Abstract

Formation of polarized epithelial tubules is a hallmark of kidney development. One of the fundamental principles in tubulogenesis is that epithelia coordinate the polarity of individual cells with the surrounding cells and matrix. A central feature in this process is the segregation of membranes into spatially and functionally distinct apical and basolateral domains, and the generation of a luminal space at the apical surface. This review will examine our current understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie the establishment of apical-basal polarity and lumen formation in developing renal epithelia, including the roles of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions and polarity complexes. We will highlight growing evidence from animal models, and correlate these findings with models of tubulogenesis from other organs systems, as well as from in vitro studies.

Keywords: Kidney development, tubulogenesis, lumen, apical-basal polarity, afadin, nephron, cadherin, cap mesenchyme, renal vesicle

Introduction

The formation of polarized epithelial tubules is central to the structure and function of many organs, including the kidney [1, 2]. Defects in epithelial tubule organization and polarization are a feature of several inherited renal diseases, including the renal cystic diseases, the most prominent of which is autosomal dominant polycystic disease [2]. Disruption of epithelial integrity and morphogenesis is also characteristic of certain nephronophthises, a group of rare genetic renal disorders of children characterized by small cysts and interstitial fibrosis [3, 4]. Additionally, overt defects in apical-basal polarity are present in acquired diseases such as acute kidney injury and cancer [5, 6]. For these compelling reasons, it is imperative to advance our understanding of the mechanisms that govern tubulogenesis and polarization.

Central to epithelial tubulogenesis is the development of spatially and functionally distinct plasma membrane surfaces. Epithelial cells can polarize along two axes, apical-basal and planar polarized, and this review will focus specifically on mechanisms of apical-basal polarity and how they regulate tubular morphogenesis. In renal epithelial tubules, a polarized monolayer surrounds a central lumen. The apical plasma membrane faces the centrally located lumen, the lateral plasma membrane contacts adjacent cells, and the basal plasma membrane contacts the underlying extracellular matrix. Typically within the literature, the basal and lateral membranes are collectively referred to as basolateral membranes. However, it is worth noting that there are features and proteins that are specific to either lateral or basal membranes, such as the laterally located NCAM in developing nephron tubules. Nonetheless, for simplicity we will use the basolateral nomenclature here.

Within each cell, multiple cellular processes must be coordinated to cause the asymmetric distribution of membrane surfaces and maintain their segregation after development. The formation of polarity complexes and polarized vesicular transport are key elements in generating and maintaining this asymmetry. Importantly, however, the apical-basal asymmetry of each cell must be synchronized with that of neighboring cells in order to form a tubule. This coordination occurs largely through signals from cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions that orient the cells to their environment.

Once apical-basal asymmetry has developed, a luminal space is created, which may be expanded or elongated. These processes can be highly dynamic, as tubulogenesis is accompanied by morphogenetic movements and cellular proliferation. In this review, we discuss the different mechanisms by which tissues undergo tubulogenesis, focusing on lumen formation. We summarize our understanding of the stages of nephron tubulogenesis, namely, apical-basal polarization and lumen initiation, lumen expansion, and finally, lumen elongation.

Biological diversity of tubules

Tubules are one of the most common tissue types in metazoan biology. Therefore, it is of little surprise that there is significant diversity in tubular anatomy. The reader is referred to several excellent reviews that have addressed this in great detail [7–9]. Some tubules contain lumens enclosed by a single cell, while others are comprised of multiple cells that “seal” the lumens by auto- or intercellular junctions. The former is less common, and the prototypic example is the Drosophila tracheal system [10], although the C. elegans excretory cell [11] and a subset of endothelial tubules also have this structure [12]. In fact, the majority of tubules contain multicellular lumens, including the epithelial tubules of the kidney, pancreas, and mammary gland. Additional organizational diversity exists in that tubules may be branched and/or may terminate with a cap-like structure, such as acini (e.g. pancreas and mammary gland) or alveoli (e.g. lung). Even the position of the lumen is variable, with hepatocytes positioning their lumen perpendicular to the basal surface of the cell [13, 14]. Despite these differences, a shared feature among these tubules is a single, enclosed lumen.

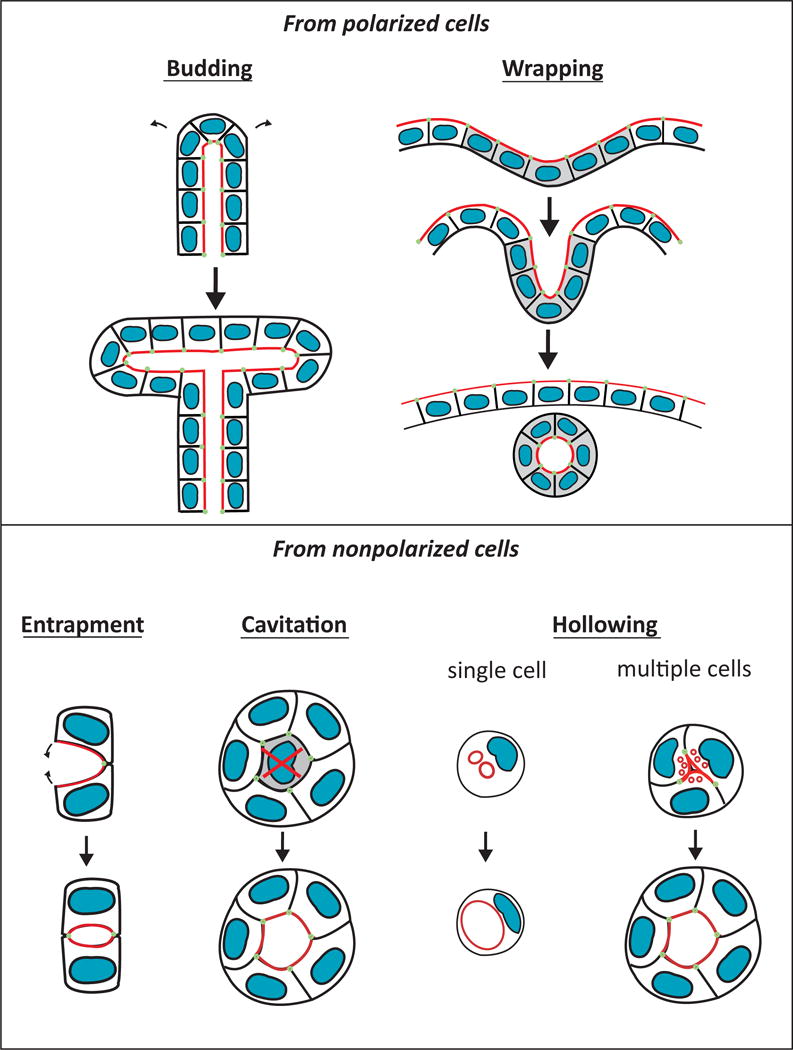

The formation of a single lumen can occur by several different cellular processes, including budding, wrapping, entrapment, cavitation, and hollowing (Figure 1). In general, the formation of tubules by budding or wrapping starts with a fully polarized epithelium. In contrast, the formation of tubules by entrapment, cavitation, or hollowing is initiated by non-polarized cell(s). Entrapment occurs when migrating cells enclose or “entrap” extracellular space to form a lumen, as occurs in Drosophila heart formation [15, 16]. Cavitation is a model of lumen formation (e.g. in mammary epithelia, salivary gland) in which the clearance of an inner cell population through apoptosis creates a luminal space [17]. Hollowing is a mechanism of lumen formation that occurs when a luminal space is generated de novo within a single cell or a cord of cells through the exocytosis of intracellular vesicles [8]. The molecular mechanisms regulating these processes are tissue and cell type specific.

Figure 1.

Diverse cellular mechanisms of lumen formation. Mechanisms of budding, wrapping, entrapment, cavitation and hollowing are illustrated. The apical surface (red) and apical cell-cell junctions (green) are shown.

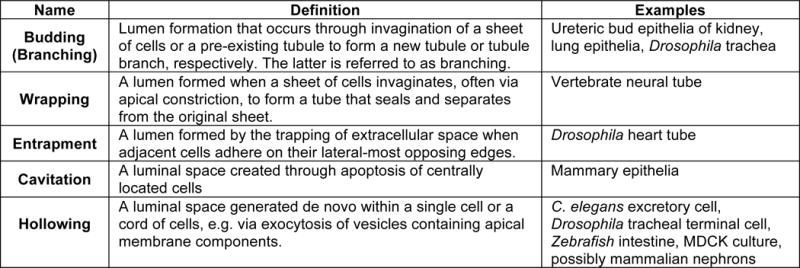

A great deal of our knowledge of mechanisms that underlie the spatial and temporal regulation of renal tubulogenesis is inferred from cultured cells, of which Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells are the most well-studied. MDCK cells cultured as a monolayer (called two-dimensional culture), in which cells are plated on a culture dish or in a transwell, have been used to study apical-basal polarization and identify protein complexes that define the apical and basolateral surfaces. Three-dimensional (3D) MDCK cultures are generated by plating dissociated cells into a gel of matrix components; each individual cell proliferates to form a 3D polarized vesicle of epithelial cells surrounding a fluid-filled lumen, termed a cyst. The study of these cultures has provided a good model for tubulogenesis, allowing study of polarization as well as lumen formation and opening. MDCK cells are thought to derive from cells of the distal nephron [18], suggesting this model may most closely approximate nephron tubulogenesis. Nonetheless, MDCK cells have been used to successfully study other types of renal tubulogenesis, including ureteric branching morphogenesis [19, 20]. In addition to the cellular mechanisms, the study of MDCK cells has generated a wealth of information on the molecular players involved in generating and maintaining polarized epithelia. Some of the protein complexes involved are depicted schematically in Figure 3 and will be discussed below.

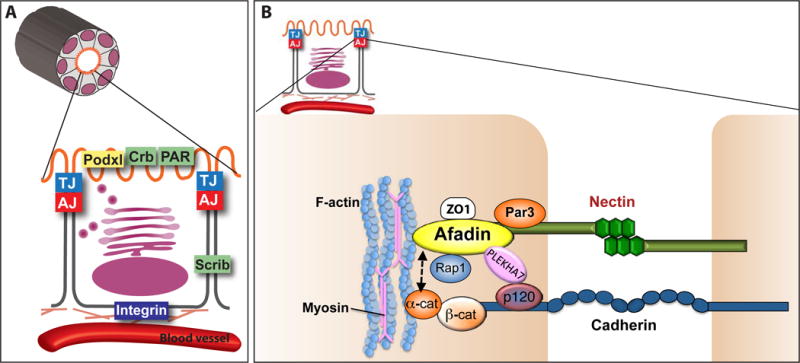

Figure 3. Apical basal polarity in an epithelial cell.

(A) Several complexes confer apical basal polarity in epithelia. (a) Integrin complexes generate cell-matrix adhesion and provide spatial cues. (b) Polarity complexes define the apical and basolateral surfaces. The Par complex (Par3, aPKC, Par6, Cdc42) and Crumbs complex (Crb, Pals, PatJ) are apical, and the Scribble complex (Scrib, Dlg, Lgl) is basolateral. The podocalyxin complex (Podxl, Ezrin, NHERF) is also apical. (c) Adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) proteins also establish polarity and maintain the barrier between apical and basolateral. (d) Vesicular trafficking complexes (not shown) also generate and maintain polarity.

(B) Components of an adherens junction are illustrated. Cadherins and nectins are two major transmembrane receptors, signaling through their adaptor proteins, the catenins and afadin respectively. Catenins include α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120 catenin, as shown. Afadin and α-catenin connect the AJ to the actin cytoskeleton. Afadin interacts with many proteins in addition to nectins, including Rap1, ZO1, and Plekha7 [119].

The mechanism of lumen formation in MDCK cysts is specified by extrinsic cues: cells plated in Matrigel (an extract of matrix proteins and growth factors from murine Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm sarcoma) utilize hollowing, while those plated in purified collagen utilize apoptosis for luminal clearing [21]. This difference is thought to be due to differences in the rate of polarization, as cysts plated solely in purified collagen polarize much more slowly than in Matrigel, despite similar rates of cellular proliferation. Slowing polarization of cells plated in Matrigel, as occurs with Cdc42 depletion, leads to luminal clearing by apoptosis. Thus, luminal clearing by apoptosis is viewed as a corrective mechanism during cyst formation.

The hollowing mechanism in MDCK cysts involves apical membrane delivery by directional vesicle trafficking [22, 23]. During lumen initiation, a subset of apical membrane proteins [e.g. Crumbs family member 3a (Crb3a)] are delivered via vesicular transport to a central location between two opposing cells. This apical membrane is expanded with reorganization of some key proteins to apical junctions, followed by luminal opening.

One key difference between in vivo nephron tubulogenesis and cell culture models is that nephrons are derived from mesenchyme, unlike the culture models, and must differentiate and epithelialize concurrent with tubulogenesis. In addition, the environmental cues of the homogeneous culture are dramatically different from those of a developing nephron, which are distinctly asymmetric, with one side contacting the basal lamina of the ureteric epithelium and the other adjacent to vascular and stromal cells. For these reasons, as well as cell type specific differences, in vivo models of tubulogenesis from a variety of organisms are quite distinct from the in vitro models and thus need to be further studied.

Cellular mechanisms of lumen formation in renal epithelia

Much of our understanding of renal epithelial tubulogenesis in vertebrates comes from embryological studies performed by Clifford Grobstein in the second half of the 20th century. Grobstein demonstrated that kidney development relies on reciprocal interactions between the ureteric bud epithelium (UB) and the adjacent mesenchyme, the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) [24, 25]. The MM produces signals that stimulate cells on the dorsal side of the nephric duct to grow outwards towards the MM, thereby forming the UB (embryonic day 10.5 in mice). The nephric duct and the UB are epithelial tubules. The UB invades the MM by embryonic day 11.5, when the ureteric bud tubule begins to undergo dichotomous (and to a lesser extent trichotomous) budding throughout the embryonic period (Figure 2) [26, 27]. UB budding is typically referred to as UB branching. Reciprocally, the UB signals to the MM, stimulating survival and proliferation of the MM, as well as inducing a subset of the MM to form nephrons.

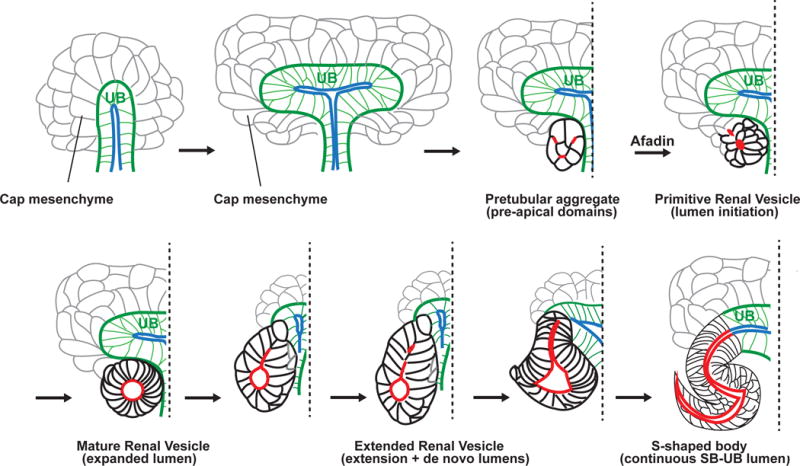

Figure 2.

Nephron tubulogenesis and lumen formation. A subset of the metanephric mesenchyme containing nephron progenitors forms a cap around the ureteric bud (UB) epithelium (green with a blue lumen). This mesenchyme, referred to as the cap mesenchyme (gray), condenses to form pretubular aggregates. In pretubular aggregates, pre-apical domains (red) are present in numerous membranes. Pre-apical domains contain the polarity determinant Par3. These domains reorganize and coalesce in an afadin-dependent manner to form 1–2 small apical foci/lumen in primitive renal vesicles. Pre-apical domain constituents are redistributed to apical lateral cell junctions (not illustrated) as the lumen expands in the mature renal vesicle. Next, the expanded lumen (red) extends toward the ureteric bud lumen (blue) in the extended renal vesicle. Additional separate lumens form in the distal segment. These additional distal lumens eventually coalesce. Finally, the extended lumen joins the ureteric bud lumen at the s-shaped body stage, where a pronounced s-shaped lumen is visible. Various nephron stages are depicted as black with red lumens. Reproduced and modified from Yang et al., 2013.

The metanephric mesenchyme is comprised of nephron progenitors and stromal progenitors. The nephron progenitors surround the ureteric bud tips, forming a “cap” mesenchyme (CM) around them (Figure 2). The progenitor stromal cells interspersed with vascular progenitors surround the cap mesenchyme (not shown). As nephron formation begins, the cap mesenchyme becomes compacted to form a pretubular aggregate (PA) that undergoes a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), forming a sphere of polarized epithelia with a central lumen. This polarized sphere, called the renal vesicle (RV), may arise via hollowing, as there is no pre-existing extracellular space or evidence of apoptosis at the time of lumen formation. Additionally, numerous subapical vesicles have been visualized by transmission electron microscopy [28] and may represent delivery of apical membrane-containing vesicles to the luminal surface. Subsequently, the renal vesicle elongates to form a primordial tubule called the s-shaped body. Each developing s-shaped body will fuse with the tip of an adjacent ureteric bud tubule, thus forming a continuous lumen. The s-shaped body subsequently undergoes extensive morphogenesis to form the majority of the nephron, while the UB gives rise to the collecting duct system. In this regard the kidney is unique: its epithelia form from two distinct cell types (the UB and CM) and through two cellular processes (budding and probably hollowing). Importantly, the lumen from the UB arises from a pre-existing lumen, while the lumen of the nascent nephron arises de novo during MET. These disparate tubule types then undergo a unique process of tubular (and luminal) fusion.

I. Establishing apical basal polarity and lumen initiation in the nephron

In the broadest sense, initiation of tubulogenesis involves the collective orientation of cells within their environment through cell-cell and cell matrix interactions, development of apical-basal polarity, cellular shape changes and movements, and finally, expansion of the luminal space. The cells of the cap mesenchyme are columnar in shape, aligning with their long axis perpendicular to the basal lamina of the ureteric epithelium. Given this alignment and their asymmetric adhesion to the basal lamina, the argument could be made that they are polarized even though they lack an apical surface. However, the timing of apical-basal polarity begins during pretubular aggregation. Recently, it has been shown that pretubular aggregates have small segments, or microdomains, of the plasma membrane that contain Par-3, a member of the apical Par complex [29]. These Par3-containing microdomains at the plasma membrane have a seemingly non-polarized distribution. Interestingly the microdomains exclude basolateral proteins, such as NCAM, suggesting they are small regions of apical surface, or “pre-apical domains”. At the time of renal vesicle initiation, the forming lumen contains Par3 at the apical surface in addition to apical cell junctions. This suggests that the Par3-containing “pre-apical domains” of pretubular aggregates are an early stage of membrane organization preceding overt apical-basal polarity. Their existence implies that the cells of the pretubular aggregates are poised to polarize, prior to decisions on the directionality of polarization.

The pre-apical domains observed during nephron formation are analogous to the pre-apical patch that has been described in vitro (in MDCK cells) in which a forming apical domain lacks basolateral membrane proteins [22, 30]. In these in vitro models, a single pre-apical patch forms between two cells at the site of the future lumen. However, in a pretubular aggregate, there are numerous pre-apical domains. Because only one, or perhaps two, lumens have been observed to arise from a single pretubular aggregate, it suggests that individual pre-apical domains eventually coalesce or reorganize to form a single apical domain across multiple cells. Pre-apical domains might also serve as docking sites for polarized membrane traffic and may define domain boundaries for junction formation.

How pre-apical domains reorganize or traffic to a forming apical surface is not known, yet recent data indicate that progression from pre-apical domains to a coordinated apical surface requires afadin, an F-actin binding protein and adaptor to a major class of adhesion receptors called nectins. Afadin colocalizes with nectins at adherens junctions and tight junctions in fully epithelialized cells. During renal vesicle formation, afadin is essential for the timely initiation of apical basal polarity [29]. Absence of Afadin from developing nephrons in mice leads to reduced consolidation of pre-apical domains and delayed polarization, resulting in delayed lumen formation.

Data is lacking regarding the cellular mechanisms that generate apical-basal polarity and reorganize pre-apical domains in nephrons, so we can only speculate about the possibilities. The first possibility is coalescence of the domains via coordinated endosomal sorting. Several studies that combine mathematical modeling with in vitro experimental data suggest that the generation of apical basal polarity occurs, at least in part, through vesicular membrane sorting. For example, in yeast, cell polarity is established via the spatial coordination of endocytosis and exocytosis [31, 32]. In MDCK cells, vesicular trafficking of apical membrane components, such as podocalyxin, occurs during the formation of the pre-apical patch [30], and a similar process might occur in nephron tubulogenesis. A second possibility is stochastic, lateral diffusion and adhesion (both on the same cell and the opposing cell) of adjacent pre-apical domains. In vitro studies have suggested that the kinetics of membrane diffusion are too slow to solely account for the generation of apical-basal polarity [31]. However, in vivo measurements of membrane diffusion are lacking, and membrane diffusion and adhesion might combine with other mechanisms, such as directed vesicular trafficking and cellular movements, to promote polarity. Live imaging studies will likely be needed to distinguish among these possibilities.

A final consideration is how cell division may play a role in the redistribution of preapical domains and/or apical basal polarization. During the first mitosis event in the formation of MDCK cysts, apical membrane components such as Crb3 and podocalyxin are internalized into endosomal vesicles, partitioned to the spindle poles, and subsequently trafficked along central spindle microtubules to the site of cytokinesis [23]. Near the end of cytokinesis, a transient structure called the midbody forms just prior to the complete separation of the cells. A different subset of apical proteins (e.g. cingulin) forms a ring around the midbody, and once cytokinesis is complete, these proteins are thought to comprise the apical membrane initiation site [33]. These observations suggest two things: first, formation of the apical surface depends upon the proper delivery of apical endosomes, and secondly, the location of the midbody may determine the position of the future apical/luminal surface. The latter has been dubbed “the cytokinesis-landmark model” [34] and implies that factors that determine midbody location may dictate where the apical surface/lumen is placed. In Drosophila follicle cells, loss of cadherin or β-catenin causes mispositioning of the midbody and results in mislocalization of the apical surface in daughter cells once cytokinesis is completed [35]. Whether disruption of the midbody localization per se could lead to multiple lumens in a tubule is not yet certain because loss of individual proteins that disrupt midbody localization also disrupt other aspects of cell division and cell behavior.

Subsequent to the initial lumen formation, the axis of cell division (i.e. the orientation of the mitotic spindle) is important for maintaining the position of the apical surface and expanding the lumen. During metaphase, MDCK epithelia orient their mitotic spindle parallel to the basal lamina and apical surface. Polarity proteins direct the localization of the spindle orientation machinery [36–38]. The loss of one of several polarity proteins, such as members of the Par complex (Par3, aPKC, Par6, and Cdc42), leads to defects in mitotic spindle orientation and misplacement of the apical surface [38–40]. Absence/loss of these proteins in MDCK cysts leads to cysts with multiple lumens, but it is unclear if this is strictly due to disrupted orientation of cell division. Supporting such an idea is that absence/reduction of proteins with specific function in spindle orientation, such as Lgn, also cause a multi-lumen phenotype in MDCK cell cysts [41].

Whether or not these mechanisms are generalizable to in vivo settings, and specifically to nephron tubules, is unknown. One main difference, of course, is that there are a larger number of cells involved in lumen initiation of the early renal vesicle. We do not know if a single or several cells “trigger” the initiation of polarization and whether this is coordinated with cell division. Recent studies indicate that individual cells within a genetically homogeneous population express different numbers of mRNAs and produce different levels of proteins that lead to phenotypic changes [42, 43]. Indeed in the developing kidney, single cell RNA-seq analysis shows stochastic expression of various genes within nephron progenitor cells [44]. Interestingly, only one to few of these individual nephron precursors express Wnt4, a known inducer of epithelialization (see below), supporting a model in which specific cells may trigger the process.

MET and Wnt signaling

During nephrongenesis, the onset of apical-basal polarity is coincident with the conversion of cap mesenchymal cells to epithelial cells, a so-called mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET). The appearance of pre-apical domains occurs at the onset of MET, as pretubular aggregates are forming, suggesting that overlapping signals exist. MET is known to involve the successive activities of Wnt9b and Wnt4. Wnt9b, secreted from the ureteric bud epithelium, can trigger differentiation of the cap mesenchyme [45], in part by inducing expression of Wnt4 in developing pretubular aggregates. Wnt4, then, is both necessary and sufficient to autoinduce its progression to a renal vesicle [46, 47]. The addition of Wnt4 to isolated metanephric mesenchyme induces expression of epithelial markers [48], and mice lacking Wnt4 fail to develop nephron tubules [46, 47]. The precise stages that Wnts function, such as if Wnt9b and Wnt4 act prior or subsequent to the formation of pre-apical domains, is unclear.

The mechanisms in which Wnt signaling induces MET are unknown. One possibility is that Wnts promote cell polarity. Indeed, Wnts signaling has been shown to regulate cadherin expression, and cadherins. are well known for their roles in establishing apical-basal polarity and tissue morphogenesis. For example, E-cadherin is required to initiate, but not maintain, apical-basal polarity in vitro [49]. Cadherins are also important in cellular compaction, as occurs during pretubular aggregate formation. During early embryogenesis, E-cadherin causes compaction of the morula, and antibodies that block homotypic interactions of E-cadherin decompact the morula [50]. Compaction itself may promote lumen formation, perhaps by inducing cellular differentiation, as occurs during tooth development [51]. Compaction also is accompanied by increased spatial confinement of cells, and this could hasten lumen formation. MDCK cells confined to a small micropatterned surface with limited cell spreading form lumens at a higher rate than unconfined cells, although this phenomenon only occurs on a collagen matrix [52].

Although E-cadherin is not expressed during nephron progenitor compaction (i.e. the pretubular aggregate stage) or during lumen initiation, several other cadherins are expressed. During progenitor compaction/aggregation and MET, there is a striking cadherin isotype switch in which Cadherin-11 in the cap mesenchyme is replaced by R-cadherin as it forms a pretubular aggregate. R-cadherin expression increases further as the renal vesicle forms, at which time cadherin-6 also becomes highly expressed [53–55]. Interestingly, Wnt9b induces R-cadherin expression [56] and Wnt4 induces cadherin-6 expression in developing kidneys [57]. However, while both R-cadherin and cadherin-6 null mice have a delay in MET [53, 54], overt defects in apical-basal polarization have not been reported. This may be a consequence of functional redundancy by other cadherin family members. Indeed, p120ctn, a cadherin adaptor that stabilizes the protein levels of several classical cadherins including R-cadherin and cadherin-6, is required for normal renal tubulogenesis [58]. Mice with conditional deletion of p120ctn from the metanephric mesenchyme have severe morphological defects at early tubule stages [58]. Additional experiments are needed to delineate p120ctn’s role in establishing apical-basal polarity and lumen formation.

Cytoskeleton and polarization

Morphogenetic changes in cell shape accompany the polarization process. As cells transition from the pretubular aggregate to renal vesicle stage, they become wedge-shaped and elongated along their radial axis, forming a rosette prior to overt lumen opening. In general, mechanisms driving rosette formation involve apical constriction and/or planar polarized constriction [59], both of which involve dynamic contraction of an actomyosin network. Indeed in nephron development, an actin focus exists at the central vertices of the rosette prior to lumen formation, suggesting an apical constriction [29]. In the absence of afadin, rosette formation does not occur [29]. As an F-actin binding protein, afadin might serve to couple adhesive complexes to actomyosin contractility, and a failure of this function may lead to defects in rosette formation.

Role of ECM in establishing polarity

Cell-matrix interactions are critical for the earliest steps of kidney development, yet their role in establishing apical-basal polarity in developing nephrons has not been studied. A well-established basal lamina from the ureteric bud lies adjacent to the cap mesenchyme. Within developing nephrons, fibronectin is expressed as early as the cap mesenchyme stage [60]. Laminin and collagen isoforms become evident as a discontinuous basal lamina in forming renal vesicles [61–63]. As renal vesicles mature, this basal lamina becomes continuous. The timing of the development of the basal lamina suggests that cell-matrix cues occur in concert with cell-cell interactions and the development of apical basal polarity. Certainly, cell-matrix signaling through integrins is a polarity determinant during polarization of MDCK cells [64].

II. Luminal expansion in the nephron

The composition of the luminal surface undergoes changes during renal vesicle growth. Par-3, initially apical, becomes redistributed to apical junctional complexes, and aPKC and Par6 are increased at the apical surface [29]. The process of epithelialization continues as the early renal vesicle transforms to its more mature state, including the late appearance of typical adherens junctions and tight junctions [65].

The early renal vesicle has a small lumen, but this subsequently enlarges as the renal vesicle itself enlarges. Because there is no evidence that centrally located cells undergo apoptosis during renal vesicle enlargement, luminal expansion likely does not occur via cavitation. The expansion is likely due, in part, to the increased number of cells comprising the maturing renal vesicle. For example, as discussed earlier, with each cell division, daughter cells will contribute new apical/luminal surface to the growing renal vesicle. However, there may also be an enlargement of the apical surface area per cell, as occurs in MDCK cysts via vesicular trafficking and apical exocytosis, the so-called hollowing mechanism [30]. In MDCK cysts, there are abundant Rab11-positive vesicles in the subapical region consistent with recycling endosomes [22]. Similar subapical vesicles have been observed in a number of other tubules, including those of the pancreatic and mammary epithelia, suggesting exocytosis may be a common mechanism for luminal expansion.

In addition to apical exocytosis, data from other organ systems suggests at least three other processes may have a role in nephron luminal expansion: fluid secretion; tight junction barrier formation; and membrane surface repulsion. Transepithelial ion transport is known to be critical for luminal fluid secretion and absorption in many tubules. Recently, it has been shown that lumen expansion is dependent on an anion antiporter Slc26aα in the notochord of the invertebrate chordate Ciona intestinalis [66]. This study shows that Slc26aα is required specifically for luminal expansion, rather than apical membrane specification or lumen formation. The luminal expansion is dependent on ion transport: point mutants in Scl26aα that block transport do not exhibit luminal expansion.

There is some evidence that the secretion of fluid secondary to directional ion transport may drive luminal expansion in the zebrafish gut [67]. Genetic absence of a negative regulator of the Cl− channel cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), or chemical activation of CFTR, leads to increased luminal size in vitro and widening of the zebrafish gut in vivo. This luminal expansion has been attributed to ion/fluid secretion, rather than effects on cell proliferation [68]. Interestingly, while CFTR is present in both the mature proximal and distal nephron, during development it is largely restricted to the apical ureteric epithelium [69], suggesting that transporters other than CFTR might function in luminal expansion of nascent nephrons.

Tight junction formation has been implicated in luminal expansion, although the data is indirect. Grainyhead-like 2 (Grhl2), a transcriptional activator expressed in the nephric duct and ureteric epithelium, is required for luminal expansion and barrier formation [70]. Mice lacking Grhl2 die at E11.5 prior to kidney development, however the lumen of the nephric duct is noticeably small. Consistent with this, MDCK cells lacking Grhl2 have small lumens and disruption of barrier formation. The small lumens may be partially due to reduced cell proliferation, as there appear to be decreased cells in cross section both in vivo and in vitro; however, there are likely other contributors. Most notably, Grhl2 induces expression of genes encoding claudin-4, E-cadherin and the small GTPase Rab25. In the absence of Grhl2, forced expression of claudin-4, a component of tight junctions, rescues barrier function. Claudin-4 will also rescue luminal expansion when co-expressed with Rab25, a constituent of Rab11-containing endosomes. Although Grhl2 may have pleiotrophic effects on lumen formation, this data has led to the hypothesis that Grhl2 regulates lumen expansion by “sealing” the epithelial barrier via claudin-4 and facilitating exocytosis of endosomes containing luminal components via Rab25.

Apical lumen membrane repulsion is a mechanism of luminal expansion in the Drosophila heart tube. During Drosophila heart development, two cardioblasts migrate toward each other to generate dorsal and ventral contacts between their opposing apical surfaces, thereby “entrapping” a central lumen (See Figure 1). During this process, a lumen forms because the central-most apical surfaces do not come into contact. Both Slit and its receptor, Robo, are apically localized in cardioblasts and required for an open lumen [15, 16]. This is thought to occur via repulsion of opposing apical surfaces based on Slit’s well-characterized role as a chemorepellant in axonal guidance [71, 72].

Membrane repulsion is also a potential mechanism of lumen expansion in the mouse dorsal aorta. Lammert et al. found that apically localized podocalyxin, a member of the CD34 family of sialomucins, is essential for lumen formation in the mouse aorta [73]. Its role in vascular lumen formation has been ascribed to electrostatic repulsion of opposing apical surfaces from negatively charged sialic acids on the extracellular domain of podocalyxin [74]. Indeed, removal of sialic acids or charge neutralization inhibits blood vessel lumen formation in mice [74].

Numerous in vitro studies have shown a central role for podocalyxin in epithelial polarity and it is tempting to ascribe its importance to its membrane repulsive characteristics, as has been described previously [75]. However, its role is likely far more complex and multi-faceted. Podocalyxin interacts directly with the adaptor proteins NHERF1/2 and Ezrin, forming a ternary complex at the apical surface that is tethered to the actin cytoskeleton through Ezrin [64, 76–78]. Polarized distribution of podocalyxin/NHERF to the free surface of single MDCK cells attached to a culture dish is an early event in epithelial polarization, and podocalyxin allows segregation of apical and basolateral domains in an epithelial monolayer [79]. Depletion of Podocalyxin from 3D MDCK cultures leads to multiple lumens with cytosolic redistribution of NHERF1 [64] and mislocalization of several apical proteins, such as Crb3, to sub-apical Rab11-positive vesicles. Interestingly, the phenotype is not one of absent or collapsed lumens, as might be expected from podocalyxin’s role in membrane repulsion. Consistent with these findings, individual depletion of Ezrin, or NHERF1, −2 or −3 also leads to multiple lumens [64]. Collectively, these results suggest a critical role for Podocalyxin/NHERF/Ezrin complexes in generating apical-basal polarity and a continuous apical surface.

Despite its essential role in MDCK lumen formation, podocalyxin expression in the kidney is largely limited to hematopoietic progenitors, vascular endothelia, and podocytes [80, 81]. It does not appear to be expressed in or required for the development of the nephron tubules, although it has a critical role in podocyte development [82]. Its lack of a role in renal epithelial tubule development is surprising, and it remains possible that other CD34 family members promote lumen formation in renal tubules in vivo.

III. Luminal elongation and nephron tubulogenesis

Following enlargement and luminal expansion of the renal vesicle, it undergoes cellular movements and proliferation to form an elongated structure called an extended renal vesicle (ERV). During its formation, the basal lamina separating the RV and UB is removed, and cells of the distal ERV invade the ureteric epithelium through a non-apoptotic mechanism, forming a single continuous nephron-ureteric bud tubule [65, 83]. This structure then forms its lumen by extension toward the ureteric bud tip and by discrete de novo lumen generation within the most distal portion of the extended renal vesicle (Figure 2). Ultimately, the nephron-ureteric bud lumens become continuous at the s-shaped body stage [29, 65]. Because the continuous lumen is generated after the tubule forms, the directionality of lumen extension may simply parallel the polarization process, although this is speculative. The “extending” portion of the lumen is present across the apical surface of many cells, rather than a luminal/apical extension from a single cell that burrows centrally through its neighboring cells. How adjacent lumens merge during this process is not known, and many questions remain. Do lumens fuse at any point along their luminal surface or only at cell-cell junctions? If only at cell-cell junctions, do lumens become closely approximated via an “unzippering” or rearrangement of adjacent cell-cell junctions? Do cellular movements such as cell intercalation and rosette formation bring lumens in close proximity for fusion? Does luminal extension depend on intraluminal pressure from fluid accumulation? Many of these questions will be challenging to answer and likely will require live imaging.

There is emerging data that components of cell-cell junctions are required to interconnect multiple lumens during nephrogenesis. For example, Afadin is required for continuous lumen formation in addition to its role in timely lumen initiation [29], although the mechanisms still need to be elucidated. While some of the s-shaped bodies lacking Afadin have abnormal shape, the delay in lumen formation and the discontinuous lumens arise prior to observable structural defects. This implies a primary defect in lumen formation per se. However, in Drosophila, Afadin (Canoe) has a role in germband extension, a convergent extension process required for body elongation, and it couples the actomyosin network to adherens junctions [84]. One possibility is that Afadin might couple adhesive complex remodeling to actomyosin contractility during tubule elongation. Indeed, nonmuscle myosin IIa and IIb are required for both normal tubule morphogenesis and continuous lumen formation in developing nephrons [85]. In the myosin IIa/b mutants, it is unclear which phenotype arises first, and if these defects are interdependent. As stated earlier, an actomyosin network is required for planar polarized constriction and apical constriction. For example, in Drosophila germ band extension, myosin II (Zipper) is critical for planar polarized rosette formation, which leads to cell intercalation and axis elongation [59, 86]. Distinct from this, myosin has a direct role in apical constriction: its intermittent localization to the luminal surface of cardioblasts coincides with constriction of that apical surface in live imaging [87].

The link between cellular movements and tubule/lumen lengthening has been demonstrated for elongation of the Xenopus proximal pronephric tubule and murine collecting ducts [45, 88]. In Xenopus, elongation of the pronephric tubule arises through cell intercalations and transient rosette formation that occur in a myosin II dependent fashion. There is constant shrinking and expansion of cellular junctions during the tubule lengthening [88]. Mouse collecting ducts also show evidence of rosette formation in static images [88], and have the long axis of cells perpendicular to the tubule axis [45, 88]. In addition, murine collecting ducts at early stages of kidney development have higher numbers of cells per cross sectional area than neonatal tubules [45, 89]. Because of these data, it has been hypothesized that transient rosette formation and cell intercalations drive collecting duct elongation, similar to the process in Xenopus pronephric tubules [45, 88]. It is possible that cell intercalations (also referred to as convergent extension) are also involved in elongation of mammalian nephron tubules, as in the collecting system, but this has not yet been shown.

During development of the zebrafish pronephros, groups of epithelia within the tubule migrate collectively while continuously maintaining their apical junctions and polarization [90]. Interestingly, blockage of tubule fluid flow by mechanical obstruction or impaired cardiac output disrupts these cell movements/migration and eliminates proximal tubule convolution. These results suggest that fluid flow itself is important for cell migration and tubule elongation. Whether or not fluid flow has an effect on lumen formation or remodeling of renal lumens is unknown.

Just as mitosis and orientation of cell division may contribute to the initiation of lumen formation, so may these processes contribute to elongation of a growing nephron tubule and it’s lumen. To date, however, evidence is lacking to support this notion within the kidney. In fact, prior to cell division, ureteric tip cells move into the lumen, where they undergo mitosis and then reinsert/intercalate into the epithelial layer [91]. It is not known if the orientation of this luminal mitosis is critical, and if ureteric bud stalk cells (or other renal epithelia) have a similar behavior. Data from murine collecting tubules suggests that spindle orientation is random during embryogenesis and until shortly after birth [45]. In this case, tubule elongation is hypothesized to result mainly from cell intercalations/convergent extension, as described above. However, it is interesting to note that during mammary duct development, which forms a stratified epithelium postnatally, the stratification occurs when luminal/apical cells divide perpendicularly to the lumen and basal lamina [92]. During these asymmetric divisions, only the mother cell retains its apical surface. This indirectly implies that duct length may be determined by the orientation of cell division in the mammary epithelium.

Orientation of cell division is also important in hepatic epithelial cells for lumen placement, which may drive branching of the hepatic tubules. During liver embryogenesis, hepatocytes divide perpendicularly to their luminal surface (called the bile canaliculi), leading to asymmetric inheritance of the lumen [13, 14]. This creates numerous isolated lumens, which later interconnect. In this manner, a highly branched tubular network is generated.

One question that has arisen is how do adjacent lumens fuse during early nephron tubulogenesis as the tubule is elongating? Little is known to date. Two models have arisen from studies of the anastomoses of zebrafish segmental arteries during embryogenesis [93]. The first is a model in which lumens are brought in close proximity via cellular rearrangements, and then the lumens adjoin along their junctional surfaces through rearrangements of the cell-cell junctions. The second is one in which separate lumens evaginate into an intervening (non-lumenized) cell, hollowing it until the two lumens converge and fuse.

In an additional study of zebrafish cranial vessel anastomoses, two vessels have been shown to contact each other via sprouts from their tip cells and form a cadherin-based junction that expands into a ring like structure [94]. At the center of this ring, new apical membrane is generated, which ultimately fuses with the existing lumens. Whether or not the luminal fusions occurred at the junctional sites is unclear. Remarkably, the continuous, perfused lumens of the vascular anastomoses are not always stable, with many showing temporary collapse and rearrangements of the apical membrane [94]. This suggests a highly dynamic process with constant remodeling. It will be interesting to determine the similarities of nephron lumenogenesis to these other models.

IV Beyond development: tubule lumens in maintenance and cystic kidney disease

Although the creation of new nephrons ceases prior to birth in humans (and within several days of birth in mice)[95], there is tremendous tubule elongation and maturation that occurs postnatally. Once completed, little is known of mechanisms that maintain patency of lumens. Indeed, we have limited knowledge of renal tubule remodeling in basal states.

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by abnormal dilation of renal epithelial tubules. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common form in humans and is caused by mutations in Pkd1 or Pkd2 [96, 97]. A central feature of the cystic tubules is a striking loss of apical basal polarity. Several apical proteins and transporters are mislocalized to the basolateral surface, and conversely, basolateral proteins localize to the apical surface [2]. One prominent example in ADPKD patients is the mislocalization of Na+/K+-ATPase, which relocalizes to the apical surface [98].

One of the outstanding questions in PKD is whether defects in apical basal polarity per se have a causative role in cyst formation in human PKD. Several animal models with mutations in polarity proteins (e.g. Crb3 knockout mice [99]) give rise to cystic kidneys, yet many do not [100]. One potential explanation for models that lack a cystic phenotype is that organisms may have tremendous functional redundancy in polarity due to its paramount importance. However, the pathogenesis of cyst formation is highly complex, and the impact of abnormal apical basal polarity on cystogenesis is unknown.

In ADPKD, PKD1 has been shown to interact with cadherin complexes [101–103] and with Par3 [89]. E-cadherin is mislocalized in cysts from ADPKD patients [104], and PKD1 may regulate recruitment of E-cadherin to the plasma membrane [102]. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) that lack PKD1 have mislocalized Par3 and altered stoichiometry of Par complex interactions. Specifically, MEFs lacking PKD1 have reduced Par3 interaction with aPKC and increased Par6 interaction with aPKC. PKD1 was also found to interact with both Par3 and aPKC [89]. Furthermore, mice lacking Par3 from the ureteric epithelia show mild dilation of tubules [89]. However, polarity defects were not observed in these Par3 mutants. Rather, the tubules had increased cell number in cross section and altered orientation of the long axis of cells, suggesting a defect in cell intercalation/convergent extension. Indeed mice carrying Pkd1 alleles that lack the c-terminal, intercellular tail in UB epithelia also have a phenotype consistent with abnormal cell intercalation/convergent extension [89]. Previous studies have shown that both Par3 and PKD1 are required for establishing front-rear polarity in migrating cells, and their absence reduces directional migration of cells [89, 105, 106]. One possibility is that defects in front-rear polarity and abnormal cellular movements/intercalation combine to cause abnormal tubule development and abnormal remodeling in mature tubules, which results in cystic dilation of tubules. While intriguing, this remains speculative. The relationship between apical basal polarity, front-rear polarity, and convergent extension (planar polarity) is not clear. The roles of individual proteins in these processes may vary based on cellular context, making these processes interdependent. In short, proteins classically considered to play roles in apical basal polarity may also participate in other types of polarity.

Just as intraluminal fluid accumulation may contribute to lumen expansion during development, excessive fluid accumulation can cause cystic dilation of tubules. Elevated cAMP signaling is thought to be a primary driver for the increased fluid accumulation (and increased cell proliferation) that occurs in cystic tubules [107]. Elevated cAMP signaling leads to activation of apical transporters, including CFTR, which drives chloride secretion into the lumen, secondarily causing sodium and water secretion [68, 108]. The net water influx causes cyst enlargement. This overexpansion can be blocked using CFTR inhibitors, which partially rescue cyst size in a mouse model of ADPKD [109]. It can also be inhibited in mice and humans by vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists, which inhibit cAMP production [110, 111].

In addition to abnormal cellular movements/intercalation and increased intraluminal fluid in cystic tubules, increased epithelial cell proliferation is thought to be a major contributor to ADPKD pathogenesis [107]. It is unknown how abnormal apical basal polarity affects cell proliferation in ADPKD. In general, the relationship between polarity and proliferation is complex, and cell type and context dependent. Loss of polarity could induce apoptosis or proliferation, which may occur in a cell autonomous or non-cell autonomous fashion. One possible link between polarity and proliferation is through the Hippo signaling pathway, which orchestrates the balance between proliferation and apoptosis [112]. In ADPKD, Hippo signaling in cystic tubules appears to be increased, which would promote cell proliferation [113]. In support of this, the absence of Fat4, a negative regulator of Hippo signaling, leads to polycystic disease in mice [114], although it is important to note that Fat4 is involved in planar polarity as well. Importantly, several polarity protein complexes negatively regulate Hippo signaling [115], implying that altered function of these complexes could lead to unrestrained Hippo signaling and thus cell proliferation.

Finally, in PKD there has been considerable effort to determine the role of oriented cell division in cyst development and this is still an area of some debate (Reviewed in [100]). At least one compelling study refutes the hypothesis that defects in orientation of cell division cause or initiate cyst formation. This study shows that pre-cystic tubules in mouse models lacking PKD1 or PKD2 do not have misorientation of cell division [116]. This study also identified a mouse model that has misorientation of cell division in the absence of cystic tubules. These results are consistent with the studies on developing collecting ducts discussed earlier; namely that other processes such as convergent extension are primary drivers of tubule length and diameter [45]. It is interesting to note, however, that in ADPKD some cysts appear to be detached and discontinuous with a tubule [117]. How this arises is unknown, but there may be similarities to the discontinuous lumens observed in mutants of polarity proteins, such as Cdc42 and Par3, which are accompanied by defects in oriented cell division [38, 40, 118]. Further work is needed to elucidate these concepts.

Summary

Generation of nephron tubules requires at least three general processes. At the onset are epithelialization and apical-basal polarization, which initiates lumen formation. This is followed by lumen expansion. Finally, a dynamic set of cell movements drives tubule morphogenesis and lumen elongation. During each of these processes, multiple activities within each individual cell are coordinated with adjacent cells and with the extracellular environment. Some of the concepts and molecules integral for distinct events during tubulogenesis, such as the role of afadin/nectin signaling, are only now beginning to emerge. As our knowledge grows, new questions arise. One in particular that promises to be an exciting new area of study is the role of the microenvironment and other cell types (e.g. stroma and vasculature) in polarization and tubulogenesis. Additionally, causal links between defects in apical basal polarization and disease pathogenesis of various human congenital and acquired renal diseases have yet to be established. Further progress in these areas would open up new avenues for novel therapeutics. In all, renal tubulogenesis is an intricate and beautiful process, an example of the wonders of nature and the mysteries we strive to unravel.

Acknowledgments

I thank David Bryant, Tom Carroll and reviewers for comments on the manuscript. This review was supported by Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Research Award No. 5-FY13-201 from the March of Dimes Foundation, Satellite Healthcare Coplon Grant, and NIH R01DK099478.

Abbreviations

- MM

metanephric mesenchyme

- UB

ureteric bud

- CM

cap mesenchyme

- PA

pretubular aggregate

- RV

renal vesicle

- MET

mesenchymal to epithelial transition

- PKD

polycystic kidney disease

References

- 1.Schluter MA, Margolis B. Apical lumen formation in renal epithelia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(7):1444–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008090949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson PD. Apico-basal polarity in polycystic kidney disease epithelia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812(10):1239–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delous M, et al. Nephrocystin-1 and nephrocystin-4 are required for epithelial morphogenesis and associate with PALS1/PATJ and Par6. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(24):4711–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donaldson JC, et al. Nephrocystin-conserved domains involved in targeting to epithelial cell-cell junctions, interaction with filamins, and establishing cell polarity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(32):29028–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halaoui R, McCaffrey L. Rewiring cell polarity signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34(8):939–50. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee DB, Huang E, Ward HJ. Tight junction biology and kidney dysfunction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290(1):F20–34. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00052.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iruela-Arispe ML, Beitel GJ. Tubulogenesis. Development. 2013;140(14):2851–5. doi: 10.1242/dev.070680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datta A, Bryant DM, Mostov KE. Molecular regulation of lumen morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2011;21(3):R126–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubarsky B, Krasnow MA. Tube morphogenesis: making and shaping biological tubes. Cell. 2003;112(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maruyama R, Andrew DJ. Drosophila as a model for epithelial tube formation. Dev Dyn. 2012;241(1):119–35. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buechner M. Tubes and the single C. elegans excretory cell. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12(10):479–84. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bar T, Guldner FH, Wolff JR. “Seamless” endothelial cells of blood capillaries. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;235(1):99–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00213729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazaro-Dieguez F, et al. Par1b links lumen polarity with LGN-NuMA positioning for distinct epithelial cell division phenotypes. J Cell Biol. 2013;203(2):251–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201303013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slim CL, et al. Par1b induces asymmetric inheritance of plasma membrane domains via LGN-dependent mitotic spindle orientation in proliferating hepatocytes. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(12):e1001739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medioni C, et al. Genetic control of cell morphogenesis during Drosophila melanogaster cardiac tube formation. J Cell Biol. 2008;182(2):249–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santiago-Martinez E, et al. Repulsion by Slit and Roundabout prevents Shotgun/E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion during Drosophila heart tube lumen formation. J Cell Biol. 2008;182(2):241–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mailleux AA, Overholtzer M, Brugge JS. Lumen formation during mammary epithelial morphogenesis: insights from in vitro and in vivo models. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(1):57–62. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.1.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzlinger DA, Easton TG, Ojakian GK. The MDCK epithelial cell line expresses a cell surface antigen of the kidney distal tubule. J Cell Biol. 1982;93(2):269–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popsueva A, et al. GDNF promotes tubulogenesis of GFRalpha1-expressing MDCK cells by Src-mediated phosphorylation of Met receptor tyrosine kinase. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(1):119–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang MJ, et al. Ureteric bud outgrowth in response to RET activation is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Dev Biol. 2002;243(1):128–36. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Belmonte F, et al. Cell-polarity dynamics controls the mechanism of lumen formation in epithelial morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2008;18(7):507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant DM, et al. A molecular network for de novo generation of the apical surface and lumen. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(11):1035–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schluter MA, et al. Trafficking of Crumbs3 during cytokinesis is crucial for lumen formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(22):4652–63. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grobstein C. Inductive epitheliomesenchymal interaction in cultured organ rudiments of the mouse. Science. 1953;118(3054):52–5. doi: 10.1126/science.118.3054.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grobstein C. Trans-filter induction of tubules in mouse metanephrogenic mesenchyme. Exp Cell Res. 1956;10(2):424–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(56)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cebrian C, et al. Morphometric index of the developing murine kidney. Dev Dyn. 2004;231(3):601–8. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Short KM, et al. Global quantification of tissue dynamics in the developing mouse kidney. Dev Cell. 2014;29(2):188–202. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saxen L, Wartiovaara J. Cell contact and cell adhesion during tissue organization. Int J Cancer. 1966;1(3):271–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Z, et al. De novo lumen formation and elongation in the developing nephron: a central role for afadin in apical polarity. Development. 2013;140(8):1774–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.087957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrari A, et al. ROCK-mediated contractility, tight junctions and channels contribute to the conversion of a preapical patch into apical surface during isochoric lumen initiation. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 21):3649–63. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jose M, et al. Robust polarity establishment occurs via an endocytosis-based cortical corralling mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):407–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201206081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris KP, Tepass U. Cdc42 and vesicle trafficking in polarized cells. Traffic. 2010;11(10):1272–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li D, et al. FIP5 phosphorylation during mitosis regulates apical trafficking and lumenogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2014;15(4):428–37. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T, et al. Cytokinesis defines a spatial landmark for hepatocyte polarization and apical lumen formation. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 11):2483–92. doi: 10.1242/jcs.139923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morais-de-Sa E, Sunkel C. Adherens junctions determine the apical position of the midbody during follicular epithelial cell division. EMBO Rep. 2013;14(8):696–703. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schober M, Schaefer M, Knoblich JA. Bazooka recruits Inscuteable to orient asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature. 1999;402(6761):548–51. doi: 10.1038/990135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wodarz A, et al. Bazooka provides an apical cue for Inscuteable localization in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nature. 1999;402(6761):544–7. doi: 10.1038/990128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hao Y, et al. Par3 controls epithelial spindle orientation by aPKC-mediated phosphorylation of apical Pins. Curr Biol. 2010;20(20):1809–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durgan J, et al. Par6B and atypical PKC regulate mitotic spindle orientation during epithelial morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(14):12461–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.174235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaffe AB, et al. Cdc42 controls spindle orientation to position the apical surface during epithelial morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2008;183(4):625–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng Z, et al. LGN regulates mitotic spindle orientation during epithelial morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2010;189(2):275–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raj A, et al. Stochastic mRNA synthesis in mammalian cells. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(10):e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raj A, et al. Variability in gene expression underlies incomplete penetrance. Nature. 2010;463(7283):913–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunskill EW, et al. Single cell dissection of early kidney development: multilineage priming. Development. 2014;141(15):3093–101. doi: 10.1242/dev.110601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karner CM, et al. Wnt9b signaling regulates planar cell polarity and kidney tubule morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):793–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stark K, et al. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature. 1994;372(6507):679–83. doi: 10.1038/372679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kispert A, Vainio S, McMahon AP. Wnt-4 is a mesenchymal signal for epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney. Development. 1998;125(21):4225–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanigawa S, et al. Wnt4 induces nephronic tubules in metanephric mesenchyme by a non-canonical mechanism. Dev Biol. 2011;352(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capaldo CT, Macara IG. Depletion of E-cadherin disrupts establishment but not maintenance of cell junctions in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(1):189–200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson MH, Maro B, Takeichi M. The role of cell adhesion in the synchronization and orientation of polarization in 8-cell mouse blastomeres. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1986;93:239–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mammoto T, et al. Mechanochemical control of mesenchymal condensation and embryonic tooth organ formation. Dev Cell. 2011;21(4):758–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez-Fraticelli AE, et al. Cell confinement controls centrosome positioning and lumen initiation during epithelial morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2012;198(6):1011–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dahl U, et al. Genetic dissection of cadherin function during nephrogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(5):1474–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.5.1474-1487.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mah SP, et al. Kidney development in cadherin-6 mutants: delayed mesenchyme-to-epithelial conversion and loss of nephrons. Dev Biol. 2000;223(1):38–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho EA, et al. Differential expression and function of cadherin-6 during renal epithelium development. Development. 1998;125(5):803–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karner CM, et al. Canonical Wnt9b signaling balances progenitor cell expansion and differentiation during kidney development. Development. 2011;138(7):1247–57. doi: 10.1242/dev.057646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valerius MT, McMahon AP. Transcriptional profiling of Wnt4 mutant mouse kidneys identifies genes expressed during nephron formation. Gene Expr Patterns. 2008;8(5):297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marciano DK, et al. p120 catenin is required for normal renal tubulogenesis and glomerulogenesis. Development. 2011;138(10):2099–109. doi: 10.1242/dev.056564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harding MJ, McGraw HF, Nechiporuk A. The roles and regulation of multicellular rosette structures during morphogenesis. Development. 2014;141(13):2549–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.101444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ekblom P. Formation of basement membranes in the embryonic kidney: an immunohistological study. J Cell Biol. 1981;91(1):1–10. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miner JH. Developmental biology of glomerular basement membrane components. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1998;7(1):13–9. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199801000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ekblom P, et al. Induction of a basement membrane glycoprotein in embryonic kidney: possible role of laminin in morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77(1):485–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saxen L. In: Organogenesis of the Kidney. Barlow PW, Green PB, Wylie CC, editors. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. (Developmental and Cell Biology Series). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bryant DM, et al. A molecular switch for the orientation of epithelial cell polarization. Dev Cell. 2014;31(2):171–87. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kao RM, et al. Invasion of distal nephron precursors associates with tubular interconnection during nephrogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(10):1682–90. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deng W, et al. Anion translocation through an Slc26 transporter mediates lumen expansion during tubulogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(37):14972–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220884110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bagnat M, et al. Cse1l is a negative regulator of CFTR-dependent fluid secretion. Curr Biol. 2010;20(20):1840–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li H, Findlay IA, Sheppard DN. The relationship between cell proliferation, Cl− secretion, and renal cyst growth: a study using CFTR inhibitors. Kidney Int. 2004;66(5):1926–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Devuyst O, et al. Developmental regulation of CFTR expression during human nephrogenesis. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(3 Pt 2):F723–35. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.3.F723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aue A, et al. A Grainyhead-Like 2/Ovo-Like 2 Pathway Regulates Renal Epithelial Barrier Function and Lumen Expansion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014080759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brose K, et al. Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell. 1999;96(6):795–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Slit is the midline repellent for the robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;96(6):785–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strilic B, et al. The molecular basis of vascular lumen formation in the developing mouse aorta. Dev Cell. 2009;17(4):505–15. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Strilic B, et al. Electrostatic cell-surface repulsion initiates lumen formation in developing blood vessels. Curr Biol. 2010;20(22):2003–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takeda T, et al. Expression of podocalyxin inhibits cell-cell adhesion and modifies junctional properties in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(9):3219–32. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Orlando RA, et al. The glomerular epithelial cell anti-adhesin podocalyxin associates with the actin cytoskeleton through interactions with ezrin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(8):1589–98. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1281589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmieder S, et al. Podocalyxin activates RhoA and induces actin reorganization through NHERF1 and Ezrin in MDCK cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(9):2289–98. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000135968.49899.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takeda T, et al. Loss of glomerular foot processes is associated with uncoupling of podocalyxin from the actin cytoskeleton. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(2):289–301. doi: 10.1172/JCI12539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meder D, et al. Gp135/podocalyxin and NHERF-2 participate in the formation of a preapical domain during polarization of MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(2):303–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kerjaschki D, Sharkey DJ, Farquhar MG. Identification and characterization of podocalyxin–the major sialoprotein of the renal glomerular epithelial cell. J Cell Biol. 1984;98(4):1591–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nielsen JS, McNagny KM. CD34 is a key regulator of hematopoietic stem cell trafficking to bone marrow and mast cell progenitor trafficking in the periphery. Microcirculation. 2009;16(6):487–96. doi: 10.1080/10739680902941737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Doyonnas R, et al. Anuria, omphalocele, and perinatal lethality in mice lacking the CD34-related protein podocalyxin. J Exp Med. 2001;194(1):13–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Georgas K, et al. Analysis of early nephron patterning reveals a role for distal RV proliferation in fusion to the ureteric tip via a cap mesenchyme-derived connecting segment. Dev Biol. 2009;332(2):273–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sawyer JK, et al. A contractile actomyosin network linked to adherens junctions by Canoe/afadin helps drive convergent extension. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(14):2491–508. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Recuenco MC, et al. Nonmuscle Myosin II Regulates the Morphogenesis of Metanephric Mesenchyme-Derived Immature Nephrons. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(5):1081–91. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bertet C, Sulak L, Lecuit T. Myosin-dependent junction remodelling controls planar cell intercalation and axis elongation. Nature. 2004;429(6992):667–71. doi: 10.1038/nature02590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vogler G, et al. Cdc42 and formin activity control non-muscle myosin dynamics during Drosophila heart morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2014;206(7):909–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201405075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lienkamp SS, et al. Vertebrate kidney tubules elongate using a planar cell polarity-dependent, rosette-based mechanism of convergent extension. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1382–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Castelli M, et al. Polycystin-1 binds Par3/aPKC and controls convergent extension during renal tubular morphogenesis. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2658. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vasilyev A, et al. Collective cell migration drives morphogenesis of the kidney nephron. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(1):e9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Packard A, et al. Luminal mitosis drives epithelial cell dispersal within the branching ureteric bud. Dev Cell. 2013;27(3):319–30. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huebner RJ, Lechler T, Ewald AJ. Developmental stratification of the mammary epithelium occurs through symmetry-breaking vertical divisions of apically positioned luminal cells. Development. 2014;141(5):1085–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.103333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Herwig L, et al. Distinct cellular mechanisms of blood vessel fusion in the zebrafish embryo. Curr Biol. 2011;21(22):1942–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lenard A, et al. In vivo analysis reveals a highly stereotypic morphogenetic pathway of vascular anastomosis. Dev Cell. 2013;25(5):492–506. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hartman HA, Lai HL, Patterson LT. Cessation of renal morphogenesis in mice. Dev Biol. 2007;310(2):379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Germino GG, et al. Positional cloning approach to the dominant polycystic kidney disease gene, PKD1. Kidney Int Suppl. 1993;39:S20–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mochizuki T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996;272(5266):1339–42. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wilson PD, et al. Reversed polarity of Na(+) -K(+) -ATPase: mislocation to apical plasma membranes in polycystic kidney disease epithelia. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(3 Pt 2):F420–30. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.260.3.F420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Whiteman EL, et al. Crumbs3 is essential for proper epithelial development and viability. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(1):43–56. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00999-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fedeles S, Gallagher AR. Cell polarity and cystic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(8):1161–72. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2337-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huan Y, van Adelsberg J. Polycystin-1, the PKD1 gene product, is in a complex containing E-cadherin and the catenins. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(10):1459–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Streets AJ, et al. Homophilic and heterophilic polycystin 1 interactions regulate E-cadherin recruitment and junction assembly in MDCK cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 9):1410–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Roitbak T, et al. A polycystin multiprotein complex constitutes a cholesterol-containing signalling microdomain in human kidney epithelia. Biochem J. 2005;392(Pt 1):29–38. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Charron AJ, et al. Compromised cytoarchitecture and polarized trafficking in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(1):111–24. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pegtel DM, et al. The Par-Tiam1 complex controls persistent migration by stabilizing microtubule-dependent front-rear polarity. Curr Biol. 2007;17(19):1623–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yao G, et al. Polycystin-1 regulates actin cytoskeleton organization and directional cell migration through a novel PC1-Pacsin 2-N-Wasp complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(10):2769–79. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wallace DP. Cyclic AMP-mediated cyst expansion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812(10):1291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Davidow CJ, et al. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mediates transepithelial fluid secretion by human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease epithelium in vitro. Kidney Int. 1996;50(1):208–18. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yang B, et al. Small-molecule CFTR inhibitors slow cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1300–10. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007070828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gattone VH, 2nd, et al. Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med. 2003;9(10):1323–6. doi: 10.1038/nm935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Torres VE, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2407–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yu FX, Zhao B, Guan KL. Hippo Pathway in Organ Size Control, Tissue Homeostasis, and Cancer. Cell. 2015;163(4):811–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Happe H, et al. Altered Hippo signalling in polycystic kidney disease. J Pathol. 2011;224(1):133–42. doi: 10.1002/path.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Saburi S, et al. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40(8):1010–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Grzeschik NA, et al. Lgl, aPKC, and Crumbs regulate the Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway through two distinct mechanisms. Curr Biol. 2010;20(7):573–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nishio S, et al. Loss of oriented cell division does not initiate cyst formation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(2):295–302. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Grantham JJ, Geiser JL, Evan AP. Cyst formation and growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1987;31(5):1145–52. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Elias BC, et al. Cdc42 regulates epithelial cell polarity and cytoskeletal function during kidney tubule development. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(23):4293–305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.164509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mandai K, et al. Afadin/AF-6 and canoe: roles in cell adhesion and beyond. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;116:433–54. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394311-8.00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]