Abstract

Calcium-binding protein spermatid-specific 1 (CABS1) is expressed in the human submandibular gland and has an anti-inflammatory motif similar to that in submandibular rat 1 in rats. Here, we investigate CABS1 in human saliva and its association with psychological and physiological distress and inflammation in humans. Volunteers participated across three studies: 1) weekly baseline measures; 2) a psychosocial speech and mental arithmetic stressor under evaluative threat; and 3) during academic exam stress. Salivary samples were analyzed for CABS1 and cortisol. Additional measures included questionnaires of perceived stress and negative affect; exhaled nitric oxide; respiration and cardiac activity; lung function; and salivary and nasal inflammatory markers. We identified a CABS1 immunoreactive band at 27 kDa in all participants and additional molecular mass forms in some participants. One week temporal stability of the 27-kDa band was satisfactory (test–retest reliability estimate = 0.62–0.86). Acute stress increased intensity of 18, 27, and 55 kDa bands; 27-kDa increases were associated with more negative affect and lower heart rate, sympathetic activity, respiration rate, and minute ventilation. In both acute and academic stress, changes in 27 kDa were positively associated with salivary cortisol. The 27-kDa band was also positively associated with VEGF and salivary leukotriene B4 levels. Participants with low molecular weight CABS1 bands showed reduced habitual stress and negative affect in response to acute stress. CABS1 is readily detected in human saliva and is associated with psychological and physiological indicators of stress. The role of CABS1 in inflammatory processes, stress, and stress resilience requires careful study.

Keywords: calcium-binding protein spermatid-specific 1, saliva, acute and chronic stress, negative affect, cortisol, submandibular rat 1, anti-inflammatory activity

saliva has been used successfully to analyze changes in hormonal, immune, and enzymatic activity related to stress in humans (5a, 46, 47). Most frequently, salivary free cortisol has been analyzed, and increases have been demonstrated in paradigms of laboratory speech and mental-challenge tasks (24, 30). Other studies have identified a range of markers involved in the innate mucosal immune response, such as IgA, mucins, lactoferrin, and cystatin S, which respond to acute laboratory (7, 54, 75) or real-life (6, 28, 40, 48) stress. Markers of adaptive immune activity, such as ILs or chemokines, have also been found secreted in saliva and altered by stressors in the laboratory (27, 53) or real life (2, 76). Exploration of stress-sensitive protein markers in saliva continues to evolve (10, 34, 46, 70, 75), and discovery of new markers and their function in organisms’ adaptation to challenge and adverse life conditions holds promise for improved understanding of the stress response and the development of novel interventions.

One such marker may be calcium-binding protein, spermatid-specific 1 (CABS1), previously also known as casein-like phosphoprotein, chromosome 4, open-reading frame 35, and testis development protein NYD-SP26, identified in spermatids in selected phases of spermatogenesis and originally thought to be testis specific (11, 29). However, recently, we detected CABS1 expression in human submandibular and parotid glands and lungs and described multiple molecular weight forms of CABS1, the profile that appears to be tissue specific (71). Moreover, we discovered that human CABS1 contains an amino acid sequence (TDIFELL) with anti-inflammatory activities and with close homology to an anti-inflammatory sequence (TDIFEGG) identified in a related salivary gland protein, submandibular rat 1 (SMR1) (38).

Interestingly, SMR1 is a prohormone with peptide fragments that have a diversity of biological activities, ranging from inhibition of inflammatory responses (18, 33, 37, 41) to effects on erectile function (41, 72, 79), analgesic activity (60), and modulation of mineral balance in tissues (61). SMR1 is under neuroendocrine regulation (39, 45, 59), and it has been postulated that its fragments and their functions are differentially regulated by autonomic and endocrine pathways.

Given that CABS1 may be an ortholog of SMR1, with similar tissue distribution and multiple molecular weight forms, we postulated that CABS1 might be influenced by neuroendocrine pathways as is SMR1. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether CABS1 might be found in human saliva and whether its levels might be influenced by acute or prolonged stress, perhaps in a manner similar to the effects of stress on cortisol levels in saliva. Specifically, we examined susceptibility of CABS1 to an acute psychosocial stressor in the laboratory with a free speech and mental arithmetic challenge under evaluative threat. This design also allowed us to study the association of CABS1 with typically well-documented, short-term cortisol elevations following stress (24), as well as cardiorespiratory responses to the stress protocol. CABS1 was also measured in college students during a final exam stress period and compared with a low-stress period during their academic term. This protocol allowed for the examination of stress levels sustained over multiple days and also the association of CABS1 with slower developing inflammatory processes. In addition, we sought to examine the temporal stability of CABS1 levels across multiple weeks. All three studies also provided us with the opportunity to study the association of CABS1 with basic demographics, asthmatic vs. nonasthmatic status, and measures of negative affect, including perceived stress, anxiety, and depression.

METHODS

Overview of Studies

Saliva samples were collected from participants in three studies. Study 1 included a multiple baseline study with five weekly assessments to study the temporal stability of CABS1 and baseline associations with questionnaire measures of negative affect. In study 2, participants were administered a psychosocial laboratory stress-induction tool with a speech and mental arithmetic stressor under evaluative threat, which allowed us to study the response of CABS1 to an acute psychosocial stressor under controlled conditions. Study 3 was an observational protocol of academic final examination stress, allowing us to examine the response of CABS1 to conditions of more sustained real-life stress. Participants in the two stress protocols participated in larger data collections, focused on stress and airway inflammation in health and asthma (57, 74a, 77), and the protocols included salivary cortisol measures and exhaled nitric oxide as a marker of airway inflammation. VEGF and leukotriene B4 (LTB4)—markers of inflammatory processes—were collected from the upper airways in one of these protocols.

Participants

For the laboratory stress study, participants were recruited mostly from the undergraduate psychology research volunteer pool at a university in the Southwestern US and additionally, from the community. Students received extra course credit points for participation. Those not interested in credit and community participants were reimbursed with $35 (in studies 2 and 3) for their time. Participants had to be free of known respiratory diseases, except for asthma in studies 2 and 3. Exclusion criteria also included self-reported current smoking and any severe heart conditions, such as angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, transient ischemic attacks, or cerebrovascular accidents. Those with asthma required a physician diagnosis of their condition and no administration of oral or injected corticosteroids in the previous 6 wk (or 3 mo in study 2). Asthma control was rated according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (20a). Studies were approved by the local Institutional Review Board in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), and all participants provided written, informed consent.

Collection of Saliva

Saliva samples were collected with cotton swabs (Salivettes; Sarstedt, Newton, NC), which participants placed in their mouth for 2 min. Once completed, participants placed them into individual plastic capsules. Samples were frozen at –80°C until they were analyzed. For analyses, cotton swabs were centrifuged, and collected saliva volumes were recorded to account for changes in salivary flow, which may affect protein concentrations across assessments.

Salivary samples were shipped to the University of Alberta (Edmonton, AB, Canada) on dry ice and then stored at −20°C until analyses. As described previously for Western blot analyses (71), saliva samples were boiled in 1% SDS with 20 mM 1,4-DTT for 5 min, and then proteins were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gels (25 μg salivary protein solution was loaded for each sample) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Prestained protein standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were run on each gel with rabbit anti-CABS1 (immunogen was amino acids 184–197; DEADMSNYNSSIKS) primary antibody that was affinity purified with the immunogen (previously identified as H2 antibody AB_2571742) (71) at a final concentration of 3 µg/ml. Preimmune serum from rabbit H2 was used as an isotype control, and as a blocking control, the immunizing peptide was incubated in 10× amounts (30 µg/ml) with H2 (3 µg/ml) for 18 h before applying to the membrane. Omission of the primary antibody was also used as a negative control. The secondary antibody was IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit (1:10,000; AB_621843; Mandel, Guelph, ON, Canada). Mouse anti-human β-actin (AB_1119529) was used to assess protein loading (1:5,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) with the secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IRDye 680 (AB_10956588; Mandel). Blots were visualized with an Odyssey imager (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) by scanning simultaneously at 700 and 800 nm. Odyssey software was used for molecular weight determination and quantitation of band intensity on Western blots.

To standardize quantitation of bands, an internal control was established using a human submandibular gland extract that we previously described (71). This standard sample was run on each Western blot, and all immunoreactive bands detected in saliva were normalized to the 27-kDa band from this human submandibular gland extract and reported as relative fluorescent units. All saliva samples were run in duplicate on different days, and their normalized values were averaged.

Detection of Salivary Cortisol

Salivary cortisol concentrations were determined using a commercially available kit, Coat-A-Count cortisol kit (cat. no. TKCO2; Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA), which had a detection limit of 0.03 pg/ml with serial dilution of the lowest calibrator standard.

Additional Physiological Measures

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) was measured with a hand-held electrochemical analyzer (Niox Mino; Aerocrine, Solna, Sweden) in accordance with current guidelines (1, 68). Major sources of measurable airway nitric oxide are epithelial cells in healthy individuals and a variety of immune cells, including macrophages, mast cells, and eosinophils, in individuals with allergic asthma (19, 20, 33, 52). One exhalation was performed against a stable resistance of 50 ml for a duration of 10 s. Participants were instructed not to eat and only to drink water, 2 h before assessments, to avoid the influences by nitrate-rich foods. Exercise or heavier physical activity was also discouraged for at least 1 h before the session. Spirometric lung function was measured in study 3 with a hand-held electronic spirometer (AM2; Jaeger/Toennies, Würzburg, Germany) as the best of three blows.

As parameters reflecting upper airway inflammatory activity, VEGF was measured in nasal fluid and LTB4 in nasal fluid and saliva. Collection of saliva followed the same protocol as outline above. Nasal fluid was sampled by 3 ml saline solution (0.9% sodium chloride; Addipak Unit Dose Solutions, model HUD20039; Teleflex Medical, Morrisville, NC), instilled into each nostril with an Intranasal Mucosal Atomization Device (LMA MAD Nasal syringe; Teleflex Medical). The liquid was collected in a kidney dish and transferred into small storage tubes (58, 74a).

The samples were stored immediately at –80°C. For analysis, samples were concentrated twofold using an Eppendorf Vacufuge and a Fisher Scientific MaximaDry vacuum pump. With the use of enzyme immunoassay kits (Enzo Life Science, Plymouth Meeting, PA), the amounts of LTB4 and VEGF were determined, as described in Trueba et al. (74a). The detection limits of the kits were 5.6 pg/ml for LTB4 and 14.0 pg/ml for VEGF. Controls were performed that showed that the increased salt concentration, resulting from the vacuum concentration of the samples, did not affect the sensitivity of the kits.

In study 2, the electrocardiogram and respiration were measured by respiratory inductance plethysmography (LifeShirt; VivoMetrics, Ventura, CA) with two inductance bands for the thorax and abdomen, with Ag/AgCl electrodes placed on the sternum, left costal arch of the 10th rib, and left clavicle. Signals were amplified and analog-to-digital converted with a sampling rate of 200 Hz. Bands were calibrated using a fixed volume bag (800 ml), followed by offline qualitative diagnostic calibration (62) and fixed volume calibration. A dedicated biosignal analysis program (Vivologic; VivoMetrics) was then used to eliminate artifacts (e.g., ectopic beats, movement artifacts) and extract relevant parameters. For respiratory parameters, tidal volume (VT) and total respiratory cycle time (TTOT) were extracted and also used to calculate minute ventilation (V̇E). Heart rate (HR) was calculated from the distance between adjacent R-waves. The cardiac T-wave amplitude (TWA; in millivolts) was extracted using the ECG boundary location function (32), embedded in the AcqKnowledge biosignal analysis software package (version 4.1; Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA). The TWA has been used as a surrogate measure of cardiac sympathetic activity because of its sensitivity to isoproterenol and β-adrenergic blockade (15, 31, 43, 51). In adults, stressful laboratory challenges typically attenuate the TWA (25, 31, 64). Although measures from impedance cardiography are more common for noninvasive estimation of cardiac sympathetic activity (50, 67), the implementation of this technique was not possible in this study because of the potential for interference with the respiratory inductance plethysmography measurements. As a noninvasive estimate of cardiac vagal activity, respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) was extracted from fluctuations of the interbeat interval in the time domain by the peak-valley method (21) using the customized RSA Toolbox software (65). RSA was log transformed to improve distributional characteristics. Because RSA is strongly influenced by the respiratory pattern (5, 9, 21, 22, 26), with both longer and deeper breaths increasing RSA—potentially independent of cardiac vagal activity changes—an additional within-individual correction of RSA was used (56). Raw RSA was normalized by VT (RSA/VT); then coefficients from a within-individual regression equation, based on the pace-breathing measurements, were used to determine the predicted RSA/VT for any given TTOT during the experiment; and the deviation of observed from predicted RSA/VT was then calculated. This strategy has been shown to improve the estimation of cardiac vagal activity (21, 55, 63). The grand mean of unadjusted RSA/VT was added to obtain the respiration-corrected RSA, and the resulting values were log transformed. Results are also reported for respiration-uncorrected logRSA, to allow comparison with existing literature that does not control for respiration.

Questionnaire Measures

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (16, 85) was used to assess depressive mood and anxious mood in the past week. Current-state negative affect was assessed with the negative affect subscale of the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS-NA) (82). An additional ad hoc rating scale (0 = “not at all”; 10 = “extremely”) was used to measure how much stress participants felt in the moment in study 1. Perceived stress was assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (13, 14), which measures feelings of being overwhelmed and unable to cope with challenges in the past 4 wk. The 10-item version was used at the beginning of all studies, except for approximately one-half of the participants of study 1 (n = 30), who were administered the abbreviated four-item version to reduce the overall burden of the assessments in the second wave. Symptoms of acute upper respiratory infections (common cold) were measured with the Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WURSS)-21 (3). Symptom severity was captured with 10 items on an 8-point scale, ranging from 0 (“do not have this symptom at all”) to 7 (“severe”). The scale has good change sensitivity and a positive association with biological infection markers (3, 4).

Procedures

Study 1.

For multiple baseline assessments, participants were invited for five weekly assessments over a period of 4 wk. Day of the week was kept constant for individual participants, as was time of day (between 8 AM and 6 PM) to control for diurnal effects. In each session, participants provided saliva samples and performed measurements of FeNO. Afterwards, participants completed a questionnaire battery at a computer terminal. Upon completion of the fifth visit, participants were debriefed about the purpose of the study.

Study 2.

Participants attending sessions in this study were administered the Trier Social Stress Test (30). Sessions were scheduled in the early afternoon, beginning between 12 and 3 PM. Initially, participants completed a questionnaire battery, including trait measures of stress, anxiety, and depression. After the baseline assessments, the participants were told that they will be asked to give a presentation, which should make a particularly good case for them as candidates for the chief executive officer position of a major US retailer. Two “experts on presentation skills” (one male and one female confederate of the experimenter), who would evaluate the performance regarding intelligence, creativity, and body language, were then introduced briefly to the participants. Each participant was then given 5 min alone to prepare the speech. Afterwards, the experts returned, and the participant was expected to give a 5-min speech standing in a conference room with a video camera turned on. Then, the participants were unexpectedly asked to perform a mental arithmetic task that consisted of subtracting the number 13 from the number 6,233 and to keep subtracting the remainder aloud as accurately and as quickly as possible. The duration of the mental arithmetic task was 5 min. Throughout, the confederates were required to maintain neutral facial expression and offer no encouragement. Only simple instructions were provided to continue with the speech or to start again from the beginning when the arithmetic task contained a mistake. Saliva samples were scheduled at 15 and 0 min prestress and at 0, 15, 30, and 45 min poststress. Participants also completed a questionnaire on momentary negative affect at these time points. Quiet sitting measures of cardiac and respiratory activity were initiated 3 min before saliva sampling and FENO measurement at 18 and 3 min prestress and at 12, 27, and 42 min poststress. Additional measures during the 10 min of stress task performance were extracted in 2.5-min increments, of which the last 2.5-min increment of the mental arithmetic task was used as a measure preceding the first 0-min poststress saliva sample. For poststress assessments, participants returned to sitting posture and were then fully debriefed, and the experimenter explored any signs of residual distress. Before the session, participants with asthma were asked to discontinue short-acting bronchodilators for 6 h, long-acting beta-adenergic agonists for 12 h, and leukotriene modifiers for 3 days.

Study 3.

Participants provided data at three assessment points: one at a low-stress period during the middle of the term when participants had no exams or major projects and two during the 10 days of final academic exams at the end of the term. The low-stress assessment was scheduled 2–6 wk before the first final exam assessment. During the exam period, an early and a late final exam assessment were spaced 5 to 7 days apart. Assessments thus captured sustained academic pressures associated with a final exam period rather than acute stress of an examination (6). To control for diurnal effects, each participant was scheduled at the same time of day for all assessments. At each assessment, participants completed a questionnaire package, followed by saliva collection and FENO assessments. After the third session, participants were thanked and debriefed about the purpose of the study. For participants with asthma, the same instructions for discontinuation of medication were used as in study 2.

Data Reduction and Analyses

In study 1, data were obtained from a total of 64 participants (51 women). Three of the participants had asthma and were excluded from the group statistics to reduce potential variability. From the remaining participants, 60 provided samples in the first and second assessment, 48 in the third assessment, 50 in the fourth assessment, and 47 in the fifth assessment. Pearson correlations were calculated to study the stability of the levels of the 27-kDa band across assessments. Studies 2 and 3 involved 16 (11 women) and 19 participants (18 women), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the 3 studies of CABS1 in saliva

| Study 1, n = 64 | Study 2, n = 16 | Study 3, n = 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, women, n (%) | 51 (79.7) | 6 (37.5) | 18 (94.7) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 20.2 (4.3) | 33.6 (15.0) | 19.8 (1.0) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 39 (61.9) | 14 (87.5) | 16 (84.2) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 10 (15.9) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (10.5) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 3 (4.7) | 10 (62.5) | 6 (31.6) |

| Asthma, n (%) women | 3 (100.0) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| Asthma well controlled, n (%)* | 3 (100.0) | 8 (80.0) | 5 (83.3) |

| Age of asthma onset, yr, mean (SD) | Not available | 6.3 (6.1) | 7.8 (4.8) |

| Maintenance medication, n (%) | 0 (0.00) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (50.0) |

Rated according to Global Initiative for Asthma (2013) (20a).

Mixed effects models (MEMs) were used to analyze the data, since these models are intent-to-treat analyses that include all subjects, regardless of missing data. Two sets of analyses were conducted for each study. First, we examined the longitudinal associations between the 27-kDa band and possible related predictors, including demographics, mood, lung function, and physiological measures. Because recent research indicates that to assess accurately the longitudinal relations between variables, one must disaggregate the between-subjects effects from the within-subjects effects (81), we first calculated the average level of each predictor for each individual across the assessments. This average level provided the score for the between-subjects differences in the predictor. Then, for each predictor, we calculated the deviations from the average level for each individual at each assessment. These deviation scores provided the within-subjects measures of changes in the predictor over time. Both the deviation scores and the average scores were included as predictors of the 27-kDa band in the MEMs. We also included asthma status (yes/no), age, body mass index (BMI), and time as control variables in all analyses.

The second set of analyses examined the change in our variables over time. These analyses were performed as repeated-measures ANOVAs, using MEMs to calculate the ANOVAs (which therefore retain all participants regardless of dropout or missing data). We modeled the covariance matrix of the errors of the repeated measures as “unstructured” in all MEMs.

RESULTS

Abundance of Bands Immunoreactive to CABS1

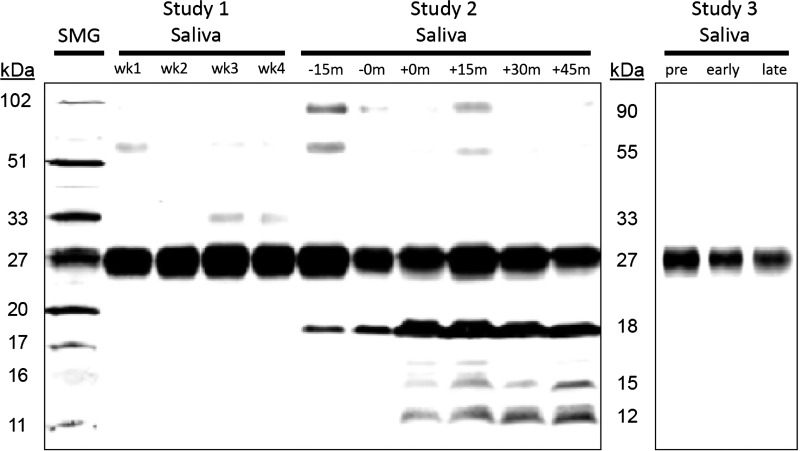

Western blot analyses of the saliva identified a 27-kDa band of CABS1 in each of the 99 participants of the 3 studies (for basic description of participants, see Table 1). In 13 participants across the three studies, low-abundance CABS1 immunoreactive bands below 27 kDa were also detected at 20, 18, 15, and/or 12 kDa (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The extra bands were seen in relatively greater proportions in men (20.8%) than women (10.6%). They also tended to co-occur; thus three women and one man showed both 18 and 12 kDa bands, one man showed bands at 18, 15, and 12 kDa, and two women showed all four bands at 20, 18, 15, and 12 kDa. The 12-kDa band was found alone in two women and the 18-kDa band alone in three men and one woman. Participants with extra bands below 27 kDa self-identified as white, except for one with a 12-kDa band who was African-American and had asthma, and one with an-18 kDa band who was Hispanic and had no asthma. One of the women with all four additional bands identified as white and had asthma.

Table 2.

Abundance of immunoreactive bands of CABS1 in 3 studies for total sample and for subsamples of women

| 90 kDa | 55 kDa | 33 kDa | 27 kDa | 12 kDa | 15 kDa | 18 kDa | 20 kDa | Total 12–20 kDa | Total 33–90 kDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1, n = 64, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 64 (100.0) | 5 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Women, n = 51, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (100.0) | 5 (9.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Study 2, n = 16, n (%) | 5 (31.3) | 7 (43.8) | 1 (6.3) | 16 (100.0) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.3) | 5 (31.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (31.3) | 7 (43.8) |

| Women, n = 6, n (%) | 3 (18.1) | 3 (36.4) | 0 (9.1) | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (36.4) |

| Study 3, n = 19, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (100.0) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (15.8) |

| Women, n = 18, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (100.0) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (16.7) |

| Total, n = 99, n (%) | 5 (0.5) | 10 (10.1) | 1 (0.0) | 99 (100.0) | 9 (9.1) | 3 (3.0) | 11 (11.1) | 2 (2.0) | 13 (13.1) | 10 (10.1) |

| Women, n = 75, n (%) | 3 (4.0) | 6 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | 75 (100.0) | 7 (9.3) | 2 (2.6) | 6 (8.0) | 2 (2.6) | 8 (10.6) | 6 (8.0) |

Fig. 1.

CABS1 is detected in saliva at varying molecular weights among different individuals and stress conditions. A representative Western blot showing CABS1 detected in saliva from 3 different individuals across 3 studies. Lane 1 contains human submandibular gland (SMG) as a normalization control. Lanes 2–5 contain saliva samples collected weekly over 4 wk from 1 participant in study 1 (multiple baseline assessment). Lanes 6–11 contain saliva samples collected at 6 time points (−15 and −0 m are prestress; +0, +15, +30, and +45 m are poststress) from 1 participant during study 2 (acute laboratory stress). Lanes 12–14 contain saliva samples collected at 3 time points (pre is before exams begin; early and late are during exams) from 1 participant in study 3 (final exam stress). All lanes were loaded with 25 μg protein, and all immunoreactive band intensity values were normalized to the 27-kDa band in SMG.

An additional 10 participants also showed bands with a higher molecular mass between 33 and 90 kDa (Fig. 1); 6 of these were asthmatic. Proportionally, extra bands above 27 kDa were seen more in men (16.6%) than women (8%). A band at 55 kDa was most frequently seen, and it co-occurred with the 90-kDa band in five cases (2 of these were men). One man showed all three bands at 33, 55, and 90 kDa. All participants with extra bands in this range self-identified as white, except for one African-American woman with bands at 55 and 90 kDa.

Multiple Baseline Assessments: Study 1

Temporal consistency of CABS1 27-kDa band intensity levels in saliva.

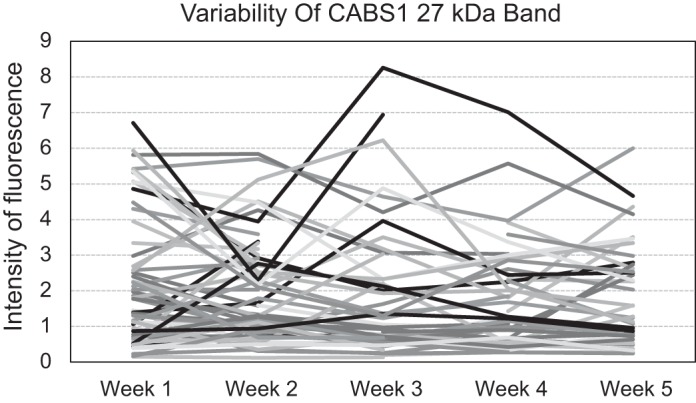

The consistency of the 27-kDa band intensity (relative fluorescent units normalized to the standard) in 25 μg salivary protein between individuals was very good to fair in the range of test–retest reliability estimate = 0.51–0.86 (Table 3; lower correlation matrix) across all weeks. This was comparable with the consistency of FENO levels (Table 3; upper correlation matrix). Consistency of the levels did not decline for the 27-kDa band as a function of time, whereas such a decline was the case for FENO. Intensity of the 27-kDa band across weeks did not change significantly for the sample overall, although there was some fluctuation of individual intensity levels (Fig. 2). Saliva volume did not change significantly across time points (P = 0.537).

Table 3.

Comparison of the stability of CABS1 (27 kDa; lower half of matrix) in saliva and of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (upper half of matrix) in study 1 (5 weekly baseline assessments)

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 1 | 0.68 (57) | 0.66 (49) | 0.66 (50) | 0.54 (43) |

| Week 2 | 0.62 (55) | 1 | 0.84 (49) | 0.77 (49) | 0.70 (43) |

| Week 3 | 0.70 (43) | 0.62 (44) | 1 | 0.81 (42) | 0.77 (37) |

| Week 4 | 0.51 (44) | 0.63 (45) | 0.86 (37) | 1 | 0.78 (38) |

| Week 5 | 0.72 (43) | 0.67 (43) | 0.81 (35) | 0.66 (36) | 1 |

All P < 0.001. Pearson correlations (r) are shown; sample n in parentheses.

Fig. 2.

CABS1 band of 27 kDa for individual participants across 5 weekly baseline assessments.

Association of the CABS1 27-kDa band with demographics and negative affect.

No significant associations were found for the quantitative assessment of the 27-kDa band with age, gender, race, or ethnicity. The quantity of the 27-kDa band was positively associated with BMI (P < 0.05). Participants with overall higher ratings of current stress had higher amounts of the 27-kDa band (P < 0.001), as had those with a higher depressive mood in the past week (HADS depressive mood; P < 0.05), as well as those with a higher anxious mood in the past week (HADS anxious mood; P < 0.10), after controlling for age, gender, BMI, and assessment wave.

Association of the CABS1 27-kDa band with airway nitric oxide.

FENO changes from week to week were positively associated with 27 kDa band changes (P < 0.01), after controlling for age, gender, BMI, and assessment wave.

Acute Laboratory Stress: Study 2

Effects of acute stress on the CABS1 band at 27 kDa in saliva.

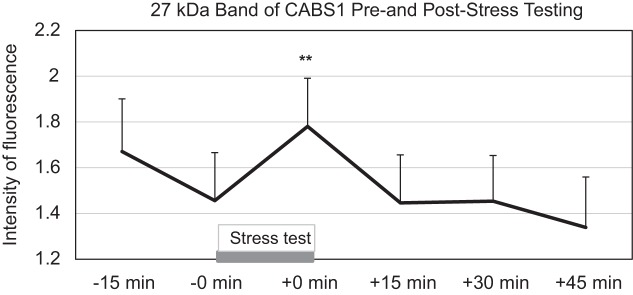

MEM analysis indicated that the 27-kDa band changed significantly over pre- and poststress assessments (P < 0.01), with visible and significant increases from 0 min prestress to 0 min poststress (P < 0.01) and a drop at 45 min poststress (P < 0.05; Fig. 3). Saliva volume varied significantly across time [F(5,13) = 3.66, P = 0.028], which was probably due to higher values for the initial 15-min prestress measurement relative to subsequent measurements, but none of the individual time point comparisons was significant (P > 0.112).

Fig. 3.

CABS1 band of 27 kDa during the laboratory stress assessment protocol with the Trier Social Stress Test. **P < 0.01 relative to measurement at 0 min before stress (−0 min).

Association of the CABS1 band at 27 kDa with demographics and negative affect.

No significant associations were observed between the levels of the 27-kDa band and age, gender, or race/ethnicity. Changes in PANAS-NA were positively associated with changes in the levels of the 27-kDa band (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Between- and within-subject associations of the CABS1 27-kDa band with other physiological parameters and the negative-affect rating and time effects of parameters across the Trier Social Stress Test (study 2)

| Timea | Betweenb | Withinb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 28.7‡ | −0.08‡ | −0.03‡ |

| TWA | −0.13‡ | 3.70 | 1.37* |

| logRSA | −10.5* | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| logRSAc | −8.23 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| TTOT | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.13† |

| VT | −0.03 | −0.19 | −0.15 |

| V̇E | 0.81 | −0.01 | −0.03* |

| FENO | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.15 |

| Salivary cortisol | 1.05 | −0.06 | 0.02* |

| PANAS-NA | 0.49† | −1.06 | 0.34† |

| PSS | −0.26 | ||

| 27 kDa band | 0.32† |

Results are from mixed effects models (MEMs) analyses of individual parameters as a single-time varying covariate of the 27-kDa band. Time effects show contrast of 0 min prestress vs. final 2.5 min of the math stressor for cardiac and respiratory indices, 0 min prestress vs. 0 min poststress for FeNO, and 0 min prestress vs. the mean of 0, 15, 30, and 45 min poststress for cortisol. For Time effects, positive coefficients indicate increases over 0 min prestress and negative coefficients indicate decreases. HR, heart rate; TWA, T-wave amplitude; logRSA, logarithm of respiratory sinus arrhythmia; logRSAc, logarithm of respiratory sinus arrhythmia corrected for tidal volume (VT) and residualized by total respiratory cycle time (TTOT); V̇E, minute ventilation; FENO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; PANAS-NA, Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule subscale negative affect; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Controlling for age and gender.

Controlling for age, gender, and time.

Association of the CABS1 band at 27 kDa with salivary cortisol, FENO, and cardiorespiratory activity.

MEM analyses, controlling for age, gender, BMI, and time, showed a higher overall 27-kDa band intensity for participants with lower HR (P < 0.001). Within subjects, greater increases in the 27-kDa band were related to weaker HR increases (P < 0.001), less reduction in TWA (P < 0.05), slower breathing (longer TTOT; P < 0.01), and greater cortisol increases (P < 0.05; Table 4).

Academic Exam Stress: Study 3

Effects of final exam stress on CABS1 in saliva.

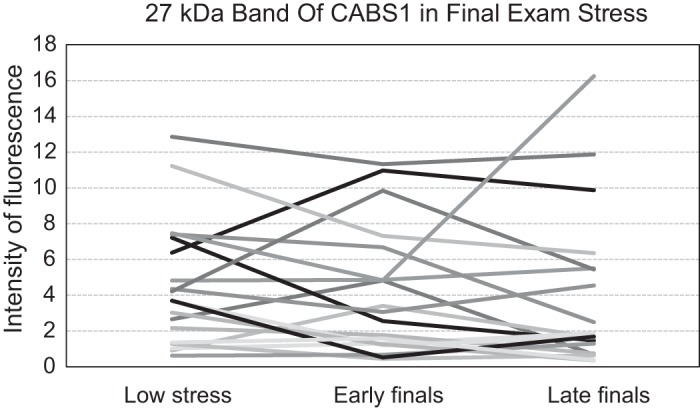

MEM analysis with the three time points did not show any significant change in the 27-kDa band over time. Including the between-subject group variable asthma (yes/no) did not change the findings. No group differences or interactions of time with the group variable were found. The 27-kDa band showed a marked variability in the direction of change from low to high stress periods (Fig. 4). Saliva volume remained stable across measurements (P = 0.775). To examine whether date of sample testing impacted the 27-kDa band, we performed a cross-classified MEM, with baseline date, early exam date, and late exam date as a cross-classified grouping variable for the 27-kDa band level. We found no effect of any cross-classified groupings (baseline data, early exam date, or late exam date) on the level of the 27-kDa band (P > 0.238).

Fig. 4.

CABS1 band of 27 kDa for individual participants during low stress and final exam stress periods.

Association of the CABS1 27-kDa band with demographics, negative affect, and asthma.

The 27-kDa band was not substantially associated with age, gender, or asthma status but showed a marginal positive association with BMI (P < 0.10). Variables of negative affect were not significantly associated with the band in this sample (Table 5).

Table 5.

Between- and within-subject associations of the CABS1 27-kDa band with other physiological parameters and the negative-affect rating and time effects of parameters across low stress (during term) and high stress (early and late in finals) periods

| Timea | Betweenb | Withinb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salivary cortisol | 0.01 | 12.1† | 3.74* |

| FENO | −0.06§ | 0.09 | 1.77 |

| FEV1 | −6.08‡ | −0.03 | −0.00 |

| Nasal VEGF | 33.0* | 0.04* | 0.00 |

| Nasal LTB4 | −0.63* | 0.75 | 0.27 |

| Salivary LTB4 | −18.25 | 0.008* | 0.00 |

| PANAS-NA | 1.61‡ | −0.20 | −0.04 |

| PSS | −0.15 | ||

| WURSS-21 | 0.15 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| 27 kDa band | −0.32 |

Results are from MEM analyses of individual parameters as a single-time varying covariate of the quantity of the 27-kDa band. Time effects are linear trends from baseline to early-to-late final period, except for FENO, which is contrasted with baseline vs. early and late final period. Negative coefficients indicate decreases, and positive coefficients indicate increases of the respective parameter during final periods relative to baseline. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; LTB4, leukotriene B4; WURSS-21, Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Scale 21 (see Table 4 legend for other abbreviations).

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.10.

Controlling for group, age, and BMI.

Controlling for group, age, BMI, and time.

Association of the CABS1 27-kDa band with salivary cortisol and FEV1.

The levels of the 27-kDa band were positively and significantly associated with levels of cortisol, both between (P < 0.01) and within (P < 0.05) subjects, after controlling for group, age, BMI, and time (Table 5). Thus participants with higher overall levels of cortisol had higher 27 kDa band values, and changes in cortisol from low to high stress exam periods were also positively associated with changes in the 27-kDa band. No association was found between CABS1 in saliva and forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1).

Association of the CABS1 27-kDa band with inflammatory markers.

FENO increases within subjects were associated positively and in concordance (P < 0.10) with the 27-kDa band, but the addition of time as a covariate eliminated the effect. Between subjects, higher levels of salivary LTB4 and nasal VEGF across assessments were associated with higher levels of the 27-kDa band (P < 0.05; Table 5).

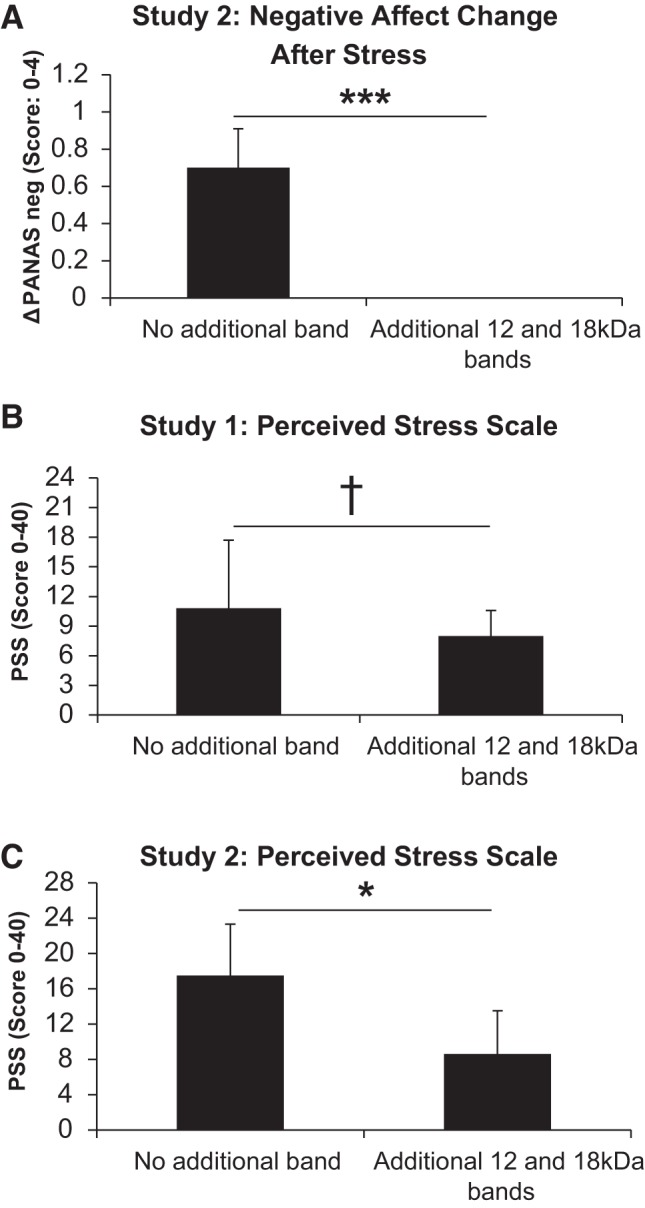

Exploratory Analyses of Additional Immunoreactive Bands in the Three Studies

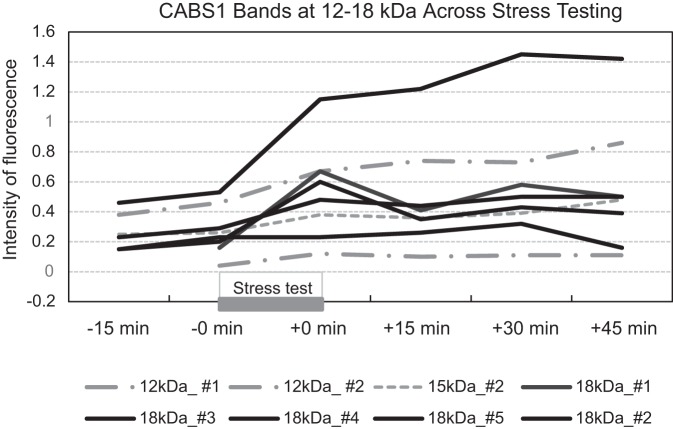

Because few participants showed additional bands immunoreactive to CABS1 beyond the 27-kDa band, analysis of these bands was highly exploratory. The 18-kDa band in five participants of study 2 showed a substantial increase following the stress test (Fig. 5), with a significant time effect in the MEM analysis [F(5,19) = 7.31, P < 0.001] and significant elevations in levels from 0 min prestress to 0 min poststress (P < 0.001) and 30 min poststress (P = 0.029). These participants showed no change in PANAS-NA from 0 min prestress to 0 min poststress compared with the remaining 11 participants who showed increases in PANAS-NA but lacked the additional bands (Mann-Whitney U = 0.00, P < 0.001; in Fig. 6A, note that U was 0 because there was no overlap in ranks between both groups). Significant increases following the laboratory stressor were also observed in seven participants who showed a 55-kDa band [F(5,28) = 3.37, P = 0.017], with significant elevations from 0 min prestress to 0 min poststress (P < 0.001). However, participants with this band did not differ in their PANAS-NA response from those without the band. Elevations after stress were also observed in the 90-kDa band (n = 5 participants), but no significant time effect emerged (P = 0.333).

Fig. 5.

Effects of the Trier Social Stress Test on levels of CABS1 bands of 18, 15, and 12 kDa for 5 individual participants.

Fig. 6.

A: changes in negative affect [PANAS negative-affect subscale (ΔPANAS neg)] in response to the Trier Social Stress Test in those with (n = 5) and without (n = 11) additional CABS1 bands at 18, 15, and/or 12 kDa. ***P < 0.001. B: perceived Stress Scale (PSS) scores in those with (n = 6) and without (n = 24) additional CABS1 bands at 18 and/or 12 kDa in study 1. †P < 0.10. C: PSS scores in those with (n = 5) and without (n = 11) additional CABS1 bands at 18, 15, and/or 12 kDa in study 2. *P < 0.05.

In study 3, although only two participants showed additional CABS1 bands, the abundance of the 20-, 18-, 15-, and 12-kDa molecular forms was elevated at the late exam stress time (5- to 60-fold) compared with the baseline or early exam stress period.

Participants with additional bands at molecular mass 12–18 kDa showed significantly lower values in the PSS in study 2 [U = 7.0, P = 0.018 (n1 = 5, median = 5; n2 = 11, median = 16)] and a trend toward lower values in the second wave of study 1 [U = 36.5, P = 0.065 (n1 = 6, median = 7.5; n2 = 24, median = 11)] (Fig. 6, B and C). No participants of those receiving the 10-item version of the PSS in study 1 showed additional bands. Participants with additional bands at molecular mass 33–90 kDa did not show significantly lower values in PSS than those without these bands.

DISCUSSION

Our studies provide the first description of CABS1 and its multiple forms in human saliva and the association with psychological stress and inflammation. The predominant molecular form of CABS1 was detected at 27 kDa, and additional immunoreactive bands were also identified between 12 and 20 kDa and between 33 and 90 kDa in a small (13/99 and 10/99, respectively) number of participants.

We originally identified CABS1 in human salivary gland extracts (71) during our search for a human protein with a sequence similarity to the anti-inflammatory peptide sequence near the carboxy terminus of the rat prohormone, SMR1 (36, 44). The Smr1 gene we studied in rats is not present in humans, and although sequence similarity for other peptides derived from Smr1 with analgesic or erectile function activities had been identified in human PROL1 and SMR3A and SMR3B genes (73, 74, 79), the human gene with a sequence similar to the anti-inflammatory sequence from Smr1 was unknown. Interestingly, just as SMR1 has many molecular forms that vary in size and isoelectric point (45), with the use of Western blot analyses and five different anti-CABS1 antibodies, we identified several molecular forms of CABS1 in salivary gland extracts, lungs, and testes, with evidence for organ-specific differences in the forms. With the use of mass spectrometry, we confirmed the presence of CABS1 sequences in bands at 75, 51, 33, 27, 20, and 16 kDa from a CABS1 overexpression lysate but could not confirm or refute that an 11-kDa form was CABS1 (71). The predicted molecular size of human CABS1 is 43 kDa, a size inconsistent with any of the bands that we identified. Given our mass spectrometry data, we suggested that both the 75- and 51-kDa forms represent full-length CABS1 (good sequence coverage 69–73%) but could provide no explanation for the two molecular mass forms. Interestingly, others have similar observations with CABS1 from rat testes at 79 kDa (11), from mouse testes at 66 kDa (29), and from porcine testes at 70 and 75 kDa (66). CABS1 immunoreactive bands below 51 kDa presumably represent fragments of full-length CABS1 (proteolysis).

There are several potential explanations for detecting proteins at various estimated molecular weights relative to that predicted by their amino acid sequence, including the following: glycosylation, aggregation, proteolysis, and anomalous SDS binding due to amino acid content. Calvel et al. (11) provided evidence that CABS1 is an intrinsically disordered protein with a low isoelectric point (3.4), lacking a fixed or ordered structure and with unusual behavior in electrophoretic separation. Moreover, these authors showed that CABS1 is hypersensitive to trypsin digestion, suggesting structural flexibility and susceptibility to digestion with various proteases. This is consistent with our observations of multiple immunoreactive bands in salivary gland extracts, testes, and lung (71) and in saliva and tissue-specific distinctions in the band profiles, presumably determined, at least in part, by the protease cocktails in each tissue or fluid.

As we experienced with salivary gland extracts and despite several attempts to immunoprecipitate and sequence CABS1 immunoreactive bands from saliva, it is a limitation of our work that we have been unable to confirm the identity of these immunoreactive bands with mass spectroscopy. Our current hypothesis is that CABS1 is in relatively low abundance (we can detect by Western blot but are unable to see corresponding bands using silver staining or Coomassie brilliant blue), in part, because it is an intrinsically disordered protein that is highly susceptible to proteolytic cleavage, further lessening the abundance of any particular molecular form.

The 27-kDa form of CABS1 was present in the saliva from all participants and aligns well with 27 kDa in extracts of human salivary glands, lung, and testes (71). Although in some salivary gland extracts, the 27 kDa appeared to be a doublet (71), we could not clearly establish a doublet in saliva, perhaps because the band in saliva was relatively disperse, suggesting multiple forms. Whether the bands detected in saliva at 20, 18, 15, and 12 kDa are the same as CABS1 bands detected at 20 kDa and below in salivary gland extracts (20, 17, 16, and 11 kDa) remains to be determined. Nevertheless, given our work with several anti-CABS1 antibodies, mass spectroscopy sequencing of CABS1 molecular mass forms from overexpression lysates, and with several tissues, it is likely that all of these molecular forms in saliva have CABS1 sequences, i.e., are fragments of CABS1.

Interestingly, the molecular mass forms of CABS1 at 20 kDa and below were seen only in 13% of participants and relatively more in men (20.8 vs. 10.6%). Similarly, CABS1 forms at 33 kDa and above were seen more often in men (16.6%) versus women (8.0%). Sex differences in the prevalence of CABS1 forms would be consistent with the evidence of sexual dimorphism in SMR1 expression in rats (61). Larger samples with more equal ratios of men and women would be needed to consolidate these findings. It is tempting to speculate that the different molecular forms of CABS1 will have overlapping but potentially also distinct functions, including anti-inflammatory activities associated with the TDIFELL motif and with putative differences in their three-dimensional structures and potential receptor systems, as previously explored in studies of SMR1 and its molecular forms (37, 42, 60).

In part, because rat SMR1 is a marker of stress (61), we analyzed the levels of the CABS1 bands in saliva in response to standardized psychological stress induction, and their association with real-life stress, as well as common questionnaire measures of distress, and generated some intriguing findings. In general, findings suggest a sensitivity of CABS1 to acute stress and an association with self-reporting of perceived stress and depressive mood. Intensity of the 27-kDa band significantly increased following the laboratory psychosocial stress paradigm. On the other hand, no systematic changes were observed across periods of longer-lasting stress in our observational paradigm of academic finals stress. However, the variability of the 27-kDa band in the latter paradigm was considerable, with some individuals showing pronounced increases, others decrease, and others little change. It is possible that in longer real-life observational periods, additional moderator variables become more relevant that were not captured by our assessment protocols, such as individual coping resources or factors of changing environmental demand. Interestingly, greater increases in 27 kDa band intensity were associated with greater increases in cortisol in both the laboratory acute stress and chronic academic final examination protocols, suggesting an association with hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal axis functioning across different types of psychological stress (note that this association was found despite significant average changes of CABS1 and cortisol in the academic finals stress study). The observed between-subject association of salivary cortisol levels across assessments of academic finals stress further supports a link with hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal axis function. Whether these correlational findings represent any correspondence in the underlying physiological process remains to be explored. Recent research has shown that cortisol is not equally responsive to all types of stress; rather, it is particularly elevated in psychosocial stress and situations that constitute a threat to social self-esteem of the individuals and elicit social emotions, such as shame (23, 69). Thus our picture of hormonal adaptations to stress is far from complete. We do not view the purpose of our research in the identification of one, or the best, stress marker, but in the identification of the variety of possible organ and tissue responses to the variety of stress situations and styles of coping with stress. The present findings suggest that CABS1 protein secretion by the salivary glands is one of the hormonal pathways responding to stress, but whether it is activated in a more global fashion or more specific to particular stress challenges still has to be elucidated. Our initial finding of a diverging response to acute vs. chronic stress challenges is more suggestive of specificity.

Interestingly, the pattern of associations with autonomic and respiratory function across the acute stress protocol suggested an involvement in system deactivation rather than activation. Increases in 27-kDa band intensity were linked to slower breathing with reduced V̇E, reduced HR, and larger TWAs, the latter being suggestive of a reduced cardiac sympathetic activation. At the same time, no association was observed with RSA as an index of cardiac parasympathetic function. It therefore appears that CABS1 is related to an attenuated cardiorespiratory response to acute stress through dampening of sympathetic excitation. Because rat SMR1 secretion is regulated by both branches of the autonomic nervous system (45), with larger quantities of protein secreted in sympathetic stimulation, it is possible that the observed associations with human CABS1 may more closely reflect the effective outcome of CABS1 secretion on the autonomic and respiratory systems than the coordination of its initial secretion in response to stress. One function of CABS1 may be the dampening of acute stress responses, consistent with the interpretation that regulation of SMR1, the rat analog of CABS, may serve as a pathway in the organism’s protective responses, including anti-inflammatory activities following a variety of insults (45). Protocols with more frequent collection of saliva samples throughout stress periods or direct manipulation of the CABS1 pathway will be needed to determine the exact temporal trajectories of CABS1 secretion relative to changes in autonomic excitation.

Another interesting finding with the 27-kDa band of CABS1 was its systematic association with self-reported distress. Positive associations were found with changes in momentary affect across the acute stress protocol, with momentary stress-level ratings across multiple baseline assessments, and with questionnaires of perceived stress and depression in the past week(s). These findings are compatible with CABS1 upregulation during acute stress but complicate the interpretation of CABS1 associations with autonomic and respiratory parameters in acute stress. Thus whereas it appears that distress experience increases the CABS1 27-kDa band with some consistency, physiological concomitants are only partly compatible with such stress-induced increases. At this point, it is unclear whether this could be a reflection of other recent findings of reduced cardiac stress reactivity in depressed individuals (12, 35). Larger studies involving clinical groups and more extensive stress protocols will be needed to shed more light on these findings. Perhaps distinct functions of the multiple molecular forms of CABS1 will also help explain some of the complexities (see below).

The observational protocol of academic finals stress also enabled us to study CABS1 relative to slower developing inflammatory processes. Consistent with a role of SMR1 in inflammation, demonstrated in previous studies in animal models (39, 45), we expected to find positive associations of CABS1 with indicators of inflammation in nasal and lower-airway passages, as suggested by the positive association with FENO changes across multiple baselines and nasal VEGF in the academic stress study (study 3). Similarly, salivary LTB4 levels also showed a positive association with the 27-kDa band, and a tendency toward higher intensities in this band was also found for participants with asthma in one study. Both LTB4 and VEGF are mediators involved in inflammation and airway infection, orchestrating leukocyte traffic to infected sites and enhancing vessel growth to support increased perfusion. FENO levels could indicate inflammation of the airways, because a number of immune cells, such as macrophages and mast cells, secrete nitric oxide under this condition (19, 20, 52). However, given that FENO was observed in healthy participants across multiple weeks, it is more likely that FENO levels were indicative of a constitutional secretion of nitric oxide by epithelial cells, a major source of this gas in the absence of allergic processes (33). Under these conditions, nitric oxide supports innate immune functions by providing an early line of defense against pathogens (49, 80). For the CABS1 27-kDa band, the positive association with FENO changes may therefore indicate a role in infection, which would be consistent with the role of the anti-inflammatory sequence in reducing concomitants of LPS-induced lung inflammation in an animal model (71). However, associations with the WURSS, a questionnaire measure of perceived cold symptoms (3), were nonsignificant. It should also be noted that both positive and negative associations of CABS1 with inflammatory parameters and symptoms could be interpreted as a role of CABS1 in counteracting infection (negative associations could indicate that a lack of CABS1 facilitates inflammation; positive associations could mean that inflammation leads to a protective or restorative mobilization of CABS1). Thus a more definite interpretation of the significance of fluctuations of CABS1 levels in saliva or of CABS1 in lung tissues (71) during airway inflammation must come from future mechanistic and longitudinal studies. Taken together, fluctuations in both longitudinal airway nitric oxide levels and individual differences in nasal and oral mediators of inflammation are positively associated with the levels of the 27-kDa band of CABS1 in saliva.

The additional immunoreactive bands of CABS1 at molecular mass 12–20 kDa also showed evidence for responsivity to stress, with 18 kDa, in particular, showing strong elevations following the acute laboratory stressor. However, different from the associations uncovered for the ubiquitous 27-kDa band, the presence of this band was associated with psychological unresponsiveness to acute stress, since no change in negative affect from before to after the stressor was observed in participants with this band. Additionally, in studies 1 and 2, values of the PSS, a measure capturing perceived stress levels retrospectively over the past weeks, were lower in those with the 18- and 12-kDa bands than in those without additional bands. The differences were particularly pronounced in study 2, which used a longer version of the PSS, in that scores of participants with the additional bands were less than one-half of those of the other participants. It is therefore possible that additional bands provide a marker of stress resilience. The interpretation is compatible with the pattern of cardiorespiratory deactivation associated with the 27-kDa band observed in the acute stress protocol, but it is at odds with the significant positive associations observed for this band with self-reported measures of distress. It is possible that different molecular forms of CABS1 yield functionally diverging effects. Unfortunately, these observations were limited by the small number of individuals who showed the additional bands and must await replication in larger studies.

Our exploration of CABS1 in human saliva and its association with distress were limited by small sample sizes in individual studies and an overall unequal gender distribution with relatively fewer male participants. Thus further replication of our findings is needed. Our study population was also mostly composed of young undergraduate student volunteers, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings to the general population. Despite these limitations, our findings provide first evidence for the importance of psychological distress in the regulation of CABS1 and its various molecular weight forms in saliva. Although associations with endocrine, autonomic, and immune function were observed, they were modest in size and could indicate an independent role of salivary CABS1 in adaptation of the organism to a stressful environment.

Perspectives and Significance

Our results with CABS1 in humans suggest that as in rats, there is exquisite autonomic control of biologically important molecules produced by the salivary glands. CABS1 in humans and SMR1 rats are both responsive to stressful stimuli and are both processed into several molecular forms, at least some of which contain an anti-inflammatory peptide motif. Interestingly, only human—but not rat, mouse, bovine, or porcine—CABS1 contains the sequence TDIFELL (66, 71), similar to the anti-inflammatory sequence TDIFEGG, in rat SMR1. Given that in humans, not only CABS1 but also SMR3A, SMR3B, and proline-rich lacrimal 1, have homologies with the rat prohormone SMR1 (73, 74, 83), it will be intriguing to determine if these genes and their proteins are also associated with stressful stimuli. Furthermore, this raises crucial questions about the potential roles of these proteins and their processed forms in the responses to distress or potential to eustress, the locations in the body where they act, and their mechanisms of action. Presumably, the actions of CABS1 or some of these other proteins support or modulate the stress response, and whether some have a functional role in an evolutionary sense (e.g., facilitate mobilization of the organism to challenges or strengthen its defenses or resilience), have pathological significance or consequences (e.g., are indicative of pathophysiological processes or facilitate them), or might be of therapeutic value (e.g., as agents that dampen stress responses, pain processes, or inflammation) is a direction for future research.

GRANTS

Partial funding for this study was provided by Allergy, Genes and Environment (AllerGen) Network of Centres of Excellence (NCE), Canada (to A. D. Befus); the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), Canada (to A. D. Befus); and Southern Methodist University Research Council Grant URC 401608 and Gerald E. Ford Senior Research Fellowship (to T. Ritz). A. D. Befus holds the AstraZeneca Canada, Inc., Chair in Asthma Research.

DISCLOSURES

T. Ritz, C. D. St. Laurent, and A. D. Befus have a new international Patent Application Serial No. PCT/CA2017/050331 on the use of CABS1 as a biomarker of stress. The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation or in the preparation of the manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.R. and A.D.B. conceived and designed research; A.F.T., C.A.W., P.D.V., and E.R-S. performed experiments; T.R., D.R., C.D.S.L., A.F.T., C.A.W., P.D.V., E.R-S., and A.D.B. analyzed data; T.R. and A.D.B. interpreted results of experiments; T.R. C.D.S.L. and A.D.B. prepared figures; T.R., D.R., and A.D.B. drafted manuscript; T.R., D.R., C.D.S.L., P.D.V., R.J.A., E.R-S., and A.D.B. edited and revised manuscript; T.R., D.R., C.D.S.L., A.F.T., C.A.W., P.D.V., R.J.A., E.R-S., and A.D.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Iris de Guzman for assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society . ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171: 912–930, 2005. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An K, Salyer J, Kao HF. Psychological strains, salivary biomarkers, and risks for coronary heart disease among hurricane survivors. Biol Res Nurs 17: 311–320, 2015. doi: 10.1177/1099800414551164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett B, Brown R, Mundt M, Safdar N, Dye L, Maberry R, Alt J. The Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey is responsive, reliable, and valid. J Clin Epidemiol 58: 609–617, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett B, Brown R, Voland R, Maberry R, Turner R. Relations among questionnaire and laboratory measures of rhinovirus infection. Eur Respir J 28: 358–363, 2006. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00002606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernardi L, Wdowczyk-Szulc J, Valenti C, Castoldi S, Passino C, Spadacini G, Sleight P. Effects of controlled breathing, mental activity and mental stress with or without verbalization on heart rate variability. J Am Coll Cardiol 35: 1462–1469, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Bosch JA. The use of saliva markers in psychobiology: mechanisms and methods. Monogr Oral Sci 24: 99–108, 2014. doi: 10.1159/000358864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch JA, de Geus EE, Ring C, Nieuw Amerongen AV, Stowell JR. Academic examinations and immunity: academic stress or examination stress? Psychosom Med 66: 625–626, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosch JA, de Geus EJ, Veerman EC, Hoogstraten J, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Innate secretory immunity in response to laboratory stressors that evoke distinct patterns of cardiac autonomic activity. Psychosom Med 65: 245–258, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000058376.50240.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown TE, Beightol LA, Koh J, Eckberg DL. Important influence of respiration on human R-R interval power spectra is largely ignored. J Appl Physiol (1985) 75: 2310–2317, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrne ML, O’Brien-Simpson NM, Reynolds EC, Walsh KA, Laughton K, Waloszek JM, Woods MJ, Trinder J, Allen NB. Acute phase protein and cytokine levels in serum and saliva: a comparison of detectable levels and correlations in a depressed and healthy adolescent sample. Brain Behav Immun 34: 164–175, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvel P, Kervarrec C, Lavigne R, Vallet-Erdtmann V, Guerrois M, Rolland AD, Chalmel F, Jégou B, Pineau C. CLPH, a novel casein kinase 2-phosphorylated disordered protein, is specifically associated with postmeiotic germ cells in rat spermatogenesis. J Proteome Res 8: 2953–2965, 2009. doi: 10.1021/pr900082m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll D, Phillips AC, Hunt K, Der G. Symptoms of depression and cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress: evidence from a population study. Biol Psychol 75: 68–74, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: The Social Psychology of Health, edited by Spacapan S and Oskamp S Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1988, p. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24: 385–396, 1983. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contrada RJ, Krantz DS, Durel LA, Levy L, LaRiccia PJ, Anderson JR, Weiss T. Effects of beta-adrenergic activity on T-wave amplitude. Psychophysiology 26: 488–492, 1989. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, Taylor EP. Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 40: 429–434, 2001. doi: 10.1348/014466501163904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dery RE, Ulanova M, Puttagunta L, Stenton GR, James D, Merani S, Mathison R, Davison J, Befus AD. Frontline: Inhibition of allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation by the tripeptide feG: a mimetic of a neuro-endocrine pathway. Eur J Immunol 34: 3315–3325, 2004. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsythe P, Gilchrist M, Kulka M, Befus AD. Mast cells and nitric oxide: control of production, mechanisms of response. Int Immunopharmacol 1: 1525–1541, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilchrist M, McCauley SD, Befus AD. Expression, localization, and regulation of NOS in human mast cell lines: effects on leukotriene production. Blood 104: 462–469, 2004. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Global Initiative for Asthma. GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2013 version) (Online). http://www.ginasthma.org/.

- 21.Grossman P, Karemaker J, Wieling W. Prediction of tonic parasympathetic cardiac control using respiratory sinus arrhythmia: the need for respiratory control. Psychophysiology 28: 201–216, 1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1991.tb00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grossman P, Taylor EW. Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biol Psychol 74: 263–285, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruenewald TL, Kemeny ME, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Acute threat to the social self: shame, social self-esteem, and cortisol activity. Psychosom Med 66: 915–924, 2004. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000143639.61693.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellhammer DH, Wüst S, Kudielka BM. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34: 163–171, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heslegrave RJ, Furedy JJ. Sensitivities of HR and T-wave amplitude for detecting cognitive and anticipatory stress. Physiol Behav 22: 17–23, 1979. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch JA, Bishop B. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia in humans: how breathing pattern modulates heart rate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 241: H620–H629, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izawa S, Sugaya N, Kimura K, Ogawa N, Yamada KC, Shirotsuki K, Mikami I, Hirata K, Nagano Y, Nomura S. An increase in salivary interleukin-6 level following acute psychosocial stress and its biological correlates in healthy young adults. Biol Psychol 94: 249–254, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jemmott JB III, Magloire K. Academic stress, social support, and secretory immunoglobulin A. J Pers Soc Psychol 55: 803–810, 1988. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawashima A, Osman BA, Takashima M, Kikuchi A, Kohchi S, Satoh E, Tamba M, Matsuda M, Okamura N. CABS1 is a novel calcium-binding protein specifically expressed in elongate spermatids of mice. Biol Reprod 80: 1293–1304, 2009. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’—a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28: 76–81, 1993. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kline KP, Ginsburg GP, Johnston JR. T-wave amplitude: relationships to phasic RSA and heart period changes. Int J Psychophysiol 29: 291–301, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(98)00021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laguna P, Jané R, Caminal P. Automatic detection of wave boundaries in multilead ECG signals: validation with the CSE database. Comput Biomed Res 27: 45–60, 1994. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1994.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane C, Knight D, Burgess S, Franklin P, Horak F, Legg J, Moeller A, Stick S. Epithelial inducible nitric oxide synthase activity is the major determinant of nitric oxide concentration in exhaled breath. Thorax 59: 757–760, 2004. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laudenslager ML, Calderone J, Philips S, Natvig C, Carlson NE. Diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol and DHEA using a novel collection device: electronic monitoring confirms accurate recording of collection time using this device. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38: 1596–1606, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovallo WR. Do low levels of stress reactivity signal poor states of health? Biol Psychol 86: 121–128, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathison RD, Befus AD, Davison JS. A novel submandibular gland peptide protects against endotoxic and anaphylactic shock. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1017–R1023, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathison RD, Davison JS, Befus AD, Gingerich DA. Salivary gland derived peptides as a new class of anti-inflammatory agents: review of preclinical pharmacology of C-terminal peptides of SMR1 protein. J Inflamm (Lond) 7: 49–60, 2010. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathison RD, Davison JS, Metwally E. Identification of a binding site for the anti-inflammatory tripeptide feG. Peptides 24: 1221–1230, 2003. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathison RD, Davison JS, St. Laurent CD, Befus AD. Autonomic regulation of anti-inflammatory activities from salivary glands. Chem Immunol Allergy 98: 176–195, 2012. doi: 10.1159/000336513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClelland DC, Ross G, Patel V. The effect of an academic examination on salivary norepinephrine and immunoglobulin levels. J Human Stress 11: 52–59, 1985. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1985.9936739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Messaoudi M, Desor D, Nejdi A, Rougeot C. The endogenous androgen-regulated sialorphin modulates male rat sexual behavior. Horm Behav 46: 684–691, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metwally E, Befus AD, Davison JS, Mathison R. Probing for submandibular gland peptide-T receptors on leukocytes with biotinylated-Lys-[Gly](6)-SGP-T. Biochim Biophys Acta 1593: 37–44, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(02)00329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montoya P, Brody S, Beck K, Veit R, Rau H. Differential β- and α-adrenergic activation during psychological stress. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 75: 256–262, 1997. doi: 10.1007/s004210050157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris K, Kuo B, Wilkinson MD, Davison JS, Befus AD, Mathison RD. Vcsa1 gene peptides for the treatment of inflammatory and allergic reactions. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 1: 124–132, 2007. doi: 10.2174/187221307780979892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris KE, St. Laurent CD, Hoeve RS, Forsythe P, Suresh MR, Mathison RD, Befus AD. Autonomic nervous system regulates secretion of anti-inflammatory prohormone SMR1 from rat salivary glands. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C514–C524, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00214.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nater UM, Rohleder N. Salivary alpha-amylase as a non-invasive biomarker for the sympathetic nervous system: current state of research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34: 486–496, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oskis A, Clow A, Thorn L, Loveday C, Hucklebridge F. Differences between diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone in healthy female adolescents. Stress 15: 110–114, 2012. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2011.582529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillips AC, Carroll D, Evans P, Bosch JA, Clow A, Hucklebridge F, Der G. Stressful life events are associated with low secretion rates of immunoglobulin A in saliva in the middle aged and elderly. Brain Behav Immun 20: 191–197, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proud D. Nitric oxide and the common cold. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 5: 37–42, 2005. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quigley KS, Stifter CA. A comparative validation of sympathetic reactivity in children and adults. Psychophysiology 43: 357–365, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rau H. Responses of the T-wave amplitude as a function of active and passive tasks and beta-adrenergic blockade. Psychophysiology 28: 231–239, 1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1991.tb00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ricciardolo FL, Sterk PJ, Gaston B, Folkerts G. Nitric oxide in health and disease of the respiratory system. Physiol Rev 84: 731–765, 2004. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riis JL, Granger DA, DiPietro JA, Bandeen-Roche K, Johnson SB. Salivary cytokines as a minimally-invasive measure of immune functioning in young children: correlates of individual differences and sensitivity to laboratory stress. Dev Psychobiol 57: 153–167, 2015. doi: 10.1002/dev.21271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ring C, Harrison LK, Winzer A, Carroll D, Drayson M, Kendall M. Secretory immunoglobulin A and cardiovascular reactions to mental arithmetic, cold pressor, and exercise: effects of alpha-adrenergic blockade. Psychophysiology 37: 634–643, 2000. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.3750634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ritz T. Studying noninvasive indices of vagal control: the need for respiratory control and the problem of target specificity. Biol Psychol 80: 158–168, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ritz T, Dahme B. Implementation and interpretation of respiratory sinus arrhythmia measures in psychosomatic medicine: practice against better evidence? Psychosom Med 68: 617–627, 2006. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000228010.96408.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritz T, Trueba AF, Simon E, Auchus RJ. Increases in exhaled nitric oxide after acute stress: association with measures of negative affect and depressive mood. Psychosom Med 76: 716–725, 2014. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roponen M, Seuri M, Nevalainen A, Randell J, Hirvonen MR. Nasal lavage method in the monitoring of upper airway inflammation: seasonal and individual variation. Inhal Toxicol 15: 649–661, 2003. doi: 10.1080/08958370390197290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosinski-Chupin I, Rougeon F. A new member of the glutamine-rich protein gene family is characterized by the absence of internal repeats and the androgen control of its expression in the submandibular gland of rats. J Biol Chem 265: 10709–10713, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rougeot C, Messaoudi M, Hermitte V, Rigault AG, Blisnick T, Dugave C, Desor D, Rougeon F. Sialorphin, a natural inhibitor of rat membrane-bound neutral endopeptidase that displays analgesic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8549–8554, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1431850100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rougeot C, Vienet R, Cardona A, Le Doledec L, Grognet JM, Rougeon F. Targets for SMR1-pentapeptide suggest a link between the circulating peptide and mineral transport. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1309–R1320, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sackner MA, Watson H, Belsito AS, Feinerman D, Suarez M, Gonzalez G, Bizousky F, Krieger B. Calibration of respiratory inductive plethysmograph during natural breathing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 66: 410–420, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saul JP, Berger RD, Chen MH, Cohen RJ. Transfer function analysis of autonomic regulation. II. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 256: H153–H161, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scher H, Furedy JJ, Heslegrave RJ. Phasic T-wave amplitude and heart rate changes as indices of mental effort and task incentive. Psychophysiology 21: 326–333, 1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1984.tb02942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schulz SM, Ayala E, Dahme B, Ritz T. A MATLAB toolbox for correcting within-individual effects of respiration rate and tidal volume on respiratory sinus arrhythmia during variable breathing. Behav Res Methods 41: 1121–1126, 2009. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shawki HH, Kigoshi T, Katoh Y, Matsuda M, Ugboma CM, Takahashi S, Oishi H, Kawashima A. Identification, localization, and functional analysis of the homologues of mouse CABS1 protein in porcine testis. Exp Anim 65: 253–265, 2016. doi: 10.1538/expanim.15-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sherwood A, Allen MT, Fahrenberg J, Kelsey RM, Lovallo WR, van Doornen LJ. Methodological guidelines for impedance cardiography. Psychophysiology 27: 1–23, 1990. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Silkoff PE, Erzurum SC, Lundberg JO, George SC, Marczin N, Hunt JF, Effros R, Horvath I; American Thoracic Society; HOC Subcommittee of the Assembly on Allergy, Immunology, and Inflammation . ATS workshop proceedings: exhaled nitric oxide and nitric oxide oxidative metabolism in exhaled breath condensate. Proc Am Thorac Soc 3: 131–145, 2006. doi: 10.1513/pats.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skoluda N, Strahler J, Schlotz W, Niederberger L, Marques S, Fischer S, Thoma MV, Spoerri C, Ehlert U, Nater UM. Intra-individual psychological and physiological responses to acute laboratory stressors of different intensity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 51: 227–236, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Slavish DC, Graham-Engeland JE, Smyth JM, Engeland CG. Salivary markers of inflammation in response to acute stress. Brain Behav Immun 44: 253–269, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.St. Laurent CD, St Laurent KE, Mathison RD, Befus AD. Calcium-binding protein, spermatid-specific 1 is expressed in human salivary glands and contains an anti-inflammatory motif. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 308: R569–R575, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00153.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tong Y, Tar M, Davelman F, Christ G, Melman A, Davies KP. Variable coding sequence protein A1 as a marker for erectile dysfunction. BJU Int 98: 396–401, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]