Abstract

A 41-year-old African male presented with worsening dyspnea and cachexia concerning for congestive heart failure. Transesophageal echocardiogram revealed a large mass attached to the aortic valve leaflet, mass attached to the flail anterior mitral valve leaflet, severe pulmonary hypertension and dilatation of the aortic root along with fistula between the right coronary aortic cusp and the right ventricular (RV) outflow tract. Blood cultures grew Abiotrophia Defectiva (AD) sensitive to vancomycin. Patient underwent emergent surgical closure of aorto RV fistula and aortic root replacement along with pulmonary and mitral valve replacement. Endocarditis caused by AD has been reported to result in heart failure, septic embolization and destruction of the valve despite use of appropriate antibiotics. To our knowledge, this is the only case of AD endocarditis without any identified entrance route; requiring replacement of pulmonary, mitral and aortic valve due to extensive valvular damage and large vegetations.

INTRODUCTION

Abiotrophia species, previously known as nutritionally deficient streptococcus (NDS) was first identified in 1961 by Frenkle and Hirsh in a case of sub-acute infective endocarditis (IE) [1]. NDS was initially classified as Streptococcus Defectiva and Streptococcus Adjacens and later their names were changed to Abiotrophia Defectiva (AD) and Abiotrophia Adjacens. AD is gram-positive cocci, although coccobacilli and bacilli forms may occur, depending on the culture medium.

AD is a part of the normal flora of oral cavity, urogenital and intestinal tracts [2]. It has been associated with a variety of serious infections including bacteremia, septic arthritis, brain abscess and IE, pancreatic abscess, osteomyelitis and crystalline keratopathy [2]. AD affects diseased valves in 90% of cases and it is notorious for embolic complications and valvular destructions despite being sensitive to antibiotics [3]. Previous studies have shown a relapse rate of as high as 17%, despite antibiotic use [3, 4]. We report a rare case of Aorto- Right ventricular (RV) fistula and multiple valve endocarditis caused by AD.

CASE REPORT

A 41-year-old male originally from West Africa with a questionable history of ventriculoseptal defect (VSD), presented with worsening exertional dyspnea and palpitations, loss of appetite, lower extremity edema and a 30 pounds weight loss over 6 weeks. On admission, his temperature was 98.8°F (37.1°C), blood pressure of 104/50 mm Hg, heart rate of 120/min, respiratory rate of 18/min and an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. His physical examination was significant for chronically ill cachexic male with a BMI of 21 kg/m2, jugular venous distension, bilateral rales, tachycardia, RV heave and 4/6 pan-systolic murmur with a palpable thrill throughout the precordium. Blood cultures were obtained for suspected endocarditis and empiric intravenous antibiotics were started. An initial transthoracic echocardiogram and subsequent transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrated a large mass attached to the aortic valve leaflet measuring 3.2 × 0.6 cm (Supplementary Videos 1–2), severe aortic regurgitation with holodiastolic flow reversal in the aorta (Fig. 1), mass attached to the flail anterior mitral valve leaflet resulting in severe mitral regurgitation (Figs 2–5, 8–12, Supplementary Videos 4–7), mass attached to pulmonic valve, significant pulmonic regurgitation (Figs 6, 7, 15) and severe pulmonary hypertension with Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure of 65 mm Hg. Additionally, dilatation of the aortic root along with fistula between the aortic sinus and the RV outflow tract was seen (Figs 7, 13, 14, 16, Supplementary Video 3). Within 24 h, blood culture revealed gram-positive cocci in two out of two bottles, subsequently identified as Abiotrophia species. Patient was transferred to a tertiary care center for further management. He underwent right heart catheterization demonstrating elevated filling pressures, low cardiac index and shunt fraction of 2.1. Emergent surgery revealed an aortic root abscess. He underwent prophylactic grafting of the left anterior descending coronary artery and obtuse marginal artery as the left main coronary Os was close to the aortic annulus. Patient also underwent bio-prosthetic pulmonary and mitral valve replacement, closure of the congenital VSD and closure of aorto-RV fistula using bovine pericardial patches in addition to an aortic root replacement with porcine root prosthesis. Post-operatively, patient developed atrial fibrillation and was subsequently started on amiodarone therapy. He was on intravenous penicillin and gentamycin during his hospitalization. Transesophageal echocardiogram, post intervention, revealed mild left ventricular dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 45% and competent bio-prosthetic valves. Repeat blood cultures remained negative and patient was discharged on intravenous vancomycin via peripherally inserted central catheter.

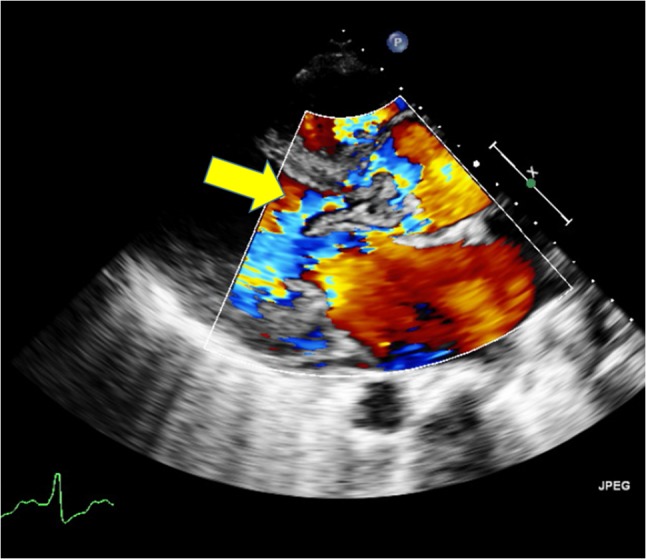

Figure 1:

Holodiastolic flow reversal in aorta.

Figure 2:

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing vegetations attached to mitral and aortic valves.

Figure 5:

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing severe aortic valve regurgitation.

Figure 8:

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing large vegetation attached to mitral valve.

Figure 12:

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing severe mitral valve regurgitation.

Figure 6:

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing vegetations attached to pulmonic and aortic valves

Figure 7:

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing severe pulmonic valve regurgitation and fistula between aortic sinus and the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT).

Figure 15:

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing severe pulmonic valve regurgitation.

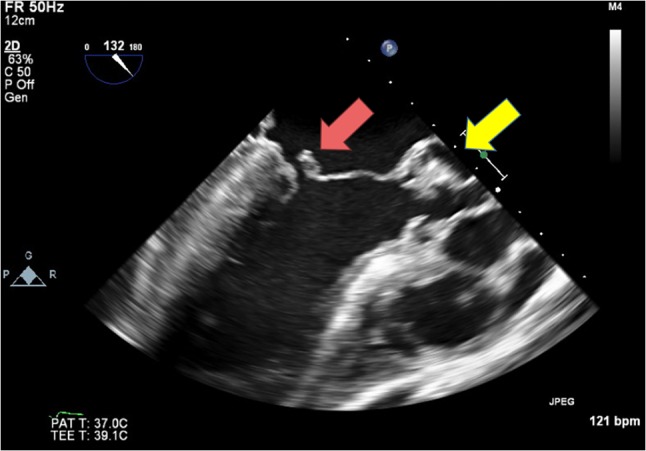

Figure 13:

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing severe aortic valve regurgitation and fistula between aortic sinus and the RVOT.

Figure 14:

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing severe aortic valve regurgitation and fistula between aortic sinus and the RVOT.

Figure 16:

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing fistula between aortic sinus and the RVOT.

Figure 3:

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing vegetations attached to mitral and aortic valves.

Figure 4:

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing severe mitral valve regurgitation.

Figure 9:

3D Transesophageal echocardiogram showing large vegetation attached to the mitral valve.

Figure 10:

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing possible flail mitral valve and large vegetation attached to aortic valve.

Figure 11:

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing vegetations attached to mitral and aortic valves.

DISCUSSION

AD is a rare cause of endocarditis. However, few studies have estimated that AD is responsible for 5–6% of all cases of IE [5]. AD is usually isolated from an immunocompetent host and is a very important cause of blood culture negative IE. It is often seen as a satellite lesion around other bacteria that secrete pyridoxal such as Staphylococcus. AD requires pyridoxine and Vitamin B6 for growth [6]. AD is difficult to identify as it has unique nutritional requirements, is pleomorphic, and is a very slow growing organism. A rapid, yet simple and inexpensive method to identify AD is by using MALDI-TOF-MS (Matrix associated laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrophotometer). AD endocarditis carries higher morbidity and mortality than endocarditis caused by any other streptococci [7]. Multiple factors that add to the virulent nature of this organism are secretion of exopolysaccharide, ability to adhere to fibronectin and a special affinity for endovascular tissue. IE due to AD is also attributed to the preexistence of prior or congenital heart disease and has been reported to cause native and prosthetic valve endocarditis [2, 3].

Despite of the use of appropriate antibiotics, AD endocarditis is known to cause serious complications leading to heart failure, septic embolization and destruction of the valves. The recommended antibiotic treatment for AD endocarditis consists of penicillin or ampicillin with gentamicin for 4–6 weeks, according to the American Heart Association guidelines [8]. In vitro antibiotic susceptibility does not reflect clinical outcome. Heart failure is the most serious complication of endocarditis that often requires valve replacement [9]. Aggressive treatment becomes essential with development of complications, with ~50% of the patients eventually requiring surgical interventions [8].

In our patient, due to a definite embolization potential of the large vegetation and extensive multivalvular damage, a pulmonary, mitral and aortic valve replacement surgery was performed. A multi-disciplinary team comprising of cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, infectious disease specialists and intensive care specialists contributed to the favorable outcome.

In general, Aorto-RV fistulas have been described to occur because of rupture of congenital and acquired sinus of Valsalva aneurysms. Other reported causes that result in aorto-RV fistula include blunt or penetrating chest trauma, aortic dissection, high ventricular septal defect repair and aortic valve surgery. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only case report of AD endocarditis requiring replacement of pulmonary, mitral and aortic valves. This case also stands unique, as it demonstrates an association between Aorto-RV fistula and AD Endocarditis. In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of Abiotrophia endocarditis that involved the aortic, pulmonary and mitral valve without an identified entrance route.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Oxford Medical Case Reports online.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Frenkel A, Hirsch W. Spontaneous development of L forms of streptococci requiring secretions of other bacteria or sulphydryl compounds for normal growth. Nature 1961;191:728–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Christensen JJ, Facklam RR. Granulicatella and Abiotrophia species from human clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:3520–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lainscak M, Lejko-Zupanc T, Strumbelj I, Gasparac I, Mueller- Premru M, Pirs M. Infective endocarditis due to Abiotrophia defectiva: a report of two cases. J Heart Valve Dis 2005;14:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yemisen M, Koksal F, Mete B, Yarimcam F, Okcun B, Kucukoglu S, et al. Abiotrophia defectiva: a rare cause of infective endocarditis. Scand J Infect Dis 2006;38:939–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al-Jasser AM, Enani MA, Al-Fagih MR. Endocarditis caused by Abiotrophia defectiva. Libyan J Med. 2007;2(1):43–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bouvet A. Human endocarditis due to nutritionally variant streptococci: streptococcus adjacens and Streptococcus defectivus. Eur Heart J 1995;16:24–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christensen JJ, Cruhn N, Facklam RR. Endocarditis caused by Abiotrophia species. Scand J Infect Dis 1999;31:210–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baddour L. M., Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG Jr, Bolger AF, Levison ME, et al. Infective endocarditis diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the committee on rheumatic fever, endocarditis, and Kawasaki disease, council on cardiovascular disease in the young, and the councils on clinical cardiology, stroke, and cardiovascular surgery and anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 2005;111.23:e394–e434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cabell CH, Abrutyn E, Karchmer AW. Bacterial endocarditis: the disease, treatment, and prevention. Circulation 2003;107:e185–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.