The continued emergence of bacteria that are resistant to commonly used antibiotics is a serious danger to public health (1, 2). Policies such as incentivizing the development of new antibiotics (3) and restricting the use of currently effective antibiotics (4) can slow the march of resistant bacteria. Nonetheless, scientific breakthroughs must accompany such actions of governments and international organizations. Recently, a significant advance in the battle against bacteria has been achieved. In PNAS, Okano et al. (5) report the discovery of a new antibiotic that functions via three synergistic modes of action. Importantly, the ability of this agent to attack bacteria using multiple mechanisms dramatically slows the development of resistance.

Vancomycin (Fig. 1) is the prototypical member of the glycopeptide family of antibiotics. Its mode of action involves binding to bacterial cell wall precursor peptides that terminate in a d-Ala-d-Ala sequence. This binding prevents transpeptidase enzymes from cross-linking these strands, thereby impeding the formation of the peptidoglycan protective layer that is critical to the integrity of the bacterial cell wall (6). Despite almost 60 y of clinical use, vancomycin-resistant bacteria have been relatively slow to emerge. However, such organisms are currently viewed as serious threats to human health by both the CDC (7) and the WHO (8). They are able to evade vancomycin by using an ester (i.e., d-Ala-d-Lac) instead of an amide (i.e., d-Ala-d-Ala) as the peptidoglycan precursor. This simple substitution of an oxygen atom for an NH moiety replaces one of the hydrogen bonds that stabilizes the complex between vancomycin and its target with a destabilizing electrostatic repulsion (9, 10).

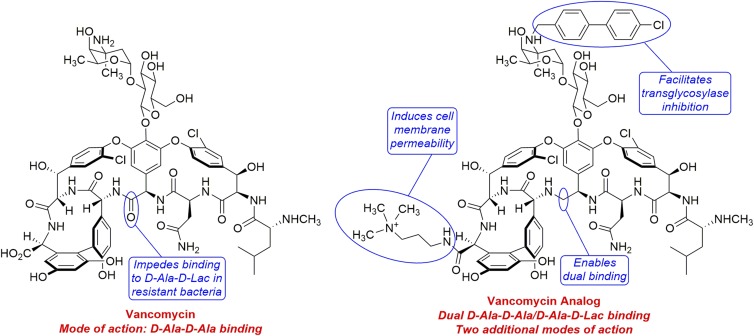

Fig. 1.

Vancomycin and the vancomycin analog created by Okano et al. (5). Vancomycin is susceptible to resistance in bacteria that can use the ester d-Ala-d-Lac instead of the amide d-Ala-d-Ala in construction of their cell walls. The analog combines a binding-pocket modification that enables binding to the cell wall precursors of both vancomycin-sensitive and vancomycin-resistant bacteria with peripheral modifications that permit the agent to attack bacteria by two additional mechanisms. As a result of having three independent yet synergistic modes of action, the analog exhibits negligible susceptibility to acquired resistance.

Previous work from the authors’ group involved removing the carbonyl in vancomycin that clashes with the ester oxygen in d-Ala-d-Lac, resulting in an analog that is potent against both vancomycin-sensitive and vancomycin-resistant bacteria. It should be noted that the deletion of this functional group was not a trivial process, requiring the design and execution of a multistep total synthesis (11). Subsequently, the authors demonstrated that attachment of a (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl (CBP) group onto the amino sugar nitrogen of this binding-pocket–modified vancomycin analog delivered a second-generation analog with increased potency (12). The CBP group is known to enhance the antimicrobial activity of glycopeptide antibiotics, presumably by enabling a second mode of action based on inhibition of the bacterial transglycosylase enzyme (13).

In their current work, Okano et al. (5) developed a third-generation vancomycin analog with an additional peripheral modification that unlocks a third mechanism of action. This compound contains a quaternary ammonium ion that is attached to the C terminus of vancomycin via an amide linkage (Fig. 1). This functional group causes the bacterial cell membrane to become permeable, rendering the analog highly potent against vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (minimum inhibitory concentration = 0.01–0.005 μg/mL). Moreover, the analog exhibits a negligible tendency to induce resistance, as demonstrated by serial exposure at a sublethal level to vancomycin-resistant Enterococci over a period of 50 d. Clearly, it is extremely difficult for bacteria to resist the three distinct yet synergistic mechanisms (i.e., dual d-Ala-d-Ala/d-Ala-d-Lac binding, transglycosylase inhibition, and cell membrane permeabililty) of the third-generation vancomycin analog.

Much remains to be accomplished before this breakthrough can have an impact in the clinic. Okano et al.’s (5) total synthesis route to the vancomycin analog is efficient and suitable for production of the relatively small quantities of material needed to probe its antimicrobial activity. However, it is not amenable to the scale-up that would be required to produce large amounts for clinical trials. Thus, major advances in synthetic methodology are necessary for this work to proceed toward clinical applications. Alternatively, genetic engineering of vancomycin-producing bacteria or biosynthetic enzymes could yield an advanced precursor capable of being transformed into the analog in only a few synthetic steps. This approach will also depend on transformative advances in the ability to manipulate biosynthetic processes.

The third-generation vancomycin analog designed and constructed by Okano et al. (5) incorporates two peripheral structural alterations into a compound possessing a key binding-pocket modification that renders the compound potent against both vancomycin-sensitive and vancomycin-resistant bacteria. Each of these changes introduces an additional mechanism or means of attacking bacteria. These three modes of action operate synergistically, resulting in a highly potent antimicrobial agent. Furthermore, it is extremely difficult for bacteria to simultaneously develop resistance to all three mechanisms. Future work will undoubtedly be focused on the synthetic and biosynthetic breakthroughs that will enable advancement of this exciting compound toward the clinic.

Acknowledgments

The author’s research is supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Grant R15GM114789A1.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page E5052.

References

- 1.WHO . Antimicrobial Resistance. Global Report on Surveillance 2014; WHO; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha MS, Kesselheim AS. Regulatory incentives for antibiotic drug development: A review of recent proposals. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016;24:6446–6451. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laxminarayan R. Antibiotic effectiveness: Balancing conservation against innovation. Science. 2014;345:1299–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1254163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okano A, Isley NA, Boger DL. Peripheral modifications of [Ψ [CH2NH]Tpg4]vancomycin with added synergistic mechanisms of action provide durable and potent antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E5052–E5061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704125114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahne D, Leimkuhler C, Lu W, Walsh C. Glycopeptide and lipoglycopeptide antibiotics. Chem Rev. 2005;105:425–448. doi: 10.1021/cr030103a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017 Biggest threats. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest_threats.html. Accessed May 17, 2017.

- 8.Willyard C. The drug-resistant bacteria that pose the greatest health threats. Nature. 2017;543:15. doi: 10.1038/nature.2017.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh CT. Vancomycin resistance: Decoding the molecular logic. Science. 1993;261:308–309. doi: 10.1126/science.8392747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McComas CC, Crowley BM, Boger DL. Partitioning the loss in vancomycin binding affinity for D-Ala-D-Lac into lost H-bond and repulsive lone pair contributions. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9314–9315. doi: 10.1021/ja035901x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crowley BM, Boger DL. Total synthesis and evaluation of [Ψ[CH2NH]Tpg4]vancomycin aglycon: Reengineering vancomycin for dual D-Ala-D-Ala and D-Ala-D-Lac binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2885–2892. doi: 10.1021/ja0572912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okano A, et al. Total syntheses and initial evaluation of [Ψ[C(═S)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin, [Ψ[C(═NH)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin, [Ψ[CH2NH]Tpg4]vancomycin, and their (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl derivatives: Synergistic binding pocket and peripheral modifications for the glycopeptide antibiotics. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3693–3704. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L, et al. Vancomycin analogues active against vanA-resistant strains inhibit bacterial transglycosylase without binding substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5658–5663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931492100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]