Summary

The opportunistic fungal pathogen, Aspergillus fumigatus invades pulmonary epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells by inducing its own endocytosis, but the mechanism by which this process occurs is poorly understood. Here, we show that the thaumatin-like protein CalA is expressed on the surface of the A. fumigatus cell wall where it mediates invasion of epithelial and endothelial cells. CalA induces endocytosis in part by interacting with integrin α5β1 on host cells. In corticosteroid-treated mice, a ΔcalA deletion mutant has significantly attenuated virulence relative to the wild-type strain, as manifested by prolonged survival, reduced pulmonary fungal burden, and decreased pulmonary invasion. Pretreatment with an anti-CalA antibody improves survival of mice with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, demonstrating the potential of CalA as an immunotherapeutic target. Thus, A. fumigatus CalA is an invasin that interacts with integrin α5β1 on host cells, induces endocytosis, and enhances virulence.

Aspergillus fumigatus is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes invasive pneumonia and hematogenously disseminated infections in immunocompromised patients1,2. Invasive aspergillosis is initiated by inhalation of conidia, which are deposited in the alveoli. In the absence of an effective host immune response, these inhaled conidia germinate to form filamentous hyphae that invade the alveolar epithelial cells into the blood vessels. Angioinvasion results in thrombosis and tissue infarction, a characteristic feature of invasive aspergillosis3. A. fumigatus invades both pulmonary epithelial and vascular endothelial cells by the process of induced endocytosis4-9. This process is likely initiated by the binding of a fungal invasin to a host cell receptor, which then stimulates the host cell to form pseudopods that engulf the organism and pull it into the cell10. However, prior to the current work, the identities of the fungal invasin(s) and cognate host cell receptor(s) that induce host cell endocytosis were unknown.

A. fumigatus CalA is predicted by bioinformatic analysis to be an adhesin protein. Also, recombinant CalA produced in Escherichia coli binds to laminin and mouse splenocytes and to pulmonary epithelial cells11, suggesting that CalA may have adhesive properties. We set out to determine the function of A. fumigatus CalA in host cell adherence and invasion, identify its host cell target, and investigate its role in virulence.

CalA is expressed on the cell surface of A. fumigatus, but is dispensable for adherence

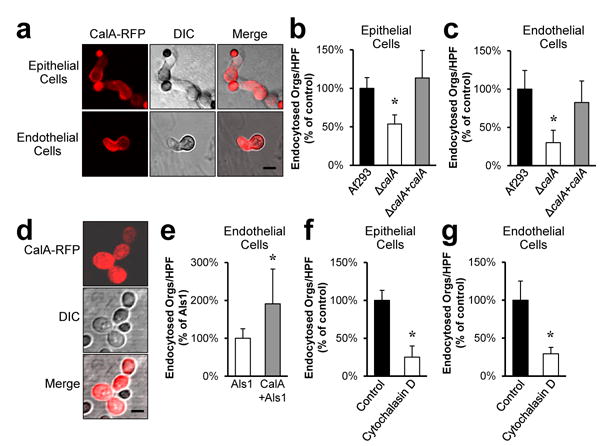

For CalA to function as an adhesin, it must be expressed on the cell surface. To analyze the surface expression of CalA, we constructed a strain of A. fumigatus that expressed a CalA-RFP fusion protein. By confocal microscopy, we determined found that CalA was strongly expressed on the surface of germlings that were in contact with either A549 pulmonary epithelial cell line and primary vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 1a). The surface expression of CalA was confirmed by staining with an anti-CalA antibody (Supplementary Fig. 1). CalA was also expressed on the surface of swollen conidia (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 1. A. fumigatus CalA functions as an invasin.

a, Confocal microscopic images of A549 pulmonary epithelial cells (top) and vascular endothelial cells (bottom) infected for 2.5 h with A. fumigatus Af293 expressing CalA-RFP. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Images of control A. fumigatus cells that expressed RFP alone are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a. Scale bar, 5 μm. b and c, The indicated strains of A fumigatus were incubated with A549 pulmonary epithelial cells (b) or vascular endothelial cells (c) for 2.5 h, after which the number of endocytosed organisms was determined by a differential fluorescence assay. Result are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments, each performed in triplicate. *p < 0.001 compared to Af293 and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). HPF, high-powered field. d, Confocal microscopic images of a strain of S. cerevisiae expressing both C. albicans Als1 and A. fumigatus CalA-RFP. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar, 5 μm. e, S. cerevisiae strains expressing either Als1 alone or both Als1 and CalA were incubated with endothelial cells for 2.5 h, after which the number of endocytosed organisms was determined. Result are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.005 compared to S. cerevisiae expressing Als1 alone (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). f and g, Effect of cytochalasin D on the invasion of A fumigatus Af293 in to A549 epithelial cells (f) and endothelial cells (g). Result are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.001 compared to cell incubated with the diluent alone (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances).

To investigate the function of A fumigatus CalA, we constructed a mutant in which the calA protein coding region was deleted and then tested the adherence of this strain. The adherence of the ΔcalA mutant to both A549 epithelial cells and immobilized laminin was similar to the wild-type strain (Supplementary Fig. 3a-d). In addition, the ΔcalA mutant had wild-type adherence to fluid-phase laminin (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Both the ΔcalA mutant and wild-type strain produced similar levels of galactosaminogalactan (Supplementary Fig. 4), a cell wall carbohydrate that mediates adherence of A. fumigatus to host constituents and masks surface exposed β1,3-glucans12. Therefore, under the conditions tested, CalA is dispensable for A. fumigatus adherence to both epithelial cells and laminin.

CalA functions as an invasin

Next, we considered the possibility that although CalA is dispensable for adherence, it may function as an invasin that induces host cell endocytosis of A. fumigatus. Using our standard differential fluorescent assay in serum-free medium6,13, we determined that 47% fewer germlings of the ΔcalA mutant were endocytosed by A549 pulmonary epithelial cells as compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 1b). In addition, 70% fewer ΔcalA mutant cells were endocytosed by endothelial cells (Fig. 1c). Importantly, the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain was endocytosed by both cell types similarly to wild-type A. fumigatus, demonstrating that the invasion defect of the ΔcalA mutant was due to the absence of CalA. Collectively, these results indicate that CalA is required for maximal host cell invasion by A. fumigatus.

To determine if CalA can directly mediate host cell invasion, we heterologously expressed a CalA-RFP fusion protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which does not normally adhere to or invade epithelial or endothelial cells14. Imaging by confocal microscopy verified that CalA-RFP was expressed on the cell surface of S. cerevisiae (Fig. 1d). This strain did not adhere to either epithelial or endothelial cells, consistent with our finding that CalA does not function as an adhesin. Because an organism must adhere to a host cell before it can induce its own endocytosis, the strain expressing only CalA was not endocytosed. To determine if CalA could induce endocytosis after adherence had occurred, we expressed CalA in a S. cerevisiae strain that also expressed Candida albicans Als1, a protein that mediates adherence to endothelial cells but induces minimal endocytosis14,15. Expression of CalA in the Als1-expressing strain of S. cerevisiae resulted in a 2-fold increase in the number of yeast cells that were endocytosed by endothelial cells as compared to the control strain that expressed Als1 alone (Fig. 1e). Of note, the capacity of the CalA-Als1 expressing strain to be endocytosed by A549 pulmonary epithelial cells could not be tested because strains of S. cerevisiae that expressed Als1 did not adhere to these cells. Overall, these data indicate that CalA functions as an invasin in adherent fungal cells.

In addition to invading host cells by induced endocytosis, some fungi can invade host cells by active penetration, a process in which elongating hyphae physically push their way into host cells10. To determine the relative roles of induced endocytosis and active penetration in A. fumigatus invasion, we treated A549 epithelial cells and endothelial cells with cytochalasin D, which depolymerizes microfilaments and blocks induced endocytosis. We found that cytochalasin D reduced A. fumigatus invasion of these host cells by approximately 75% (Fig. 1f, g), indicating that the fungus invades epithelial and endothelial cells mainly by the process of induced endocytosis.

Germination and stress response of the ΔcalA mutant

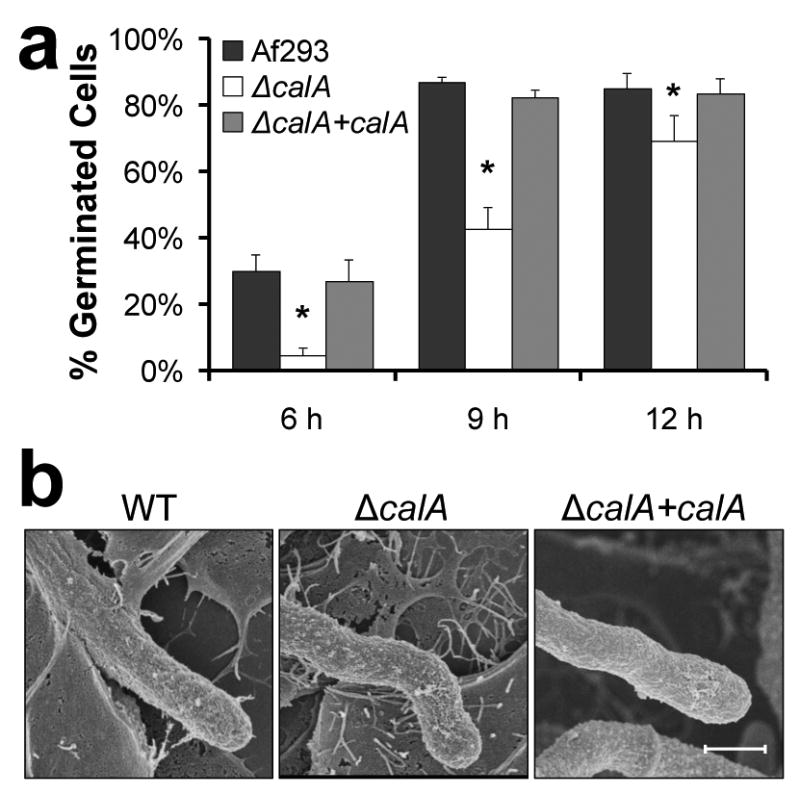

In A. nidulans, AnCalA is required for normal conidial germination16. Therefore, we asked whether deletion of calA affected the germination of A. fumigatus and discovered that the germination of this mutant was dependent on the growth condition. When the organisms were germinated in Sabauroud broth on polystyrene petri dishes, the ΔcalA mutant germinated similarly to the wild-type strain. In contrast, the ΔcalA mutant had delayed germination when grown in tissue culture medium in contact with A549 epithelial cells (Fig. 2a). This germination delay was most apparent after 6 h and largely resolved by 12 h.

Figure 2. CalA is required for normal germination and hyphal morphology.

a, Germination of the indicated A. fumigatus strains on A549 pulmonary epithelial cells. Results are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments, each of which analyzed at least 100 cells per strain in triplicate. *p < 0.01 compared to Af293 or the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). b, Scanning electron micrographs of the indicated strains after they were germinated for 18 h in RPMI 1640 medium and then incubated with A549 epithelial cells for 6 h. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Next, we used scanning electron microscopy to examine the morphology of hyphae of the ΔcalA mutant. We observed that when the wild-type and ΔcalA+calA complemented strains were grown on pulmonary epithelial cells, they produced straight hyphae, whereas the ΔcalA mutant consistently produced hyphae with curved distal ends (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, this morphologic change was also observed when ΔcalA hyphae were grown in contact with glass coverslips that had been coated with positively charged poly-D-lysine, but not when the organisms were grown on negatively charged glass coverslips (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, CalA influences hyphal morphology under some conditions.

Finally, we investigated whether deletion of calA influenced virulence-related phenotypes. We found that the radial growth and conidiation of the ΔcalA mutant were similar to the wild-type strain. Also, deletion of calA did not affect susceptibility to a variety of stressors, including Congo red, calcofluor white, caspofungin, SDS, H2O2, and protamine (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, the ΔcalA mutant was killed similarly to the wild-type strain by macrophage-like and neutrophil-like HL-60 cells (Supplementary Fig. 7). Therefore, deletion of calA does not have a detectable effect on growth rate, stress response, or susceptibility to phagocyte killing.

Integrin β1 is a host cell receptor for CalA

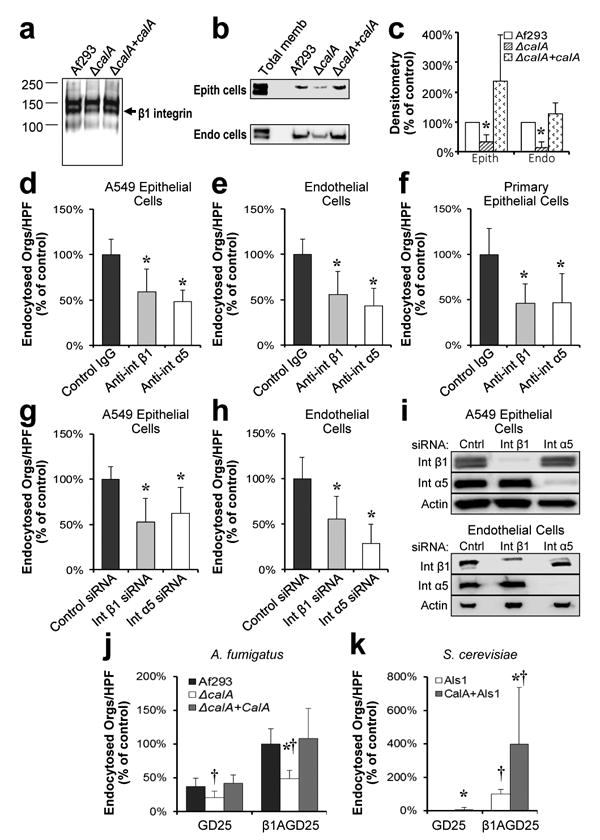

Next, we sought to identify the host cell receptor for CalA using a whole-cell affinity purification approach in which biotinylated cell membrane proteins from A549 epithelial cells were incubated with intact hyphae13,17. The wild-type strain and ΔcalA+calA complemented strain bound to proteins with molecular masses of approximately 160, 130, and 100 kDa (Fig. 3a). While the ΔcalA mutant bound to the 160 and 100 kDa proteins similarly to the wild-type and ΔcalA+calA complemented strains, it bound less strongly to the 130 kDa protein. Therefore, this band was selected for protein sequencing, which revealed the presence of β1 integrin. Immunoblotting with an anti-integrin β1 antibody confirmed that membrane extracts from both pulmonary epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells contained integrin β1 and that this protein was strongly bound by wild-type A. fumigatus (Fig. 3b). Integrin β1 appeared to be bound less avidly by germlings of the ΔcalA mutant (Fig. 3b). By densitometric analysis of replicate immunoblots, the ΔcalA mutant bound 64% and 86% less integrin β1 in epithelial cells and endothelial cells, respectively, as compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 3c). Thus, A. fumigatus interacts, either directly or indirectly, with integrin β1.

Figure 3. β1 integrin binds to A. fumigatus and is require for maximal endocytosis.

a, Immunoblot of biotin-labeled A549 epithelial cell membrane proteins that had been eluted from hyphae of the indicated strains of A fumigatus. Blot was probed with an anti-biotin antibody. Arrow indicates the band containing β1 integrin. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. b, Immunoblot of membrane proteins from A549 epithelial (epith) cells (top) and vascular endothelial (endo) cells (bottom) that had been eluted from the indicated A. fumigatus strains. Blots were probed with an antibody against β1 integrin (Total memb, total membrane). c, Densitometric analysis of 5 immunoblots from A549 cells and 3 immunoblots from endothelial cells as in (b). *P < 0.04 vs. Af293 and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). d-f, Effects of antibodies against integrin β1 (int β1) and α5 (int α5) on the endocytosis of wild-type A. fumigatus by A549 pulmonary epithelial cells (d) primary vascular endothelial cells (e), and primary human alveolar epithelial cells (f). Results are the mean ± SD of three experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.001 vs. control IgG (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). HPF, high-powered field. g-h, Effects of siRNA knockdown of integrin β1 and α5 on the endocytosis of wild-type A. fumigatus by A549 pulmonary epithelial cells (g) and primary vascular endothelial cells (h). Results are the mean ± SD of three experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.005 vs. control siRNA (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). i, Immunoblots of whole cell lysates showing siRNA knockdown of integrin β1 and α5. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. j-k, Endocytosis of the indicated strains of A. fumigatus (j) and S. cerevisiae expressing ALS1 alone (ALS1) or ALS1 and calA (ALS1+calA) (k) by the GD25 (integrin β1 deficient) and β1AGD25 (integrin β1 restored) cell lines. Results are the mean ± SD of three experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.005 vs. the same strain on GD25 cells, † p < 0.01 vs. A. fumigatus Af293 or Als1-expressing S. cerevisiae on the same host cell line (two-tailed Student's t -test assuming unequal variances).

To determine the functional significance of the interaction between A. fumigatus and β1 integrin, we tested the effects of an anti-β1 integrin monoclonal antibody on host cell endocytosis. This antibody inhibited the endocytosis of A. fumigatus by the A549 pulmonary epithelial cell line, primary vascular endothelial cells, and primary human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells by approximately 50% (Fig. 3d-f). A similar reduction in A. fumigatus endocytosis was observed when integrin β1 in A549 epithelial cells and endothelial cells was knocked down by siRNA (Fig. 3g-i). These results indicate that integrin β1 is necessary for the maximal endocytosis of A. fumigatus by both pulmonary epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells.

To confirm the role of integrin β1 in mediating the endocytosis of A. fumigatus, we used the GD25 fibroblast cell line, which was generated from an integrin β1-/- mouse, and the β1AGD25 cell line, which was made by transfecting GD25 cells with mouse integrin β1 cDNA18. Integrin β1-deficient GD25 cells poorly endocytosed wild-type A. fumigatus, the ΔcalA mutant, and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strains (Fig. 3j). By contrast, the integrin β1-expressing β1AGD25 cells endocytosed significantly more cells of the wild-type and ΔcalA+calA complemented strains, but far fewer cells of the ΔcalA mutant. Similarly, GD25 cells endocytosed very few S. cerevisiae cells that expressed Als1 with or without CalA, whereas β1AGD25 cells avidly endocytosed S. cerevisiae cells that expressed both Als1 and CalA (Fig. 3k). Collectively, these results indicate that CalA interacts with integrin β1 and induces host cell endocytosis.

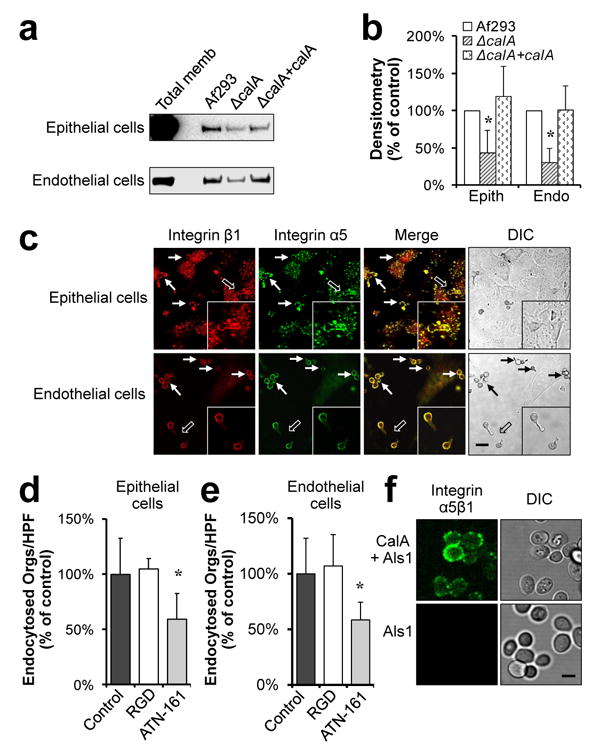

Integrin α5β1 mediates host cell endocytosis of A. fumigatus

Because integrins function as heterodimers19, we sought to identify which integrin α subunit combined with integrin β1 to mediate the endocytosis of A fumigatus. By testing antibodies against different α integrins for their capacity to block endocytosis, we found that an antibody directed against integrin α5 significantly inhibited the endocytosis of A. fumigatus by A549 epithelial cells, primary vascular endothelial cells, and primary human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. 3d-f). To confirm these results, we determined that siRNA knockdown of integrin α5 also inhibited the endocytosis of A. fumigatus by both A549 epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 3g-i). These findings were specific to integrin α5, because siRNA knockdown of integrin α3 had no effect on the endocytosis of A fumigatus by either cell type (Supplementary Fig. 8). In addition, siRNA knockdown of both integrin α5 and β1 did not inhibit endocytosis more than knockdown on integrin α5 alone (Supplementary Fig. 9). We also found that A. fumigatus hyphae bound to integrin α5 in membrane extracts from A549 epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells, and that maximal binding appeared to require the presence of CalA (Fig. 4a, b). Moreover, confocal imaging demonstrated that A. fumigatus germlings were surrounded by both integrin α5 and β1 during endocytosis by host cells (Fig. 4c). These combined data indicate that integrin α5β1 mediates host cell endocytosis of A. fumigatus.

Figure 4. Integrin α5β1 interacts with A. fumigatus CalA.

a, Immunoblots of cell membrane proteins from A549 epithelial cells (top) and vascular endothelial cells (bottom) that had been eluted from the indicated strains of A. fumigatus. Blots were probed with an antibody against integrin α5. b, Densitometric analysis of 4 immunoblots of samples from A549 cells and 3 immunoblots of samples from endothelial cells, such as the ones in (a). *P < 0.04 vs. Af293 and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). c, Confocal microscopic images showing the accumulation of integrin α5β1 integrin around A. fumigatus during infection of A549 epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Thin arrows indicate the accumulation of integrin around the organisms. Hollow arrows indicate the organisms that are shown at higher magnification in the insets. Scale bar, 20 μm. d,e, Effects of the indicated peptides (50 μm) on the endocytosis of A fumigatus by epithelial cells (d) and endothelial cells (e). Results are the mean ± SD of three experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < 0.01 vs. control or cells incubated with the RGD peptide (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). HPF, high-powered field. f, Images of S. cerevisiae cells expressing either CalA and Als1 or Als1 alone that were incubated with recombinant integrin α5β1 and the stained with an anti-integrin α5 antibody. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Next, we verified that integrin α5β1 was bound by other clinical isolates of A fumigatus and mediated their endocytosis. Germlings of two additional clinical isolates were found to bind to integrin α5β1 in membrane extracts from A549 epithelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Moreover, the anti-integrin β1 antibody significantly inhibited the endocytosis of these strains (Supplementary Fig. 10b). Therefore, the capacity of A. fumigatus to interact with integrin α5β1 and induce endocytosis appears to be a common feature of this fungus.

Some bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Mycobacterium avium20-22 invade host cells by binding to fibronectin, which acts as a bridging molecule between the organism and integrin α5β1. To investigate whether CalA interacts directly or indirectly with integrin α5β1, we tested the effects of an RGD peptide that inhibits fibronectin-mediated endocytosis of M. avium20. This peptide did not reduce the endocytosis of A fumigatus, in contrast to a peptide that blocked the fibronectin synergy site of integrin α5β123,24 (Fig. 4d, e). Furthermore, to demonstrate a direct interaction between CalA and integrin α5β1, we incubated S. cerevisiae expressing CalA and/or Als1 with recombinant integrin α5β1. Using indirect immunofluorescence, we observed that the integrin bound avidly to the cells expressing CalA, but not to the cells that did not (Fig. 4f). Collectively, these results indicate that CalA mediates endocytosis by directly binding to a region of integrin α5β1 that is distinct from the RGD binding site.

CalA is required for maximal virulence

The finding that CalA mediates host cell invasion in vitro suggested that CalA contributes to A. fumigatus virulence. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the virulence of the ΔcalA mutant in an immunosuppressed mouse model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. We found that mice infected with the ΔcalA mutant had significantly longer survival than mice infected with either the wild-type or ΔcalA+calA complemented strains (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, after 5 days of infection, the pulmonary fungal burden of mice infected with the ΔcalA mutant was significantly lower, as determined by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that CalA is required for maximal virulence during invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

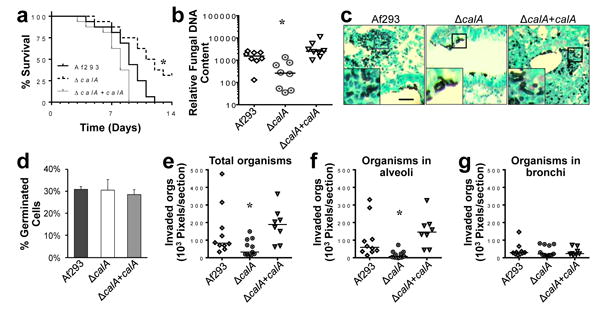

Figure 5. CalA is required for normal virulence and lung invasion in the mouse model of invasive aspergillosis.

a, Survival of mice that were immunosuppressed with cortisone acetate and then infected with the indicated strains of A. fumigatus. Data are the combined results of two independent experiments for a total 16 mice per strain. *P < 0.01 compared to Af293 and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (Log-rank test). b, Pulmonary fungal burden of mice after 5 d of infection with the indicated strains. Results are from 8 mice per strain. Horizontal bars indicate the median values. *P < 0.02 compared to Af293 and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (Wilcoxon rank sum test). c, Photomicrographs of Gomori-methenamine silver stained sections of the lungs of mice 12 h after intratracheal inoculation with 107 conidia of the indicated strains. Insets show magnified images of the regions outlined by the square boxes. Scale bar, 20 μm. d, Germination of the indicated A. fumigatus strains in vivo. Results are the mean ± SD of 3 mice infected with each strain, analyzing 154, 133 and 152 cells in the thin sections of the lungs from the 3 mice infected with Af293, 143, 112, and 158 cells from the mice infected with the ΔcalA mutant strain, and 156, 176, and 159 cells from mice infected with the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain. e-g, Quantitative analysis of invasion into all lung tissues (e), the alveoli (f), and the bronchi (g) by the indicated A. fumigatus strains 12 h after intratracheal inoculation. Results are from a total of 10 lung sections from 3 mice infected with Af293, 11 sections from 3 mice infected with the ΔcalA mutant, and 8 sections from 2 mince infected with the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain. Horizontal line indicates the median. *P < 0.04 compared to Af293 and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

In some, but not all A. fumigatus mutants, delayed germination has been associated attenuated virulence25,26. Therefore, we investigated the capacity of the ΔcalA mutant to germinate in vivo by quantitative image analysis of thin sections of the infected lungs. We found that all three strains germinated similarly in the lungs of the infected mice (Fig. 5c, d), indicating that CalA is dispensable for germination in vivo. Of note, the percentage of organisms that had germinated after 12 h of infection in mice was similar to percentage of organisms that had germinated after only 6 h in vitro (Figs. 5c,d and 2a). Thus, A. fumigatus germinates significantly more slowly in vivo than in vitro.

To verify that the ΔcalA mutant was defective in tissue invasion in vivo, we imaged the thin sections of the lungs and quantitatively analyzed the foci of infection for the presence and location of invasive fungal cells. Significantly fewer cells of the ΔcalA mutant were found to have invaded into the lung tissue as compared to the wild-type and ΔcalA+calA complemented strains (Fig. 5c, e). Moreover, the limited number of cells of the ΔcalA mutant that had invaded were located mainly in the bronchi rather than the alveoli (Fig. 5c, f, g). By contrast, the majority of the invasive cells of the wild-type and ΔcalA+calA complemented strain were located in the alveoli and relatively few were located in the bronchi. Taken together, the in vitro and in vivo data strongly suggest that the virulence defect of ΔcalA mutant was due to impaired host cell invasion.

Next, we investigated the possibility that Cal influenced the host inflammatory response to A. fumigatus. Thin sections of the lungs of mice infected with the wild-type and ΔcalA+calA complemented strain had multiple foci of infection, as determined by histopathology. In these foci, the hyphal elements were surrounded by numerous neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 11). While the lungs of the mice infected with the ΔcalA mutant contained much fewer fungal lesions, the neutrophilic infiltrate around these lesions was similar to what was observed in mice infected with the wild-type strain. To further study the inflammatory response induced by the ΔcalA mutant, we analyzed the production of proinflammatory cytokines by endothelial cells that had been infected with the various A. fumigatus strains for 16 h. We found that endothelial cells infected with the ΔcalA mutant secreted similar levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8, and MCP-1 as did cells infected with the wild-type strain (Supplementary Fig. 12). These results suggest that CalA does not influence the host inflammatory response to A. fumigatus, except by decreasing the lung fungal burden due to reduced invasion of the lung parenchyma.

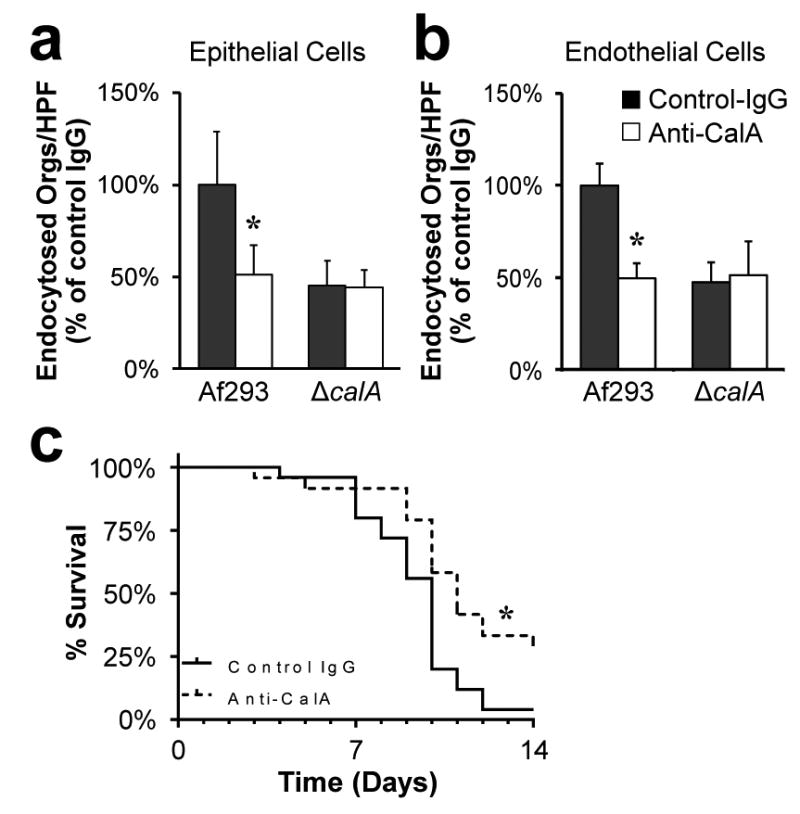

An Anti-CalA antibody prolongs survival

Because CalA is a cell surface protein that is required for pathogenicity, it is a potential target for passive immunotherapy against invasive aspergillosis. To test this hypothesis, a polyclonal rabbit antibody was raised against a peptide that encompassed a predicted cell surface domain of CalA. First, we confirmed that the anti-CalA antibody blocked the endocytosis of wild-type A. fumigatus by both A549 epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 6a, b). This antibody had no effect on the endocytosis of the ΔcalA mutant and it did not inhibit A. fumigatus germination. Next, we monitored the survival of mice that had been given either a single dose of control rabbit IgG or the anti-CalA antibody prior to infection with A. fumigatus. We found that mice treated with the anti-CalA antibody had significantly increased survival compared to the mice that received control IgG (Fig. 6c). These data indicate that inhibition of CalA reduces A. fumigatus virulence and suggest that CalA is a potential immunotherapeutic target for preventing invasive aspergillosis.

Figure 6. An anti-CalA antibody inhibits host cell invasion and protects mice from lethal invasive aspergillosis.

a and b, Effect of the anti-CalA antibody on the endocytosis of A. fumigatus Af293 and the ΔcalA mutant by A549 epithelial cells (a) and vascular endothelial cells (b). Results are mean ± SD of 3 experiments, each performed in triplicate *P < 0.001 compared to Af293 incubated with the control IgG (two-tailed Student's t-test assuming unequal variances). HPF, high-powered field. c, Survival of mice that were immunosuppressed with cortisone acetate and then infected with the indicated strains of A. fumigatus. Data are the combined results of three independent experiments for a total 24 mice per treatment group. *P < 0.01 compared to Af293 and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strain (Log-rank test).

Discussion

A. fumigatus CalA is predicted to be a member of the thaumatin-like protein superfamily27. This diverse group of proteins is present in some Ascomycete and Basidiomycete fungi, as well as in plants, nematodes, and insects27,28. Some thaumatin-like proteins have a sweet taste because they bind to G protein-coupled receptors in the taste buds29. The data presented herein indicate that A. fumigatus CalA functions as an invasin by binding to a different host receptor, integrin α5β1, thereby inducing host cell endocytosis of adherent organisms. Although our data strongly indicate that the interaction of CalA with integrin α5β1 mediates the endocytosis of A. fumigatus, there must be additional A. fumigatus invasins because deletion of calA did not completely block host cell invasion. Moreover, the finding that the ΔcalA mutant invaded the integrin β1-deficient GD25 cell line less efficiently than the wild-type strain suggests that CalA binds to an additional host cell receptor(s). The presence of multiple invasins and receptors in a single organism is not unexpected; for example, the fungus C. albicans has at least two invasins that interact with multiple host cell receptors13,30,31.

The ΔcalA mutant had significantly attenuated virulence in corticosteroid-treated mice, as demonstrated by improved survival, reduced lung fungal burden, and decreased lung tissue invasion in animals infected with this mutant. These results indicate that CalA mediates pulmonary invasion, and that invasion of host cells plays a key role in the pathogenesis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. CalA may play an especially prominent role in pathogenicity during infection in the presence of corticosteroids, which enhance expression of integrin α5 by some host cells32. Proteins such as CalA that are expressed on the fungal cell surface are promising therapeutic targets because of their accessibility. For example, a vaccine composed of the recombinant N-terminal portion of the C. albicans Als3 invasin is currently in clinical trials33. Here, we found that a single dose of the anti-CalA antibody provided partial protection against invasive aspergillosis. These results support the ongoing investigation of CalA as a potential target for passive immunotherapy against invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

All A. fumigatus strains (listed in Supplementary Table S1) were grown on Sabauroud dextrose agar at 37°C for 7 d. Conidia were harvested by rinsing the colonies with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 80, collected by centrifugation, and enumerated with a hemacytometer. Swollen conidia were prepared by incubating resting conidia in F-12K medium at 37°C for 4 h. Germlings were prepared by incubating conidia in petri dishes containing Sabauroud dextrose broth at 37°C for 4 h and then at 4°C overnight. The next day, the dishes were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h, after which the germlings were rinsed, scraped from the plate, and counted. Under these conditions, the ΔcalA mutant germinated similarly to the wild-type strain.

Strain construction

All A. fumigatus mutants were constructed using strain Af293. A split marker strategy was used to disrupt the 534 bp calA (Afu3g09690) protein coding sequence34. Two DNA fragments, one encompassing 1,502 bp upstream of calA and one encompassing 1,529 bp downstream of calA were amplified from genomic DNA of A. fumigatus strain Af293 by high-fidelity PCR using primers CalA-P1, CalA-P2 and CalA-P3, CalA-P4 (Supplementary Table S2). Each fragment was cloned into the entry vector pENTR™/D-TOPO (Invitrogen). Subsequently, LR clonase reactions were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions to introduce the upstream and downstream flanking fragments into the pHY-Pr-att and pYG-Tr-att vectors to yield pCalA-HY and pCalA-YG, respectively 35. Next, a DNA fragment containing the upstream calA flanking region and the 5′ portion of the hygromycin resistance cassette was amplified by high-fidelity PCR from pCalA-HY using primers CalA-P1 and HY. Similarly, a DNA fragment containing the downstream calA flanking region and the 3′ portion of the hygromycin resistance cassette was amplified from pCalA-YG using primers CalA-P4 and YG. A. fumigatus was transformed with both fragments by protoplasting. Hygromycin-resistant clones were screened for disruption of calA by colony PCR using primers CalA-RT-F and CalA-RT-R.

To complement the ΔcalA mutant, the intact calA open reading frame, including 2004 bp of upstream sequence and 613 bp of downstream sequence, was amplified from genomic DNA by high-fidelity PCR using primers CalA-Com-F and CalA-Com-R. After NotI digestion, the resulting fragment was cloned into plasmid p402, which contains the phleomycin resistance gene36. The resulting plasmid was transformed into the ΔcalA mutant. Hygromycin- and phleomycin-resistant clones were selected and the integration of intact wild type allele calA was detected by whole cell PCR using primers CalA-Com-F and CalA-Com-R.

To construct a mutant of A. fumigatus that expressed CalA with RFP linked to its C-terminus, a 2534 bp DNA fragment containing 2003 bp of the calA promoter region and the 531 bp open reading frame was amplified with primers CalA-RFP-F and CalA-RFP-R. Next, the fragment was cloned into the RFP-Phleo plasmid at the SacI-EcoRV sites37. The resulting plasmid, pcalA-RFP, was subsequently transformed into Af293, and the integration of the plasmid was confirmed by whole cell PCR using primers CalA-RFP-F and CalA-RFP-R.

To generate a strain of S. cerevisiae that expressed calA-RFP, the calA-RFP fusion DNA fragment was amplified from plasmid pcalA-RFP by high-fidelity PCR with primers sCalA-RFP-F and sCalA-RFP-R (Supplementary Table S2). This fragment was cloned into pESC-LEU (Agilent Technologies) at the SpeI-SacI sites. The resulting plasmid and the backbone pESC-LEU vector were used to transform S. cerevisiae S150-2B to obtain the CalA-S and pESC-S strains. Next, these two strains were transformed with plasmid pYF-5, which contained the C. albicans ALS1 adhesin gene14. Control strains of S. cerevisiae were transformed with the backbone pESC-LEU vector alone. All S. cerevisiae strains were cultured in SC medium at 30oC. Expression of calA-RFP was induced by growth in SC medium containing 2% galactose and 1% raffinose overnight.

To construct GFP-expressing strains of A fumigatus for the invasion assays, the wild-type strains and the ΔcalA mutant were transformed with a GFP expression plasmid that contained the ble phleomycin resistance marker (GFP-Phleo) 37,38. The ΔcalA+calA complemented strain was transformed with a GFP expression plasmid with pyrithiamine resistance marker (GFP-pPTRI), which was constructed by insertion of the eGFP gene into the PstI/SmaI site of pPTRI (Takara Bio Inc).

Cell culture

The A549 type II pneumocyte cell line (American Type Culture Collection) was grown as described39. Endothelial cells were isolated from human umbilical cord veins and grown as described6. The GD25 and β1AGD25 cell lines were from Dr. Deane F. Mosher, University of Wisconsin-Madison18. Primary human pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells (HPAEpiC) were purchased and cultured as recommended by the supplier (ScienceCell Research Laboratories). All cells and cell lines were free of mycoplasma contamination. The A549 cell line was authenticated by the American Type Culture Collection, and the GD25 and β1AGD25 cell lines were authenticated by immunoblotting to detect the absence and presence of integrin β1, respectively.

Production of the anti-CalA antibody

The anti-CalA polyclonal antibody was produced commercially (ProMab Biotechnologies, Inc.) by immunizing rabbits with the CalA-derived peptide DQSDVLQFEYTQSGDTIC and then isolating CalA-specific IgG.

Detection of surface expressed CalA using the Anti-calA antibody

Germlings of the various A. fumigatus strains were incubated with the anti-calA antibody (20 μg/ml), rinsed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then incubated with AlexaFluor 568-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The organisms were imaged by confocal microscopy. In a separate experiment, the binding of the anti-CalA antibody to the different A. fumigatus strains was analyzed by flow cytometry as described40.

Adherence assay

The capacity of the fungal strains to adhere to A549 cells and solid phase laminin was determined by colony counting as previously described41. To determine adherence to fluid-phase laminin, 1 mg laminin (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc) was dialyzed overnight at 4°C under constant shaking and then labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) following the manufacture's protocol. The protein content of the labeled protein was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay. Next, 107 swollen conidia were incubated with 50 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 488-laminin or PBS at 37°C for 1 h in a shaking incubator. Afterwards, the organisms were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The fluorescent intensity of the organisms was quantified by flow cytometry, collecting fluorescence data for 10,000 cells of each strain.

Galactosaminogalactan quantification

To quantify galactosaminogalactan production by the various strains, culture filtrate from 72 h culture was ethanol precipitated and processed as previously described12,42.

Invasion assay

The endocytosis of A. fumigatus by host cells was determined using a minor modification of our standard differential fluorescence assay13. Briefly, host cells were cultured on fibronectin-coated coverslips and infected with 105 germlings of the various GFP expressing A. fumigatus strains. After incubation for 2.5 hours, the cells were rinsed with HBSS, and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. The noninternalized organisms were stained with a rabbit anti-A. fumigatus antibody (Meridian Life Science, Inc.) followed by an AlexaFluor 568-labeled secondary antibody (Life Technologies)6. The coverslips were mounted inverted and observed under epifluorescence. The number of endocytosed organisms was determined by subtracting the number of noninternalized organism from the total number of organisms, counting at least 100 organisms per coverslip. The uptake of S. cerevisiae strains by endothelial cells was also determined by a differential fluorescence assay as previously described13.

Susceptibility to stressors

Serial 10-fold dilutions of conidia of the different A. fumigatus strains ranging from 105 to 102 cells in 5 μl PBS were spotted onto Sabauroud agar plates containing 300 μg/ml Congo red (Sigma-Aldrich), 300 μg/ml calcofluor white (Sigma-Aldrich), 40 μg/ml caspofungin (Merck), 0.01% SDS (Life Technologies), or 2 mg/ml protamine (Sigma-Aldrich). Fungal growth was analyzed after incubation at 37°C for 2 days.

Phagocyte killing of A. fumigatus

HL-60 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were differentiated into macrophage-like and neutrophil-like cells as previously described43,44. The susceptibility of swollen conidia of the various strains to killing both cell types was measured at a target to effector cell ratio of 1:50 and an incubation time of 2.5 h by our previously described method43.

Germination assay

Conidia from GFP labeled strains in F-12K medium were added to confluent A549 cells and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. At various time points, the medium was aspirated and the cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The wells were examined by epifluorescence microscopy, and the number of organisms producing a germ tube at least 1 conidial diameter in length was determined. At least 100 organisms were counted on each coverslip.

Scanning electron microscopy

For electronic microscopy, 5 × 105 conidia/ml of Af293, ΔcalA and the ΔcalA+calA complemented strains were pre-germinated in RPMI 1640 medium at 37°C for 18 h. Next, the hyphae were harvested and incubated for 6 h on A549 cells on glass coverslips, and then rinsed in PBS and fixed overnight with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C. Subsequently, the samples were dehydrated and critical-point dried. Finally, the coverslips were sputter coated with Au-Pd and imaged with a Hitachi S-3000 N scanning electron microscope.

Isolation and identification of host cell proteins that bind to A. fumigatus

Host cell membrane proteins that bound to A. fumigatus were isolated and affinity-purified as outlined previously45. Briefly, cell surface proteins were labeled with Ez-Link Sulfo-NHS-LS Biotin (Pierce), extracted with octyl-glucopyranoside, and incubated with A. fumigatus germlings. Host cell proteins that bound to the fungus were eluted with 6 M urea, separated by SDS-PAGE, and detected by immunoblotting with an anti-biotin antibody. The prominent bands were excised and the proteins within them were identified by NanoLC-MS/MS (UCLA Molecular Instrumentation Center). The binding of integrin α5β1 to A. fumigatus strains was analyzed by probing immunoblots of the eluted host cell membrane proteins with antibodies against integrin α5 (ab150361; Abcam) and β1 (ab52971; Abcam).

Confocal microscopy

The accumulation of integrin α5β1 around A. fumigatus was visualized as previously described13. Briefly, epithelial or endothelial cells were infected with 105 A. fumigatus germlings. After 2.5 h, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked with 5% goat serum, and sequentially incubated with antibodies against integrin β1 or integrin α5 (CBL497, EMD Millipore), followed by the appropriate secondary antibodies labeled with either Alexa Fluor 568 or Alexa Fluor 488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The host cells were imaged by confocal microscopy and the fungi were visualized by DIC imaging.

To detect the binding of recombinant integrin α5β1 to S. cerevisiae expressing CalA and calA, the cells were allowed to adhere to glass coverslips and then incubated with 10 μg/ml recombinant integrin α5β1 (R&D systems) in PBS for 1 h. The cells were then washed and incubated with anti-integrin α5 antibody (CBL497, EMD Millipore). They were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by incubation with an Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG antibody. The coverslips were mounted inverted on a microscope slide and imaged by confocal microscopy.

Antibody blocking, siRNA, and inhibitors

For antibody blocking experiments, host cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL of the anti-β1 integrin antibody (6S6, Millipore), 25 μg/mL of the anti-α5 integrin antibody (NKI-SAM-1, Millipore), or 25 μg/ml control mouse IgG for 45 min before infection. To knock down integrins, host cells were transfected with integrin β1 siRNA (sc-35674; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), integrin α5 siRNA (sc-29372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), α3 integrin siRNA (sc-35684; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or random control siRNA (Qiagen) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The efficiency of siRNA knockdown was verified by immunoblotting of whole cell lysates with the anti-β1, anti-α5, and anti-α3 (MAB1952Z, EMD Millipore) antibodies. For cytochalasin D studies, the host cells were incubated with 0.4 μM cytochalasin D in 0.1% DMSO for 45 min prior to infection with A. fumigatus in medium containing the same concentration of cytochalasin D. Control wells were incubated with 0.1% DMSO alone. The peptide inhibitions studies used the peptide GRGDSP to block the fibrinogen binding site of integrin α5β146 and Ac-PHSCN-NH2 (ATN-161; MedKoo Biosciences Inc.) to block the fibrinogen synergy site23. Both peptides were used at a concentration of 50 μM. They were added to the cells 45 min prior to infection and remained in the medium for the duration of the experiment.

Mouse model of invasive aspergillosis

The virulence of the A. fumigatus strains was assessed in our standard mouse model of invasive aspergillosis as described43,47. Briefly, 6 week male Balb/C mice (Taconic Laboratories) were immunosuppressed with cortisone acetate and then 11 mice were randomized for infection by each strain. The mice were infected by placing them in a chamber into which 1.2×1010 conidia were aerosolized. Controls mice were immunosuppressed, but were not infected. Shortly after infection, 3 mice from each group were randomly selected, sacrificed, and their lungs were harvested, homogenized, and quantitatively cultured to verify conidia delivery to the lung, which was determined to be approximately 4,000 conidia per mouse for each strain. The remaining mice were monitored for survival by an unblinded observer. The survival experiments were repeated twice and the results were combined for a total of 16 mice per strain, providing 80% power to detect a 1-d difference in median survival by the Log-rank test. All animals were included in the analysis.

To determine pulmonary fungal burden, immunosuppressed mice were infected with A. fumigatus as above (n=8 mice per strain, providing 80% power to detect a 0.5-log difference in median fungal burden by the Wilcoxon rank sum test). After 5 d of infection, the mice were sacrificed and their lung were harvested and homogenized in lysis solution (ZR Fungal/Bacterial DNA MiniPrep™, Epigenetics) using a gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). The homogenates were processed following the manufacturer's directions to isolate fungal DNA. The relative fungal DNA content was quantified by real-time PCR with primers ASF1 and ADR1 (Supplementary Table S1)48 using the 2-ΔΔCT method with mouse GAPDH as the reference gene.

The extent of germination of A. fumigatus strains was analyzed using 3 mice per strain. Mice were immunosuppressed as above, anesthetized with xylazine and ketamine, and inoculated with 107 conidia by intratracheal injection. After 12 h, mice were sacrificed, and the lungs were harvested and processed for histochemical analysis with Gomori methenamine silver staining to visualize the organisms. The slides were viewed by light microscopy and the percentage of germinated conidia was determined by analyzing at least 200 cells per strain.

To quantify the extent of lung tissue invasion, all foci of infection in each thin section were imaged under the same magnification. Using ImageJ, the area of fungi that had invaded into the alveoli and bronchi of the lung tissue was quantified for each lung section.

Anti-CalA antibody studies

The effects of the anti-CalA antibody or control rabbit IgG on host cell endocytosis of A. fumigatus was determined using an antibody concentration of 10 μg/ml. For survival studies, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.1 mg of the anti-CalA antibody or control rabbit IgG 2 h before infection. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute and performed according to the National Institute of Health guidelines for animal housing and care.

Cytokine production

To measure the production of cytokines induced by the various A. fumigatus strains, 5×105 germlings in 0.5 ml of medium were added to confluent endothelial cells in a 24-well plate. After 16 h infection, the supernatant was collected, clarified by centrifugation, and stored in aliquots at -80°C. The concentration of MCP-1/CCL2, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-8 in the medium was determined using the Luminex multipex assay (R&D Systems). Each strain was tested in 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Villarreal for assistance with tissue culture. This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI073829 and R56AI111836, by UCLA CTSI Grant UL1TR000124, and by operating grants 81361 and 123306 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. A.S.I is supported by NIH grant R01AI063503. D.C.S is supported by a Chercheur-Boursier Award from the Fonds de Recherche Quebec Santé (FRQS).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: HL, ML, NS, QP, AI, DS, and SF designed the experiments, HL ML, NS, QP, MS, BR performed the experiments, HL, ML, DS, and SF analyzed the data, HL, DS, and SF wrote the paper.

Competing Financial Interests: AI and SF are co-founders of and hold equity in NovaDigm Therapeutics, Inc.

References

- 1.Maschmeyer G, Haas A, Cornely OA. Invasive aspergillosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and management in immunocompromised patients. Drugs. 2007;67:1567–1601. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taccone FS, et al. Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: clinical presentation, underlying conditions, and outcomes. Crit Care. 2015;19:7. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filler SG, Sheppard DC. Fungal invasion of normally non-phagocytic host cells. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e129. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeHart DJ, Agwu DE, Julian NC, Washburn RG. Binding and germination of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia on cultured A549 pneumocytes. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:146–150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamai Y, Lossinsky AS, Liu H, Sheppard DC, Filler SG. Polarized response of endothelial cells to invasion by Aspergillus fumigatus. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:170–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopes-Bezerra LM, Filler SG. Interactions of Aspergillus fumigatus with endothelial cells: internalization, injury, and stimulation of tissue factor activity. Blood. 2004;103:2143–2149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paris S, et al. Internalization of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by epithelial and endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1510–1514. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1510-1514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasylnka JA, Moore MM. Uptake of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells in vitro: quantitation using strains expressing green fluorescent protein. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3156–3163. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3156-3163.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasylnka JA, Moore MM. Aspergillus fumigatus conidia survive and germinate in acidic organelles of A549 epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1579–1587. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheppard DC, Filler SG. Host cell invasion by medically important fungi. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Upadhyay SK, et al. Identification and characterization of a laminin-binding protein of Aspergillus fumigatus: extracellular thaumatin domain protein (AfCalAp) J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:714–722. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.005991-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gravelat FN, et al. Aspergillus galactosaminogalactan mediates adherence to host constituents and conceals hyphal β-glucan from the immune system. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003575. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phan QT, et al. Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu Y, et al. Expression of the Candida albicans gene ALS1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae induces adherence to endothelial and epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1783–1786. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1783-1786.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheppard DC, et al. Functional and structural diversity in the Als protein family of Candida albicans. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30840–30849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belaish R, et al. The Aspergillus nidulans cetA and calA genes are involved in conidial germination and cell wall morphogenesis. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008;45:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu W, et al. EGFR and HER2 receptor kinase signaling mediate epithelial cell invasion by Candida albicans during oropharyngeal infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14194–14199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117676109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wennerberg K, et al. Beta 1 integrin-dependent and -independent polymerization of fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:227–238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemler ME, Huang C, Schwarz L. The VLA protein family. Characterization of five distinct cell surface heterodimers each with a common 130,000 molecular weight beta subunit. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3300–3309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secott TE, Lin TL, Wu CC. Mycobacterium avium subsp paratuberculosis fibronectin attachment protein facilitates M-cell targeting and invasion through a fibronectin bridge with host integrins. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3724–3732. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3724-3732.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha B, et al. Fibronectin-binding protein acts as Staphylococcus aureus invasin via fibronectin bridging to integrin alpha5beta1. Cell Microbiol. 1999;1:101–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cue D, Dombek PE, Lam H, Cleary PP. Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M1 encodes multiple pathways for entry into human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4593–4601. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4593-4601.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livant DL, et al. Anti-invasive, antitumorigenic, and antimetastatic activities of the PHSCN sequence in prostate carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2000;60:309–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isberg RR, Leong JM. Multiple beta 1 chain integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes bacterial penetration into mammalian cells. Cell. 1990;60:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Bader N, et al. Role of trehalose biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus development, stress response, and virulence. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3007–3018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00813-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hohl TM, Feldmesser M. Aspergillus fumigatus: principles of pathogenesis and host defense. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1953–1963. doi: 10.1128/EC.00274-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu JJ, Sturrock R, Ekramoddoullah AK. The superfamily of thaumatin-like proteins: its origin, evolution, and expression towards biological function. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29:419–436. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0826-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenstein S, et al. Analysis of the Aspergillus nidulans thaumatin-like cetA gene and evidence for transcriptional repression of pyr4 expression in the cetA-disrupted strain. Fungal Genet Biol. 2006;43:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda T, et al. Five amino acid residues in cysteine-rich domain of human T1R3 were involved in the response for sweet-tasting protein, thaumatin. Biochimie. 2013;95:1502–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun JN, et al. Host cell invasion and virulence mediated by Candida albicans Ssa1. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001181. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Mittal R, Solis NV, Prasadarao NV, Filler SG. Mechanisms of Candida albicans trafficking to the brain. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002305. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowin T, et al. Glucocorticoids increase alpha5 integrin expression and adhesion of synovial fibroblasts but inhibit ERK signaling, migration, and cartilage invasion. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3623–3632. doi: 10.1002/art.24985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt CS, et al. NDV-3, a recombinant alum-adjuvanted vaccine for Candida and Staphylococcus aureus, is safe and immunogenic in healthy adults. Vaccine. 2012;30:7594–7600. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catlett NL, Lee BN, Yoder OC, Turgeon BG. Split-marker recombination for efficient targeted deletion of fungal genes. Fungal Genet News. 2002;50:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gravelat FN, Askew DS, Sheppard DC. Targeted gene deletion in Aspergillus fumigatus using the hygromycin-resistance split-marker approach. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;845:119–130. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-539-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richie DL, et al. The Aspergillus fumigatus metacaspases CasA and CasB facilitate growth under conditions of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:591–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee MJ, et al. Overlapping and distinct roles of Aspergillus fumigatus UDP-glucose 4-epimerases in galactose metabolism and the synthesis of galactose-containing cell wall polysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:1243–1256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.522516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campoli P, et al. Concentration of antifungal agents within host cell membranes: a new paradigm governing the efficacy of prophylaxis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5732–5739. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00637-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pongpom M, et al. Divergent targets of Aspergillus fumigatus AcuK and AcuM transcription factors during growth in vitro versus invasive disease. Infect Immun. 2015;83:923–933. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02685-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouchara JP, et al. Sialic acid-dependent recognition of laminin and fibrinogen by Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2717–2724. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2717-2724.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gravelat FN, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus MedA governs adherence, host cell interactions and virulence. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:473–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fontaine T, et al. Galactosaminogalactan, a new immunosuppressive polysaccharide of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002372. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus AcuM regulates both iron acquisition and gluconeogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:1038–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins SJ. The HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cell line: proliferation, differentiation, and cellular oncogene expression. Blood. 1987;70:1233–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phan QT, Fratti RA, Prasadarao NV, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG. N-cadherin mediates endocytosis of Candida albicans by endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10455–10461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Nhieu GT, Isberg RR. The Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin protein and human fibronectin bind to mutually exclusive sites on the alpha 5 beta 1 integrin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24367–24375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ejzykowicz DE, et al. The Aspergillus fumigatus transcription factor Ace2 governs pigment production, conidiation and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:155–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williamson EC, et al. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in bone marrow transplant recipients by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:132–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.