50–58. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014142. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2005.014142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson G, Wilson N. Implementation Failures in the Use of Two New Zealand Laws to Control the Tobacco Industry: 1989–2005. Australia and New Zealand Health Policy. 2005;2:32. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-2-32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8462-2-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drope J, Glantz S. British Columbia Capital Regional District 100% Smokefree Bylaw: A Successful Public Health Campaign Despite Industry Opposition. Tob Control. 2003;12:264–268. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.3.264. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsoukalas T, Glantz SA. The Duluth Clean Indoor Air Ordinance: Problems and Success in Fighting the Tobacco Industry at the Local Level in the 21st Century. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1214–1221. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1214. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez M, Glantz SA. Failure of Policy Regarding Smoke-Free Bars in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:139–145. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr173. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckr173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The Vector of the Tobacco Epidemic: Tobacco Industry Practices in Low and Middle-Income Countries. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(Suppl 1):117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosbie E, Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Strong Advocacy Led to Successful Implementation of Smokefree Mexico City. Tob Control. 2011;20:64–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037010. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2010.037010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sebrie E. The Tobacco Industry in Developing Countries. BMJ. 2006;332:313–314. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7537.313. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7537.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drope J, editor. Tobacco Control in Africa: People, Politics and Policies. London, England: Anthem Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith G, Cardone A, Jo C, Valdemoro A, Sebrie E. Implementation of Smoke Free Workplaces: Challenges in Latin America. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Suppl 2):S347–S354. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0036-36342010000800033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur J, Jain DC. Tobacco Control Policies in India: Implementation and Challenges. Indian Journal of Public Health. 2011;55:220–227. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89941. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-557X.89941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Socialización del informe final de evaluación de necesidades para la ampliación del convenio marco de control del tabaco. Bogota, Colombia: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.minsalud.gov.co/Documents/General/Cifras-tabaco-Colombia.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Who Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013: Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship. Geneva, Switzerland: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85380/1/9789241505871_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.República de Colombia. Ley No. 1335. Bogota, Colombia: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Colombia/Colombia%20-%20Law%20No.%201335%20-%20national.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Bank. [accessed on February 2016];GDP Per Capita (Current US$) Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.

- 22.Pan American Health Organization. Scientific Publication No. 536. Washington, D.C: [accessed on February 2016]. Tobacco or Health: Status in the Americas. Available at: http://ceca.barganibar.net/can-i/tobacco-or-health-status-in-the-americas-a-report-of-the-pan-american-health-organization-paho-scientific-publications-no-536.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marín L. Aún quedan muchos cigarrillos por apagar de aprobar la ley antitabaco. Bogotá: La Silla Vacía; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Ruiz MA, Rivera-Rodríguez DE, Marín Y, Gonzalez JC, Murillo Moreno RH. Las Iniciativas para el control del tabaco en el Congreso de Colombia: 1992–2007. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;25:471–480. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892009000600002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Observatory of Economic Complexity. Products Exported by Colombia. Massachussetts, United States: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2012. [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/explore/tree_map/hs/export/col/all/show/2012/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montero D. Dilian Francisca Toro, La Baronesa de la Salud. Bogotá: La Silla Vacia; Nov, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.República de Colombia. Ley No. 1109. Bogota, Colombia: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=22663. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministerio de la Protección Social. Resolución 1956. Bogotá, Colombia: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=30565. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banco de la República. [accessed on February 2016];Salario Mínimo legal en Colombia - Serie Histórica En Pesos Colombianos. Available at: http://obiee.banrep.gov.co/analytics/

- 30.World Heart Federation. Tobacco Control in Colombia: Victory for Heart Health. Geneva, Switzerland: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.world-heart-federation.org/publications/heart-beat-e-newsletter/heart-beat-februarymarchapril-2010/in-this-issue/tobacco-control-in-colombia/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radio Caracol. Caracol Radio. Bogotá, Colombia: Jun, 2009. Aprobación de Ley Antitabaco pone en ‘Jaque’ el futuro de la publicidad de cigarrillos en Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sebrié EM, Glantz SA. Local Smoke-Free Policy Development in Santa Fe, Argentina. Tob Control. 2010;19:110–116. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.030197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lum K, Glantz SA. The Cost of Caution: Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Policy Making in Oregon (1997–2007) San Francisco, United States: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/1nb5k688. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tung G, Glantz SA. Swimming Upstream: Tobacco Policy Making in Nevada. San Francisco, United States: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/4fn8v32x. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendlin YH, Barnes RL, Glantz SA. Tobacco Control in Transition: Public Support and Governmental Disarray in Arizona (1997–2007) San Francisco, United States: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/1nb5k688. [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Tiempo . Fumadores y no fumadores aprueban normas antitabaco. Bogotá, Colombia: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.eltiempo.com/estilo-de-vida/salud/ley-antitabaco-en-colombia-encuesta-muestra-apoyo-a-medidas-para-controlar-el-cigarrillo/16419951. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall MG, Cole BR. Global Report 2014: Conflict, Governance, and State Fragility. Center for Systemic Peace; [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.systemicpeace.org/vlibrary/GlobalReport2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ministerio de la Protección Social. [accessed on February 2016];Circular Externa 80. Available at: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=34201.

- 39.Secretaría Distrital de Salud de Bogotá D.C. Vigilancia Sanitaria y Ambiental: 2006-2011. Bogotá, Colombia: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: www.saludcapital.gov.co/DSP/Anuario%20Vigilancia%20Sanitaria%20y%20Ambiental/Vigilancia%20Ambiental%20y%20Sanitaria%202006-2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hospital Vista Hermosa. Boletín Epidemiológico y Ambiental. Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá D.C: Noviembre. 2014. [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.hospitalvistahermosa.gov.co/web/node/sites/default/files/boletines_2014/BOLETINES_EPIDEMIOLOGICOS/EL_BOLETIN_HVH_NOVIEMBRE%202014_FINALSDS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inter-American Heart Foundation. Civil Society Report. Dallas, Tx: Inter-American Health Foundation; 2010. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Challenges for Latin America and the Caribbean. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergquist C, Peñaranda R, Sánchez G. Violence in Colombia 1990–2000: Waging War and Negotiating Peace. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Procuraduría General de la Nación. [accessed on February 2016];Circular. :31. Available at: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=41944#0.

- 44.González LE. Denuncian incumplimiento de gobierno en ejecución de ley antitabaco. El Tiempo: Mar 22, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Earp BD, Dill B, Harris JL, Ackerman JM, Bargh JA. No sign of quitting: incidental exposure to “no smoking” signs ironically boosts cigarette-approach tendencies in smokers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2013;43:2158–2162. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12202. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloomberg Foundation. [accessed on February 2016];Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use Grants Program. 2015 Available at: http://www.tobaccocontrolgrants.org/Pages/40/What-we-fund?who_region=PAHO&country_id=&amount=&date_type=&date_from=&date_to=&submit=Search.

- 47.Fernández P. [accessed on February 2016];Informe Junta Directiva Campañas: Liga Colombiana Contra el Cáncer. Available at: https://prezi.com/ozaj-fy6-ns-/untitled-prezi/

- 48.Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Attempts to Undermine Tobacco Control: Tobacco Industry “Youth Smoking Prevention” Programs to Undermine Meaningful Tobacco Control in Latin America. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1357–1367. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094128. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.094128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landman A, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry youth smoking prevention programs: protecting the industry and hurting tobacco control. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:917–930. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.917. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El Tiempo. Controversia por terrazas para los fumadores. Aug 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Federación Nacional de Comerciantes. [accessed on February 2016];Las Brujas De Salem. Available at: http://www.fenalco.com.co/contenido/1421.

- 52.El Espectador. ¿Cómo Va La Ley De Espacios Libre De Humo? El Espectador; Bogotá, Colombia: Apr 14, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 53.El Tiempo. ‘Sí está prohibido fumar en terrazas’: Secretario Distrital de Salud. El Tiempo; Apr 12, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Corporación Unificada Nacional de Educación Superior. [accessed on February 2016];Se firmó el pacto por las universidades 100% Libres De Humo. Available at: www.cun.edu.co/dmdocuments/boletin-de-prensa-pacto-univesidades-libres-de-humo.pdf.

- 55.Alcaldía de Cali. [accessed on February 2016];Universidades libres de humo se abren campo en Cali. Available at: http://www.cali.gov.co/publicaciones/universidades_libres_de_humo_se_abren_campo_en_cali_pub.

- 56.Pontificia Universidad Javeriana - Cali. Javerianos respiremos, estrategia desarrollada en la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana – Cali, Ley 1335 de 2009 en el contexto de las Universidades. Cali, Colombia: Programa Universidad Saludable, Centro de Bienestar; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization. Protection from Exposure to Second-Hand Tobacco Smoke: Policy Recommendations. Geneva, Switzerland: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: www.who.int/tobacco/resources/publications/wntd/2007/PR_on_SHS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 58.República de Colombia. Ley No. 670. Bogota, Colombia: [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=4160. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glassman A. From Few to Many: Ten Years of Health Insurance Expansion in Colombia. Washington D.C., United States: Brookings Institution Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uang R, Barnes R, Glantz S. Tobacco Policymaking in Illinois, 1965–2014: Gaining Ground in a Short Time. San Francisco: University of California Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2014. [accessed on February 2016]. Available at: www.escholarship.org/uc/item/6805h95r. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glantz SA, Balbach ED. Tobacco War: Inside the California Battles. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reimann KD. A View from the Top: International Politics, Norms and the Worldwide Growth of NGOs. International Studies Quarterly. 2006;50:45–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00392.x. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Champagne BM, Sebrie E, Schoj V. The role of organized civil society in tobacco control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Suppl 2):S330–S339. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800031. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0036-36342010000800031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]