Significance

Myostatin, via activation of the Smad2/3 pathway, has long been recognized as the body’s major negative regulator of skeletal muscle mass. In this study, however, we demonstrate that other TGF-β proteins, particularly activin A and activin B, act in concert with myostatin to repress muscle growth. Preventing activin and myostatin signaling in the tibialis anterior muscles of mice resulted in massive hypertrophy (>150%), which was dependent upon both the complete inhibition of the Smad2/3 pathway and activation of the parallel bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/Smad1/5 axis. Using this approach in models of muscular dystrophy and cancer cachexia increased muscle mass or prevented muscle wasting, respectively, highlighting the potential therapeutic advantages of complete inhibition of Smad2/3 ligand activity in skeletal muscle.

Keywords: myostatin, activin, BMP, muscle, hypertrophy

Abstract

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) network of ligands and intracellular signaling proteins is a subject of intense interest within the field of skeletal muscle biology. To define the relative contribution of endogenous TGF-β proteins to the negative regulation of muscle mass via their activation of the Smad2/3 signaling axis, we used local injection of adeno-associated viral vectors (AAVs) encoding ligand-specific antagonists into the tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of C57BL/6 mice. Eight weeks after AAV injection, inhibition of activin A and activin B signaling produced moderate (∼20%), but significant, increases in TA mass, indicating that endogenous activins repress muscle growth. Inhibiting myostatin induced a more profound increase in muscle mass (∼45%), demonstrating a more prominent role for this ligand as a negative regulator of adult muscle mass. Remarkably, codelivery of activin and myostatin inhibitors induced a synergistic response, resulting in muscle mass increasing by as much as 150%. Transcription and protein analysis indicated that this substantial hypertrophy was associated with both the complete inhibition of the Smad2/3 pathway and activation of the parallel bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/Smad1/5 axis (recently identified as a positive regulator of muscle mass). Analyses indicated that hypertrophy was primarily driven by an increase in protein synthesis, but a reduction in ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation pathways was also observed. In models of muscular dystrophy and cancer cachexia, combined inhibition of activins and myostatin increased mass or prevented muscle wasting, respectively, highlighting the potential therapeutic advantages of specifically targeting multiple Smad2/3-activating ligands in skeletal muscle.

Myostatin, a member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, is a powerful negative regulator of skeletal muscle mass in mammalian species. Mice lacking myostatin have twice the muscle mass of normal mice, due to a combination of an increased number of muscle fibers (hyperplasia) and increased fiber size (hypertrophy) (1, 2). Similar increases in musculature are observed in cattle, sheep, dogs, and humans carrying a loss-of-function mutation in the myostatin gene (3, 4). Myostatin negatively regulates the growth and morphogenesis of skeletal muscle by binding to activin type I (ALK4 or ALK5) and type II receptors (ActRIIA/B) and stimulating the Smad2/3 transcription pathway (5). Smad2/3 activation leads to dephosphorylation and nuclear retention of the transcription factor FOXO3, which induces expression of the ubiquitin ligases MuRF-1 and atrogin-1 (6). These ligases stimulate degradation of myofibrillar proteins, such as myosin, by the ubiquitin–proteasome system (7). Smad2/3 activation also results in dephosphorylation, and therefore repression, of Akt, the key intermediary molecule mediating insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1)-stimulated protein synthesis in muscle (8). Thus, the net effect of myostatin signaling in muscle is to limit protein synthesis and increase protein degradation, thereby maintaining homeostasis of muscle mass.

Myostatin is synthesized as a precursor molecule consisting of an N-terminal prodomain and a C-terminal mature domain. Dimeric precursors are cleaved by proprotein convertases, whereupon myostatin is secreted from the cell noncovalently associated with its prodomains (9). Extracellularly, prodomain binding maintains myostatin in a latent form, which requires BMP-1/tolloid-like metalloprotease activation (10). Several groups have exploited the fact that myostatin is naturally inhibited by its own prodomain by delivering a modified form of this molecule to WT mice and mice modeling musculoskeletal disorders (11, 12). In both young and aged mice, prodomain-mediated inhibition of myostatin increased muscle mass between 20% and 30% (11, 12). Mechanistically, the myostatin prodomain promoted muscle hypertrophy via inhibition of proteolytic pathways (13). Importantly, administration of the myostatin prodomain also enhanced muscle growth and ameliorated dystrophic pathophysiology in mdx mice, a murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) (14).

Importantly, recent studies have indicated that myostatin is not the only TGF-β family member that negatively regulates muscle growth (15, 16). Treating WT and dystrophic mdx mice with soluble ActRIIB, or a neutralizing antibody targeting this pleiotropic receptor, increased muscle mass 30 to 60% (17–19), which is significantly greater than the level of hypertrophy observed with inhibition of myostatin alone. Delivery of follistatin, a binding protein for multiple TGF-β ligands, resulted in even more profound hypertrophy (>100%) in adult mice (16, 20). An examination of muscle weights in activin A and activin B heterozygous mice led Lee et al. (16) to suggest that activins may be the other ligands that are regulated by soluble ActRIIB and follistatin in muscle. To test this hypothesis directly, we developed specific activin antagonists based on modified prodomains and overexpressed these molecules in skeletal muscle using recombinant serotype-6 adeno-associated viral vectors (AAVs) (21). Blocking activin A alone, or both activin A and activin B together, resulted in significant increases (11 to 14%) in muscle mass in WT mice, and markedly greater effects in Mstn−/− mice (17 to 50%) (21).

Although the canonical TGF-β signaling pathway represses skeletal muscle growth and can promote muscle wasting, recent studies have identified the parallel bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-Smad1/5 pathway as an important positive regulator of muscle mass (22, 23). Supporting this concept, increasing the expression of BMP7, or the activity of BMP receptors in muscle, leads to Smad1/5-dependent muscle fiber hypertrophy (23). Conversely, inhibition of BMP signaling exacerbates wasting in response to denervation or fasting and abolishes hypertrophy in myostatin-deficient mice (22, 23). Thus, under normal circumstances, a balance between the Smad2/3 and Smad1/5 pathways is required to maintain muscle mass (24).

The realization that multiple TGF-β family ligands cooperate with, or oppose, myostatin activity, via competition for the same receptor complexes and Smad-signaling proteins, provides an excellent opportunity to develop refined strategies to treat muscle-wasting diseases. In this study, we used myostatin and activin prodomains, alone or in combination, to induce graded increases in muscle mass and examined whether these inhibitors are capable of protecting against muscle wasting in murine models of muscular dystrophy and cancer cachexia.

Results

Myostatin and Activins Synergize to Regulate Muscle Mass.

To determine the relative contribution of endogenous TGF-β ligands to the negative regulation of muscle mass, we used local injection of AAV vectors encoding either the myostatin prodomain (inhibits myostatin and the closely related ligand, GDF11) (Fig. S1A), a modified activin A prodomain (specifically inhibits activin A) (21), or a modified activin B prodomain (inhibits activin A and activin B) (21) into the tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of WT C57BL/6 mice. Eight weeks post-AAV injections, the activin A and activin B prodomains produced significant (13 to 20%) increases in TA mass (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1B). The comparable increase in muscle mass induced by blocking activin A alone, or both activin isoforms together, suggests that endogenous activin A is a particularly important repressor of muscle growth. Inhibiting myostatin induced a more profound increase in muscle mass (45%) (Fig. 1A), consistent with the idea that this ligand is the dominant regulator of adult muscle mass. Strikingly, when the myostatin prodomain was codelivered with either activin prodomain, we observed a synergistic response, resulting in muscle mass increasing by as much as 156% (Fig. 1A). Expression of the various prodomains was confirmed in treated TA muscles by Western blot for FLAG (Fig. 1B). Histological analysis, using hematoxylin and eosin staining of the prodomain-treated TA muscles, revealed normal muscle architecture, with a progressive increase in myofiber size as each additional Smad2/3-activating ligand was inhibited (Fig. 1 C and D).

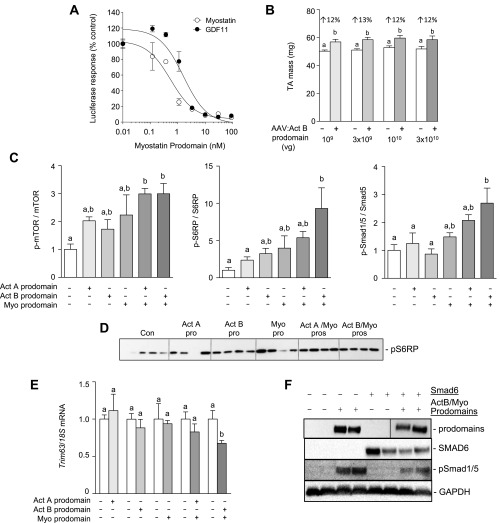

Fig. S1.

Specificity of the myostatin prodomain and effect of inhibiting activin and myostatin signaling on protein synthesis, protein degradation, and Smad1/5 pathways. (A) The myostatin prodomain blocks myostatin- or GDF11-induced activation of a Smad2/3-responsive luciferase reporter in HEK293T cells. (B) Demonstration that the standard dose of AAV:Act B prodomain (1010 vg) used in this study is saturating for endogenous activins (n = 5–6, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (C) Densitometric analysis of Western blots probed for total and phosphorylated forms of mTOR, S6RP, and Smad1/5 in response to activin and myostatin inhibition (n = 5, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (D) Expanded Western blot (n = 4–5 TAs) of S6RP phosphorylation in response to prodomain treatment. (E) qRT-PCR analysis was used to assess mRNA expression of Trim63 (Murf1) in muscles of WT mice treated with prodomains (n = 5–6, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (F) Western blot analysis of TA muscles was used to assess prodomain and Smad6 expression and the phosphorylation of Smad1/5. For the prodomain Western blot, two lanes, representing samples not related to the results for this paper, were spliced out (black line).

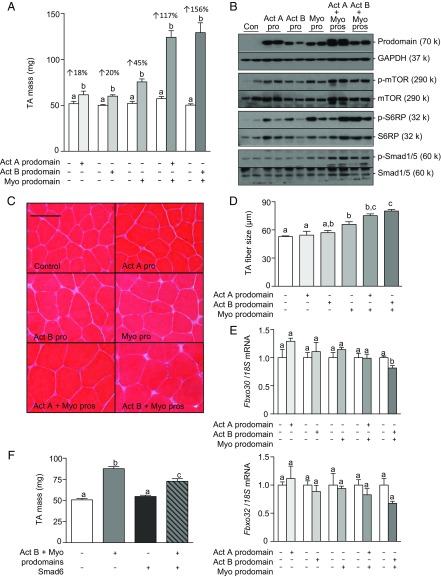

Fig. 1.

Myostatin and activins synergize to regulate muscle mass. The right tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of 6- to 8-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice were injected with AAVs encoding for modified activin A prodomain, activin B prodomain, and/or myostatin prodomain (left TA muscles were injected with equivalent doses of an AAV lacking a transgene). (A) Eight weeks post-AAV injection, the TA muscles were harvested and weighed (n = 4–6, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (B) Western blot analysis was used to assess prodomain expression and the phosphorylation of mTOR, S6RP, and Smad1/5. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of TA muscles was performed on cryosections. (Scale bar: 100 µm.) (D) Muscle fiber size was quantified (n = 3, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05; at least 150 myofibers were counted per TA muscle). (E) qRT-PCR was used to assess mRNA levels of Fbxo30 and Fbxo32 in response to activin/myostatin inhibition (n = 5, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (F) The right tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of 6- to 8-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice were injected with AAVs encoding for the activin B/myostatin prodomains, Smad6, or the three vectors combined (left TA muscles were injected with equivalent doses of an AAV lacking a transgene). Eight weeks post-AAV injection, the TA muscles were harvested and weighed (n = 4–6, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05).

Increased myofiber size was associated with enhanced phosphorylation of effector molecules downstream of Akt in the protein synthesis pathway (mTOR and S6RP) (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 C and D); however, the expression of key atrophy-related genes, including Fbxo32 (Atrogin-1), Fbxo30 (Musa1), and Trim63 (MuRF1), was only marginally decreased (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1E). We investigated whether the substantial hypertrophy observed upon codelivery of activin B and myostatin prodomains was due to both (i) the inhibition of the growth-repressing Smad2/3 pathway and (ii) activation of the parallel growth-promoting bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/Smad1/5 axis (22, 23). Phosphorylation of Smad1/5 was only substantially increased when both activin and myostatin signaling was suppressed (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1C). To test the importance of the BMP-Smad1/5 pathway in the observed skeletal muscle hypertrophy, we codelivered AAV6 vectors expressing the activin B and myostatin prodomains, together with a vector encoding for the BMP pathway inhibitor, Smad6, to TA muscles. In this experiment, muscles were harvested 3 wk after AAV injections, at which time the increase in mass (74%) after prodomain overexpression (Fig. 1F) was half that observed after overexpression for 8 wk (156%) (Fig. 1A). Although administration of AAV:Smad6 alone had no effect on muscle mass, coadministration of AAV:Smad6 significantly reduced the muscle hypertrophy induced by the combined effects of the activin B and myostatin prodomains (Fig. 1F). In this setting, Smad6 significantly reduced, but did not completely ablate, phosphorylation of Smad1/5 (Fig. S1F). These data demonstrate that activation of Smad1/5 signaling is an important component of the massive hypertrophy observed upon complete inhibition of the Smad2/3 pathway in skeletal muscle.

The Transcriptomic Signature of Prodomain-Induced Muscle Hypertrophy.

Because blocking activin A/B or myostatin signaling increased muscle mass 20% and 45%, respectively, while inhibiting these ligands together triggered a synergistic increase in mass, we sought to understand the mechanisms underlying these effects. Quantifying the transcriptome of muscles treated with various prodomain combinations for 8 wk by RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) revealed that only 44 and 181 genes were significantly regulated by activin B prodomain or myostatin prodomain treatment, respectively, relative to AAV:MCS injected control TA muscles (adjusted P value <0.1, ±1.5-fold) (Tables S1 and S2). To identify pathways that are involved in the regulation of muscle hypertrophy in the myostatin prodomain-treated mice, we used the DAVID Bioinformatic Database. This analysis identified the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy signaling pathways, both of which have previously been implicated in muscle growth and development after myostatin inhibition (25). Supporting the literature, 24 of the 181 myostatin prodomain-regulated genes have been shown to promote, or protect against, cardiac hypertrophy (bold genes, Table S2). We verified the RNA-Seq findings for Actc1 using qRT-PCR (Fig. S2A). Together, these results indicate that myostatin functions, in part, to inhibit an adaptive process in skeletal muscle with similarities to the hypertrophy-type response of myocardium.

Table S1.

Activin B prodomain-regulated genes in the tibialis anterior muscle of C57BL/6 mice (adjusted P value <0.1, ±1.5-fold)

| ID | logFC | Average expression | t | P value | Adjusted P value | B |

| Inhbb | 8.358 | 6.808 | 24.101 | 1.67E−13 | 2.15E−9 | 12.356 |

| Sdf2l1 | 1.695 | 2.699 | 5.314 | 0.000084 | 0.043135 | 0.885 |

| Manf | 1.576 | 4.697 | 7.182 | 0.000003 | 0.006392 | 4.548 |

| Mthfd2 | 1.557 | 3.205 | 5.004 | 0.000152 | 0.055989 | 0.479 |

| Dnajb9 | 1.497 | 4.806 | 5.513 | 0.000057 | 0.035174 | 1.993 |

| Hspa5 | 1.262 | 8.095 | 13.135 | 1.09E−9 | 0.000007 | 11.982 |

| Mstn | 1.097 | 8.611 | 5.983 | 0.000024 | 0.022065 | 2.890 |

| Ostn | 1.089 | 2.731 | 4.494 | 0.000418 | 0.084062 | −0.282 |

| Mybph | 1.086 | 6.508 | 5.642 | 0.000045 | 0.033340 | 2.285 |

| Pdk4 | 1.076 | 9.114 | 5.460 | 0.000063 | 0.036029 | 1.937 |

| Pdia6 | 1.010 | 6.137 | 7.736 | 0.000001 | 0.003903 | 5.652 |

| Hspa13 | 1.010 | 3.714 | 4.330 | 0.000582 | 0.099879 | −0.166 |

| Slc25a32 | 0.975 | 2.946 | 5.121 | 0.000121 | 0.049815 | 0.771 |

| Magt1 | 0.823 | 5.245 | 5.937 | 0.000026 | 0.022413 | 2.775 |

| Hsp90b1 | 0.800 | 7.163 | 7.523 | 0.000002 | 0.004390 | 5.402 |

| Pdia4 | 0.780 | 4.296 | 4.297 | 0.000622 | 0.105358 | −0.144 |

| Hyou1 | 0.743 | 5.678 | 5.403 | 0.000071 | 0.037883 | 1.876 |

| Col24a1 | 0.731 | 3.417 | 4.283 | 0.000639 | 0.106943 | −0.293 |

| Dstn | 0.698 | 4.568 | 4.634 | 0.000316 | 0.078897 | 0.476 |

| Cd36 | 0.682 | 8.232 | 4.759 | 0.000246 | 0.071542 | 0.624 |

| Calr | 0.678 | 7.691 | 6.838 | 0.000005 | 0.007605 | 4.334 |

| Spcs3 | 0.677 | 5.362 | 4.586 | 0.000348 | 0.078897 | 0.388 |

| Dnajc3 | 0.677 | 5.637 | 7.062 | 0.000004 | 0.006689 | 4.619 |

| Canx | 0.671 | 6.723 | 7.838 | 0.000001 | 0.003903 | 5.851 |

| Golt1b | 0.650 | 4.121 | 4.575 | 0.000355 | 0.078897 | 0.331 |

| Cd164 | 0.637 | 6.870 | 5.173 | 0.000110 | 0.048671 | 1.442 |

| Vimp | 0.635 | 4.508 | 5.452 | 0.000064 | 0.036029 | 1.914 |

| Ssr3 | 0.623 | 7.696 | 6.310 | 0.000013 | 0.015603 | 3.454 |

| Amot | 0.614 | 7.089 | 4.482 | 0.000428 | 0.084576 | 0.128 |

| Arf4 | 0.613 | 5.115 | 4.709 | 0.000272 | 0.072939 | 0.622 |

| Tmed10 | 0.596 | 6.088 | 5.078 | 0.000132 | 0.049920 | 1.282 |

| Fam134b | 0.585 | 7.027 | 4.339 | 0.000571 | 0.099348 | −0.164 |

| Xbp1 | 0.580 | 6.600 | 6.141 | 0.000018 | 0.017843 | 3.168 |

| Tmed7 | 0.578 | 5.047 | 4.696 | 0.000279 | 0.073432 | 0.597 |

| Herpud1 | 0.577 | 7.252 | 5.563 | 0.000052 | 0.033627 | 2.140 |

| Ppp1r3a | 0.577 | 7.990 | 4.426 | 0.000479 | 0.090761 | −0.015 |

| Amhr2 | −0.672 | 4.499 | −4.816 | 0.000220 | 0.069735 | 0.816 |

| Cyr61 | −0.696 | 5.534 | −5.280 | 0.000089 | 0.043585 | 1.649 |

| Mpp3 | −0.708 | 5.579 | −5.210 | 0.000102 | 0.046960 | 1.518 |

| Pmepa1 | −0.770 | 4.264 | −4.907 | 0.000184 | 0.065878 | 0.976 |

| Mttp | −0.953 | 2.399 | −4.812 | 0.000222 | 0.069735 | 0.482 |

| Igfn1 | −1.028 | 5.568 | −4.532 | 0.000387 | 0.080382 | 0.229 |

| Mss51 | −1.091 | 4.941 | −6.977 | 0.000004 | 0.006760 | 4.544 |

| Ildr1 | −1.954 | 0.328 | −5.095 | 0.000128 | 0.049815 | −0.546 |

Table S2.

Myostatin prodomain-regulated genes in the tibialis anterior muscle of C57BL/6 mice (adjusted P value <0.1, ±1.5-fold)

| ID | logFC | Average expression | t | P value | Adjusted P value | B |

| Mstn | 5.970 | 8.611 | 33.746 | 1.10E−15 | 1.42E−11 | 21.881 |

| Kif11 | 4.994 | −0.450 | 5.386 | 0.0000730 | 0.0154074 | −1.523 |

| Tll2 | 4.528 | −0.770 | 4.133 | 0.0008676 | 0.0555880 | −2.344 |

| Ebi3 | 3.893 | −1.373 | 3.921 | 0.0013355 | 0.0626559 | −2.579 |

| Bub1 | 3.610 | −2.706 | 3.974 | 0.0012002 | 0.0599795 | −2.774 |

| Prc1 | 3.407 | −0.188 | 3.716 | 0.0020351 | 0.0753171 | −2.645 |

| Gm4841 | 3.368 | 7.780 | 4.984 | 0.0001583 | 0.0245664 | 0.973 |

| Acox2 | 3.341 | −1.122 | 3.501 | 0.0031702 | 0.0923722 | −2.897 |

| Adora1 | 3.056 | 1.066 | 5.149 | 0.0001148 | 0.0186390 | −0.601 |

| Kif15 | 3.044 | −1.562 | 3.954 | 0.0012481 | 0.0599795 | −2.657 |

| Pglyrp2 | 3.039 | −1.239 | 3.722 | 0.0020110 | 0.0748553 | −2.741 |

| F830016B08Rik | 2.882 | 6.260 | 3.963 | 0.0012273 | 0.0599795 | −0.861 |

| Iigp1 | 2.734 | 7.092 | 4.388 | 0.0005175 | 0.0450300 | −0.179 |

| Foxp3 | 2.644 | −0.296 | 3.572 | 0.0027413 | 0.0858666 | −2.742 |

| C130080G10Rik | 2.621 | 3.896 | 4.941 | 0.0001722 | 0.0249115 | 0.812 |

| Oas3 | 2.529 | 0.177 | 3.957 | 0.0012423 | 0.0599795 | −2.035 |

| Il2rb | 2.459 | 2.355 | 3.701 | 0.0021007 | 0.0770784 | −1.460 |

| Slamf8 | 2.427 | 1.279 | 3.599 | 0.0025899 | 0.0832480 | −1.948 |

| Irgm2 | 2.325 | 7.301 | 5.257 | 0.0000933 | 0.0169303 | 1.471 |

| Kif23 | 2.278 | −0.203 | 3.835 | 0.0015940 | 0.0667054 | −2.481 |

| Mki67 | 2.208 | 1.756 | 3.441 | 0.0035919 | 0.0986894 | −2.030 |

| Top2a | 2.185 | 1.465 | 3.451 | 0.0035137 | 0.0977380 | −2.115 |

| Actc1 | 2.172 | 7.478 | 7.522 | 0.0000017 | 0.0027471 | 5.429 |

| Igtp | 2.065 | 7.103 | 3.957 | 0.0012407 | 0.0599795 | −1.085 |

| Mybph | 1.922 | 6.508 | 10.332 | 2.93E−8 | 0.0000756 | 9.224 |

| B230312C02Rik | 1.713 | 5.332 | 12.545 | 2.07E−9 | 0.0000089 | 11.202 |

| E2f1 | 1.655 | 0.856 | 3.466 | 0.0034106 | 0.0956985 | −2.183 |

| Lyz1 | 1.605 | 3.697 | 3.616 | 0.0025024 | 0.0821334 | −1.374 |

| Cd86 | 1.531 | 1.443 | 3.624 | 0.0024619 | 0.0817181 | −1.671 |

| Gbp10 | 1.378 | 5.593 | 3.879 | 0.0014567 | 0.0644747 | −1.102 |

| Gbp4 | 1.295 | 5.784 | 3.646 | 0.0023518 | 0.0805724 | −1.590 |

| Mpeg1 | 1.284 | 5.622 | 3.502 | 0.0031686 | 0.0923722 | −1.838 |

| Adamts20 | 1.256 | 2.924 | 4.096 | 0.0009349 | 0.0576234 | −0.559 |

| Cycs | 1.183 | 3.526 | 4.181 | 0.0007869 | 0.0542508 | −0.346 |

| Haus3 | 1.178 | 1.599 | 3.666 | 0.0022571 | 0.0792080 | −1.478 |

| Itga4 | 1.169 | 4.491 | 5.898 | 0.0000280 | 0.0107283 | 2.727 |

| Fras1 | 1.167 | 2.590 | 3.469 | 0.0033859 | 0.0955794 | −1.656 |

| Ak4 | 1.129 | 3.339 | 4.953 | 0.0001682 | 0.0248985 | 1.023 |

| Serpinb1a | 1.117 | 3.589 | 4.663 | 0.0002982 | 0.0344740 | 0.451 |

| Lpar6 | 1.112 | 2.056 | 3.593 | 0.0026238 | 0.0838508 | −1.459 |

| Sh3bgrl | 1.091 | 3.946 | 3.439 | 0.0036015 | 0.0986894 | −1.744 |

| Nabp1 | 1.077 | 3.771 | 3.671 | 0.0022346 | 0.0790516 | −1.287 |

| Trp53inp1 | 1.060 | 3.617 | 4.291 | 0.0006290 | 0.0502656 | −0.144 |

| Il33 | 1.029 | 2.745 | 3.492 | 0.0032294 | 0.0934637 | −1.596 |

| Etv4 | 1.010 | 2.343 | 3.511 | 0.0031067 | 0.0913579 | −1.581 |

| Ap1s2 | 1.001 | 4.987 | 4.398 | 0.0005068 | 0.0445111 | −0.031 |

| Col24a1 | 0.999 | 3.417 | 6.115 | 0.0000189 | 0.0083924 | 2.967 |

| Slc7a2 | 0.987 | 6.669 | 4.806 | 0.0002245 | 0.0291996 | 0.588 |

| Aspa | 0.968 | 2.487 | 4.403 | 0.0005016 | 0.0445111 | −0.059 |

| Dock10 | 0.967 | 3.003 | 3.724 | 0.0020033 | 0.0748553 | −1.179 |

| Atp13a3 | 0.965 | 4.612 | 4.432 | 0.0004736 | 0.0441957 | 0.071 |

| Dnajb9 | 0.960 | 4.806 | 3.491 | 0.0032386 | 0.0935190 | −1.761 |

| Ostn | 0.957 | 2.731 | 3.987 | 0.0011688 | 0.0599695 | −0.747 |

| Bche | 0.953 | 2.343 | 3.494 | 0.0032207 | 0.0934229 | −1.621 |

| Irf8 | 0.945 | 4.974 | 3.446 | 0.0035523 | 0.0983866 | −1.897 |

| Il12a | 0.939 | 2.516 | 4.155 | 0.0008286 | 0.0552898 | −0.482 |

| Eif2s3y | 0.934 | 5.105 | 4.735 | 0.0002586 | 0.0323302 | 0.569 |

| Frzb | 0.911 | 5.901 | 7.127 | 0.0000033 | 0.0038174 | 4.803 |

| Atp11c | 0.888 | 2.450 | 3.688 | 0.0021559 | 0.0785655 | −1.269 |

| Pdk4 | 0.887 | 9.114 | 4.502 | 0.0004107 | 0.0406870 | −0.089 |

| Zbtb33 | 0.885 | 2.961 | 3.780 | 0.0017865 | 0.0710116 | −1.078 |

| Rnpc3 | 0.860 | 2.800 | 3.750 | 0.0019007 | 0.0728547 | −1.135 |

| Il15 | 0.858 | 3.376 | 3.687 | 0.0021606 | 0.0785655 | −1.262 |

| Sh3bp2 | 0.853 | 3.485 | 3.973 | 0.0012013 | 0.0599795 | −0.726 |

| Tpmt | 0.819 | 2.767 | 3.831 | 0.0016066 | 0.0667448 | −0.987 |

| Mettl21c | 0.810 | 5.465 | 3.539 | 0.0029344 | 0.0897673 | −1.817 |

| Gm7120 | 0.809 | 4.287 | 3.858 | 0.0015219 | 0.0664425 | −1.021 |

| Cacnb3 | 0.805 | 2.900 | 3.916 | 0.0013516 | 0.0626559 | −0.834 |

| Ube2d3 | 0.804 | 6.484 | 4.245 | 0.0006906 | 0.0512610 | −0.504 |

| Gbp9 | 0.799 | 4.047 | 3.977 | 0.0011927 | 0.0599795 | −0.755 |

| Aldh9a1 | 0.784 | 3.399 | 4.083 | 0.0009595 | 0.0576234 | −0.525 |

| Naa30 | 0.783 | 4.278 | 4.076 | 0.0009740 | 0.0576234 | −0.595 |

| Serpinb9 | 0.772 | 3.566 | 4.039 | 0.0010507 | 0.0586864 | −0.609 |

| Xpo1 | 0.767 | 4.716 | 3.633 | 0.0024150 | 0.0809965 | −1.501 |

| Dcun1d1 | 0.765 | 4.060 | 3.663 | 0.0022710 | 0.0794043 | −1.360 |

| Dtx3l | 0.762 | 4.559 | 3.723 | 0.0020073 | 0.0748553 | −1.311 |

| Prkg1 | 0.755 | 5.372 | 4.275 | 0.0006502 | 0.0503210 | −0.334 |

| Prkag2 | 0.748 | 4.398 | 4.436 | 0.0004692 | 0.0441073 | 0.093 |

| Tnfsf10 | 0.741 | 4.046 | 3.603 | 0.0025684 | 0.0832480 | −1.472 |

| Nipa2 | 0.741 | 4.076 | 3.851 | 0.0015425 | 0.0665041 | −1.010 |

| Slc25a32 | 0.732 | 2.946 | 3.842 | 0.0015726 | 0.0667054 | −0.971 |

| Ppp1r3a | 0.728 | 7.990 | 5.618 | 0.0000471 | 0.0133823 | 2.094 |

| Amot | 0.727 | 7.089 | 5.361 | 0.0000766 | 0.0155425 | 1.648 |

| Nudt7 | 0.725 | 4.797 | 3.747 | 0.0019120 | 0.0730295 | −1.327 |

| Tmed5 | 0.723 | 4.540 | 4.278 | 0.0006455 | 0.0503210 | −0.223 |

| Cacna2d1 | 0.720 | 8.489 | 5.226 | 0.0000991 | 0.0174757 | 1.342 |

| Kctd12 | 0.720 | 4.713 | 3.521 | 0.0030459 | 0.0908069 | −1.706 |

| Crls1 | 0.720 | 3.735 | 3.616 | 0.0025033 | 0.0821334 | −1.421 |

| Zfand6 | 0.697 | 6.188 | 4.675 | 0.0002907 | 0.0343536 | 0.367 |

| Sh3kbp1 | 0.696 | 5.836 | 5.817 | 0.0000325 | 0.0107283 | 2.562 |

| Actr2 | 0.690 | 5.298 | 4.660 | 0.0002997 | 0.0344740 | 0.440 |

| Kras | 0.687 | 4.522 | 3.811 | 0.0016748 | 0.0683683 | −1.136 |

| Rnf139 | 0.683 | 5.647 | 4.814 | 0.0002208 | 0.0290194 | 0.682 |

| Ift122 | 0.672 | 4.799 | 4.193 | 0.0007669 | 0.0542508 | −0.402 |

| Tbc1d4 | 0.670 | 4.169 | 4.035 | 0.0010583 | 0.0586864 | −0.681 |

| Cd164 | 0.666 | 6.870 | 5.450 | 0.0000646 | 0.0145880 | 1.823 |

| Cmpk1 | 0.665 | 3.852 | 3.448 | 0.0035350 | 0.0981186 | −1.739 |

| Rpl15 | 0.662 | 3.938 | 3.829 | 0.0016145 | 0.0668573 | −1.049 |

| Rnf115 | 0.661 | 6.369 | 6.983 | 0.0000042 | 0.0039010 | 4.557 |

| Slc25a46 | 0.660 | 5.864 | 5.234 | 0.0000976 | 0.0174523 | 1.473 |

| Osbpl8 | 0.653 | 4.001 | 3.480 | 0.0033139 | 0.0952638 | −1.702 |

| Bcap29 | 0.653 | 4.745 | 4.639 | 0.0003123 | 0.0349273 | 0.436 |

| Ccnd1 | 0.648 | 4.500 | 3.615 | 0.0025063 | 0.0821334 | −1.488 |

| Stom | 0.644 | 6.457 | 5.828 | 0.0000319 | 0.0107283 | 2.545 |

| Fabp3 | 0.644 | 7.006 | 4.010 | 0.0011136 | 0.0590226 | −1.023 |

| Shisa5 | 0.642 | 5.194 | 4.085 | 0.0009559 | 0.0576234 | −0.685 |

| Tab3 | 0.640 | 3.070 | 3.631 | 0.0024278 | 0.0810050 | −1.350 |

| Tmem56 | 0.637 | 5.332 | 3.638 | 0.0023939 | 0.0809218 | −1.594 |

| Ptpla | 0.637 | 5.095 | 4.257 | 0.0006738 | 0.0504515 | −0.335 |

| Ociad2 | 0.626 | 6.044 | 7.313 | 0.0000024 | 0.0034360 | 5.096 |

| Lamp2 | 0.621 | 6.174 | 3.900 | 0.0013953 | 0.0632771 | −1.168 |

| Usp14 | 0.618 | 5.493 | 6.319 | 0.0000131 | 0.0061790 | 3.461 |

| Itm2a | 0.610 | 7.355 | 7.542 | 0.0000017 | 0.0027471 | 5.443 |

| Tbc1d19 | 0.606 | 4.368 | 3.808 | 0.0016874 | 0.0685538 | −1.140 |

| Rap2c | 0.605 | 5.059 | 3.590 | 0.0026417 | 0.0840437 | −1.651 |

| Rnf13 | 0.601 | 5.309 | 5.603 | 0.0000484 | 0.0133823 | 2.200 |

| Aldh1l2 | 0.600 | 3.767 | 3.517 | 0.0030696 | 0.0908819 | −1.604 |

| Acap2 | 0.598 | 4.143 | 4.957 | 0.0001669 | 0.0248985 | 1.072 |

| Irs1 | 0.583 | 6.619 | 5.861 | 0.0000300 | 0.0107283 | 2.595 |

| Gadd45b | −0.558 | 4.883 | −4.971 | 0.0001625 | 0.0246157 | 0.995 |

| Heyl | −0.573 | 4.307 | −3.982 | 0.0011787 | 0.0599795 | −0.838 |

| Cbx7 | −0.588 | 4.726 | −4.485 | 0.0004253 | 0.0415012 | 0.081 |

| Pitpnm3 | −0.599 | 3.812 | −3.627 | 0.0024483 | 0.0814762 | −1.461 |

| Cdh23 | −0.606 | 3.786 | −3.870 | 0.0014839 | 0.0652651 | −1.010 |

| Aldh1l1 | −0.608 | 3.330 | −3.752 | 0.0018925 | 0.0728547 | −1.164 |

| Magix | −0.612 | 5.197 | −4.972 | 0.0001621 | 0.0246157 | 0.957 |

| Myod1 | −0.621 | 5.725 | −3.473 | 0.0033582 | 0.0952638 | −2.038 |

| Dpep1 | −0.623 | 4.096 | −4.610 | 0.0003314 | 0.0362234 | 0.400 |

| Asb2 | −0.623 | 9.342 | −3.836 | 0.0015903 | 0.0667054 | −1.441 |

| Smtnl1 | −0.635 | 5.165 | −3.988 | 0.0011653 | 0.0599695 | −0.957 |

| Efcab6 | −0.639 | 4.232 | −5.376 | 0.0000744 | 0.0154527 | 1.803 |

| Tbx1 | −0.647 | 5.895 | −4.685 | 0.0002851 | 0.0339986 | 0.374 |

| Bhlhe40 | −0.654 | 6.949 | −5.514 | 0.0000573 | 0.0139333 | 1.914 |

| Lrp4 | −0.661 | 4.620 | −5.624 | 0.0000465 | 0.0133823 | 2.246 |

| Clcn6 | −0.667 | 2.764 | −4.015 | 0.0011037 | 0.0588302 | −0.651 |

| Abtb2 | −0.669 | 4.449 | −4.422 | 0.0004825 | 0.0445111 | −0.001 |

| Nmrk2 | −0.670 | 8.434 | −4.918 | 0.0001802 | 0.0253617 | 0.740 |

| Svep1 | −0.675 | 4.024 | −4.135 | 0.0008624 | 0.0555433 | −0.473 |

| Acbd4 | −0.686 | 4.604 | −6.341 | 0.0000126 | 0.0061790 | 3.506 |

| 2310015B20Rik | −0.690 | 4.429 | −4.080 | 0.0009664 | 0.0576234 | −0.694 |

| Mb | −0.702 | 11.623 | −3.992 | 0.0011553 | 0.0599695 | −1.119 |

| Cxxc5 | −0.711 | 4.742 | −3.910 | 0.0013677 | 0.0626854 | −1.019 |

| Amhr2 | −0.729 | 4.499 | −5.356 | 0.0000772 | 0.0155425 | 1.757 |

| Fam53b | −0.732 | 6.105 | −5.145 | 0.0001158 | 0.0186390 | 1.240 |

| Ankrd23 | −0.737 | 11.215 | −4.535 | 0.0003847 | 0.0393215 | −0.027 |

| Gas1 | −0.745 | 4.348 | −3.915 | 0.0013521 | 0.0626559 | −0.966 |

| Mpp3 | −0.746 | 5.579 | −5.582 | 0.0000503 | 0.0133823 | 2.087 |

| Cdkn1c | −0.748 | 4.419 | −4.785 | 0.0002339 | 0.0298199 | 0.700 |

| Ramp1 | −0.764 | 5.510 | −6.519 | 0.0000092 | 0.0061790 | 3.778 |

| Nos1 | −0.799 | 5.242 | −4.095 | 0.0009358 | 0.0576234 | −0.752 |

| Sctr | −0.810 | 3.442 | −4.918 | 0.0001801 | 0.0253617 | 1.001 |

| Itgb5 | −0.818 | 6.608 | −6.856 | 0.0000051 | 0.0039010 | 4.320 |

| Htra3 | −0.819 | 5.103 | −5.804 | 0.0000333 | 0.0107283 | 2.552 |

| Cyr61 | −0.826 | 5.534 | −6.336 | 0.0000127 | 0.0061790 | 3.455 |

| Adcy2 | −0.850 | 4.824 | −6.881 | 0.0000049 | 0.0039010 | 4.407 |

| Bri3 | −0.851 | 3.009 | −4.730 | 0.0002612 | 0.0323401 | 0.646 |

| Myh8 | −0.862 | 4.439 | −4.086 | 0.0009532 | 0.0576234 | −0.652 |

| Fxyd6 | −0.874 | 5.463 | −5.515 | 0.0000572 | 0.0139333 | 1.981 |

| Gpx3 | −0.887 | 7.138 | −6.881 | 0.0000049 | 0.0039010 | 4.351 |

| Gm16062 | −0.905 | 1.769 | −3.840 | 0.0015773 | 0.0667054 | −1.011 |

| Srebf1 | −0.909 | 6.260 | −5.580 | 0.0000505 | 0.0133823 | 2.068 |

| Panx1 | −0.915 | 3.749 | −6.482 | 0.0000098 | 0.0061790 | 3.713 |

| Vtn | −0.974 | 4.412 | −5.746 | 0.0000371 | 0.0116606 | 2.476 |

| Pnpla3 | −1.020 | 3.445 | −3.833 | 0.0016022 | 0.0667448 | −1.029 |

| Fgfr4 | −1.040 | 1.695 | −3.744 | 0.0019218 | 0.0730295 | −1.199 |

| Dusp26 | −1.059 | 5.244 | −8.939 | 0.0000002 | 0.0004218 | 7.505 |

| Prima1 | −1.112 | 1.693 | −3.802 | 0.0017064 | 0.0690330 | −1.044 |

| Mfap2 | −1.135 | 2.011 | −4.018 | 0.0010967 | 0.0588302 | −0.731 |

| Pmepa1 | −1.139 | 4.264 | −7.183 | 0.0000030 | 0.0038174 | 4.868 |

| Adamts8 | −1.168 | 2.354 | −4.258 | 0.0006722 | 0.0504515 | −0.239 |

| Scx | −1.207 | 2.131 | −4.515 | 0.0004005 | 0.0399862 | 0.192 |

| Ddah1 | −1.263 | 3.378 | −5.513 | 0.0000573 | 0.0139333 | 2.071 |

| Mttp | −1.265 | 2.399 | −6.353 | 0.0000123 | 0.0061790 | 3.210 |

| Npff | −1.358 | 0.688 | −4.274 | 0.0006503 | 0.0503210 | −0.678 |

| Igfn1 | −1.515 | 5.568 | −6.594 | 0.0000081 | 0.0057841 | 3.893 |

| Brsk1 | −1.550 | 0.243 | −3.768 | 0.0018305 | 0.0719798 | −1.771 |

| Tmem100 | −1.588 | 3.007 | −5.659 | 0.0000436 | 0.0130555 | 2.299 |

| Sez6 | −1.682 | −0.452 | −3.533 | 0.0029677 | 0.0902023 | −2.205 |

| Dkk3 | −1.717 | 5.061 | −12.200 | 3.04E−9 | 0.0000098 | 11.365 |

| Mss51 | −2.086 | 4.941 | −12.592 | 1.96E−9 | 0.0000089 | 11.787 |

| Ildr1 | −2.107 | 0.328 | −5.542 | 0.0000543 | 0.0139333 | 0.907 |

Bold genes have been shown to promote or protect against cardiac hypertrophy.

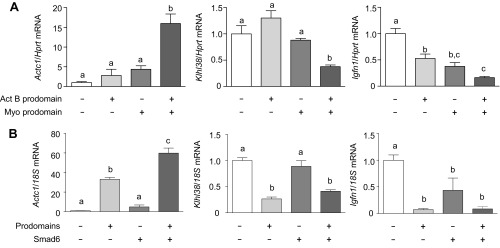

Fig. S2.

Verification of RNA-Seq analysis of prodomain-treated TA muscles. (A) qRT-PCR analysis was used to assess mRNA expression of Actc1, Klhl38, and Igfn1 in TA muscles of WT mice treated with activin B and/or myostatin prodomains. (B) The effect of Smad6 on prodomain-induced changes in the mRNA expression of Actc1, Klhl38, and Igfn1 in TA muscles of WT mice (n = 5, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05).

Another objective of the transcriptome analysis was to identify the genes that contribute to the synergistic hypertrophic response when all Smad2/3-activating ligands are inhibited. However, using the cutoffs above, 3,849 genes changed significantly when muscles were treated with activin B and myostatin prodomains, relative to control. Even using more stringent cutoff criteria (adjusted P value <0.05, ±twofold), 1,290 genes were significantly regulated. To better delineate genes that contribute to the synergistic response, our dataset was compared with gene changes reported previously in response to follistatin (26), which, like prodomains, fully inhibits Smad2/3 signaling and activates the Smad1/5 pathway. By this comparison, we identified 217 genes that were significantly regulated (adjusted P value <0.05, ±twofold) by both prodomain and follistatin treatment (Table S3). Up-regulated genes included those involved in the protein synthesis pathway (Slc7a5, Lat2, and Igf2) and myoblast differentiation (Tceal7) whereas a group of E3 ubiquitin ligase-associated genes linked to protein degradation (Kbtbd13, Asb2, Asb11, Klhl33, Klhl34, and Klhl38) were significantly down-regulated. qRT-PCR was used to verify some of these findings (Fig. S2A).

Table S3.

Genes regulated by cotreatment of tibialis anterior muscle of C57BL/6 mice with activin B and myostatin prodomains (adjusted P value <0.1, ±1.5-fold), which have previously been shown to be similarly regulated by follistatin treatment (25)

| ID | logFC | Average expression | t | P value | Adjusted P value | B |

| C130080G10Rik | 4.807 | 3.896 | 9.347 | 1.10E−7 | 0.000007 | 7.636 |

| Mt3 | 4.734 | 1.803 | 6.980 | 0.000004 | 0.000081 | 4.071 |

| Actc1 | 4.619 | 7.478 | 16.135 | 5.87E−11 | 4.72E−8 | 15.488 |

| F830016B08Rik | 4.530 | 6.260 | 6.306 | 0.000013 | 0.000185 | 3.318 |

| Gm4841 | 4.307 | 7.780 | 6.380 | 0.000012 | 0.000170 | 3.269 |

| Ccl8 | 3.988 | 3.443 | 4.771 | 0.000241 | 0.001425 | 0.698 |

| Mybph | 3.914 | 6.508 | 21.458 | 9.25E−13 | 3.97E−9 | 19.159 |

| Cd84 | 3.810 | 1.810 | 5.731 | 0.000038 | 0.000375 | 2.066 |

| Serpinb1a | 3.757 | 3.589 | 17.172 | 2.39E−11 | 2.80E−8 | 14.596 |

| Adora1 | 3.609 | 1.066 | 6.208 | 0.000016 | 0.000208 | 2.105 |

| Zbp1 | 3.499 | 2.326 | 5.259 | 0.000093 | 0.000716 | 1.536 |

| Ctss | 3.433 | 5.036 | 7.644 | 0.000001 | 0.000039 | 5.581 |

| Iigp1 | 3.402 | 7.092 | 5.491 | 0.000060 | 0.000518 | 1.627 |

| Retnla | 3.297 | 3.617 | 5.662 | 0.000043 | 0.000411 | 2.320 |

| Sln | 3.263 | 1.726 | 3.931 | 0.001308 | 0.005248 | −0.807 |

| Ccr2 | 3.203 | 3.977 | 7.602 | 0.000002 | 0.000040 | 5.552 |

| B230312C02Rik | 3.200 | 5.332 | 24.091 | 1.68E−13 | 1.08E−9 | 20.112 |

| Clec4a3 | 3.174 | 1.639 | 5.162 | 0.000112 | 0.000810 | 1.331 |

| Lyz1 | 3.159 | 3.697 | 7.506 | 0.000002 | 0.000044 | 5.380 |

| Ccl6 | 3.159 | 3.360 | 5.315 | 0.000084 | 0.000664 | 1.704 |

| Cd48 | 3.122 | 1.557 | 6.050 | 0.000021 | 0.000254 | 2.701 |

| Ly86 | 2.994 | 2.041 | 5.572 | 0.000051 | 0.000465 | 2.093 |

| Gbp6 | 2.986 | 3.519 | 4.284 | 0.000638 | 0.002969 | −0.234 |

| Mt2 | 2.930 | 3.202 | 4.323 | 0.000589 | 0.002800 | −0.150 |

| Ptprc | 2.904 | 4.114 | 6.854 | 0.000005 | 0.000094 | 4.351 |

| Aldh1a2 | 2.846 | 2.647 | 8.097 | 0.000001 | 0.000024 | 5.993 |

| H2-DMb1 | 2.819 | 3.208 | 6.995 | 0.000004 | 0.000079 | 4.579 |

| Mthfd2 | 2.812 | 3.205 | 9.618 | 7.58E−8 | 0.000006 | 8.074 |

| Fam65b | 2.802 | 2.582 | 10.066 | 4.15E−8 | 0.000004 | 8.350 |

| Zdbf2 | 2.797 | 1.061 | 5.828 | 0.000032 | 0.000333 | 2.272 |

| Fbxl22 | 2.779 | 2.822 | 8.354 | 4.66E−7 | 0.000018 | 6.525 |

| Ccl9 | 2.719 | 3.009 | 6.175 | 0.000017 | 0.000216 | 3.222 |

| Spi1 | 2.714 | 2.481 | 6.578 | 0.000008 | 0.000131 | 3.798 |

| H2-Aa | 2.639 | 7.471 | 8.345 | 4.72E−7 | 0.000018 | 6.478 |

| Tceal7 | 2.630 | 3.951 | 9.950 | 4.84E−8 | 0.000004 | 8.833 |

| Tbxas1 | 2.629 | 1.669 | 5.027 | 0.000145 | 0.000985 | 1.131 |

| Cd52 | 2.624 | 3.294 | 6.008 | 0.000023 | 0.000267 | 2.936 |

| Gatm | 2.607 | 2.912 | 9.658 | 7.18E−8 | 0.000005 | 8.239 |

| Ncf1 | 2.604 | 2.865 | 6.010 | 0.000023 | 0.000267 | 2.939 |

| Itgam | 2.575 | 3.015 | 6.901 | 0.000005 | 0.000088 | 4.420 |

| Itgb2 | 2.540 | 3.903 | 7.213 | 0.000003 | 0.000063 | 4.939 |

| Cd74 | 2.495 | 8.595 | 8.088 | 0.000001 | 0.000024 | 6.048 |

| Cotl1 | 2.491 | 4.415 | 7.768 | 0.000001 | 0.000034 | 5.797 |

| Irgm2 | 2.490 | 7.301 | 5.647 | 0.000045 | 0.000420 | 1.871 |

| Fcgr2b | 2.467 | 3.186 | 6.916 | 0.000005 | 0.000087 | 4.460 |

| H2-Eb1 | 2.435 | 7.134 | 8.077 | 0.000001 | 0.000024 | 6.068 |

| Tyrobp | 2.434 | 3.260 | 5.847 | 0.000031 | 0.000327 | 2.649 |

| H2-Ab1 | 2.430 | 7.080 | 7.497 | 0.000002 | 0.000045 | 5.134 |

| Dok2 | 2.422 | 2.595 | 7.234 | 0.000003 | 0.000061 | 4.852 |

| Laptm5 | 2.374 | 5.326 | 8.610 | 3.16E−7 | 0.000014 | 7.016 |

| Arhgap9 | 2.374 | 1.869 | 6.142 | 0.000018 | 0.000225 | 3.005 |

| Mmp19 | 2.351 | 2.135 | 6.825 | 0.000005 | 0.000097 | 4.172 |

| Nabp1 | 2.322 | 3.771 | 8.434 | 4.13E−7 | 0.000017 | 6.777 |

| Coro1a | 2.310 | 4.377 | 6.110 | 0.000019 | 0.000234 | 3.027 |

| Adamts20 | 2.285 | 2.924 | 7.901 | 0.000001 | 0.000029 | 5.848 |

| Igtp | 2.281 | 7.103 | 4.389 | 0.000516 | 0.002535 | −0.614 |

| Myo1g | 2.270 | 3.248 | 5.799 | 0.000034 | 0.000348 | 2.556 |

| Lgals3 | 2.210 | 3.848 | 5.343 | 0.000079 | 0.000639 | 1.659 |

| Cyth4 | 2.203 | 4.035 | 6.760 | 0.000006 | 0.000104 | 4.174 |

| Cidea | 2.199 | 1.385 | 4.490 | 0.000421 | 0.002166 | 0.175 |

| H2-DMa | 2.154 | 3.974 | 6.327 | 0.000013 | 0.000181 | 3.432 |

| Exoc3l4 | 2.143 | 3.013 | 6.319 | 0.000013 | 0.000183 | 3.469 |

| Glipr2 | 2.132 | 2.720 | 5.021 | 0.000147 | 0.000994 | 1.181 |

| B4galnt1 | 2.120 | 3.016 | 5.402 | 0.000071 | 0.000590 | 1.858 |

| Sema4a | 2.059 | 3.510 | 5.431 | 0.000067 | 0.000566 | 1.856 |

| Hmga2-ps1 | 2.052 | 3.692 | 9.446 | 9.61E−8 | 0.000006 | 8.147 |

| Rrm2 | 2.038 | 1.232 | 4.811 | 0.000222 | 0.001349 | 0.683 |

| Naaa | 2.014 | 4.548 | 10.034 | 4.32E−8 | 0.000004 | 9.011 |

| Npr3 | 2.009 | 4.800 | 8.921 | 2.02E−7 | 0.000010 | 7.498 |

| Slc7a5 | 1.999 | 2.188 | 7.039 | 0.000004 | 0.000075 | 4.453 |

| Ift122 | 1.985 | 4.799 | 13.184 | 1.03E−9 | 2.97E−7 | 12.604 |

| Gadd45a | 1.981 | 4.215 | 10.722 | 1.78E−8 | 0.000002 | 9.840 |

| Alox5ap | 1.972 | 2.676 | 6.640 | 0.000007 | 0.000122 | 3.980 |

| Slamf9 | 1.961 | 1.992 | 5.469 | 0.000062 | 0.000534 | 1.965 |

| Lat2 | 1.927 | 2.050 | 5.195 | 0.000105 | 0.000774 | 1.499 |

| Ctnna3 | 1.924 | 2.075 | 7.270 | 0.000003 | 0.000059 | 4.749 |

| Sh3bp2 | 1.920 | 3.485 | 9.571 | 8.08E−8 | 0.000006 | 8.295 |

| Cldn1 | 1.903 | 1.799 | 4.468 | 0.000440 | 0.002234 | 0.168 |

| Psat1 | 1.898 | 1.313 | 4.895 | 0.000188 | 0.001194 | 0.855 |

| Lgmn | 1.834 | 5.827 | 14.434 | 2.88E−10 | 1.33E−7 | 13.935 |

| Fcrls | 1.833 | 1.977 | 7.046 | 0.000004 | 0.000075 | 4.529 |

| Golga7b | 1.811 | 1.738 | 6.437 | 0.000011 | 0.000158 | 3.451 |

| Tubb6 | 1.796 | 4.939 | 11.369 | 8.04E−9 | 0.000001 | 10.667 |

| Grem2 | 1.768 | 2.322 | 4.412 | 0.000493 | 0.002448 | 0.074 |

| AI662270 | 1.745 | 1.018 | 4.196 | 0.000763 | 0.003426 | −0.342 |

| Tfrc | 1.735 | 7.623 | 6.143 | 0.000018 | 0.000225 | 2.734 |

| Spred3 | 1.731 | 2.136 | 4.956 | 0.000167 | 0.001091 | 1.064 |

| Csf2ra | 1.698 | 2.800 | 5.948 | 0.000026 | 0.000287 | 2.833 |

| Cfp | 1.685 | 3.046 | 5.561 | 0.000052 | 0.000472 | 2.141 |

| Hspb8 | 1.666 | 9.033 | 19.284 | 4.43E−12 | 9.51E−9 | 18.041 |

| Aldh18a1 | 1.657 | 2.794 | 7.696 | 0.000001 | 0.000037 | 5.604 |

| Spag5 | 1.641 | 2.592 | 5.839 | 0.000031 | 0.000329 | 2.636 |

| P2ry6 | 1.562 | 2.997 | 7.487 | 0.000002 | 0.000045 | 5.364 |

| Tceal5 | 1.543 | 3.686 | 7.726 | 0.000001 | 0.000036 | 5.747 |

| Ckap4 | 1.536 | 3.968 | 7.761 | 0.000001 | 0.000034 | 5.794 |

| Azin1 | 1.521 | 5.713 | 13.954 | 4.65E−10 | 1.76E−7 | 13.463 |

| Igsf1 | 1.508 | 1.443 | 3.972 | 0.001204 | 0.004901 | −0.732 |

| Pstpip1 | 1.498 | 2.098 | 4.284 | 0.000638 | 0.002969 | −0.186 |

| Stbd1 | 1.486 | 6.666 | 12.548 | 2.06E−9 | 4.58E−7 | 12.006 |

| Cpne2 | 1.483 | 3.586 | 7.274 | 0.000003 | 0.000059 | 5.036 |

| Prkcd | 1.471 | 4.898 | 7.292 | 0.000002 | 0.000057 | 4.962 |

| Ttc9 | 1.466 | 2.723 | 6.072 | 0.000020 | 0.000246 | 3.049 |

| Cmtm7 | 1.459 | 2.701 | 6.566 | 0.000008 | 0.000132 | 3.875 |

| Abca1 | 1.423 | 3.976 | 7.552 | 0.000002 | 0.000042 | 5.463 |

| 1500017E21Rik | 1.409 | 2.067 | 4.084 | 0.000959 | 0.004091 | −0.556 |

| Sdf2l1 | 1.383 | 2.699 | 4.384 | 0.000521 | 0.002555 | −0.004 |

| Sox9 | 1.343 | 2.308 | 3.852 | 0.001539 | 0.005931 | −1.031 |

| Eda2r | 1.343 | 3.579 | 6.014 | 0.000023 | 0.000266 | 2.917 |

| Chrne | 1.326 | 4.528 | 7.848 | 0.000001 | 0.000031 | 5.890 |

| Sap30 | 1.324 | 2.069 | 4.990 | 0.000157 | 0.001039 | 1.130 |

| Cd82 | 1.312 | 3.981 | 5.734 | 0.000038 | 0.000374 | 2.349 |

| Lingo3 | 1.309 | 4.250 | 7.092 | 0.000003 | 0.000072 | 4.677 |

| Tspan9 | 1.296 | 6.328 | 10.313 | 3.01E−8 | 0.000003 | 9.317 |

| Itm2a | 1.292 | 7.355 | 16.163 | 5.72E−11 | 4.72E−8 | 15.550 |

| Mgl2 | 1.266 | 1.953 | 4.786 | 0.000233 | 0.001395 | 0.762 |

| Ehd4 | 1.257 | 6.049 | 10.890 | 1.44E−8 | 0.000002 | 10.070 |

| Igf2 | 1.255 | 4.910 | 7.949 | 0.000001 | 0.000028 | 6.019 |

| Usp18 | 1.254 | 2.133 | 3.780 | 0.001787 | 0.006652 | −1.125 |

| Plp2 | 1.254 | 2.364 | 4.887 | 0.000191 | 0.001209 | 0.928 |

| Ccl11 | 1.246 | 4.434 | 5.570 | 0.000052 | 0.000466 | 1.977 |

| Tnfaip2 | 1.233 | 7.395 | 7.340 | 0.000002 | 0.000054 | 4.850 |

| Plekho1 | 1.202 | 4.896 | 9.497 | 8.95E−8 | 0.000006 | 8.285 |

| Zfp385a | 1.200 | 3.867 | 6.968 | 0.000004 | 0.000082 | 4.505 |

| Dnajb9 | 1.181 | 4.806 | 4.394 | 0.000511 | 0.002517 | −0.310 |

| Lpin2 | 1.176 | 3.086 | 4.394 | 0.000510 | 0.002515 | −0.072 |

| Trp63 | 1.158 | 2.475 | 4.119 | 0.000892 | 0.003864 | −0.517 |

| Ak4 | 1.151 | 3.339 | 5.132 | 0.000119 | 0.000845 | 1.341 |

| Hdgfrp3 | 1.123 | 2.179 | 3.341 | 0.004408 | 0.013353 | −1.975 |

| Tm6sf1 | 1.100 | 3.756 | 4.784 | 0.000235 | 0.001398 | 0.599 |

| Dupd1 | 1.099 | 6.108 | 9.846 | 5.56E−8 | 0.000004 | 8.704 |

| Manf | 1.096 | 4.697 | 5.009 | 0.000151 | 0.001010 | 0.906 |

| Rab13 | 1.078 | 3.415 | 7.078 | 0.000004 | 0.000073 | 4.722 |

| Il12a | 1.070 | 2.516 | 4.863 | 0.000201 | 0.001252 | 0.900 |

| Klhl23 | 1.058 | 5.004 | 9.191 | 1.37E−7 | 0.000008 | 7.864 |

| Rnf144b | 1.045 | 4.943 | 6.328 | 0.000013 | 0.000181 | 3.293 |

| Traf5 | 1.037 | 2.405 | 4.723 | 0.000265 | 0.001529 | 0.632 |

| Tnfrsf12a | 1.014 | 4.028 | 3.003 | 0.008827 | 0.023301 | −3.105 |

| Cmya5 | −1.009 | 11.370 | −14.147 | 3.83E−10 | 1.59E−7 | 13.675 |

| Pdzrn3 | −1.015 | 6.668 | −13.855 | 5.14E−10 | 1.77E−7 | 13.387 |

| 5031425E22Rik | −1.017 | 4.170 | −7.764 | 0.000001 | 0.000034 | 5.778 |

| Jun | −1.032 | 6.645 | −5.072 | 0.000133 | 0.000921 | 0.723 |

| Phc1 | −1.038 | 5.128 | −8.151 | 0.000001 | 0.000022 | 6.307 |

| Gm16576 | −1.039 | 3.886 | −7.731 | 0.000001 | 0.000036 | 5.748 |

| Rab11fip3 | −1.042 | 6.820 | −6.748 | 0.000006 | 0.000106 | 3.847 |

| Cdc42bpg | −1.054 | 4.502 | −7.202 | 0.000003 | 0.000063 | 4.843 |

| Pde4dip | −1.056 | 12.145 | −14.821 | 1.98E−10 | 1.10E−7 | 14.333 |

| Mxi1 | −1.060 | 5.464 | −11.206 | 9.78E−9 | 0.000001 | 10.472 |

| Rassf9 | −1.065 | 1.443 | −3.013 | 0.008655 | 0.022978 | −2.497 |

| Zfp46 | −1.072 | 5.530 | −9.141 | 1.47E−7 | 0.000009 | 7.751 |

| Bhlhe40 | −1.077 | 6.949 | −9.026 | 1.73E−7 | 0.000010 | 7.504 |

| Sptb | −1.089 | 8.512 | −15.098 | 1.52E−10 | 8.89E−8 | 14.596 |

| Mylk2 | −1.091 | 10.840 | −9.401 | 1.02E−7 | 0.000007 | 8.006 |

| Kbtbd13 | −1.093 | 5.106 | −6.439 | 0.000011 | 0.000158 | 3.461 |

| Asb11 | −1.109 | 6.675 | −12.004 | 3.81E−9 | 0.000001 | 11.389 |

| 3425401B19Rik | −1.145 | 9.313 | −10.180 | 3.57E−8 | 0.000003 | 9.082 |

| 9030617O03Rik | −1.167 | 6.026 | −10.513 | 2.32E−8 | 0.000002 | 9.590 |

| Lrrc2 | −1.169 | 6.578 | −9.020 | 1.75E−7 | 0.000010 | 7.516 |

| Pde4b | −1.173 | 6.336 | −9.034 | 1.71E−7 | 0.000010 | 7.544 |

| 5930430L01Rik | −1.178 | 4.912 | −8.802 | 2.39E−7 | 0.000011 | 7.309 |

| Rdh5 | −1.204 | 1.118 | −3.476 | 0.003339 | 0.010802 | −1.629 |

| Gzmm | −1.215 | 2.294 | −4.462 | 0.000446 | 0.002257 | 0.148 |

| Eepd1 | −1.215 | 7.107 | −12.349 | 2.57E−9 | 0.000001 | 11.776 |

| Pmepa1 | −1.254 | 4.264 | −8.047 | 0.000001 | 0.000025 | 6.194 |

| Ptpn3 | −1.262 | 7.902 | −6.847 | 0.000005 | 0.000094 | 3.991 |

| Ccdc3 | −1.272 | 3.630 | −4.364 | 0.000543 | 0.002633 | −0.235 |

| Lmod2 | −1.282 | 6.028 | −4.926 | 0.000177 | 0.001138 | 0.499 |

| Smtnl1 | −1.317 | 5.165 | −7.927 | 0.000001 | 0.000029 | 5.946 |

| Pink1 | −1.327 | 9.709 | −17.549 | 1.75E−11 | 2.24E−8 | 16.724 |

| St3gal2 | −1.349 | 6.560 | −12.569 | 2.02E−9 | 4.58E−7 | 12.029 |

| Zfp503 | −1.360 | 4.275 | −3.801 | 0.001710 | 0.006427 | −1.501 |

| Rilpl1 | −1.362 | 7.695 | −18.020 | 1.18E−11 | 2.08E−8 | 17.080 |

| Cacna2d4 | −1.373 | 5.231 | −8.903 | 2.07E−7 | 0.000010 | 7.430 |

| Cbx7 | −1.385 | 4.726 | −9.928 | 4.98E−8 | 0.000004 | 8.874 |

| Pfas | −1.400 | 4.271 | −10.986 | 1.28E−8 | 0.000002 | 10.179 |

| Foxo4 | −1.413 | 7.602 | −16.257 | 5.26E−11 | 4.72E−8 | 15.635 |

| 4632428C04Rik | −1.440 | 2.156 | −4.199 | 0.000758 | 0.003410 | −0.327 |

| Rps6ka5 | −1.443 | 4.189 | −8.051 | 0.000001 | 0.000025 | 6.234 |

| Myo5c | −1.474 | 4.648 | −8.507 | 3.70E−7 | 0.000015 | 6.887 |

| Uaca | −1.482 | 8.184 | −15.649 | 9.10E−11 | 6.17E−8 | 15.101 |

| Vipr1 | −1.482 | 2.893 | −4.930 | 0.000176 | 0.001134 | 0.972 |

| Klhl34 | −1.513 | 3.932 | −6.159 | 0.000017 | 0.000221 | 3.125 |

| Fam53b | −1.542 | 6.105 | −10.472 | 2.44E−8 | 0.000003 | 9.530 |

| Itgb5 | −1.552 | 6.608 | −12.754 | 1.64E−9 | 4.23E−7 | 12.231 |

| C7 | −1.558 | 2.314 | −4.630 | 0.000318 | 0.001760 | 0.473 |

| Nos1 | −1.562 | 5.242 | −7.618 | 0.000001 | 0.000040 | 5.448 |

| Tbc1d1 | −1.569 | 7.479 | −10.085 | 4.04E−8 | 0.000003 | 8.982 |

| Plcd3 | −1.570 | 3.052 | −6.830 | 0.000005 | 0.000097 | 4.321 |

| Syt3 | −1.593 | 2.118 | −6.079 | 0.000020 | 0.000244 | 3.007 |

| Gpx3 | −1.620 | 7.138 | −12.383 | 2.47E−9 | 0.000001 | 11.814 |

| Pm20d2 | −1.647 | 6.268 | −15.180 | 1.41E−10 | 8.62E−8 | 14.651 |

| Ctxn3 | −1.652 | 1.495 | −4.334 | 0.000576 | 0.002753 | −0.081 |

| Asb2 | −1.668 | 9.342 | −10.236 | 3.31E−8 | 0.000003 | 9.158 |

| Chrna10 | −1.733 | 4.020 | −10.890 | 1.44E−8 | 0.000002 | 10.001 |

| Klhl33 | −1.755 | 6.268 | −10.774 | 1.66E−8 | 0.000002 | 9.922 |

| Otub2 | −1.767 | 3.588 | −5.988 | 0.000024 | 0.000273 | 2.857 |

| Ramp1 | −1.785 | 5.510 | −14.191 | 3.66E−10 | 1.57E−7 | 13.691 |

| Hr | −1.804 | 7.475 | −9.668 | 7.07E−8 | 0.000005 | 8.410 |

| Gadd45b | −1.830 | 4.883 | −14.425 | 2.90E−10 | 1.33E−7 | 13.822 |

| Klhl38 | −1.877 | 5.136 | −12.577 | 1.99E−9 | 4.58E−7 | 12.014 |

| Cyr61 | −1.882 | 5.534 | −13.428 | 7.99E−10 | 2.51E−7 | 12.940 |

| Mpp3 | −2.124 | 5.579 | −14.331 | 3.19E−10 | 1.42E−7 | 13.824 |

| Dusp26 | −2.158 | 5.244 | −16.498 | 4.26E−11 | 4.22E−8 | 15.675 |

| Magix | −2.182 | 5.197 | −15.333 | 1.21E−10 | 7.85E−8 | 14.677 |

| Cyp26b1 | −2.235 | 3.685 | −3.092 | 0.007364 | 0.020209 | −2.582 |

| Odf3l2 | −2.370 | 2.632 | −4.710 | 0.000271 | 0.001561 | 0.617 |

| Art5 | −2.537 | 4.620 | −17.917 | 1.29E−11 | 2.08E−8 | 16.352 |

| Arrdc2 | −2.753 | 4.919 | −3.505 | 0.003146 | 0.010356 | −2.092 |

| Chad | −2.774 | 4.402 | −3.765 | 0.001841 | 0.006801 | −1.503 |

| Mb | −2.906 | 11.623 | −16.590 | 3.93E−11 | 4.22E−8 | 15.929 |

| Inmt | −3.057 | 1.920 | −5.554 | 0.000053 | 0.000473 | 1.988 |

| Tmem100 | −3.134 | 3.007 | −8.309 | 4.98E−7 | 0.000019 | 6.463 |

| Igfn1 | −3.222 | 5.568 | −11.757 | 5.07E−9 | 0.000001 | 11.122 |

| Ddah1 | −3.298 | 3.378 | −9.734 | 6.47E−8 | 0.000005 | 8.317 |

| Chac1 | −4.229 | 4.642 | −6.932 | 0.000005 | 0.000086 | 4.488 |

| Dkk3 | −4.248 | 5.061 | −20.180 | 2.28E−12 | 5.96E−9 | 17.545 |

| Mss51 | −5.383 | 4.941 | −17.550 | 1.74E−11 | 2.24E−8 | 15.348 |

| Prima1 | −5.813 | 1.693 | −7.080 | 0.000004 | 0.000073 | 2.960 |

Finally, because our results indicated that Smad1/5 activation is necessary for the large increase in mass observed when all Smad2/3-activating ligands are inhibited, we examined the expression of selected genes in muscles treated with activin/myostatin prodomains and Smad6. Interestingly, Smad6 actually enhanced the prodomain-mediated increase in Actc1 expression and had no effect on prodomain-mediated suppression of Klhl38 and Igfn1 (Fig. S2B). A transcriptomic analysis of muscles treated with prodomains and Smad6 is likely required to identify the gene targets involved in the Smad1/5 hypertrophy response.

Inhibition of Smad2/3-Activating Ligands Increases Muscle Mass in Dystrophic Mice, but Has Modest Effects on Fibrosis.

Given the progressive increase in muscle mass in WT mice as each additional Smad2/3-activating ligand was inhibited (Fig. 1), we sought to assess whether similar changes could be induced in muscles that exhibit features of dystrophy. Accordingly, the TA muscles of dystrophin-null mice (mdx) and dystrophin-null mice also rendered heterozygous for the homolog, utrophin (het), were injected with AAV vectors encoding prodomains for activin B and/or myostatin. Eight weeks after AAV injection, inhibition of activin A and B with the activin B prodomain increased muscle mass in both dystrophic phenotypes (Fig. 2 A and B) to a similar extent as was observed in WT mice (∼20%). Interestingly, the myostatin prodomain was less potent in the dystrophic setting than in WT mice, increasing muscle mass only 27% in mdx mice and 20% in het mice (Fig. 2 A and B). A synergistic hypertrophic response was observed in the TA muscles of mdx mice when myostatin and activins were inhibited (Fig. 2A) although the magnitude of effect was approximately half that observed in WT mice (Fig. 1A). In het mice, coadministration of the activin B and myostatin prodomains resulted in an additive, rather than synergistic, increase in muscle mass (Fig. 2B). Histological examination revealed that the increase in muscle mass in mdx and het mice was a product of muscle fiber hypertrophy (Fig. 2C), as demonstrated by increases in fiber diameter (Fig. 2D). Expression of the activin B and myostatin prodomains in either dystrophic strain when examined 8 wk after AAV injection was greatly diminished in comparison with the high expression achieved in WT mice (Fig. 2E). Others have implicated cycles of muscle degeneration/regeneration and oxidative stress in the dystrophic mice as contributing to reduced transgene expression in dystrophic muscles (27, 28). Despite reduced prodomain expression in dystrophic muscles at endpoint, initial prodomain expression and the subsequent inhibition of Smad2/3-activating ligands were sufficient to induce TA muscle hypertrophy and maintain suppression of the atrophy-related gene, Igfn1 (Fig. 2F).

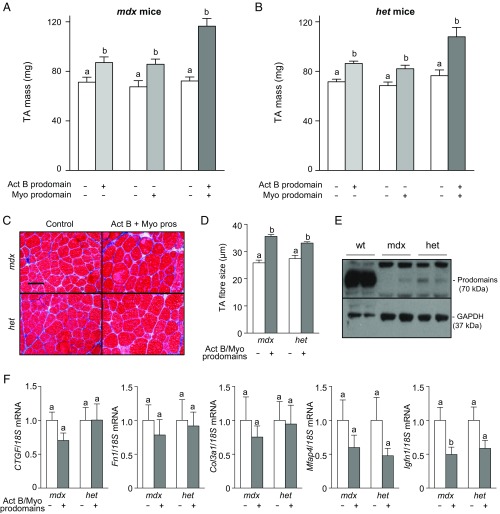

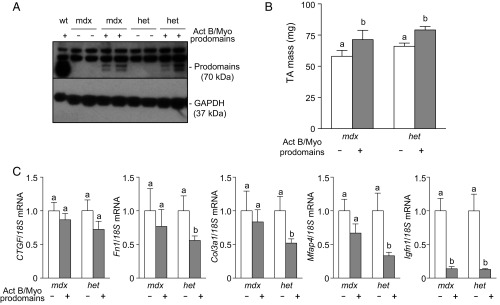

Fig. 2.

The effects of inhibiting Smad2/3-activating ligands in dystrophic mice. The right tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of 4- to 6-wk-old male and female C57BL/6 dystrophin−/− mice (mdx) and dystrophin−/−/utrophin+/− mice (het) were injected with AAV vectors encoding for the modified activin B prodomain and/or the myostatin prodomain (left TA muscles were injected with equivalent doses of empty AAV). (A and B) Eight weeks post-AAV injection, the TA muscles were harvested and weighed (n = 5–10, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (C) Masson’s trichrome staining of TA muscles was performed on cryosections. (Scale bar: 100 µm.) (D) Muscle fiber size quantified (n = 3, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05; at least 150 myofibers were counted per TA muscle). (E) Despite increases in muscle mass with AAV injection, Western blot analysis indicated that there was very little prodomain expression by the experimental endpoint. (F) qRT-PCR analysis of fibrosis and atrophy genes CTGF, Fn1, Col3a1, Mfap4, and Igfn1 in the presence or absence of Smad2/3 signaling (n = 4–8, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05).

Although myofiber size was increased after treatment of the muscles of mdx and het mice, further histological analysis of the prodomain-treated TA muscles revealed the persistence of fibrotic connective tissue and centrally located nuclei, both of which are characteristic hallmarks of dystrophic pathology (Fig. 2C). Consistent with the histological observations, transcriptional analysis confirmed that typical markers of fibrosis, CTGF, Fn1, Col3a1, and Mfap4, were increased in the TA muscles of mdx and het mice (Fig. S3A) and were not decreased 8 wk after administration of prodomain vectors (Fig. 2F). Considering the possibility that persistent, rather than transient, suppression of Smad2/3-activating ligands was required to improve the dystrophic phenotype in these animals, we repeated the study but examined the mass and histology of TA muscles 2 wk after vector administration, when prodomain expression was still evident (Fig. 3A). Even at this early time point, prodomains significantly increased TA muscle mass in both mdx and het mice (Fig. 3B). Histological analysis did not conclusively indicate that fibrosis within the muscles of these mice was reduced after overexpression of activin and myostatin prodomains for 2 wk. However, the expression of fibrosis genes Fn1, Col3a1, and Mfap4 was significantly reduced by prodomains in het mice, and there was a trend for a decrease in expression of these genes in mdx mice (Fig. 3C). The major reduction in Igfn1 expression observed 2 wk after vector administration confirmed the activity of the overexpressed prodomains in both mouse strains (Fig. 3C). Thus, inhibition of Smad2/3-activating ligands seems sufficient to increase mass and reduce fibrosis in muscles of dystrophic mice.

Fig. S3.

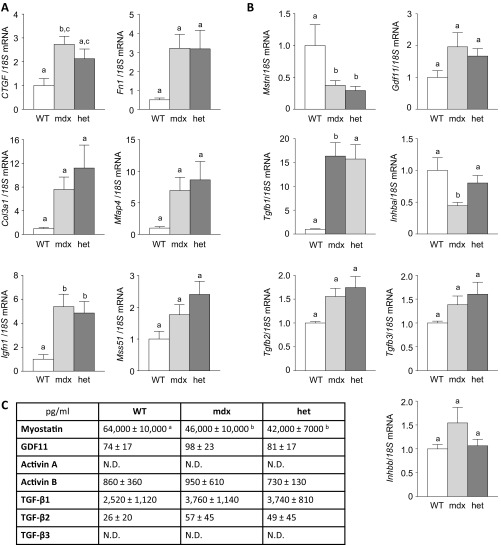

Skeletal muscle expression of fibrosis- and atrophy-associated genes and circulating levels of TGF-β proteins in WT and dystrophic mice. qRT-PCR analysis was used to assess mRNA expression of (A) fibrosis (CTGF, Fn1, Col3a1, and Mfap4) and atrophy (Igfn1 and Mss51) associated genes, and (B) TGF-β superfamily genes (Mstn, Gdf11, Inhba, Inhbb, Tgfb1, Tgfb2, and Tgfb3) in TA muscles of WT, mdx, and het mice. For the TGF-β genes, prodomains had no effects on expression. (C) Specific ELISAs were used to measure circulating TGF-β levels (all experiments, n = 5–6, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05; N.D., not detected).

Fig. 3.

Persistent inhibition of Smad2/3 activating ligands increases mass and reduces fibrosis in muscles of dystrophic mice. The right tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of 4- to 9-wk-old male and female C57BL/6 dystrophin−/− mice (mdx) and dystrophin−/−/utrophin+/− mice (het) were injected with AAVs encoding for the activin B and myostatin prodomains (left TA muscles were injected with equivalent doses of empty AAV). (A) Western blot analysis indicated the continued expression of prodomains 2 wk post-AAV injection. (B) TA muscles were harvested and weighed (n = 5–10, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (C) qRT-PCR analysis of fibrosis and atrophy genes CTGF, Fn1, Col3a1, Mfap4, and Igfn1 in the presence or absence of Smad2/3 signaling (n = 4–8, paired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05).

To extend these findings, we performed qRT-PCR for Mstn, Gdf11, Inhba (codes for activin A), Inhbb (codes for activin B), Tgfb1, Tgfb2, and Tgfb3 in skeletal muscle of WT, mdx, and het mice treated with, or without, prodomains. Interestingly, Mstn mRNA levels decreased significantly in dystrophic mice whereas Gdf11 (2.5-fold), Tgfb1 (18-fold), Tgfb2 (1.7-fold), Tgfb3 (1.7-fold), and Inhbb (∼twofold) mRNA levels increased (Fig. S3B). Similar changes were observed in circulating levels of these seven TGF-β proteins, with serum myostatin levels significantly decreased in dystrophic mice (WT, 64 ± 10 ng/mL; mdx, 46 ± 10 ng/mL; het, 42 ± 7 ng/mL, n = 6) whereas serum TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and GDF11 levels showed a trend toward increase (Fig. S3C). Thus, fibrosis in mdx and het mice occurs despite decreased local and circulating levels of myostatin and is likely due to increased expression of other TGF-β ligands, particularly TGF-β1. How specific activin and myostatin inhibitors reduce fibrosis in this setting (Fig. 3C) remains to be determined but may result from a reduction in the net tone of pSmad2/3 levels within dystrophic muscles.

Inhibition of Smad2/3-Activating Ligands Prevents Local Muscle Wasting in the Colon-26 Model of Cancer Cachexia.

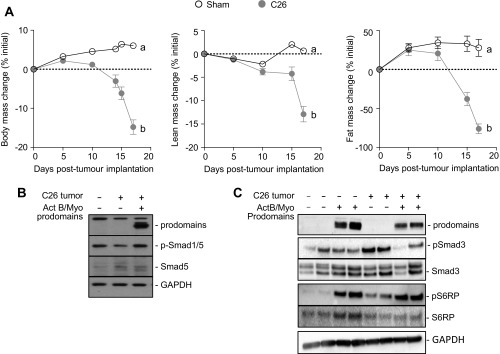

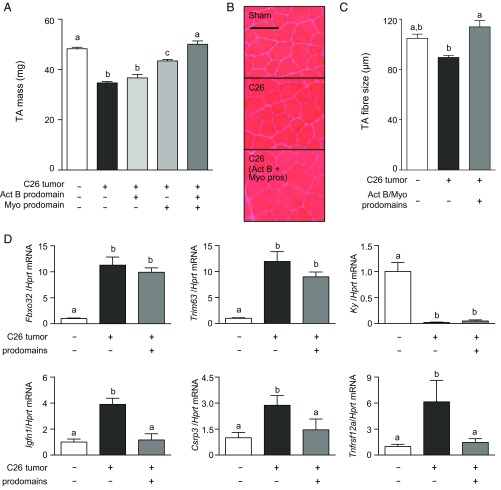

Mice bearing colon-26 (C26) tumors develop severe cachexia, characterized by a rapid loss of lean and fat mass (Fig. S4A). Because activins and myostatin have been strongly associated with the pathogenesis of cachexia in mice bearing C26 tumors (29, 30), we examined whether prodomain treatment could prevent muscle wasting in this model. C26 tumor fragments were implanted s.c. into male BALB/c mice, and, simultaneously, the TA muscles were injected with AAV vectors encoding for myostatin and/or activin B prodomains. At the experimental endpoint (18 d), the TA muscles of C26 tumor-bearing mice exhibited a 28% reduction in mass compared with muscles of sham mice (Fig. 4A). Although specific inhibition of activin A and B within the TA muscle had no effect, blocking myostatin partially reversed C26 tumor-induced wasting (Fig. 4A). Importantly, inhibiting myostatin and activins not only prevented muscle wasting in the C26 model but also led to a small increase (4%) in muscle mass, compared with sham mice (Fig. 4A). Histological examination revealed that the decrease in muscle mass in C26 tumor-bearing mice was a product of muscle fiber atrophy (Fig. 4B), as demonstrated by decreases in fiber diameter (Fig. 4C), and that these changes were reversed after codelivery of the activin B and myostatin prodomains. By Western blot, there was a decrease in the activation of the growth promoting Smad1/5 pathway in cachectic muscles, but this decrease was reversed after prodomain treatment (Fig. S4B).

Fig. S4.

Catabolic effects of C26 tumors in mice. C26 tumor fragments were implanted s.c. into 8- to 10-wk-old male BALB/c mice, and simultaneously the TA muscles were injected with AAVs encoding for activin B and/or myostatin prodomains (control mice received sham surgery and injection of equivalent doses of empty AAV). (A) Body weights were assessed and lean and fat masses measured by EchoMRI analysis and plotted as percentage change from the day of tumor implantation (n = 14–16, unpaired Student’s t test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (B and C) Western blot analysis was used to assess prodomain expression and the phosphorylation of Smad1/5, Smad2/3, and S6RP.

Fig. 4.

Prevention of local muscle wasting in colon-26 tumor-bearing mice by inhibition of Smad2/3-activating ligands. C26 tumor fragments were implanted s.c. into 8- to 10-wk-old male BALB/c mice, and simultaneously the TA muscles were injected with AAVs encoding for activin B and/or myostatin prodomains (control mice received sham surgery and injection of equivalent doses of empty AAV). (A) After 18 d, when C26 tumor-bearing mice required euthanasia, TA muscles were harvested and weighed (n = 6–16, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining on TA muscles was performed on cryosections of sham, cachectic, and activin B plus myostatin prodomain-treated mice. (Scale bar: 100 µm.) (C) Muscle fiber size quantified (n = 3, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05; at least 150 myofibers were counted per TA muscle). (D) qRT-PCR analysis was used to assess mRNA expression of Fbxo32, Trim63, Ky, Igfn1, Csrp3, and Tnfrsf12a (n = 5, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, data groups with different letters achieved significance of P < 0.05).

Mechanistically, factors produced by the C26 tumors increased mRNA expression of atrophy-related genes, including Tnfrsf12a, Igfn1, Csrp3, and the muscle specific E3 ubiquitin ligases Fbxo32 and Trim63 (Fig. 4D). In addition, Ky, a gene implicated in muscle hypertrophy (31, 32), was markedly down-regulated in C26 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4D). Inhibition of myostatin and activins decreased expression of Tnfrsf12a, Igfn1, and Csrp3 to control levels, indicating that these genes are under Smad2/3 control in mice bearing C26 tumors (Fig. 4D). In contrast, elevated expression of Fbxo32 and Trim63 and decreased expression of Ky were unaltered after inhibition of Smad2/3-activating ligands. That the activin B and myostatin prodomains prevented TA muscle wasting in the presence of persistently elevated levels (>10-fold) of Fbxo32 and Trim63 is unexpected, and it indicates that inhibition of the Smad2/3 pathway can counteract the catabolic effects of these ubiquitin ligases (Fig. 4D). This counteractivity may be due to the ability of the prodomains to drive skeletal muscle protein synthesis, in a similar manner to follistatin (19), even in mice bearing C26 tumors (Fig. S4C).

Discussion

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) network of ligands and intracellular signaling proteins is the subject of intense interest within the field of skeletal muscle biology (24). Although specific TGF-β family members have been investigated extensively as negative regulators of growth and have been designated as targets for the development of therapeutics to combat muscle-related diseases, emerging roles for other ligands (22, 23) are prompting deeper investigation of the myriad ways this network controls skeletal muscle attributes in health and disease.

Most focus has centered on the Smad2/3-activating ligand myostatin as the major negative regulator of muscle growth (1). In the present study, inhibition of myostatin (and, potentially, the closely related ligand GDF11) in TA muscles of WT mice resulted in a 45% increase in mass, a finding consistent with earlier studies (11, 12). Although substantial, this degree of hypertrophy is considerably less than has been reported after treatment with broad-spectrum TGF-β antagonists, such as follistatin (20). Consequently, we examined the contribution of activins to the negative regulation of muscle growth. Although not expressed at high levels in skeletal muscle, inhibition of circulating activin A and activin B induced modest (∼20%) increases in muscle mass. However, inhibition of myostatin and activins resulted in a surprising synergistic hypertrophic response, with muscle mass increasing >150%. These findings indicate that Smad2/3 signaling must be completely inhibited within skeletal muscle to promote maximal hypertrophy. Even the low level of Smad2/3 activation in muscle that is induced by circulating activin A and B is sufficient to limit growth after myostatin blockade. In support, only 44 and 181 genes were significantly regulated by activin B prodomain or myostatin prodomain treatment, respectively, whereas, in combination, these prodomains altered the expression of 3,849 genes. These observations demonstrate how targeting distinct ActRIIB ligands influences processes in skeletal muscle and that joint targeting can exert significantly greater impact upon gene regulation.

Activation of the protein synthesis pathway seemed to be a primary mechanism underlying the observed hypertrophy. Phosphorylation of effector molecules in the insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-stimulated protein synthesis pathway, mTOR and S6RP, was significantly enhanced after combined activin B and myostatin prodomain treatment. In addition, RNA-Seq showed that complete inhibition of Smad2/3 signaling in muscle resulted in markedly increased expression of growth factor (Igf2, increased 2.4-fold), amino acid transport (Slc7a5, fourfold; Lat2, 3.8-fold), and amino acid biosynthesis (Psat1, 3.7-fold) genes critical for protein synthesis (33–35). In terms of protein degradation, the expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligases Fbxo32 (MAFbx/atrogin1), Trim63 (MuRF1), and Fbxo30 (Musa1) (7, 22), which classically drive this pathway in muscle, was not substantially reduced after 8 wk of myostatin/activin blockade. However, in our analysis of genes regulated by both prodomain and follistatin (26) treatment, we observed down-regulation of members of the ankyrin repeat and SOCS box family (Asb2 and Asb11), as well as multiple Kelch-like proteins (Klhl33, Klhl34, Klhl38, and Kbtbd13). These genes encode substrate recognition/adaptor subunits of Cullin-based ubiquitin ligases and are involved in ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Importantly, we have previously shown that Asb2 is a negative regulator of muscle mass (26) whereas Asb11 plays a key role in embryonic, as well as adult, regenerative myogenesis (36), and mutations in Kbtbd13 are associated with nemaline myopathy (37). Studies are needed to consider how down-regulation of this group of genes after complete inhibition of Smad2/3 signaling affects protein degradation pathways in muscle.

One of the most compelling themes to emerge in skeletal muscle biology recently is the positive role of the BMP-Smad1/5 axis on growth (22, 23). Normally, Smad1/5 signaling is low in skeletal muscle, and inhibition of this pathway with Smad6 has no effect on mass. However, Smad1/5 signaling is initiated upon myostatin and activin blockade, and this pathway drives the observed synergistic hypertrophic response. Thus, the BMP axis becomes an important positive regulator of muscle mass in the absence of a Smad2/3 signal. Our current model to explain this phenomenon is that sequestration of myostatin and activin isoforms by modified prodomains enables endogenous BMPs to engage activin type II receptors (ActRIIA/IIB), for which they normally display low affinity (38). Which endogenous BMPs are involved in this process is an open question; however, RNA-Seq data indicate that BMP5 and BMP6 are the most highly expressed members of the subfamily within muscle.

Inhibition of myostatin-related ligands in mouse models of muscular dystrophy has been shown variously to reduce muscle fibrosis and increase mass and strength although side effects, including increased susceptibility to fatigue with continued activation, may occur (39). Recently, a phase 1/2a follistatin gene therapy trial was completed in Becker muscular dystrophy patients, with encouraging results showing muscle hypertrophy, reduced endomysial fibrosis, reduced central nucleation, and improved distances walked in a 6-min test (40). In this study, we examined the relative contribution of myostatin and activin isoforms to dystrophic pathophysiology. In mdx and het mice, inhibiting activins increased muscle mass to the same extent as inhibiting myostatin (∼20%). Although myostatin expression is reported to increase in mdx muscles (41), we actually observed a significant decrease in local and circulating levels of this growth factor, which may contribute to its reduced role in negatively regulating mass in the dystrophic setting. As observed in WT mice, a synergistic increase in mass was observed when myostatin and activins were inhibited in the TA muscles of mdx mice for 8 wk; however, there was no corresponding reduction in the degree of fibrosis. We noted that prodomain expression was lost by 8 wk after vector delivery (likely due to increased fiber turnover in dystrophic muscles), and, therefore, we repeated the study for a shorter period. Constant Smad2/3 inhibition for 2 wk both ameliorated fibrosis and increased muscle mass, supporting the consideration of reagents such as follistatin or modified prodomains for the treatment of muscular dystrophy.

Smad2/3-activating ligands are also closely associated with the pathogenesis of the severe wasting syndrome, cancer cachexia (2, 29, 30). We have previously shown that increased circulating activins contribute to lean tissue loss in a number of cachexia models and that intracellular inhibition of Smad signaling, after gene delivery of the inhibitor Smad7, prevents muscle wasting associated with cachexia (42). In this study, we compared the therapeutic potential of the activin B and myostatin prodomains, alone and together, in the colon-26 (C26) model of cachexia (43). Inhibiting activins did not limit TA muscle wasting in C26 tumor-bearing mice, perhaps reflecting inadequate prodomain production to cope with the progressively increasing levels of tumor-derived activins. In contrast, blocking local myostatin signaling in mice carrying C26 tumors partially reversed muscle wasting. Inhibiting all four TGF-β ligands completely blocked wasting in the treated TA muscle but did not induce the same hypertrophic response as observed in WT and dystrophic mice. Transcriptional analysis indicated that expression of E3 ubiquitin ligases involved in protein degradation (Fbxo32 and Trim63) was markedly elevated in C26 tumor-bearing mice and was not affected by prodomain treatment. That prodomains could block muscle wasting, despite persistently activated protein degradation pathways, likely reflects the positive effects of Smad2/3 inhibition on protein synthesis.

In conclusion, using specific antagonists, we have determined the relative contribution of Smad2/3-activating ligands to the negative regulation of muscle mass and confirmed the importance of the BMP-Smad1/5 axis in promoting growth. These findings provide the framework for more precise regulation of the TGF-β signaling network to reverse muscle wasting associated with disease.

Materials and Methods

Production of AAV Vectors.

Generation of the modified activin A and B prodomains has been previously described (21). For modifying the myostatin prodomain, QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis was used to substitute an alanine for aspartate at residue 99 to remove the BMP-1 cleavage site. A FLAG-tag was also introduced at the C-terminal domain by overlap-extension PCR. This modified FLAG-tagged myostatin prodomain was subsequently fused to the Fc-domains of a class IgG2A mouse antibody by overlap-extension PCR. The cDNA constructs encoding for modified activin A, activin B, and myostatin prodomains were then cloned into an AAV expression plasmid consisting of a CMV promoter/enhancer and SV40 poly-A region flanked by AAV2 terminal repeats. These AAV plasmids were cotransfected with pDGM6 packaging plasmid into HEK-293 cells to generate type-6 pseudotyped viral vectors, which were then harvested and purified as described previously (44). HEK-293 cells were seeded onto culture plates for 8 to 16 h before transfection. Plates were transfected with a vector genome-containing plasmid and the packaging/helper plasmid pDGM6 by calcium phosphate precipitation (44). After 72 h, the media and cells were collected and subjected to three cycles of freeze–thaw, followed by 0.22-µm clarification (Millipore). Vectors were purified from the clarified lysate by affinity chromatography using heparin columns (HiTrap; GE Healthcare), the eluent was ultracentrifuged overnight, and the vector-enriched pellet was resuspended in sterile physiological Ringer's solution. The purified vector preparations were quantified with a customized sequence-specific quantitative PCR-based reaction (Life Technologies) (44).

Animal Experiments.

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes (National Health & Medical Council of Australia, 2016). Studies involving the use of research animals were approved by the Alfred Medical Research and Education Precinct Animal Ethics Committee (AMREP AEC). For experiments in WT mice, vectors carrying transgenes of modified prodomains were injected into the right tibialis anterior (TA) muscle of 6- to 8-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice under isoflurane anesthesia at the following optimal concentrations for transgene expression: activin A prodomain [1010 vector genomes (vg)], activin B prodomain (1010 vg), myostatin prodomain (5 × 1010 vg), and Smad6 (2.5 × 109 vg). As controls, the left TA muscles were injected with AAVs carrying an empty vector at equivalent doses. In dystrophic mice (mdx, dystrophin−/− and het, dystrophin−/−:utrophin+/−), 4- to 9-wk-old males and females were injected with vectors carrying transgenes of modified prodomains at the same doses as the WT mice. At the experimental endpoint, mice were humanely euthanized via cervical dislocation, and TA muscles were excised rapidly and weighed before subsequent processing.

Implantation of colon-26 (C26)-derived tumor tissue was carried out on isoflurane-anesthetized 8- to 10-wk-old male BALB/c mice, as described previously (45). Briefly, tumor pieces were thawed from liquid nitrogen, and 1-mm3 pieces were then implanted using a trocar needle through a small incision beneath the skin overlaying the flank. Vectors carrying transgenes of modified prodomains were injected at the same doses as described above. Mice were analyzed for body mass and composition using quantitative magnetic resonance (EchoMRI) performed periodically during the 3-wk experiment. At the experimental endpoint, terminal blood samples were collected from anesthetized mice by cardiac puncture, and mice were then humanely euthanized via cervical dislocation, and muscles were excised rapidly and weighed before subsequent processing.

Histology.

Harvested muscles were placed in OCT cryoprotectant and frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane. The frozen samples were cryosectioned at 10-µm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Masson's Trichrome, as described previously (29). All sections were mounted using DePeX mounting medium (VWR) and imaged at room temperature using a U-TV1X-2 camera mounted to an IX71 microscope, and an Olympus PlanC 10×/0.25 objective lens. DP2-BSW acquisition software (Olympus) was used to acquire images. The minimum Feret’s diameter of muscle fibers was determined using ImageJ software (US National Institutes of Health) by measuring at least 150 fibers per mouse muscle.

Transcriptome Sequencing and Bioinformatics.

Whole transcriptome sequencing (mRNA-Seq) was performed on TA muscles injected with empty AAV, AAV:Activin B prodomain, AAV:Myostatin prodomain, or a combination of AAV vectors expressing both prodomains. Integrity of RNA was determined using the Agilent Bioanalyzer, and all samples gave RNA integrity number (RIN) scores of ≥8.8. One microgram of total RNA was processed using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep kit (Illumina) to generate indexed cDNA libraries for each RNA sample. Libraries were verified by Bioanalyzer and quantitated by qPCR. A single equimolar pool was prepared and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq3000, with the resulting 50-bp single-end reads mapped to the mouse genome (mm10) using STAR software (46). Gene expression data were analyzed by Limma (47), and GO analyses of molecular function were analyzed using the bioinformatics resource DAVID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH) (48).

qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was collected from muscles using TRIzol (Life Technologies). RNA (1 to 3 μg) was reverse transcribed using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Life Technologies). Gene expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR, with Hprt or 18S to standardize cDNA concentrations, using TaqMan gene expression assays (Life Technologies) and ABI detection software. Data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method of analysis and normalized to a control value of 1.

Western Blotting.

TA muscles were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA)-based lysis buffer (Millipore) supplemented with Phosphatase and Protease Inhibitor Mixtures (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and then denatured for 5 min at 95 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using a protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Protein fractions were subsequently separated by SDS/PAGE using precast 4 to 12% Bis-Tris gels (Bio-Rad) blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies against FLAG (for prodomain expression), Smad6, p-mTOR, mTOR, p-S6RP, S6RP, p-Smad1/5, Smad1/5, p-Smad3, or Smad3 (Cell Signaling Technologies) at 1:1,000 dilution, or GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:10,000 as described previously (46), and then probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. Chemiluminescence was detected using ECL Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare). Quantification of labeled Western blots was performed using ImageJ pixel analysis. Densitometric analyses of Western blots are presented as band density and normalized to the control value of 1.

ELISAs.

Specific ELISAs used to measure circulating TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3, Myostatin, and GDF11 were purchased from R&D Systems whereas the activin B assay was from AnshLabs. Activin A levels were measured using an in-house assay, as previously described (29).

Myostatin Prodomain Activity.