Abstract

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to describe the experiences and challenges of supporting family caregivers of seniors with complex needs and to outline support strategies and research priorities aimed at supporting them.

Design and Methods

A CIHR-funded, two-day conference entitled “Supporting Family Caregivers of Seniors: Improving Care and Caregiver Outcomes” was held. An integrated knowledge translation approach guided this planning conference. Day 1 included presentations of research evidence, followed by participant engagement Qualitative data was collected regarding facilitators, barriers/gaps, and recommendations for the provision of caregiver supports. Day 2 focused on determination of research priorities.

Results

Identified facilitators to the provision of caregiver support included accessibility of health-care and community-based resources, availability of well-intended health-care providers, and recognition of caregivers by the system. Barriers/gaps related to challenges with communication, access to information, knowledge of what is needed, system navigation, access to financial resources, and current policies. Recommendations regarding caregiver services and research revolved around assisting caregivers to self-identify and seek support, formalizing caregiver supports, centralizing resources, making system navigation available, and preparing the next generation for caregiving.

Implication

A better understanding of the needs of family caregivers and ways to support them is critical to seniors’ health services redesign.

Keywords: caregivers, seniors, comorbidities

INTRODUCTION

Canada’s population is aging, with the proportion of individuals aged 65 and over anticipated to increase from 15.3% in 2013 up to 27.8% in 2063, and those aged 80 and over to increase from 1.4 million to 4.9 million between 2013 and 2045 (10% of the total Canadian population).(1) Simultaneously, more Canadians are living with chronic diseases, including dementia, with a third of those aged 80 years and older having at least four chronic conditions.(2) In 2011, 14.9% of Canadians aged 65 and older were living with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias; this figure may double by 2031.(3)

Family members and friends are often relied upon to help them continue to live and remain in their communities.(4) Family caregivers provide informal unpaid care.(5) Recognized as the backbone of the health care system,(2,6,7) it is estimated that 3.8 million family caregivers care for seniors with short- or long-term health conditions,(8) and nearly half a million care for someone with dementia.(4) Caregivers of individuals with dementia are often older, likely to be caring for parents (in-laws), and living within commuting distance (< 3 hours by car).(4) According to a 2012 Statistics Canada survey,(6) of the 8.1 million Canadians identified as carers (44% of whom are aged 45–64 years), 10% provide more than 30 hours of support a week, many are working (60%), and others are caregiving while child-rearing (25%).(6)

Family caregivers are increasingly overburdened,(2,6,7) with 50% reportedly being tired and anxious, and 20% in need of financial assistance.(6) Those providing greater than 21 hours of care per week, or caring for persons with depression, cognitive decline, behavioural change, or terminal conditions, are at higher risk.(7,9) There is increasing evidence that caregiving is being provided at significant physical, emotional, and financial cost to caregivers(2,6,7,10) who are often overwhelmed by the stresses of caregiving and competing priorities. Family caregivers can experience deterioration of their health, social isolation, loss of income, family conflict, and distress.(7,11,12) Compared to other caregivers, those caring for someone with dementia (generally spending 14 hours/week caregiving) are more greatly impacted regarding their health, social, and financial well-being,(4) with up to 75% developing psychological illnesses and 15–32% experiencing depression.(5) This strain is anticipated to intensify due to an aging population.(4,13,14)

A recent Canadian study estimates the costs of unpaid caregiving at $25 billion.(10) Given the essential role of caregivers within the health-care system, supporting family caregivers has become a national public health priority. Multiple reports, including the Health Council of Canada’s (2012) Seniors In Needs, Caregivers In Distress report, identify the need to support caregivers and recognize their indispensable contribution in the sustainability of the health-care system. (2,6,7,10) The provision of adequate evidence-informed family caregiver supports should be an important part of any regional, provincial, national, or international strategy for the care of older adults or those with dementia.(15) Caregivers require multi-faceted support to foster resilience and ensure that they can continue to provide care while maintaining their own well-being. There is, however, a gap between available and known supports to help caregivers. A better understanding of caregiver expectations and ways to foster their resilience is needed.

To that end, a CIHR-funded, two-day conference entitled “Supporting Family Caregivers of Seniors: Improving Care and Caregiver Outcomes” was convened to bring together individuals from various organizations and sectors. The anticipated outcomes included gaining a greater understanding of the current state of support for family caregivers, identifying what is needed provincially, nationally, and internationally to improve service provision and caregiver support, and informing research priorities. The focus of this paper is specific to caregiver support for seniors with complex needs— that is older adults with chronic conditions and how they interact with each other and the processes of aging through biomedical, psychological, and social mechanisms.(16)

METHODS

The purpose of this paper is to: 1) describe the experiences and challenges of supporting family caregivers of seniors with complex health needs from the perspective of participants, and 2) outline research priorities aimed at supporting these family caregivers. The planning meeting employed an integrated knowledge translation approach guided by the knowledge-to-action cycle.(17) Modified World Café(18) and stakeholder engagement were used to gather participant insights and feedback.

Participants

Participants were invited via email by key stakeholders from organizations and groups, such as Covenant Health, Alberta Health Services, Government of Alberta, international universities, Alberta Caregivers Association, and the Alzheimer’s Society. The conference was attended by 120 stakeholders, including caregivers, researchers, health-care providers, members of community organizations, government officials, and policy and decision makers in Edmonton, Alberta on April 14–15, 2014. Representatives from a number of key national institutions attended, along with international research experts and stakeholders (e.g., World Health Organization, Stanford University). Participants engaged in interactive discussions concerning complex needs (n = 76; hereafter ‘target group’) on Day 1, and implementation strategies and research priorities to address gaps and barriers on Day 2. This group was comprised of 9 caregivers, as well as 59 health-care workers, 5 participants from provincial bodies, and 3 from community organizations, some of whom also identified as caregivers. Two of the participants were from outside of Alberta. The groups were intentionally comprised of participants holding diverse perspectives (caregivers, health-care providers, policy and decision makers, and community organizations) so that ideas shared might co-mingle, and inform and build upon each other, thereby enabling the group to co-produce knowledge. As a result, identification of the source of a particular concept or statement was not emphasized.

Data Collection

The conference utilized an integrated knowledge translation approach that was in keeping with the evidence-funnel within the knowledge-to-action cycle.(17) Data were collected from conference participants on each day of the conference. Day 1 began with summary presentations of research evidence specific to support for caregivers of seniors in the three target populations (caregivers of seniors with dementia, end-of-life care, or complex health needs). A modified World Café technique(18) of 90-minute duration was then utilized to elicit experiences and gather informative data from participants. This involved dividing participants (n = 120) into three groups aligned with each of the target populations. Participants self-identified and registered for each group. The complex needs (n = 76) group was further subdivided into groups of 10–12 people who rotated over a 60-minute period through three topic-specific table discussions focused on current issues related to challenges, barriers, resources, facilitators, and desired directions to the provision of caregiver supports. Each of the table discussions was facilitated by an experienced moderator accompanied by a scribe. Participants also penned ideas on post-it-notes, cue cards, or table coverings, leaving them behind for the next group to build upon. After 60 minutes, table moderators provided a 30-minute summation of the collective discussion from the three discussion rounds for each target population. All participants then reconvened and World Café results from each of the three target groups were shared over an hour-long session.

On Day 2, participants were divided into the three target population groups who engaged in 6 hours of discussion regarding research priorities. Again, 76 participants discussed support for caregivers of seniors with complex needs. All participants reconvened for a 1-hour discussion regarding research priorities across the each target populations. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board.

Data Analysis

Notes from the scribes, together with those on post-it-notes, cue cards, and table coverings, were collated for the purpose of analysis and writing of a final report for the funding agency. Qualitative data analysis was conducted by four members of the research team (MJ, SBP, JP, LC), using inductive content analysis guided by qualitative description.(19,20) NVivo 9 software(21) was utilized to support analysis of the qualitative data obtained over the two days. Themes were developed based on keywords; subthemes offered more clarification. To ensure the integrity of the research process, four aspects of trustworthiness—credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability, detailed in Lincoln and Guba’s model(22)— were addressed throughout the analysis processes. As data were collected in the context of an intentionally heterogenous group of caregivers and system representatives holding diverse perspectives and at times dual roles, participant responses were analyzed as a single unit of analysis representative of their co-produced knowledge. This unit of analysis did not differentiate the approaches or findings presented by specific participants or participant subgroups.

RESULTS

Group discussions on Day 1 highlighted caregiver experiences, and facilitators and barriers/gaps to support for caregivers. Emphasis was placed on the following caregiver experiences: 1) managing a multitude of tasks which can compromise caregivers’ ability to address personal needs, 2) changing roles and obligations, and the shift away from traditional family structures which is having an impact on caregiving, and 3) the significant financial and occupational impact of caregiving (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Supporting family caregivers of seniors with complex needs: caregiver experiences

| Themes | Findings |

|---|---|

| 1. Caregiving involves managing a multitude of tasks, which can compromise caregivers’ ability to address personal needs | Caregiving often includes managing household tasks, yard work, groceries, driving, and transportation, and leaves little time to attend to their personal needs. This can lead to burnout and isolation. “Demands on caregivers of those with complex needs are high. They need relief, time off, self care.” Caregivers, who tend to not self-identify, often have multiple demands which are constantly in flux (e.g., employment). This can lead to lack of timely access to resources. As the demands mount, the scope of their life narrows on the needs of the care recipient. “…desperation, exhaustion, total mental, physical, everything, like I just can’t do this anymore but I have to - there’s nobody else.” |

| 2. Changing roles and obligations, and the shift away from traditional family structures is having an impact on caregiving | Caregivers experience a shift in roles and obligations due to changes in the abilities and needs of the care partner(s). This affects relationships with and between partners, spouses, siblings, and friends. The shift away from the traditional family unit due to factors such as immigration, inter-racial, same-sex marriage, divorce, and a highly mobile population also impacts caregiving. Significant inter-generational and cultural issues can arise, and family dynamics, expectations, and language barriers can further complicate matters related to caregiving. “Family dynamics: immigration to Canada, older generation not having the same experience caring for their parents/seniors and therefore the expectation is higher for current adult children.” “Loss and grief. My husband and my relationship is not the same as he becomes sicker…you lose companionship and friendship.” Caregiving from a distance was also noted to be a common experience. This places distinct demands on caregivers (e.g., related to time, travel, and communication). In an “instant communication” society, there are higher expectations to respond immediately to concerns placed on adult children. “Long distance caregiving, supporting parents in different parts of the country.” |

| 3. The financial and occupational impact of caregiving is significant | Many caregivers bear the financial burden of costs associated with medical services and supplies, medication, and transportation. They often utilize their own savings to manage costs. Some give up jobs, relocate, or adjust schedules to accommodate. This can have a significant impact on their own livelihood, future employment and financial stability, as well as other benefits that their work life affords them. |

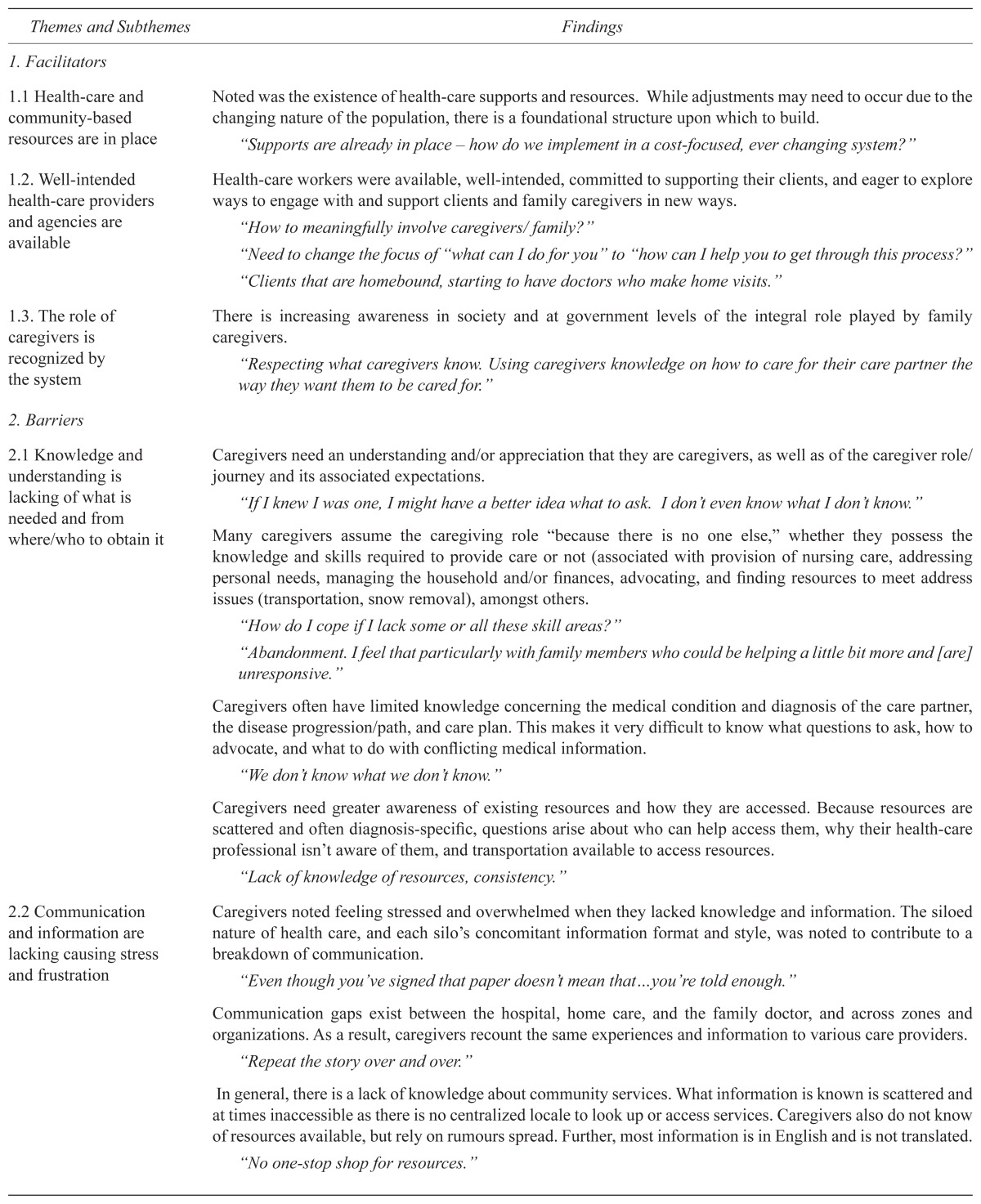

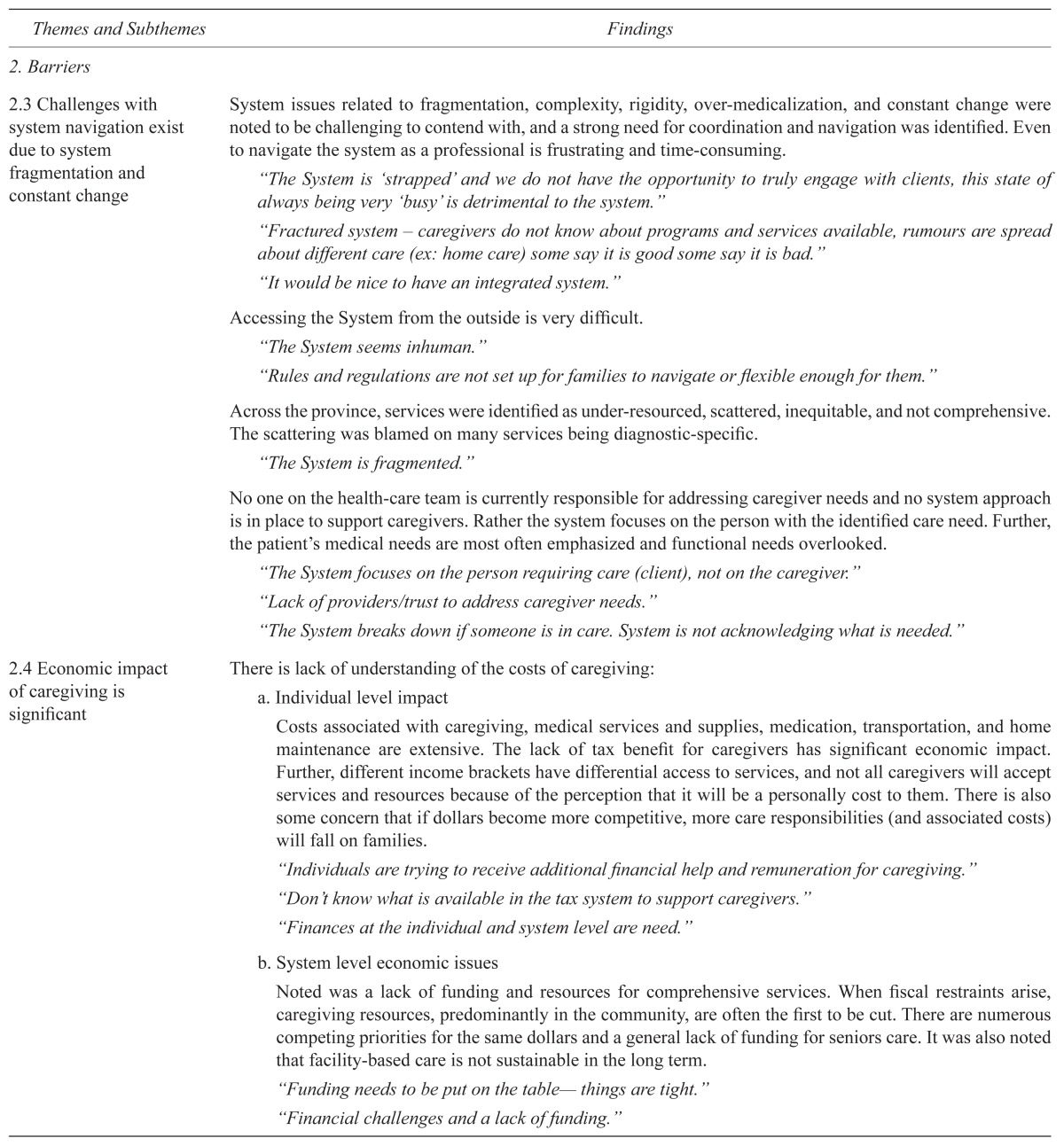

Themes associated with facilitators and barriers/gaps to provision of support for caregivers were also identified (see Table 2). Facilitators included: 1) health-care and community-based resources are accessible, 2) health-care providers and agencies are available and well-intended, and 3) caregivers are recognized by the system. Barriers/gaps included: 1) caregivers lack knowledge and understanding of what is needed and from whom/where to obtain it, 2) communication and information is lacking causing caregivers stress and frustration, 3) challenges with system navigation exist due to fragmentation and constant change, 4) economic barriers exist at the individual and system levels, and 5) policies can create barriers.

TABLE 2.

Supporting family caregivers of seniors with complex needs: facilitators/barriers to the provision of caregiver support

| Themes and Subthemes | Findings |

|---|---|

| 1. Facilitators | |

| 1.1 Health-care and community-based resources are in place | Noted was the existence of health-care supports and resources. While adjustments may need to occur due to the changing nature of the population, there is a foundational structure upon which to build. “Supports are already in place – how do we implement in a cost-focused, ever changing system?” |

| 1.2. Well-intended health-care providers and agencies are available | Health-care workers were available, well-intended, committed to supporting their clients, and eager to explore ways to engage with and support clients and family caregivers in new ways. “How to meaningfully involve caregivers/ family?” “Need to change the focus of “what can I do for you” to “how can I help you to get through this process?” “Clients that are homebound, starting to have doctors who make home visits.” |

| 1.3. The role of caregivers is recognized by the system | There is increasing awareness in society and at government levels of the integral role played by family caregivers. “Respecting what caregivers know. Using caregivers knowledge on how to care for their care partner the way they want them to be cared for.” |

| 2. Barriers | |

| 2.1 Knowledge and understanding is lacking of what is needed and from where/who to obtain it | Caregivers need an understanding and/or appreciation that they are caregivers, as well as of the caregiver role/journey and its associated expectations. “If I knew I was one, I might have a better idea what to ask. I don’t even know what I don’t know.” Many caregivers assume the caregiving role “because there is no one else,” whether they possess the knowledge and skills required to provide care or not (associated with provision of nursing care, addressing personal needs, managing the household and/or finances, advocating, and finding resources to meet address issues (transportation, snow removal), amongst others. “How do I cope if I lack some or all these skill areas?” “Abandonment. I feel that particularly with family members who could be helping a little bit more and [are] unresponsive.” Caregivers often have limited knowledge concerning the medical condition and diagnosis of the care partner, the disease progression/path, and care plan. This makes it very difficult to know what questions to ask, how to advocate, and what to do with conflicting medical information. “We don’t know what we don’t know.” Caregivers need greater awareness of existing resources and how they are accessed. Because resources are scattered and often diagnosis-specific, questions arise about who can help access them, why their health-care professional isn’t aware of them, and transportation available to access resources. “Lack of knowledge of resources, consistency.” |

| 2.2 Communication and information are lacking causing stress and frustration | Caregivers noted feeling stressed and overwhelmed when they lacked knowledge and information. The siloed nature of health care, and each silo’s concomitant information format and style, was noted to contribute to a breakdown of communication. “Even though you’ve signed that paper doesn’t mean that…you’re told enough.” Communication gaps exist between the hospital, home care, and the family doctor, and across zones and organizations. As a result, caregivers recount the same experiences and information to various care providers. “Repeat the story over and over.” In general, there is a lack of knowledge about community services. What information is known is scattered and at times inaccessible as there is no centralized locale to look up or access services. Caregivers also do not know of resources available, but rely on rumours spread. Further, most information is in English and is not translated. “No one-stop shop for resources.” |

| 2.3 Challenges with system navigation exist due to system fragmentation and constant change | System issues related to fragmentation, complexity, rigidity, over-medicalization, and constant change were noted to be challenging to contend with, and a strong need for coordination and navigation was identified. Even to navigate the system as a professional is frustrating and time-consuming. “The System is ‘strapped’ and we do not have the opportunity to truly engage with clients, this state of always being very ‘busy’ is detrimental to the system.” “Fractured system – caregivers do not know about programs and services available, rumours are spread about different care (ex: home care) some say it is good some say it is bad.” “It would be nice to have an integrated system.” Accessing the System from the outside is very difficult. “The System seems inhuman.” “Rules and regulations are not set up for families to navigate or flexible enough for them.” Across the province, services were identified as under-resourced, scattered, inequitable, and not comprehensive. The scattering was blamed on many services being diagnostic-specific. “The System is fragmented.” No one on the health-care team is currently responsible for addressing caregiver needs and no system approach is in place to support caregivers. Rather the system focuses on the person with the identified care need. Further, the patient’s medical needs are most often emphasized and functional needs overlooked. “The System focuses on the person requiring care (client), not on the caregiver.” “Lack of providers/trust to address caregiver needs.” “The System breaks down if someone is in care. System is not acknowledging what is needed.” |

| 2.4 Economic impact of caregiving is significant | There is lack of understanding of the costs of caregiving:

|

| 2.5 Policies, processes and procedures can create barriers | There is a clear need to consider the whole picture, avoid repetition, and understand the needs of the community before changing the system. “We need to set caregiving in the policy context, and show how it will save politicians money. The current system focuses on addressing acute health-care conditions versus the whole picture. The needs of individuals with chronic health conditions are less resourced and underserved. Policies are rigid and not adapted to meet client/caregiver needs; rules and regulations are not set up to support families. Inconsistent and conflicting policies need to be examined. “Government policy seems to be random.” Regarding physician involvement, the question of resources was raised particularly regarding: 1) whether or not there are a sufficient number of physicians with expert knowledge who work with and are willing to support such a complex population of patients, 2) time required to provide care, and 3) remuneration. Changing the physician pay structure was identified as a need so that doctors have time to care for elderly persons with complex needs. “More doctors, pay structure for doctors – salary rather than fee for services.” “Family doctor is consistent, but there are often 6 family doctors as a group. Trust issues arise when there are of different opinions.” “Family physicians are a “key to unlock the door.” The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FOIP) is a barrier to caregivers in advocating for the care recipient, as it does not allow for sharing of information. “FOIP is a limitation/barrier when caring for a family member. Some professionals will bend the rules and share information and some will not.” |

A number of recommendations were identified by participants to inform service delivery and research priorities. These included: 1) assisting caregivers in self-identifying and seeking support, 2) formalizing caregiver supports, 3) centralizing resources, 4) making system navigators available, and 5) preparing the next generation for caregiving (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Recommendations: Enhancing support for family caregivers of seniors with complex needs

| Themes | Findings |

|---|---|

| 1. Assist caregivers in self-identifying and seeking support | Health-care workers should help caregivers identify as such to gain access to resources that might help them maintain resilience. “... may not identify as caregiver to mother or spouse.” “Build meaning and resilience regarding the caregiver experience.” The importance of asking caregivers what assistance/resources they would want to help them manage their self-care was accentuated. Caregivers stated that relief, time off, and self-care would help allay not only the isolation they feel, but would allow for some physical, mental, and emotional renewal. “Caregivers are told to take care of themselves, but we don’t ask “what do you need to take care of yourself” “As a caregiver you would feel validated if the support team came in and said ‘What are your goals’” How can we both work together?” |

| 2. Formalize caregiver supports | Noted was a need for a standard and consistent procedure to engage family caregivers from the outset. “Active engagement of the caregiver from the 1st encounter.” “Consistency of service providers.” Caregivers clearly identified a need for more effective communication both between health-care providers, across the continuum of care, and with caregivers. “Information is power and it empowers.” There is a need to recognize that the client and caregiver form a dyadic unit. “Move our systems of support away from merely completing tasks to seeing the client/caregiver holistically.” Current social policies need to be reviewed, and appropriate social policies and supports need to be put in place/formalized to support family caregivers. “Social policies: 1) Need infrastructure to support caregivers, and 2) Current policies for financial support need modification.” |

| 3. Centralize resources for patients, caregivers, and health-care providers | A centralized location for caregivers to locate necessary resources for the client as well as themselves is needed. “Info/technology integration across systems.” “Bring resources closer to clients in the community.” “Allocate / distribute resources to the greatest areas of NEED.” “Need for coordination throughout the system.” A need for case managers to have access to necessary resources across several health-care domains was recognized. It was suggested that access by caregivers to care managers would be helpful in facilitating greater ease of navigation. “We need a case manager to manage resources for patients with dementia and complex needs.” “Caregivers need access to care managers to help navigate the system” “Build on what is already out there, not inventing new stuff.” |

| 4. Make system navigators available | The system needs to be restructured to make it more accessible for clients and their families. “Make the system less complicated; More responsive to patient and family needs.” “As workers in the system, we need to empathize and not assume caregivers know how to navigate the system.” |

| 5. Prepare the next generation for caregiving | Need to prepare younger adults for their potential future as a family caregiver. “Student investments – they are the future.” |

Day 2 recommendations for further research highlighted the need for: 1) literature reviews, 2) distillation of research priorities, and 3) development of an outline of a five-year program of research (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Recommendations for further research

| Theme | Findings |

|---|---|

| 1. Literature reviews | Literature reviews covering: 1) timing regarding when caregivers seek help, 2) why more research on caregivers is needed, 3) how caregivers identify themselves, 4) what has been shown to make a difference for caregivers, and 5) reasons as to why support for caregivers is not currently provided. |

| 2. Further distillation of initial research priorities | Recommendations for interventions for caregivers, such as 1) identification of ‘Goals of Care’ for family caregivers, 2) enhanced case management, 3) system navigation supports, 4) referral to the Alzheimer Society’s First Link program, 5) impactful change and funding models, and 6) knowledge exchange strategies to inform and sensitize current and upcoming generations of the realities of, and resources required, for caregiving. |

| 3. Outline of a 5-year program of research | Two key priorities were identified: 1) a longitudinal study of caregivers and their needs, recognizing variable journeys and the reciprocal relationships, and 2) an economic cost analysis examining high health-care users’ system versus caregiver costs (from an individual and system level perspective). |

DISCUSSION

Most seniors choose to live at home for as long they are able. (7) To help them do so, however, support from caregivers, which impacts all aspects of the carer’s life and can lead to caregiver burnout, is often required. This was identified in both the literature and conference findings regarding the Caregiver Experiences Theme #1, managing a multitude of tasks which can compromise caregivers’ ability to address personal needs.(2,4–7,10–12) Unfortunately, caregivers rarely self-identify, restricting the availability of timely supports that could prevent burnout. Attention needs to be placed on the needs of caregivers and provision of support that is rooted in respect, right to choose, and self-determination.(23)

There is increasing recognition that families and caregivers have assumed significant caregiving responsibilities,(24) necessitating the provision of adequate evidence-based support for caregivers. This was echoed in Facilitator Theme #3, caregivers are recognized by the system. A future goal is the inclusion of regional, provincial, national, and international strategies to improve outcomes for both older adults and their family caregivers.(15) Hallberg and Kristensson(25) noted in 2004 that frail, older people are at the intersection of divergent systems, including the acute care system, long term care system, and family caregiving. With acute and chronic complex health conditions affecting multiple body systems, a specialty approach to health care and a fragmented system fail to address the interdependency of physical, psychosocial, and functional health.(25) Fragmentation of the system was evident in Barriers Theme #3, challenges with system navigation exist due to fragmentation and constant change. As older adults with complex needs require care for an extended duration of time, a review of the capacity of the current health-care system to respond appropriately to the needs of older adults with complex needs and their caregivers is warranted. This is in keeping with findings from the conference, in that a holistic approach and preserved continuity of care are required to help older persons maintain quality of life and remain at home with as few interruptions as possible.

The capacity and resilience of family caregivers could be significantly improved through a variety of strategies. For example, new findings from our research recommendations include 1) assisting caregivers in self-identifying and seeking support, and 5) preparing the next generation for caregiving. In adopting interventions, however, it is essential to engage caregivers in designing, planning, and implementing them to avoid missing opportunities. As an example, a host of very rich literature describes family caregivers and their challenges,(24) with an emphasis on the importance of seeking patient and carer input when designing new case management programs. (26) There is the potential for better ways to foster case management–caregiver inclusion so that caregivers can maintain a supportive presence and improve their own outcomes.(27) Access to coaches, mentors, education, and training would also be advantageous. Telephone support groups, such as those offered through the Alzheimer Society, have resulted in a significant decrease in burden and depression, together with a significant increase in social support and knowledge among adult child caregivers (but not among spousal caregivers).(28) Health Education Programs, multi-component group interventions that focus on problem-based coping strategies, education, and support for caregivers, may also reduce caregiver burden.(29,30) For example, caregivers of frail older adults who receive a multi-component, interdisciplinary intervention reported overall better health and self-esteem than those in a control group.(31) Finally, the importance of centralizing resources and supports, providing supports to navigate through the health-care system, and advocating for policy change and financial supports for caregivers cannot be over-stated.

Limitations of Research

The conference utilized a purposeful integrated knowledge translation approach that was in keeping with the evidence-funnel within the knowledge-to-action cycle. The research presentations thus may have influenced participant responses in the discussions. Further, as the data were collected and analyzed as a single unit of analysis that intentionally facilitated co-production of knowledge and did not differentiate participant subgroups by role or geographic representation, the findings are limited in the specificity they offer about or to any one participant subgroup.

Future Research

Future research was highlighted to help shape a program of research in support of family caregivers of persons with complex needs. Research into case management, support groups, and health education programs is particularly warranted. Regarding case management, research needs to determined specific ways in which case managers can help caregivers, given that a systematic review has reported the efficacy of case management in decreasing caregiver burden and increasing caregiver satisfaction.(32) Research assessing the introduction of health education programs with school-and college-age students to better prepare them for the eventuality of caregiving is also an area of potential research. Another important area of future research is policy change. Consideration of the whole care picture instead of specific acute condition in seniors with complex needs, including the economic impact of caregiving, is warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

Family caregivers are an important, but overburdened and under-recognized, group within our health-care system, particularly those of seniors with complex needs. Caregivers require multifaceted supports to ensure that they can continue to provide care while maintaining their own wellbeing. A “one size fits all” model is not functional and collaborative practice will take different forms depending on the practice context, setting, family structure, and nature of the individual’s needs. Such an approach requires that practitioners seek out, integrate, and value, as a partner, the input and engagement of individual/family/community in designing and implementing care/services.

Understanding of the psychosocial and environmental context, which builds on the resilience of the older adult-family caregiver unit, is required to address the needs of community-dwelling older adults. There is a sense that we are spending more on health, social, home-based, and community services than ever before, yet there is the recognition that older adults and their caregivers still find it challenging to access the right services, in the right place, at the right time. The success of interventions will depend on the degree of caregiver involvement, the extent to which programs are individualized, the accessibility of information and coaching, the availability of system navigation supports, and the type and impact of the behaviour of the care recipient. Linkages need to occur amidst such programs in order to provide the best services to meet the unique needs of caregivers. Critical success factors in seniors’ health services redesign include gaining a better understanding of family caregiver expectations and ways to foster caregiver resilience and strength so that they can maintain a supportive presence. The results of this meeting will help shape future research and interventions regarding support for family caregivers. Many have already been developed.

A discovery toolkit for health-care providers supporting family caregivers was produced as an output from the conference. An inventory of caregiver resources has been created and this is being disseminated widely for caregivers. A caregiver education module for case managers has been introduced in the Building Case Management of Dementia Capacity in Homecare Initiative in Edmonton Zone which includes assessment of caregiver needs and referrals to community supports. This will be spread across continuing care under the Continuing Care Dementia strategy. A Covenant Health Caregiver symposium on ‘Caregiver Supports in Acute and Continuing Care’ was held August 31, 2016. A report is being prepared of findings from that symposium which will suggest future directions. A grant has been obtained to synthesize the proceedings of the symposium, and engage acute and continuing care facilities in providing supports for family caregivers of seniors. The findings of this project have also had reach into primary care with a Primary Care Network Geriatrics Hub research project which has included screening of caregivers for risk factors and education of staff on caregiver-related issues.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bohnert N, Chagnon J, Dion P. Population Projections for Canada (2013 to 2063), Provinces and Territories (2013 to 2038) Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-520-x/91-520-x2014001-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler-Jones D. Report on State of Public Health in Canada 2010: Growing older– adding life to years. Ottawa: Department of Public Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer Society of Canada. A new way of looking at the impact of dementia in Canada. Toronto: Alzheimer Society of Canada; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.alzheimer.ca/en/cornwall/Awareness/A-new-way-of-looking-at-dementia. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eales J, Kim C, Fast J. A snapshot of Canadians caring for persons with dementia: the toll it takes. Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta Research on Aging, Policies and Practice; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinha M. Results from General Social Survey: Portrait of Caregivers. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2013001-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Council of Canada. Seniors in need, caregivers in distress: what are the home care priorities for seniors in Canada? Toronto: Health Council of Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner A, Findlay L. Informal caregiving for seniors. Health Reports. 2012;23(3):33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Supporting informal caregivers — the heart of home care. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollander M, Guiping L, Chappell N. Who cares and how much? The imputed economic contribution to the Canadian healthcare system of middle-aged and older unpaid caregivers providing care to the elderly. Healthcare Q. 2009;12(2):4. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stajduhar K, Funk L, Toye C, et al. Part 1: Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998–2008) Palliative Med. 2010;24(6):573–93. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumont S, Jacobs P, Fassbender K, et al. Costs associated with resource utilization during the palliative phase of care: a Canadian perspective. Palliative Med. 2009;23(8):708–17. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smetanin P, Kobak P, Briante C, et al. Rising tide: the impact of dementia in Canada 2008 to 2038. North York: RiskAnalytica; 2009. Retrieved from: http://www.alzheimer.ca/~/media/Files/national/Advocacy/Rising_Tide_RiskAnalytica.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudgeon S. Rising tide: the impact of dementia on Canadian society. Toronto: Alzheimer Society of Canada; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.alzheimer.ca/~/media/Files/national/Advocacy/ASC_Rising_Tide_Full_Report_e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parmar J, Jette N, Brémault-Phillips S, et al. Supporting people who care for older family members. CMAJ. 2014;186(7):487. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Institute of Aging Strategic Research priorities, 2013–2018. Montreal: CIHR; n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown J, Isaacs D, Wheatley MJ. The World Café: shaping our futures through conversations that matter. San Francisco, CA: Barrett-Koehler; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–40. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neergaard A, Olesen F, Andersen RS, et al. Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.QSR International. NVivo 9 software. Victoria, Australia: QSR; n.d. Retrieved from: http://www.qsrinternational.com. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canadian Caregiver Coalition. A framework for a Canadian caregiver strategy. Ottawa: The Canadian Caregiver Coalition; 2008. Caregiver strategy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bookman A, Harrington M. Family caregivers: a shadow workforce in the geriatric healthcare system. J Health Politics, Policy Law. 2007;32(6):1005–41. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2007-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallberg RH, Kristensson J. Preventative home care for frail older people: a review of recent case management studies. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(s2):112–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sargent P, Pickard S, Sheaff R, et al. Patient and carer perceptions of case management for long term conditions. Health Soc Care Community. 2007;15(6):511–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandberg M. DMed Thesis. Lund, Sweden: Lund University; 2013. Case management for frail older people. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith T, Toseland RW. The effectiveness of a telephone support program for caregivers of frail older adults. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(5):620–29. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toseland R, McCallion P, Smith T, et al. Supporting caregivers of frail older adults in an HMO setting. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(3):349–64. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labrecque M, Peak T, Toseland RW. Long-term effectiveness of a group program for caregivers of frail elderly veterans. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62(4):575–88. doi: 10.1037/h0079385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aggar C, Rolandson S, Cameron ID. Reactions to caregiving during an intervention targeting frailty in community living older people. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.You E, Dunt D, Doyle C, et al. Effects of case management in community aged care on client and carer outcomes: a systematic review of randomized trials and comparative observational studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:395. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]