Abstract

About 50% of the Na+ reabsorbed in thick ascending limbs traverses the paracellular pathway. Nitric oxide (NO) reduces the permselectivity of this pathway via cGMP, but its effects on absolute Na+ () and Cl− () permeabilities are unknown. To address this, we measured the effect of l-arginine (0.5 mmol/l; NO synthase substrate) and cGMP (0.5 mmol/l) on and calculated from the transepithelial resistance (Rt) and / in medullary thick ascending limbs. Rt was 7,722 ± 1,554 ohm·cm in the control period and 6,318 ± 1,757 ohm·cm after l-arginine treatment (P < 0.05). / was 2.0 ± 0.2 in the control period and 1.7 ± 0.1 after l-arginine (P < 0.04). Calculated and were 3.52 ± 0.2 and 1.81 ± 0.10 × 10−5 cm/s, respectively, in the control period. After l-arginine they were 6.65 ± 0.69 (P < 0.0001 vs. control) and 3.97 ± 0.44 (P < 0.0001) × 10−5 cm/s, respectively. NOS inhibition with Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (5 mmol/l) prevented l-arginine’s effect on Rt. Next we tested the effect of cGMP. Rt in the control period was 7,592 ± 1,470 and 4,796 ± 847 ohm·cm after dibutyryl-cGMP (0.5 mmol/l; db-cGMP) treatment (P < 0.04). / was 1.8 ± 0.1 in the control period and 1.6 ± 0.1 after db-cGMP (P < 0.03). and were 4.58 ± 0.80 and 2.66 ± 0.57 × 10−5 cm/s, respectively, for the control period and 9.48 ± 1.63 (P < 0.007) and 6.01 ± 1.05 (P < 0.005) × 10−5 cm/s, respectively, after db-cGMP. We modeled NO’s effect on luminal Na+ concentration along the thick ascending limb. We found that NO’s effect on the paracellular pathway reduces net Na+ reabsorption and that the magnitude of this effect is similar to that due to NO’s inhibition of transcellular transport.

Keywords: sodium transport, nitric oxide, paracellular permeability, kidney

as a diluting segment, the thick ascending limb reabsorbs solutes but little or no water. Net NaCl reabsorption in this portion of the nephron accounts for ~30% of the NaCl load filtered by the glomerulus (3). About one-half of the Na+ is reabsorbed through active transcellular transport. The remainder, and other cations, is reabsorbed via the paracellular pathway, or shunt, due to the lumen-positive voltage created as a consequence of active transport (13, 15). The route through the tight junctions of neighbor cells is markedly cation selective in thick ascending limbs with a Na+-to- Cl− permeability ratio (/) of approximately two (5, 11, 15).

Nitric oxide (NO) regulates salt and water reabsorption throughout the nephron (6, 17, 26, 27, 32). It is synthesized by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) from its substrate l-arginine. All three NOS isoforms (neuronal, inducible, and endothelial) are expressed in mammalian thick ascending limbs. NO reduces the activity of transporters in the luminal membrane and thereby transepithelial NaCl and NaHCO3 reabsorption (7, 9, 31, 33, 34). We previously showed that NO decreases the / of the paracellular pathway in thick ascending limbs via cGMP (30). However, whether this is a result of a decrease in , an increase in , or a simultaneous change in both and in opposite directions, and how these changes alter net salt reabsorption, are still unknown.

To calculate absolute permeabilities, one must know the transepithelial resistance (Rt), which is a measure of the hinderance encountered by ions traversing an epithelia through both trans- and paracellular conductive pathways. In thick ascending limbs Rt, or its inverse conductance, is predominantly a reflection of the ionic permeability of the paracellular pathway, determined by the barrier function of the tight junctions (10, 12, 40). Changes in these variables can affect net solute transport. Rt of rat thick ascending limbs has not been reported nor has the effect of endogenously produced NO on this parameter.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of NO on 1) thick ascending limb Rt; 2) the mechanism of action; 3) the absolute permeabilities of both Na+ and Cl−; and 4) how it impacts net Na+ reabsorption.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and solutions.

Tubules were perfused and bathed with physiological saline, containing (in mmol/l): 130 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2.5 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 6 l-alanine, 1 Na3-citrate, 5.5 glucose, 2 Ca(lactate)2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 at 37°C, unless otherwise stated. The final concentrations of Na+ and Cl− were 142 and 134 mmol/l, respectively. l-Arginine, the substrate for NO production, and the NOS inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (l-NAME) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Dibutyryl-cGMP (db-cGMP) was from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY).

Animals.

All protocols requiring animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 120–150 g (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were maintained on a diet containing 0.24% sodium and 1.1% potassium (Purina, Richmond, IN) for at least 4 days before use.

Isolation and perfusion of thick ascending limbs.

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (100 and 20 mg/kg ip body wt, respectively). An abdominal incision was made, and the left kidney was removed and bathed in ice-cold physiological saline. The capsule was removed, and coronal slices were cut. Thick ascending limbs were dissected from the outer medulla under a stereomicroscope at 4–10°C and placed in a temperature-regulated chamber (37 ± 1°C) with a flowing bath (1 ml/min). Tubules were perfused as described (4, 8).

Measurement of Rt.

Before the experiment the injection artifact of the system was assessed by injecting current pulses of ±100 nA for 1 s four times in absence of the tubule. This procedure was also repeated at the end of the experiment after the tubule was released. Voltage deflections resulting from pulse injections were measured with three calomel electrodes and 150 mM NaCl, 4% agar bridges connected to two electrometers in contact with the perfusion (Axoprobe 1A; Axon Instruments) and collecting pipettes (Neuroprobe Amplifier; A-M Systems), and bath which was grounded. Values were recorded with a PowerLab acquisition system and PowerChart8 software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO). To measure Rt, isolated tubules were transferred to the chamber, bathed, and perfused with physiological saline. After a 14-min equilibration period, current pulses were injected (±100 nA) over 1 min under control conditions. Following, the test compound was added to the bath, a 15-min incubation period was allowed, and the injection procedure was repeated. The baseline voltage and the artifact of injection were subtracted from the mean voltage deflection caused by the current pulses to obtain the corrected voltage deflections for each period. The corrected voltages were used to calculate the Rt for each period using cable analysis, as follows,

| (1) |

| (2) |

where L is length of tubule, λ is a space constant, h indicates a hyperbolic function, Vo is voltage registered at the proximal end, V1 is voltage registered at the distal end, and I0 is current injected at the proximal end. Results were expressed as specific Rt, which is the Rt normalized to unit length.

Measurement of dilution potentials and calculation of /.

Tubules were initially bathed and perfused in symmetrical physiological saline for a 15-min equilibration period. Transepithelial voltage was measured with two calomel electrodes and 150 mM NaCl, 4% agar bridges connected to an electrometer in contact with the perfusion pipette (Axoprobe 1A; Axon Instruments) and bath that was grounded. Voltages were recorded as described for Rt experiments. Thick ascending limbs were then bathed for an additional 6 min, and basal voltages were recorded during the last minute of this period. The bath was then changed to a solution based on physiological saline in which Na+/Cl− were reduced to 32/24 mmol/l, respectively (all other compounds in the solution remained the same), for 6 min. The osmolality was maintained at 290 mosmol/kgH2O using mannitol. The resulting difference in transepithelial voltage measured 1 min after the exchange was considered the dilution potential of the control period. The bath was then restored to physiological saline for 12 min to allow tubules to recover. l-Arginine (0.5 mmol/l), dibutyryl-cGMP (100 μmol/l) or vehicle was then added to the bath. Later (20 min) the process was repeated in the presence of test compounds as indicated in the text. When l-NAME (5 mmol/l) was used to inhibit NO synthesis, it was present from the beginning of the experiment. All dilution potentials were corrected for liquid junction potentials. / values were calculated from dilution potentials using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) equation as we have done previously (30).

Calculation of absolute permeabilities.

From the Rt values and /, we calculated absolute and with the Kimizuka-Koketsu equation (18, 19):

| (3) |

| (4) |

where G is specific conductance, the inverse of specific Rt; R is ideal gas constant; T is temperature in degrees Kelvin; F is Faraday’s constant; α is NaCl concentration; and β is /.

Mathematical modeling of luminal Na+ concentration along the thick ascending limb.

A simple mathematical model of the luminal Na+ concentration ([Na+]i) along the thick ascending limb was developed following the approach of Layton et al. (21) and Layton and Edwards (20). The model assumed that: 1) the thick ascending limb is rigid extending from the bottom of the outer medulla (x = 0) to the top of the cortex (x = L), and the cortical-medullary junction is located at x = x*; 2) x is positive in the direction of the constant fluid flow Q along the tubule; and 3) the amount of Na+ in the lumen (Q × [Na+]i) changes along the tubule because of the rate of Na+ reabsorption (J). Thus the solute conservation equation for luminal [Na+]i along the thick ascending limb at steady state is given by the first-order ordinary differential equation (ODE)

| (5) |

where r is the radius of the tubule (21). Because J depends on 1) active transcellular transport (JA) mediated by the apical Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and the basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase and 2) transport through the passive paracellular pathway (JP) mediated by the lumen-positive voltage (Vm), it can be written that

| (6) |

JA follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics, that is

| (7) |

where the maximal velocity Tmax is assumed to be 400 pmol·mm−1·min−1 similar to what has been done previously (21). This yields a physiologically relevant [Na+]i of ~25 mmol/l (2) at the end of the tubule. The value of Km is 30 mmol/l, an average of the Km for Cl−. The average Km for Cl− of the different NKCC2 isoforms present in the outer medulla and cortex was used since 1) it is an obligatory cotransported anion with Na+ in thick ascending limbs, and 2) it is the rate-limiting ion for transcellular Na+ reabsorption.

JP follows the GHK equation

| (8) |

where [Na+]o is the interstitial Na+ concentration. Because [Na+]o depends on transport and JA decays exponentially, [Na+]o was assumed to decay exponentially from the initial interstitial {[Na+]o,initial (at x = 0)} to the final interstitial {[Na+]o,final (at x = L)} according to the equation

| (9) |

Here, considering that outer medullary osmolality is ~350–400 mosmol/kgH2O (16), [Na+]o,initial was chosen to be 175 mmol/l. Cortical osmolality is 290 mosmol/kgH2O, and therefore the value of [Na+]o,final was chosen to be 140 mmol/l. Moreover, because of the high perfusion rates in the cortex, [Na+]o reaches its minimum value of 140 mmol/l (i.e., [Na+]o,final) at the cortical-medullary junction (i.e., at x = x*). The value of the rate constant τ, chosen to be 0.03, guarantees that [Na+]o reaches its minimum value of 140 mmol/l at x* = 0.18 cm, 30% of the total tubular length (L, 0.6 cm) tubule.

Finally, because Vm is influenced by both the active and passive transport, it was written that

| (10) |

Here, because the active component of the voltage (VA) is due to the active transport JA, and, because JA follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics (see Eq. 7), it was assumed that VA also follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics according to the equation

| (11) |

with Km the same as in JA, and Vmax is the maximal lumen-positive voltage of 10 mV measured at the beginning of the tubule when JA is at a maximum.

In Eq. 10, the passive component of the voltage (VP) is given by the Nernst equation

| (12) |

Alpha (α) is a factor used to correct VP. It corrects VP to compensate for the fact that we are not accounting for the effect of Cl− on VP in our simple model. Thus, to obtain a “physiological voltage” due to the paracellular component, one must multiply VP by α. The total transepithelial voltage is then given by Eq. 10. α is calculated as the ratio between the membrane voltage predicted by the GHK equation for both Na+ and Cl− (VP,GHK) and by the Nernst equation for Na+ only (VP,Nernst). The Na+ and Cl− concentrations used to calculate the correction factor α were those used in the dilution potential experiments where [Na+]i,* = 142 mmol/l, [Na+]o,* = 32 mmol/l, [Cl−]i,* = 134 mmol/l, and [Cl−]o,* = 24 mmol/l.

That is,

| (13) |

Assuming that [Na+]i = 175 mmol/l at the beginning of the tubule (x = 0), r = 10 µm, and Q = 10 nl/min, the above ODE (1) was solved in Matlab using the stiff ODE solver, ode15s.

Four simulations were performed to predict the luminal Na+ concentration along the tubule under the following conditions: 1) control, 2) considering the effect of NO on the paracellular pathway only, 3) considering the effect of NO on the transcellular pathways only, and 4) considering the effect of NO on both the paracellular and transcellular pathways combined. A control experiment was simulated by using the control and values obtained in this study and the calculated α value for these conditions. Next, the effect of NO on the paracellular pathway only was simulated by assigning and values calculated in the presence of l-arginine in this study, and the calculated α value for these conditions. The effect of NO on the transcellular pathway only was simulated by reducing the value of Tmax by 30%, that is Tmax = 280 pmol·mm−1·min−1, and by assigning and values as in the control case and the calculated α value. Finally, the effect of NO on both the paracellular and transcellular pathway was simulated by reducing the value of Tmax by 30% and by assigning to , , and α the same values used for the simulation in which we tested the effect of NO on the paracellular pathway only.

Statistical analysis.

All data were analyzed with a two-tailed Student’s t-test for paired experiments. Absolute permeabilities were calculated from / and specific transepithelial resistances by “boot strapping.” Results are presented as means ± SE. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

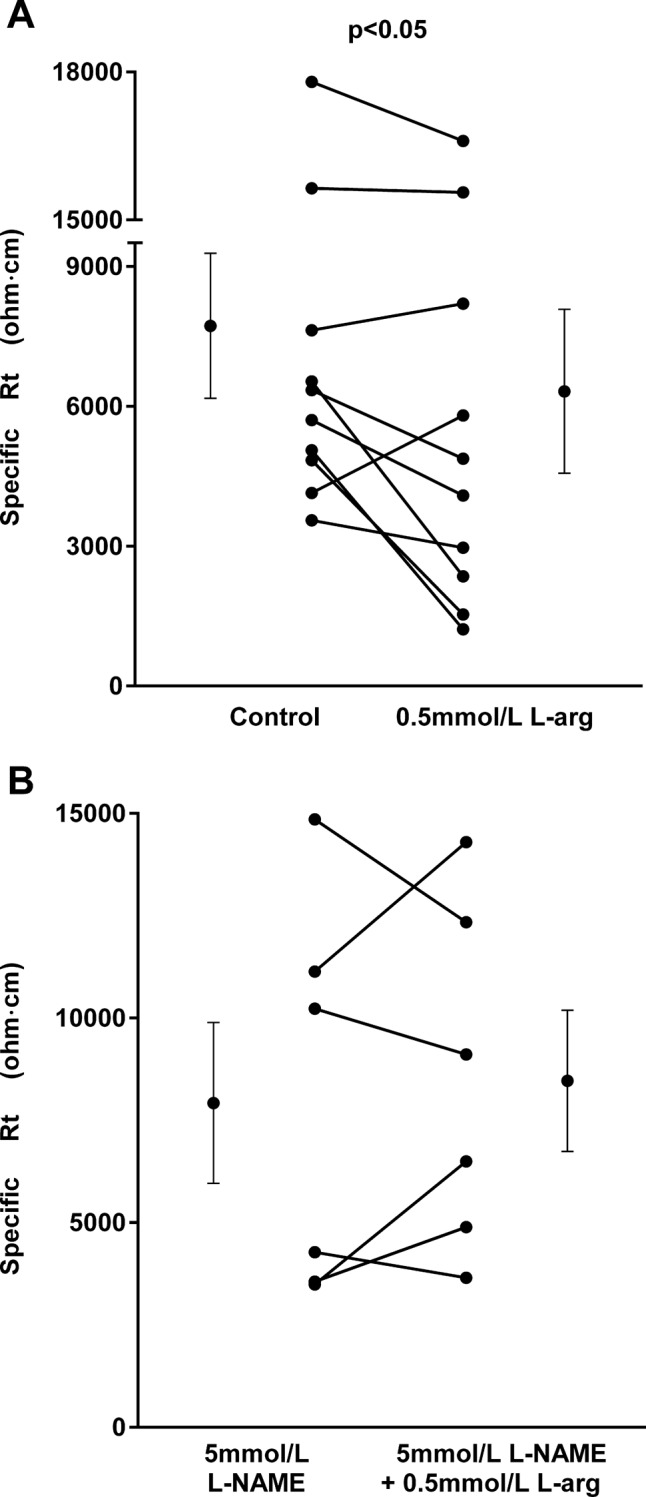

We first measured Rt and the effects of endogenously produced NO on this parameter as required to calculate absolute permeabilities of Na+ and Cl− in medullary thick ascending limbs, and the effects of NO. Additionally, these values have not been reported previously. Rt was measured by recording the voltage deflections at both proximal and distal ends of the tubule caused by current pulses in the absence or presence of l-arginine (0.5 mmol/l). During the control period, the specific Rt was 7,722 ± 1,554 ohm·cm, and it was 6,318 ± 1,757 ohm·cm after adding l-arginine to stimulate NO production (n = 10, P < 0.05; Fig 1A).

Fig. 1.

A: effect of l-arginine (l-arg) on specific transepithelial resistance (Rt; n = 10). B: effect of l-arg on specific Rt in the presence of the nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) (n = 6). Individual experiments and means ± SE are depicted.

To test whether the effect of l-arginine on Rt was due to NO, we studied the ability of l-NAME, a NO synthase inhibitor, to block its effects. In the presence of l-NAME (5 mmol/l), the specific Rt was 7,924 ± 1,964 ohm·cm. After addition of l-arginine in the presence of l-NAME, the specific Rt was 8,463 ± 1,725 ohm·cm, not significantly different from the value in the control period (n = 6; Fig. 1B). l-NAME alone did not affect Rt.

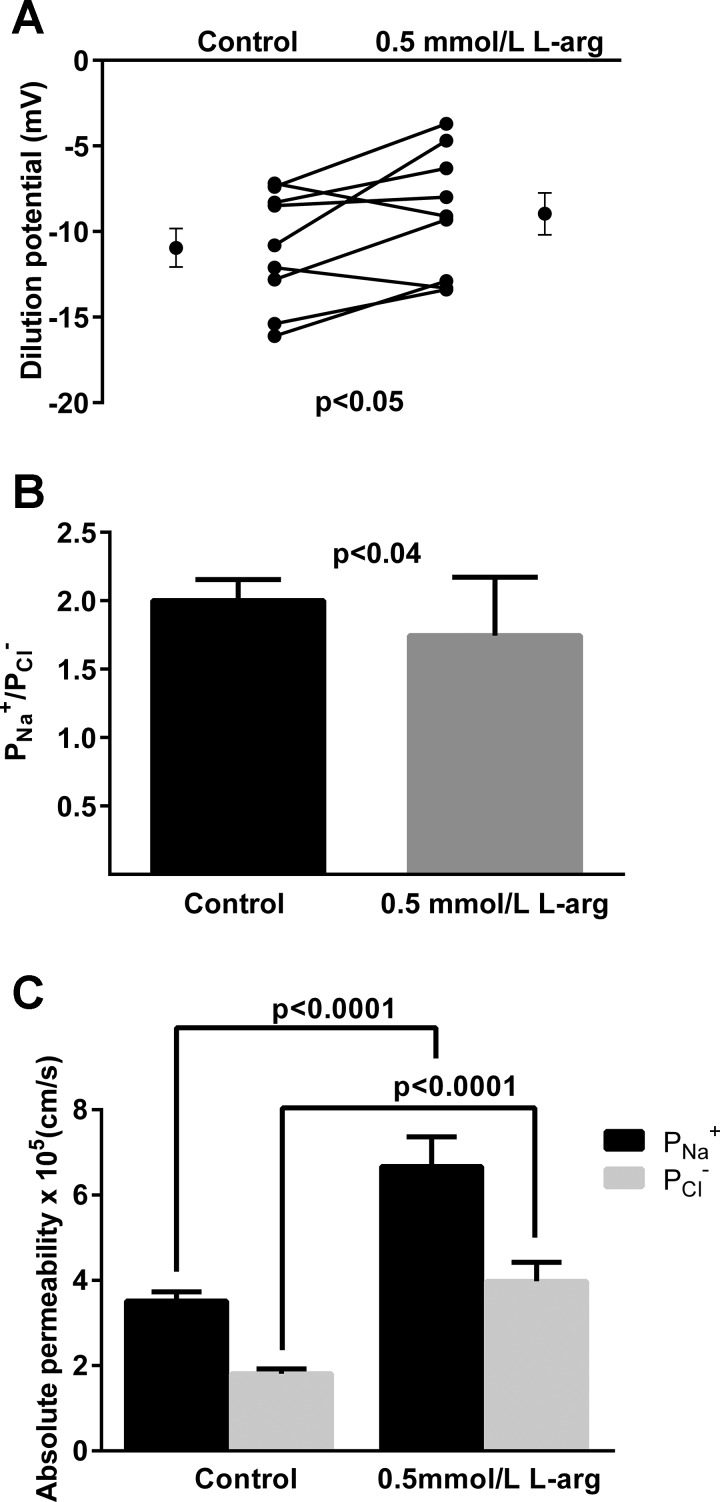

We next studied the effect of endogenous NO on dilution potentials and thus / values because these values are required to calculate absolute Na+ and Cl− permeabilities. During the control period, the dilution potential was −11.0 ± 1.1 mV. After adding l-arginine to the bath, the dilution potential was −9.0 ± 1.3 mV (n = 9, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). The calculated / was 2.0 ± 0.2 during the control period. After l-arginine it was 1.7 ± 0.1 (P < 0.04; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

A: Effect of l-arg on dilution potentials (n = 9) (A), calculated Na+-to- Cl− permeability ratio (/, B),and paracellular and (C) in thick ascending limbs (n = 50). Individual experiments and means ± SE are depicted.

Once we collected both / values and Rt data, we calculated the absolute permeabilities for Na+ and Cl−, and the effects of NO. During the control period calculated and were 3.52 ± 0.21 and 1.81 ± 0.17 × 10−5 cm/s, respectively. After adding l-arginine to stimulate NO production, they increased to 6.65 ± 0.69 (P < 0.0001 vs. control) and 3.97 ± 0.44 (P < 0.0001 vs. control) × 10−5 cm/s, respectively (n = 50; Fig. 2C).

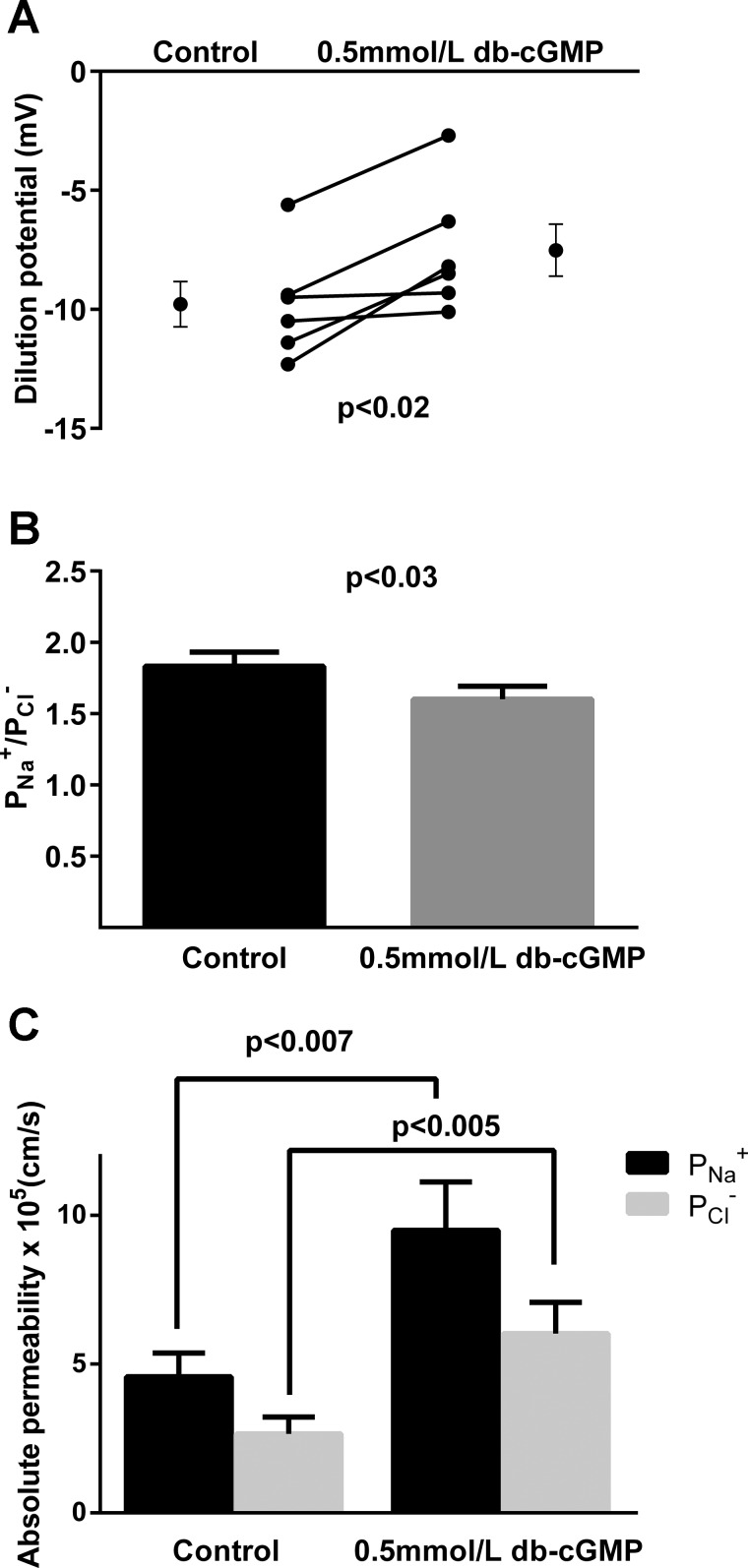

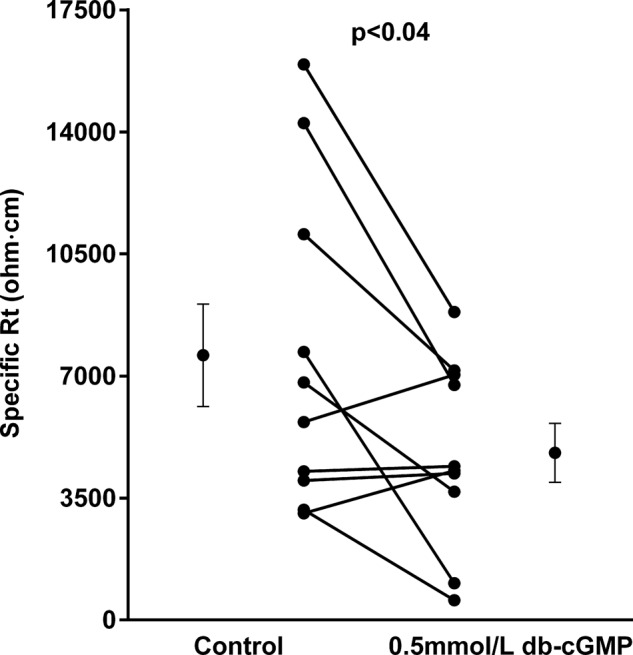

We then investigated the effect of the membrane-permeant cGMP analog db-cGMP on Rt in this segment. During the control period, the specific Rt was 7,592 ± 1,470 ohm·cm. After db-cGMP (0.5 mmol/l) it was 4,796 ± 847 ohm·cm (n = 10, P < 0.04; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of cGMP on specific Rt in thick ascending limbs (n = 10). Individual experiments and means ± SE are depicted.

We next studied the effect of db-cGMP on dilution potentials. During the control period, the dilution potential was −9.8 ± 1.0 mV. After adding db-cGMP, the dilution potential was −7.5 ± 1.1 mV (n = 6, P < 0.02; Fig. 4A). The calculated / was 1.8 ± 0.1 during the control period and 1.6 ± 0.1 after db-cGMP treatment (n = 6, P < 0.03; Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of cGMP on dilution potentials (n = 6) (A), calculated / (B), and paracellular and (C) in thick ascending limbs (n = 50). Individual experiments and means ± SE are depicted.

Using the / and Rt, we calculated the effects of db-cGMP on and as for NO. During the control period, and were 4.58 ± 0.80 and 2.66 ± 0.57 × 10−5 cm/s, respectively. After db-cGMP treatment they were 9.48 ± 1.63 (P < 0.007 vs. control) and 6.01 ± 1.05 (P < 0.005 vs. control) × 10−5 cm/s, respectively (n = 50; Fig. 4C).

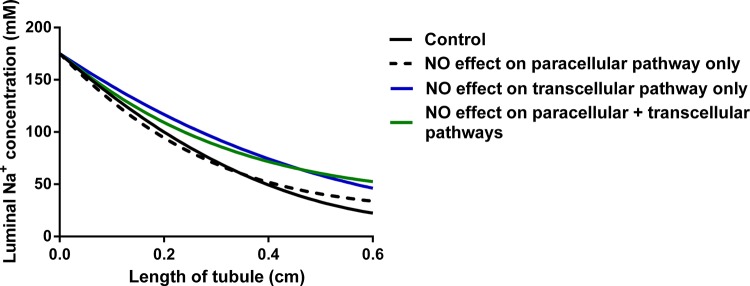

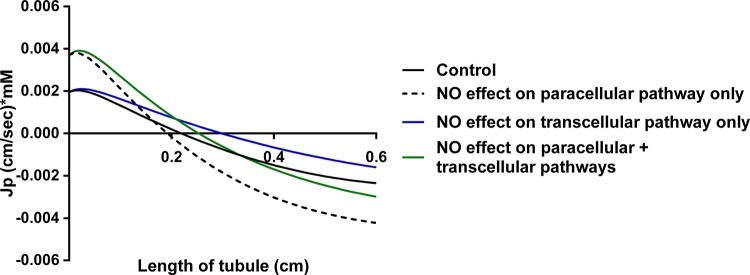

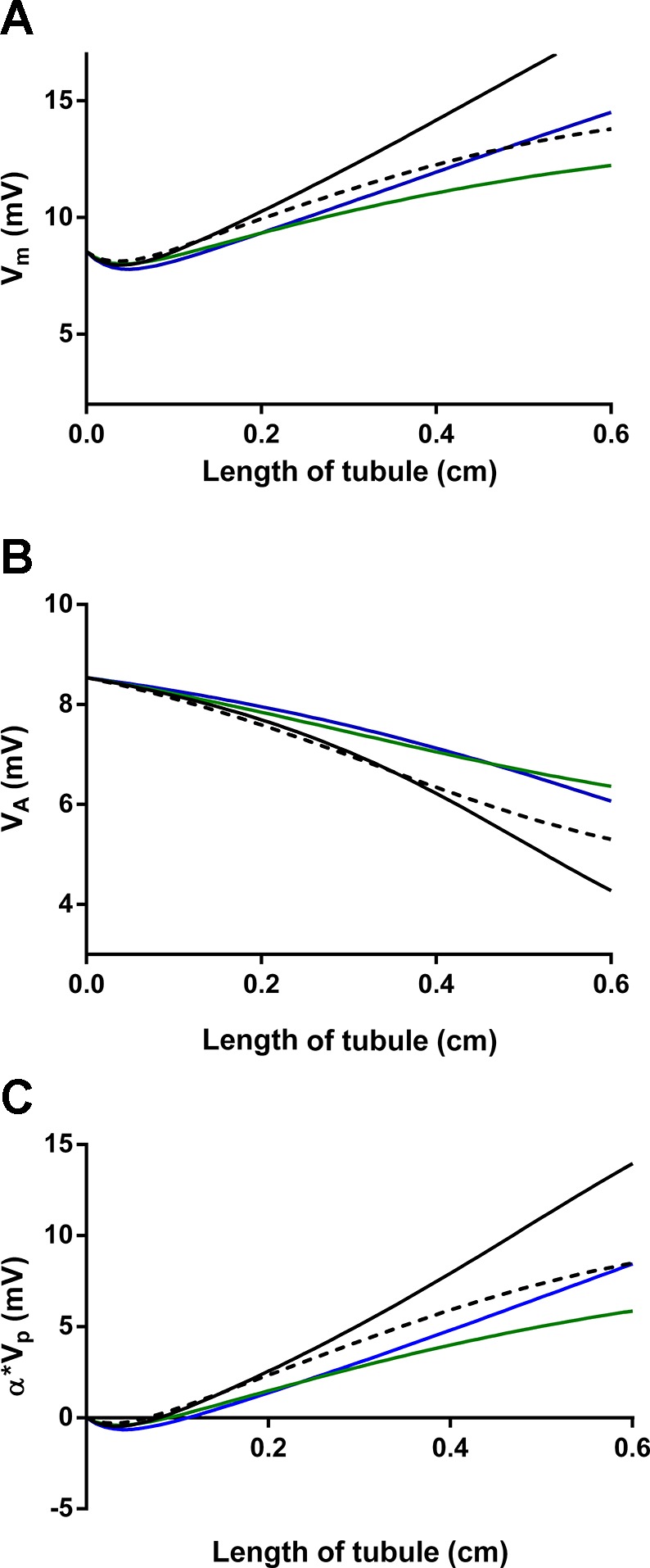

The changes in permeabilities of Na+ and Cl− caused by NO could either blunt the inhibitory effect of NO on transcellular transport by increasing salt flux through the paracellular pathway or they could augment the inhibitory effect by reducing reabsorption via this route. To address this question, we designed a mathematical model to predict the effect of NO on luminal Na+ concentration. Figure 5 shows the model’s predictions as a function of tubular length. The solid black line represents the control conditions using an α value of 0.28 (the correction factor used to account for the effect of Cl− as described in materials and methods). The broken line takes into account the effect of NO only on the paracellular pathway using an α value of 0.22. The blue line takes into account the effect of NO only on the transcellular pathway (blue line) using an α = 0.28. The green line takes into account the combined effects of NO on both the transcellular and paracellular pathways using an α value of 0.22. Under control conditions in the absence of NO, luminal Na+ falls exponentially to 22.4 mmol/l by the end of the thick ascending limb. When only the effect of NO on the paracellular pathway was considered, Na+ reabsorption was augmented early in the thick ascending limb, but, by the end of the tubule, the Na+ concentration was 33.9 mmol/l, much greater than the control condition. The same was true when considering the effect of NO on the transcellular pathway only, which results in a luminal concentration of Na+ at the end of the tubule of 46.2 mmol/l. When the effects of NO on both transcellular and paracellular pathways were included in the model, the luminal Na+ concentration was always greater than control and by the end of the tubule was 52.5 mmol/l.

Fig. 5.

Effect of NO on the luminal Na+ concentration along the thick ascending limb as predicted by mathematical modeling. Each line shows the steady-state concentration of luminal Na+ along the tubule.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this work was to investigate the effect of NO on the paracellular pathway of thick ascending limbs and its impact on net Na+ reabsorption. We found that 1) endogenously produced NO decreases Rt; 2) inhibition of NOS prevents the decrease in Rt; 3) NO reduces / in thick ascending limbs; 4) NO increases absolute and , but the increase of is greater; 5) cGMP mimics the effects of NO on /, Rt, , and ; 6) the effects of NO on the paracellular pathway reduce Na+ reabsorption; and 7) the contributions of NO-induced inhibition of paracellular and transcellular Na+ reabsorption to the reduction in net Na+ transport are equal.

We first studied the effect of NO on Rt, which assesses predominantly paracellular permeability to ions in this segment (10). Rt in rat thick ascending limbs and the effects of NO have not been reported previously. We found that the specific Rt was ~7,700 ohm·cm (~46 ohm·cm2) during the control period and that it decreased when l-arginine, the substrate for NO production, was added. This effect was blocked by the NOS inhibitor l-NAME. These results show that NO induces changes in the barrier function of the tight junctions.

We next studied the effect of NO on /, an indicator of paracellular permselectivity, which was calculated from Na+/Cl− dilution potentials. Dilution potentials arise from the movement of ions through the tight junctions down their concentration gradient, which is dependent on the charge/size selectivity of the paracellular space. We found a / of 2 during the control period, whereas, in the presence of NO, / decreased to ~1.7. These data indicate that NO regulates the relative and differently. However, this ratio alone does not provide information of how the absolute individual permeabilities are affected by NO.

With both Rt and / values, we calculated the absolute permeabilities for Na+ and Cl−. We found that NO increased both and , but increased more. These are the first data showing that NO has an effect on absolute and in any nephron segment. Because NO increases more than , the effects of NO on the paracellular pathway likely further reduce the lumen-positive potential normally generated in thick ascending limbs by active transport.

cGMP mediates most of the effects of NO. Thus we tested the effect of this signaling molecule on Rt and /. cGMP caused a decrease in Rt and an increase in both and comparable to those evoked by NO. These data suggest that the second messenger mediating the final effect of NO on Rt, absolute permeabilities, and possibly solute reabsorption via the paracellular pathway is cGMP.

Finally, we used a simple mathematical model to investigate the effect of NO on luminal Na+ concentration along the length of the thick ascending limb based on our results. Early in the tubule, at the deepest point in the outer medulla, the model predicts lower luminal Na+ concentrations (indicating that more Na+ is reabsorbed) when the effect of NO on only the paracellular pathway but not active transcellular transport is considered compared with control. This is due to high rates of transcellular transport creating a large lumen-positive voltage but still a relatively small transepithelial Na+ gradient and the increase in permeability caused by NO. However, by the end of the thick ascending limb in the cortex, the model predicts a greater luminal Na+ concentration (indicating that less Na+ is reabsorbed) in the presence of NO than its absence. This is the result of 1) active transport creating a large transepithelial Na+ gradient favoring Na+ entry in the lumen from the interstitium, i.e., back flux, 2) the increase in paracellular permeability caused by NO, and 3) the reduction in /, which diminishes the lumen-positive potential. Figures 6 and 7 show plots for JP and Vm (and its components VA and α*VP) along the length of the tubule. Backflux is evident under all conditions, but, when analyzing JP, backflux begins earlier in the tubule and is more pronounced throughout the remainder of the tubule when the effect of NO only on JP is taken into account. This is consistent with the reduction in /.

Fig. 6.

Effect of NO on transport through the passive paracellular pathway (JP) along the thick ascending limb as predicted by mathematical modeling.

Fig. 7.

Effect of NO on lumen-positive voltage (Vm, A) and its components the active component of the voltage (VA, B) and α*VP (C) along the thick ascending limb as predicted by mathematical modeling. Each line indicates an effect on the paracellular pathway only (broken line), transcellular pathway only (blue line), both combined (green line), or control (solid black line).

When the effects of NO on both the paracellular pathway and active transcellular transport are considered, the results are somewhat different. Now, the luminal Na+ concentration in the presence of NO is always greater along the tubule when compared with the control condition. This is because of several factors, including 1) the direct inhibition of active transport, 2) a reduction in the lumen-positive voltage, which diminishes part of the driving force for Na+ reabsorption via the paracellular pathway, and 3) the increase in paracellular pathway permeability, which allows a larger back flux of Na+ from the interstitium in the lumen. Although the effect of NO on each pathway analyzed individually shows an inhibitory effect on Na+ reabsorption leading to a higher luminal Na+ concentration at the end of the tubule, they are antagonistic, with the combined action being less than the sum of the individual effects.

One important caveat of the model is that we have assumed that NO has the same effect on trans- and paracellular transport in both medullary and cortical thick ascending limbs. This may or may not be a completely valid assumption because the effects of NO have not been studied on cortical thick ascending limb salt reabsorption to our knowledge, and cortical and medullary thick ascending limbs respond differently to some regulatory factors.

In our experiments we assumed that the change in Rt observed in the presence of NO was primarily the result of changes in paracellular ionic permeability rather than to specific transcellular resistance. This assumption is supported by several lines of evidence. First, / was reduced by NO. This can only occur because of a change in the paracellular pathway since there is no Na+ or Cl− conductance in thick ascending limb luminal membranes. To date, no one has reported the effects of NO on Rt or specific transcellular and paracellular resistance individually. We have shown previously that, within the time frame of the current experiments, NO does not alter Na+-K+-ATPase activity (38).

There is one report by Wu et al. (42) of an inhibitory effect of NO on the 10-pS Cl− channel in mouse cortical thick ascending limbs. However, our studies were performed in medullary thick ascending limbs, and Winters et al. (41) reported an 80 rather than a 10-pS Cl− channel in medullary thick ascending limbs. As a result, it is not clear whether inhibition of the 10-pS Cl− channel by NO is relevant to our study. Furthermore, although the 7- to 9-pS Cl− channel may be the most abundant in terms of numbers, it only carries slightly more current than the 45-pS channel when factors such as single channel conductance, open probability, etc., are taken into account. These data suggest that the effect of NO on the 10-pS channel may be not critically important to the overall resistance measurement.

There is some evidence that NO stimulates luminal membrane-rectified K+ channels (ROMK) in rat thick ascending limbs (25, 39). If NO had both a stimulatory effect on ROMK and inhibitory effect on 10-pS Cl− channels as discussed above and we took them into account, they would nearly cancel each other out, resulting in a very small quantitative change in our results.

The Rt values reported in the literature for the thick ascending limb range between 11 and 50 ohm·cm2 in mouse (14) and ~24–35 ohm·cm2 (5, 11) in rabbit. The Rt calculated in our experiments falls within these values. The difference between mouse and rat Rt values in this segment could reflect true species differences or be because of the use of varying techniques used to calculate Rt.

In our experimental design, / values calculated from dilution potential experiments reflect the permselectivity of the paracellular pathway. In these experiments, we reduced bath NaCl, and not the luminal solution. Thus, active transcellular NaCl transport was not significantly changed by the solution switch. The value of two found in the control period is in accordance with that described in the literature for thick ascending limbs and indicates that the paracellular pathway is two times as selective to Na+ than it is for Cl− (5, 11, 15). The reduction to 1.7 by NO is similar to what we have previously reported (30). Increasing evidence shows that the paracellular permselectivity is determined by claudin proteins in the tight junctions of epithelial tissues. The thick ascending limbs express claudin-3, -10, -11, -16, and -19 (1, 43). Some reports indicate that NO can interact with claudin proteins and regulate their expression/function in other systems (24, 28, 29); thus, this could be occurring in our model.

We previously found that l-NAME inhibition of NOS has no effect on chloride reabsorption in isolated perfused thick ascending limbs (35) due to our experimental conditions. We use l-arginine-free solutions both in the lumen and the bath, so the l-arginine contained in the cell is transported out of the cell favored by its concentration gradient. Because the bath is renewed continuously, there is no l-arginine in our experimental design. Therefore, all protocols where the effect of endogenously produced NO was evaluated required the addition of l-arginine. The exact concentration of l-arginine in the outer medulla has not been determined, but it has been reported to be ~0.5 mM in whole kidney (36); hence, the concentration used in our experiments falls within the physiological range.

Our findings that NO regulates paracellular permeability are in agreement with a report by Liang and Knox (23). Using the NO donor nitroprusside, these authors found that NO caused an increase in d-[3H]mannitol flux in OK cells, commonly used as an in vitro proximal tubule model. However, they did not measure the effects of nitroprusside on absolute and/or . Similarly NO has been shown to increase paracellular permeability in nonrenal epithelia. Data from Trischitta et al. (37) suggest that NO modulates intestinal paracellular permeability by increasing conductance to ions. NO has also been shown to raise permeability by causing tight junction disassembly and gut barrier dysfunction (42).

We previously reported that the effects of NO on the permselectivity of the paracellular pathway in thick ascending limbs were mediated by cGMP (30), but no conclusion could be made at the time regarding its specific effect on the absolute permeabilities of Na+ and Cl−. Our novel finding that cGMP regulates and is supported by evidence in the literature. Trischitta et al. showed that 8-bromo-cGMP, a cell membrane-permeable cGMP analog, reduced the dilution potential in eel intestine, suggesting that this second messenger could be decreasing , increasing , or affecting both in different proportion/direction. Lee and Cheng found that, whereas 4 μmol/l 8-bromo-cGMP increased Rt in Sertoli cells, therefore promoting tight junction assembly, 0.1–1 mmol/l had the opposite effect. These data indicate that this second messenger has a biphasic effect where a low dose of cGMP lowers ionic permeability and a higher dose increases ionic permeability (22). It is not clear whether cGMP is part of the mechanism of action behind the effects of NO in OK cells by Liang and Knox (23). Incubation of the cells with a guanylate cyclase inhibitor did not prevent the increase in permeability, but it also failed to abolish the increase in cGMP. Such results may indicate that the drug was not actually inhibiting cGMP production; therefore, no conclusion can be made.

In summary, we have reported that 1) Rt in rat thick ascending limbs is similar to that of other species; 2) NO reduces Rt; 3) NO increases absolute and in this segment; 4) these effects are mediated by cGMP; and 5) perhaps most importantly, the effects of NO on the paracellular pathway reduce net Na+ reabsorption in this segment. The results presented here contribute to a better understanding on the antihypertensive effects of NO.

GRANTS

This work was in part supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-028982 and HL-070985 to J. L. Garvin and K01-DK-107787 to R. Occhipinti.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.M.M. and J.L.G. conceived and designed research; C.M.M. and R.O. performed experiments; J.L.G. analyzed data; C.M.M. and J.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; C.M.M. prepared figures; C.M.M. and R.O. drafted manuscript; C.M.M., R.O., O.P.P., and J.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; C.M.M., R.O., O.P.P., and J.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelow S, El-Husseini R, Kanzawa SA, Yu AS. Renal localization and function of the tight junction protein, claudin-19. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F166–F177, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00087.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett CM, Brenner BM, Berliner RW. Micropuncture study of nephron function in the rhesus monkey. J Clin Invest 47: 203–216, 1968. doi: 10.1172/JCI105710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burg M, Good D. Sodium chloride coupled transport in mammalian nephrons. Annu Rev Physiol 45: 533–547, 1983. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.45.030183.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burg M, Grantham J, Abramow M, Orloff J. Preparation and study of fragments of single rabbit nephrons. Am J Physiol 210: 1293–1298, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burg MB, Green N. Function of the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop. Am J Physiol 224: 659–668, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Y, Stuart D, Pollock JS, Takahishi T, Kohan DE. Collecting duct-specific knockout of nitric oxide synthase 3 impairs water excretion in a sex-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 311: F1074–F1083, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00494.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García NH, Plato CF, Stoos BA, Garvin JL. Nitric oxide-induced inhibition of transport by thick ascending limbs from Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 34: 508–513, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.34.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garvin JL, Burg MB, Knepper MA. Active NH4+ absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F57–F65, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garvin JL, Hong NJ. Nitric oxide inhibits sodium/hydrogen exchange activity in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F377–F382, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Mariscal L, Chávez de Ramirez B, Lázaro A, Cereijido M. Establishment of tight junctions between cells from different animal species and different sealing capacities. J Membr Biol 107: 43–56, 1989. doi: 10.1007/BF01871082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greger R. Cation selectivity of the isolated perfused cortical thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop of rabbit kidney. Pflugers Arch 390: 30–37, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF00582707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greger R. Ion transport mechanisms in thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop of mammalian nephron. Physiol Rev 65: 760–797, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebert SC, Andreoli TE. Ionic conductance pathways in the mouse medullary thick ascending limb of Henle. The paracellular pathway and electrogenic Cl- absorption. J Gen Physiol 87: 567–590, 1986. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.4.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hebert SC, Culpepper RM, Andreoli TE. NaCl transport in mouse medullary thick ascending limbs. I. Functional nephron heterogeneity and ADH-stimulated NaCl cotransport. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 241: F412–F431, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hebert SC, Culpepper RM, Andreoli TE. NaCl transport in mouse medullary thick ascending limbs. II. ADH enhancement of transcellular NaCl cotransport; origin of transepithelial voltage. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 241: F432–F442, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrera M, Garvin JL. A high-salt diet stimulates thick ascending limb eNOS expression by raising medullary osmolality and increasing release of endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F58–F64, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00209.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyndman KA, Boesen EI, Elmarakby AA, Brands MW, Huang P, Kohan DE, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Renal collecting duct NOS1 maintains fluid-electrolyte homeostasis and blood pressure. Hypertension 62: 91–98, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahle KT, Macgregor GG, Wilson FH, Van Hoek AN, Brown D, Ardito T, Kashgarian M, Giebisch G, Hebert SC, Boulpaep EL, Lifton RP. Paracellular Cl- permeability is regulated by WNK4 kinase: insight into normal physiology and hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14877–14882, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406172101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimizuka H, Koketsu K. Ion transport through cell membrane. J Theor Biol 6: 290–305, 1964. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Layton AT, Edwards A. Mathematical Modeling in Renal Physiology. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layton HE, Pitman EB, Moore LC. Bifurcation analysis of TGF-mediated oscillations in SNGFR. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F904–F919, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee NP, Cheng CY. Regulation of Sertoli cell tight junction dynamics in the rat testis via the nitric oxide synthase/soluble guanylate cyclase/3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate/protein kinase G signaling pathway: an in vitro study. Endocrinology 144: 3114–3129, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang M, Knox FG. Nitric oxide enhances paracellular permeability of opossum kidney cells. Kidney Int 55: 2215–2223, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu LB, Liu XB, Ma J, Liu YH, Li ZQ, Ma T, Zhao XH, Xi Z, Xue YX. Bradykinin increased the permeability of BTB via NOS/NO/ZONAB-mediating down-regulation of claudin-5 and occludin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 464: 118–125, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu M, Wang X, Wang W. Nitric oxide increases the activity of the apical 70-pS K+ channel in TAL of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F946–F950, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majid DS, Navar LG. Nitric oxide in the control of renal hemodynamics and excretory function. Am J Hypertens 14: 74S–82S, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(01)02073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning RD Jr, Hu L. Nitric oxide regulates renal hemodynamics and urinary sodium excretion in dogs. Hypertension 23: 619–625, 1994. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.23.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merino-Gracia J, Costas-Insua C, Canales MA, Rodríguez-Crespo I. Insights into the C-terminal peptide binding specificity of the PDZ domain of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase: characterization of the interaction with the tight junction protein claudin-3. J Biol Chem 291: 11581–11595, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.724427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadi MT. Overproduction of nitric oxide intensifies brain infarction and cerebrovascular damage through reduction of claudin-5 and ZO-1 expression in striatum of ischemic brain. Pathol Res Pract 212: 959–964, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monzon CM, Garvin JL. Nitric oxide decreases the permselectivity of the paracellular pathway in thick ascending limbs. Hypertension 65: 1245–1250, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Autocrine effects of nitric oxide on HCO(3)(-) transport by rat thick ascending limb. Kidney Int 58: 2069–2074, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2000.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of nephron transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F777–F784, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00334.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. NO decreases thick ascending limb chloride absorption by reducing Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl(-) cotransporter activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F819–F825, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0075.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez-Rojas JM, Kassem KM, Beierwaltes WH, Garvin JL, Herrera M. Nitric oxide produced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase promotes diuresis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R1050–R1055, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00181.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plato CF, Stoos BA, Wang D, Garvin JL. Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits chloride transport in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F159–F163, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tain YL, Leu S, Wu KL, Lee WC, Chan JY. Melatonin prevents maternal fructose intake-induced programmed hypertension in the offspring: roles of nitric oxide and arachidonic acid metabolites. J Pineal Res 57: 80–89, 2014. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trischitta F, Pidalà P, Faggio C. Nitric oxide modulates ionic transport in the isolated intestine of the eel, Anguilla anguilla. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 148: 368–373, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varela M, Herrera M, Garvin JL. Inhibition of Na-K-ATPase in thick ascending limbs by NO depends on O2- and is diminished by a high-salt diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F224–F230, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00427.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei Y, Babilonia E, Pedraza PL, Ferreri NR, Wang WH. Acute application of TNF stimulates apical 70-pS K+ channels in the thick ascending limb of rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F491–F497, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00104.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen H, Watry DD, Marcondes MC, Fox HS. Selective decrease in paracellular conductance of tight junctions: role of the first extracellular domain of claudin-5. Mol Cell Biol 24: 8408–8417, 2004. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8408-8417.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winters CJ, Reeves WB, Andreoli TE. Cl- channels in basolateral renal medullary vesicles: V. Comparison of basolateral mTALH Cl- channels with apical Cl- channels from jejunum and trachea. J Membr Biol 128: 27–39, 1992. doi: 10.1007/BF00231868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu P, Gao Z, Ye S, Qi Z. Nitric oxide inhibits the basolateral 10-pS Cl- channels through cGMP/PKG signaling pathway in the thick ascending limb of C57BL/6 mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F755–F762, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00270.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu AS. Claudins and the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 11–19, 2015. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]