Abstract

Starch polymer matrices were developed with the incorporation of 1% clove essential oil (EO) (Syzygium aromaticum) aiming for use as active packaging for sausages. At the concentration of 1% EO in the polymer matrix, it showed exponential behavior with respect to oil release over 30 days, with faster release in the beginning and a tendency towards a reduction in release velocity over time. The presence of OE in the biofilm led to significant differences versus the control in terms of aroma and flavor parameters. It was found that EO had an antioxidant effect in sausages with a significant difference between treatments with respect to TBA (thiobarbituric acid) values at the end of a 15 day period of refrigerated storage. There were no significant variations in pH and Aw among treatments during the evaluated period. A significant negative correlation (−0.78) between brightness (L*) and the lipid oxidation of the products was observed.

Keywords: Essential oil, Package, Starch, Antioxidant, Sausage, Release kinetic

Introduction

Environmental pollution due to the disposal of plastic film made of synthetic polymers without any control is a worldwide problem. Due to its abundance and degradability, many researchers have used starch for the production of biodegradable films. Films developed from starch are described as isotropic, odorless, tasteless, colorless, non-toxic and biodegradable (Souza et al. 2010).

According to Souza et al. (2013), packaging needs to be able to not only to protect, but to interact with the product. Active packaging has been developed to interact desirably with the product, changing the storage conditions to increase the shelf life and improve safety and/or sensory properties. Films with additives that are in contact with the surface of the product release the additive in a controlled manner directly to the surface of the product, where the majority of chemical and microbiological reactions occur (Soares et al. 2006).

The release of essential oils (EOs) from the polymeric film to the food is a complex process, affected mainly by the properties of the polymer matrix, the nature of the antioxidant, and the characteristics of the food product. This release it has been studied by different researcher groups. López-de-Dicastillo et al. (2012) produced active packaging films by ethylene vinyl alcohol incorporated of ascorbic acid, ferulic acid, quercetin and green tea extract and the release into the different food simulants was analysed by UV-spectroscopy. Ashwar et al. (2015) produced a rice starch active packaging films loaded with ascorbic acid and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and the release was measured with DPPH test.

To our knowledge the kinetic release of the clove essential oil added into starch film measured by chromatography in one hand, and in the other hand, the application of the active packaging embedded with clove essential oil on sausages and their antioxidant and sensorial alterations in the product have not been investigated. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop cornstarch-based biopolymer films incorporated with commercial clove EO (Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merrill and Perry), to quantify EO incorporation and release over time, and to determine the antioxidant activity and sensory acceptance when the film was used for packaging sausages.

Material and methods

Clove essential oil (Syzygium aromaticum) was purchased from Ferquima. According to technical specifications, the OE had a straw yellow to brown color, density from 1.038 to 1.060 (20 °C), refractive index from 1.527 to 1.540 (20 °C), eugenol content above 85%, with a typical odor and free of impurities.

Development of biopolymer films

The films were prepared from a solution containing 3% cornstarch (w/v), 30% glycerol (w/w) (Proton Química®) as a plasticizing agent, suspended in distilled water and made by the casting method. After this process, the films were stored in sealed recipients at 4 °C until further analysis. Thickness and moiusture content of the films were measured in triplicate analysis.

Quantification of EO

For the quantification of EO effectively incorporated into the polymer matrix, 10 g of biopolymeric film were diluted in 40 mL of water at 4 °C under stirring for 24 h and extracted with hexane for quantification by gas chromatography. The quantification of EO impregnated in the film was performed by comparing the peak area of the major component eugenol with the eugenol area of a standard curve obtained with different EO concentrations.

The chromatographic analysis was performed with an INOWAX fused silica capillary column (30 m × 250 µm id), film thickness of 0.25 µm, an FID detector, and the following temperature program: 40–180 °C (3 °C/min), 180–230 °C (20 °C/min), 230 °C (20 min), injector temperature 250 °C, detector 275 °C, split injection mode, split ratio 1:100, carrier gas H2 (56 kPa), injected volume of diluted sample 1.0 µL in n-hexane (1:10).

To determine the experimental release curve of EO in relation to time, concentrations were evaluated at 0, 1, 7, 15, 21 and 30 days after the biofilms were formulated with 1% clove EO. For this, 10 g of biofilm was interleaved in filter paper and kept moist (0.3 mL of water/g of filter paper) at 4 °C in triplicate, aiming to simulate the gradual release of EO from the biopolymeric film to the product. To describe the behavior of EO release it was employed an empirical kinetic model proposed by Sánchez-Gonzalez et al. (2011). The general expression of the model is presented in Eq. 1:

| 1 |

The constant kinetic k was determined by nonlinear regression of the experimental data employing the software Statistica 8.0® through the Gauss–Newton method with the least square function of data minimization. In the empirical model of the Eq. (1), C 0 is the concentration of clove oil into the biofilm at initial time and, C t is the concentration of clove oil into biofilm at a time t.

Application of biopolymer films as sausage packaging

Forty sausages bought locally were individually packaged with the control biofilm (without EO) or the active biofilm (1% clove EO) and stored under refrigeration at 2.0 ± 2 °C until subsequent analysis.

The sausages were evaluated during their shelf life with respect to lipid oxidation, sensory characteristics, pH, water activity and colorimetric parameters (L*, a*, b*). To set this period, we took into account the validity stipulated by the industry after opening the package by the consumer, which is 8 days.

On the fifth day after the packaging of sausages, the acceptability of products was evaluated (Ethics Assessment no 1392312.1.0000.5351). The evaluations were conducted with forty people, both sexes and untrained, assessed in one session, who were invited to perform the sensory testing, i.e. to differentiate from the control sample in terms of color, taste and aroma (0 = no difference, 8 = extremely different) (Minim 2006).

Lipid oxidation was evaluated to quantify thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), according to the methodology described by Papastergiadis et al. (2012) at predetermined time intervals during the shelf life of the products.

The pH of the products was determined according to Dias et al. (2013). The water activity (Aw) was obtained using Aqualab® equipment and color parameters (L*, a* and b*) were measured using a Minolta® colorimeter calibrated with white standard plate (L* = 93.00, a* = 0.3136, b* = 0.3321), aperture of 8 mm, illuminant D65, and 10° standard observer were used at the beginning and end of the experiments.

The control sample was maintained with no application of biofilm, and was subjected to the same analysis as the other treatments.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in triplicate, and the results were submitted to ANOVA with Tukey’s test (P < 0.05) using Statistica® 8.0. Data of acceptability of products were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) and with the Dunnet test at 5% probability. The Pearson correlation between brightness and the lipid oxidation was performed with Microsoft Office Excel 2007.

Results and discussion

Quantification of EO

The starch films with 1% of EO presented 0.105 ± 0.01 mm of thickness and 7.21 ± 0.15% of moisture content. Similar results were obtained by Ashwar et al. (2015). The highest concentrations of EO could not be fully incorporated into the polymer film in pre-tests. The mechanical properties were not evaluated.

The oil release kinetics was investigated in a system to simulate interaction with a meat product, resulting in a final release of around 68% of the incorporated oil in 30 days. The experimental data on the release kinetics of clove EO are presented in Table 1 and the correlation obtained by the empirical model, presented a value of −0.1267 for the kinetic parameter k, obtained from nonlinear regression of the experimental data. The model has a good representation capability of the release kinetics of clove EO in the range of experimental conditions studied, with a correlation coefficient, R2 of 0,9016.

Table 1.

Experimental mean results of concentration (Ct) and percentage of clove oil remained into polymeric biofilm in different times with an initial concentration of clove oil into biofilm of 1 wt%

| Time (days) | Ct (mg EO/g biopolymeric film) | Clove EO into biofilm (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.676 ± 0.037 | 100.0 ± 5.5 |

| 1 | 0.472 ± 0.067 | 69.8 ± 14.2 |

| 7 | 0.434 ± 0.042 | 56.6 ± 9.7 |

| 15 | 0.365 ± 0.035 | 54.0 ± 9.6 |

| 21 | 0.290 ± 0.036 | 42,9 ± 12.4 |

| 30 | 0.216 ± 0.033 | 31.9 ± 15.3 |

The EO release curve presents a behavior that confirms the results reported in the literature about EO release and other active components released from polymeric matrices (Beirão-da-Costa et al. 2013).

According to the literature, the release of EO from the polymeric matrix occurred in two different phases. In the first phase, there was rapid release of EO (burst effect) due to volumetric expansion of the polymer with the diffusion of solvent molecules into the polymeric network when it came into contact with an aqueous medium, causing hydration of the polymer (Beirão-da-Costa et al. 2013). In the present study, it is believed that this effect was primarily responsible for the rapid initial release of the EO (~30% in the first 24 h) through the polymer film and into the aqueous medium. In the second phase, a number of effects made the release practically zero. The main effect was the increasing path of essential oil diffusion within the polymeric biofilm to the external aqueous medium associated with the physical and chemical interactions of EO with the structure of the polymer matrix. Thus, the release of the essential oil in this step (for a longer period) happened slowly and steadily (Beirão-da-Costa et al. 2013).

Product evaluation

Sensory evaluation

Regarding the color, there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the treatments (sausages packaged with starch and packaged with starch + 1% clove EO) and control (sausages not packaged). The treatment (starch + 1% clove EO) was statistically different (P < 0.05) relative to control, regarding the flavor and aroma parameters.

Although various EO have antimicrobial and antioxidant activities (Hyldgaard et al. 2012), one of the major limitations to EO use as preservatives in food is the negative effect on the sensory quality of the product. Since in the present study the oil was not incorporated directly into the food, but rather in the biofilm, it was expected that this effect would not be significant.

Lipid oxidation

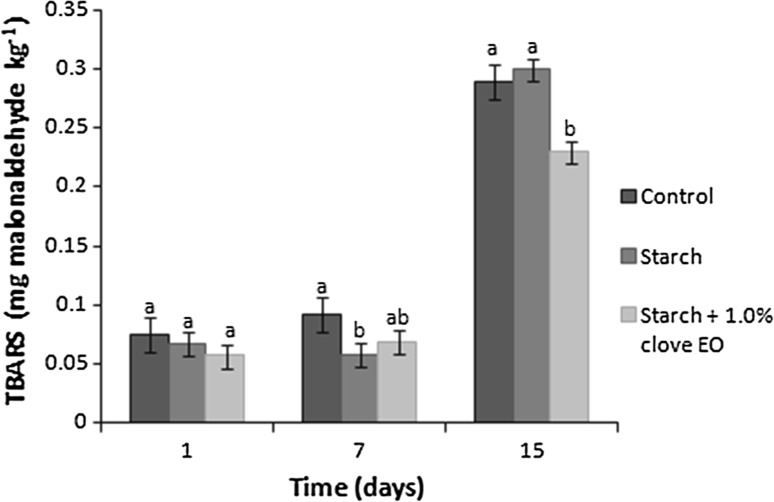

The mean values of TBA generated during the refrigerated storage of sausages are shown in Fig. 1. On the first and 7th storage days, TBA values ranging between 0.057 and 0.092 mg malonaldehyde.kg−1. On the 15th day of storage, sausage samples packaged with biofilm containing starch plus 1% EO differed significantly (P < 0.05) from control samples and sausages packaged only with starch biofilm. According to Gadekar et al. (2008), the acceptable limit of lipid oxidation is 1 mg of malonaldehyde.kg−1, a value that was not achieved by any of the samples during the storage period.

Fig. 1.

Mean TBARS index (mg malonaldehyde.kg−1) of sausage samples during storage at refrigeration temperature (5 °C). Means with different letters on the same day are significantly different by Tukey’s test (P < 0.05)

In the present study, it was found the antioxidant action of clove EO, released from the biopolymeric film to the product in 15 days of storage, was in agreement with the in vitro release assay, wherein 15 days 53% release of the EO initially retained in the starch film was observed (Table 1).

We have not found studies in the literature on antioxidant activity in sausages packed with starch film embedded with clove essential oil. However, our results are in agreement with various other studies in films, all of which reported that natural antioxidants from culinary herbs and edible plants were effective at controlling lipid oxidation and extending the shelf life of meat products. Active films with oregano essential oil (2%) resulted in a decreased lipid oxidation of foal steaks, and these were more efficient than those treated with green tea (1%) (Lorenzo et al. 2014). Inactivation of free radicals by either migration of antioxidant molecules from the active film to the meat or scavenging of those oxidant molecules from the meat into the active film may be considered as hypotheses for its mechanism of action (Gallego et al. 2016). Acín (2011) evaluated the release kinetics of the compounds eugenol and carvacrol (1%) from a film produced with isolated whey proteins in three food simulants, olive oil, water and an aqueous ethanol solution 10% (v/v). The diffusion of the active compound was faster in polar simulators, reaching to 90% after 2 h of contact, than in non-polar olive oil, at 32%.

In the exposure of active antioxidant films to various food simulators, it was evident that the release of the active substances was dependent on the environment and type of antioxidant. The migration of an antioxidant from a polymer film to food is a complex process that is primarily affected by the properties of the polymer matrix, the nature of the antioxidant substance, including polarity, solubility, functional groups and hydrophobicity and the characteristics of the product surface (López-de-Dicastillo et al. 2012; Tehrany and Desobry 2007).

pH

There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the different treatments during the refrigerated storage of products, with pH values between 5.97 and 6.07. Ferraccioli (2012) report a downward trend in pH values in sausages during storage, probably due to the development of lactic acid bacteria, an important deteriorative group of microorganisms in cooked sausages. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas (Enterobacteriaceae) as well as molds and yeasts degrade proteins and amino acids, resulting in the formation of ammonia with a consequent increase in pH (Nychas et al. 1998).

Water activity (Aw)

On the first day, there was a significant difference (P > 0.05) in the control and starch film treated samples (0.98) compared to treatment with 1% EO (0.97). On the last day of analysis (15 days), there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the treatments, where all treatments showed water activity of 0.97 ± 0.001. Most microorganisms, including pathogenic bacteria, grow in an Aw range between 0.98 and 0.99, indicating the importance of additional preventive measures being adopted to ensure the microbiological safety of products such as sausages.

Colorimetric parameters (L*, a* and b*)

Color attributes are of primary importance, because they directly influence the acceptance of the product by the consumer. The L* attribute (brightness) underwent significant alterations (P < 0.05), with reduced brightness after 15 days of storage for the control treatment compared to the treatment with EO (Table 2). Was observed significantly negative correlation between brightness and the lipid oxidation of the products (−0.78 Pearson correlation). Changes in the brightness of meat products may be linked to lipid oxidation products, since during storage peroxide or its degradation products may interact with proteins and amino acids and form dark pigments (Araújo 2011).

Table 2.

Mean values of chroma L*, a* and b* in sausage samples stored at refrigeration temperature (5 °C)

| Parameter | Time (days) | Control | Starch | Starch plus 1% of clove EO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 1 | 41.65 ± 1.62a | 42.73 ± 1.99a | 43.55 ± 1.89a |

| 15 | 40.24 ± 1.48b | 42.19 ± 1.33ab | 43.97 ± 0.71a | |

| a* | 1 | 18.89 ± 1.69b | 23.41 ± 1.64a | 20.39 ± 1.36ab |

| 15 | 19.82 ± 0.70ab | 20.49 ± 1.01a | 17.43 ± 2.19b | |

| b* | 1 | 11.58 ± 1.04b | 14.53 ± 1.17a | 12.80 ± 0.76ab |

| 15 | 12.94 ± 0.57a | 12.76 ± 0.64a | 9.86 ± 1.80b |

* Means with different letters on the same day of analyzes are significantly different (P < 0.05) by Tukey´s test

The chroma a* showed positive values in all samples, indicating the presence of a red color. On first day, values were between 18.89 and 23.41, and the highest averages were observed in the samples packaged with the starch biofilm. On the 15th day of analysis, the values were between 17.43 and 20.49, with no significant difference (P < 0.05) between the sausages packaged with starch + 1% clove EO and control sausages.

The values of chrome b* were between 11.58 and 14.53 on the first day, with the highest average observed in sausages packaged with the starch biofilm. After 15 days of refrigerated storage, the averages were between 9.86 and 12.94, and only the sausages packaged with starch + 1% clove OE differed significantly from the others (P < 0.05).

Future research could be conducted to characterize their stability and other physico-mechanical properties. Even so, these active films appear promising for the development of active antioxidant packaging for use on sausages.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank CNPq, CAPES, FAPERGS and URI-Erechim for the financial support for this research.

References

- Acín JMO (2011) Estudio de la difusión del carvacrol y el eugenol desde películas de proteína de suerolácteo a diferentes simulantes alimentarios. Máster. Departamento de Tecnología de los Alimentos, Universidad Pública de Navarra, p 65

- Araújo JMA (2011) Química de Alimentos -Teoria e Prática. Viçosa: Ed. UFV, p 478

- Ashwar BA, Shah A, Gani A, Shah U, Gani A, Wani IA, Wani SM, Masoodi FA. Rice starch active packaging films loaded with antioxidants-development and characterization. Starch/Stärke. 2015;67:294–302. doi: 10.1002/star.201400193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beirão-da-Costa S, Duarte C, Bourbon AI, Pinheiro AC, Januário MIM, Vicente AA, Beirão-da-Costa ML, Delgadillo I. Inulin potential for encapsulation and controlled delivery of Oregano essential oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;33:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dias FS, Ramos CL, Schwan RF. Characterization of spoilage bacteria in pork sausage by PCR–DGGE analysis. Food Sci Technol. 2013;33:468–474. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraccioli VR (2012) Avaliação da qualidade de salsichas do tipo hot dog durante o armazenamento. Dissertação, Escola de Engenharia Mauá do Centro Universitário do Instituto Mauá de Tecnologia, São Caetano do Sul, p 116

- Gadekar YP, Anjaneyulu ASR, Kandeepan G, Mendiratta SK, Kondaiah N. Safe pickle with improved sensory traits: effect of sodium ascorbate on quality of shelf stable pickled cooked chicken. Fleischwirtsch Int. 2008;4:56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego MG, Gordon MH, Segovia F, Pablos MPA. Gelatine-based antioxidant packaging containing Caesalpinia decapetala and tara as a coating for fround beef patties. Antioxidants. 2016;5:1–15. doi: 10.3390/antiox5020010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyldgaard M, Mygind T, Meyer RL. Essential oils in food preservation: mode of action, synergies, and interactions with food matrix components. Front Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-de-Dicastillo C, Gómez-Estaca J, Catalá R, Gavara R, Hernández-Muñoz P. Active antioxidant packaging films: development and effect on lipid stability of brined sardines. Food Chem. 2012;131:1376–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo JM, Batlle R, Gómez M. Extension of the shelf-life of foal meat with two antioxidant active packaging systems. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2014;59:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.04.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minim VPR. Análise sensorial–estudos com consumidores. Viçosa: Editora UFV; 2006. p. 225p. [Google Scholar]

- Nychas GJE, Drosinos EH, Board RG. Chemical changes in stored meat. In: Board RG, Davies AR, editors. The Microbiology of meat and poultry. London: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1998. pp. 288–326. [Google Scholar]

- Papastergiadis A, Mubiru E, Van Langenhove H, Meulenaer B. Malondialdehyde measurement in oxidized foods: evaluation of the spectrophotometric thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) test in various foods. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9589–9594. doi: 10.1021/jf302451c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gonzalez L, Cháfer M, González-Martínez C, Chiralt A. Study of the release of limonene present in chitosan films enriched with bergamot oil in food stimulants. J Food Eng. 2011;105:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soares NFF, Pires ACS, Endo É, Vilela MAP, Silva AF, Fontes EAF, Melo NR. Desenvolvimento e avaliação de filme ativo na conservação de batata minimamente processada. Rev Ceres. 2006;53:387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Souza AC, Ditchfield C, Tadini CC. Biodegradable films based on biopolymers for food industries. In: Passos ML, Ribeiro CP, editors. Innovation in food engineering: New techniques and products. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2010. pp. 511–537. [Google Scholar]

- Souza AC, Goto GEO, Mainardi JA, Coelho ACV, Tadini CC. Cassava starch composite films incorporated with cinnamon essential oil: antimicrobial activity, microstructure, mechanical and barrier properties. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2013;54:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrany EA, Desobry S. Partition coefficient of migrants in food simulants/polymers systems. Food Chem. 2007;101:1714–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.03.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]