Abstract

Background

The Romhilt‐Estes point score system (RE) is an established ECG criterion for diagnosing left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). In this study, we assessed for the first time, whether RE and its components are predictive of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) independent of left ventricular (LV) mass.

Methods

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) cases occurring between 2002 and 2014 in a Northwestern US metro region (catchment area approx. 1 million) were compared to geographic controls. ECGs and echocardiograms performed prior to the SCA and those of controls were acquired from the medical records and evaluated for the ECG criteria established in the RE score and for LV mass.

Results

Two hundred forty‐seven SCA cases (age 68.3 ± 14.6, male 64.4%) and 330 controls (age 67.4 ± 11.5, male 63.6) were included in the analysis. RE scores were greater in cases than controls (2.5 ± 2.1 vs. 1.9 ± 1.7, p < .001), and SCA cases were more likely to meet definite LVH criteria (18.6% vs. 7.9%, p < .001). In a multivariable model including echocardiographic LVH and LV function, definite LVH remained independently predictive of SCA (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.16–3.59, p = .013). The model was replicated with the individual ECG criteria, and only SV 1.2 ≥ 30 mm and delayed intrinsicoid deflection remained significant predictors of SCA.

Conclusion

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) as defined by the RE point score system is associated with SCA independent of echocardiographic LVH and reduced LV ejection fraction. These findings support an independent role for purely electrical LVH, in the genesis of lethal ventricular arrhythmias.

Keywords: electrocardiography, left ventricular hypertrophy, sudden cardiac arrest

1. Introduction

There are over 300,000 estimated deaths annually in the United States due to sudden cardiac arrest (SCA; Mozaffarian et al., 2015), thus identifying subjects at increased risk for SCA has been a focus of intensive research with the goal of reducing this burden (Bardy et al., 2005; Buxton et al., 1999; Epstein et al., 2008; Moss et al., 1996, 2002). The 12‐lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is a widely available diagnostic tool with several depolarization and repolarization abnormalities already associated with increased risk of SCA (Algra, Tijssen, Roelandt, Pool, & Lubsen, 1991; Aro et al., 2011; Chugh et al., 2009; Darouian et al., 2016; Straus et al., 2006; Teodorescu et al., 2001). Although the 12‐lead ECG has limited ability to detect increased left ventricular (LV) mass, we have recently demonstrated that electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) by Sokolow–Lyon voltage criteria was associated with SCA independent of anatomic LVH (Narayanan et al., 2014). Therefore, adverse electrical LV remodeling in the absence of anatomic remodeling is emerging as a potentially distinct phenomenon from anatomic LV hypertrophy (Aro & Chugh, 2016).

The Romhilt‐Estes point score system (RE score) was first presented in 1968 as a new method for diagnosing LVH on the ECG (Romhilt & Estes, 1968). In contrast with traditional voltage‐based LVH criteria, the RE score takes into account multiple ECG abnormalities. It is made up of nine individual criteria determined from the 12‐lead ECG, with RE score of 4 being labeled as probable LVH and a score of 5 or greater as definite LVH (Romhilt & Estes, 1968). In addition to diagnosing LVH, the RE score has been shown to predict adverse cardiovascular events and all‐cause mortality (Estes, Zhang, Li, Tereschenko, & Soliman, 2015; Estes, Zhang, Li, Tereshchenko, & Soliman, 2015), and we recently demonstrated that one component of the RE score, delayed intrinsicoid deflection, was independently predictive of SCA (Darouian et al., 2016). However, little data exists on the performance of the other individual components, or the RE score as a whole as a predictor of SCA. In this study, we explored the association of RE score and its individual components with SCA, and compared it to other traditional voltage‐based LVH criteria. Moreover, we studied whether this association with SCA was independent of increased left ventricular mass.

2. Methods

2.1. Ascertainment of subjects

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Cedars‐Sinai Medical Center, Oregon Health and Science University, and all other relevant health systems.

We evaluated the relationship of the RE score and SCA from the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study (Oregon SUDS). The details of this ongoing study have been published previously (Chugh et al., 2009; Darouian et al., 2016; Narayanan et al., 2014; Teodorescu et al., 2001). Cases and controls in the study were enrolled from the Portland, Oregon metropolitan area consisting of a population of approximately one million individuals. SCA was defined as a sudden unexpected pulseless condition in witnessed individuals within 1 hr of symptom onset; and within 24 hr of last being seen in a normal state of health for unwitnessed cases. Cases with known terminal illnesses, traumatic deaths, drug overdoses, or other known noncardiac conditions were excluded. Cases of SCA were identified via emergency medical services, local hospitals, and the medical examiner's office, and then reviewed as part of an in‐house adjudication process by three physicians prior to inclusion in the study. Control subjects recruited for this study had visited local cardiology clinics, were transported via EMS for symptoms concerning for cardiac ischemia, had undergone coronary angiography, or were members of a regional health maintenance organization. Since coronary artery disease (CAD) is responsible for most SCA cases, also majority of controls enrolled in this study had established CAD. CAD was defined as a history of a myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, or ≥50% occlusion of a major coronary artery. Between February 1, 2002 and September 10, 2014, 3,020 SCA cases (mean age 62.7 years, 67.5% male) with medical records available were identified in the Oregon SUDS. A total of 682 of these subjects had an ECG performed prior to cardiac arrest, and following exclusion of those without an echocardiogram, and those with severe aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and Wolff‐Parkinson‐White syndrome 272 cases and 351 controls remained. Individuals with left bundle branch block and paced rhythms were excluded, leaving 247 cases and 330 controls available for the analysis.

2.2. ECG and echocardiographic analysis

All subjects enrolled in this study were required to have both ECG and echocardiographic information available for analysis. For cases of SCA, ECGs, and echocardiogram reports performed as part of routine clinical practice were obtained from patients’ medical charts; if more than one was available, the test closest to the SCA event was selected for analysis. Twenty‐nine survivors of SCA were also included in the analysis. For controls, ECG and echocardiographic data were obtained from patients’ medical charts available prior to enrollment, as for cases. For controls, ECGs were also performed at time of enrollment in the study. Two trained physicians reviewed standard 12‐lead ECG recordings at 25 mm/s paper speed and 10 mm/mV amplitude. Heart rate, QRS durations, and QRS axis were recorded as standard values from the ECG recording. Additional ECG waveforms, intrinsicoid deflection, left atrial abnormality, and strain were measured manually by a trained physician research (N.D.). An experienced cardiologist (A.A.) remeasured these manual recordings in a subset, to assess interobserver variability with a kappa value of .89.

We evaluated the presence of echocardiographic LVH using LV mass indices >134 g/m2 in men and >110 g/m2 in women (Devereux et al., 1984). LV mass was calculated using the following formula: (LV mass = 0.8(1.04([LVIDD + PWd + IVSd]3 − [LVIDD]3)) + 0.6 g) (Devereux et al., 1984; LVIDD: left ventricular internal diameter in diastole, PWd: posterior wall thickness in diastole, IVSd: interventricular septal thickness in diastole). We then corrected for body surface area to obtain LV mass index values. Severe LV dysfunction was defined as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%.

2.3. Electrocardiographic LVH

ECGs were measured for the components of the RE score as follows: R or S wave in any limb lead ≥20 mm, S wave in leads V 1 or V 2 ≥ 30 mm, R wave in V 5 or V 6 ≥ 30 mm, left axis deviation ≤ −30°, and QRS duration ≥ 0.09 s. Left atrial abnormality was defined as a terminal negative deflection of the P wave in V 1 ≥ 1 mm in amplitude and ≥0.04 s in duration, ST changes of strain pattern were noted with asymmetric ST depression and T wave inversion opposite of the QRS in lateral precordial leads of V 5 or V 6, and delayed intrinsicoid deflection defined as ≥0.05 s from onset of QRS to peak of the R wave in leads V 5 or V 6. ECGs with atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter were considered null for the presence or absence of left atrial abnormality. Positive voltage criteria in limb leads, SV1,2, or RV5,6 were awarded 3 points. ST changes consistent with strain were given 3 points in subjects not on digoxin and 1 point otherwise. The remainder of the findings was given the following scores: 3 points for left atrial abnormality, 2 points for left axis deviation, 1 point for QRS duration, 1 point for delayed intrinsicoid deflection. Probable LVH and definite LVH were defined as RE scores of 4 and ≥5, respectively (Romhilt & Estes, 1968). Sokolow–Lyon LVH Criteria (SV1 + RV5,6 ≥ 35 mm) and Cornell Criteria (RaVL + SV3 ≥ 20 mm in females, ≥28 mm in males) were measured in each ECG as well (McLenachan, Henderson, Morris, & Dargie, 1987; Sokolow & Lyon, 1949).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Case–control comparisons were performed using Pearson's chi‐square tests and independent samples t‐tests for categorical and quantitative variables, respectively. Multiple logistic regression models were used to perform multivariable analysis including variables found to be statistically significant in univariate analysis. We evaluated the agreement between the RE score and Echo LVH using the Kappa statistic. Values were considered statistically significant when p ≤ .05. Data is presented as n (%) or mean ± SD.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Cases of SCA (n = 247, age: 68.3 ± 14.6, male: 64.4%) were compared to controls (n = 330, age: 67.4 ± 11.5, male: 63.6%) as demonstrated in Table 1. Cases were more likely to have a history of diabetes mellitus (49.4% vs. 33.0%, p < .001) than controls. Cases were also noted to have significantly higher resting heart rates than controls. Echocardiographic findings of significance included lower ejection fractions (50.8% ± 15.7 vs. 54.9% ± 12.6, p = .001) and greater LV mass indices (120.3 g/m2 ± 42.6 vs. 100.5 g/m2 ± 32.5, p < .001) in cases than controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sudden cardiac arrest cases and control subjects

| Case (n = 247) | Control (n = 330) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.3 ± 14.6 | 67.4 ± 11.5 | .410 |

| Male | 159 (64.4%) | 206 (63.6%) | .845 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.4 ± 10.1 | 30.0 ± 6.8 | .621 |

| Hypertension | 197 (79.8%) | 251 (76.1%) | .292 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 122 (49.4%) | 109 (33.0%) | <.001 |

| History of tobacco use | 135 (54.7%) | 172 (52.1%) | .546 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 100.4 ± 20.8 | 97.3 ± 17.8 | .053 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 77.4 ± 17.7 | 69.3 ± 15.6 | <.001 |

| LV EF (%) | 50.8 ± 15.7 | 54.9 ± 12.6 | .001 |

| Severe LV dysfunction | 55 (22.5%) | 35 (10.7%) | <.001 |

LV, left ventricular; EF, ejection fraction.

Data presented as n (%) or mean ± SD.

3.2. RE score and anatomic left ventricular hypertrophy

Of the sample population, 440 subjects (76.3%) had no forms of LVH per RE score (Table 2). A score of 4, or probable LVH, was present in 65 subjects (11.3%) and a score of ≥5, or definite LVH, was present in 72 subjects (12.5%). In subjects with an RE score of 4, anatomic echo‐derived LVH was diagnosed in 15.8% of the population. The average LV mass index of this group was 106.8 g/m2 ± 31.8. In subjects with definite LVH, echo‐derived LVH was present in 48.5% of this group with a kappa value of .17 indicating relatively low level of agreement between LVH by RE score and echocardiography. LV mass index in subjects with definite LVH was 130.3 g/m2 ± 45.2 as compared to 105.4 g/m2 ± 36.1 (p < .001) in subjects with RE scores ≤4.

Table 2.

Echo findings and RE scores of sudden cardiac arrest cases and control subjects

| Case (n = 247) | Control (n = 330) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 120.3 ± 42.6 | 100.5 ± 32.5 | <.001 |

| Echocardiographic LVHa | 82 (37.1%) | 59 (18.7%) | <.001 |

| RE score | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | <.001 |

| RE score ≤3 | 172 (69.6%) | 268 (81.2%) | .001 |

| Probable LVH (RE = 4) | 29 (11.7%) | 36 (10.9%) | .755 |

| Definite LVH (RE ≥ 5) | 46 (18.6%) | 26 (7.9%) | <.001 |

RE, Romhilt‐Estes point score; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

Data presented as n (%) or mean ± SD.

Defined as LV mass indices >134 g/m2 in men and >110 g/m2 in women. Data unavailable for 15 controls and 26 cases.

3.3. RE score and SCA

RE scores were found to be significantly higher in cases than controls (2.5 ± 2.1 vs. 1.9 ± 1.7, p < .001). The probable LVH sub group with RE score of 4 did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference between cases and controls. However, an RE score of ≥5 was more prevalent in cases than controls (18.6% vs. 7.9%, p < .001), with the unadjusted risk of SCA being 2.7 (95% CI: 1.6–4.5, p < .001).

In a multivariable analysis with age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, severe LV dysfunction, and heart rate in the model, RE score ≥5 was associated with a significant risk of SCA (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.2–3.6, p = .006; Table 3). Anatomic LVH was then added to the model to evaluate whether the risk of SCA associated with the RE score was dependent on increased LV mass. In this model, RE score ≥5 remained a significant independent predictor of SCA (OR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.2–3.6, p = .013). In the same model, echo‐derived anatomic LVH was associated with increased risk of SCA (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.4–3.2, p = .001).

Table 3.

Multivariate model evaluating risk of SCA including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart rate, and severe LV dysfunction. Includes second model with Echo LVH added as variable

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | .060 | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | .094 |

| Male | 1.11 (0.76–1.60) | .597 | 1.30 (0.87–1.94) | .193 |

| Hypertension | 1.08 (0.69–1.68) | .731 | 1.15 (0.72–1.84) | .566 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.84 (1.27–2.65) | .001 | 1.72 (1.17–2.52) | .006 |

| Heart rateb | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <.001 |

| Severe LV dysfunction | 1.70 (1.03–2.81) | .039 | 1.48 (0.87–2.50) | .145 |

| RE score ≥5 | 2.12 (1.24–3.64) | .006 | 2.04 (1.16–3.59) | .013 |

| Echo LVH | 2.10 (1.38–3.22) | .001 |

LV, left ventricular; RE, Romhilt‐Estes point score.

OR presented as increased risk per 1 year.

OR presented as increased risk per 1 bpm.

3.4. Individual components of the RE score and SCA

As demonstrated in Table 4, several of the individual components of the RE score were more predominant in cases of SCA than controls. SV1–2 ≥ 30 mm was present in 4.9% of cases as compared to 1.2% of controls (p = .008). ST segment changes consistent with “strain” pattern were more common in cases as well in individuals on and off digoxin. Left atrial abnormality (p = .044) and delayed intrinsicoid deflection (p = .003) were also found significantly more common in SCA as well.

Table 4.

Case–control comparison evaluating components of RE score, and the risk of SCA associated with individual components

| RE score variable | Case (n = 247) | Control (n = 330) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limb lead R/S ≥ 20 mm | 5 (2.0%) | 6 (1.8%) | 1.12 (0.34–3.70) | .858 |

| SV1–2 ≥ 30 mm | 12 (4.9%) | 4 (1.2%) | 4.16 (1.33–13.06) | .008 |

| RV5–6 ≥ 30 mm | 5 (2.0%) | 4 (1.2%) | 1.68 (0.45–6.34) | .436 |

| Strain pattern not on digoxin | 11 (4.5%) | 4 (1.2%) | 3.80 (1.19–12.08) | .015 |

| Strain pattern on digoxin | 25 (10.2%) | 16 (4.9%) | 2.21 (1.15–4.24) | .015 |

| Left atrial abnormalitya | 68 (30.2%) | 71 (22.5%) | 1.49 (1.01–2.19) | .044 |

| QRS axis ≤ −30° | 40 (16.2%) | 45 (13.6%) | 1.22 (0.77–1.94) | .391 |

| QRS duration ≥ 0.09 s | 170 (68.8%) | 212 (64.2%) | 1.23 (0.87–1.75) | .249 |

| Delayed intrinsicoid deflection | 55 (22.3%) | 43 (13.0%) | 1.91 (1.23–2.97) | .003 |

OR, odds‐ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Data presented as n (%).

Confined to 225 cases and 315 controls in sinus rhythm.

We performed similar multivariable analysis with a model including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, severe LV dysfunction, heart rate, and anatomic LVH with each of the RE score criteria added individually in this model. As demonstrated in Table 5, only SV1–2 ≥ 30 mm and delayed intrinsicoid deflection remained independent predictors of SCA with echo‐derived LVH in the model.

Table 5.

Multivariate model to evaluate risk of SCA with individual RE criteria addeda

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Limb lead R/S ≥ 20 mm | 1.16 (0.28–4.74) | .836 |

| SV1–2 ≥ 30 mm | 4.86 (1.26–18.76) | .022 |

| RV5–6 ≥ 30 mm | 2.17 (0.54–8.73) | .276 |

| Strain pattern not on digoxin | 2.03 (0.59–6.95) | .261 |

| Strain pattern on digoxin | 1.70 (0.84–3.43) | .141 |

| Left atrial abnormality | 1.42 (0.92–2.19) | .116 |

| QRS axis ≤ −30° | 0.88 (0.52–1.50) | .642 |

| QRS duration ≥ 0.09 s | 1.09 (0.73–1.64) | .671 |

| Delayed intrinsicoid deflection | 1.90 (1.16–3.11) | .011 |

Model with age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, severe LV dysfunction, heart rate, and echo LVH with each RE score criteria added separately.

3.5. Comparison of RE score with other LVH criteria

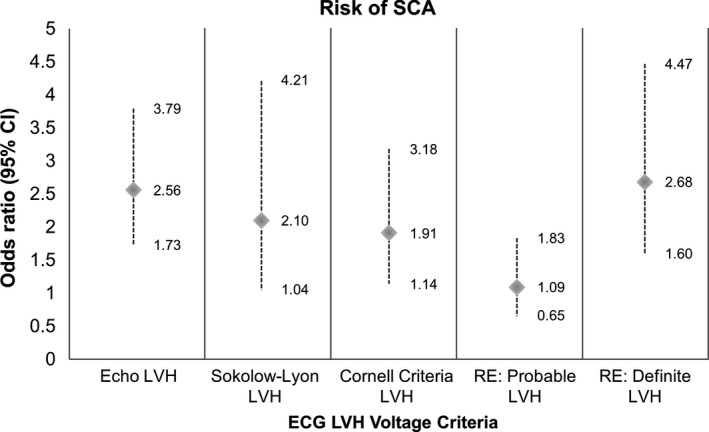

In comparison to the other well‐established electrocardiographic LVH criteria, Sokolow–Lyon and Cornell criteria, definite LVH as determined by the RE score ≥5 carried the greatest risk of SCA (Figure 1). Sokolow–Lyon criteria and Cornell criteria preformed similarly regarding the risk for SCA (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.0–4.2, p = .034 and OR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.1–3.2, p = .012, respectively). In predicting SCA, the c‐statistic for definite LVH was noted to be 0.55 (95% CI: 0.51–0.59, p = .027) as compared to 0.52 (95% CI: 0.48–0.56, p = n.s.) for the Sokolow–Lyon criteria and 0.53 (95% CI: 0.49–0.57, p = n.s.) for the Cornell criteria. Probable LVH by the RE score was not associated with a statistically significant risk of SCA.

Figure 1.

Univariate odds ratio of SCA with ECG LVH criteria

3.6. ECG LVH and intraventricular conduction delays

In a subgroup of patients, all subjects with QRS duration ≥120 ms were excluded from the analysis to evaluate whether any significant conduction delay would affect the findings. In this subgroup, 35 cases of 214 (16.4%) were noted to have an RE score ≥5 as compared to 21 controls of 292 (7.2%; p = .001). In a multivariate analysis that included age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, severe LV dysfunction, heart rate, and anatomic LVH, definite LVH was found to be a significant predictor of SCA (OR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.01–3.58, p = .046).

4. Discussion

There is emerging evidence suggesting that electrocardiographic LVH is a risk factor for SCA independent of increased LV mass (Aro & Chugh, 2016). In this study, we evaluated this relationship using the Romhilt‐Estes point score system as the criterion for diagnosis of electrocardiographic LVH. Our results demonstrate a significant association with definite LVH, or RE score ≥5, and SCA. High RE score remained a significant predictor of SCA independent of the echocardiographic LVH providing further evidence that electrical and anatomic LVH are somewhat distinct clinical entities. High RE score also appeared to be a better predictor than purely voltage‐based criteria. We also demonstrate that of the nine variables assessed in the RE score, SV1–2 ≥ 30 mm and delayed intrinsicoid deflection remained significantly associated with SCA independent of anatomic LVH.

Increased LV mass has been previously established as a risk factor for SCA (Verdecchia et al., 1998), but recent evidence suggests that electrocardiographic LVH is an additional risk factor for SCA with a potentially independent mechanism (Narayanan et al., 2014). Our results support the concept that some patients have adverse, purely electrical LV remodeling as a phenomenon distinct from anatomic LVH. In this study, we evaluated whether RE score which takes into account several ECG patterns associated with SCA, leads to the improved detection of SCA risk (Darouian et al., 2016; Teodorescu et al., 2001). LVH according to the RE score was associated with a greater than 2.5‐fold risk of SCA, which was higher than with more widely used Sokolow–Lyon and Cornell criteria based purely on QRS amplitudes. However, it is unlikely for this increase in risk to be secondary due to better detection of anatomic LVH as the kappa statistic, measuring agreement between electrocardiographic and echocardiographic diagnosis of LVH, was low.

When evaluating the individual components of the RE score in univariate analysis, five of the nine variables, namely strain pattern (with or without digoxin), deep S wave in V 1–2, left atrial abnormality, and delayed intrinsicoid deflection, were found to be associated with SCA. However, when anatomic LVH was included in the model, only SV1–2 ≥ 30 mm and delayed intrinsicoid deflection remained significant predictors of SCA. The S wave in V 1–2 is a component of many ECG LVH criteria including both Sokolow–Lyon and the RE score (Romhilt & Estes, 1968; Sokolow & Lyon, 1949), but there is little reported on the significance of the S wave in V 1–2 beyond its relationship with left ventricular hypertrophy. In contrast, the association between delayed intrinsicoid deflection and SCA has been recently described (Darouian et al., 2016).

Strain was found to be associated with SCA, but this risk was not found to be independent of anatomic LVH in a multivariate model. Strain pattern has been previously identified as a significant predictor of a wide range of clinical conditions including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cardiovascular mortality, and sudden cardiac death (Kannel, Gordon, Castelli, & Margolis, 1970; Larsen et al., 2002; Okin et al., 2004, 2004, 2006, 2009; Pringle, Macfarlane, McKillop, Lorimer, & Dunn, 1989). The pathophysiology behind strain has been proposed to be secondary to a wide spectrum of etiologies including myocardial hypertrophy, subendocardial ischemia, myocardial fibrosis, and alterations in conduction velocity with the precise mechanism not yet known (Anderson et al., 2000; Bacharova, Szathmary, & Mateasik, 2013; Devereux & Reichek, 1982; Eranti et al., 2014; Okin et al., 2006; Pringle et al., 1989; Rembert, Kleinman, Fedor, Wechsler, & Greenfield, 1978; Schocken, 2014; Shah et al., 2014). However, based on this study, the adverse prognosis of strain seems to be associated with underlying structural cardiac pathology, and not to strain pattern per se. Left atrial abnormality on the 12‐lead ECG has also been associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes including development of atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, and all‐cause mortality(Eranti et al., 2014; Tereshchenko et al., 2014), and in this study, it was associated with SCA in the univariate analysis. However, this finding lost statistical significance when included in multivariate analysis including left ventricular hypertrophy, suggesting a likely overlap between left atrial abnormality and anatomic LVH in the mechanism of SCA risk.

Beyond SCA, the RE score has been studied for its relationship with additional adverse clinical outcomes. Recently, Estes et al. (2015) reported that increasing RE scores were associated with greater risk of all‐cause mortality. Definite LVH, or a score of ≥5 was found to have a greater than fourfold risk of mortality as compared to a score of 0 (Estes et al., 2015). In that study, it was also found that left atrial abnormality, QRS amplitude, ST changes consistent with strain pattern, and delayed intrinsicoid deflection were all independently predictive of all‐cause mortality (Estes et al., 2015). The RE score was also found to be predictive of cardiovascular events including coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and stroke (Estes et al., 2015), but anatomic LVH was not accounted for in this study.

Our community‐based study design has some notable strengths including the prospective methods of ascertaining subjects for evaluation. Since CAD is responsible of the vast majority of SCA cases, we used a research design that included a majority of controls with CAD, which enabled us to evaluate differences between the two populations specific to SCA. However, the case–control approach also has certain inherent limitations. A large subset of the initial population was excluded from this study due to missing clinical variables, ECG, and echo information. These exclusions are expected, as studies such as echocardiography are not a part of routine medical care in subjects without cardiac risk factors. This does create a form of selection bias since those with echocardiographs performed prior to the SCA were more likely to have a cardiac history as compared to the excluded cases with no echocardiographs performed. An additional limitation of our study due to the number of excluded subjects is the relatively small subset of our population with strain present, and it is possible that with a larger sample size some further significant differences could have been found. The study was also limited in that more sensitive tools for assessing LV mass including cardiac MRI were not available for the diagnosis for anatomic LVH.

5. Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that definite LVH as defined by the RE point score system is associated with SCA independent of echocardiographic LVH. In comparison to other well‐known ECG voltage‐based LVH criteria, the RE score conferred higher risk of SCA. Of the individual variables of the RE score, two remained independent predictors of SCA independent of echocardiographic LVH. These results further support electrical remodeling occurring as an isolated phenomenon in some patients, also contributing to increased risk of SCA distinctively from anatomic LVH.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of all emergency medical services personnel (American Medical Response, Portland/Gresham fire departments), the Oregon State Medical Examiner's office and the hospitals in the Portland Oregon metro area.

Darouian N, Aro AL, Narayanan K, et al. The Romhilt‐Estes electrocardiographic score predicts sudden cardiac arrest independent of left ventricular mass and ejection fraction. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2017;22:e12424 10.1111/anec.12424

Funding information

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Number: R01 HL105170, R01 HL088416, R01HL122492. Dr. Chugh holds the Pauline and Harold Price Chair in Cardiac Electrophysiology at Cedars‐Sinai, Los Angeles.

References

- Algra, A. , Tijssen, J. G. , Roelandt, J. R. , Pool, J. , & Lubsen, J. (1991). QTc prolongation measured by standard 12‐lead electrocardiography is an independent risk factor for sudden death due to cardiac arrest. Circulation, 83, 1888–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, H. V. , Stokes, M. J. , Leon, M. , Abu‐Halawa, S. A. , Stuart, Y. , & Kirkeeide, R. L. (2000). Coronary artery flow velocity is related to lumen area and regional left ventricular mass. Circulation, 102(1), 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro, A. L. , Anttonen, O. , Tikkanen, J. T. , Junttila, M. J. , Kerola, T. , Rissanen, H. A. , … Huikuri, H. V. (2011). Intraventricular conduction delay in a standard 12‐lead electrocardiogram as a predictor of mortality in the general population. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 4, 704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro, A. L. , & Chugh, S. S. (2016). Clinical diagnosis of electrical versus anatomic left ventricular hypertrophy: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 4, e003629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacharova, L. , Szathmary, V. , & Mateasik, A. (2013). QRS complex and ST segment manifestations of ventricular ischemia: The effect of regional slowing of ventricular activation. Journal of Electrocardiology, 6, 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardy, G. H. , Lee, K. L. , Mark, D. B. Poole, J. E. , Packer, D. L. , Boineau, R. , … Ip, J. H. (2005). Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator for congestive heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine, 352, 225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, A. E. , Lee, K. L. , Fisher, J. D. , Josephson, M. E. , Prystowsky, E. N. , & Hafley, G. (1999). A Randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. New England Journal of Medicine, 341, 1882–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, S. S. , Reinier, K. , Singh, T. , Uy‐Evanado, A. , Socoteanu, C. , Peters, D. , … Jui, J. (2009). Determinants of prolonged QT interval and their contribution to sudden death risk in coronary artery disease: The Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. Circulation, 119, 663–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darouian, N. , Narayanan, K. , Aro, A. L. , Reinier, K. , Uy‐Evanado, A. , Teodorescu, C. , … Chugh, S. S. (2016). Delayed intrinsicoid deflection of the QRS complex is associated with sudden cardiac arrest. Heart Rhythm: The Official Journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, 4, 927–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, R. B. , Lutas, E. M. , Casale, P. N. , Kligfield, P. , Eisenberg, R. R. , Hammond, I. W. , … Laragh, J. H. (1984). Standardization of M‐mode echocardiographic left ventricular anatomic measurements. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 4, 1222–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, R. B. , & Reichek, N. (1982). Repolarization abnormalities of left ventricular hypertrophy. Clinical, echocardiographic and hemodynamic correlates. Journal of Electrocardiology, 1, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, A. E. , Dimarco, J. P. , Ellenbogen, K. A. Mark Estes N. A. III, Freedman, R. A. , Gettes, L. S. , … Sweeney, M. O. (2008). ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for Device‐Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: Executive summary. Heart Rhythm: The Official Journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, 5, 934–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eranti, A. , Aro, A. L. , Kerola, T. , Anttonen, O. , Rissanen, H. A. , Tikkanen, J. T. , … Huikuri, H. V. (2014). Prevalence and prognostic significance of abnormal P terminal force in lead V1 of the ECG in the general population. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 6, 1116–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes, E. H. , Zhang, Z. M. , Li, Y. , Tereschenko, L. G. , & Soliman, E. Z. (2015). The Romhilt‐Estes left ventricular hypertrophy score and its components predict all‐cause mortality in the general population. American Heart Journal, 1, 104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes, E. H. , Zhang, Z. M. , Li, Y. , Tereshchenko, L. G. , & Soliman, E. Z. (2015). Individual components of the Romhilt‐Estes left ventricular hypertrophy score differ in their prediction of cardiovascular events: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. American Heart Journal, 6, 1220–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel, W. B. , Gordon, T. , Castelli, W. P. , & Margolis, J. R. (1970). Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of coronary heart disease. The Framingham study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 72(6), 813–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, C. T. , Dahlin, J. , Blackburn, H. , Scharling, H. , Appleyard, M. , Sigurd, B. … Schnohr, P. (2002). Prevalence and prognosis of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy, ST segment depression and negative T‐wave; the Copenhagen City Heart Study. European Heart Journal, 23(4), 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLenachan, J. M. , Henderson, E. , Morris, K. I. , & Dargie, H. J. (1987). Ventricular arrhythmias in patients with hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy. New England Journal of Medicine, 13, 787–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, A. J. , Hall, W. J. , Cannom, D. S. , Daubert, J. P. , Higgins, S. L. , Klein, H. , … Heo, M. (1996). Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators. New England Journal of Medicine, 335, 1933–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, A. J. , Zareba, W. , Hall, W. J. , Klein, H. , Wilber, D. J. , Cannom, D. S. , … Andrews, M. L. (2002). Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. New England Journal of Medicine, 346, 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian, D. , Benjamin, E. J. , Go, A. S. , Lloyd‐Jones, D. M. , Benjamin, E. J. , Berry, J. D. , … Turner, M. B. (2015). Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 131, e29–e322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, K. , Reinier, K. , Teodorescu, C. , Uy‐Evanado, A. , Chugh, H. , Gunson, K. , … Chugh, S. S. (2014). Electrocardiographic versus echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and sudden cardiac arrest in the community. Heart Rhythm: The Official Journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, 11, 1040–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okin, P. M. , Devereux, R. B. , Nieminen, M. S. , Jern, S. , Oikarinen, L. , Viitasalo, M. , … Dahlöf, B. (2006). Electrocardiographic strain pattern and prediction of new‐onset congestive heart failure in hypertensive patients: The Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study. Circulation, 1, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okin, P. M. , Devereux, R. B. , Nieminen, M. S. , Jern, S. , Oikarinen, L. , Viitasalo, M. , … Dahlöf, B. (2004). Electrocardiographic strain pattern and prediction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension, 1, 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okin, P. M. , Oikarinen, L. , Viitasalo, M. , Toivonen, L. , Kjeldsen, S. E. , Nieminen, M. S. , … Devereux, R. B. (2009). Prognostic value of changes in the electrocardiographic strain pattern during antihypertensive treatment: The Losartan Intervention for End‐Point Reduction in Hypertension Study (LIFE). Circulation, 119(14), 1883–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okin, P. M. , Roman, M. J. , Lee, E. T. , Galloway, J. M. , Howard, B. V. , & Devereux, R. B. (2004). Combined echocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and electrocardiographic ST depression improve prediction of mortality in American Indians: The Strong Heart Study. Hypertension, 43(4), 769–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, S. D. , Macfarlane, P. W. , McKillop, J. H. , Lorimer, A. R. , & Dunn, F. G. (1989). Pathophysiologic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy and strain in asymptomatic patients with essential hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 13(6), 1377–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rembert, J. C. , Kleinman, L. H. , Fedor, J. M. , Wechsler, A. S. , & Greenfield, J. C. (1978). Myocardial blood flow distribution in concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2, 379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romhilt, D. W. , & Estes, E. H. (1968). A point‐score system for the ECG diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy. American Heart Journal, 6, 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schocken, D. D. (2014). Electrocardiographic left ventricular strain pattern: Everything old is new again. Journal of Electrocardiology, 47(5), 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A. S. , Chin, C. W. , Vassiliou, V. , Cowell, S. J. , Doris, M. , Kwok, T. C. … Mills, N. L. (2014). Left ventricular hypertrophy with strain and aortic stenosis. Circulation, 130(18), 1607–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolow, M. , & Lyon, T. P. (1949). The ventricular complex in right ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. American Heart Journal, 38, 273–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus, S. M. , Kors, J. A. , De Bruin, M. L. , van der Hooft, C. S. , Hofman, A. , Heeringa, J. , … Witteman, J. C. (2006). Prolonged QTc interval and risk of sudden cardiac death in a population of older adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 47, 362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorescu, C. , Reinier, K. , Uy‐Evanado, A. , Navarro, J. , Mariani, R. , Gunson, K. , … Chugh, S. S. (2001). Prolonged QRS duration on the resting ECG is associated with sudden death risk in coronary disease, independent of prolonged ventricular repolarization. Heart Rhythm: The Official Journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, 8, 1562–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tereshchenko, L. G. , Henrikson, C. A. , Sotoodehnia, N. , Arking, D. E. , Agarwal, S. K. , Siscovick, D. S. , … Soliman, E. Z. (2014). Electrocardiographic deep terminal negativity of the P wave in V(1) and risk of sudden cardiac death: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Journal of the American Heart Association, 6, e001387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdecchia, P. , Schillaci, G. , Borgioni, C. , Ciucci, A. , Gattobigio, R. , Zampi, I. , Porcellati, C. (1998). Prognostic value of a new electrocardiographic method for diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 31(2), 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]