Abstract

Exposure to glucocorticoids in utero is associated with changes in organ function and structure in the adult. The aims of this study were to characterize the effects of antenatal exposure to glucocorticoids on glucose handling and the role of adipose tissue. Pregnant sheep received betamethasone (Beta, 0.17 mg/kg) or vehicle 24 h apart at 80 days of gestation and allowed to deliver at term. At 9 mo, male and female offspring were fed at either 100% of nutritional allowance (lean) or ad libitum for 3 mo (obese). At 1 yr, they were chronically instrumented under general anesthesia. Glucose tolerance was evaluated using a bolus of glucose (0.25 g/kg). Adipose tissue was harvested after death to determine mRNA expression levels of angiotensinogen (AGT), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 1, ACE2, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ). Data are expressed as means ± SE and analyzed by ANOVA. Sex, obesity, and Beta exposure had significant effects on glucose tolerance and mRNA expression. Beta impaired glucose tolerance in lean females but not males. Superimposed obesity worsened the impairment in females and unmasked the defect in males. Beta increased ACE1 mRNA in females and males and AGT in females only (P < 0.05 by three-way ANOVA). Obesity increased AGT in females but had no effect on ACE1 in either males or females. PPAR-γ mRNA exhibited a significant sex (F = 42.8; P < 0.01) and obesity (F = 6.9; P < 0.05) effect and was significantly higher in males (P < 0.01 by three-way ANOVA). We conclude that adipose tissue may play an important role in the sexually dimorphic response to antenatal glucocorticoids.

Keywords: sheep, adipose tissue, antenatal steroids, renin angiotensin system, insulin resistance

on the basis of epidemiological studies, David Barker suggested that an unfavorable intrauterine environment is an important risk factor for developing cardiometabolic disorders, e.g., coronary heart disease, hypertension, and insulin resistance (3, 4). Small for gestational age newborns are at a higher risk for developing impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in adulthood (35–37). In both humans and animals, maternal undernutrition is associated with long-term alterations in glucose/insulin homeostasis (15, 22, 37), and experimental and epidemiological studies suggest that prenatal exposure to elevated glucocorticoid levels is one of the underlying mechanisms for the cardiometabolic alterations seen later in life (1, 23, 49). In sheep, maternal betamethasone (Beta) administration late in gestation increases the insulin response to a glucose load in a pattern resembling the insulin resistance of type 2 diabetes (33). The long-term effects of fetal exposure to glucocorticoids during pregnancy have further clinical relevance, as the administration of synthetic glucocorticoids to women threatened with preterm delivery has become standard obstetric practice (24, 25). A causative role for glucocorticoid exposure in the alteration of glucose handling has been confirmed in several species (8, 18, 27). Antenatal exposure to exogenous steroids triggers programming events that alter glucose tolerance and/or insulin sensitivity in rats (8) and sheep (18). These effects of glucocorticoids appear to be relevant to epidemiology because there are strong correlations between birth weight, plasma cortisol concentrations, and the development of hypertension and type 2 diabetes in humans (37). More important, antenatal exposure to exogenous glucocorticoids, albeit mildly, does alter glucose tolerance in people (9). Cortisol is one of the key hormonal regulators of adipogenesis during fetal life (29); thus excess glucocorticoids is expected to alter the regulation of fetal adipogenesis. All the components of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) as well as the specific receptors, i.e., AT1, AT2, and Mas, are found in adipose tissue and play an important role in the regulation of adipose tissue function (7). Furthermore, studies have shown that angiotensinogen from adipocytes is an important source of substrate for local and systemic production of angiotensin peptides (51) and contributes to the increase in blood pressure associated with adipose tissue dysfunction (30). Altogether these results suggest that the adipose tissue RAS has both local and systemic effects on blood pressure regulation and glucose handling. The aims of the present study were to further characterize the effects of antenatal exposure to glucocorticoids on glucose handling by concentrating on sex differences and the potential role of adipose tissue as a target of fetal programming.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pregnant sheep received two doses of 0.17 mg/kg of a 1:1 mixture of betamethasone acetate and betamethasone phosphate (Celestone Soluspan) or vehicle (11). Intramuscular injections were given 24 h apart at 80 and 81 days of gestation, i.e., 0.55 of gestation (term gestation is 145 days), as more than 50% of pregnancies threatened with premature labor are between 23 and 28 wk (46, 50). After the injections were administered, sheep were maintained with free access to food and water in open pasture. Lambs were weaned at 2 mo of age after spontaneous term delivery and raised in sex-specific enclosures as we have previously described (11, 31). At 9 mo of age, sheep were randomly allocated to be fed ruminant pellets (Rumilab) and hay at either 100% of recommended nutrition allowance or ad libitum for at least 3 mo; in the case of twin pregnancies, only one in the pair of twins was included as study subject. At 12 mo of age, sheep were brought to the laboratory for the in vivo studies. Under isofluorane general anesthesia, sheep were fitted with vascular catheters as previously described (11). We studied 24 males and 19 females in the lean subgroup and 10 males and 16 females in the obese cohort. In all cases, sheep of both sexes were studied with their gonads intact. To remove the potential effects of the cyclical endocrine changes associated with estrous cycle in females, all studies were performed under hormonal conditions mimicking luteal phase by the insertion of a vaginal progesterone implant (Eazi-Breed CIDR, Pfizer Animal Health). Tissues were harvested after euthanasia under deep general anesthesia with isoflurane. All procedures were approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional ACUC.

Blood pressure recording.

The arterial catheter and an open-tip catheter filled with saline were connected to pressure transducers (World Precision Instruments). Pressure was recorded continuously for a minimum of 2 days using Windaq Pro+ data acquisition software (DATAQ Instruments). Pressure recorded from an open-tip catheter was used as a reference to subtract pressure changes related to changes in the animal’s position. One-minute averages were calculated using custom-designed software (Cruncher, Instrument Concepts) (52).

Intravenous glucose tolerance test.

Glucose tolerance status was evaluated using an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT). After at least 12 h of overnight fasting, a bolus of glucose (0.25 g/kg body wt) infused over 2 min was administered intravenously. Blood samples were taken at −3, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 min from the start of the experiment and were used in the analysis. The areas under the curve were calculated using the trapezoidal integration in Microsoft Excel. Glucose concentration was measured by the glucooxidase method and insulin by ELISA (Mercodia Ovine Insulin). For a given sheep, all samples within one set were run at the same time at two dilutions, and samples from a vehicle-treated and a Beta-treated animal were always assayed in the same kit. The intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variance in our hands were 5% and 6%, respectively.

Adipose tissue mRNA expression.

At the time of necropsy, omental and perirenal fat were collected in sterile saline. Adipose tissue fragments were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Analysis of gene expression was performed using real-time qPCR. RNA from adipose tissue was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN) treated with DNase using RNase-Free DNase (QIAGEN). RNA was quantified using spectrophotometry (Nano Drop spectrophotometer, Biolab). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). All cDNA samples were diluted 1:5 before quantitative PCR analysis. TaqMan PCR was performed on the cDNA samples using an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). For each gene tested, PCR was carried out in multiplex mode, with every 20-μl reaction containing 2 μl of cDNA reaction buffer, 1× TaqMan universal PCR master mix, 250 nmol/l of a gene-specific primer, 250 nmol/l of FAM (6-carboxy-fluorescein)-labeled fluorogenic TaqMan probe, and 2.5 U of TaqMan enzymes. The thermal cycling conditions were 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 1 min. GAPDH was used as the reference gene and measured in all samples. Controls were performed by omitting from the reaction either the reverse transcriptase or the RNA. Ovine cDNA sequences found in GenBank for angiotensin-converting enzyme 1 (ACE1) (AJ920033.1), ACE2 (NM_001290107.1), angiotensinogen (D17520.1), proliferator-activated receptor α (PPAR-α) (AY369138.1), and PPAR-γ (AY137204.1) were used for synthesis of forward and reverse PCR primers (See Table 1). Equal amounts of total RNA (100 ng per reaction) were assayed in triplicate for transcripts encoding each gene of interest. For the relative quantification of gene expression, the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method was used.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers used for real-time PCR of mRNA abundance in sheep adipose tissue

| Gene | Sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| ACE | Forward | CTTCCTGCCCTTTGGCTACTT |

| Reverse | CGAAGATACCACCAGTCATAGTTGTAG | |

| Reporter | ACGCCACTGGTCCACC | |

| ACE2 | Forward | ACCTCACTATTTGAAAGCACTTGGT |

| Reverse | GCTTGCTTGAGCAGGAAGTTTATTT | |

| Reporter | TCTGGCACCCGATTTT | |

| Angiotensinogen | Forward | AGGCTTGGGTGGCTGAC |

| Reverse | GAGAATCCCATGTGGGTTGTGA | |

| Reporter | TCAGGCCATCACACCC | |

| PPAR-GAMMA | Forward | CCGCTGACCAAAGCAAAGG |

| Reverse | AGTTCATGTCATAGATAACAAACGGTGAT | |

| Reporter | TTTCCCGTCAAGATCG | |

| PPAR-ALPHA | Forward | TGGACGAATGCCAAGATCTGAAAA |

| Reverse | CTAGGTCATGTTCACACGTAAGGAT | |

| Reporter | TCTGCCTTCAATTTTG | |

| GAPDH | Forward | CTGCCACCCAGAAGACTGT |

| Reverse | CCAGTAGAAGCAGGGATGATGTTC | |

| Reporter | CCCCTCGGCCATCAC |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Plasma leptin.

Plasma leptin concentration was measured by radioimmunoassay (multispecies leptin RIA kit, EMD Millipore) validated for ovine leptin (13, 27). The intraassay and interassay coefficients of variance in our hands were 3% and 7%, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE and were analyzed by either two or three-way ANOVA. Blood pressure, computed as the mean of 2,400 1-min pressure averages over 2 days (52), and body composition were analyzed by three-way ANOVA (factors included in the analysis were treatment, weight status, and sex). Birth outcomes (birth weight and gestational length) were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using treatment (Beta/vehicle) and sex for each subset of weight status. For IVGTT data, we used repeated-measures two-way ANOVA to account for treatment effect (Beta vs. control) and multiple sampling within sex. RNA data were analyzed using two- or three-way ANOVA to account for sex, treatment, and modifier (lean or obese) using the statistics module in SigmaPlot 13 (Systat Software). The Holm-Sidak test was used for post hoc multiple comparisons. To determine treatment differences on the slopes of the linear regression analysis of plasma leptin concentration, we used the P value of the Z score of the differences (34).

RESULTS

Cohort characteristics and basal cardiovascular function.

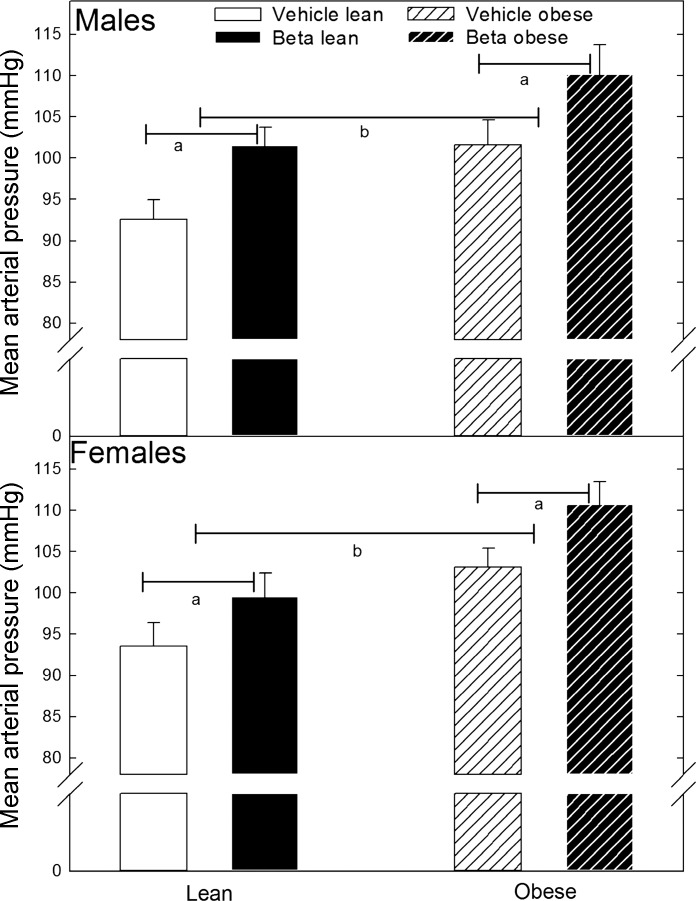

By design, animals in the obese group were expected to have a 50% increase in body weight following the ad libitum feeding period. Whereas female obese sheep were on average 60% heavier than their lean counterparts, males were only 40% heavier than the sheep in the respective lean group (Table 2). In addition, there were no significant differences in birth weight, gestational length, or the number of twins between and within treatment groups (Table 2). In all cases, only one in the pair of twins was included in this study. There were no significant effects of Beta in adult body weight within males or females in either the lean or obese cohorts (Table 2). As a positive control for the programming effects of Beta (11), before any experimental manipulation, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP; Fig. 1) was shown to be significantly higher in Beta-treated sheep (females 94 ± 2.8 vs. 100 ± 2.8 mmHg; males 93 ± 2.4 vs. 102 ± 2.2 mmHg; vehicle vs. Beta respectively; F = 7.8 P < 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA). As expected, obesity significantly increased MAP (F = 17.9 P < 0.001 overall obesity effect, Fig. 1). Notwithstanding, we did not find a significant interaction between obesity and sex or obesity and Beta treatment. Compared with males in their respective treatment group, female MAP was not statistically different from that of the males (Fig. 1). Adult sheep exhibited a significantly different sex-dependent adipose tissue distribution independent of body weight and glucocorticoid exposure (Table 2). Whereas no significant Beta effect was observed in omental fat tissue mass in either the lean or obese sheep, expressed as a percentage of body weight, female obese sheep in both treatment groups had more omental fat compared with obese males (P < 0.05 by t-test). In contrast, a sex difference in perirenal adipose tissue distribution was apparent both as absolute weight and as a percentage of body weight in the lean and obese groups (Table 2) (P < 0.05 by t-test).

Table 2.

Gestational age, birth weight, adult body weight, and adipose tissue weight in lean and obese adult sheep treated prenatally with glucocorticoids

| Female |

Male |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle |

Betamethasone |

Vehicle |

Betamethasone |

|||||

| Lean | Obese | Lean | Obese | Lean | Obese | Lean | Obese | |

| Number | 8 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 13 | 6 |

| Gestation, days | ||||||||

| All | 145.0 ± 1.0 | 143.0 ± 2.0 | 145.0 ± 1.1 | 146.0 ± 0.4 | 145.0 ± 1.3 | 144.0 ± 0.5 | 145.0 ± 0.5 | 144.0 ± 0.5 |

| Singleton | 147.0 ± 0.5 | 147.0 ± 0.5 | 146.0 ± 0.7 | 145.0 ± 0.5 | 145.0 ± 1.1 | 146.0 ± 1.0 | 145.0 ± 1.0 | 145.0 ± 1.0 |

| Twin | 144.0 ± 1.0 | 143.0 ± 2.2 | 144.0 ± 1.7 | 147.0 ± 0.4 | 145.0 ± 0.6 | 144.0 ± 0.6 | 145.0 ± 0.6 | 144.0 ± 0.6 |

| Birth weight, kg | ||||||||

| All | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

| Singleton | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.6 |

| Twin | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 |

| Body weight, kg | 43.0 ± 2.5† | 72.0 ± 1.9* | 45.0 ± 3.6† | 74.0 ± 1.9* | 54.0 ± 2.4 | 78.0 ± 1.7* | 54.0 ± 2.1 | 76.0 ± 4.0* |

| Omental fat weight, kg | 0.7 ± 0.12 | 2.3 ± 0.18* | 1.1 ± 0.11 | 2.7 ± 0.17* | 0.7 ± 0.08 | 2.0 ± 0.30* | 0.6 ± 0.08 | 1.7 ± 0.04* |

| Perirenal fat weight, kg | 0.5 ± 0.10† | 1.9 ± 0.18*† | 0.6 ± 0.07† | 2.1 ± 0.13*† | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 1.1 ± 0.28* | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.8 ± 0.20* |

| Omental fat, % | 1.7 ± 0.18† | 3.2 ± 0.23*† | 2.3 ± 0.18† | 3.7 ± 0.21*† | 1.1 ± 0.13 | 2.6 ± 0.35* | 1.1 ± 0.12 | 2.2 ± 0.14* |

| Perirenal fat, % | 1.1 ± 0.16† | 2.6 ± 0.23*† | 1.2 ± 0.12† | 2.8 ± 0.17*† | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 1.5 ± 0.34* | 0.6 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.28* |

Values are means ± SE.

P < 0.05 lean vs. obese within same treatment;

P < 0.05 female vs. male within same treatment.

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial blood pressure in male and female adult sheep treated prenatally with either vehicle or betamethasone (Beta). Adult sheep were fed either 100% of nutritional requirement (lean) or ad libitum (obese). Male (lean vehicle n = 11; lean Beta n = 13; obese vehicle n = 6; obese Beta n = 4). Female (lean vehicle n = 8; lean Beta n = 11; obese vehicle n = 8; obese Beta n = 8). Statistically significantly different by ANOVA: aP < 0.05 Beta vs. vehicle; blean vs. obese.

Glucose tolerance.

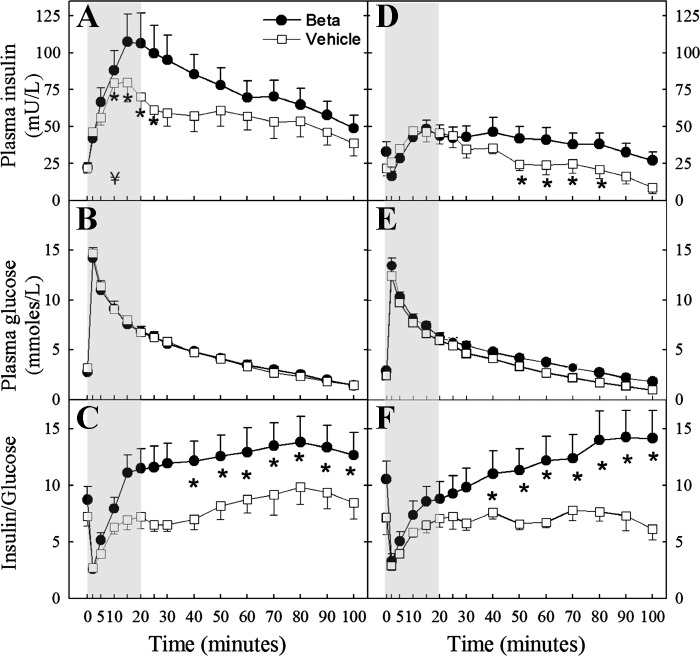

In animals exposed to antenatal glucocorticoids and fed 100% of the recommended nutritional allowance, there was a significant sex-dependent effect on glucose handling. Data from singletons and twins were pooled, as no statistical differences were found in outcomes when compared in each treatment group. Despite the trend for fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations to be higher in exposed animals, no significant differences were observed (Table 3). In contrast, the plasma insulin response to an acute glucose load was significantly higher in lean Beta-treated females (F = 5.02; P < 0.05; Fig. 2A) but not in Beta-treated males (Fig. 2D). Similarly, the insulin-to-glucose ratio was significantly higher in Beta-treated females (F = 4.3 P < 0.05; Fig. 2C) but not in Beta-treated males (Fig. 2F). The plasma insulin concentration assessed as the area under the curve between time 0 and 20 min (AUC 0–20) was also significantly higher in Beta-treated females; 464.0 ± 44.5 vs. 885.0 ± 135.3 mU·l−1·min−1, vehicle-treated and Beta-treated respectively (P < 0.05 by 2-sample t-test). A similar statistically significant effect of Beta was observed in the AUC 0–20 for the insulin-to-glucose ratio (Fig. 2, C and F).

Table 3.

Fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentration in female and male sheep exposed antenatally to either vehicle or betamethasone

| Vehicle | Beta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean | Obese | Lean | Obese | |

| Females | ||||

| Glucose, mmol/l | 2.0 ± 0.40 | 3.1 ± 0.39 | 2.7 ± 0.51 | 4.1 ± 0.68 |

| Insulin, mU/ml | 8.0 ± 1.21 | 21.8 ± 3.19 | 16.2 ± 5.17 | 22.3 ± 3.11 |

| Males | ||||

| Glucose, mml/l | 1.7 ± 0.19 | 3.2 ± 0.40 | 1.4 ± 0.30 | 3.0 ± 0.50 |

| Insulin, mU/ml | 8.2 ± 0.95 | 21.5 ± 5.61 | 7.4 ± 1.46 | 29.8 ± 7.01 |

Values are means ± SE. Fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations were unaffected by sex, and interactions between sex and betamethasone or obesity were nonsignificant. Therefore, data were combined for males and females.

Fig. 2.

Plasma insulin, glucose, and insulin:glucose (I/G) ratio after a bolus injection of glucose (0.25 g/kg) in adult female (A–C) and male (D–F) sheep treated prenatally with either vehicle or Beta fed at 100% of the nutritional requirements (female: vehicle n = 8; Beta n = 11; male: vehicle n = 11; Beta n = 13). A significant Beta effect was observed in the insulin response in females only (2-way repeated-measures ANOVA). Significant differences for individual time points are indicated by *P < 0.05 using Holm-Sidak method. A significant difference in the area under the curve between time 0 and 20 min (AUC0–20) (shaded area) for insulin and I/G was present in females only (¥). Beta effect on AUC0–20 by t-test was P < 0.05.

Superimposed obesity, achieved by allowing sheep free access to standard ruminant feed, significantly increased the insulin response to the glucose load in both sexes and in both vehicle-exposed and Beta-exposed treatment groups. Obesity, not only significantly worsened the preexisting higher insulin response in Beta-exposed females (Fig. 3A), but it also unmasked a Beta effect on the plasma insulin response to a glucose load in males (Fig. 3D). A significant Beta effect was also observed on the insulin-to-glucose ratio, suggesting the development of insulin resistance (Fig. 5) in the obese male offspring. Obesity increased the AUC 0–20 from 464.0 ± 44.5 to 954 ± 120.3 mU·l−1·min−1 in vehicle-treated and from 885.0 ± 135.3 to 1214.0 ± 201.4 mU·l−1·min−1 in Beta-treated females (P < 0.05 lean vs. obese). In the case of males, the effect of superimposed obesity was observed in the latter portion of the IVGTT curve Fig. 3D; with the AUC 20–100 for insulin concentration increasing from 1212.0 ± 210.1 mU·l−1·min−1 to 1852.0 ± 407.1 mU·l−1·min−1 and from 974.0 ± 281.2 mU·l−1·min−1 to 2744.0 ± 508.1 mU·l−1·min−1 in vehicle-treated and Beta-treated animals, respectively (P < 0.05 lean vs. obese by 2-sample t-test). A similar statistically significant effect of obesity was observed in the AUC 20–100 for the insulin-to-glucose ratio (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Plasma insulin, glucose, and I/G ratio after a bolus injection of glucose (0.25 g/kg) in obese adult female (A–C) and male (D–F). Sheep were treated prenatally with either vehicle or Beta and fed ad libitum (female: vehicle n = 8; Beta n = 8; male: vehicle n = 4; Beta n = 6). A significant Beta effect was observed in the insulin response and the I/G ratio in both females and males (2-way repeated-measures ANOVA). Significant differences for individual time points are indicated by *P < 0.05 using Holm-Sidak method. A significant difference in the AUC0–20 shaded area (¥) for insulin was present in females only. Beta effect by t-test was P < 0.05.

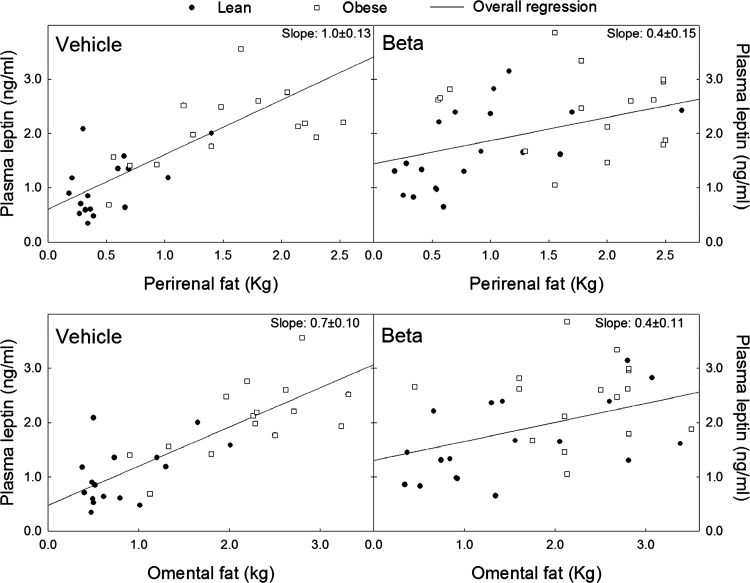

Fig. 5.

Linear regression analysis of plasma leptin levels and perirenal (top) and omental (bottom) fat weight in adult male and female sheep treated prenatally with either vehicle or Beta fed either 100% of their nutritional requirements (lean, vehicle n = 18, Beta n = 17) or ad libitum (obese, vehicle n = 15, Beta n = 25). Beta significantly altered the slope of the relationship between adipose tissue weight and plasma leptin. Z = 2.87 (P < 0.003) and 2.43 (P < 0.008) vehicle vs. Beta for perirenal and omental fat, respectively.

Plasma leptin concentration.

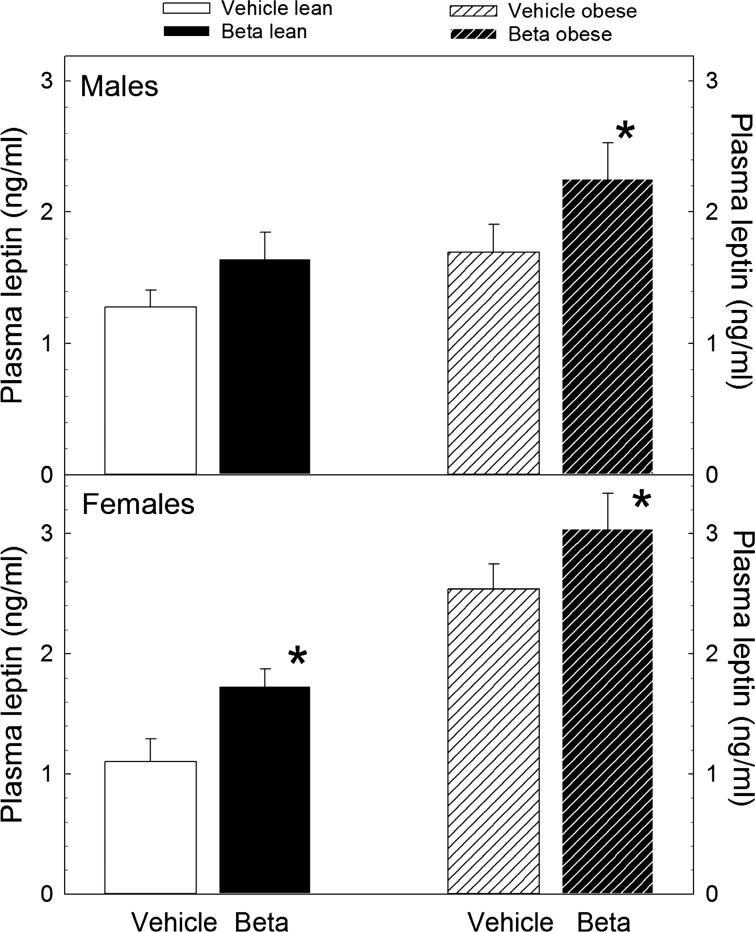

With the exception of lean males, a statistically significant elevation in plasma leptin concentration was present in Beta-exposed sheep (Fig. 4; P < 0.05 by ANOVA). Notwithstanding, there was a trend for a Beta effect in lean males. As expected, superimposed obesity was associated with a significant increase in plasma leptin concentration in both treatment groups and both sexes. However, we did not observe an interaction between sex and treatment or obesity and treatment. Linear regression analysis of the relationship between adiposity, assessed by total body weight, revealed that the positive relationship between plasma leptin concentration and total body weight was lost in Beta-exposed lean females but not in males as indicated by the absence of a significant linear fit and the statistically significant difference in the calculated slope of the regression (Table 4). When lean and obese animals of both sexes were analyzed as a group, we found that the significant linear correlation between plasma leptin concentration and omental fat weight and between plasma leptin concentration and perirenal fat weight is lost in Beta-exposed animals as indicated by the statistically significant difference in the calculated slopes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Plasma leptin concentration in adult male and female sheep treated prenatally with either vehicle or Beta fed either 100% of their nutritional requirements (lean) or ad libitum (obese). *P < 0.01 by 2-way ANOVA. Male vehicle n = 4 obese, n = 11 lean; male Beta n = 6 obese, n = 13 lean. Female vehicle n = 8 obese, n = 8 lean; female Beta n = 8 obese, n = 11 lean.

Table 4.

Statistics of plasma leptin over perirenal, omental, and body weight in lean female and male sheep exposed antenatally to either vehicle or betamethasone

| Vehicle |

Beta |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | SE | F | P | R2 | Slope | SE | F | P | R2 | Z | P | |

| Female | ||||||||||||

| PR | 0.820 | 0.487 | 2.800 | 0.130 | 0.490 | 0.680 | 0.346 | 3.900 | 0.070 | 0.240 | 0.220 | NS |

| OM | 0.790 | 0.404 | 3.800 | 0.090 | 0.320 | 0.120 | 0.264 | 0.200 | 0.650 | 0.010 | 1.370 | 0.085 |

| Body Wt, kg | 0.060 | 0.019 | 9.700 | 0.010 | 0.550 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.800 | 0.390 | 0.040 | 2.420 | 0.007 |

| Male | ||||||||||||

| PR | 1.230 | 0.385 | 10.300 | 0.020 | 0.690 | 0.660 | 0.342 | 3.800 | 0.090 | 0.350 | 1.110 | NS |

| OM | 0.580 | 0.120 | 22.800 | 0.010 | 0.790 | 0.410 | 0.156 | 7.000 | 0.030 | 0.490 | 0.820 | NS |

| Body Wt | 0.040 | 0.011 | 15.300 | 0.010 | 0.710 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 6.200 | 0.030 | 0.340 | 1.230 | NS |

F, F statistic for the regression; P, regression and slope P value; R2, regression coefficient; Z, Z statistic for the comparison of slopes (vehicle vs. betamethasone, Beta); P, significance of the Z value; PR, perirenal; OM, omental.

Adipose tissue mRNA expression.

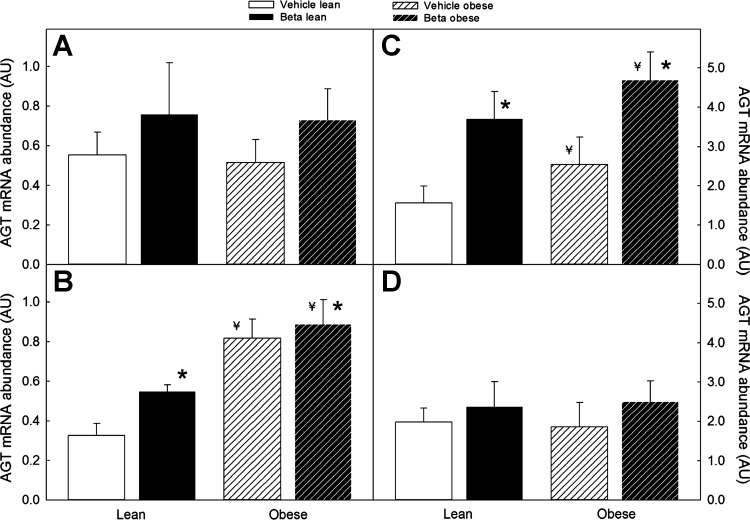

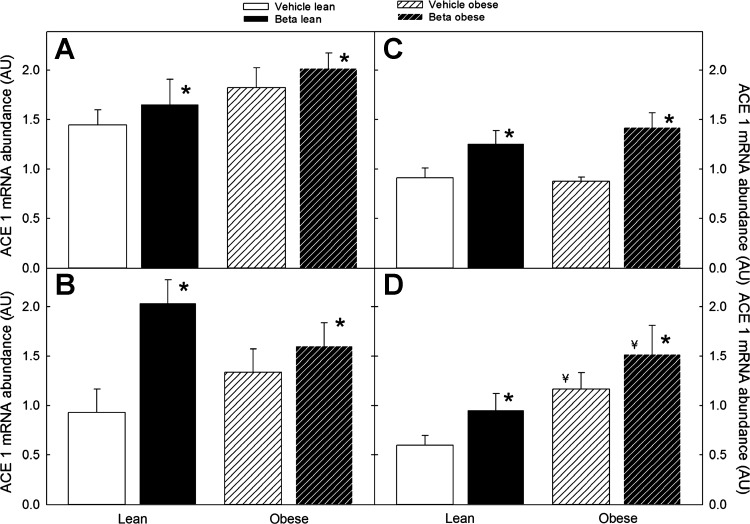

The effect of Beta exposure on adipose tissue expression of angiotensinogen mRNA was sex/site dependent. In females, a significant increase in angiotensin expression was observed in omental fat, whereas, in males, a significant effect of Beta exposure was evident in the perirenal fat depot (Fig. 6; P < 0.05 by ANOVA). Similar to the Beta effect, superimposed obesity significantly increased omental fat angiotensinogen mRNA expression in females and in perirenal fat in males (Fig. 6; P < 0.05 by ANOVA). In the case of ACE1, Beta exposure increased ACE1 mRNA expression in the two fat depots in both males and females; with the effect of superimposed obesity on ACE1 expression being evident only in female perirenal fat (Fig. 7; P < 0.05 by 3-way ANOVA).

Fig. 6.

Angiotensinogen (AGT) mRNA expression in omental (left) and perirenal (right) adipose tissue of male (A and C) and female (B and D) sheep treated prenatally with either vehicle or Beta. Sheep were fed either 100% of their nutritional requirements (lean) or ad libitum (obese). A significant overall Beta effect was present in omental AGT mRNA expression in females (vehicle n = 6, Beta n = 6) and in perirenal fat in males (vehicle n = 8, Beta n = 7) (*P < 0.05 by 3-way ANOVA). An overall obesity effect was observed in omental AGT mRNA expression in female (B) and perirenal AGT mRNA in males (C); ¥P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

Fig. 7.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 1 (ACE1) mRNA expression in omental (left) and perirenal (right) adipose tissue of male (A and C) and female (B and D) sheep treated prenatally with either vehicle or Beta. Sheep were fed either 100% of their nutritional requirements (lean) or ad libitum (obese). A significant overall Beta effect on ACE1 mRNA expression was present in omental (A and C) and perirenal (B and D) fat in males and females (n = 6 each group, *P < 0.05 by 3-way ANOVA). An overall obesity effect was present in female perirenal ACE1 mRNA (¥P < 0.05).

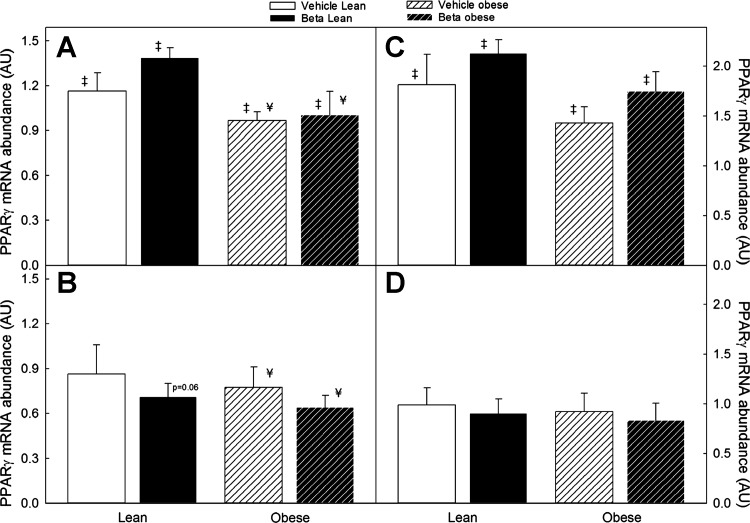

As shown in Fig. 8A, we found a significant sex difference in omental fat PPAR-γ mRNA expression with males expressing higher levels compared with females (Fig. 8B) in the same treatment group (F = 18.8; P < 0.001). We also found a significant decrease in PPAR-γ mRNA in obese males fed ad libitum (F = 6.5; P < 0.01). However, there was no statistically significant Beta effect. In females, a sex × treatment interaction, suggesting a Beta effect, was borderline significant (Fig. 8B; F = 3.8; P = 0.06). Superimposed obesity was also associated with a small but significant decrease in PPAR-γ expression in males and females in each of the treatment groups (Fig. 8; P < 0.05 by 3-way ANOVA). In perirenal fat, there was also a significantly higher expression in males compared with females in the same treatment group (F = 31.2, P < 0.01; Fig. 8), but we did not observe either a Beta or obesity effect on PPAR-γ expression in this fat depot. Adiponectin, AT1, AT2, ACE2, and PPAR-α mRNA expression did not exhibit significant differences associated with treatment, sex, or obesity status (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ) mRNA expression in omental (left) and perirenal (right) adipose tissue of male (A and C) and female (B and D) sheep treated prenatally with either vehicle or Beta. Sheep were fed either 100% of their nutritional requirements (lean) or ad libitum (obese). Compared with females (B and D), male sheep (A and C) had significantly higher PPAR-γ mRNA expression across body weight and treatment (n = 6 each group, ‡P < 0.05 by 2-way ANOVA). Superimposed obesity significantly decreased PPAR-γ mRNA expression in males and females in both treatment groups (¥P < 0.05 by ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological and experimental evidence supports a “fetal programming” mechanism for the development of a variety of diseases in adults. There is general agreement that exposure to abnormally high levels of glucocorticoids is one of the mechanisms by which an unfavorable intrauterine environment increases the risk for manifesting signs of disease in the adult. The results of this study are important as we provide evidence to show that 1) antenatal Beta exposure programs the insulin response to a standardized glucose load in adult animals, 2) the magnitude of the Beta effect on glucose tolerance is sex dependent, and 3) superimposed obesity unmasks a latent abnormality in glucose handling in the steroid-exposed male offspring. The present study also confirms, once again, that antenatal exposure to clinically relevant doses of Beta is associated with alterations in adult sheep physiology consistent with the concept of fetal programming, i.e., blood pressure elevation, abnormal glucose handling, and abnormal leptin secretion. Although our findings regarding glucose tolerance and potentially insulin resistance are at variance with previous studies in sheep, timing, dose, type, and route of the glucocorticoid administered need to be considered to reconcile the findings. The reports range from no effect on glucose tolerance with maternal intravenous administration of dexamethasone at ages 27 and 64 days of gestation (16) to reduced insulin secretion after dexamethasone exposure at 103 days of gestation (26). In contrast, with the use of an approach similar to ours, single maternal administration of Beta at 104 days of gestation was associated with a statistically significant increase in the insulin response to a glucose load (41). The main difference between the two synthetic steroids is their half-life. In the study of Long et al. (26), dexamethasone was used at a third of the clinically recommended dose and because of its shorter half-life may not have affected adipose tissue development. However, it may have affected pancreatic development resulting in low insulin secretion capacity. In sheep, as in humans, fetal fat develops mid to late gestation (43); thus early administration, as in the study of Gatford et al. (16), is not expected to have a significant effect on adipose tissue development. We believe our findings have direct clinical relevance because 30–50% of women diagnosed as being in preterm labor are treated with glucocorticoids at gestational ages earlier than 28 wk of gestation (46, 50) and remain undelivered after 2 wk (32). Furthermore, about a third of them (10–15%) will in fact deliver at term (32), with many receiving additional courses of antenatal glucocorticoids (2). Our results show that exposure to a single course of Beta equivalent to that used in women threatened to deliver prematurely is associated with alterations in glucose handling in the adult. Importantly, evidence of metabolic fetal programming has also been reported following antenatal steroid administration in humans. Adult offspring of pregnant women treated with antenatal glucocorticoids at 26–34 wk of gestation studied at 30 yr of age had statistically significant higher insulin levels at 30 min following an oral glucose tolerance test. Furthermore, the differences were more pronounced in women compared with men (9). Although sex differences in outcome measures is a common feature of data generated in animal models of fetal programming, little is known regarding the exact mechanism. Our data suggest that intrinsic sex differences in adipose tissue abundance and function contribute to the sex-dependent effect of antenatal steroid exposure. We found that, across treatments, i.e., vehicle, Beta, and obesity, visceral adipose tissue mass either in absolute or relative terms was higher in females. Although there is evidence for significant sex-related differences in distribution and total adipose tissue in early development (6, 10), marked regional differences in adipose tissue distribution in males and females continue to develop later in life under the control of sex hormones. Therefore, with the data at hand, we cannot rule out a role for gonadal steroids on the differences observed.

Adipose tissue can be found in the human fetus after the 14th week of gestation and amounts to ~13% of the newborn’s body mass at birth. In sheep, as in humans, fetal fat deposition occurs during the last third of gestation (43). Both humans and sheep are precocial thermoregulators; thus adipose tissue development is geared toward maximizing the abundance of uncoupling protein 1. Throughout the last third of gestation, a steady rise in plasma cortisol is known to play a pivotal role in fetal adipogenesis (44). Notwithstanding, our data suggest that untimely exposure to high concentrations of glucocorticoids has a permanent effect on adipose tissue function that in males becomes evident in the obese state. In sheep visceral adipose tissue, mRNA abundance for the glucocorticoid receptor and 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11-βHSD1) increase and 11-βHSD2 mRNA abundance decreases with postnatal age (17). Interestingly, the expression profile of these modulators of glucocorticoid function is different in visceral adipose tissue compared with that of other tissues, lending support to the potential importance of untimely exposure to glucocorticoids in altering fat differentiation, development, and function. Fetal adipose tissue has also been shown to have a sex-dependent response to exogenous glucocorticoids. Dexamethasone administered in clinically relevant doses to near-term sheep fetuses was associated with an increase in adiposity in adult females but not in males, an effect not associated with alteration in either size at birth or postnatal growth velocity (5).

The significant obesity-associated decrease in PPAR-γ mRNA expression across all treatment groups is in keeping with the view that inhibition of PPAR-γ function and/or expression is a central component of the insulin resistance associated with obesity (20, 45). Activation of PPAR-γ in adipocytes and preadipocytes results in more differentiated adipocytes with higher capacity to accumulate fat and less secretion of TNF-α and resistin (20, 42). Also, a decrease in PPAR-γ mRNA expression in adipose tissue is associated with a decrease in both adipose tissue and systemic insulin sensitivity, particularly during periods of high caloric intake (20, 42). In addition to the anatomical differences in adipose tissue distribution between sexes, functional differences may also be important contributors to the relative protection to the programming effects of Beta exposure in males. In addition to the significant sex difference in PPAR-γ mRNA expression favoring males, circulating estrogen levels may also play an important role. The estrogen receptor subtype β (ERβ) has a negative regulatory effect on insulin signaling and glucose metabolism by impairing PPAR-γ function as shown in mice with ERβ gene deletion resulting in better insulin sensitivity (14). In humans, the ERα-to-ERβ ratio in adipose tissue has been shown to be associated with obesity and leptin production in omental adipose tissue; a predominance of ERβ in omental fat was associated with higher adiposity and leptin production (40).

Our findings of increased expression of ACE1 mRNA and increased ACE1-to-ACE2 ratio in adipose tissue are consistent with the abnormalities in the RAS we have also observed in kidney cortex, brain stem, and in circulation in this animal model (19, 28). All components of the RAS, including the ANG II receptors AT1 and AT2 and also the ANG1-7 receptor (Mas), are known to be expressed in white adipose tissue where the system has been shown to regulate adipose tissue differentiation, growth, and metabolism (38). Although activation of a local adipose tissue RAS is known to play a major role in obesity-associated insulin resistance and hypertension, the specific physiological role of each receptor subtype in adipocytes remains unclear. The predicted net result of this imbalance in enzyme mRNA expression is high ANG II (39) and low ANG1-7 tissue levels (48). In addition to an imbalance in the ACE1-to-ACE2 ratio, Beta-exposed females showed higher levels of angiotensinogen mRNA, which, by providing extra substrate for renin and thus higher ANG II synthesis, may contribute to the increased leptin secretion (21).

In summary, our data show that both anatomical and functional differences in adipose tissue play an important role in the sexually dimorphic response to antenatal glucocorticoids. We also provide evidence suggesting a mechanistic involvement of the local adipose tissue RAS, in particular, an imbalance between the ANG II/AT1 and the ANG1-7/Mas signaling pathways. Notwithstanding, further studies are required to establish the intimate mechanism linking adipose tissue RAS and the observed alterations in glucose tolerance. Finally, we showed that obesity, acting as a second hit, exposes the latent programming effects of antenatal glucocorticoid exposure on glucose handling in males.

Perspectives and Significance

Administration of synthetic glucocorticoids in women threatened with premature labor remains the only effective treatment to decrease the incidence of acute respiratory distress in newborns of less than 34 wk of gestation, and, of those, >50% are treated at a time of rapid fetal growth and differentiation. We provide evidence to support a potential mechanism to explain the development of abnormal glucose tolerance following antenatal glucocorticoids.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-68728 and HD-04784.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.A.M., J.Z., W.J.S., and M.K. performed experiments; G.A.M. and J.Z. analyzed data; G.A.M. and J.P.F. interpreted results of experiments; G.A.M., J.Z., W.J.S., and J.P.F. edited and revised manuscript; G.A.M. and J.P.F. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almond K, Bikker P, Lomax M, Symonds ME, Mostyn A. The influence of maternal protein nutrition on offspring development and metabolism: the role of glucocorticoids. Proc Nutr Soc 71: 198–203, 2012. doi: 10.1017/S0029665111003363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks BA, Cnaan A, Morgan MA, Parer JT, Merrill JD, Ballard PL, Ballard RA; North American Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Study Group . Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids and outcome of premature neonates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181: 709–717, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70517-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 301: 1111, 1990. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, Kuh D, Wadsworth ME. Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 298: 564–567, 1989. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6673.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry MJ, Jaquiery AL, Oliver MH, Harding JE, Bloomfield FH. Antenatal corticosteroid exposure at term increases adult adiposity: an experimental study in sheep. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 92: 862–865, 2013. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butte NF, Hopkinson JM, Wong WW, Smith EO, Ellis KJ. Body composition during the first 2 years of life: an updated reference. Pediatr Res 47: 578–585, 2000. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassis LA, Police SB, Yiannikouris F, Thatcher SE. Local adipose tissue renin-angiotensin system. Curr Hypertens Rep 10: 93–98, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleasby ME, Kelly PA, Walker BR, Seckl JR. Programming of rat muscle and fat metabolism by in utero overexposure to glucocorticoids. Endocrinology 144: 999–1007, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalziel SR, Walker NK, Parag V, Mantell C, Rea HH, Rodgers A, Harding JE. Cardiovascular risk factors after antenatal exposure to betamethasone: 30-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365: 1856–1862, 2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66617-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fields DA, Krishnan S, Wisniewski AB. Sex differences in body composition early in life. Gend Med 6: 369–375, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueroa JP, Rose JC, Massmann GA, Zhang J, Acuña G. Alterations in fetal kidney development and elevations in arterial blood pressure in young adult sheep after clinical doses of antenatal glucocorticoids. Pediatr Res 58: 510–515, 2005. 10.1203/01.PDR.0000179410.57947.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford SP, Hess BW, Schwope MM, Nijland MJ, Gilbert JS, Vonnahme KA, Means WJ, Han H, Nathanielsz PW. Maternal undernutrition during early to mid-gestation in the ewe results in altered growth, adiposity, and glucose tolerance in male offspring. J Anim Sci 85: 1285–1294, 2007. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foryst-Ludwig A, Clemenz M, Hohmann S, Hartge M, Sprang C, Frost N, Krikov M, Bhanot S, Barros R, Morani A, Gustafsson JA, Unger T, Kintscher U. Metabolic actions of estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) are mediated by a negative cross-talk with PPARgamma. PLoS Genet 4: e1000108, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner DS, Tingey K, Van Bon BW, Ozanne SE, Wilson V, Dandrea J, Keisler DH, Stephenson T, Symonds ME. Programming of glucose-insulin metabolism in adult sheep after maternal undernutrition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R947–R954, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00120.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatford KL, Wintour EM, De Blasio MJ, Owens JA, Dodic M. Differential timing for programming of glucose homoeostasis, sensitivity to insulin and blood pressure by in utero exposure to dexamethasone in sheep. Clin Sci (Lond) 98: 553–560, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gnanalingham MG, Mostyn A, Symonds ME, Stephenson T. Ontogeny and nutritional programming of adiposity in sheep: potential role of glucocorticoid action and uncoupling protein-2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1407–R1415, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00375.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray S, Stonestreet BS, Thamotharan S, Sadowska GB, Daood M, Watchko J, Devaskar SU. Skeletal muscle glucose transporter protein responses to antenatal glucocorticoids in the ovine fetus. J Endocrinol 189: 219–229, 2006. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gwathmey TM, Shaltout HA, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Glucocorticoid-induced fetal programming alters the functional complement of angiotensin receptor subtypes within the kidney. Hypertension 57: 620–626, 2011. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He W, Barak Y, Hevener A, Olson P, Liao D, Le J, Nelson M, Ong E, Olefsky JM, Evans RM. Adipose-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma knockout causes insulin resistance in fat and liver but not in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15712–15717, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536828100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Whelan J, Claycombe K, Reath DB, Moustaid-Moussa N. Angiotensin II increases leptin secretion by 3T3-L1 and human adipocytes via a prostaglandin-independent mechanism. J Nutr 132: 1135–1140, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kind KL, Clifton PM, Grant PA, Owens PC, Sohlstrom A, Roberts CT, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Effect of maternal feed restriction during pregnancy on glucose tolerance in the adult guinea pig. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R140–R152, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00587.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langley-Evans SC. Hypertension induced by foetal exposure to a maternal low-protein diet, in the rat, is prevented by pharmacological blockade of maternal glucocorticoid synthesis. J Hypertens 15: 537–544, 1997. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leviton LC, Goldenberg RL, Baker CS, Schwartz RM, Freda MC, Fish LJ, Cliver SP, Rouse DJ, Chazotte C, Merkatz IR, Raczynski JM. Methods to encourage the use of antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 281: 46–52, 1999. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liggins GC, Howie RN. A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. Pediatrics 50: 515–525, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long NM, Shasa DR, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW. Growth and insulin dynamics in two generations of female offspring of mothers receiving a single course of synthetic glucocorticoids. Am J Obstet Gynecol 207: 203.e1–203.e8, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long NM, Smith DT, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW. Elevated glucocorticoids during ovine pregnancy increase appetite and produce glucose dysregulation and adiposity in their granddaughters in response to ad libitum feeding at 1 year of age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 209: 353.e1–353.e9, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall AC, Shaltout HA, Pirro NT, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Antenatal betamethasone exposure is associated with lower ANG-(1–7) and increased ACE in the CSF of adult sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R679–R688, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00321.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin RJ, Hausman GJ, Hausman DB. Regulation of adipose cell development in utero. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 219: 200–210, 1998. doi: 10.3181/00379727-219-44333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massiéra F, Bloch-Faure M, Ceiler D, Murakami K, Fukamizu A, Gasc JM, Quignard-Boulange A, Negrel R, Ailhaud G, Seydoux J, Meneton P, Teboul M. Adipose angiotensinogen is involved in adipose tissue growth and blood pressure regulation. FASEB J 15: 2727–2729, 2001. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0457fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massmann GA, Zhang J, Rose JC, Figueroa JP. Acute and long-term effects of clinical doses of antenatal glucocorticoids in the developing fetal sheep kidney. J Soc Gynecol Investig 13: 174–180, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLaughlin KJ, Crowther CA, Walker N, Harding JE. Effects of a single course of corticosteroids given more than 7 days before birth: a systematic review. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol 43: 101–106, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8666.2003.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss TJ, Sloboda DM, Gurrin LC, Harding R, Challis JR, Newnham JP. Programming effects in sheep of prenatal growth restriction and glucocorticoid exposure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R960–R970, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH. Indicator variables. In: Applied Linear Regression Models, edited by Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH. Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1983, p. 328–376. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips DI, Barker DJ, Fall CH, Seckl JR, Whorwood CB, Wood PJ, Walker BR. Elevated plasma cortisol concentrations: a link between low birth weight and the insulin resistance syndrome? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 757–760, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phipps K, Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Clark PM. Fetal growth and impaired glucose tolerance in men and women. Diabetologia 36: 225–228, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00399954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravelli AC, van der Meulen JH, Michels RP, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Hales CN, Bleker OP. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. Lancet 351: 173–177, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubio-Ruíz ME, Del Valle-Mondragón L, Castrejón-Tellez V, Carreón-Torres E, Díaz-Díaz E, Guarner-Lans V. Angiotensin II and 1-7 during aging in Metabolic Syndrome rats. Expression of AT1, AT2 and Mas receptors in abdominal white adipose tissue. Peptides 57: 101–108, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaltout HA, Westwood BM, Averill DB, Ferrario CM, Figueroa JP, Diz DI, Rose JC, Chappell MC. Angiotensin metabolism in renal proximal tubules, urine, and serum of sheep: evidence for ACE2-dependent processing of angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F82–F91, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00139.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin JH, Hur JY, Seo HS, Jeong YA, Lee JK, Oh MJ, Kim T, Saw HS, Kim SH. The ratio of estrogen receptor alpha to estrogen receptor beta in adipose tissue is associated with leptin production and obesity. Steroids 72: 592–599, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sloboda DM, Moss TJ, Li S, Doherty DA, Nitsos I, Challis JR, Newnham JP. Hepatic glucose regulation and metabolism in adult sheep: effects of prenatal betamethasone. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289: E721–E728, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugii S, Olson P, Sears DD, Saberi M, Atkins AR, Barish GD, Hong SH, Castro GL, Yin YQ, Nelson MC, Hsiao G, Greaves DR, Downes M, Yu RT, Olefsky JM, Evans RM. PPARgamma activation in adipocytes is sufficient for systemic insulin sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 22504–22509, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912487106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Symonds ME, Bird JA, Clarke L, Gate JJ, Lomax MA. Nutrition, temperature and homeostasis during perinatal development. Exp Physiol 80: 907–940, 1995. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Symonds ME, Mostyn A, Pearce S, Budge H, Stephenson T. Endocrine and nutritional regulation of fetal adipose tissue development. J Endocrinol 179: 293–299, 2003. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1790293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tham DM, Martin-McNulty B, Wang YX, Wilson DW, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, Dole W, Rutledge JC. Angiotensin II is associated with activation of NF-kappaB-mediated genes and downregulation of PPARs. Physiol Genomics 11: 21–30, 2002. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00062.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Mele L, Johnson F, Dudley DJ, Spong CY, Peaceman AM, Leveno KJ, Malone F, Caritis SN, Mercer B, Harper M, Rouse DJ, Thorp JM, Ramin S, Carpenter MW, Gabbe SG; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network . Long-term outcomes after repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids. N Engl J Med 357: 1190–1198, 2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiland F, Verspohl EJ. Local formation of angiotensin peptides with paracrine activity by adipocytes. J Pept Sci 15: 767–776, 2009. doi: 10.1002/psc.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whorwood CB, Firth KM, Budge H, Symonds ME. Maternal undernutrition during early to midgestation programs tissue-specific alterations in the expression of the glucocorticoid receptor, 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms, and type 1 angiotensin ii receptor in neonatal sheep. Endocrinology 142: 2854–2864, 2001. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wirtschafter DD, Danielsen BH, Main EK, Korst LM, Gregory KD, Wertz A, Stevenson DK, Gould JB; California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative . Promoting antenatal steroid use for fetal maturation: results from the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative. J Pediatr 148: 606–612, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yiannikouris F, Karounos M, Charnigo R, English VL, Rateri DL, Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Adipocyte-specific deficiency of angiotensinogen decreases plasma angiotensinogen concentration and systolic blood pressure in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R244–R251, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00323.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Massmann GA, Rose JC, Figueroa JP. Differential effects of clinical doses of antenatal betamethasone on nephron endowment and glomerular filtration rate in adult sheep. Reprod Sci 17: 186–195, 2010. doi: 10.1177/1933719109351098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]