Abstract

Background

Malaria remains a major public health issue in most southern African countries as the disease remains hyper endemic. Burkina Faso continues to face challenges in the treatment of malaria, as the utilization of preventive measures remains low on a national scale. While it has been acknowledged that understanding women’s health-seeking behaviours, perception of malaria and its preventive measures will aid in the control of malaria, there is paucity of information on Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices among women in the reproductive age of 15–49 years in Burkina Faso. This study investigated women’s knowledge of malaria, attitudes towards malaria, and practices of malaria control in order to create a synergy between community efforts and governmental/non-governmental malaria control interventions in Burkina Faso.

Methods

The analysis used data from the 2014 Burkina Faso Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS). In total 8111 women aged between 15–49 years were included in the present study. We assessed women’s knowledge about 1) preventive measures, 2) causes and 3) symptoms of malaria, as well as malaria prevention practices for their children and during pregnancy. The socio-demographic characteristics were considered for Age, Religion, Education, Wealth index, Number of household members, Sex of household head, Household possession of radio, TV and Received antenatal care. Data were analyzed using STATA, version 14. Associations between variables were tested using a Chi-square and logistic regression, with the level of statistical significance set at 95%.

Results

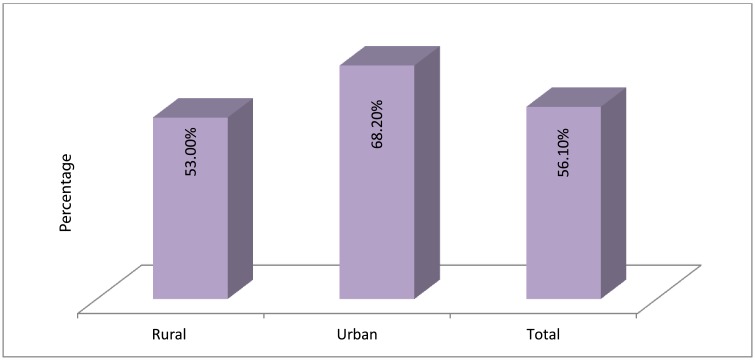

A preponderant proportion of respondents were aged 15–29 years (mean age was 28.63±9.41). About three-quarters of the respondents had no formal education. An estimated two-third of the participants were of Islamic faith, while access to media and behavioural communication were generally poor. The level of knowledge was 53% for rural women and 68.2% for urban dwellers. In sum, there was 56.1% level of accurate knowledge of malaria among women in Burkina Faso. In the multivariable logistic regression, women in rural location had 40% reduction in the odds of having accurate knowledge of malaria when compared to urban women (aOR = 0.60; 95%CI: 0.52–0.68). The educational level was a key factor in the knowledge of malaria. The odds of having accurate knowledge of malaria increased as the educational level increased, hence, women with secondary and higher education had 29% and 93% increase in the odds of having accurate knowledge of malaria when compared to the women without formal education. Results indicate that antenatal care (ANC) services were major sources of information on malaria. Women who reportedly received ANC were 3.9 times more likely to have accurate knowledge of malaria when compared to those who did not utilize skilled ANC services (aOR = 3.90; 95%CI = 3.34–4.56).

Conclusion

The overall knowledge of malaria prevention practices among a large proportion of women was found to be low, which implies that the knowledge about the prevention of malaria should be improved upon by both urban and rural dwellers. There is need for concerted behavioural communication intervention to improve the knowledge of malaria especially for rural dwellers regarding malaria prevention measures, causes and symptoms. Consistent efforts at providing relevant information by health organizations are needed to reduce and control incidences of malaria in the general public.

Background

According to WHO estimates, 212 million global cases of malaria led to 429,000 global deaths in 2015 [1]. The burden was highest in the Sub-Saharan African region where 90% of the malaria cases and 92% of the malaria deaths occurred. Children under 5 years accounted for two thirds of deaths in this region [1]. The disease is severe in pregnant women and children under 5 years old [2,3]. Moreover, approximately 7 million cases of malaria leading to 15,000 deaths were reported in Burkina Faso in 2015 [1]. Of the country’s 16.2 million population, 80% reside in rural areas [4]. The effective treatment of malaria in rural populations in Sub-Saharan Africa is often impeded by poor housing quality, inadequate understanding of malaria causes and transmission, and preference for traditional treatments [5,6].

Food security challenges in Burkina Faso prompted the development of irrigation schemes, which promotes the proliferation of mosquitoes and malaria transmissions [7]. Malaria remains a major public health issue in Burkina Faso as the disease remains hyper endemic and stable [7]. In malaria-stable areas, residents can develop immunity to malaria and become asymptomatic; a vast majority of women with placental malaria are asymptomatic during pregnancy [4]. Persistent asymptomatic malaria infection has been viewed as beneficial to individuals as it reduces the risk of severe infection; however, it can lead to future transmissions [8,9]. Malaria is associated with high risk factors for maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, such as maternal anemia, preterm delivery and placental malaria, which leads to low birth weight babies [8,10,11].

Burkina Faso’s national malaria control program promotes the use of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITN) through their free distribution. The program also provides available and accessible artemisinin-based combined therapy (ACT) and free intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) for vulnerable groups particularly pregnant women. Furthermore, the country aligned strategies for malaria prevention with WHO’s recommendation and adopted the seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) program for children under 5 years [4,7]. Indoor residual spraying (IRS) was also included as an additional preventive measure. Burkina Faso continues to face challenges in the treatment of malaria as the utilization of preventive measures remains low on a national scale [12,13]. Less than 1% of the population used IRS in 2014 and despite the equity in ITN possession among households, 25% of children were not sleeping under ITNs in 2014 [6]. Furthermore, there is a preference for self-treatment using local herbs, which leads to the delay in treatment at health facilities [4,14].

The goal of WHO to end the malaria epidemic by 2030 lies in its commitment to “continue to invest in changing people’s behaviour” [15]. A gendered approach to understanding the knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of malaria and its control is necessary because gender norms influence labour, leisure and sleeping patterns, which invariably impacts exposures to mosquitoes. There are also gender dynamics in treatment-seeking behaviours and authority within households [16–19]. Women in particular are vulnerable to the disease especially during pregnancy. They are also responsible for home-based management of malaria among children under 5 years of age, who are highly vulnerable to malaria [20,21]. Women also serve as role models for their families in raising awareness and participating in malaria prevention and control.

The awareness of malaria vectors, mosquito behavioural pattern (biting and resting times) and breeding sites have been associated with the severity of malaria [22]. A study in Tanzania, with a majority of female participants, showed a poor understanding of mosquito behaviour pattern and breeding sites in an area with a high prevalence of malaria [23]. Little or no benefit of malaria control programs have been reported in areas where there is a lack of awareness of malaria control strategies [24–27]. Furthermore, women in the south-central district of Ethiopia were reported to have a high level of general knowledge on malaria, such as symptoms and treatment; however, their knowledge of causes of malaria and preventive measures were generally low [28]. Consequently, the use of preventive measures against malaria was low in households within the district [28]. Moreover, local concepts of illness affect choices regarding malaria treatment. In Burkina Faso, mothers' perception and interpretation of disease were reported to influence treatment choices for malaria [29]. Some manifestations of malaria were misdiagnosed by traditional methods and they were often self-treated at home. This shows that biomedical concept of malaria is not adequately understood. Moreover, traditional treatment of malaria delays effective biomedical treatment and can be fatal [29].

While it has been acknowledged that understanding women’s health-seeking behaviours, perception of malaria and its preventive measures will aid in the control of malaria, there is paucity of information on KAP among women in the reproductive age of 15–49 years in Burkina Faso. Therefore, the objective of this study is to understand women’s knowledge, attitudes and practices of malaria and its control in order to create a synergy between community efforts and governmental/nongovernmental malaria control interventions in Burkina Faso.

Methods

Study area and survey

This study used secondary data from the 2014 Burkina Faso Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS). We accessed the data from MEASURE DHS database at http://dhsprogram.com/what-we-do/survey/survey-display-481.cfm. The survey was conducted by the Burkina Faso National Statistical Agency as part of the International Demographic and Health Survey program known as MEASURE DHS, which is currently active in 90 countries and conducted under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) with the technical assistance of ICF International, based in the USA. The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) are free, public datasets, though researchers must register with MEASURE DHS and submit a request before access to DHS data is granted. This data request system ensures that all users understand and agree to basic data usage ethics standards.

The Burkina Faso Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS) 2014 is a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey following RBM Monitoring and Evaluation Reference Group (MERG) guidelines. The MIS was conducted from 29 September to 28 November 2014 and provides information on the knowledge and practice of malaria prevention in Burkina Faso, and is part of phase 7 of the Demographic and Health Survey series (DHS). In brief, 8111 women ages 15–49 from 6,448 households were successfully interviewed. The details of the survey and sampling procedures have been described in the final report [30].

Selection of variables

In this study, we assessed women’s knowledge about 1) preventive measures, 2) causes and 3) symptoms of malaria, as well as malaria prevention practices for their children and during pregnancy. The MIS 2014 included a number of basic questions for this purpose which are described below:

Knowledge about preventive measures: 1) Sleeping under a mosquito net, 2) Sleeping under a mosquito net impregnated with insecticide, 3) Using insecticide sprays, creams, lotions, 4) Taking preventative medications, 5) Using insecticide coils, 6) Decoction/plant juice/Root to drink as a preventive measure, 7) Making sure surroundings are clean, 8) Using a coil smoke, 9) Covering the body.

Knowledge about causes: 1) Mosquito bite, 2) Heavy oil consumption, 3) Work-related fatigue, 4) Insufficient sleeping, 5) Direct exposure to sunlight, 6) Consumption of mangoes / sweet fruits 7) Milk consumption 8) Drinking dirty water.

Knowledge about common symptoms of malaria: 1) Fever 2) Vomiting and lack of appetite 3) High temperature with convulsions 4) High temperature with fainting 5) Persistent fever 6) Convulsions 7) Jaundice 8) Headache 9) Urine.

The socio-demographic characteristics considered were: Age (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 44+), Religion (Islam, Christian, Other), Education (No education, Primary, Secondary, Higher), Wealth index (Poorest, Poorer, Middle, Richer, Richest), Number of household (HH) members (6, >6), Sex of household head (Male, Female), Household possession of radio (No, Yes), TV (No, Yes), Received antenatal care.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted with STATA version 14. Basic social and demographic characteristics were presented as percentages and frequencies. Analyses were stratified by area of residence (urban/rural) due to the influence of neighbourhood status on health knowledge, self-efficacy and practice. Chi-square tests were employed to assess any significant difference in knowledge of prevention, causes, symptoms, and practices between urban and rural areas. Logistic regression was used to examine the factors associated with knowledge of malaria among women in Burkina Faso. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Ethics statement

Before each interview, all participants gave informed consent to take part in the survey. The DHS Program maintains strict standards for ensuring data anonymity and protecting the privacy of all participants. ICF International ensures that the survey complies with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects, whilst the host country ensures that the survey complies with local laws and norms. Further approval for this study was not required since the data is secondary and is available in the public domain. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available at: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Results

Descriptive analysis

A total of 8,111 women aged 15 to 49 years were included in the study. Basic socio-demographic characteristics of the participants were presented as frequencies and percentages in Table 1. Mean age was 28.63 years (SD 9.41). Table 1 shows that most of the women were aged 15 to 19 years (21.1%), prominent faith was Islam (64.3%) and about two-third had no formal education (71.3%). About half of the respondents had low economic status. A majority of the households had more than six members (57.7%). Male-headed households were predominant (90.4%) in the sample. Approximately three-fifths of the women had a radio (61.1%) and only about one-fifth had television (20.9%). The uptake of antenatal care (ANC) services was low, only about 14% of the women reported receiving any ANC. There was a significant association between place of residence and socio-economic and maternal factors in certain variables among women.

Table 1. Characteristics of the women (Burkina Faso Malaria Indicator Survey 2014).

| Variable | Total | Urban | Rural | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (28.63±9.41) | n = 8,111 | % | 20.6 | 79.4 | 0.128 |

| 15–19 | 1714 | 21.1 | 22.1 | 20.9 | |

| 20–24 | 1411 | 17.4 | 15.8 | 17.8 | |

| 25–29 | 1417 | 17.5 | 16.4 | 17.7 | |

| 30–34 | 1197 | 14.8 | 14.1 | 14.9 | |

| 35–39 | 1065 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 12.9 | |

| 40–44 | 738 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 8.9 | |

| 45–49 | 569 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 6.8 | |

| Religion | <0.001* | ||||

| Islam | 5212 | 64.3 | 65.1 | 64.0 | |

| Christianity | 2222 | 27.4 | 33.0 | 25.9 | |

| Other | 677 | 8.3 | 1.9 | 10.0 | |

| Education | 0.069 | ||||

| No education | 5781 | 71.3 | 69.0 | 71.9 | |

| Primary | 1109 | 13.7 | 14.7 | 13.4 | |

| Secondary | 1154 | 14.2 | 15.2 | 14.0 | |

| Higher | 67 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.7 | |

| Wealth index | 0.017* | ||||

| Poorest | 1630 | 20.1 | 23.1 | 19.3 | |

| Poorer | 1678 | 20.7 | 19.8 | 20.9 | |

| Middle | 1767 | 21.8 | 21.1 | 22.0 | |

| Richer | 1734 | 21.4 | 21.0 | 21.5 | |

| Richest | 1302 | 16.1 | 15.0 | 16.3 | |

| No. of HH members | 0.331 | ||||

| 6 | 3428 | 42.3 | 41.8 | 42.4 | |

| >6 | 4683 | 57.7 | 58.2 | 57.6 | |

| Sex of HH head | <0.001* | ||||

| Male | 7335 | 90.4 | 92.6 | 89.9 | |

| Female | 776 | 9.6 | 7.4 | 10.1 | |

| HH has radio | <0.001* | ||||

| No | 3066 | 37.9 | 28.8 | 40.1 | |

| Yes | 4944 | 61.1 | 71.2 | 59.9 | |

| HH has TV | <0.001* | ||||

| No | 6314 | 78.1 | 38.9 | 87.9 | |

| Yes | 1687 | 20.9 | 61.1 | 12.1 | |

| Received ANC | 0.005* | ||||

| No | 6977 | 86.0 | 88.0 | 85.5 | |

| Yes | 1134 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 14.5 | |

*significant at p<0.05; N.B. ANC was counted as ‘Yes’ when offered by health professionals e.g. doctor, nurse or community health worker.

The assessment of accurate knowledge of malaria prevention, causes and symptoms are shown in Table 2. A majority of the women (97.4%) and over 80% of the women reported that sleeping under a mosquito net and sleeping under insecticide treated net respectively, are the best practices to prevent malaria. Furthermore, a very low proportion of the women opined that: using insecticide sprays, creams and lotions (6.1%), taking preventative medications (6.4%), insecticide coils (4.5%), drinking plant juice/root (5.9%), coil smoke (4.9%) and covering the body (8.7%) were the best preventive measures. About one-fifth reported that keeping the surrounding clean is the best preventive measure.

Table 2. Knowledge about best preventive measures, main causes and symptoms of malaria (n = 8111).

| Item | Rural (%) | Urban (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best way to prevent malaria | |||

| Sleep under a mosquito net | 97.2 | 98.0 | 97.4 |

| Sleep under a mosquito net impregnated with insecticide | 80.6 | 80.8 | 80.7 |

| Using insecticide spray, creams, lotions | 94.4 | 92.3 | 93.9 |

| Take preventive medications | 93.3 | 94.5 | 93.6 |

| Using insecticide coil | 95.4 | 96.0 | 95.5 |

| Decoction/plant juice/root to drink as a preventive | 93.9 | 94.8 | 94.1 |

| Making sure surroundings are clean | 80.4 | 77.5 | 79.8 |

| Using a coil smoke | 95.1 | 95.0 | 95.1 |

| Cover the body | 91.1 | 92.3 | 91.3 |

| Main cause of malaria | |||

| Mosquito bite | 81.4 | 100.0 | 85.2 |

| Heavy oil consumption | 98.1 | 96.2 | 97.7 |

| Work-related fatigue | 96.5 | 97.4 | 96.7 |

| Insufficient sleeping | 98.9 | 99.9 | 99.1 |

| Direct exposure to sunlight | 92.8 | 97.3 | 93.8 |

| Consumption of mangoes/sweet fruits | 97.3 | 99.7 | 97.8 |

| Milk consumption | 99.0 | 99.9 | 99.1 |

| Dirty water | 92.8 | 54.0 | 84.9 |

| Symptoms of malaria | |||

| Fever | 76.7 | 100.0 | 81.5 |

| Vomiting, lack of appetite | 46.8 | 84.3 | 54.5 |

| High temperature with convulsion | 94.1 | 94.5 | 94.2 |

| High temperature with fainting | 97.1 | 99.0 | 97.5 |

| Persistent fever | 96.3 | 99.7 | 97.0 |

| Convulsion | 92.2 | 98.4 | 93.5 |

| Jaundice | 87.4 | 97.7 | 89.5 |

| Headache | 74.8 | 59.2 | 71.6 |

| Urine | 98.5 | 98.1 | 98.4 |

In addition, a majority of the women (85.2%) knew that mosquito bites could cause malaria. While low proportion accepted that heavy oil consumption (2.3%), work-related fatigue (3.3%), insufficient sleeping (0.9%), exposure to sunlight (6.2%), consumption of certain fruits (2.2%), milk (0.9%), and dirty water (15.1%) can be the main cause of malaria.

More so, a majority of the women identified fever (81.5%), vomiting (54.5%) as the main symptoms of malaria. About 10% reported jaundice and 28.4% headache as the common symptoms. Those who reported other physical symptoms, such as fainting, convulsion, and urinary problems were comparatively lower.

On the malaria prevention practices, out of 4,656 women, 20.4% reported not using any net at all and 77.9% reported using only insecticide treated nets for children during the night before the survey as shown in Table 3. Regarding the use antimalarial drugs for febrile illnesses during malaria, amodiaquine was the commonest one (21.6%) followed by fansidar, quinine and chloroquine. A majority of the women (84.7%) reported taking antimalarial drugs during pregnancy. No significant different was observed in these practices between urban and rural areas except for taking fansidar.

Table 3. Prevalence of malaria prevention practices (Burkina Faso Malaria Indicator Survey 2014).

| Types of practices | Total | Urban (%) | Rural (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of mosquito bed net(s) child slept under last night(n = 4645) | 0.599 | |||

| No net | 20.4 | 20.9 | 20.4 | |

| Only treated nets | 77.9 | 77.8 | 77.9 | |

| Only untreated nets | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

| Fansidar taken for fever/cough (n = 2032) | 0.012* | |||

| No | 88.6 | 85.2 | 89.5 | |

| Yes | 11.4 | 14.8 | 10.5 | |

| Chloroquine taken for fever/cough(n = 2032) | 0.379 | |||

| No | 99.0 | 98.7 | 99.0 | |

| Yes | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | |

| Amodiaquine taken for fever/cough(n = 2032) | 0.397 | |||

| No | 78.4 | 79.0 | 78.2 | |

| Yes | 21.6 | 21.0 | 21.8 | |

| Quinine taken for fever/cough(n = 2032) | 0.309 | |||

| No | 98.8 | 98.5 | 98.9 | |

| Yes | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.1 | |

| During this pregnancy did you take medicine to prevent malaria? (n = 5130) | 0.427 | |||

| No | 15.3 | 14.8 | 15.4 | |

| Yes | 84.7 | 85.2 | 84.6 |

*significant at p<0.001

Fig 1 showed that the level of the knowledge of malaria preventive measures, causes and symptoms was low. The level of knowledge of malaria for rural dwellers was at 53%, while the urban dwellers had a higher level of knowledge at 68.2%. In sum, there was 56.1% level of the accurate knowledge of malaria preventive measures, causes and symptoms among women of reproductive age in Burkina-Faso.

Fig 1. Level of accurate knowledge of malaria.

The association between the level of knowledge on malaria and socio-demographic and maternal factors was tested using Chi-squared bivariate analysis to determine the variables that will be included in the logistic regression model. Results from Table 4 revealed that place of residence, religion, educational attainment; ANC and being in possession of radio or television had signification association with the level of knowledge. On the contrary, age, wealth index, sex of household head and source of antimalarial drug during pregnancy, did not show any significant association with the level of knowledge among women aged 15–49 years.

Table 4. Socio-demographic and maternal characteristics associated with knowledge of malaria (n = 8111).

| Variable | Knowledge of malaria | Total | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accurate | Poor | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 15–19 | 1005(58.6) | 709(41.4) | 1714(100.0) | 0.175 |

| 20–24 | 794(56.3) | 617(43.7) | 1411(100.0) | |

| 25–29 | 760(53.6) | 657(46.4) | 1417(100.0) | |

| 30–34 | 672(56.1) | 525(43.9) | 1197(100.0) | |

| 35–39 | 596(56.0) | 469(44.0) | 1065(100.0) | |

| 40–44 | 418(56.6) | 320(43.4) | 738(100.0) | |

| 45–49 | 308(54.1) | 261(45.9) | 569(100.0) | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 1139(68.2) | 530(31.8) | 1669(100.0) | <0.001* |

| Rural | 3414(53.0) | 3028(47.0) | 6442(100.0) | |

| Religion | ||||

| Islam | 3014(57.8) | 2198(42.2) | 5212(100.0) | 0.001* |

| Christianity | 1539(53.1) | 1360(46.9) | 2899(100.0) | |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| No formal education | 3161(54.7) | 2620(45.3) | 5781(100.0) | <0.001* |

| Primary | 635(57.3) | 474(42.7) | 1109(100.0) | |

| Secondary | 711(61.6) | 443(38.4) | 1154(100.0) | |

| Higher | 46(68.7) | 21(31.3) | 67(100.0) | |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorest | 905(55.5) | 725(44.5) | 1630(100.0) | 0.914 |

| Poorer | 939(56.0) | 739(44.0) | 1678(100.0) | |

| Middle | 1009(57.1) | 758(42.9) | 1767(100.0) | |

| Richer | 972(56.1) | 762(43.9) | 1734(100.0) | |

| Richest | 728(55.9) | 574(44.1) | 1302(100.0) | |

| Sex of household head | ||||

| Male | 4099(55.9) | 3236(44.1) | 7335(100.0) | 0.162 |

| Female | 454(58.5) | 322(41.5) | 776(100.0) | |

| Radio | ||||

| Yes | 3275(64.9) | 1770(35.1) | 5045(100.0) | <0.001* |

| No | 1278(41.7) | 1788(58.3) | 3066(100.0) | |

| Television | ||||

| Yes | 1214(67.6) | 583(32.4) | 1797(100.0) | <0.001* |

| No | 3339(52.9) | 2975(47.1) | 6314(100.0) | |

| Received ANC | ||||

| Yes | 896(79.0) | 238(21.0) | 1134(100.0) | <0.001* |

| No | 3657(52.4) | 3320(47.6) | 6977(100.0) | |

| Source of antimalarial during pregnancy | ||||

| Antenatal visit | 1910(55.5) | 1533(44.5) | 3443(100.0) | 0.895 |

| Another facility visit | 10(52.6) | 9(47.4) | 19(100.0) | |

| Other source | 5(62.5) | 3(37.5) | 8(100.0) | |

*significant at p<0.05

Results from Table 5 revealed that women in rural locations had 40% reduction in the odds of having accurate knowledge of malaria when compared to the urban women (aOR = 0.60; 95%CI: 0.52–0.68). For religion, it was reported that Christianity had 14% reduction in the odds of having accurate knowledge when compared to Islam (aOR = 0.86; 95%CI: 0.78–0.95). Educational attainment was a factor of the knowledge of malaria. The odds of having accurate knowledge of malaria increased as the educational level increased; hence, secondary and higher education had 29% and 93% increase in the odds of having accurate knowledge of malaria when compared to the women without formal education. Furthermore, respondents who had radio and television were 2.59 times and 1.22 times more likely to have accurate knowledge of malaria when compared to those who have none. It was also evident that antenatal care services teach women about malaria as women who reportedly utilized ANC services were 3.90 times more likely to have accurate knowledge of malaria when compared to those who did not utilize skilled ANC services (aOR = 3.90; 95%CI = 3.34–4.56).

Table 5. Multivariable analysis of the factors associated with knowledge of malaria.

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio(95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban(ref) | 1.00 | |

| Rural | 0.60(0.52–0.68) | <0.001* |

| Religion | ||

| Islam(ref) | 1.00 | |

| Christianity | 0.86(0.78–0.95) | 0.003* |

| Highest level of education | ||

| No formal education(ref) | 1.00 | |

| Primary | 1.07(0.93–1.23) | 0.344 |

| Secondary | 1.29(1.13–1.48) | <0.001* |

| Higher | 1.93(1.13–3.32) | 0.017* |

| Radio | ||

| No(ref) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 2.59(2.35–2.86) | <0.001* |

| Television | ||

| No(ref) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.22(1.07–1.39) | 0.003* |

| Received ANC | ||

| No (ref) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.90(3.34–4.56) | <0.001* |

*significant at p<0.05; Pseudo R-squared = 0.08

Discussion

Knowledge about Malaria was analysed across four domains: prevention, causes, symptoms and preventive practises pursued. In the domain of prevention, majority of the women (97.4) reported that sleeping under a mosquito net and most of the women (80%) reported that sleeping under an insecticide treated net is the best practice to prevent malaria. A small proportion of women affirmed that using other preventive measures like insecticide sprays, using creams, lotions or keeping the surrounding clean can help to prevent transmission of malaria. Overall it can be stated that the knowledge about prevention, causes and symptoms of malaria was slightly above average among the respondents. This finding is similar to findings from previous studies where knowledge about preventive measures was found to be relatively high [31, 32]. One study interestingly reported that although the knowledge of preventive measures was high, it does not translate into preventive practices [31]. This was an important finding during our analysis and will be further discussed in detail along with the preventive practices pursued among women. The finding about better knowledge of preventive practices might be illustrative of a positive impact of behavioural communication techniques used toward malaria control.

In general, there was a difference in the knowledge of malaria between rural and urban locations. For the knowledge items, urban women were more aware that malaria could be caused by mosquito bites. Moreover, rural dwellers indicated more of the unrelated factors for malaria, such as heavy oil consumption, work related fatigue, insufficient sleeping, and exposure to sunlight, consumption of certain fruits, milk and dirty water as causes of malaria. The findings may be presumed to be related to a myriad of other factors, such as level of education in rural areas and access to media or behavioural communication at ANC. For example, one study reported significant association between level of education and the knowledge about transmission of malaria in rural areas [33]. Overall, previous studies have reported findings similar to the current study in that, urban areas have significantly higher knowledge about the causes of malaria [33, 34].

Fever and vomiting were identified as the most common symptoms of malaria. Nearly 10% and 28% reported symptoms such as jaundice and headache respectively. However, it is noteworthy that respondents from urban areas were more knowledgeable than those from rural areas and the difference was statistically significant. This finding is again consistent with findings from previous studies [31, 32, 33, 34]. The findings suggest that except for the knowledge about prevention of malaria, the urban areas fared better in terms of knowledge about causes and symptoms of malaria than the rural areas. Notably, rural participants had better knowledge of several symptoms (with few exceptions), especially that of jaundice. Consistent with the findings from a previous study, the current study also inclines to the conclusion that there is dearth of information percolating to the rural areas in terms of control strategies for malaria. This dearth may be directly related to the communication strategies employed and/or could be consequential to a number of related factors like education level, local cultural practices, media exposure and others. Interestingly, the message about preventive methods is reaching the rural population, however, that about causes and symptoms is not. This is an area that needs further research.

Another aspect of the current study is studying the preventive practices pursued. Knowing about the prevention methods, causes and symptoms of malaria is one thing and employing preventive practices is another. For example, 97.4% (n = 8111) of women in the current study indicated knowing that sleeping under a net is the best practice to prevent malaria. Despite this, about one-fifth of the women (20.4%, n = 4645) reported not using any bed net for children during the night before the survey. This is true for both urban and rural areas. So the messages for malaria control which appeared well percolated in both urban and rural areas are still not pragmatically useful. Similarly, one study reported that generic community education programs may not be as effective in endemic areas [35]. This indicates the need for more integrated approaches which target not only communicating the current best practices in malaria prevention and control but also customising these efforts to the local cultural practices which prevent the pragmatic uptake of such messages. This remains true for both urban and rural areas.

Strength and limitations

This study comprised of a nationally representative large dataset. More so, there was high response among the study participants. Nonetheless, the current study has certain limitations in terms of the availability of data. The current study relying on the data available in public domain had no control over the quality and type of data. One potentially conflicting observation was the high prevalence of antimalarial drug use during pregnancy despite the fact that the rate of ANC attendance was notably low. This is perhaps due to the presence of traditional service providers who are usually not considered when measuring the prevalence of skilled care providers for reproductive health. Finally, the prevalence of utilization of antimalarial drugs could be higher had a broader range of medications available in the market be considered [36].

Conclusion

The findings indicate that the general knowledge of malaria could be improved upon by both urban and rural dwellers. There were statistically significant differences observed between urban and rural areas in terms of the knowledge about the prevention, causes and symptoms of malaria with the urban areas faring better than the rural areas. Also, there were factors, such as level of education, place of residence, access to the media, ANC and religion, that were associated with the level of knowledge of malaria. Overall, it can be stated that there is limited knowledge of the best practices in malaria prevention and control. The knowledge of malaria must be improved and translated into good practices to enhance prevention and control. Several factors, such as education level, exposure to the media, ANC, religion and place of residence, need to be integrated into the current generalized communication strategies employed by the ministry of health to improve the prevention and control of malaria. There is need to conduct more evidence-based research on the role of socio-cultural practices among women toward malaria prevention and control.

Acknowledgments

We express our most sincere thanks to The DHS Program for providing data for this study.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Artemisinin-based Combined Therapy

- IRS

Indoor Residual Spraying

- ITN

Insecticide Treated bed Nets

- KAP

Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices

- SMC

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention

Data Availability

This study used secondary data from the 2014 Burkina Faso Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS). We accessed the data from MEASURE DHS database at http://dhsprogram.com/what-we-do/survey/survey-display-481.cfm.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Malaria Report. 2016.

- 2.Pell C, Straus L, Andrew EVW, Meñaca A, Pool R. Social and cultural factors affecting uptake of interventions for malaria in pregnancy in Africa: A systematic review of the qualitative research. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuma J, Okungu V, Ntwiga J, Molyneux C. Towards achieving Abuja targets: identifying and addressing barriers to access and use of insecticides treated nets among the poorest populations in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2010;10: 137 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program. A Documentation of Malaria Program Implementation in Burkina Faso. 2013; 54. http://www.mchip.net/sites/default/files/Malaria_Program_Implementation_in_BFaso.pdf

- 5.Maslove DM, Mnyusiwalla A, Mills EJ, McGowan J, Attaran A, Wilson K. Barriers to the effective treatment and prevention of malaria in Africa: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9: 26 doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tusting LS, Bottomley C, Gibson H, Kleinschmidt I, Tatem AJ, Lindsay SW, et al. Housing Improvements and Malaria Risk in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multi-Country Analysis of Survey Data. PLOS Med. 2017;14: e1002234 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hien AS, Sangaré I, Coulibaly S, Namountougou M, Paré-toé L, Ouédraogo AG, et al. Parasitological Indices of Malaria Transmission in Children under Fifteen Years in Two Ecoepidemiological Zones in Southwestern Burkina Faso. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1507829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen I, Clarke SE, Gosling R, Hamainza B, Killeen G, Magill A, et al. “Asymptomatic Malaria”: A Chronic and Debilitating Infection That Should Be Treated. PLoS Med. 2016;13: 1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doolan DL, Dobaño C, Baird JK. Acquired immunity to Malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22: 13–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00025-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidima WB. Syncytiotrophoblast Functions and Fetal Growth Restriction during Placental Malaria. 2015;2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgella S, Fievet N, Huynh BT, Ibitokou S, Hounguevou G, Affedjou J, et al. Impact of pregnancy-associated malaria on infant malaria infection in southern Benin. PLoS One. 2013;8: 1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diboulo E, Sie A, Vounatsou P. Assessing the effects of malaria interventions on the geographical distribution of parasitaemia risk in Burkina Faso. Malar J. BioMed Central; 2016;15: 228 doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1282-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaya Bocoum F, Belemsaga D, Adjagba A, Walker D, Kouanda S, Tinto H. Malaria prevention measures in Burkina Faso: distribution and households expenditures. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13: 108 doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0108-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okwundu C, Nagpal S, Musekiwa A, Sinclai D. Home-or community-based programmes for trating malaria (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev Home-. 2013; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009527.pub2 www.cochranelibrary.com [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO WHO. Malaria is no longer leading cause of death among children in sub-Saharan Africa [Internet]. 2015 [cited 23 Mar 2017]. http://www.afro.who.int/en/media-centre/pressreleases/item/8920-malaria-is-no-longer-leading-cause-of-death-among-children-in-sub-saharan-africa.html

- 16.World Health Organization. Gender, Health, and Malaria. Health Policy (New York). 2007;52: 267–292. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-90355-2 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diiro GM, Affognon HD, Muriithi BW, Wanja SK, Mbogo C, Mutero C. The role of gender on malaria preventive behaviour among rural households in Kenya. Malar J. BioMed Central; 2016;15: 14 doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-1039-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins R, Omollo R, Ongecha M, Sifuna P, Othieno C, Ongeri L, et al. Prevalence of malaria parasites in adults and its determinants in malaria endemic area of Kisumu County, Kenya. Malar J. BioMed Central; 2015;14: 263 doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0781-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garley A, Patton E, Eckert E, Negroustoueva S. Gender differences in insecticide treated nets (ITN) use after a universal free distribution campaign in Kano State, Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87: 117 Available: http://www.ajtmh.org/content/87/5_Suppl_1/75.full.pdf+html%5Cnhttp://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed10&NEWS=N&AN=7104102322764301 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutegeki E, Chimbari MJ, Mukaratirwa S. Assessment of individual and household malaria risk factors among women in a South African village. Acta Trop. Elsevier B.V.; 2016; doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto SS, Souares A, Sié A, Sauerborn R. Does recent contact with a health care provider make a difference in malaria knowledge? J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56: 414–420. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Killeen GF. Characterizing, controlling and eliminating residual malaria transmission. Malar J. 2014;13: 330 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathania MM, Kimera SI, Silayo RS. Knowledge and awareness of malaria and mosquito biting behaviour in selected sites within Morogoro and Dodoma regions Tanzania. Malar J. BioMed Central; 2016;15: 287 doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1332-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou G, Afrane YA, Vardo-Zalik AM, Atieli H, Zhong D, Wamae P, et al. Changing patterns of malaria epidemiology between 2002 and 2010 in western kenya: The fall and rise of malaria. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okiro EA, Kazembe LN, Kabaria CW, Ligomeka J, Noor AM, Ali D, et al. Childhood Malaria Admission Rates to Four Hospitals in Malawi between 2000 and 2010. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, Kakuru A, Arinaitwe E, Greenhouse B, Tappero J, et al. Increasing incidence of malaria in children despite insecticide-treated bed nets and prompt anti-malarial therapy in Tororo, Uganda. Malar J. 2012;11: 435 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louis VR, Schoeps A, Tiendrebéogo J, Beiersmann C, Yé M, Damiba MR, et al. An insecticide-treated bed-net campaign and childhood malaria in Burkina Faso. Bull World Heal Organ. 2015;93: 750–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.147702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deressa W, Ali A. Malaria-related perceptions and practices of women with children under the age of five years in rural Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2009;9: 259 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beiersmann C, Sanou A, Wladarsch E, De Allegri M, Kouyaté B, Müller O. Malaria in rural Burkina Faso: local illness concepts, patterns of traditional treatment and influence on health-seeking behaviour. Malar J. 2007;6: 106 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie. Enquête sur les Indicateurs du Paludisme (EIPBF) 2014

- 31.Rupashree S, Jamila M, Sanjay S, Ukatu VE. Knowledge, attitude and practices on malaria among the rural communities in Aliero, Northern Nigeria. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2014; 3(1) 39–44. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.130271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Astatkie A. Knowledge and practice of malaria prevention methods among residents of Arba Minch Town and Arba Minch Zuria District, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2011December;20(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazigo HD, Obasy E, Mauka W, Manyiri P, Zinga M, Kweka EJ, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices about Malaria and Its Control in Rural Northwest Tanzania. Malaria Research and Treatment. 2010;2010:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dhawan G, Joseph N, Pekow PS, Rogers CA, Poudel KC, Bulzacchelli MT. Malaria-related knowledge and prevention practices in four neighbourhoods in and around Mumbai, India: a cross-sectional study. Malaria Journal. 2014;13(1):303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forero DA, Chaparro PE, Vallejo AF, Benavides Y, Gutiérrez JB, Arévalo-Herrera M, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of malaria in Colombia. Malaria Journal. 2014;13(1):165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tipke Maike, Diallo Salou, Coulibaly Boubacar et al. Substandard anti-malarial drugs in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2008; 7: 95 doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study used secondary data from the 2014 Burkina Faso Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS). We accessed the data from MEASURE DHS database at http://dhsprogram.com/what-we-do/survey/survey-display-481.cfm.