Abstract

Purple coloured tea shoot clones have gained interest due to high content of anthocyanins in addition to catechins. Transcript expression of genes encoding anthocyanidin reductase (ANR), dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), flavonol synthase (FLS) and leucoantho cyanidin reductase (LAR) enzymes in three new purple shoot tea clones compared with normal tea clone showed higher expression of CsDFR, CsANR, CsANS and lower expression of CsFLS and CsLAR in purple shoot clones compared to normal clone. Expression pattern supported high content of anthocyanins in purple tea. Four anthocyanins (AN1–4) were isolated and characterized by UPLC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS from IHBT 269 clone which recorded highest total anthocyanins content. Cyanidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside (AN2) showed highest in vitro antioxidant activity (IC50 DPPH = 25.27 ± 0.02 μg/mL and IC50 ABTS = 10.71 ± 0.01 μg/mL). Anticancer and immunostimulatory activities of cyanidin-3-glucoside (AN1), cyanidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside (AN2), delphinidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside (AN3), cyanidin-3-O-(2-O-β-xylopyranosyl-6-O-acetyl)-β-glucopyranoside (AN4) and crude anthocyanin extract (AN5) showed high therapeutic perspective. Anthocyanins AN1–4 and crude extract AN5 showed cytotoxicity on C-6 cancer cells and high relative fluorescence units (RFU) at 200 μg/mL suggesting promising apoptosis induction activity as well as influential immunostimulatory potential. Observations demonstrate potential of purple anthocyanins enriched tea clone for exploitation as a nutraceutical product.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13197-017-2631-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tea, Anthocyanins, Antioxidant activity, Cytotoxicity, Immunostimulatory activity

Introduction

Flavonoids, the secondary plant metabolites having antioxidant activity, are important dietary sources. Anthocyanins are a major sub-group of the flavonoids, which includes glycosylated anthocyanidins. These exhibit antioxidant activities and impart red, purple and blue colour to leaves, flowers, fruits and vegetables (Tsuda 2012). In plants, anthocyanins provide protection from prolonged UV-B exposure and protection against invasion from pests and herbivores. In addition, these are reported potential dietary components for nutritional and management of several health disorders (Zafra-Stone et al. 2007).

The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway has been almost completely elucidated in various plant species including tobacco, Arabidopsis thaliana, Medicago truncatula and Camellia sinensis (Wu et al. 2014). The phenylalanine and malonyl-CoA are precursors for flavonoid biosynthetic pathways. The chalcone synthase (CHS) enzyme condenses these precursors to form intermediate chalcone that undergoes a series of reactions by a number of enzymes including flavanone-3-hydroxylase (F3H), dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (DFR) and leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (LDOX) to produce anthocyanidins. Anthocyanins, the end product of biosynthetic pathway is synthesized by conjugation of sugars with anthocynidins by enzymatic action of UDP-glucose/flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT) and O-methyltransferase (OMT) enzymes (Kassim et al. 2009; Fig. S1). Another end products of flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in plants are catechins.

Recently, Saito et al. (2011) reported six novel anthocyanins from red leaves of Sunrouge cultivar, a purple shoot tea clone. Akiyama et al. (2012) have reported the inhibitory effects of extracts of anthocyanin rich Sunrouge tea on colitis in dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-treated mice. Purple coloured tea shoots were also evaluated for their anti-proliferative effects on colorectal carcinoma cells and found to be involved in the cleavage of PARP activation of caspase-3 (Chih-Ping et al. 2012). Anti-proliferation and radiation-sensitizing effects were also observed against colon cancer cells in anthocyanidin-rich extract obtained from purple-shoot tea (Lin et al. 2012). Similarly, antioxidant activity has also been documented in purple tea shoots from Kangra and Zijun province of India and China, respectively (Joshi et al. 2015; Jiang et al. 2013).

To understand why some tea clones have stable purple coloured shoots despite normal green coloured shoots, the gene expression analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway encoding enzymes LAR, CHS, F3H, DFR and ANS in both normal and purple coloured tea shoots was studied. Anthocyanins were also extracted and purified from purple tea shoot clones and characterized by UPLC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS. Purified anthocyanins were assigned as AN1, AN2, AN3 and AN4 while AN5 for crude anthocyanins extract studied for antioxidant, anticancer, apoptotic and immunostimulatory activities.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, solvents, cell, media

l-Ascorbic acid, Trolox® (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetrametyl chroman-2-carboxylic acid), 2,2′-azinobis-(3 ethylbenzothiazonline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS+), XAD-16 and C-18 packing were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore (India). Ethanol (EtOH), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), methanol (MeOH) and acetonitrile (ACN) were HPLC grade purchased from Merck Specialties, Mumbai, India.

Plant material

Fresh tea shoots (apical bud and subtending two leaves) were collected during the month of May from Experimental Tea Farm of CSIR-IHBT situated at Banuri (36°N and 78.18°E, 1200 m above mean sea level), Palampur, India. The purple coloured tea shoot clones used in this study are IHBT-269 (PLI), IHBT-270 (PLII) and IHBT-271 (PLIII). Clone IHBT-002 (GL) was used as a reference standard normal high quality green shoot tea clone.

Determination of total catechins and anthocyanin content in purple tea leaves

Tea shoot samples were dried to constant weight and extracted following the method reported by Joshi et al. (2015). Total catechins and anthocyanins content in purple tea leaves were determined according to pH differential as reported in Joshi et al. (2015).

Gene expression analysis by semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Comparative semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed to examine the expression levels of anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes in fresh green (GL) and purple leaves of different shoot clones (PLI, PLII, PLIII) of tea. Leaves were collected between 09:00 and 10:00 a.m. during the period of active growth (in the month of May with mean temperature 23.5 ± 1 °C), and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C till further use. Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of leaf tissue using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). To avoid DNA contamination, total RNA from each sample was treated with DNase I. First strand cDNA was prepared from 1 µg of total RNA using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase according to manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, USA). Equal quantity of cDNA was used as template in PCR with gene-specific primer sets to check the expression of selected anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes. Linearity between amount of RNA added and the final PCR products were verified and confirmed. After standardizing the optimal amplification at exponential phase, the final PCR amplification of Camillia sinensis dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (CsDFR), flavonol synthase (CsFLS), leucoanthocyanidin reductase (CsLAR), anthocyanidin reductase (CsANR) and anthocyanidin synthase (CsANS) genes were carried out. The various primer sequences used in this study are CsDFR: (R-CCACCCCACCATACAAAAAC); (F-GCTGACACGAACTTGACAC); CsFLS: (R-TATTCCTCTGTCACTCCCCTGT); (F-CTAAAAGAGGTTGGGGAGGAGT); CsLAR: (R-CTATCTCTGCCTACCTTTGTGA); (F-ATCGTTCACACACGACATTTTC); CsANR: (R-TAGCTTTTGTGATCGACTCTTT); (F-ATGATAAAACCAGCAATTCAAG) and CsANS: (R-AACTTCGGGTGTGACTGAAC); (F-TCGAGCCCTAGCTACCAAGA). The thermo cycling procedure involved an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min, followed by 28 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 52 °C (CsANS gene), 54 °C (CsANR gene) and 58 °C for (CsDFR, CsFLS and CsLAR genes) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The amplified products were separated on 1% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. The 26S rRNA-based gene primers were used as internal control for gene expression studies. A gel documentation system (Alpha DigiDoc™, Alpha Innotech, USA) was used to scan the gels while changes in the gene expression were analyzed by calculating integrated density values (IDV) using AD-1000 software.

Extraction and purification of anthocyanins from purple tea shoots

Fresh purple tea shoots (500 g) were plucked from shoot clones IHBT-269 and immediately homogenized in a laboratory homogenizer using 0.4% TFA in 60% EtOH (1000 mL × 3). Obtained extracts were filtered using Buchner funnel, pooled and evaporated under reduced pressure to dryness in a Buchi rotary evaporator. Residue obtained was re-dissolved in water (WE) and loaded on a column packed with XAD-16 resin. Prior to sample application, the resin was conditioned with 1000 mL water (pH 2, acidified with 0.1% TFA) to remove sugars and salts. The adsorbed anthocyanins were eluted from the column applying 90% methanol. Eluted extract was lyophilized using lyophilizer (Labconco, USA) to get powdered AN5 as a mixture of anthocyanins. For further purification of individual anthocyanins, lyophilized AN5 (5 g) was dissolved in deionized water (containing 0.4% TFA) and purified on a C-18 silica column. After conditioning the C-18 column with deionized water (acidified with 0.4% TFA), the column was eluted with 0.4% TFA in ACN/water using gradient elution from 10 (0.4% TFA in ACN) to 50% (0.4% TFA in ACN). Eluents from the column were collected starting from 10 (0.4% TFA in ACN) to 50% (0.4% TFA in ACN) to get ten fractions (15 mL each). All fractions were dried on a rotor evaporator and lyophilized as Fr. 1 (1.50 g), Fr. 2 (0.80 g), Fr. 3 (0.18 g), Fr. 4 (0.28 g), Fr. 5 (0.59 g), Fr. 6 (0.31 g), Fr. 7 (0.28 g), Fr. 8 (0.16 g), Fr. 9 (0.12 g) and Fr. 10 (0.14 g). Fraction 5 was further purified by loading on to another C-18 column to yield two purple amorphous pigments: AN1 and AN2 weighing 28 and 30 mg, respectively. Fraction 7 was also further subjected to C-18 column chromatography to furnish two reddish amorphous fractions AN3 and AN4 weighing 38 and 42 mg, respectively by changing the solvent polarity. Purified anthocyanins (AN1–4) were run on thin layer chromatography plate of microcrystalline cellulose F (Merck) with n-BuOH:AcOH:H2O (4:1:5, taking upper layer) for identification. Acid hydrolysis was carried out to determine the sugars in anthocyanins as explained in Joshi et al. (2012). The hydrolyzed mixture was compared on TLC with standard sugars. For distinguishing sugars; BAW (n-BuOH:AcOH:H2O::4:1:2) was used as the solvent system while detection was performed by spraying with 5% H2SO4, followed by heating.

UPLC and UPLC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS characterization

For UPLC and UPLC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS analyses, samples were prepared in a mixture of ACN/water (80:20; v/v) and filtered through a 0.22 μm Millex GV syringe filter prior to injection on to UPLC system. Waters Acquity UPLC System (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used for identification and characterization of anthocyanins. Separation was achieved on an Acquity UPLC® BEH C18 column (100 mm, 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 μm particle size) maintained at 30 °C, with solvent flow rate of 0.40 mL/min. The mobile phase comprised of 0.04% TFA in water (A) and 0.04% TFA in ACN (B). Gradient elution was employed starting at 12% B shifting linearly to 15% over 0.82 min, then to 22% over 2.72 min, 30% over 4.8 min and back to 12% at 5.44 min with 1.0 min re-equilibration time, giving a total cycle time of 7.0 min. The injection volume was 2 μL with partial loop injection using needle overfill mode. AN1–4 and AN5 were monitored at 520 nm (Fig. S2). A time-of-flight mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization (ToF-ESI-MS) interface was used for anthocyanin fingerprinting (Micromass, Manchester, UK). For UPLC analysis, data acquisition was performed using positive ion mode over a mass range of m/z 100–1000. The general conditions were: source temperature 80 °C, capillary voltage of 2.1 kV and cone voltage of 23 V. Negative ion ESI-MS analysis was performed by direct infusion with flow rate of 10 μL/min using a syringe pump. Mass spectra were acquired and accumulated over 60 s, spectra were scanned between 100 and 1000 m/z. MassLynx 4.1 (Waters, Manchester, UK) was used for data analysis. Structural analysis of pure anthocyanins single molecular ion was performed by tandem mass spectrometry. ESI-ToF-MS/MS was performed by selecting the ion of interest, which was in turn submitted to 15–35 eV collisions with argon in the collision quadruple.

Antioxidant activity using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate (DPPH+) and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS+) radical assay

DPPH+ and ABTS+ radical-scavenging activity was performed by following the method of Joshi et al. (2015).

Measurement of TAC against DPPH+ and ABTS+

TAC was measured against both DPPH·+ and ABTS·+ free radical solutions. The total antioxidant capacity (TAC) was estimated for AN1–5 as trolox equivalents (TEAC) interpolation to 50% inhibition (TEAC50).

Cell lines and cell culture

Cell line C-6 (glioma cells) was obtained from Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, India and grown in DMEM (Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum with antibiotic antimycotic (1%). Human lung carcinoma cells (A-549) were obtained from Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, Jammu, India and were grown in HAM’S F-12 medium (Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma Aldrich, India) and 1% antibiotic antimycotic. These cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere (Thermo Scientific, India).

Isolation of lymphocytes

Lymphocytes were isolated from freshly collected peripheral venous human blood drawn in heparinized tubes as described in Joshi et al. (2012).

Sulphorhodamine B (SRB) assay

The level of cytotoxicity was determined using SRB assay as described in Joshi et al. (2012). Vinblastin (1 μM) was used as positive control.

Microscopic characterization of cells

Morphological changes in C-6 cells treated with AN5 and purified anthocyanins: AN1–4 for 24 and 48 h were observed under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti) at 10× magnification (Walia et al. 2012).

Apoptotic assay (caspase-3/7 activity)

Cells were plated in flat bottomed 96-well plates at a density 2 × 103 cells/well in 50 μL of complete medium. Total caspase activity was detected using Apo-ONE homogeneous Caspase-3/7 assay kit (Promega) following the method of Walia et al. (2012).

Lymphocyte proliferation assay

RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 110 mg/mL of sodium pyruvate and 1% antibiotic antimycotic was used in the assay. The assay was performed using 96-well cell culture plates (Corning Costar, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2, for 72 h as explained in Joshi et al. (2012).

UPLC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS and UV–Vis data

AN1: Cyanidin-3-glucoside, ESI-MS m/z 449 [M]+ (calcd. For C21H21O11 + was m/z 449.1213). UV–Vis λmax 0.01% HCl-MeOH (nm): 517. AN2: Cyanidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside, HR-ESI-MS m/z 595 [M]+ (calcd. For C30H27O13 + was m/z 595.14462). UV–Vis λmax 0.01% HCl-MeOH (nm): 522. AN3: Delphinidin-3-O-β-D-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside, HR-ESI-MS m/z 611 [M]+ (calcd. for C30H27O14 + was m/z 611.13953). UV–Vis λmax 0.01% HCl-MeOH (nm): 529. AN4: Cyanidin-3-O-(2-O-β-xylopyranosyl-6-O-acetyl)-β-glucopyranoside, HR-ESI-MS m/z 623 [M]+ (calcd. For HR ESI–MS m/z 623.3868 [M] + (calc. for C28H31O16 623.4412). UV–Vis λmax 0.01% HCl-MeOH (nm): 534.

Principle component analysis (PCA)

PAST software (Ver. 2.17c) was used for principal component analysis to examine the correlation of antioxidant analysis of anthocyanins with anticancer activity to identify the main groups among the anthocyanins.

Data analysis

Results of the parameters determined were expressed as a mean of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

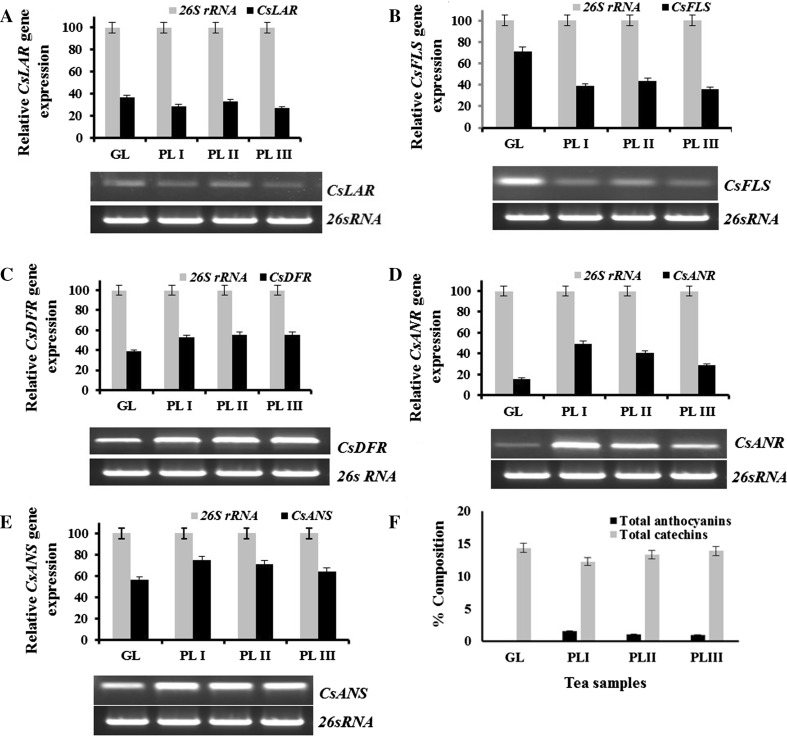

Expression of genes encoding enzymes of anthocyanins biosynthetic pathway

The expression of genes encoding enzymes of anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in green tea shoot clone (GL) and purple tea shoot clones (PL-I–PL-III) was analyzed. The expressions of CsLAR, CsFLS was lower while expression of CsDFR, CsANR, and CsANS was higher in purple tea shoot clones compared to normal green shoot clone (Fig. 1). The relative expression of CsLAR and CsFLS was lower by 7.86, 3.86, 9.57 and 32.41, 27.71, 35.39% in PLI, PLII and PLIII as compared to GL, respectively (Fig. 1a, b). On contrary, the relative expression of CsDFR was higher in purple leaf shoot clones PLI, PLII and PLIII by 14.02, 16.50 and 16.57%, respectively, as compared to green leaf shoot clones GL (Fig. 1c). The relative expression of CsANR and CsANS was also higher by 33.86, 25.08, 12.78 and 18.71, 15.26, 8.27% in PLI, PLII and PLIII compared to GL, respectively (Fig. 1d, e). Total anthocyanin content in purple tea clones was estimated and expressed as cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalent. Anthocyanin content in purple tea leaves of PL I, PL II and PL III was 1.53 ± 0.06, 1.08 ± 0.09 and 0.98 ± 0.05%, respectively (Fig. 1f). Anthocyanins were found to be below the detection limit in GL. Purple tea shoot clone PLI was taken forward for purification of anthocyanins as it recorded highest anthocyanin content among the purple tea shoot clones taken for the study.

Fig. 1.

Expression of a CsLAR, b CsFLS, c CsDFR, d CsANR, e CsANS in normal (GL, IHBT-002) and purple tea (PL1, IHBT-269; PL II, IHBT-270; PLIII, IHBT 271) shoot clones. Expression of 26sRNA served as an internal control. Bar diagram shows relative gene expression of the amplified bands measured with Alpha Digidoc 1000 software. f Total catechins and anthocyanins. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three separate biological replicates. CsDFR Camillia sinensis dihydroflavonol-4-reductase; CsFLS Flavonol synthase; CsLAR Leucoanthocyanidin reductase; CsANR Anthocyanidin reductase and CsANS Anthocyanidin synthase

Purification and characterization of anthocyanins using UPLC-ESI-QToF-MS/MS

Sugars, amino acids and lipids were removed from methanolic extract of PLI using XAD-16 resin column with 0.1% TFA followed by methanol to get enriched anthocyanins extract. Enriched anthocyanins extract was dried on rotor evaporator (40 °C) followed by lyophilization to get AN5 fraction. UPLC analysis of AN5 revealed the presence of several major and minor anthocyanins. The powder was re-dissolved in water and subjected to C-18 silica column chromatography. TFA (0.05%) in ACN was used as mobile phase to separate four coloured anthocyanins AN1–4. Two purple and two reddish amorphous pigments: AN1, AN2, AN3 and AN4 weighing 28, 30, 38 and 42 mg, respectively were isolated. ESI-MS/MS data were collected by monitoring the molecular ion characteristics of four peaks (Fig. S2). The MS/MS analysis of compounds AN1–4 showed molecular ion at m/z 449, 595, 611 and 623, respectively which established the identity of these compounds as cyanidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-p-coumaroyl)-gluco pyranoside, delphinidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside and cyanidin 3-O-(2-O-β-xylopyranosyl-6-O-acetyl)-β-glucopyranoside by comparing their MS data with published data (Saito et al. 2011; Li et al. 2008, 2009) (Fig. S3). Four major anthocyanins isolated were cyanidin-, cyanidin-glucoside, delphinidine- and delphinidine acylated with glucose.

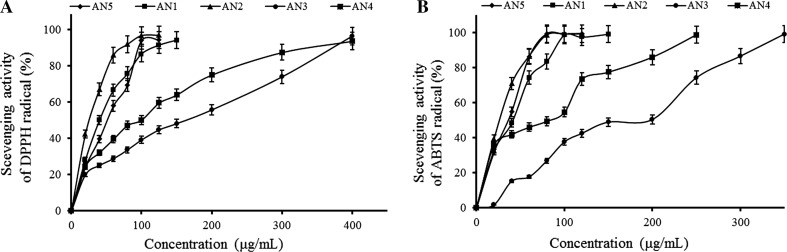

Free radical scavenging potential of isolated anthocyanins using DPPH+ and ABTS+ radical-scavenging assays

Free radical potential of AN5 and AN1–4 was assessed by DPPH and ABTS assays. Concentration-dependent curves of DPPH+ radical scavenging activity of AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins were illustrated in Fig. 2a. The radical scavenging activity of AN1–4 and AN5 were expressed as IC50 value (μg/mL) compared with standard (Table 1). The DPPH and ABTS IC50 values of crude extract AN5 and purified anthocyanins AN1 to AN4 ranged from 25.27 to 166.47 and 10.71 to 144.21 μg/mL, respectively. Purified AN2 showed lowest IC50 values for DPPH+ (25.27 μg/mL) and ABTS+ (10.71 μg/mL) among the different anthocyanins tested to possess highest antioxidant activity. Both DPPH+ radical scavenging activity and ABTS+ radical scavenging activity of AN1–4 and AN5 showed increase in radical scavenging activity with concentration (Fig. 2b). Tea catechins contribute to its high antioxidant activity and free radicals scavenging activity by forming a stable complex ABTS-H with ABTS+ (Osman et al. 2009). IC50 values of different anthocyanins for ABTS assay varied in accordance with DPPH, ranging from 10.71 to 144.21 μg/mL, however, AN3 showed higher antioxidant potential compared to the other anthocyanins tested. AN1–4 and AN5 at a concentration of 100 μg/mL were chosen to test the correlation between the two radical scavenging assays viz. DPPH+ and ABTS+ (Table 1). Statistically significant correlation (R 2 = 0.989) was observed between data obtained by DPPH+ versus ABTS+ assay. The percent antioxidant activity of AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins lied between 39.22–96.82 and 37.64–99.32% for DPPH+ and ABTS+ assays, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Scavenging effect on a DPPH and b ABTS+ radical of samples and each value is expressed as a mean ± SD

Table 1.

Antioxidant activity (IC50 and % inhibition) of purified (AN1–4) and crude extract (AN5) using DPPH and ABTS assays

| Samples | IC50 (μg/mL) | (% Inhibition) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | ABTS | DPPH | ABTS | |

| AN1 | 40.44 ± 0.04 | 32.22 ± 0.03 | 86.60b | 98.65c |

| AN2 | 25.27 ± 0.02 | 10.71 ± 0.01 | 96.82 | 99.32 |

| AN3 | 166.47 ± 0.12 | 144.21 ± 0.16 | 39.22 | 37.64 |

| AN4 | 108.30 ± 0.10 | 68.64 ± 0.11 | 50.27 | 54.62 |

| Crude extract (AN5) | 52.36 ± 0.03 | 27.76 ± 0.02 | 94.06 | 99.32 |

| Catechin extract of green tea | 58.05 ± 0.02 | 35.15 ± 0.03 | ||

| Ascorbic acid | 1.74 ± 0.03 | 1.09 ± 0.04 | ||

| Trolox | 2.66 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.01 | ||

DPPH = 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate; ABTS = 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)

aResults were expressed as the averages of triplicates (mean ± SD)

b,cInhibition at concentration 100 μg/mL

Anticancer activity of anthocyanins

The effects of AN5 and purified anthocyanins AN1–4 were tested against C-6 and A549 cells in vitro at various concentrations (50–200 µg/mL) by SRB assay method. The percentage viable cell was calculated by measuring the absorbance of respective incubated cells. The anthocyanins showed concentration dependent cytotoxicity against C-6 cell line. AN1–4 and AN5 showed cytotoxic effect of 55.9, 58.1, 63.9, 46.9 and 57.4% respectively on C-6 cells at a concentration of 200 μg/mL (Fig. 3A, B), however, AN3 did not show any cytotoxic effect on C-6 cell line. Morphological changes were also observed in C-6 cells treated with AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins. Reduction in cell count was observed with increase in the concentration of compounds all anthocyanins. The affected cells showed some features of apoptosis such as cellular shrinkage, membrane blabbing, nuclear compaction and fragmentation and formation of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 3A). AN1–3 and AN5 showed higher cytotoxic activity (21, 21.3 21.8 and 15%, respectively) measured as cell death at concentration of 150 μg/mL whereas AN4 showed lowest cytotoxicity (14.9%) at concentration of 200 μg/mL against A549 cells (Fig. 3C). It is, thus, evident from data that the effect of these crude and purified anthocyanins was not lethal for A549 cell line.

Fig. 3.

A Microscopic images for cytotoxicity evaluation of C-6 cells treated with anthocyanins. a C-6 cells without any treatment after 24 h. b C-6 cells without any treatment after 48 h. c C-6 cells after 24 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN1. d C-6 cells after 48 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN1. e C-6 cells after 24 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN2. f C-6 cells after 48 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN2. g C-6 cells after 24 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN3. h C-6 cells after 48 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN3. i C-6 cells after 24 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN4. j C-6 cells after 48 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN4. k C-6 cells after 24 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN5. l C-6 cells after 48 h of addition with 200 µg/mL of AN5; In vitro cytotoxicity of anthocyanins against B C-6 and C A549 cells by SRB assay

Apoptotic activity of anthocyanins

The mechanism of inhibition of anthocyanins was also studied by apoptotic assay against C-6 cells using varying sample concentrations (50–200 μg/mL). Activity of Caspase-3/7 was calculated by measuring relative fluorescence units (RFU) of respective incubated cells in 96 well plates (Fig. 4a). AN1–2 and AN4–5 showed higher RFU at concentration of 200 μg/mL, while AN3 did not show significant variation in RFU as compared to vehicle-treated (1% DMSO) cell culture.

Fig. 4.

a In vitro Caspase 3/7 activity of anthocyanins against C-6 cells by Apo-ONE homogeneous Caspase-3/7 assay kit (Promega). b In vitro immunostimulatory activity of anthocyanins against human PBMCs by Lymphocyte proliferation assay

Lymphocyte proliferation assay-immunostimulatory activity

Anthocyanins were tested at different concentrations (50–200 µg/mL) against human lymphocytes in vitro by lymphocyte proliferation assay in absence and presence of mitogens (PHA). Percentage of lymphocyte proliferation was determined by concentration of formazan formed from exogenous MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide]. Anthocyanins were found to induce human mononuclear cell growth, with average percentage of 2.4–122.2% in the absence of mitogen PHA, and 0.2–68.7% in the presence of PHA (Fig. 4b). All the compounds showed higher proliferation at concentration 200 μg/mL in absence and presence of PHA and were significantly higher than the positive control (PHA) for cell proliferation when incubated in culture at concentration of 5 μg/mL.

Discussion

Anthocyanins and flavan-3-ols are end products of flavonoid pathway in plants (Peng et al. 2012). Anthocyanins are formed from precursors like dihydroflavonols that act as substrate for FLS and DFR. DFR enzyme diverts the carbon flux towards anthocyanin biosynthesis at the cost of flavonol (catechins) biosynthesis (Hua et al. 2013). Higher transcript expression levels of CsDFR, and CsANS and lower transcript expression levels of CsFLS genes documented the diversion of carbon flux toward anthocyanin accumulation in purple tea. The higher transcripts level of CsLAR and CsANR genes in purple tea has also indicated their involvement in anthocyanin accumulation. The deletion mutants of the DFR encoding gene in Allium cepa were the limiting factor that led to absence of DFR activity and decrease the anthocyanin accumulation (Kim et al. 2005). Similarly, silencing of IbDFR gene was reported with decreased anthocyanin accumulation and increased flavonol influx (Wang et al. 2013). The up-regulation of transcript levels of DFR and ANS gene in developing blueberries also increased in concurrence with the accumulation of anthocyanins. Hence, genes of anthocyanin biosynthesis demonstrate the coordinated expression with anthocyanin accumulation in purple tea.

Variations were observed in content of anthocyanins in new purple tea clones. The presence of anthocyanins in purple coloured tea clone IHBT-269 was detected by UV–Vis absorption spectra at 520 nm (Fig. S2). Four anthocyanins (AN1–4) were isolated using amberlite XAD-16 column chromatography followed by repeated C18 column. Repeated C-18 flash chromatography has also been used for purification (Jiang et al. 2013). Anthocyanins are incorporated as structurally intact glycoside and absorbed absorption from the digestive tract into blood circulation system (Lila 2004). In vitro methods have the advantage of being more rapid, less expensive, less labor intensive and do not have ethical restrictions. Moreover, anthocyanin uptake from blood into kidney tubular cells is likely to be mediated by the kidney isoform of this organic anion membrane transporter (Spencer and Crozier 2012). Anthocyanins played a significant role in conventional treatments such as preventive agents against different forms of cancers, cardiovascular disorders and anti-inflammatory diseases. Anthocyanins have been shown to suppress or block cancer progression by a variety of mechanisms by acting as anti-proliferative agents and as antioxidants (Lee et al. 2009).

Recent studies have shown that anthocyanins are affected by environmental factors, likewise high temperature lowers their accumulation in plant leaves, fruits and flowers. Cyanidin-3-glucoside (AN1), cyanidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside (AN2), delphinidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside (AN3), cyanidin-3-O-(2-O-β-xylopyranosyl-6-O-acetyl)-β-glucopyranoside (AN4) and crude extract (AN5) from purple tea shoot clones exhibited potent radical-scavenging activities as compared to ordinary green leaf tea shoot clones (Kerio et al. 2012). This can be attributed to synergistic effects of all anthocyanins, as well as positively charged oxygen atom in anthocyanins that makes it a distinct hydrogen-donating compound as compared to other flavonoids such as catechins. Cyanidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside (AN2) showed higher antioxidant activity confirmed by its lower IC50 values by DPPH and ABTS assays. Antioxidant efficiency of anthocyanins has been shown to be related to several parameters like the number of hydroxyl groups in the molecule, the catechol moiety in the B-ring, the oxonium ion structure in the C-ring, hydroxylation and methylation pattern and to the acylation by phenolic acids (Kim et al. 2005). Higher antioxidant activity of anthocyanin molecule had been attributed to their ability to delocalize electrons to form resonating structures after change in pH, a characteristic feature that is missing in other antioxidants (Bagchi et al. 2006).

Previous reports have shown cytotoxic properties of anthocynins isolated from plants against human cancer cell lines (Tsuda 2012). Anthocyanins are considered as potential inhibitors of cancer cell proliferation (Reddivari et al. 2007). Apoptosis is the most potent defense mechanism against cancer and its intrinsic pathway involves permeabilization of mitochondrial membrane to release apoptogenic mitochondrial proteins such as cytochrome C (Sheridan et al. 2008). Present study showed the induction of apoptosis by anthocyanins of purple tea in C-6 cells supporting them as highly promising cancer chemopreventive constitutions. Apoptosis is orchestrated by a family of cysteine proteases i.e. caspases, which are activated in response to pro-apoptotic stimuli.

Caspases promote mainly apoptosis by inducing destructive DNases enzymes and destroying key regulatory and structural proteins. Based on their roles Caspases are divided mainly into two subgroups in the upstream and downstream processes of apoptosis (Slee et al. 2001). Present study investigated the growth inhibitory effects of AN5 and AN1–4 anthocyanins using A549 cells and C-6 cancer cell lines, respectively. Apart from the numerous health-promoting properties of teas, very little work has been performed to investigate anticancer activity of these anthocyanins from these newly bred purple-shoot tea clones. Higher anticancer activity was shown by cyanidin-3-glucoside (AN1), cyanidin-3-O-β-d-(6-(E)-coumaroyl) glucopyranoside (AN2), cyanidin-3-O-(2-O-β-xylopyranosyl-6-O-acetyl)-β-glucopyranoside (AN4) and crude extract (AN5) on C-6 cells at concentration of 200 μg/mL. AN3 did not show any significant effect on C-6 cells. AN5 also inhibited the proliferation of COLO 320DM (IC50 = 64.9 μg/mL) and HT-29 (IC50 = 55.2 μg/mL) by blocking cell cycle progression during G0/G1 phase and inducing apoptotic death and shown higher inhibitory efficacy than ordinary green tea (Chih-Ping et al. 2012). Principle component analysis was applied as a visualisation technique for correlation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of anthocyanins AN1–5. By applying this method, two components were extracted which explained up to 94.33% of the total variance. Figure 5 showed score plot in principle component 1 (PC1) and principle component 2 (PC2) based on IC50 values of AN1–5. Only AN3 appears on the positive side of component 1 and correlated well with ABTS (Fig. 5), which implies that AN3 has high antioxidant activity but low anticancer activity. On the other hand, AN4 correlated well with DPPH but in negative coordinate implying lower DPPH antioxidant activity with increase in concentration. A strong correlation was observed in AN1, AN2 and AN5 with anticancer activity in positive side of component 2. This correlated well with the activity of caspase-3/7 which increased in C-6 cells when treated AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins compared with vehicle-treated cell cultures (Fig. 4a). These results clearly suggest that AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins induced apoptotic cell death through caspase-3 and caspase-7 dependent processing in C-6 cells. The mechanism of apoptosis induced by AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins is not yet completely understood. However, the effect of AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins on A549 cells was not significant. Higher RFU was shown by AN1, AN2, AN3 and AN5 at concentration of 200 μg/mL while AN4 did not show significant RFU compared to the vehicle-treated (1% DMSO) cell culture, suggesting that the inhibition in cells was due to apoptosis induced by AN1–3 and AN5 anthocyanins.

Fig. 5.

Principle component analysis (PCA) of correlation among the antioxidant analysis of anthocyanins with anticancer activity

Polyphenols such as flavonoids, tannins and anthocyanins are potential antioxidant compounds that might contribute to immunostimulatory effect by promoting changes in redox-sensitive signaling pathways involved in certain genes expression. These kinds of changes will further influence several cell functions including immune response (Ramiro-Puig and Castell 2009). Lymphocyte proliferation assay with incubation of 72 h and PHA as mitogenic stimuli was conventionally used to verify T lymphocyte activation (Bessler et al. 2005). AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins have induced human mononuclear cell growth, with average percentages of 2.4–122.2% in the absence of mitogen PHA, and 0.2–68.7% in the presence of PHA (Fig. 4b). The highest stimulation in human mononuclear cells growth was induced by AN1 in the presence of mitogen and absence of mitogen (68.7 and 122.2%, respectively) at the concentration of 200 μg/mL. In the absence of mitogens (PHA), anthocyanins AN1–4 and AN5 were not cytotoxic to lymphocytes in culture. The immune stimulating activity of AN1–4 and AN5 anthocyanins in vitro on human mononuclear cells indicated the potential of anthocyanins in promoting advancement in the field of immunotherapy.

Conclusion

Higher expression levels of CsDFR, CsANS and CsANR and lower expression levels of CsFLS and CsLAR supported the higher accumulation of anthocyanins in new purple tea clone IHBT-269. Four anthocyanins (cyanidin, cyanidin-glucoside, delphinidine and acylated glucose) were isolated and characterized by UPLC–ESI–QToF–MS/MS analysis and their comparative bioactivity studies have suggested their potential as antioxidant, immunostimulatory and anticancer. The richness of quality anthocyanins in purple tea opens high future prospects.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge financial assistance received from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, India under Main Lab Project No. MLP 0070 (Purification, characterization and bioprocessing of nutraceuticals from tea).

Abbreviation

- Cs

Camellia sinensis

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13197-017-2631-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Akiyama S, Nesumi A, Maeda-Yamamoto M, Uehara M, Murakami A. Effects of anthocyanin-rich tea “Sunrouge” on dextran sodium colitis in mice. BioFactors. 2012;38:226–233. doi: 10.1002/biof.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi D, Roy S, Patel V, He G. Safety and whole body antioxidant potential of a novel anthocyanins-rich formulation of edible berries. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;281:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-1030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessler H, Salman H, Bergman M, Straussberg R, Djaldetti M. In vitro effect of statins on cytokine production and mitogen response of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Immunol. 2005;117:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih-Ping H, Yi-T Shih, Lin B-R, Chiu C-F, Lin C-C. Inhibitory effect and mechanisms of an anthocyanins- and anthocyanidins-rich extract from purple-shoot tea on colorectal carcinoma cell proliferation. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:3686–3692. doi: 10.1021/jf204619n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua C, Linling L, Shuiyuan C, Fuliang C, Feng X, Honghui Y, Conghua W. Molecular cloning and characterization of three genes encoding dihydroflavonol-4-reductase from Ginkgo biloba in anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Shen X, Shoji T, Kanda T, Zhou J, Zhao L. Characterization and activity of anthocyanins in Zijuan tea (Camellia sinensis var. kitamura) J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:3306–3310. doi: 10.1021/jf304860u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Sood S, Dogra P, Mahendru M, Kumar D, Bhangalia S, Pal HC, Kumar N, Bhushan S, Gulati A, Saxena AK, Gulati A. In vitro cytotoxicity, antimicrobial, and metal-chelating activity of triterpene saponins from tea seed grown in Kangra valley, India. Med Chem Res. 2012;22:4030–4038. doi: 10.1007/s00044-012-0404-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Rana A, Gulati A. Studies on quality of orthodox teas made from anthocyanin-rich tea clones growing in Kangra valley, India. Food Chem. 2015;176:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassim A, Poette J, Paterson A, Zait D, McCallum S, Woodhead M, Smith K, Hackett C, Graham J. Environmental and seasonal influences on red raspberry anthocyanin antioxidant contents and identification of quantitative traits loci (QTL) Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53:625–634. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerio LC, Wachira FN, Wanyoko JK, Rotich MK. Total polyphenols, catechin profiles and antioxidant activity of tea products from purple leaf coloured tea cultivars. Food Chem. 2012;136:1405–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Yoo KS, Pike LM. Development of a PCR-based marker utilizing a deletion mutation in the dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) gene responsible for the lack of anthocyanin production in yellow onions (Allium cepa) Theor Appl Gen. 2005;110:588–595. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1882-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S-J, Jung Y-S, Lee S-H, Chung H-Y, Park B-J. Isolation of a chemical inhibitor against K-Ras-induced p53 suppression through natural compound screening. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1637–1643. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J-B, Hashimoto F, Shimizu K, Skata Y. Anthocyanins from red flowers of Camellia cultivar ‘Dalicha’. Phytochem. 2008;69:3166–3171. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J-B, Hashimoto F, Shimizu K, Skata Y. A new acylated anthocyanin from the red flowers of Camellia hongkongensis and characterization of anthocyanins in the section Camellia species. Int J Plant Biol. 2009;51:545–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2009.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lila MA. Anthocyanins and human health: an in vitro investigative approach. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2004;5:306–313. doi: 10.1155/S111072430440401X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-C, Hsu C-P, Chen CC, Liao TZ, Chiu C-F, Lien PJ, Shih YT. Anti-proliferation and radiation-sensitizing effect of an anthocyanidin- rich extract from purple-shoot tea on colon cancer cells. J Food Drug Anal. 2012;20:328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Osman H, Rahim AA, Isa NM, Bakhir NM. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of paederia foetida and Syzygium aqueum. Molecules. 2009;14:970–978. doi: 10.3390/molecules14030970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q-Z, Zhu Y, Liu Z, Du C, Li K-G, Xie D-Y. An integrated approach to demonstrating the ANR pathway of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in plants. Planta. 2012;236:901–918. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1670-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro-Puig E, Castell M. Cocoa: antioxidant and immunomodulator. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:931–940. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508169896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddivari L, Vanamala J, Chintharlapalli S, Safe SH, Miller JC. Anthocyanin fraction from potato extracts is cytotoxic to prostate cancer cells through activation of caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2227–2235. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Honma D, Tagashira M, Kanda T, Nesumi A, Yamamoto MM. Anthocyanins from new red leaf tea ‘Sunrouge’. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:4779–4782. doi: 10.1021/jf200250g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan C, Delivani P, Cullen S-P, Martin S-J. Bax- or Bak-induced mitochondrial fission can be uncoupled from cytochrome C release. Mol Cell. 2008;31:570–585. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slee EA, Adrain C, Martin SJ. Executioner caspase-3,-6 and -7 perform distinct, non-redundant roles during the demolition phases of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7230–7236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JPE, Crozier A. Flavonoids and related compounds: bioavailability and function. London: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group; 2012. pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda T. Dietary anthocyanin-rich plants: biochemical basis and recent progress in health benefits studies. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2012;56:159–170. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walia M, Mann T, Kumar D, Agnihotri VK, Singh B (2012) Chemical composition and in vitro cytotoxic activity of essential oil of leaves of Malus domestica growing in western Himalaya (India). Evidence-Based Com Alter Med 649727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Fan W, Li H, Yang J, Huang J, Zhang P. Functional characterization of dihydroflavonol-4-reductase in anthocyanin biosynthesis of purple sweet potato underlies the direct evidence of anthocyanins function against abiotic stresses. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z-J, Li X-H, Liu Z-W, Xu Z-S, Zhuang J. De novo assembly and transcriptome characterization: novel insights into catechins biosynthesis in Camellia sinensis. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:277. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0277-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafra-Stone S, Yasmin T, Bagchi M, Chatterjee A, Vinson JA, Bagchi D. Berry anthocyanins as novel antioxidants in human health and disease prevention. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:675–683. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.