Abstract

Background:

In spite of the high rate of overuse injuries in ballet dancers, no studies have investigated the prevalence of overuse injuries in professional dancers by providing specific diagnoses and details on the differences in the injuries sustained as a function of age and/or years of professional practice.

Hypothesis:

Overuse injuries are the most prevalent injuries in ballet dancers. Professional ballet dancers suffer different types of injuries depending on their age and years of professional practice.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Methods:

This descriptive epidemiological study was carried out between January 1, 2005, and October 10, 2010, regarding injuries sustained by professional dancers belonging to the major Spanish ballet companies practicing classical, neoclassical, contemporary, and Spanish dance. The sample was distributed into 3 different groups according to age and years of professional practice. Data were obtained from the specialized medical care the dancers received from the Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery Service at Fremap in Madrid. The dependent variable was the study of the injury.

Results:

A total of 486 injuries were identified over the study period, with overuse injuries being the most common etiology (P < .0001); these injuries were especially prevalent in junior professional dancers practicing classical ballet and veteran dancers practicing contemporary ballet (P = .01). Specifically, among other findings, stress fractures of the base of the second metatarsal (P = .03), patellofemoral syndrome, and os trigonum syndrome were more prevalent among junior professionals (P = .04); chondral injury of the knee in senior professionals (P = .04); and cervical disc disease in dancers of intermediate age and level of experience.

Conclusion:

Overall, overuse injuries were more prevalent in younger professionals, especially in women. This finding was especially true for the more technical ballet disciplines. On the other hand, in the athletic ballet disciplines, overuse lesions occurred mainly in the more senior professionals.

Clinical Relevance:

This study provides specific clinical diagnoses obtained through physical examination as well as details on the different injury types sustained as a function of age and/or years of professional practice, an important aspect for ballet and sports practice in general.

Keywords: overuse injuries, ballet injuries, professional dancers, age-related differences in injury types

There are 2 kinds of injuries that affect the musculoskeletal system of both ballet dancers and athletes in general31: traumatic injuries and nontraumatic or overuse injuries. Overuse injuries in ballet dancers can be a result of poor planning of training sessions or rehearsals, deficient technical execution, or frequent performance of repetitive movements without sufficient recovery time.28,30 Individual anatomic characteristics and exposure to different environmental conditions (footwear, surface) can also contribute to the onset of overuse injuries. In addition, dancers lack the physical conditioning required for the demanding practice schedule. Finally, eating disorders, which are not uncommon in female dancers, can contribute to the development of stress fractures.§

Overuse injuries in dancers typically present as pain. Dancers sustaining these injuries often tend to underestimate their significance and frequently fail to allow for recovery from fatigue.22 In ballet, the main etiologic factor leading to overuse injuries is the alteration of the biomechanical conditions of the exercise.4 Development by the athlete of a good technique that is adapted to his or her biomechanical condition is one of the most effective ways of preventing these injuries. On the other hand, an insufficient or inadequate technique is likely to promote the occurrence of injuries.

There are sex-specific differences between male and female ballet dancers. Males are usually expected to meet tougher athletic requirements, whereas females tend to have more demanding technical requirements. Additionally, there are specific gestures typical of women (points, forced dehors) or men (portées, wider jumps), which might be a factor in the different injury profiles seen between the sexes.17,31

Regarding the difference between the ballet disciplines,10,12,13,18,29,32 it must be said that the most popular types in Spain are classical, contemporary, neoclassical, and Spanish ballet. In all of them, a thorough knowledge and flawless execution of the classical ballet technique are mandatory. Classical ballet is the most formal and technically demanding of the ballet styles. In contemporary ballet, movements are less rigidly formalized, with fewer rules and limitations. Neoclassical ballet constitutes a happy medium between the structured formality of classical ballet and the freedom of movement of contemporary ballet. Finally, Spanish ballet is a blend between classical ballet and Spanish folklore and is characterized, among other things, by high-heeled shoes and profuse heel tapping in most performances.31,32 Although most professional dancers practice a major ballet discipline, it is not uncommon for dancers to cross over to another discipline during the season.

Considering that skill is usually acquired through experience, and that talent or an innate ability to perform a certain activity are not always present, it would seem logical that the prevalence of overuse injuries related to improvement of technique should be higher among younger professional dancers. These dancers would be expected to need more repetitions to achieve proficiency in their performance. As more dexterity is gained, the prevalence of overuse injuries should decrease. In contrast, the prevalence of overuse injuries related to joint mechanical overload arising from long-term exposure to the physical rather than technical requirements of any athletic activity should progressively increase as exposure to such requirements also increases with the years.

We are not aware of any epidemiological studies examining the effect of age and experience on the overuse injuries that professional dancers sustain. In this study, we hypothesized that younger and less experienced dancers in technical disciplines would sustain more frequent overuse injuries than older and more experienced performers. We also hypothesized that older dancers would accumulate more overuse injuries in the more athletic forms of dance. The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence of overuse injuries in professional ballet as a function of age and/or years of professional practice.

Methods

Research Type, Population, Data Sources

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study performed between January 1, 2005, and October 10, 2010. Included in the study were dancers who were members of leading Spanish ballet companies who sustained injuries and who were diagnosed and treated at Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery Service at Fremap in Madrid. Other inclusion criteria included coverage by an occupational disease and injury insurance policy issued by Fremap and being a dancer in at least one of the following disciplines: classical, neoclassical, contemporary, or Spanish dance.

The data for the study were obtained from the Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery Service at Fremap, mutual insurance company number 61, for labor accidents and occupational illnesses in Madrid, to which the dancers’ companies were associated. The diagnosis of an overuse injury was based on history, physical examination, and imaging studies.

Study Variables

Variables were classified into quantitative—age and years of professional practice; and qualitative—sex, company, ballet discipline practiced when the injury was sustained, etiology of the injury, injury site, affected tissue, and clinical diagnosis.

As the study of the injury was the dependent variable in this study, and taking into account that there were dancers who presented with several injuries, the values of the different parameters analyzed were obtained on the basis of the injuries recorded rather than the number of dancers studied.

Distribution of the Sample Into Groups

In order to assess the influence of age and/or years of professional practice on the occurrence of injuries, we divided the subjects into 3 age groups as follows:

Professional dancers aged 21 years or younger with little professional experience (mean years of professional experience: 2.5 years), referred to as junior professional dancers for the purposes of this study.

Professional dancers aged between 22 and 31 years with more experience (mean years of professional experience: 7.83 years) than the previous group, referred to as intermediate professional dancers for the purposes of this study.

Professional dancers aged 32 years or older with longer experience and more years of professional practice than the rest (mean years of professional experience: 16.19 years), referred to as senior professional dancers for the purposes of this study.

Considering that the population in these 3 groups underwent certain variations during the study period, the values of the different parameters were obtained on the basis of the number of injuries recorded rather than the number of dancers studied.

Statistical Analysis

Homogeneity or independence of qualitative variables was determined by means of the Pearson χ2 test and Fisher exact test. The linear relationship between 2 quantitative variables was determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient, whereas the nonlinear relationship was calculated by means of the Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

The comparison of means between 2 independent groups was carried out using either a Student t test or Welch t test, depending on the homogeneity or heterogeneity of variances (as determined by the Levene test) and by the Mann-Whitney U test if the data did not follow a normal distribution or when the samples were small.

When testing the different hypotheses, the null hypothesis was rejected if the associated P value was less than .05. If this was the case, it was considered that findings reached conventional statistical significance, ruling out the possibility that the differences observed might be due to pure coincidence.

Qualitative variables were characterized using frequency distributions and percentages. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. We used an Excel database (Microsoft Inc) to process the data in the study. The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp).

Results

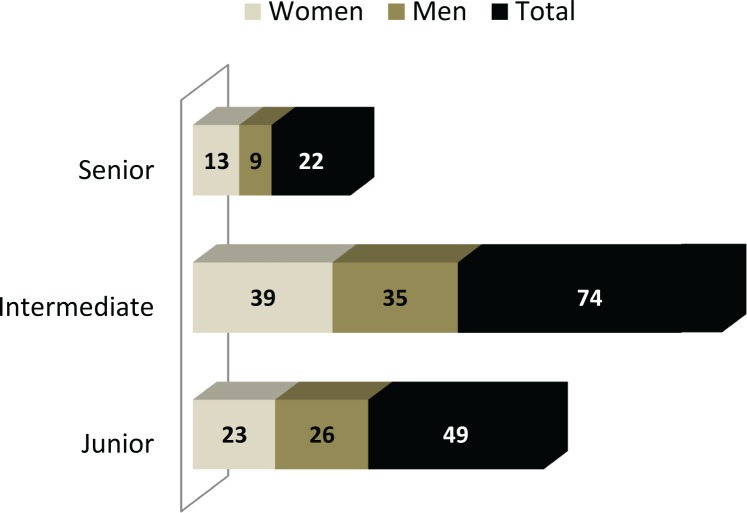

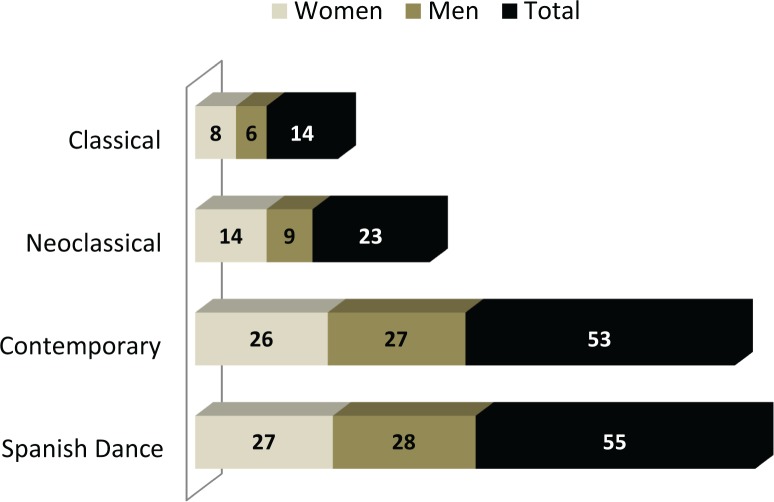

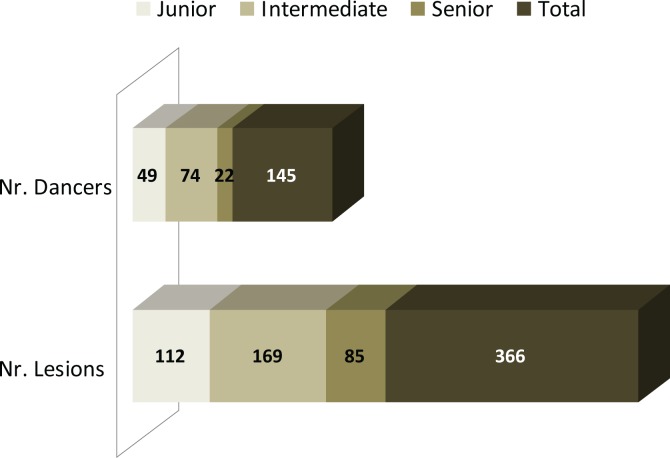

Table 1 shows the injury types of the study sample. Figure 1 shows the distribution of dancers by sex and age. Figure 2 shows the number of male and female dancers in each discipline. More than 75% of the injuries sustained by the dancers were the result of overuse. The prevalence of overuse injuries was 0.239 injuries per 1000 hours of dance.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of Injuries as a Function of Etiology

| Type of Injury | No. of Injuries | % |

|---|---|---|

| Traumatic injury, acute | 118 | 24.3 |

| Nontraumatic injury, overuse | 366 | 75.3 |

| Rheumatic injury | 1 | 0.2 |

| Infectious injury | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 486 | 100.0 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of study participants according to sex and age. Junior, aged ≤21 y; intermediate, aged 22–31 y; senior, aged ≥32 y.

Figure 2.

Distribution of study participants according to sex and discipline.

The prevalence of overuse injuries was analyzed for each of our age groups (Figures 1 and 3). As expected, there was a strong correlation between age and years of professional practice (Table 2). Overuse injuries were more common among the younger dancers, especially women. In men, the prevalence of overuse injuries was similar between junior and senior professional dancers. There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of overuse injuries based on either age or sex (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of study participants and overuse injuries by age group.

TABLE 2.

Mean Values for Age and Years of Professional Practice in the Different Age Groupsa

| Variable | Mean | SD (σ) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Junior professionals | 19.83 | 1.105 | |

| Intermediate professionals | 25.54 | 2.385 | <.001 |

| Senior professionals | 33.66 | 4.131 | |

| Years of professional practice | |||

| Junior professionals | 2.50 | 1.186 | |

| Intermediate professionals | 7.83 | 2.623 | <.001 |

| Senior professionals | 16.19 | 4.648 |

aJunior, aged ≤21 y; intermediate, aged 22–31 y; senior, aged ≥32 y.

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of Overuse Injuries as a Function of Etiology and Age Group

| Junior Professionals | Intermediate Professionals | Senior Professionals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Total | |

| Overuse injuries | |||||||

| n | 61 | 51 | 81 | 88 | 53 | 32 | 366 |

| % | 79.20 | 76.10 | 76.40 | 73.30 | 71.60 | 76.20 | 75.30 |

| Traumatic and other injuries | |||||||

| n | 16 | 16 | 25 | 32 | 21 | 10 | 120 |

| % | 20.80 | 23.90 | 23.60 | 26.70 | 28.40 | 23.80 | 24.70 |

| Total | |||||||

| n | 77 | 67 | 106 | 120 | 74 | 42 | 486 |

| % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| P value | .849 | .740 | .790 | ||||

However, the prevalence of injury was significantly higher (P = .01, χ2 test) among junior professionals who practiced classical ballet, senior dancers who practiced contemporary ballet and intermediate dancers who practiced neoclassical ballet, as compared with other disciplines by age group (Table 4). Certain injuries (patellofemoral syndrome, os trigonum syndrome, second-metatarsal stress fracture, and snapping hip) were seen more frequently in junior professional dancers (P < .05) (Tables 5 and 6).

TABLE 4.

Distribution of Overuse Injuries Into Different Disciplines and Age Groups

| Discipline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Classical | Contemporary | Spanish | Neoclassical | Total |

| Junior professionals | |||||

| n | 32 | 29 | 41 | 10 | 112 |

| % | 42.10 | 26.60 | 33.90 | 16.70 | 30.60 |

| P value | .01 | .346 | .421 | .782 | |

| Intermediate professionals | |||||

| n | 32 | 46 | 55 | 36 | 169 |

| % | 42.10 | 42.20 | 45.50 | 60.00 | 46.20 |

| P value | .146 | .783 | .225 | .01 | |

| Senior professionals | |||||

| n | 12 | 34 | 25 | 14 | 85 |

| % | 15.80 | 31.20 | 20.70 | 23.30 | 23.20 |

| P value | .547 | .01 | .148 | .157 | |

| Total | |||||

| n | 76 | 109 | 121 | 60 | 366 |

| % | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

TABLE 5.

Prevalence of Injuries by Clinical Entity Across the Different Age Groups

| Clinical Entity | Age Group | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Junior Professionals | Intermediate Professionals | Senior Professionals | ||

| Patellofemoral syndrome | ||||

| n | 14 (5 ♀ 9 ♂) | 11 (5 ♀ 6 ♂) | 5 (1 ♀ 4 ♂) | 30 (11 ♀ 19 ♂) |

| % | 12.50 | 6.50 | 5.90 | 8.20 |

| Achilles tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 8 (5 ♀ 3 ♂) | 11 (6 ♀ 5 ♂) | 6 (4 ♀ 2 ♂) | 25 (15 ♀ 10 ♂) |

| % | 7.10 | 6.50 | 7.10 | 6.80 |

| Patellar tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) | 8 (6 ♀ 2 ♂) | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) | 19 (10 ♀ 9 ♂) |

| % | 6.25 | 4.70 | 4.70 | 5.20 |

| Mechanical lower back pain | ||||

| n | 4 (3 ♀ 1 ♂) | 10 (5 ♀ 5 ♂) | 5 (0 ♀ 5 ♂) | 19 (8 ♀ 11 ♂) |

| % | 3.57 | 5.90 | 5.90 | 5.20 |

| Mechanical overload metatarsophalangeal joint of first toe | ||||

| n | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 9 (8 ♀ 1 ♂) | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) | 16 (12 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 2.68 | 5.30 | 4.70 | 4.40 |

| Adductor muscle injury | ||||

| n | 5 (2 ♀ 3 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 15 (7 ♀ 8 ♂) |

| % | 4.45 | 4.10 | 3.50 | 4.10 |

| Lumbar muscle injury | ||||

| n | 4 (3 ♀ 1 ♂) | 5 (2 ♀ 3 ♂) | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) | 13 (6 ♀ 7 ♂) |

| % | 3.60 | 3.00 | 4.70 | 3.55 |

| Peroneal tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 12 (4 ♀ 8 ♂) |

| % | 1.78 | 4.10 | 3.50 | 3.30 |

| Os trigonum syndrome | ||||

| n | 8 (6 ♀ 2 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 11 (8 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 7.10 | 1.77 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Chondral injury of the knee | ||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (3 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) | 11 (7 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 1.77 | 8.25 | 3.00 |

| Flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 5 (3 ♀ 2 ♂) | 5 (2 ♀ 3 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 10 (5 ♀ 5 ♂) |

| % | 4.45 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 2.70 |

| Lumbar disc disease | ||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) | 5 (4 ♀ 1 ♂) | 10 (7 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 2.36 | 5.90 | 2.70 |

| Lateral snapping hip | ||||

| n | 4 (0 ♀ 4 ♂) | 5 (3 ♀ 2 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 10 (3 ♀ 7 ♂) |

| % | 3.60 | 3.00 | 1.20 | 2.70 |

| Cervical muscle injury | ||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 6 (1 ♀ 5 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 9 (1 ♀ 8 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 3.58 | 2.36 | 2.50 |

| Gastrocnemius muscle injury | ||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 6 (3 ♀ 3 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 9 (4 ♀ 5 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 3.56 | 2.36 | 2.50 |

| Iliopsoas tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 8 (2 ♀ 6 ♂) |

| % | 2.68 | 1.18 | 3.50 | 2.20 |

| Plantar fasciitis | ||||

| n | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 5 (3 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 8 (5 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 2.68 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 2.20 |

| Dorsal muscle injury | ||||

| n | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 8 (4 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 3.60 | 1.77 | 1.20 | 2.20 |

| Adductor tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 7 (4 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 2.68 | 0.60 | 3.50 | 1.90 |

| Stress fracture of the second metatarsal | ||||

| n | 5 (0 ♀ 5 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (0 ♀ 7 ♂) |

| % | 4.45 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 1.90 |

| Metatarsalgia | ||||

| n | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (5 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 2.68 | 1.77 | 1.20 | 1.90 |

| Anterior hip pain | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 5 (1 ♀ 4 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 7 (1 ♀ 6 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 3.00 | 2.36 | 1.90 |

| Chronic ankle sprain/synovitis | ||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 1.77 | 3.50 | 1.90 |

| Cervical disc disease | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (4 ♀ 3 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (4 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 4.10 | 0.00 | 1.90 |

| Lumbar facet syndrome | ||||

| n | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 1.78 | 1.77 | 2.36 | 1.90 |

| Mechanical overload of the interphalangeal joint of great toe | ||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 5 (1 ♀ 4 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 6 (2 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 1.64 |

| Mechanical overload of Lisfranc joint | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 5 (0 ♀ 5 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.77 | 2.36 | 1.40 |

| Anterior snapping hip | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 5 (1 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.18 | 3.50 | 1.40 |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (3 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (4 ♀ 0 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 1.77 | 0.00 | 1.10 |

| Quadriceps muscle injury | ||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 1.18 | 1.20 | 1.10 |

| Sesamoiditis of the great toe | ||||

| n | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (0 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 1.78 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 1.10 |

| Hip synovitis | ||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 0.60 | 2.35 | 1.10 |

| Subacromial syndrome | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (3 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 4 (3 ♀ 1 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.77 | 1.20 | 1.10 |

| Hamstring injury | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.18 | 1.20 | 0.80 |

| Shin splints | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.77 | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| Tibialis anterior tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

| Tibialis posterior tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

| Tibial stress fracture | ||||

| n | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 1.78 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

| Other | ||||

| n | 11 (3 ♀ 8 ♂) | 6 (5 ♀ 1 ♂) | 9 (7 ♀ 2 ♂) | 26 (15 ♀ 11 ♂) |

| % | 9.80 | 3.55 | 10.50 | 7.10 |

| Total | ||||

| n | 112 (51 ♀ 61 ♂) | 169 (88 ♀ 81 ♂) | 85 (32 ♀ 53 ♂) | 366 (171 ♀ 195 ♂) |

| % | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

TABLE 6.

Distribution of Significant Prevalence Across Age Groups and Different Clinical Diagnoses

| Age Group | Total | P Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Diagnosis | Junior Professionals | Intermediate Professionals | Senior Professionals | ||

| Patellofemoral syndrome | |||||

| n | 14 | 11 | 5 | 30 | .04 |

| % | 12.50 | 6.50 | 5.90 | 8.20 | |

| Os trigonum syndrome | |||||

| n | 8 | 3 | 0 | 11 | .004 |

| % | 7.10 | 1.77 | 0.00 | 3.00 | |

| Stress fracture of the second metatarsal | |||||

| n | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 | .03 |

| % | 4.45 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 1.90 | |

| Lateral snapping hip | |||||

| n | 4 | 5 | 1 | 10 | .143 |

| % | 3.00 | 3.60 | 1.20 | 2.70 | |

| Achilles tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 8 | 11 | 6 | 25 | .742 |

| % | 7.10 | 6.50 | 7.10 | 6.80 | |

| Patellar tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 7 | 8 | 4 | 19 | .635 |

| % | 6.25 | 4.70 | 5.00 | 5.20 | |

| Chondropathy of the knee | |||||

| n | 1 | 3 | 7 | 11 | .004 |

| % | 0.90 | 1.77 | 8.00 | 3.00 | |

| Lumbar disc disease | |||||

| n | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | .117 |

| % | 0.90 | 2.36 | 6.00 | 2.70 | |

| Cervical muscle injury | |||||

| n | 1 | 6 | 2 | 9 | .004 |

| % | 0.90 | 3.58 | 2.00 | 2.50 | |

| Cervical disc disease | |||||

| n | 4 | 5 | 1 | 10 | .033 |

| % | 3.60 | 3.00 | 1.20 | 2.70 | |

aBoldfaced P values indicate statistical significance (P < .05).

Achilles tendinopathy was one of the conditions showing a similar prevalence across the different groups. Other conditions such as chondral injury of the knee or lumbar disc disease became more prevalent with increasing age and years of professional practice, with chondral injury of the knee being statistically more common (P = .004, χ2 test) among senior dancers with respect to the other 2 age groups. Disc disease was significantly more common in intermediate dancers (P = .004) (Table 6).

Sex-based differences were seen for some injuries. Second-metatarsal stress fracture, mechanical overload of the Lisfranc joint, hip joint injuries, and cervical muscle overuse injuries were statistically more common in females. Conversely, overload of the first metatarsophalangeal joint and rotator cuff tendinopathy were more commonly seen in men (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Distribution of Significant Prevalence Across Sex and Different Clinical Diagnoses

| Men | Women | Total | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress fracture of the second metatarsal | ||||

| n | 0 | 7 | 7 | .01 |

| % | 0.00 | 1.90 | 1.90 | |

| Mechanical overload of Lisfranc joint | ||||

| n | 0 | 5 | 5 | .04 |

| % | 0.00 | 1.40 | 1.40 | |

| Cervical muscle injury | ||||

| n | 1 | 8 | 9 | .02 |

| % | 0.30 | 2.20 | 2.50 | |

| Mechanical overload of the first metatarsophalangeal joint | ||||

| n | 12 | 4 | 16 | .01 |

| % | 3.30 | 1.10 | 4.40 | |

| Subacromial syndrome | ||||

| n | 4 | 0 | 4 | .02 |

| % | 1.10 | 0.00 | 1.10 | |

| Rotator cuff tendinopathy | ||||

| n | 4 | 0 | 4 | .02 |

| % | 1.10 | 0.00 | 1.10 | |

| Hip pain injuries | ||||

| n | 13 | 32 | 45 | |

| % | 7.6 | 16.4 | 12.3 | .01 |

| Other injuries | ||||

| n | 158 | 163 | 321 | |

| % | 92.4 | 83.6 | 87.7 |

aBoldfaced P values indicate statistical significance (P < .05).

Regarding anatomic location by age group (Table 8), ankle injuries were more frequent in junior professional dancers, spine ankle and foot in intermediate professional dancers, and spine hip and knee injuries in senior professional dancers.

TABLE 8.

Distribution of Injury Prevalence by Anatomic Location Across the Different Age Groups

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Junior, % (n) | Intermediate, % (n) | Senior, % (n) | Total, % (n) |

| Spine | 15.2 (17) | 23.1 (39) | 22.4 (19) | 20.5 (75) |

| Hip and pelvis | 13.4 (15) | 11.3 (19) | 22.4 (19) | 14.5 (53) |

| Thigh | 5.4 (6) | 6.5 (11) | 5.9 (5) | 6.0 (22) |

| Knee | 21.4 (24) | 13.6 (23) | 22.4 (19) | 18.0 (66) |

| Leg | 2.7 (3) | 5.3 (9) | 2.4 (2) | 3.8 (14) |

| Ankle | 25.0 (28) | 19.5 (33) | 14.1 (12) | 19.9 (73) |

| Foot | 16.1 (18) | 17.2 (29) | 8.2 (7) | 14.8 (54) |

| Shoulder | 0.9 (1) | 3.6 (6) | 1.1 (1) | 2.2 (8) |

| Upper limbs | 1.1 (1) | 0.3 (1) | ||

| Total | 100.0 (112) | 100.0 (169) | 100.0 (85) | 100.0 (366) |

Discussion

The literature on ballet-related injuries is rather heterogeneous. Many studies do not provide specific diagnoses and either draw their conclusions from questionnaires or fail to contain a methodological description of the data collection process employed.12 Other studies,3,7,11,17,20,25,32 including the present one, rely on clinical history and physical examination to make a specific diagnosis.

We based our calculations on the number of injuries sustained rather on the number of dancers injured. It was common for dancers to experience more than 1 overuse injury during the time period of this study. This methodology has been used by previous studies.3,10,17,21,32

We found that the majority of injuries in dance were overuse injuries. This is in agreement with previous studies on ballet dancers.2,7,12,17,21 However, we are aware of only 1 previous study that looked solely at professional dancers, and the data in that study were categorized by anatomic location rather than by specific diagnosis.5

It is difficult to compare the injury rate in dancers with other professions, as there is no uniform methodology for measuring workplace exposure.11 A previous study on injuries in dancers reported injury rates of 0.18 per 1000 hours in professional and 4.7 per 1000 hours in amateurs.12 Nilsson et al21 reported a rate of 0.6 injuries per 1000 hours of dance for a group of professional dancers with a mean age of 28.3 years. Gamboa et al11 reported an injury rate of 0.77 injuries per 1000 hours of dance in adolescent dancers.

Our injury rate (0.239/1000 dance hours) was less than those previously reported because we did not include minor traumatic injuries, which were frequently seen in the other studies. Our long-standing experience of caring for professional dancers, and the realization that there exist differences between the types of injuries sustained by younger as compared with more senior dancers, prompted us to carry out this study to try to define those differences.

Our literature review did not identify any study that looked at the effect of age or years of training on the injury rates of professional dancers. We did find, however, 1 study on injuries sustained by amateurs that divided the sample into age groups.17 We also found other reports that compared the findings of a series of studies on the injuries sustained by preprofessional dancers with those of studies on the injuries sustained by professionals.6,12

The available studies have conflicting conclusions, with some studies showing an increased rate of injury with more years of training12 and others showing that younger, less experienced dancers have higher injury rates.6,33 Our study also showed that the highest prevalence of overuse injuries was observed in younger dancers, especially females.

Previous studies have shown a clear predisposition for certain injuries in certain age groups. Second-metatarsal stress fractures are more common in skeletally immature dancers,1 and patellofemoral syndrome is also more common among younger dancers.23,26 We also found higher rates of second-metatarsal stress fracture, patellofemoral syndrome, and lateral snapping hip in junior professional dancers, especially in the more technical disciplines. In contrast, chondral injury of the knee and lumbar disc disease were more prevalent in senior dancers and in the more athletic disciplines.

It would therefore seem that while at a younger age it is the more technically demanding disciplines that favor the development of overuse injuries, in the more physically demanding disciplines, which generally allow a greater freedom of movement, most overuse injuries result from a mechanical overload that intensifies with the passage of time (Table 9).32

TABLE 9.

Distribution of Overuse Injuries by Ballet Discipline and Sex

| Overuse Injury | Discipline | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Contemporary | Spanish | Neoclassical | ||

| Patellofemoral syndrome | |||||

| n | 12 (4 ♀ 8 ♂) | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) | 9 (3 ♀ 6 ♂) | 5 (3 ♀ 2 ♂) | 30 (11 ♀ 19 ♂) |

| % | 15.79 | 3.67 | 7.44 | 8.33 | 8.20 |

| Achilles tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 6 (2 ♀ 4 ♂) | 8 (4 ♀ 4 ♂) | 6 (6 ♀ 0 ♂) | 5 (3 ♀ 2 ♂) | 25 (15 ♀ 10 ♂) |

| % | 7.89 | 7.34 | 4.96 | 8.33 | 6.83 |

| Patellar tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 8 (4 ♀ 4 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 6 (2 ♀ 4 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 19 (10 ♀ 9 ♂) |

| % | 10.53 | 2.75 | 4.96 | 3.33 | 5.19 |

| Mechanical low back pain | |||||

| n | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 9 (4 ♀ 5 ♂) | 5 (4 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 19 (8 ♀ 11 ♂) |

| % | 3.95 | 8.26 | 4.13 | 3.33 | 5.19 |

| Mechanical overload MTTF 1° | |||||

| n | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (6 ♀ 1 ♂) | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) | 3 (3 ♀ 0 ♂) | 16 (12 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 6.42 | 3.31 | 5.00 | 4.37 |

| Adductor muscle injury | |||||

| n | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 11 (6 ♀ 5 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 15 (7 ♀ 8 ♂) |

| % | 3.95 | 0.00 | 9.09 | 1.67 | 4.10 |

| Lumbar muscle injury | |||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) | 5 (1 ♀ 4 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 13 (6 ♀ 7 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 3.67 | 4.13 | 5.00 | 3.55 |

| Peroneal tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 6 (1 ♀ 5 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 12 (4 ♀ 8 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 5.50 | 1.65 | 5.00 | 3.28 |

| Os trigonum syndrome | |||||

| n | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 5 (4 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 11 (8 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 4.59 | 1.65 | 3.33 | 3.01 |

| Chondral injury of the knee | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 6 (4 ♀ 2 ♂) | 3 (3 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 11 (7 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 5.50 | 2.48 | 3.33 | 3.01 |

| Flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 3 (3 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 10 (5 ♀ 5 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 2.75 | 1.65 | 5.00 | 2.73 |

| Lumbar disc disease | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 5 (4 ♀ 1 ♂) | 4 (3 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 10 (7 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 4.59 | 3.31 | 0.00 | 2.73 |

| Lateral snapping hip | |||||

| n | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 5 (2 ♀ 3 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 10 (3 ♀ 7 ♂) |

| % | 5.26 | 0.00 | 4.13 | 1.67 | 2.73 |

| Calf muscle injury | |||||

| n | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 9 (4 ♀ 5 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 1.83 | 1.65 | 5.00 | 2.46 |

| Neck muscle injury | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 9 (1 ♀ 8 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 1.83 | 2.48 | 5.00 | 2.46 |

| Iliopsoas tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 8 (2 ♀ 6 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 0.92 | 3.31 | 5.00 | 2.19 |

| Heel pain/plantar fasciitis | |||||

| n | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (3 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 8 (5 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 0.92 | 3.31 | 1.67 | 2.19 |

| Dorsal muscle injury | |||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 6 (2 ♀ 4 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 8 (4 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 0.92 | 4.96 | 0.00 | 2.19 |

| Adductor tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 5 (3 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (4 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 0.00 | 4.13 | 0.00 | 1.91 |

| Low back facet syndrome | |||||

| n | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 5 (3 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 0.00 | 4.13 | 0.00 | 1.91 |

| Metatarsalgia | |||||

| n | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (5 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 2.75 | 1.65 | 1.67 | 1.91 |

| Fx stress 2 | |||||

| n | 4 (0 ♀ 4 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 7 (0 ♀ 7 ♂) |

| % | 5.26 | 2.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.91 |

| Chronic sprain/ankle sinovitis | |||||

| n | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 3.95 | 1.83 | 0.83 | 1.67 | 1.91 |

| Cervical disc disease | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 7 (4 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.83 | 3.31 | 1.67 | 1.91 |

| Anterior hip pain | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 7 (1 ♀ 6 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 2.75 | 1.65 | 1.67 | 1.91 |

| Interphalangical mechanical overload (IF) first toe | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 6 (2 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 1.83 | 0.83 | 3.33 | 1.64 |

| Mechanical overload Lisfranc joint | |||||

| n | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 3 (0 ♀ 3 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 5 (0 ♀ 5 ♂) |

| % | 2.63 | 2.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.37 |

| Anterior snapping hip | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 5 (1 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 2.75 | 0.83 | 1.67 | 1.37 |

| Shoulder rotator cuff tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (4 ♀ 0 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.83 | 1.65 | 0.00 | 1.09 |

| Hip sinovitis | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 4 (1 ♀ 3 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 1.83 | 0.00 | 1.67 | 1.09 |

| Sesamoiditis first toe | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (0 ♀ 4 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 1.83 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 1.09 |

| Subachromial syndrome | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (3 ♀ 1 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 1.83 | 0.00 | 3.33 | 1.09 |

| Quadriceps muscle injury | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 0.00 | 1.65 | 1.67 | 1.09 |

| Shin splints/tibial periostitis | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (2 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 3 (2 ♀ 1 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.65 | 1.67 | 0.82 |

| Hamstring muscle injury | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 3 (1 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 0.92 | 1.65 | 0.00 | 0.82 |

| Posterior tibial tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (1 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (1 ♀ 1 ♂) |

| % | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.55 |

| Anterior tibial tendinopathy | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.67 | 0.55 |

| Tibial stress fracture | |||||

| n | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 1 (0 ♀ 1 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 0 (0 ♀ 0 ♂) | 2 (0 ♀ 2 ♂) |

| % | 1.32 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.55 |

| Other | |||||

| n | 4 (2 ♀ 2 ♂) | 10 (9 ♀ 1 ♂) | 7 (3 ♀ 4 ♂) | 5 (1 ♀ 4 ♂) | 26 (15 ♀ 11 ♂) |

| % | 5.26 | 9.17 | 5.78 | 8.33 | 7.10 |

| Total | |||||

| n | 76 (25 ♀ 51 ♂) | 109 (60 ♀ 49 ♂) | 121 (62 ♀ 59 ♂) | 60 (24 ♀ 36 ♂) | 366 (171 ♀ 195 ♂) |

| % | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

aFx stress 2, stress fracture of the base of the second metatarsal; MTTF 1°, first metatarsophalangeal joint.

Also, the overuse injuries resulting from pathomechanic alteration were more common in women, who are usually subject to greater technical demands than men. Similarly, the injuries related to more physical demands were more common among men, who are usually subject to more athletic requirements. For example, second-metatarsal stress fractures are related to the use of pointe shoes in women, whereas rotator cuff pathology is connected to the performance of portées by men.

Limitations of this study include that it was carried out between the professional dancers of different ballet companies. Although these were the main companies in Spain, they practiced different ballet disciplines. There is a potential bias toward more proficient technical dancers in our older population. It is possible that younger dancers with bad mechanics have been “weeded out” because of poor technical performance.

We believe that the higher injury rates in junior professional dancers may be related to the need for less technically accomplished dancers to perform more repetitions of each movement in practice in order to achieve their performance goals. The findings of this study could provide guidance to ballet schools in terms of the need to develop a series of preventive measures to minimize the occurrence of injuries in ballet dancers.31 Nonetheless, these findings should be corroborated by further rigorous study.

Conclusion

The findings of this study were that overuse injuries were significantly the most prevalent among the professional dancers under study, especially among younger and younger female professionals practicing the more technical disciplines. Second, the most prevalent conditions in the more technical disciplines, such as classical ballet, were also the most common among younger dancers, with a tendency to decrease with increasing age. On the other hand, the most prevalent conditions in the more athletic disciplines, such as contemporary ballet, were also the most frequent among veteran professionals. Finally, we found that the most prevalent pathology among junior professional dancers was patellofemoral syndrome, especially in women, whereas Achilles tendinopathy was the most prevalent condition among dancers in the intermediate group. The highest prevalence of chondral injury of the knee was found among senior dancers.

Footnotes

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Fremap Hospital System, Madrid, Spain.

References

- 1. Albisetti W, Perugia D, De Bartolomeo O, Tagliabue L, Camerucci E, Calori GM. Stress fractures of the base of the metatarsal bones in young trainee ballet dancers. Int Orthop. 2010;34:51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allen N, Nevill A, Brooks J, Kouledakis Y, Wyon M. Ballet injuries: injury incidence and severity over 1 year. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arendt Y, Kerschbaumer F. Injury and overuse pattern in professional ballet dancers. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2003;141:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ballius R, Ballius X. Contribución de la biomecánica en la interpretación patogénica y en la prevención de las injuries deportivas de sobrecarga. Avances Traumatol Cirugía Rehabil Med Prev Deporte. 1986;16:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowling A. Injuries to dance: prevalence, treatment and perceptions of causes. BMJ. 1989;298:731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bronner S, Ojofeitimi S, Rose D. Injuries in a modern dance company: effect of comprehensive management of injury incidence and time loss. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Byhring S, Bo K. Musculoskeletal injuries in the Norwegian Nacional Ballet: a prospective cohort study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002;12:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cichanowski H, Schmitt J, Johnson R, Niemuth P. Hip strength in collegiate female athletes with patellofemoral pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Echegoyen S, Acuña E, Rodriguez C. Injuries in students of three different dance techniques. Med Probl Perform Artist. 2010;25:72–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frusztajer NT, Dhuper S, Warren MP, Brooks-Gunn J, Fox RP. Nutrition and the incidence of stress fractures in ballet dancers. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:779–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gamboa J, Roberts L, Maring J, Fergus A. Injury patterns in elite preprofessional ballet dancers and the utility of screening programs to identify risk characteristics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;28:126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hincapie C, Morton E, Cassidy J. Musculoskeletal injuries and pain in dancers: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1819–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kadel NJ. Foot and ankle injuries in dance. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17:813–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kadel NJ, Teitz CC, Kronmal RA. Stress fractures in ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khan K, Brown J, Way S, et al. Overuse injuries in classical ballet. Sports Med. 1995;19:341–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koutedakis Y, Jamurtas A. The dancer as a performing athlete: physiological considerations. Sports Med. 2004;34:651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leandersson C, Leanderson J, Wykman A, Strender LE, Johansson SE, Sundquist K. Musculoskeletal injuries in young ballet dancers. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1531–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lozano S, Vargas A. El en-dehors en la danza clásica: mecanismos de producción de lisiones. Rev Centro Investig Flamenco Telethusa. 2010;3(3):4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Milan KR. Injury in ballet: a review of relevant topics for the physical therapist. J Orthop Sports PhysTher. 1994;19:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Negus V, Hopper D, Briffa N. Associations between turnout and lower extremity injuries in classical ballet dancers. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nilsson C, Leanderson J, Wykmann A, Strendler L. The injury panorama in a Swedish professional ballet company. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramiro A, Loring T, Pérez JC, Henares J. Lesiones deportivas de esfuerzo. Nuestro concepto y clasificación patogénica In: Lesiones deportivas. Libro del XXII Simposium Internacional de Traumatología Ortopedia FREMAP. Madrid, Spain: Fundación Mapfre Medicina; 1996:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reid D. Prevention of hip and knee injuries in ballet dancers. Sports Med. 1988;6:295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reid D, Burnham RS, Saboe L, Kushner S. Lower extremity flexibility patterns in classical Ballet dancers and their correlation to lateral hip and knee injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodriguez D, Sanz I. Incidencia de lesiones en el pie del bailarín. Rev Int Ciencias Podol. 2008;2(2):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rovere G, Webb L, Gristina A, Vogel J. Musculoskeletal injuries in theatrical dance students. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11:195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shan G. Comparison of repetitive movements between ballet dancers and martial artists: risk assessment of muscle overuse injuries and prevention strategies. Res Sports Med. 2005;13:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slocum DB, James SL. Biomechanics of running. JAMA. 1968;205:721–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sobrino FJ, Guillén P. Lesiones en el ballet. Estudio epidemiológico In: Lesiones deportivas. Libro del XXII Simposium Internacional de Traumatología Ortopedia FREMAP. Madrid, Spain: Fundación Mapfre Medicina; 1996:73–120. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sobrino FJ. Patología Crónica Acumulativa por Microtraumatismos de Repetición: nueva definición, patogenia, clínica general, factores de riesgo, controversias. Mapfre Med. 2003;14:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sobrino FJ. Lesiones acumulativas por microtraumatismos de repetición en el ballet [doctoral thesis] Madrid, Spain: Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 2013. http://eprints.ucm.es/24622/1/T35240.pdf. Accessed December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sobrino FJ, de la Cuadra C, Guillén P. Overuse injuries in professional ballet. Injury-based differences among ballet disciplines. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3:2325967115590114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Solomon R, Micheli L, Solomon J, Kelly T. The cost of injuries in a professional ballet company. Anatomy of season. Med Probl Perform Artist. 1995;10:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walls R, Brennan S, Hodnett P. Overuse ankle injuries in professional Irish dancers. Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;16:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]