Summary

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is a life-shortening inherited disease caused by the loss or dysfunction of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel activity resulting from mutations in the CFTR gene. Phe508del is the most prevalent mutation with approximately 90% of CF patients carries it on at least one allele. Over the past 2-3 decades, significant progress has been made in understanding the pathogenesis of CF and development of effective CF therapies. The approval of Orkambi ™ (lumacaftor/ivacaftor) marks another mile stone in CF therapeutics development, and with the advent of personalized medicine, could potentially revolutionize the CF care and management. This article reviews the rationale, progress, and future direction in the development of lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination to treat CF patients homozygous for Phe508del-CFTR.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis (CF), CFTR, CF therapy, CFTR modulation, lumacaftor, ivacaftor

Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF)

CF is a life-shortening inherited disease caused by the loss or dysfunction of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel activity resulting from mutations in the CFTR gene (1, 2). There are about 30,000 CF patients in US and 70,000 worldwide (3). The incidence of CF and the frequency of specific mutations vary among ethnic populations (4, 5). In US, the disease occurs in 1 in 2,500 to 3,500 Caucasian newborns. CF is less common in other ethnic groups, affecting about 1 in 17,000 African Americans and 1 in 31,000 Asian Americans (6).

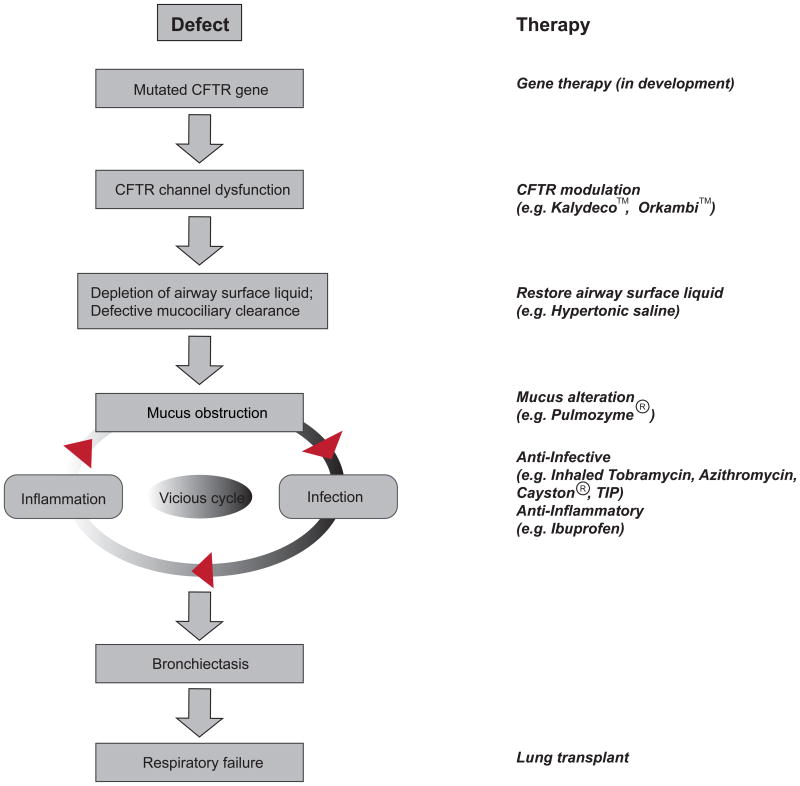

The absence or dysfunction of CFTR channel leads to aberrant ion and fluid homeostasis at epithelial surfaces where it is normally expressed. Clinically, CF affects multiple organs, among which chronic lung disease causes most CF morbidity and mortality. Other symptoms include pancreatic insufficiency, meconium ileus, elevated sweat electrolytes, male infertility, etc (7). In the CF lungs, the loss of CFTR function causes the depletion of airway surface liquid (ASL), mucus plugging of the airways and the failure of mucociliary clearance, and subsequent chronic bacterial infections and excessive inflammation. This causes bronchiectasis and progressive airway destruction, eventually leading to the loss of pulmonary function (Figure1) (8). It should be noted that other genetic and environmental factors also influence the severity of the disease.

Figure 1. The hypothesized pathophysiologic cascade of cystic fibrosis (CF) lung disease.

Genetic and environmental factors can affect the outcome at each step. Shown on the right are therapies designed to correct abnormalities.

CFTR

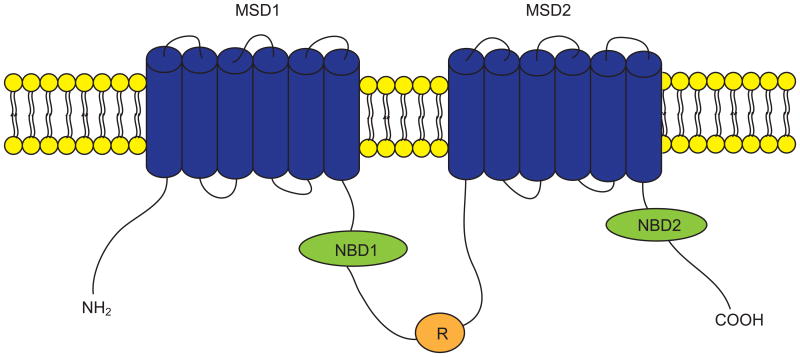

CFTR is a cAMP-and cGMP-regulated chloride (Cl-) and bicarbonate (HCO3-) channel expressed primarily at the apical (luminal) surfaces of epithelial cells lining airways, gut, and exocrine glands, where it is responsible for transepithelial salt and water transport (9-11). CFTR is a member of the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily and consists of 1480 amino acids. CFTR is composed of two membrane-spanning domains (MSD1 and MSD2), two nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2), and a regulatory (R) domain (Figure 2). Both the amino (NH2) and carboxyl (COOH) terminal tails of CFTR mediate its interactions with a wide variety of binding partners (12). CFTR channel can be activated through phosphorylation of the R domain by various protein kinases (e.g., cAMP-dependent protein kinase A) and by ATP binding to and hydrolysis by the NBDs. CFTR channel activity is determined by the quantity of channels at the cell surface, the open probability (Po) of the channels, and the single channel conductance. Mutations in the CFTR gene alter one or more of these parameters, causing the impairment or loss of the channel activity. More than 2000 mutations have been identified in the CFTR gene, which can be roughly grouped into five categories based on the nature of defects (13). Class I mutations constitute nonsense, splice and frame shift mutations that encode truncated forms of CFTR (e.g., Gly542X). Class II mutations encode CFTR proteins that have defect in folding and processing, therefore get trapped in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and targeted for degradation, resulting in no to very little CFTR protein at the cell surface. Phe508del is the most prevalent Class II mutant. Approximately 90% of CF patients carry Phe508del on at least one allele. Class III mutations encode CFTR proteins that have defect in channel gating (regulation mutations; e.g., Gly551Asp) and Class IV mutations encode proteins that have reduced capability to transport Cl- (permeation mutations; e.g., Arg117His). The class V mutations show reduced mRNA stability (e.g., 3849+10kbC→T). The classification of CFTR mutations helps define strategies to restore CFTR channel function based on mutation-specific defect(s).

Figure 2. The putative domain structure of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein.

CFTR is composed of two membrane spanning domains (MSD1 and MSD2), two nucleotide binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2), and a regulatory domain (R). CFTR chloride channel can be activated by phosphorylation of the R domain and by ATP binding to and hydrolysis by NBDs. CFTR channel activity is determined by the number of channels at the cell surface, the open probability of the channels, and the single channel conductance. Mutations in the CFTR gene alter one or more of these parameters, causing the impairment or loss of the channel activity.

CF disease management and therapy

The traditional CF therapies target the downstream disease consequences that are secondary to the ‘root cause’ of the disease: loss of CFTR channel function. The early diagnosis of the disease, development of novel therapies, and the establishment of specialized CF care centers have dramatically improved the outcomes of CF disease management. Today, half of people with CF age 18 or older and CF life expectancy has increased to nearly 38 years (14). The currently available therapies include: restoration of ASL (e.g., hypertonic saline), mucus alteration (e.g., Pulmozyme®), anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., Ibuprofen), anti-infective agents (e.g., TOBI®, Azithromycin, Cayston®, TIP (TOBI inhaled powder), nutrition (AquADEKs, Pancrelipase Enzyme Products), and lung transplantation (Figure 1) (15). Because the defective CFTR channel is the ‘root cause’ of CF disease, targeting CFTR gene and/or protein (CFTR modulation) holds great promise for CF therapy. In addition to pursuing gene therapy, efforts have been taken to correct/rescue the defects of CFTR channel using pharmacological agents (16-18). Dated back to 1998, US CF Foundation started a bold move to establish collaboration with pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs targeting mutant CFTRs, which has come to fruit with two drugs, Kalydeco™ (targeting Gly551Asp and other Class III-IV mutions) and Orkambi™ (targeting Phe508del), approved by regulatory agents and other drug candidates in development (15). The advent of precision CFTR modulators has the potential to fundamentally change CF disease management.

Personalized therapy of CF

It is well known that the pulmonary disease phenotypes do not correlate well with CFTR genotypes and that genetic (e.g., CF modifier genes) and environmental factors cause the variations of the disease manifestations (8). Although the use of heterologous expression system (e.g., Fischer rat thyroid (FRT) cells, HEK293 cells) can give an indication whether a CFTR modulator (or a combination of CFTR modulators) works on specific mutations, it cannot predict an actual effect on individual patients. This problem can be partially overcome by testing these modulators on native epithelia or primary cell cultures obtained from individual patients (19). Some of the successful examples include: (1) harvesting rectal biopsies from individual CF patients and measurement of CFTR-mediated currents using Ussing chamber assay (20); (2) conversion of rectal biopsies into organoids on Matrigel and measurement of CFTR-mediated organoid swelling (21). The development of personalized samples and sensitive CFTR channel function testing assays makes it possible to define optimal drug treatment effects in pre-clinical settings for individual patients and ultimately help to define an optimal therapy.

Lumacaftor and Ivacaftor

Lumacaftor

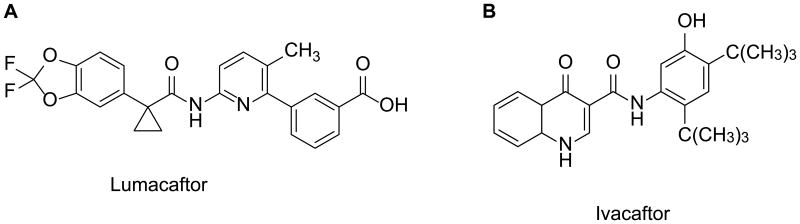

Lumacaftor (also called VX-809; Figure 3A) is a CFTR corrector discovered through high throughput screening (HTS) followed by lead optimization. In FRT cells, lumacaftor improved Phe508del-CFTR maturation by 7.1 ± 0.3-fold and increased Phe508del-CFTR-mediated short-circuit currents (Isc) by approximately 5-fold. In primary human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells isolated from the lungs of seven patients homozygous for Phe508del, lumacaftor increased CFTR maturation by approximately 8-fold and CFTR-mediated Isc by 4-fold (equivalent to ∼14% of non-CF HBE). Lumacaftor-corrected Phe508del-CFTR exhibited biochemical and functional characteristics similar to wild-type (WT)-CFTR (22). Mechanistic studies suggested that lumacaftor acts by directly interacting with Phe508del-CFTR and promoting its proper folding during biogenesis and processing in the ER (23, 24). In addition to Phe508del, lumacaftor also rescued the maturation of other mutations (e.g., Gly1208Asp) (24, 25).

Figure 3. Chemical structures of (A) lumacaftor and (B) ivacaftor.

A 28-day phase IIa trial of lumacaftor in adult Phe508del homozygous patients (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00865904) demonstrated a safe profile of lumacaftor and reduced sweat Cl- levels. However, no significant changes in lung function or patient-reported outcomes were observed (26). The study suggested that a combination of lumacaftor with ivacaftor might be necessary to improve the clinical effects of these CFTR modulators on patients with Phe508del mutation.

Ivacaftor

Ivacaftor (also called VX-770; Figure 3B) is a CFTR potentiator identified from HTS followed by lead optimization. Ivacaftor potentiated Gly551Asp-CFTR-mediated Isc in FRT cells by ∼4-fold and temperature-corrected Phe508del-CFTR by ∼6-fold. Ivacaftor increased CFTR channel Po in excised membrane patches from these recombinant cells (Gly551Asp: ∼6-fold; WT: 2-fold; Phe508del: ∼5-fold). In primary cultures of HBE (Gly551Asp / Phe508del), ivacaftor increased CFTR-mediated Isc by 10-fold (equivalent of 48 ± 4% of non-CF HBE). In HBEs isolated from three of the six Phe508del-homozygous CF patients, ivacaftor significantly increased the CFTR-mediated Isc with a maximum response equivalent to 16 ± 4% of non-CF HBE. The ivacaftor-elicited increase in CFTR-mediated Cl- secretion caused a secondary decrease in ENaC-mediated Na+ absorption and consequently increased the ASL volume and cilia beating in Gly551Asp/Phe508del HBEs (27). Mechanistic studies suggested that ivacaftor binds directly to CFTR, possibly on MSDs, and stabilizes an O2 channel open state and promotes channel gating (28, 29). In addition to its potentiating effect on Gly551Asp, ivacaftor also augmented the channel function of a panel of other Class III and IV mutations including Arg117His, Ser549Asn, Ser549Arg, Gly551Ser, Gly970Arg etc. (30-32).

In a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00909532) to evaluate ivacaftor in CF patients with at least one Gly551Asp mutation and aged 12 years or older, it was found that, compared to placebo-controlled group, ivacaftor treatment group (1) showed improvement in lung function, with a change from baseline through Week 24 in the percent of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) greater by 10.6%; the treatment effect was noted at Week 2 and maintained through Week 48; (2) had lower pulmonary exacerbation risk (55%); (3) through Week 48, had better score (8.6%) on the respiratory-symptoms domain of the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised (CFQ-R) instrument, suggesting an improvement in quality of life; (4) By Week 48, had an average of 2.7 kg weight gain; (5) had reduced sweat chloride levels (an average of -48.1 mmol/L change from baseline through Week 48), indicating an improvement in CFTR channel function (33).

A following clinical study (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00909727) found that in CF patients aged 6-11 years and have at least one Gly551Asp mutation, ivacaftor significantly improved pulmonary function (treatment effect: 12.5%) and the weight gain (2.8 kg on average), and reduced sweat chloride levels (an average of -53.5 mmol/L change from baseline through week 48) (34).

In a longitudinal cohort study in subjects aged 6 and older with Gly551Asp (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01521338), Rowe et al found that ivacaftor significantly improved the lung function, body mass index (BMI), mucociliary clearance, gastrointestinal pH, and microbiome, and significantly reduced hospitalization rate and P. aeruginosa burden. The study shines light on the mechanisms underlying the clinical benefit of ivacaftor on CF respiratory and GI disease (35).

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ivacaftor (under the brand name Kalydeco™) on January 31, 2012 to treat people with CF aged 6 and older with the Gly551Asp mutation. It is the first drug available to target the underlying cause of CF and demonstrated that CFTR is a validated drug target for CF therapy. Since then, FDA has approved the expanded use of Kalydeco™ for people with Gly178Arg, Ser549Asn, Ser549Arg, Gly551Ser, Gly1244Glu, Ser1251Asn, Ser1255Pro, Gly1349Asp and Arg117His mutations (15).

Lumacaftor/Ivacaftor Combination Therapy for Phe508del-CFTR

Combination of lumacaftor and Ivacaftor

Phe508del-CFTR protein has multiple defects: it has a folding defect, which causes the protein trapped in the ER and targeted for degradation, resulting in little to no protein at the cell surface. Although the mutant protein can be partially rescued by exposure to low temperature, it is unstable at the cell surface and exhibits impaired channel activity. A combination of CFTR corrector with potentiator seems needed to circumvent these defects. Van Goor et al. found that acute application of ivacaftor increased the lumacaftor-corrected Phe508del-CFTR-mediated Isc in cultured HBEs (to a level of ∼25% of non-CF HBEs) and further increased ASL height in these cells. The data supported the rational of combining CFTR correctors and potentiators as one strategy for CF therapy (22).

In a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, 3-successive-cohort study in subjects having a Phe508del mutation (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01225211), it was found that lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination improved the FEV1 for patients homozygous for Phe508del and reduced the sweat chloride levels, and that combination therapy had a similar proportion of adverse events as placebo (36). This study provided the first evidence of the effectiveness of lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination for Phe508del-homozygous patients and set the stage for further investigation in larger and long-term studies.

In two following phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (TRAFFIC and TRANSPORT, ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01807923 and NCT01807949, respectively) to test the effects of lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination in patients aged 12 years or older and have two copies of Phe508del, compared to placebo-controlled groups, drug combination treatment groups showed (1) significant improvements in the primary end-point, the absolute change from baseline in the percentage of predicted FEV1 at Week 24, with mean absolute improvements of 2.6-4.0%; (2) 30-39% lower of pulmonary exacerbation rate; and (3) similar incidence profile of adverse events (37). In July, 2015, US FDA approved the drug combination (under the brand name Orkambi™) for CF patients homozygous for Phe508del mutation and are 12 years and older (15).

Ongoing clinical trials using lumacaftor and ivacaftor

Two ongoing trials are under way using lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination:

A phase 3b, open-label study to evaluate lumacaftor/ ivacaftor combination therapy in CF subjects who are homozygous for Phe508del, 12 years and older, and have advanced lung disease (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT02390219). The primary outcome measure of this study is to assess the safety and tolerability of combination therapy. The secondary outcome measures include: pulmonary function changes (e.g., absolute change from baseline in percent predicted FEV1 at each visit up to Week 24; pulmonary exacerbation rate; hospitalization rate; absolute change from baseline to average Day 15 and Week 4 sweat chloride levels; absolute change form baseline in CFQ-R through Week 24 (38).

A phase 3, double- blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lumacaftor/ ivacaftor in subjects aged 6 through 11 years who are homozygous for Phe508del (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT02514473). The primary outcome measure is the absolute change from baseline through Week 24 in lung clearance index. The study will also test the changes in percent predicted FEV1; CFQ- R respiratory domain score; sweat chloride; BMI; pulmonary exacerbation event etc. (39).

Some issues (or concerns) associated with Orkambi™

Orkambi™ has a very high price tag, which costs around $ 258,000 per year for each patient in US. Although it is slightly lower than Kalydeco™, it is still one of the most expensive drugs (40). The cost could place a heavy financial burden on individual CF patients and affect public health system. Another notable issue is its efficacy: compared to the effects of Kalydeco™ on Gly551Asp CF patients, the clinical outcomes of Orkambi™ were modest, which could be attributed to several factors: (1) a possible drug-drug interaction between lumacaftor and ivacaftor. Several recent in vitro studies demonstrated that ivacaftor interfered with the effect of lumacaftor on Phe508del-CFTR channel function (41, 42). Other drugs in combination could avoid this adverse interaction and some other potentiators that do not interfere with corrector action has been reported (43); (2) Combination of the two drugs. The clinical outcomes could be improved by using personalized and optimal drug combination for individual patients instead of a fixed combination (44).

Conclusions

Over the past 20-30 years, significant progress has been made in understanding the CF pathogenesis and development of effective CF therapies, which has dramatically increased the life expectancy of people with CF. The approval of CFTR modulators, Kalydeco™ (ivacaftor) and Orkambi ™ (lumacaftor/ivacaftor), marks two mile stones in our pursuit of ‘a cure’ for people suffering from CF. With the technological advancements in drug discovery and personalized medicine, we have reasons to believe that the future is bright for effective and personalized CF therapies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: DK080834 and DK093045 (to Anjaparavanda P. Naren), HL123535 (to Weiqiang Zhang). We thank Dr. Amanda Preston (Scientific Editor, Children's Foundation Research Institute, Le Bonheur Children's Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA) for editing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ASL

airway surface liquid

- BMI

body mass index

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFQ-R

Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire – Revised

- CFTR

CF transmembrane conductance regulator

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FRT cells

Fischer rat thyroid cells

- HBEs

human bronchial epithelial cells

- HTS

high throughput screening

- MSD

membrane-spanning domain

- NBD

nucleotide binding domain

- Po

open probability

- R

regulatory domain

- Isc

short-circuit currents

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors state no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, et al. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1990;63(4):827–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Molecular mechanisms of CFTR chloride channel dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1993;73(7):1251–1254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90353-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. [Accessed February 1, 2016]; [US]: https://www.cff.org/What-is-CF/About-Cystic-Fibrosis/

- 4.Rohlfs EM, Zhou Z, Heim RA, et al. Cystic fibrosis carrier testing in an ethnically diverse US population. Clin Chem. 2011;57(6):841–848. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.159285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugarman EA, Rohlfs EM, Silverman LM, et al. CFTR mutation distribution among Hispanic US and African American individuals: evaluation in cystic fibrosis patient and carrier screening populations. Genet Med. 2004;6(5):392–399. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000139503.22088.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genetics Home Reference. [Accessed February 1, 2016]; http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/cystic-fibrosis.

- 7.Davies JC, Alton EW, Bush A. Cystic fibrosis. BMJ. 2007;335(7632):1255–1259. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39391.713229.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsey BW, Banks-Schlegel S, Accurso FJ, et al. Future directions in early cystic fibrosis lung disease research: an NHLBI workshop report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(8):887–892. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2068WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245(4922):1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, et al. Demonstration that CFTR is a chloride channel by alteration of its anion selectivity. Science. 1991;253(5016):202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bear CE, Li CH, Kartner N, et al. Purification and functional reconstitution of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cell. 1992;68(4):809–818. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, Naren AP. CFTR chloride channel in the apical compartments: spatiotemporal coupling to its interacting partners. Integr Biol (Camb) 2010;2(4):161–177. doi: 10.1039/b924455g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clancy JP, Jain M. Personalized medicine in cystic fibrosis: dawning of a new era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(7):593–597. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0785PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. [Accessed February 1, 2016]; [US]: https://www.cff.org/What-is-CF/Diagnosed-with-Cystic-Fibrosis/

- 15.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. [Accessed February 1, 2016]; [US]: https://tools.cff.org/research/drugdevelopmentpipeline/

- 16.Sermet-Gaudelus I, Boeck KD, Casimir GJ, et al. Ataluren (PTC124) induces cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein expression and activity in children with nonsensemutation cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(10):1262–1272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0137OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phuan PW, Yang B, Knapp J, et al. Cyanoquinolines with independent corrector and potentiator activities restore deltaF508-CFTR chloride channel function in cystic fibrosis. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80(4):683–693. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.073056. 80(4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedemonte N, Tomati V, Sondo E, et al. Dual activity of aminoarylthiazoles on the trafficking and gating defects of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel caused by cystic fibrosis mutations. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(17):15215–15226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikpa PT, Bijvelds MJ, de Jonge HR. Cystic fibrosis: toward personalized therapies. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;52:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clancy JP, Szczesniak RD, Ashlock MA, et al. Multicenter intestinal current measurements in rectal biopsies from CF and non-CF subjects to monitor CFTR function. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dekkers JF, Wiegerinck CL, de Jonge HR, et al. A functional CFTR assay using primary cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. Nat Med. 2013;19(7):939–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, et al. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(46):18843–18848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha C, Zhang W, Moon CS, et al. Capturing the Direct Binding of CFTR Correctors to CFTR by Using Click Chemistry. Chembiochem. 2015;16(14):2017–2022. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren HY, Grove DE, De La Rosa O, et al. VX-809 corrects folding defects in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein through action on membrane-spanning domain 1. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(19):3016–3024. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-05-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Hothi JS, Zhang YH, et al. c.3623G> A mutation encodes a CFTR protein with impaired channel function. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clancy JP, Rowe SM, Accurso FJ, et al. Results of a Phase IIa study of VX-809, an investigational CFTR corrector compound, in subjects with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation. Thorax. 2011;67(1):12–18. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, et al. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(44):18825–18830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904709106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckford PD, Li C, Ramjeesingh M, et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) potentiator VX-770 (ivacaftor) opens the defective channel gate of mutant CFTR in a phosphorylation-dependent but ATP-independent manner. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(44):36639–36649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.393637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jih KY, Hwang TC. Vx-770 potentiates CFTR function by promoting decoupling between the gating cycle and ATP hydrolysis cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(11):4404–4409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215982110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Goor F, Yu H, Burton B, et al. Effect of ivacaftor on CFTR forms with missense mutations associated with defects in protein processing or function. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu H, Burton B, Huang CJ, et al. Ivacaftor potentiation of multiple CFTR channels with gating mutations. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11(3):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yarlagadda S, Zhang W, Penmatsa H, et al. A young Hispanic with c.1646G>A mutation exhibits severe cystic fibrosis lung disease: is ivacaftor an option for therapy? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(7):694–696. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.186.7.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1663–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies JC, Wainwright CE, Canny GJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivacaftor in patients aged 6 to 11 years with cystic fibrosis with a G551D mutation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(11):1219–1225. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0153OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowe SM, Heltshe SL, Gonska T, et al. Clinical mechanism of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator potentiator ivacaftor in G551D-mediated cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(2):175–184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0703OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyle MP, Bell SC, et al. A CFTR corrector (lumacaftor) and a CFTR potentiator (ivacaftor) for treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis who have a phe508del CFTR mutation: a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(7):527–538. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wainwright CE, Elborn JS, Ramsey BW, et al. Lumacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis Homozygous for Phe508del CFTR. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):220–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02390219?term=vx+809. Accessed February 1, 2016.

- 39.https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02514473?term=809-109&rank=1. February 1, 2016

- 40.Ferkol T, Quinton P. Precision Medicine: At What Price? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(6):658–659. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1428ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veit G, Avramescu RG, Perdomo D, et al. Some gating potentiators, including VX-770, diminish ΔF508-CFTR functional expression. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(246):246ra97. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cholon DM, Quinney NL, Fulcher ML, et al. Potentiator ivacaftor abrogates pharmacological correction of ΔF508 CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(246):246ra96. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phuan PW, Veit G, Tan JA, et al. Potentiators of Defective ΔF508-CFTR Gating that Do Not Interfere with Corrector Action. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;88(4):791–799. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.099689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis PB. Another Beginning for Cystic Fibrosis Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):274–276. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1504059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]