Significance

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are far from being only an inevitable byproduct of respiration. They are instead actively generated by NADPH oxidases (NOXs), a family of highly regulated enzymes that underpin complex functions in the control of cell proliferation and antibacterial defense. By investigating the individual catalytic domains, we elucidate the core of the NOX 3D structure. An array of cofactors is spatially organized to transfer reducing electrons from the intracellular milieu to the ROS-generating site, exposed to the outer side of the cell membrane. This redox chain is finely tuned by structural elements that cooperate to control NADPH binding, thereby preventing noxious spills of ROS. Our findings indicate avenues for the pharmacological manipulation of NOX activity.

Keywords: membrane protein, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, redox biology, NOX

Abstract

NADPH oxidases (NOXs) are the only enzymes exclusively dedicated to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Dysregulation of these polytopic membrane proteins impacts the redox signaling cascades that control cell proliferation and death. We describe the atomic crystal structures of the catalytic flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)- and heme-binding domains of Cylindrospermum stagnale NOX5. The two domains form the core subunit that is common to all seven members of the NOX family. The domain structures were then docked in silico to provide a generic model for the NOX family. A linear arrangement of cofactors (NADPH, FAD, and two membrane-embedded heme moieties) injects electrons from the intracellular side across the membrane to a specific oxygen-binding cavity on the extracytoplasmic side. The overall spatial organization of critical interactions is revealed between the intracellular loops on the transmembrane domain and the NADPH-oxidizing dehydrogenase domain. In particular, the C terminus functions as a toggle switch, which affects access of the NADPH substrate to the enzyme. The essence of this mechanistic model is that the regulatory cues conformationally gate NADPH-binding, implicitly providing a handle for activating/deactivating the very first step in the redox chain. Such insight provides a framework to the discovery of much needed drugs that selectively target the distinct members of the NOX family and interfere with ROS signaling.

The NADPH-oxidases (NOXs) form the only known enzyme family whose sole function is reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (1, 2). Initially described in mammalian phagocytes and called phagocyte oxidases, NOXs were shown to function as “bacterial killers” through the production of bactericidal oxygen species using molecular oxygen and NADPH as substrates. The importance of the phagocyte oxidase (now known as NOX2) in host defense was demonstrated by the severe infections that occur in patients affected by chronic granulomatous disease, in which the phagocytes suffer by inefficient superoxide-producing NOX activities (3). After this initial discovery, it was found that mammals contain several enzyme isoforms: NOX1–5 and Duox1–2, which differ with respect to their specific activities and tissue distribution (2). Each of these seven human NOXs is finely regulated by protein–protein interactions and signaling molecules to be activated only after the proper physiological stimuli. Consistently, NOXs are typically associated to cytosolic protein partners, which can switch on/off the oxidase activity. It has now become clear that NOXs primarily function as key players in cell differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis (4–8). Of note, oncogene expression has been widely reported to depend upon ROS production to exert its mitogenic effects and NOX1/4 are emerging as attractive targets for anticancer chemo-therapeutics (9–11). Pharmacological intervention on NOXs, which is intensively sought against inflammatory and oncology diseases, is currently hampered by the lack of selective drugs (12).

NOXs are membrane proteins that share the same catalytic core: a six transmembrane helical domain (TM) and a C-terminal cytosolic dehydrogenase domain (DH). DH contains the binding sites for FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide) and NADPH, whereas TM binds two hemes (1, 2, 13). The enzyme catalytic cycle entails a series of steps, which sequentially transfer electrons from cytosolic NADPH to an oxygen-reducing center located on the extracytoplasmic side of the membrane (hereafter referred to as the “outer side”). Thus, a distinctive feature of NOXs is that NADPH oxidation and ROS production take place on the opposite sides of the membrane (1, 2). The main obstacle to the structural and mechanistic investigation of NOX’s catalysis and regulation has been the difficulty encountered with obtaining well-behaved proteins in sufficient amounts. In fact, the overexpression of NOXs is often toxic to cells, with consequent loss of biomass and final protein yield. Moreover, upon extraction from the membranes, these enzymes tend to proteolyze spontaneously and lose their noncovalently bound cofactors (FAD and hemes). Therefore, a different approach had to be devised to achieve a crystallizable protein. We reasoned that the single-subunit NOX5 could be an attractive system for structural studies because it does not require accessory proteins for its function, which is instead regulated by an N-terminal calcium-binding EF-hand domain (Fig. S1A) (14, 15). Several eukaryotic and prokaryotic NOX5 orthologs were investigated for recombinant protein expression and stability. We found Cylindrospermum stagnale NOX5 (csNOX5) to be promising for structural studies. csNOX5 bears a very significant 40% sequence identity to human NOX5 and was likely acquired by cyanobacteria through gene transfer from a higher eukaryote (Fig. S1B) (14). To overcome proteolysis issues presented by the full-length csNOX5, we adopted a “divide and conquer” approach and proceeded to work on the individual domains. Here, we describe crystal structures of DH and TM, forming the catalytic core common to the whole NOX family. We also describe a mutation of the cytosolic DH that drastically increases its stability in solution and was key to crystallize it. The structural analysis, supported by kinetics and mutagenesis data, presented herein, reveals in unprecedented detail the mechanisms of electron transfer and dioxygen reduction. This structural model considerably advances our understanding of the conformational changes and molecular interactions that orchestrate NOX regulation.

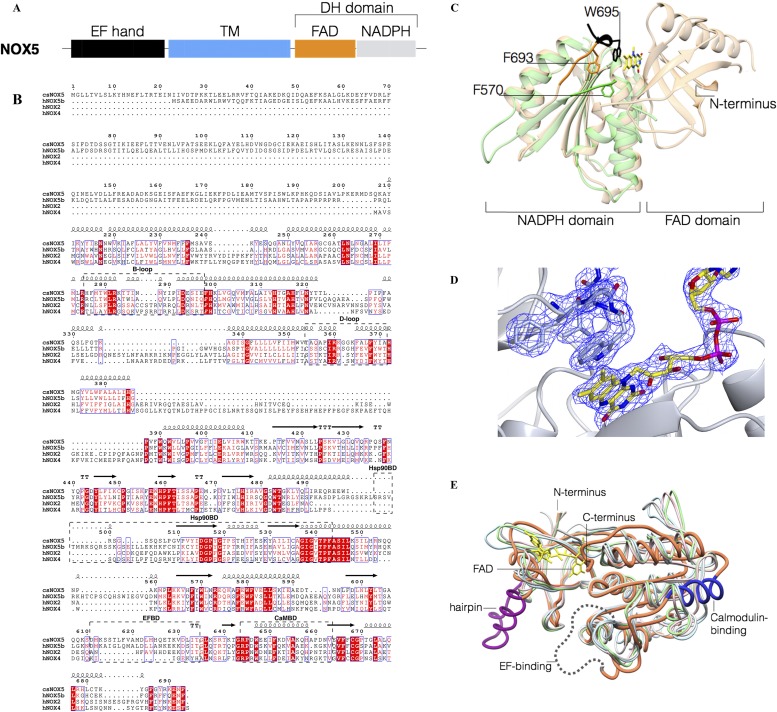

Fig. S1.

Sequence and structural alignments of NOXs. (A) Schematic representation of the domain organization of NOX5. (B) Alignment of representative NOX sequences (human NOX2, human NOX4, human NOX5, and C. stagnale NOX5). Functionally relevant segments are boxed. CAMBD, calmodulin-binding region; EFBD, binding site for the EF-hand domain; HSP90BD, HSP90-binding region. Secondary structure segments, gathered from the csDH and csTM crystal structures, are indicated. Produced with ESPrit. (C) Structural superposition between the NADPH-binding lobe of human NOX2 (PDB ID code 3A1F) and the DH domain of csNOX5. Human NOX2 is in green and csNOX5-DH in light orange (44% sequence identity, rmsd of 1.4 Å for the superposed Cα atoms). There is a large shift in the position of the C-terminal residues (e.g., 7.9 Å between the Cα of Phe570 of human NOX2 and Phe693 of csNOX5, whose side chains are shown as reference). The additional PW695LEL of mutant csDH is in black (Trp695 side chain is shown as reference). (D) Final weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density map for the PW695LEL C-terminal residues and the FAD. The contour level is 1.3 σ. (E) Superposition of csDH with ferredoxin-NADP oxidoreductase enzymes. csDH is depicted in orange with the calmodulin-binding region in blue (R644-V663) (see B), the unstructured EF-hand binding loop in dotted gray (D611-T634), and the protruding hairpin of the FAD-binding lobe in purple (Q489-G509). Ferredoxin reductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus is in light blue (PDB ID code 2VNK, 17% identity with csDH, rmsd of 2.4 Å for 257 Cα atoms), ferredoxin-NADP reductase from Salmonella typhimurium in light green (PDB ID code 3FPK, 16%, 2.4 Å, 247 Cαs), flavodoxin reductase from E. coli in pink (PDB ID code 1FDR, 16%, rmsd 2.3 Å, 244 Cαs), ferredoxin oxidoreductase from Azotobacter vinelandii in light gray (PDB ID code 1A8P, 14%, 2.6 Å, 257 Cαs).

Results and Discussion

A Hyperstabilizing Mutation Enabled the Structural Elucidation of NOX’s DH Domain.

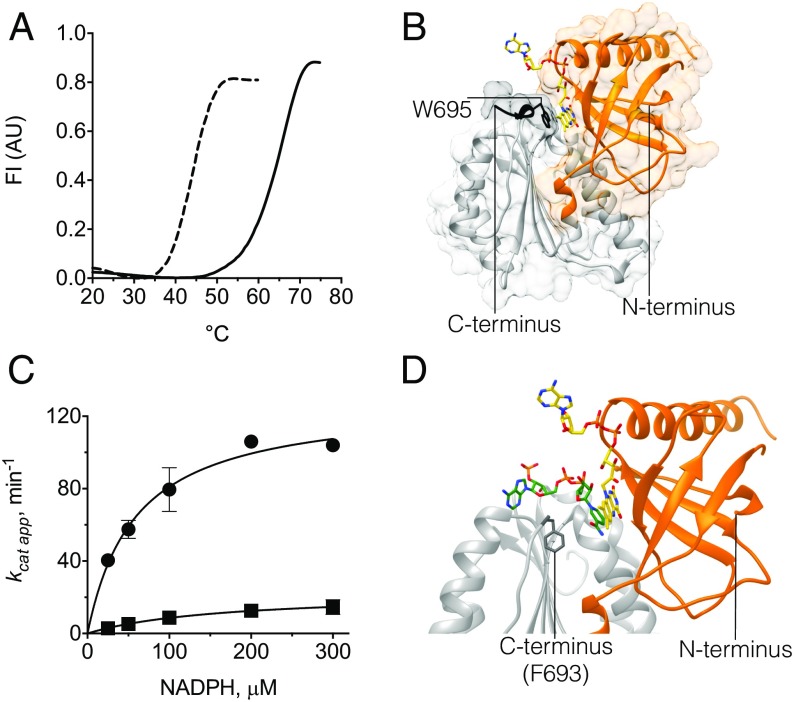

Purified recombinant C. stagnale DH (residues 413–693; csDH) did not retain the FAD cofactor, possibly a symptom of poor protein stability, and crystals did not grow in any of the tested conditions. However, in the course of the protein expression screenings, we serendipitously found that addition of the amino acid sequence PWLELAAA after the C-terminal Phe693 generated a mutant csDH with dramatically enhanced thermal stability (19 °C increase in the unfolding temperature) and FAD retention (Fig. 1A). The C-terminal residues are highly conserved (Fig. S1B), and the described extension may represent a generally effective way to increase the stability of other NOX enzymes. Crystals of mutant csDH were obtained in vapor-diffusion experiments and the structure solved at 2.2-Å resolution (Table S1). The Trp of the added PW695LELAAA positions itself in front of the isoalloxazine ring of FAD with a face-to-face π-stacking interaction (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 C and D). This Trp–FAD interaction hinders access of the nicotinamide ring of NADP+ to its binding pocket. However, we found that the mutated csDH effectively oxidizes NADPH, albeit with a fivefold slower rate compared with the WT (Fig. 1C and Table S2). This observation indicates that the C-terminally added PW695LELAAA residues might locally change conformation to allow NADPH-binding. Indeed, in silico docking shows that upon displacement of Trp695, NADPH can easily be modeled to fit in the crevice at the interface of the NADPH- and FAD-binding lobes of DH with the same binding mode observed across the ferredoxin-NADPH reductase superfamily (Fig. 1D) (16). On this basis, it can be concluded that our csDH mutant is most likely stabilized in an active conformation, which simply requires the displacement of the C-terminally added residues (i.e., Trp695) to allow NADPH binding and flavin reduction.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the mutant csDH domain and its structure in complex with FAD. (A) Thermal denaturation curves demonstrate higher stability of the mutant csDH (solid line, Tm = 67 °C) compared with the WT (dashed line, Tm = 48 °C). Data are representative of three independent experiments. The fluorescence intensity (vertical axis) is plotted against the temperature (horizontal axis). (B) Overall view of csDH with bound FAD (carbons in yellow). The FAD-binding lobe is in orange and the NADPH-binding lobe in gray. Residues of the C-terminal PW695LEL extension are in black. (C) NADPH-oxidase activity of the isolated csDH. WT (●) exhibits kcat = 128.5 ± 9.0 min−1, Km = 58.6 ± 11.0 μM, whereas the C-terminally extended mutant (■) shows kcat = 22.8 ± 3.9 min−1 and Km = 165.3 ± 59.5 μM. In this assay, dioxygen is used as the electron-accepting substrate that regenerates the oxidized flavin. The reaction becomes fourfold faster using ferricyanide as electron acceptor (kcat = 261.9 ± 27.7 min−1 and Km = 84.54 ± 22.8 μM). (D) The NADPH-binding cleft. NADPH (green carbons) is modeled with the nicotinamide stacking against the isoalloxazine moiety of FAD (yellow carbons) by similarity with spinach ferredoxin-reductase (16). Oxygens are in red, nitrogens in blue, and phosphorous in orange. Phe693, at the C terminus, is in dark gray.

Table S1.

Data collection, phasing and refinement statistics for MAD/SAD structures

| Data collection and refinement | csTM (PDB ID code 5O0T) | csTM | csDH (PDB ID code 5O0X) |

| Native | Fe-SAD | ||

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P321 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 52.37 74.57 85.12 | 51.91 73.49 85.07 | 128.28, 128.28, 72.52 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 120 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0 | 1.7383 | 0.8729 |

| Resolution (Å)* | 44.6–2.05 | 85.07–3.15 | 48.04–2.2 |

| (2.11–2.05) | (3.37–3.15) | (2.27–2.2) | |

| Rmerge | 0.065 (0.597) | 0.214 (1.994) | 0.103 (1.237) |

| I/σ(I)* | 10.3 (2.7) | 9.8 (1.1) | 11.4 (1.5) |

| CC1/2* | 0.98 (0.43) | 0.99 (0.38) | 0.99 (0.55) |

| Completeness (%)* | 97.6 (98.2) | 99.0 (94.6) | 99.3 (99.8) |

| Redundancy* | 3.7 (3.8) | 11.6 (10.4) | 5.6 (5.8) |

| Anomalous completeness (%) | — | 98.0 (89.5) | — |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 44.6–2.05 | 48.04–2.2 | |

| No. reflections | 19,905 | 33,160 | |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.187/0.220 | 0.185/ 0.209 | |

| No. atoms | |||

| Protein | 1,650 | 2,066 | |

| Ligands | 205 | 213 | |

| Waters | 63 | ||

| B factors | 99 | ||

| Protein | 36.08 | 44.58 | |

| Ligands | 51.08 | 66.59 | |

| Waters | 53.48 | 51.19 | |

| rmsd | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.017 | 0.013 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.66 | 1.78 | |

| Ramachandran (%) | |||

| Favored | 98 | 99 | |

| Allowed | 2 | 1 | |

| Disallowed | 0 | 0 |

MAD, multiwavelength anomalous dispersion; SAD, single-wavelength anomalous dispersion.

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Table S2.

Kinetic characterization of DH mutants

| csDH construct | kcat (min−1) | Km (μM) |

| WT | 128.5 ± 9.0 | 58.6 ± 11.0 |

| F693PWLELAAA | 22.8 ± 3.9 | 165.3 ± 59.5 |

| N692STOP | 153.3 ± 10.0 | 36.1 ± 7.3 |

| F693S | 303.9 ± 20.1 | 40.4 ± 8.3 |

The rate of NADPH consumption was measured in triplicate as described in SI Materials and Methods.

The structure of the isolated NADP-binding lobe of human NOX2 is available (PDB ID code 3ALF). As expected, its overall conformation is very similar to that of the same region of csDH. It is of note, however, that there is a large outward shift in the position of the C-terminal residues (up to 7.9 Å for Phe570 of NOX2 compared with the homologous Phe693 of csDH) (Fig. S1C). This conformational change might reflect the absence of the FAD-binding domain in the human NOX2 partial structure. Nevertheless, because the superposition of these two structures does not display any structural clash, the shift of the C-terminal Phe also indicates that in NOXs this residue can potentially move inward and outward from the active site.

NOX DH Domain Contains Structural Features That Are Unique in the Ferredoxin-NADP Oxidoreductase Superfamily.

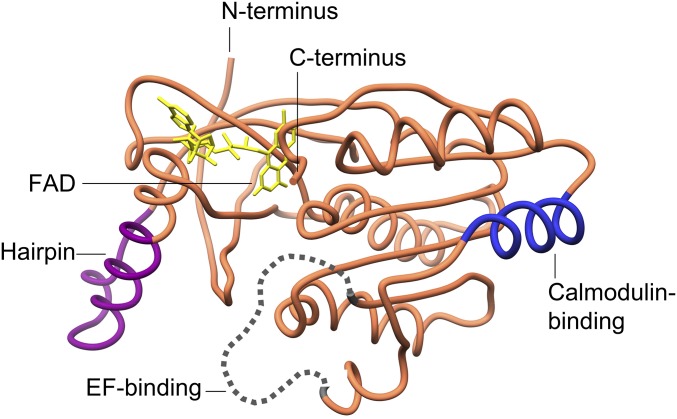

csDH was further compared with ferrodoxin-NADPH reductases to outline key structural features at the heart of enzyme regulation (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1 B and E). A first characteristic element is a hairpin within the FAD-binding lobe (Q489-G509). This segment is longer in human NOX5 than in the other NOX members and binds Hsp90, which is involved in NOX5 stability and activity (17). The other NOX5-specific elements pertain to calcium-regulation, namely two extended segments known to be involved in EF-hand and calmodulin-binding, respectively (18, 19). Upon increase of intracellular Ca2+, the N-terminal EF-hand domain binds to and activates NOX5. In the csDH structure, the EF-hand binding loop is unstructured (D611-T634), probably because of a dynamic role and associated conformational changes that may accompany the enzyme activation. Calmodulin further sensitizes human NOX5 to Ca2+ by binding in a region, which, as now shown by the crystal structure, is a solvent-exposed α-helical segment downstream the EF-binding loop (R644-V663) (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1E). Although calmodulin is not found in prokaryotic cells, the conservation of the calmodulin-binding region (37% identity between human and C. stagnale) (Fig. S1B) may not be merely vestigial, as we cannot exclude the existence of a Ca2+-binding protein with similar function to calmodulin in C. stagnale. In essence, DH can be described in terms of a typical NADP-ferredoxin oxidoreductase scaffold (16), which is enriched by specific regulatory elements and a mobile C-terminal segment.

Fig. 2.

Characteristic structural features of csDH. The domain is depicted in orange with the calmodulin-binding region in blue (R644-V663) (Fig. S1B), the unstructured EF-hand binding loop in dotted gray (D611-T634), and the protruding hairpin of the FAD-binding lobe in purple (Q489-G509).

An Uncommon Oxygen-Reacting Center.

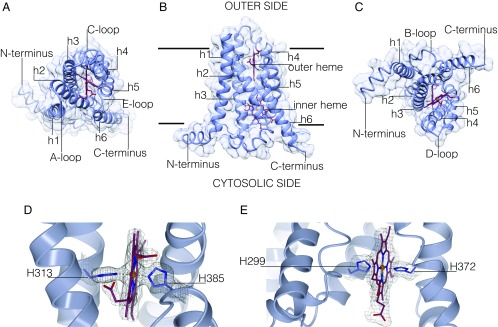

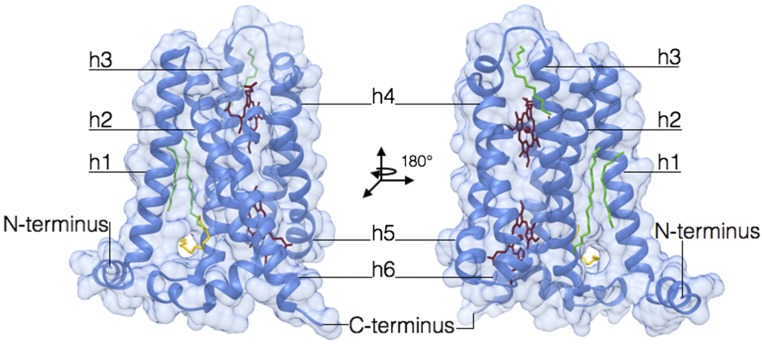

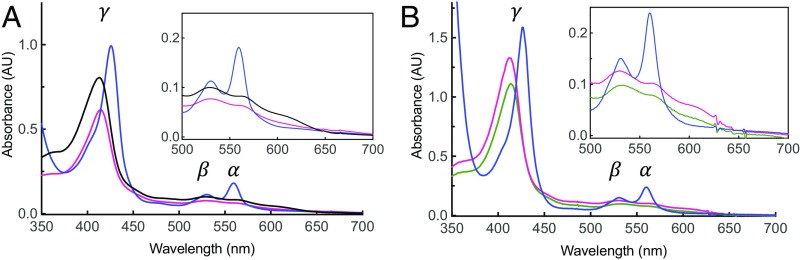

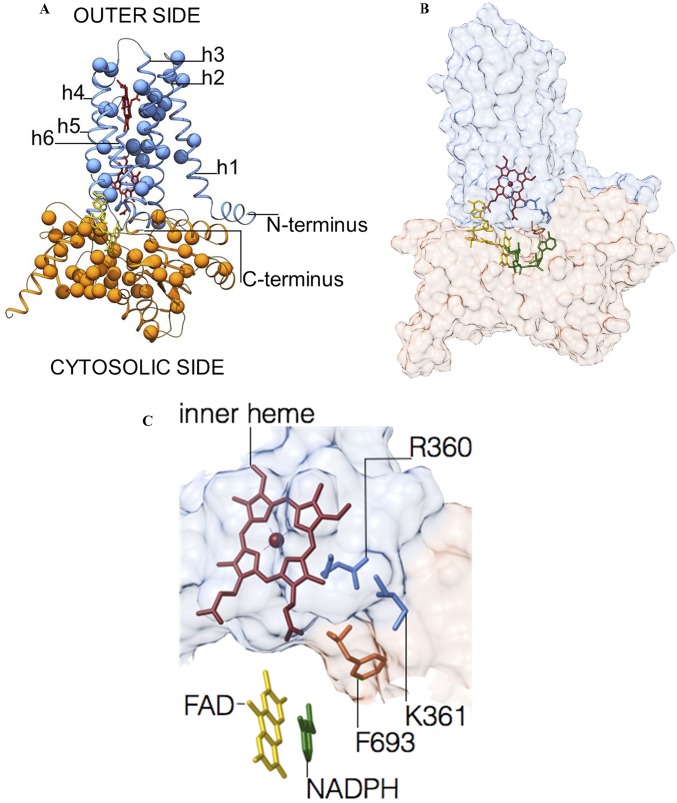

The TM domain of csNOX5 (residues 209–412) was crystallized in a lipid mesophase, which provides a better crystallization environment for membrane proteins (20). Because no suitable homology model was available for molecular replacement, we exploited the anomalous signal of the iron atoms bound to the two b-type heme groups (13). The 2.0-Å resolution crystal structure of csTM has an overall pyramidal shape with a triangular base on the inner membrane side and a narrower apex toward the outer membrane face (Table S1). The domain encompasses six transmembrane helices (h1–h6) and an additional N-terminal α-helix, which runs at the surface of and parallel to the inner side of the membrane (Fig. 3 A–C). The electron density shows the TM to be decorated by four lipid ligands that bind along the helices h1, h3, and h4, and a fifth lipid wedged between the transmembrane helices h1, h2, and h3 (Fig. S2). The two hemes of the transmembrane portion of NOX are positioned with their planes orthogonal to the lipid bilayer in a cavity formed by helices h2, h3, h4, and h5 (Fig. 3C). The line connecting their iron atoms is almost exactly perpendicular to the plane of the bilayer (Fig. 3 A and B). In this way, one heme lies proximal to the cytosolic (inner) side of the domain, whereas the second heme is located toward the outer extracytoplasmic side. The two porphyrins are both hexa-coordinated because they are ligated via two pairs of histidines belonging to helices h3 and h5 (Fig. 3 D and E). Reduction with dithionite leads to a red shift of the Soret γ-band from 414 nm to 427 nm, accompanied by an increase of amplitude of the α- (558 nm) and β- (528 nm) bands, which is characteristic of heme hexa-coordination (Fig. 4A). Consistently, we could not detect any inhibition by cyanide even at high concentrations, as expected for hexa-coordinated hemes (Fig. 4B) (21, 22).

Fig. 3.

TM of NOX consists of six transmembrane helices and contains two heme groups positioned almost orthogonally to the lipid bilayer. (A–C) Overall structure of csTM depicted in different orientations (outer, side, and cytosolic view). Transmembrane helices are labeled sequentially as h1–h6. (D and E) Crystallographic data outline the hexa-coordinated nature of the outer and inner heme groups, respectively. The weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density maps are contoured at 1.4 σ levels.

Fig. S2.

Lipid binding by csTM. Lipid fragments that lie along the lateral surface of the TM are shown in green. The acyl chain lodged inside a tunnel at the bottom of helices 1, 2, and 3 is shown in yellow.

Fig. 4.

UV/visible absorption spectra of native and reduced csTM domain support the hexa-coordinated nature of heme binding to NOX5. (A) Spectra of purified csTM alone (anaerobiosis; black) reduced with dithionite (blue) and reoxidized with dioxygen (purple). (B) csTM does not react with cyanide. Spectra of purified csTM incubated first with 1 mM potassium cyanide (green), then with 10 mM dithionite (blue), and reoxidized with dioxygen (purple). Insets show expanded spectra in the range between 500 and 700 nm.

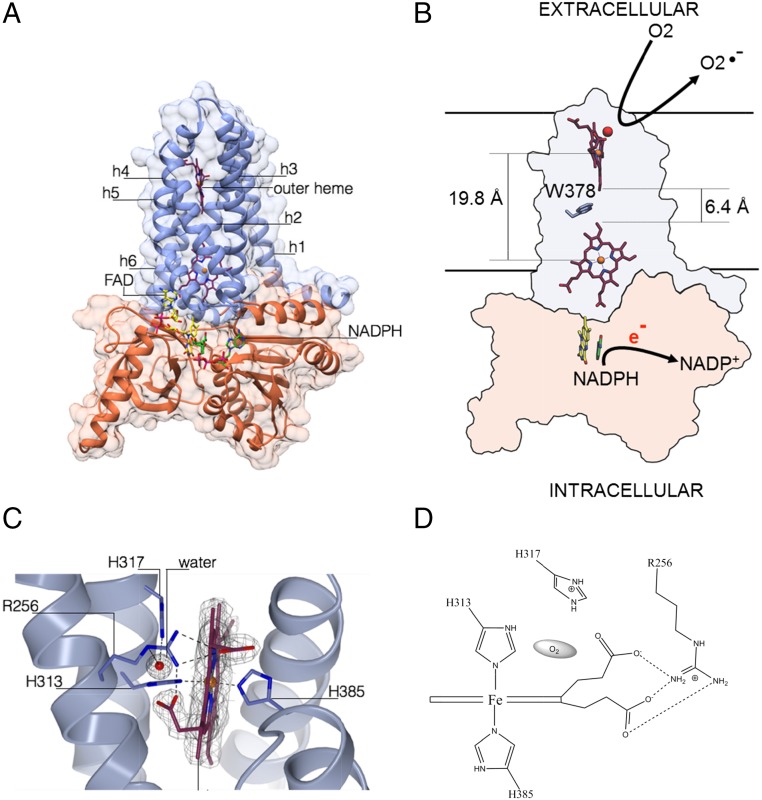

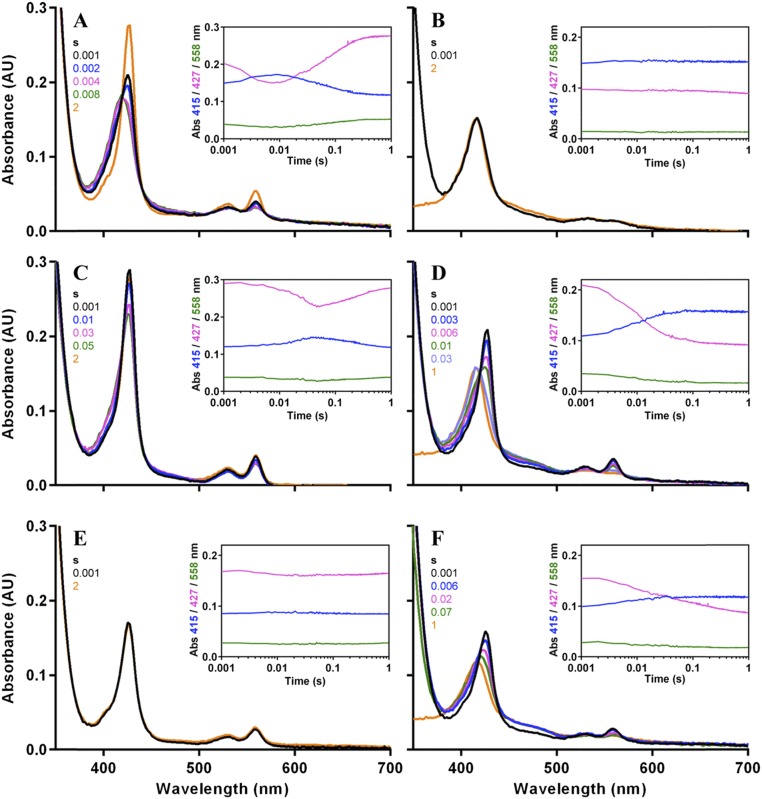

We analyzed the csTM structure to model a plausible route for electron passage across the two hemes. The metal-to-metal distance is 19.8 Å, whereas the shortest interatomic distance (6.4 Å) is between vinyl 2 of the inner heme and vinyl 4 of the outer heme (Fischer nomenclature). A cluster of hydrophobic residues (Met306, Phe348, Trp378) intercalates between the two prosthetic groups; of those, the Trp378 indole is within Van der Waals contact distance from both porphyrins (Fig. 5 A and B). Based on these observations, we hypothesize that a favorite route for electron transfer can be from vinyl 2 of the inner heme via Trp378 to vinyl 4 of the outer heme. The electron is then finally transferred to a dioxygen molecule. In this regard, inspection of the csTM structure reveals an intriguing feature: a small cavity is located above the outer heme and occupied by a highly ordered water molecule (Fig. 5C). This cavity is lined by the propionate 7 of the heme (Fisher nomenclature) and the strictly conserved residues Arg256, His317, and iron-coordinating His313. Many features indicate that the cavity-bound water molecule actually occupies the position of the dioxygen substrate. Its H-bonding environment is clearly suited for O2 binding and sequestration (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the positive charge of Arg256 can electrostatically promote the catalytic production of superoxide, as observed in other oxygen-reacting enzymes (23, 24). In agreement with the notion that the site lined by Arg256 and His317 is involved in O2 binding and catalysis, we found that reoxidation of chemically reduced csTM is greatly impaired by mutations targeting these two residues (Fig. 5 C and D). Rapid kinetics experiments show that reduced WT csTM is very quickly oxidized even at low O2 concentration (∼300 s−1 at 4.5 μM O2). Conversely, the R256S and H317R mutants can be fully reoxidized only at higher O2 concentration (600 μM), with rates at least fivefold lower than observed for WT csTM (Fig. S3 and Table S3). Notably, whereas the R256S mutant displayed the same apparent melting temperature (Tm) as the WT (61 °C), the H317R variant showed lower protein stability (appTm = 43.5 °C) (Table S4). The functional importance of Arg256 and His317 is further documented by disease-inducing mutations affecting the corresponding residues of human NOX2. These mutations were shown to impair catalytic activity (25–27), but until now no mechanistic explanation could be provided (for an extended analysis of NOX2 mutations, see Fig. S4A and Table S5).

Fig. 5.

A model for the TM–DH core of NOX catalytic subunit as gathered from the crystal structures of DH and TM domains from csNOX5. (A) The in silico docking of csTM (light blue) and csDH (orange) structures is shown in a putative active conformation (Fig. S4 and SI Materials and Methods for details). (B) A distance of 19.8 Å separates the metal centers of the two heme groups of TM. Electron transfer may follow a path through Trp378. This residue corresponds to a Val362 in human NOX5 (but the adjacent Trp363 may also offer a suitable route), Phe215 in human NOX2, and Phe200 in human NOX4 (Fig. S1B and Table S5). (C) A highly ordered water molecule is present in a cavity lined by the outer heme at 3.8 Å distance from the iron (Fig. 3 A–C) and exposed toward the external milieu, highlighting the oxygen-reacting center. The weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density map is contoured at 1.4 σ level. (D) Schematic view of the cavity with groups putatively interacting with dioxygen.

Fig. S3.

Reaction with dioxygen of csTM domain. Spectral changes were recorded with a stopped-flow instrument after mixing anaerobically reduced csTM (1.3–2.4 μM enzyme/0.5 mM dithionite) with dioxygen. Insets show the corresponding stopped-flow traces at the characteristic absorbance maxima for oxidized or reduced enzyme (see Fig. 4). (A) The first spectrum after mixing the reduced WT csTM with an equal volume of buffer containing a low dioxygen concentration (4.5 μM after stopped-flow mixing) suggested the presence of partially reoxidized enzyme. A high reoxidation rate for WT csTM was estimated by fitting the stopped-flow trace at 427 nm to a single-exponential function (∼300 s−1). The rate of reduction of the reoxidized WT csTM was significantly slower (10 s−1). The spectrum of the completely reduced enzyme was observed after 2 s (orange). (B) When a higher dioxygen concentration was used (600 μM after stopped-flow mixing), WT csTM was completely reoxidized within the dead time of the stopped-flow instrument (1 ms). (C–F) In the case of R256S and H317R mutants, the outcome of similar experiments was different from that of the WT enzyme. In the presence of lower dioxygen concentration (4.5 μM), minimal or no amounts of reoxidized protein were observed even after 2 s (C for R256S and E for H317R). Only, by using higher dioxygen concentration (600 μM), significant reoxidation of both mutants was observed (D and F). For these reactions, stopped-flow traces at 427 nm were best fit to a double exponential function with an initial faster phase accounting for 87% (R256S) and 59% (H317R) of the total absorbance change, respectively. The observed rates were 44 and 3 s−1 for H317R and 80 and 7 s−1 for R256S. It might be possible that the two distinct phases reflect the different reoxidation rates of the inner and outer hemes bound to TM mutants.

Table S3.

Rapid kinetic parameters for csTM

| csTM | Parameter | Value |

| Reoxidation | ||

| WT | k | 294 ± 14 |

| a | 0.10 ± 0.01 | |

| R256S | k1 | 80 ± 12 |

| k2 | 7 ± 1 | |

| a1 | 0.1097 ± 0.0002 | |

| a2 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | |

| H317R | k1 | 44 ± 1 |

| k2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | |

| a1 | 0.040 ± 0.001 | |

| a2 | 0.02741 ± 0.00003 | |

| Rereduction | ||

| WT | k | 10.4 ± 0.2 |

| a | 0.128 ± 0.002 | |

Conditions: 50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol (vol/vol), at pH 7.4 and 25 °C; 4.5 and 600 μM O2 for WT and mutants, respectively. Stopped-flow traces at 427 nm were fit to a proper exponential function, where k is the observed rate constant for either enzyme reoxidation or the reduction of reoxidized enzyme and a is the amplitude of the absorbance change for the observed phases. For double-exponential processes, the fast and slow observed phases are denoted 1 and 2, respectively. SDs of two replicates are shown.

Table S4.

Melting temperatures for different variants of csTM

| csTM variant | Tm (°C) |

| WT | 61.5 |

| R256H | 61.6 |

| H317R | 43.5 |

Fig. S4.

Predicted interactions between DH and TM. (A) Overall view of the TM–DH complex. The spheres outline the Cα positions of the residues which are mutated in NOX2-deficient patients affected by chronic granulomatous disease (DH domain in orange, TM domain in blue; FAD in yellow; heme prostethic groups in red; only missense mutations are shown). The mutated residues are scattered throughout the protein. As detailed in Table S5, most disease-causing mutations affect amino acids that are part of the domain hydrophobic cores; the NADPH-, FAD-, heme-, and oxygen-binding sites; and regions involved in interdomain interactions or electron transfer. (B) Overall and (C) closed-up views of the interacting surfaces between DH (light orange) and TM (light blue) of csNOX5 (Fig. 5A) outline Arg360, a 100% conserved residue in the D loop (Fig. S1A) near propionate 6 of the inner-side heme. In close proximity to the toggle switch Phe693, there is the positively charged Lys361, which is an Arg in the other NOXs, except for the constitutively active NOX4 where there is a Val (Fig. S1B). The flavin and nicotinamide rings of FAD and NADPH are in yellow and green, respectively. The pictures were generated from the model built by rigid-body docking of the crystal structures of the DH and TM domains as shown in Fig. 4 and described in SI Materials and Methods.

Table S5.

Structural analysis of NOX2 missense mutations causing chronic granulomatous disease

| Domain and residues | Role |

| Transmembrane domain | |

| Trp18Cys (Tyr228) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Gly20Arg (Phe230) | Hydrophobic surface embedded in the membrane |

| Tyr41Asp (Tyr243) | Outer heme, oxygen-binding site |

| Thr42Arg (Glu244) | Poorly conserved region |

| Leu45Arg (Gly247) | Poorly conserved region |

| Ala53Asp (Ala255) | Oxygen-binding site |

| Arg54Gly, Arg54Ser, Arg64Met (Arg256) | Oxygen-binding site |

| Ala55Asp (Gly257) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Pro56Leu (Cys258) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Ala57Glu (Gly259) | Oxygen-binding site, outer heme binding |

| Cys59Phe, Cys59Arg, Cys59Tyr, Cys59Trp (Thr261) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Asn63Lys (Asn265) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Cys64Arg (Gly266) | In contact with Trp378 |

| Met65Arg (Ala267) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Leu66Pro (Leu268) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| His101Tyr (Hys299) | Coordinating the iron of the inner cytosolic heme |

| Met107Arg (Val305) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Ser112Pro (Ala310) | Interacting with the outer heme |

| His115Tyr, His115Gln (His313) | Coordinating the iron of the outer heme; oxygen-binding site |

| His119Arg (His317) | Oxygen-binding site |

| Leu120Pro (Phe318) | Oxygen-binding site |

| Trp125Cys (Thr323) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Arg130Leu, Arg130Pro | Poorly conserved region |

| Leu141Pro (Gln330) | Beginning of transmembrane helix |

| Ser142Pro (Ser331) | Packing of transmembrane helices |

| Leu153Arg | Poorly conserved region; deleted in NOX5 |

| Ala156Thr | Poorly conserved region; deleted in NOX5 |

| Lys161Arg, Lys161Asn | Poorly conserved region; deleted in NOX5 |

| Gly179Glu, Gly179Arg (Gly341) | Outer heme binding |

| Cys185Arg (Val347) | In contact with Trp378 |

| Ser193Pro, Ser193Phe (Ala-354) | Helical packing |

| Phe205Ile (Phe368) | Inner heme binding |

| His209Tyr, His209Gln, His209Arg (His372) | Coordinating the iron of the inner heme |

| Leu211Arg, Leu211Pro (Gly374) | In contact with Trp378 |

| His222Tyr, His222Arg, His222Leu, His222Asn (His385) | Coordinating the iron of the outer heme |

| Ala224Gly | NOX2-specific insertion |

| Glu225Val | NOX2-specific insertion |

| Cys244Ser | NOX2-specific insertion |

| Cys257Arg | NOX2-specific insertion |

| Pro260Arg | NOX2-specific insertion |

| Dehydrogenase domain | |

| Lys299Asn (Asn-419) | DH surface |

| Thr302Pro (Leu422) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| His303Asn/Pro304Arg (Leu423/Pro424) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Glu309Lys (Gly429) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Leu310Pro (Leu430) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Met312Lys, Met312Arg (Val432) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Gly322Glu (Gly443) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Ile325Phe (Leu446) | Predicted site for interaction with TM |

| Cys329Arg (Cys450) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Ser333Pro (Ser454) | Predicted site for interaction with TM |

| His338Gln, His338Tyr, His338Asn, His338Arg (His459) | FAD-binding site |

| Pro339Leu (Pro460) | FAD-binding site |

| Thr341Ile, Thr341Lys (Thr462) | FAD-binding site |

| Leu342Gln (Ile463) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Thr343Pro (Ser464) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Ser344Pro, Ser344Phe (Ser465) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| His354Pro, His354Arg (His476) | FAD binding site |

| Arg356Pro (Arg478) | NADP-binding site |

| Gly359Val, Gly359Ala, Gly359Arg (Gly481) | NADP-binding site |

| Trp361Arg (Trp483) | NADP-binding site |

| Thr362Arg (Thr484) | NADP-binding site |

| Leu365Pro (Leu487) | NADP-binding site |

| Cys369Arg (Ile491) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Ile385Arg (Val512) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Gly389Val, Gly389Glu, Gly389Ala, Gly389Arg (Gly516) | Predicted site for interaction with TM |

| Pro390Leu (Pro517) | Predicted site for interaction with TM |

| Met405Arg (Ile532) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Gly408Glu, Gly408Arg (Cys535) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Gly412Glu, Gly412Arg (Gly539) | NADP-binding site |

| Pro415Arg, Pro415Leu, Pro415His (Pro542) | NADP-binding site |

| Ser418Tyr (Ser545) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Leu420Pro (Leu547) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Ser422Pro (Ser549) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Cys445Arg (Asn572) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Trp453Arg (Trp580) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Leu474Arg (Phe597) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Thr481Pro (Thr604) | Core residue engaged in many interactions |

| Ala488Asp (Asp611) | Putative regulatory; EF-binding region in NOX5 |

| His495Pro (Gln626) | Putative regulatory; EF-binding region in NOX5 |

| Asp500Tyr, Asp500Phe, Asp500His, Asp500Asn, Asp500Gly (Asp631) | Putative regulatory; EF-binding region in NOX5 |

| Leu505Arg, Leu505Pro (Leu636) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Gly512Arg (Gly643) | Strictly conserved Gly residue |

| Trp516Arg, Trp516Cys (Trp647) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Ala524Val (Ala655) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Val534Asp (Val665) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Cys537Arg (Cys668) | NADP-binding site |

| Leu542Ser (Leu673) | NADP-binding site |

| Leu546Arg (Leu677) | Hydrophobic core residue |

| Glu568Lys (Glu691) | NADP-binding site |

Mutations are from the variation registry for X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, structure.bmc.lu.se/idbase/CYBBbase/browser.php?content=browser (46). The corresponding csNOX5 residues are in parenthesis.

These findings have far-reaching implications for our understanding of the chemical mechanism of ROS generation. Dioxygen binding does not appear to occur through direct coordination to the iron of the heme, which is in a hexa-coordinated state (Fig. 5C). Rather, dioxygen interacts noncovalently with the prosthetic group and surrounding hydrophilic side chains. This observation implies that superoxide formation does not happen through an innersphere mechanism, which is brought about by the oxygen directly coordinating to the iron as, for example, in the globin class of hemoproteins (28). It is instead an outersphere reaction that affords reduction of molecular oxygen through an electron transfer step, as originally suggested by Isogai et al. (29). This may occur either by direct contact between the reduced heme and O2 or be mediated by the iron-coordinating His313 side chain.

A Structural Framework for NOX Catalysis and Regulation.

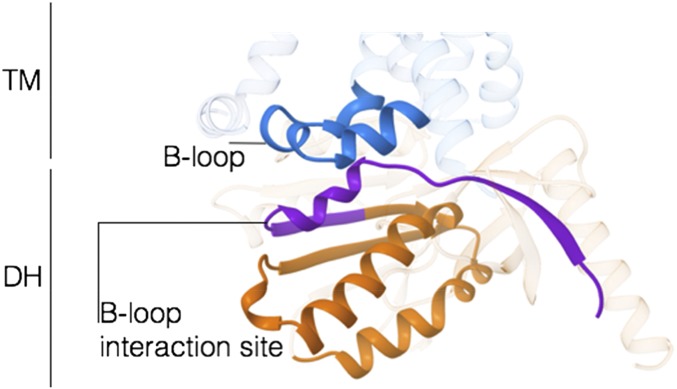

With the insight gained from the individual DH and TM domains, we next addressed the issue of their assembly to model the NOX catalytic core. A first noteworthy observation is that the surface on the inner side of TM is remarkably complementary in shape to the bilobal surface of DH, where the flavin ring is exposed (Fig. 5 A and B and Fig. S4 B and C). Furthermore, the C terminus of the csTM structure (residue 412) must necessarily be close in space to the N terminus of csDH (residue 413). On these bases, the two domain structures were computationally docked to generate a full TM–DH complex (SI Materials and Methods for details). This model corresponds to the epsilon splicing isoform of human NOX5, which lacks the regulatory N-terminal EF-hand domain (30). Of relevance, the catalytic subunits of the oligomeric NOX1–4 also consist only of DH–TM with no other domains (14). Therefore, the general functional and catalytic implications of our analysis are likely to be relevant to the whole NOX family.

A first point outlined by the TM–DH model is that the flavin is positioned with its exposed dimethylbenzene ring in direct contact with the TM’s inner heme (the propionate chains in particular) (Fig. 5B). This geometry is obviously suited to promote the interdomain electron transfer that injects the NADPH-donated electrons from the flavin to the heme-Trp378-heme array. Another critical observation concerns the extensive interdomain interactions involving the C-terminal residues of DH and the loops connecting helices h2–h3 and h4–h5 of TM (known as B and D loops, respectively) (Fig. 3C and Fig. S1B). In NOX4 and NOX2, these loops were shown to contribute to the regulation of the enzyme activity (31, 32). Of note, our structural model positions the TM’s B-loop in direct interaction with a highly conserved α-helix/β-strand element of DH (Fig. S5). These residues (L507-L533) are part of the B-loop interacting region as reported for NOX2 and -4 based on peptide-binding experiments (Fig. S1B) (31). Moreover, Arg360 and Lys361 on loop D are modeled in direct contact with the C-terminal Phe693 of DH, in the core of the nicotinamide-binding site (Fig. S4 B and C). This arrangement is fully consistent with published data demonstrating that both loops contribute to the ROS-producing activity and its regulation in NOX2/4 (31, 32).

Fig. S5.

Interdomain regulatory interactions in NOX. Residues L507-L533 (purple) mediate the interaction between the B-loop of TM (H276-E297, blue) and the DH domain (I534-T593, orange). See ref. 31.

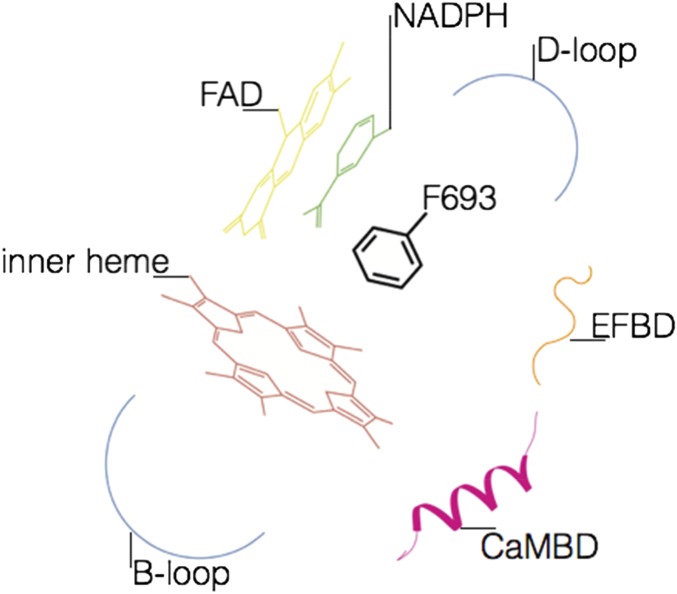

The elucidation of NOX 3D structure outlines a general scheme for NOX regulation with the C-terminal residues functioning as regulatory toggle switch. A mobile C-terminal segment is hinted by the above-discussed structural comparisons between the NADPH-binding lobes of csDH and human NOX2 (Fig. S1C). Notably, an aromatic C-terminal residue (i.e., Phe693 in csNOX5) is widespread among NADP-ferredoxin reductases, where it is often found to change its conformation depending on NADPH-binding (16). The substitution Phe693Ser showed a twofold increase in Vmax compared with the WT, whereas the deletion of Phe693 did not elicit any remarkable change on the steady-state kinetic properties of the DH domain (Table S2). This observation implies that Phe693 has a limited influence on the catalysis of the isolated DH domain, which is in a deregulated active state. Rather, the regulatory role of strictly conserved Phe693 is predicted to emerge only in the context of the full-length protein. Phe693 and nearby C-terminal residues may function as a receiver that conformationally transduces inhibitory or activating signals from other regulatory domains or subunits. For example, in the case of NOX5, the regulatory calmodulin- and EF-hand binding segments are located in proximity of the C-terminal residues and NADPH-binding site (Fig. 2). It can be envisioned that Ca2+-dependent activation may entail the binding of EF-hand and calmodulin to their respective receiving loops, thereby promoting the NADPH-binding conformation of the nearby residues (Fig. S6). It can also be hypothesized that these conformational changes further promote the attainment of the competent redox-transfer conformation at the flavin–heme interface where the D-loop is located (Fig. S6). Given the high conservation of the C-terminal residues, similar mechanisms to convey regulatory signals to the catalytic core might be operational also in other NOXs (33, 34) (Fig. S1B). Of interest, an allosteric mechanism of enzyme regulation involving NADH-binding has been recently found also in the flavoenzyme apoptosis-inducing factor (35). The crucial feature of this mechanistic proposal is that NADPH-oxidation at the flavin site takes place only when the enzyme is in the active conformation, thus preventing the risk of NADPH-derived electrons being diverted to nonproductive redox reactions.

Fig. S6.

Schematic representation of the toggle switch and surrounding structural elements. The toggle switch of NOX is composed by an aromatic residue at the C terminus crowned by the cofactors NADPH, FAD, and inner heme, as well as regulatory elements from the DH and TM domains (the EF-hand domain binding site in orange, the calmodulin-binding region in pink, and the two intracellular B and D loops of the TM in blue).

The powerful production (or its deregulation/deficiency) of ROS by NOXs underlies pathological conditions, such as oxidative stress, malignancies, neurodegenerative disease, senescence, and chronic granulomatous disease (1–12) (Fig. S4A and Table S5). Our results highlight key structural elements common to the entire NOX family, such as the toggle-switch at the C terminus and the dioxygen binding pocket. The NOX structural model presented here and its analysis bear strong implications for the design of drugs targeting the NOX family.

SI Materials and Methods

Cloning, Protein Expression, and Purification.

The gene encoding for Cylindrospermum stagnale NOX5 was purchased from GeneScript. The NADPH-dehydrogenase domain of csNOX5 (residues 413–693; csDH), either WT or mutant, carrying an N-terminal Strep-tag followed by a tobacco etch virus cleavage site, was expressed in the Escherichia coli strain BL21-RP plus cells (Novagen) grown in Terrific Broth. Once the cells reached OD600 = 1.2, protein expression was induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 17 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min and the pellet was resuspended on ice in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 300 mM NaCl]. Proteases inhibitors (1 μM leupeptine, 1 μM pepstatine, and 1 mM PMSF) were added before cell disruption by Emulsiflex C3 (Avestin) and centrifuged at 60,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was purified using a Strep column with an ÄKTA system (GE Healthcare) and the csNOX5 protein was eluted with 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 3 mM desthiobiotin. The sample was concentrated using an Amicon concentrator with a 10-kDa cut-off and loaded on a desalting column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in low salt buffer [LSbuffer; 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 50 mM NaCl]. The desalted protein was injected into a MonoQ column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in the same buffer. The sample was collected, concentrated and, after addition of 200 μM FAD (final concentration), was loaded on a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in LSbuffer. Peak fractions were pooled and concentrated to 7–10 mg/mL using the following extinction coefficients: ε280 = 48.150 M−1 cm−1 for csDH and ε280 = 48.650 M−1 cm−1 for csDH-PWLELAAA. A UV-visible scan of the purified csDH-PWLELAAA showed also a peak at 461 nm (ε461 = 8,100 M−1 cm−1), thus indicating FAD incorporation.

The TM part of csNOX5 (residues 209–412; csTM) was inserted into a modified pET24b carrying an N-terminal FLAG-(His)8-SUMO tag. The plasmid was used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) RP Plus (Novagen). The transformed cells were grown in 2xTY media at 37 °C with appropriate antibiotics until OD600 reached 1.2. Overexpression of csTM was induced by the addition of 0.4 mM IPTG and the temperature was shifted to 17 °C for 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol], and supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 μM leupeptine, 1 μM pepstatine, and 1 mM PMSF). All subsequent steps were carried out at 4 °C. After sonication, the lysed cells were centrifuged at 3,000 × g to get rid of cell debris and the membranes were isolated by centrifugation at 72,000 × g for 2 h. The pellet was washed with high-salt buffer [50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol], centrifuged as before, and resuspended in solubilization buffer [50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1% (wt/vol) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM)]. Solubilization proceeded for 2 h. The solubilized sample was centrifuged and the supernatant was loaded onto a TALON resin. The resin was washed with lysis buffer containing 0.05% (wt/vol) DDM and eluted with elution buffer [50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.05% DDM, 150 mM imidazole]. The eluted protein was treated with SUMO protease overnight and passed again onto TALON resin to eliminate the purification tag. Free hemin (in 100% DMSO from Sigma) was mixed with csTM and the sample applied to a Superdex-200 (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in storage buffer [50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.03% (wt/vol) DDM]. The peak was concentrated to 25 mg/mL using an Amicon ultra 50 kDa. The protein absorbance spectrum was fully consistent with csTM containing two bound heme groups.

The mutations of TM and DH were obtained by the In-fusion (Clontech) method following the manufacturer’s instructions. The corresponding mutant proteins were purified following the same protocol a WT csTM. The TM domain mutants bound two heme groups as indicated by their absorbance spectra which were identical to that of the WT csTM.

Thermal Stability Assay of csDH.

The Tm of csDH was measured by thermal shift experiments. SYPRO orange dye (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions in LSbuffer. As csDH693-PWLELAAA tightly binds FAD, the flavin fluorescence was also monitored to provide an additional measurement of the Tm. In all cases, the assay was performed in 20-μL final volume using 15 μM protein in LSbuffer. The fluorescence was monitored over a temperature gradient from 20 to 90 °C reading every 0.5 °C [Instrument settings: FAD, excitation (Ex.) 470–500 nm/emission (Em.) 520–540 nm; SPYRO orange, Ex. 470–500 nm/ Em. 540–700 nm].

Thermal Stability Assay of csTM.

The apparent Tm of the csTM WT and mutants was assessed by monitoring heme loss (absorbance at 414 nm) upon incubation of the TM at various temperatures. Briefly, 5 μg of purified protein were incubated at the specified temperature for 30 min. The protein was then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove aggregates. The supernatant was applied to a Superdex-200 (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in storage buffer [50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.03% (wt/vol) DDM] on HPLC (Shimadzu) maintained at 16 °C. The melting curve was built by measuring the height of the elution peak at 414 nm for each temperature and data were analyzed by nonlinear regression using Prism software (GraphPad).

Activity Assay on Purified csDH Domain.

The activity of the purified csDH domain was measured under aerobic condition following the oxidation of NADPH at 340 nm (ε = 6.22 M−1 cm−1) in a Cary 100 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Varian) equipped with a thermostated cell holder (T = 25 °C). The reaction was carried out with 2 μM protein and different concentrations of NADPH in a final volume of 110 μL of 50 mM Hepes pH 7.5. 300 μM of FAD were added to WT DH and Phe693 mutants. Initial apparent velocities were plotted against NADPH concentration using Michaelis–Menten equation to calculate Km and Kcat (GraphPad Prism software).

Visible Spectra.

All of the spectra were recorded with Agilent Diode Array at 25 °C. For anaerobiosis experiments, a sealed cuvette was used under Argon flow. Next, 1 mM sodium dithionite was mixed with 6 μM csTM in storage buffer with or without 5 mM sodium cyanide and let react. After 1 h the cuvette was open to air or pure oxygen was fluxed into it.

Rapid Kinetics.

The reoxidation of the csTM domain was investigated using a SX20 stopped-flow spectrometer (Applied Photophysics) in single-mixing mode. A xenon lamp and a photodiode array detector were used. All experiments were carried out in 50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol (vol/vol), at pH 7.4 and 25 °C. All assays were run in duplicate by mixing equal volumes of reactants. To make the stopped-flow spectrometer anaerobic, the flow-circuit of this apparatus was repeatedly washed with anaerobic buffer. Anaerobic solutions contained a dioxygen-scavenging system consisting of Aspergillus niger glucose oxidase (2 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) and glucose (10 mM). Solutions (2–3 mL) were prepared in glass vials (5 mL) sealed with a screw-cap with hole and PTFE/silicone septum. Next, 100% nitrogen or dioxygen was bubbled through the solutions for at least 10 min to make them anaerobic or to reach a dioxygen concentration of 1.2 mM at 25 °C, respectively. To obtain a solution containing 9 μM dioxygen, the proper volumes of anaerobic and air-saturated buffers were mixed. Only in the case of the enzyme solution, 100% nitrogen was blown on the surface of the solution for 30 min in ice. The anaerobic reaction of csTM enzymes with sodium dithionite in a sealed vial yielded completely reduced enzyme only when the sodium dithionite/enzyme ratio was higher than stoichiometric. Specifically, reduced enzymes were prepared by injecting 200 mM sodium dithionite (5 μL/mL enzyme) into the anaerobic vial using a gas-tight Hamilton syringe. Concentrations after stopped-flow mixing were 1.3–2.4 μM for enzyme, 0.5 mM for sodium dithionite, and 4.5 μM or 600 μM for dioxygen. When a decrease in absorbance at 427 nm because of the enzyme reoxidation was observed, the corresponding stopped-flow trace was fit to an appropriate exponential function to determine the observed rates using the software Pro-Data (Applied Photophysics).

Construction of the Full-Length NOX Model.

A first visual analysis immediately indicated that the 3D structures of the two domains could be easily docked with the outer heme and the flavin within 5 Å distance from each other and C-terminal Lys412 of TM linked to N-terminal Glu413 of DH. Moreover, this first manually built model positioned the B and D loops of TM in direct contact with the loops surrounding the flavin- and NADP-binding sites of DH. Notably, DH residues 515–530 were predicted to interact with loop B (280–292) of TM. This observation was fully consistent with published peptide-binding experiments on human NOX2 and NOX4, which identified the residues homologous to 507–533 of csNOX as the B-loop binding region (31) (Fig. S1B). The docking of the two domains was further refined with Haddock, a top-performing protein-docking program according to the recent CASP-CAPRI experiment (44, 45). Haddock allows the implementation of user-defined restrains. Specifically, Asn288 (B-loop of TM), Lys361 (D-loop of TM), Thr520 (B-loop binding region of DH) (31), and Phe693 (flavin-interacting C terminus of DH) were defined as “active” residues: that is, directly involved in the domain–domain interactions. Remarkably, the top-scoring model generated by Haddock (buried surface of 1980 Å2; Haddock score of −2.3; the lowest the better) showed Lys412 (C terminus of TM) to be within 4.5 Å distance Glu413 (N terminus of DH), a finding that added confidence to the validity of the docking calculation. The model was slightly adjusted (<2.5 Å shift) to position Lys412 and Glu413 in an even closer (linked) position. In this way, the flavin dimethybenzene ring and a heme propionate resulted to be in van der Waals contact, consistent with electron transfer directly occurring across the two prosthetic groups. The geometry of the model was further validated by Qmean server for model quality estimation.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression, purification, mutant preparation, and enzymatic assays are described in SI Materials and Methods. Initial crystallization experiments on the csDH and csDH-PWLELAAA were carried out at 20 °C using Oryx8 robot (Douglas Instruments) and sitting-drop vapor-diffusion technique. The drops were composed of 0.2 μL of 7 mg/mL protein in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 0.2 μL of reservoir from commercial screens (JCGS core suite I, II, III, and IV from Qiagen). Crystals of csDH-PWLELAAA grew overnight in two different conditions: (i) 160 mM Ca-acetate, 80 mM Na-Cacodylate pH 6.5, 14% (wt/vol) PEG 8000, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol; and (ii) 100 mM CHES pH 9.5, 40% (vol/vol) PEG 600. Crystals used for data collection were obtained using a reservoir consisting of 160 mM Ca-acetate, 80 mM Na-Cacodylate pH 6.5, 12–16% (wt/vol) PEG 8000, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. csTM was concentrated to 25 mg/mL and mixed with monoolein (1-oleoyl-rac-glycerol) in a 2:3 protein to lipid ratio (wt/wt) using two coupled syringes (Hamilton) at 20 °C. The in meso mix was dispensed manually using a Hamilton syringe coupled to a repetitive dispenser onto a sandwich plate in a 120-nL bolus overlaid by 1 μL of precipitant solution. Red csTM crystals grew in 2 d at 20 °C in 30% (vol/vol) PEG300, 100 mM Li2SO4, 100 mM Mes-KOH pH 6.5.

csDH crystals were harvested and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data were measured at 100 K at beam-lines in the Swiss Light Source (Villigen, Switzerland) and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France). Data were indexed and integrated with XDS (36) and scaled with aimless (CCP4suite) (37). The structure of csDH was solved by molecular replacement using Balbes (37). Initial amino acid placement was carried out using phenix.autobuild (38) and checked by Coot. Refinement at 2.0 Å was done by iterative cycles of Refmac5 (37) and Coot (39). Datasets for the csTM were collected at European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France), Swiss Light Source (Villigen, Switzerland), and Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (Hamburg, Germany). They were processed with XDS (36) and scaled with aimless (37). The initial phases were obtained by iron-based single-wavelength anomalous dispersion using the program autoSHARP (40). Two iron sites were identified and a crude helical model was built by phenix.autobuild. Phases were recalculated on the native dataset using DMMULTI (41). The model was further improved with iterative cycles of coot, phenix.fem and Refmac5 (38, 39). Images were prepared using Chimera (42) and CCP4MG (37). Electron flow trajectory was calculated with VMD Pathways1.1 plug-in (43).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Swiss Light Source, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, and Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron for providing synchrotron radiation facilities, and their staff for supervising data collection; Stefano Rovida and Federico Forneris for providing technical support with inhibition assays and crystallographic analyses; Thomas Schneider (European Molecular Biology Laboratory–Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron, Hamburg) for his help and assistance; and Claudia Binda and Federico Forneris for critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the authors’ laboratory is supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (IG-15208) and the Italian Ministry for University and Research (PRIN2015-20152TE5PK_004). X-ray diffraction experiments were supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under BioStruct-X (Grants 7551 and 10205).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [transmembrane domain (PDB ID code 5O0T) and dehydrogenase domain (PDB ID code 5O0X)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1702293114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: Physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambeth JD, Neish AS. Nox enzymes and new thinking on reactive oxygen: A double-edged sword revisited. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill S, Brault J, Stasia MJ, Knaus UG. Genetic disorders coupled to ROS deficiency. Redox Biol. 2015;6:135–156. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirokmány G, Donkó Á, Geiszt M. Nox/Duox family of NADPH oxidases: Lessons from knockout mouse models. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drummond GR, Selemidis S, Griendling KK, Sobey CG. Combating oxidative stress in vascular disease: NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:453–471. doi: 10.1038/nrd3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuroda J, et al. NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) is a major source of oxidative stress in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15565–15570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002178107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao HM, Zhou H, Hong JS. NADPH oxidases: Novel therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoste C, Rigutto S, Van Vliet G, Miot F, De Deken X. Compound heterozygosity for a novel hemizygous missense mutation and a partial deletion affecting the catalytic core of the H2O2-generating enzyme DUOX2 associated with transient congenital hypothyroidism. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:E1304–E1319. doi: 10.1002/humu.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Block K, Gorin Y. Aiding and abetting roles of NOX oxidases in cellular transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:627–637. doi: 10.1038/nrc3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weyemi U, et al. ROS-generating NADPH oxidase NOX4 is a critical mediator in oncogenic H-Ras-induced DNA damage and subsequent senescence. Oncogene. 2012;31:1117–1129. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogrunc M, et al. Oncogene-induced reactive oxygen species fuel hyperproliferation and DNA damage response activation. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:998–1012. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teixeira G, et al. Therapeutic potential of NADPH oxidase 1/4 inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. June 7, 2016 doi: 10.1111/bph.13532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finegold AA, Shatwell KP, Segal AW, Klausner RD, Dancis A. Intramembrane bis-heme motif for transmembrane electron transport conserved in a yeast iron reductase and the human NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31021–31024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Krause KH, Xenarios I, Soldati T, Boeckmann B. Evolution of the ferric reductase domain (FRD) superfamily: Modularity, functional diversification, and signature motifs. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng G, Cao Z, Xu X, van Meir EG, Lambeth JD. Homologs of gp91phox: Cloning and tissue expression of Nox3, Nox4, and Nox5. Gene. 2001;269:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng Z, et al. A productive NADP+ binding mode of ferredoxin-NADP + reductase revealed by protein engineering and crystallographic studies. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:847–853. doi: 10.1038/12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen F, et al. Nox5 stability and superoxide production is regulated by C-terminal binding of Hsp90 and CO-chaperones. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;89:793–805. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tirone F, Radu L, Craescu CT, Cox JA. Identification of the binding site for the regulatory calcium-binding domain in the catalytic domain of NOX5. Biochemistry. 2010;49:761–771. doi: 10.1021/bi901846y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tirone F, Cox JA. NADPH oxidase 5 (NOX5) interacts with and is regulated by calmodulin. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1202–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caffrey M. A comprehensive review of the lipid cubic phase or in meso method for crystallizing membrane and soluble proteins and complexes. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2015;71:3–18. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X14026843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iizuka T, Kanegasaki S, Makino R, Tanaka T, Ishimura Y. Studies on neutrophil b-type cytochrome in situ by low temperature absorption spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:12049–12053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miki T, Fujii H, Kakinuma K. EPR signals of cytochrome b558 purified from porcine neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19673–19675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattevi A. To be or not to be an oxidase: Challenging the oxygen reactivity of flavoenzymes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin DS, et al. Superoxide dismutase from the eukaryotic thermophile Alvinella pompejana: Structures, stability, mechanism, and insights into amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1534–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross AR, Heyworth PG, Rae J, Curnutte JT. A variant X-linked chronic granulomatous disease patient (X91+) with partially functional cytochrome b. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8194–8200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.8194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rae J, et al. X-Linked chronic granulomatous disease: Mutations in the CYBB gene encoding the gp91-phox component of respiratory-burst oxidase. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1320–1331. doi: 10.1086/301874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picciocchi A, et al. Role of putative second transmembrane region of Nox2 protein in the structural stability and electron transfer of the phagocytic NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28357–28369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shikama K. The molecular mechanism of autoxidation for myoglobin and hemoglobin: A venerable puzzle. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1357–1374. doi: 10.1021/cr970042e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isogai Y, Iizuka T, Shiro Y. The mechanism of electron donation to molecular oxygen by phagocytic cytochrome b558. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7853–7857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.7853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulton DJ. Nox5 and the regulation of cellular function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2443–2452. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson HM, Kawahara T, Nisimoto Y, Smith SM, Lambeth JD. Nox4 B-loop creates an interface between the transmembrane and dehydrogenase domains. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10281–10290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrichon L, et al. Characterization of superoxide overproduction by the D-Loop(Nox4)-Nox2 cytochrome b(558) in phagocytes—Differential sensitivity to calcium and phosphorylation events. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotrosen D, Yeung CL, Leto TL, Malech HL, Kwong CH. Cytochrome b558: The flavin-binding component of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science. 1992;256:1459–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1318579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahan I, Molshanski-Mor S, Pick E. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation by peptides mapping within the dehydrogenase region of Nox2-A “peptide walking” study. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:501–515. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1011507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brosey CA, et al. Defining NADH-driven allostery regulating apoptosis-inducing factor. Structure. 2016;24:2067–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vonrhein C, Blanc E, Roversi P, Bricogne G. Automated structure solution with autoSHARP. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;364:215–230. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-266-1:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cowtan KD. DM: An automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1994;31:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balabin IA, Hu X, Beratan DN. Exploring biological electron transfer pathway dynamics with the Pathways plugin for VMD. J Comput Chem. 2012;33:906–910. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Zundert GC, et al. The HADDOCK2.2 Web Server: User-friendly integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:720–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lensink MF, et al. Prediction of homoprotein and heteroprotein complexes by protein docking and template-based modeling: A CASP-CAPRI experiment. Proteins. 2016;84:323–348. doi: 10.1002/prot.25007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piirilä H, Väliaho J, Vihinen M. Immunodeficiency mutation databases (IDbases) Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1200–1208. doi: 10.1002/humu.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]