Abstract

Alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) injury and apoptosis are prominent pathological features of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). There is evidence of AEC plasticity in lung injury repair response and in IPF. In this report, we explore the role of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling in determining the fate of lung epithelial cells in response to transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1). Rat type II alveolar epithelial cells (RLE-6TN) were treated with or without TGF-β1, and the expressions of mesenchymal markers, phenotype, and function were analyzed. Pharmacological protein kinase inhibitors were utilized to screen for SMAD-dependent and -independent pathways. SMAD and FAK signaling was analyzed using siRNA knockdown, inhibitors, and expression of a mutant construct of FAK. Apoptosis was measured using cleaved caspase-3 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining. TGF-β1 induced the acquisition of mesenchymal markers, including α-smooth muscle actin, in RLE-6TN cells and enhanced the contraction of three-dimensional collagen gels. This phenotypical transition or plasticity, epithelial-myofibroblast plasticity (EMP), is dependent on SMAD3 and FAK signaling. FAK activation was found to be dependent on ALK5/SMAD3 signaling. We observed that TGF-β1 induces both EMP and apoptosis in the same cell culture system but not in the same cell. While blockade of SMAD signaling inhibited EMP, it had a minimal effect on apoptosis; in contrast, inhibition of FAK signaling markedly shifted to an apoptotic fate. The data support that FAK activation determines whether AECs undergo EMP vs. apoptosis in response to TGF-β1 stimulation. TGF-β1-induced EMP is FAK- dependent, whereas TGF-β1-induced apoptosis is favored when FAK signaling is inhibited.

Keywords: apoptosis, FAK, TGF-β1, alveolar epithelial cell, differentiation

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic lung disease that results in a progressive decline in lung function and death with a mean survival of ~5 yr (36, 42). While the pathogenesis of this disease is not fully understood, there does appear to be alterations in alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) phenotype and fate. AECs in IPF show evidence of injury, endoplasmic reticulum stress, hyperplasia, and increased apoptosis. In contrast, myofibroblasts in fibroblastic foci of IPF lung tissues are resistant to apoptosis (14, 39). There is also evidence of epithelial plasticity in IPF lungs (8, 20, 29, 33, 47, 48). The extent to which this plasticity of alveolar epithelium contributes to fibrosis initiation or progression is unknown; furthermore, the mechanisms and factor(s) that control the differentiation and fate of AECs remain unclear.

The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a well-established cellular process in development and cancer metastasis; its specific role(s) in fibrogenesis of diverse organ systems such as the kidney and liver has been debated (23, 30, 33, 40, 53). EMT refers to the change of a polarized epithelial cell to a motile, often invasive, mesenchymal cell. EMT can be characterized by morphological change of an epithelial cell to an elongated, spindle-shaped cell with the loss of apical/basal polarity and gain of a front to back polarity in a three-dimensional (3-D) environment or stress fiber formation in a two-dimensional (2-D) system. This is associated with a loss of epithelial cell-specific protein expression [E-cadherin and zona occludens-1 (ZO-1)] and gain of mesenchymal protein expression [vimentin, N-cadherin, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)]. EMT can also be characterized by a functional change of an epithelial cell to a mesenchymal phenotype with the loss of cell-cell adhesions and an increase in invasiveness, contractility, or motility. The cell differentiation and plasticity of epithelial cells are integrally related to the microenvironment of the cell. Soluble factors in the cellular microenvironment, such as transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and matrix factors are critical in the transition of epithelial cells to a mesenchymal phenotype.

It has been well established that TGF-β1 is central in the pathogenesis of IPF (2–4, 27, 28, 49) and that TGF-β1 can induce apoptosis in AECs (18, 24). Whether TGF-β1 mediates fibrosis in the lung through induction of EMT is still unclear. Several papers have described TGF-β1-induced EMT during development, cancer metastasis, and kidney fibrosis. Kasai et al. (26) shed mechanistic insight into EMT in the lung by demonstrating that Smad2 silencing blocks TGF-β1-induced EMT and is, therefore, necessary for EMT to occur. FAK signaling has also been demonstrated to be important in TGF-β1-induced EMT in cancer cells (44), renal tubular epithelial cells (10), and hepatocytes (9). In this report, we characterized morphological, biochemical, and functional phenotypical changes in a rat type II alveolar epithelial cell line (RLE-6TN). As the specific role of EMT in fibrogenesis of diverse organ systems such as the kidney and liver has been debated (23, 30, 33, 40, 53), we described the observed plasticity as epithelial-myofibroblast plasticity (EMP). We demonstrate that TGF-β1-induced EMP is both SMAD3 and FAK dependent and that FAK signaling functions as a critical switch in the determination of AEC fate (EMP vs. apoptosis) in response to TGF-β1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Rat lung epithelial cells (RLE-6TN) were grown in Ham’s F-12 medium (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan UT), 10 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract, 2.5 ng/ml insulin-like growth factor-1, 2.5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), 5 μg/ml insulin, 1.25 μg/ml transferrin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, and 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin B. Cells were plated on tissue culture dishes and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2-95% air. Cells were grown to 50–60% confluence and then treated with or without TGF-β1 in serum-free medium for defined time intervals.

Reagents and antibodies.

Porcine platelet-derived TGF-β1 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Protease inhibitor cocktail set III was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The protein kinase inhibitors PD98059, SB600125, Y27632, SU6656, and PF573228 were obtained from Calbiochem. The Alk-5 inhibitor SB431542 was obtained from Tocris (Bristol, UK). Antibodies for immunofluorescence and Western blotting studies were obtained from commercial sources: α-smooth muscle actin was from DAKO (Carpenteria, CA); ZO-1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin, phosphorylation-specific antibody to phospho-Y-397 FAK, and total FAK were from Invitrogen; and SMAD3, cleaved caspase-3, total caspase, and α-tubulin were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); and GAPDH was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma, Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Western immunoblotting and immunofluorescent staining.

Cells were prepared in RIPA buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, and Western blotting was performed as previously described (6, 38). For immunofluorescent studies, cells grown on 35-mm cell culture dishes were initially rinsed with cold PBS solution and then fixed in 50% methanol/acetone solution for 10–15 min. Cells were then washed three times in PBS before permeabilization and after each subsequent step. Permeabilization was performed in buffer consisting of 0.1% Triton in 50 mM PIPES (pH 7.0), 90 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 0.5 MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 75 mM KCl for 15 s at room temperature. Culture dishes were sequentially incubated with blocking buffer, primary antibodies, and secondary antibodies, each for 60 min at room temperature, or with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) stain per manufacturer’s instructions (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) (13). Culture dishes were then visualized and photographed using a Zeiss fluorescent microscope.

Collagen gel contraction assay.

The assays were performed as previously described (5). Briefly, RLE-6TN cells were grown to 100% confluence in Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were then trypsinized, resuspended, and counted using a hemocytometer. Cells (400,000/ml), serum-free F-12 media, and rat tail type I collagen (Sigma) were combined in a 2:1:1 ratio to achieve a final concentration of collagen of 0.75 mg/ml. The collagen/cell suspension was then transferred in 1-ml aliquots to a 24-well culture plate, and gels were allowed to polymerize at 37°C for 1 h. After polymerization, F-12 media with 10% FBS were added to the wells. After 12 h of incubation, the cells in the collagen gels were treated with 2.5 ng/ml of TGF-β1. Immediately after addition of the TGF-β1, the gels were detached from the sides of the dish using a sterile pipette. Gels were observed and pictured at various time points. The area of the gels was calculated using the ImageJ software downloaded from the National Institutes of Health software website.

Generation of stable transfected cell lines.

RLE-6TN cells were transfected with the mammalian expression plasmid pcDNA, pcDNA-HA-FAK wild type (HA tagged), and pcDNA-HA-FAK-Y397F (HA-tagged FAK mutant, in which the tyrosine 397 was replaced by phenylalanine) using Fugene-6 transfection reagent (Roche), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasmid constructs were a gift from Dr. Ken Yamada, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (Bethesda, MD). RLE-6TN cells were incubated with transfection reagent and DNA in serum-free Ham’s F-12 for 10–12 h before introducing 10% serum for 16–20 h. Stable transfectants were isolated by selection in media containing geneticin.

RNA interference.

For in vitro RNA interference (RNAi) experiments, we transfected cells with single duplexes targeting SMAD3 (200 μM) or nontargeting control siRNA (200 nM) purchased from Dharmacon RNAi Technologies (Lafayette, CO) using Lipofectamine-2000 reagent (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s protocol (15).

Statistical analysis.

All data are summarized as means ± SE. All experiments were repeated at least three times with multiple replicates. For the statistical analysis, a Student t-test was used to compare two experimental groups for the potential differences. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TGF-β1 induces EMP in rat lung epithelial cells (RLE-6TN).

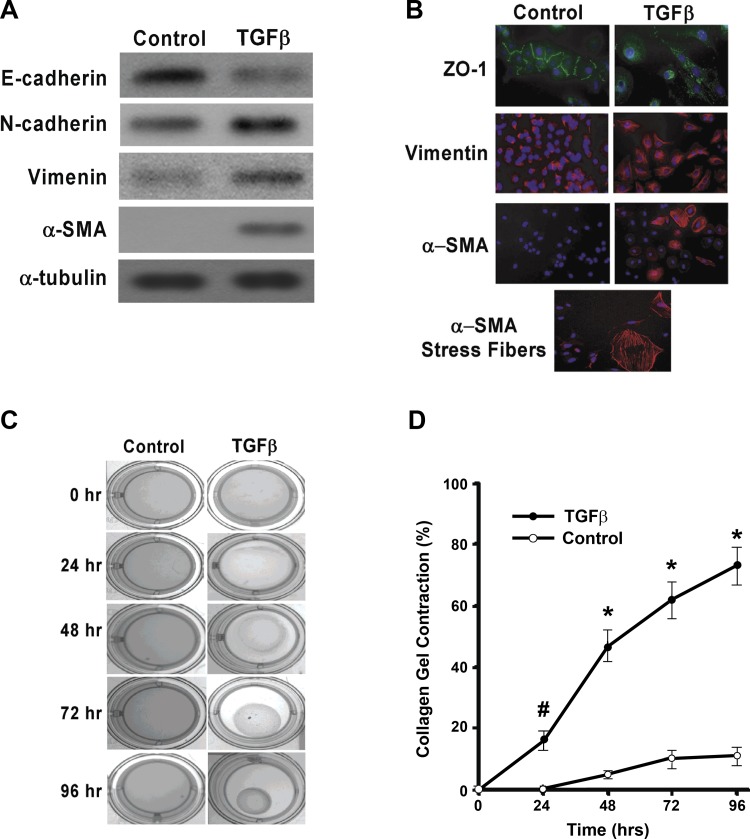

EMT has been demonstrated in a number of tissues (reviewed in Refs. 1, 7, 16). RLE-6TN cells have been used as a model of EMT in cell culture (48). We characterized biochemical, morphological, and functional changes in RLE-6TN cells in response to TGF-β1. TGF-β1 induced a downregulation of the epithelial-specific cadherin E-cadherin and an upregulation of the mesenchymal cadherin N-cadherin when analyzed by Western immunoblots (Fig. 1A). Immunofluorescent staining showed loss of ZO-1 on the cell surface in TGF-β1-treated cells (Fig. 1B, top). Increased expression of vimentin was also noted in whole cell lysates (Western blot analysis, Fig. 1A) and in individual cells (by immunofluorescence staining; Fig. 1B, middle). The most notable change was in the neo-induction of α-SMA, which was not observed at baseline but was markedly induced by TGF-β1 (Figs. 1, A and B, bottom). Interestingly, the induction of α-SMA-expressing stress fibers in epithelial cells indicating a transition to a myofibroblast phenotype was seen only in a subset of cells (Fig. 1B, bottom). These data indicate that TGF-β1 is capable of inducing a myofibroblast-like phenotype in RLE-6TN cells, at least in a subset of cells, in response to TGF-β1 stimulation.

Fig. 1.

Transforming growth factor- β1 (TGF-β1) can induce epithelial-myofibroblast plasticity (EMP) and functional phenotypical change in RLE-6TN cells. RLE-6TN cells were serum starved for 24 h then treated without or with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 48 h (A and B) or indicated time (C and D). We confirm that RLE-6TN cells undergo TGF-β1-induced EMP by both protein analysis and immunohistochemistry staining. A: Western blotting demonstrates the loss of the epithelial cell marker E-cadherin and increase in mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin and the myofibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). B: immunohistochemical staining demonstrates a zona occludens-1 (ZO-1) downregulation, increased vimentin expression, increased α-SMA expression, and the development of intermediate filaments. C: RLE-6TN cells were grown in a 3-dimensional (3-D) collagen gel matrix and treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml). Immediately after treatment the sides of the gel were detached from the plate and contraction was measured at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. TGF-β1 treatment of RLE-6TN cells induces significant collagen contraction at indicated time points demonstrating differentiation into a functional mesenchymal phenotype. Pictorial representation of TGF-β1 induced collagen contraction at each time point. D: percent gel contraction relative to time 0 h in the control and TGF-β1-treated cells. All experiments were repeated 3-4 times, and representative images are shown. #P < 0.01 and *P < 0.001 for TGF-β1-treated cells vs. controls at indicated time points.

Myofibroblasts are functionally defined by their ability to mediate tissue contraction (21, 41). Based on our findings of a biochemical and morphological transition to myofibroblast-like cells, we examined whether TGF-β1 influenced the contractility of RLE-6TN cells embedded in 3-D collagen gels. TGF-β1 stimulation of cells enhanced collagen gel contractility at 48, 72, and 96 h (Fig. 1, C and D). These studies indicate the TGF-β1 is capable of inducing a biochemical, morphological, and functional phenotypical change in RLE-6TN cells to myofibroblast-like cells.

TGF-β1-induced EMP is dependent on FAK.

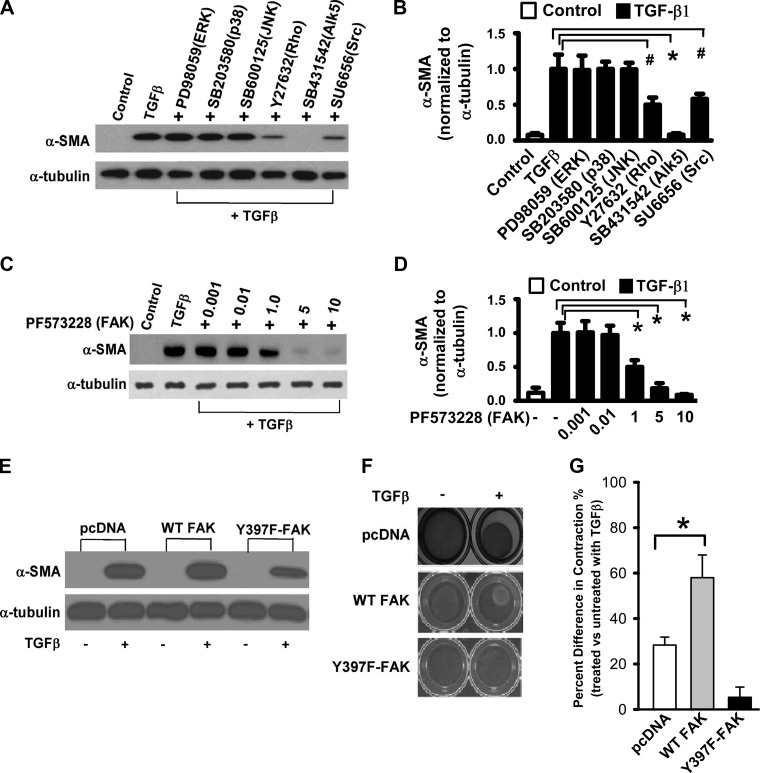

EMT has been reported to be mediated by SMAD-dependent and -independent signaling (50). To examine the pathways involved in TGF-β1-induced α-SMA expression in RLE-6TN cells, we utilized pharmacological inhibitors of protein kinases to determine their potential role(s). Treatment of cells with protein kinase inhibitors of the MAPK pathways (ERK, p38, and JNK) had no effect on TGF-β1-induced α-SMA expression, whereas pharmacological inhibitors of TGF-β1 type I receptor kinase (ALK-5), Rho kinase, Src family kinase(s) (Fig. 2, A and B), and FAK (Fig. 2, C and D) inhibited this response. α-SMA expression was completely inhibited by blocking the Alk5 (TGFβ type 1 receptor kinase) and FAK signaling and partially inhibited by blocking the Rho kinase and Src signaling pathways. To further explore the potential role of FAK in this response, we generated stable transfectants overexpressing mutant FAK (Y397F-FAK, substitution of tyrosine 397 with phenylalanine). Cells expressing mutant FAK demonstrated lower levels of α-SMA induction in comparison to control plasmid (pcDNA; Fig. 2E). To determine if FAK is required for the TGF-β1-induced contractile responses, the effects of TGF-β1 on cells transfected with Y397F-FAK were evaluated in 3-D collagen gels. Mutation of FAK at the Y-397 site abrogated the contractile responses to TGF-β1 (Fig. 2, F and G). These data support an essential role for FAK signaling in TGF-β1-induced EMP.

Fig. 2.

TGF-β1-induced EMP can be inhibited by blocking the TGF-β receptor 1 (Alk5) and FAK pathways in RLE-6TN cells. A: RLE-6TN cells were grown to 50–60% confluence and treated with TGF-β1 alone or with the following protein kinase inhibitors (in mM): 20 PD98059, 6 SB203580, 1 SB600125, 15 Y27632, 10 SB431542, and 10 SU6656. Cells were then lysed at 48 h after treatment and Western blot analysis was performed for α-SMA. B: densitometry analysis of experiments in A. #P < 0.05 and *P < 0.01. C: RLE-6TN cells were grown as A, treated with TGF-β1 alone or with PF573228 (FAK inhibitor) at indicated concentration (µM). Cells were then lysed at 48 h after treatment and Western blot analysis was performed for α-SMA. D: densitometry analysis of experiments in C. *P < 0.01. E: RLE-6TN cells were grown to 50% confluence and were then transfected with plasmids overexpressing pcDNA (control), wild-type (WT) FAK, and Y397F-FAK mutant in a dominant negative fashion. Stably transfected cell lines were then serum starved then grown in the presence and absence of TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 48 h. Western blot analysis for α-SMA demonstrates cells transfected with Y397F-FAK transfects had decreased α-SMA expression following TGF-β1 treatment. F: RLE-6TN cells grown in a 3-D collagen gel matrix in the presence and absence of TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 48 h. Cell lines transfected with Y397F-FAK mutant were unable to contract the collagen gel in the presence of TGF-β1. G: quantification of collagen gel matrix contraction. All experiments were repeated 3-4 times, and representative images are shown. *P < 0.01.

TGF-β1-induced FAK phosphorylation is dependent on SMAD3 signaling.

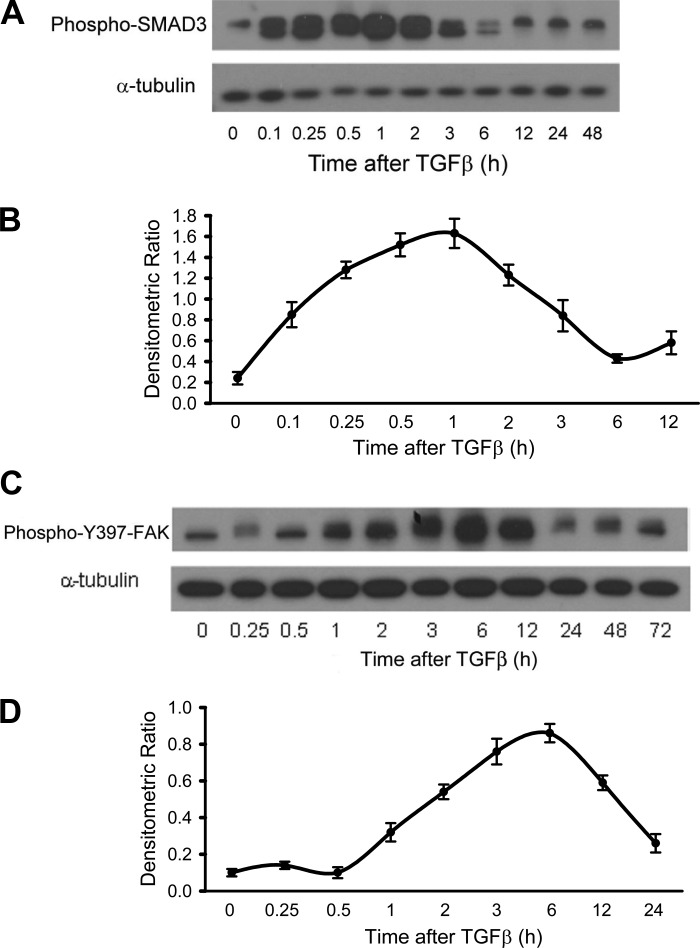

TGF-β1 is known to activate SMAD-dependent and -independent signaling pathways (50). To determine the relationship between SMAD and FAK activation, we first examined the kinetics of the activation of these pathways. SMAD3 was activated within 5 min, peaked at ~1 h, and returned to basal levels 6 h following TGF-β1 stimulation (Fig. 3, A and B). In comparison, FAK activation was relatively delayed at 1 h, peaking at 6 h before returning to baseline levels over 24 h following TGF-β1 stimulation (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3.

Time course of SMAD3 and FAK activation after TGF-β1 stimulation. RLE-6TN cells were grown to 50–60% confluence and serum starved for 24 h. They were then treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml), and Western blot analysis was performed for phophorylated SMAD3 (A) and phophorylated Y397 (C) of FAK for various time points up to 72 h. B and D: densitometric ratio for pSMA3 (B) and pFAK (D). Phosphorylated SMAD3 begins to increase at immediately after treatment, peaks around 1 h posttreatment, and returns to baseline by 6 h. Phosphorylated FAK does not begin to increase until ~1 h after treatment, peaks at 6 h posttreatment, and does not return to baseline until 24 h after treatment. All experiments were repeated 3 times, and representative images are shown.

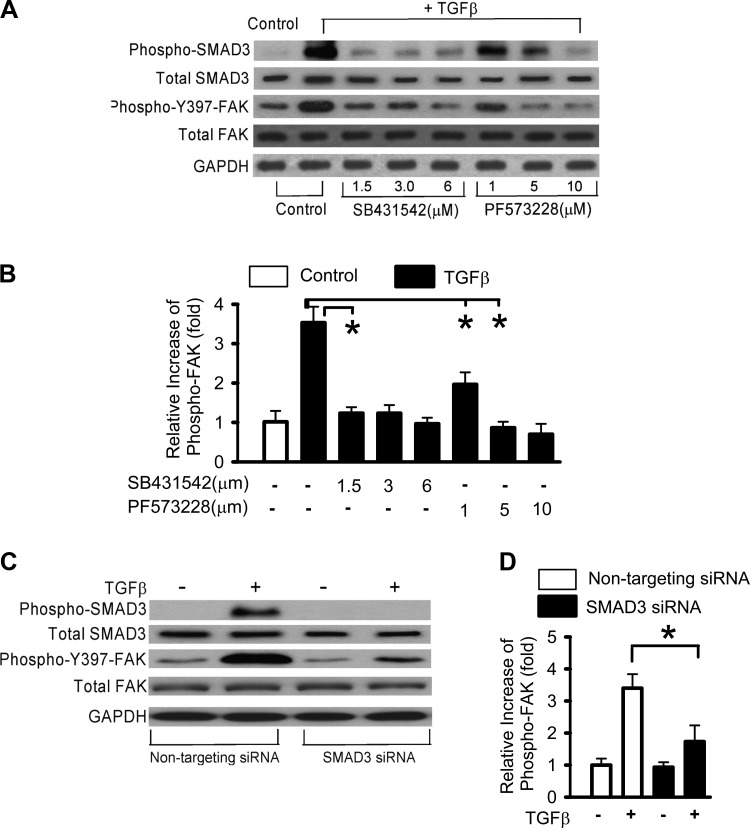

These kinetic studies suggest the possibility that SMAD3 activation may be necessary for activation of FAK by TGF-β1. Therefore, we studied the effects of pharmacological inhibitors of SMAD signaling (the TGF-β1 type I receptor kinase/ALK5 inhibitor SB431542) and FAK (PF573228) on the activation of these pathways by TGF-β1. SB431542, at a low dose (1.5 µM), inhibited TGF-β1-induced SMAD3 and FAK phosphorylation (Fig. 4, A and B). PF573228 inhibited TGF-β1-induced FAK phosphorylation at 5 µM and, at this dose, partially blocked SMAD3 phosphorylation. A more complete inhibition of SMAD3 activation was observed at a higher dose of PF573228 (10 µM; Fig. 4A). This suggests that FAK signaling is dependent on ALK5/SMAD3 signaling and also there is likely a feedback loop between FAK and SMAD3 signaling. This could potentially be through contraction-mediated liberation of more active TGF- β that is lost in the presence of FAK inhibition as shown in Fig. 2F. Additionally, we performed SMAD3 siRNA knockdown studies that confirmed that TGF-β1-induced FAK activation is dependent on SMAD3 (Fig. 4, C and D). It has been shown that siRNA targeting Smad3 prevented TGF-β1-induced FAK phosphorylation (22). Together, these data demonstrate that TGF-β1-induced FAK activation is dependent on ALK5 signaling via SMAD3.

Fig. 4.

TGF-β-induced FAK activation is SMAD3 dependent. RLE-6TN cells were grown to 50–60% confluence and serum starved for 24 h. A: cells were then treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) in the presence of pharmacological inhibitors of SMAD (SB431542) and FAK (PF573228) signaling for 48 h. Control includes the same concentration vehicle. Western blots were performed for SMAD3 and FAK autophosphorylation. B: relative densitometry was used to examine the TGF-β1-induced FAK activation in A. The data represent the relative level of phospho-397-FAK vs. total FAK ratio (relative to without TGF-β1). C: cells were transfected with either nontargeting siRNA or SMAD3 siRNA and treated without or with TGF-β1 for 48 h. Western blot analysis was done for phosphorylated SMAD3 and FAK. D: relative densitometry was used to examine the TGF-β1-induced FAK activation in C. SB431542 or SMAD3 siRNA blocked both SMAD3 autophosphorylation as well as FAK autophosphorylation in TGF-β1-treated cells. All experiments were repeated 3 times, and representative images are shown. *P < 0.01.

TGF-β1 treatment of lung epithelial cells induces both EMP and apoptosis under the same culture conditions.

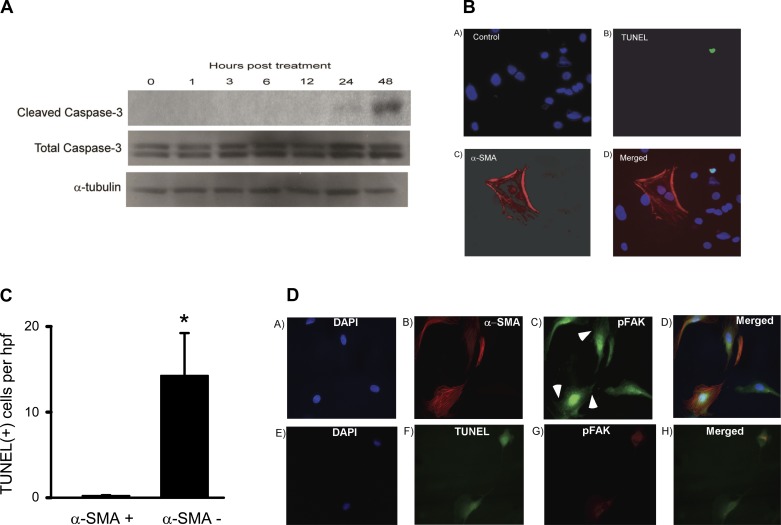

TGF-β1 has been reported to induce apoptosis of a number of epithelial cell types (17, 18, 51, 52). We determined whether TGF-β1, under the same conditions that induced EMP, was capable of inducing apoptosis. We observed a time-dependent induction of apoptosis, as evidenced by expression of cleaved caspase-3 in RLE-6TN cells treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml); this effect had an apparent peak at 48 h (Fig. 5A). Immunofluorescent cell staining by TUNEL showed that, similar to EMP, only a subset of cells undergo apoptosis in response to TGF-β1 (Fig. 5B). Based on the observations that TGF-β1 induces both EMP and/or apoptosis in only a subset of cells, we examined the colocalization of the myofibroblast marker α-SMA and apoptotic cells with TUNEL staining. Interestingly, apoptosis of α-SMA-expressing cells was relatively rare, while apoptosis (TUNEL staining) of non-α-SMA cells was readily identifiable (Fig. 5B, representative staining section); quantification of the number of cells undergoing apoptosis and acquisition of EMP was done by counting the number of cells in five high-power fields (hpf) that were either α-SMA positive, TUNEL positive, or both. There were 73 cells that were TUNEL positive and α-SMA negative or an average of 15 cells/hpf, whereas there was only 1 cell seen that was both TUNEL positive and α-SMA positive or an average of 0.2 cells/hpf (Fig. 5C). Immunofluorescent costain of α-SMA and phospho-FAK demonstrated that FAK was activated in cells obtained that were of the mesenchymal phenotype (containing α-SMA-positive fibers) and the activated FAK (phospho-FAK) was located on prominent focal adhesions (Fig. 5, C and D, arrowheads). Immunofluorescent costain of TUNEL and phospho-FAK demonstrated that FAK activation was minimal, and importantly there was no phospho-FAK at focal adhesions (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that there is a heterogeneous response of RLE-6TN cells to TGF-β1; importantly, cells that acquire features of EMP are relatively resistant to apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

TGF-β1 induces apoptosis and EMP in RLE-6TN cells but not in the same cell at the same time. A: TGF-β1 induces apoptosis in RLE-6TN cells. RLE-6TN cells were grown to 50–60% confluence and serum starved for 24 h. They were then treated with TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) for 48 h, and Western blot analysis for cleaved caspase-3 was performed at various time points. TGF-β1 treatment induced cleaved caspase-3, which peaked at 48 h posttreatment. B: RLE-6TN cells were grown to 50–60% confluence in 35-mm tissue culture dishes. They were then treated with TGFβ-1 (2.5 ng/ml) in serum-free media for 72 h. They were then stained with antibodies to α-SMA and with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining. BA–BD: representative fields with control (BA), TUNEL staining (BB), α-SMA staining (BC), and merged images (BD). C: then, 5 high power magnification fields (hpf) were examined for the number of α-SMA-positive cells as described in B; the number of TUNEL-positive cells and the number of cells that were positive for both. In an average of five hpf fields, there were 73 α-SMA(−)/TUNEL(+) cells and only 1 TUNEL(+)/α-SMA(+) cell. *P < 0.01. D: cells were treated as described in B. Immunofluorescent costain of α-SMA and pY397-FAK (pFAK) (DA–DD) showed that FAK was activated and located on prominent focal adhesions (arrowheads) in cells containing α-SMA-positive fibers. Immunofluorescent costain of TUNEL and phospho-FAK (DA–DD) showed that TUNEL-positive cells did not have the active FAK and focal adhesions. All experiments were repeated 3-4 times, and representative images are shown.

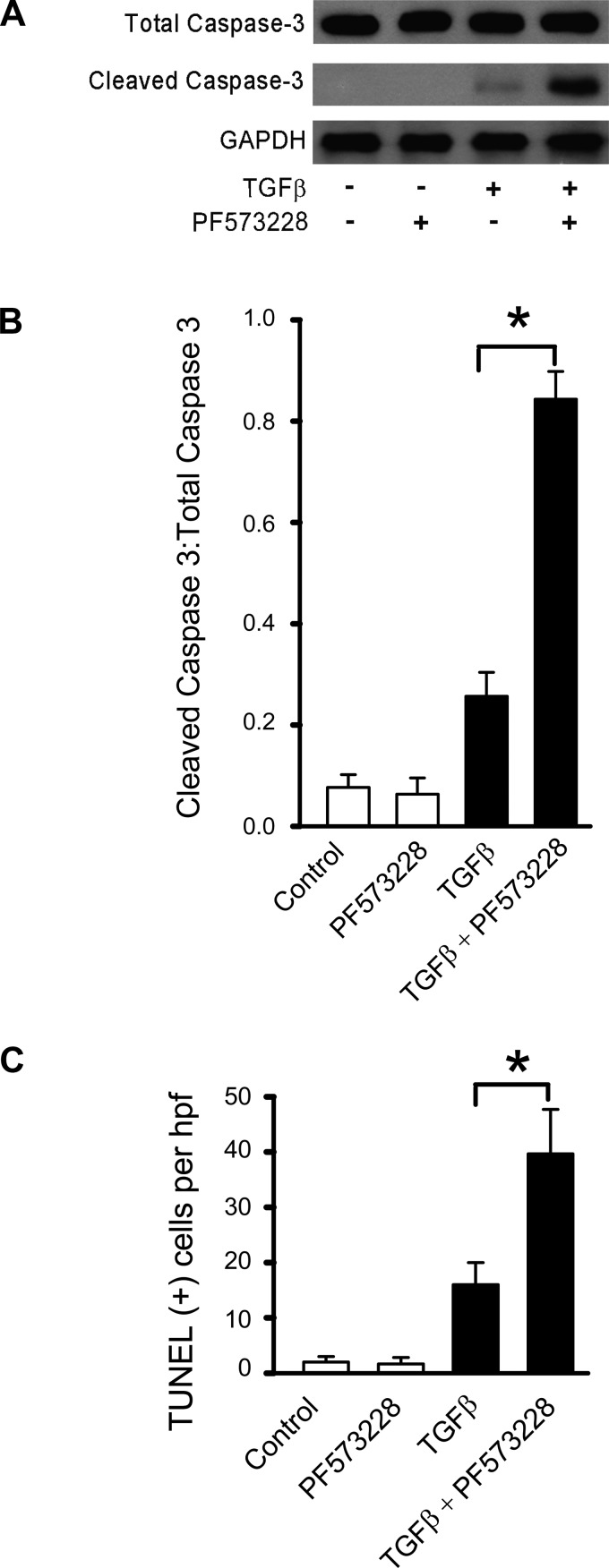

FAK signaling promotes TGF-β-induced EMP and protects from apoptosis.

Since TGF-β1 induced both EMP and apoptotic fates in lung epithelial cells, we hypothesize that blockade of FAK signaling will not only abrogate EMP but shift the fate of these cells toward apoptosis. RLE-6TN cells were treated with an inhibitor of FAK (PF573228, 5 µM) for 30 min followed by TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) before assessment of apoptosis. TGF-β1 alone induced a small increase in cleaved caspase-3 expression, as assessed in whole cell lysates; however, TGF-β1 in the presence of PF573228 induced a marked increase in apoptosis (Fig. 6A; densitometric ratio of cleaved caspase 3:total caspase is shown in Fig. 6B). In addition, TGF-β1 in the presence of PF573228 significantly increased the number of TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that blockade of FAK signaling shifts the fate of cells from an EMP fate to one that undergoes apoptosis in response to TGF-β1.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of FAK signaling increases TGFβ-1-induced apoptosis. RLE-6TN cells were grown to 50–60% confluence in 35-mm tissue culture dishes. They were then treated with TGFβ-1 (2.5 ng/ml) in serum-free media for 72 h, in the presence and absence of pharmacological inhibitors to FAK (PF573228; 5 µM) signaling. A: Western blot analysis for total and cleaved caspase-3 was performed. B: densitometric measures (of A) support that inhibition of SMAD signaling has no effect on TGFβ-1-induced caspase-3 cleavage, but inhibition of FAK signaling increases TGFβ-1-induced cleaved caspase-3 by ~3-fold (data corrected for GAPDH and represented as the ratio of cleaved caspase-3:total caspase 3). C: cells in A were subjected to TUNEL staining, and TUNEL-positive cells were quantified as in Fig. 5. All experiments were repeated 3-4, times and representative images are shown. *P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

TGF-β1 signaling has been implicated in almost every human fibrotic disease examined, as well as in a number of experimental animal models (2–4, 27, 28). However, targeting this cytokine or its receptor(s) may prove deleterious due to its well-recognized homeostatic roles in immunomodulation and tumor suppression (35, 43). A clearer understanding of the mechanisms of the actions of TGF-β on target cells, including AECs, may inform safer and more effective therapeutic strategies for fibrotic disorders. AECs in IPF are best described as “under stress,” with varying degrees of apoptosis and transition to the mesenchymal phenotype (25, 37). Interestingly, TGF-β1 is known to mediate both mesenchymal phenotype transition (46) and apoptosis (35) in various types of epithelial cells. However, few studies have reconciled these seemingly dichotomous fates in response to TGF-β1.

In this study, we evaluated the phenotype and fates of AECs in response to TGF-β1 using a cell culture model of rat type II alveolar cells (RLE-6TN). We observed an epithelial-myofibroblast plasticity response (termed EMP in this article), based on the observations of prominent actin stress fiber formation, enhanced contractility in 3-D collagen gels, and features associated with myofibroblast differentiation. Interestingly, EMP was seen in only a subset of cells that evaded apoptotic responses to the same cytokine, TGF-β1. This heterogeneity in responses to TGF-β1 allowed us to probe into potential mechanisms that determine an EMP vs. an apoptotic fate of AECs.

First, our studies reproduce several reports that support the capacity of TGF-β1 to mediate a mesenchymal or a mesenchymal-like transition response in epithelial cells, including RLE-6TN (29, 48). However, heterogeneity in TGF-β1 responses has not been previously described or studied, to our knowledge, in any of the previous reports. Such heterogeneity is easily missed when measurements are based on analyses of whole cell preparations. Indeed, we did reproduce previously reported observations of a downregulation of the epithelial cell marker E-cadherin and an upregulation the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin, vimentin, and α-SMA. Loss of ZO-1 suggests potential cell-cell adhesion disassembly. Additionally, TGF-β1 induced the formation of contractile stress fibers in a subset of AECs, likely contributing to the observed increases in cell contractility of 3-D collagen matrices in the current study.

TGF-β1 signaling may be mediated by both SMAD-dependent and SMAD-independent pathways that include Rho kinases, Src-family kinases, and FAK (11, 12, 34). In an initial screen using pharmacological protein kinase inhibitors, we identified FAK signaling as a noncanonical pathway that is essential for EMP induced by TGF-β1. With the use of a combination of pharmacological and genetic strategies, it was determined that FAK signaling mediates TGF-β1-induced EMP in AECs. Furthermore, we determined that TGF-β1-induced FAK was, at least partially, dependent on ALK5/SMAD3 based on the following observations: 1) FAK activation is temporally delayed relative to the early activation of SMAD3; 2) an ALK5 inhibitor that inhibits SMAD3 also inhibits FAK; and 3) SMAD3 siRNA knockdown blocks TGF-β1-induced FAK activation.

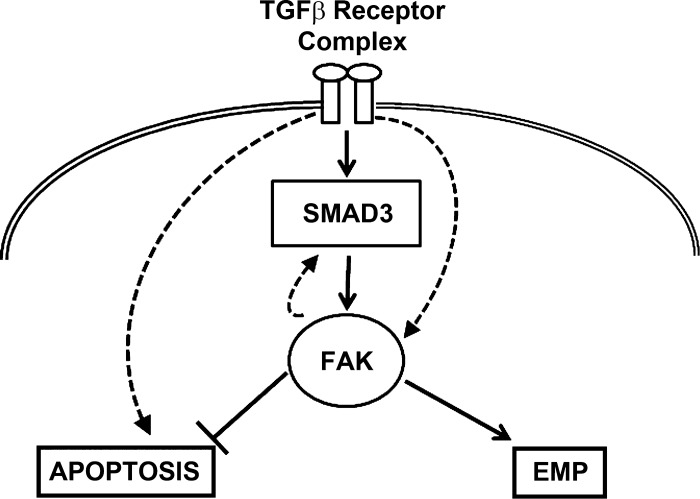

Following on the observations that TGF-β1-induced EMP occurs in only a subset of AECs, we sought to determine whether TGF-β1 was capable of inducing apoptosis of cells that fail to demonstrate EMP. Our data strongly suggest that apoptosis and EMP are dichotomous responses that, strikingly, do not overlap; i.e., TGF-β1-induced apoptosis is almost exclusively in the subset of cells that do not demonstrate EMP and, as a corollary, cells demonstrating EMP appear to resist apoptosis. This divergence in signaling and dichotomous fates are supported by the finding that cells shift from EMP to apoptosis when FAK signaling is blocked (Fig. 7, schematic summary). It has been shown that AKT pathway plays a critical survival role in response to TGF-β1 stimulation (22, 24) and that FAK promotes and activates phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, an important upstream mediator of AKT pathway (19, 31, 32). Active FAK inhibits apoptosis in fibroblasts and epithelial cells (54). A recent publication links substrate-mediated FAK activation to AEC susceptibility to TGF-β1-induced apoptosis (45). We speculate that FAK may regulate the survival process through the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT pathway in response to TGF-β1.

Fig. 7.

Schematic of the fates of alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) in response to TGF-β1. The data suggest that TGFβ-1 signaling through FAK is SMAD3 dependent. There is likely a feedback loop between FAK and SMAD3 signaling. There are likely other SMAD3-independent pathways that lead to TGFβ-1-induced FAK activation that are beyond the scope of this article. When FAK is autophosphorylated, it induces a phenotypical change in AECs to a more mesenchymal phenotype. When FAK signaling is inhibited, then there is a switch to a more apoptotic phenotype for TGFβ-1-treated AECs. This is likely through SMAD3-independent pathways that lead to apoptosis.

Several pharmaceutical companies have attempted to develop TGF-β receptor/ALK5 inhibitors for the treatment of fibrotic diseases and cancer metastasis. However, potential benefits of such approaches may be ineffective due to the known homeostatic roles of TGF-β as an immunomodulator (43) and tumor suppressor (35). Targeting non-SMAD pathways or further downstream targets may prove to be safer and potentially more beneficial. In our studies, we identified FAK as one such downstream target in TGF-β1 signaling. RLE-6TN cells are immortalized rat lung epithelial cells; therefore, the current study has some limitations including the concern that some of RLE-6TN cells can undergo spontaneous EMT. Future studies using the primary lung epithelial cells will provide further evidence about the signaling pathways involved. Nonetheless, our studies suggest that therapeutic strategies targeting FAK signaling suppress EMP, and meanwhile the FAK signaling potentiates AEC with the EMP phenotype change for apoptosis. Whether this will ultimately prove effective as an anti-fibrotic therapeutic strategy may depend on evolving insights into the relative roles of mesenchymal or mesenchymal-like transition and apoptosis in fibrotic diseases such as IPF, as well on the relative dependence of AECs and myofibroblasts on FAK signaling for survival.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-067967, P50-HL-107181, R01-HL-085324, and R01-HL-127338 and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I.S., P.C., M.W., X.K.Z., N.B., A.R.K., M.H., and R.V. performed experiments; Q.D., T.R.L., P.C., L.H., M.H., J.C.H., R.V., and V.J.T. analyzed data; Q.D., T.R.L., P.C., X.K.Z., L.H., J.C.H., and V.J.T. interpreted results of experiments; Q.D., I.S., T.R.L., P.C., and J.C.H. prepared figures; Q.D., T.R.L., and V.J.T. drafted manuscript; Q.D., T.R.L., P.C., X.K.Z., Y.Z., J.C.H., and V.J.T. edited and revised manuscript; Q.D., I.S., T.R.L., P.C., M.W., X.K.Z., N.B., A.R.K., L.H., M.H., Y.Z., J.C.H., R.V., and V.J.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of L. Hecker: Div. of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724; and Southern Arizona Veterans Affairs Health Care System (SAVAHCS), Tucson, AZ 85723.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bi WR, Yang CQ, Shi Q. Transforming growth factor-β1 induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatic fibrosis. Hepatogastroenterology 59: 1960–1963, 2012. doi: 10.5754/hge11750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med 331: 1286–1292, 1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Border WA, Ruoslahti E. Transforming growth factor-beta in disease: the dark side of tissue repair. J Clin Invest 90: 1–7, 1992. doi: 10.1172/JCI115821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broekelmann TJ, Limper AH, Colby TV, McDonald JA. Transforming growth factor beta 1 is present at sites of extracellular matrix gene expression in human pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 6642–6646, 1991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai GQ, Chou CF, Hu M, Zheng A, Reichardt LF, Guan JL, Fang H, Luckhardt TR, Zhou Y, Thannickal VJ, Ding Q. Neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) is critical for formation of α-smooth muscle actin filaments during myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L692–L702, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00390.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai GQ, Zheng A, Tang Q, White ES, Chou CF, Gladson CL, Olman MA, Ding Q. Downregulation of FAK-related non-kinase mediates the migratory phenotype of human fibrotic lung fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res 316: 1600–1609, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman HA. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in pulmonary fibrosis. Annu Rev Physiol 73: 413–435, 2011. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilosi M, Zamò A, Doglioni C, Reghellin D, Lestani M, Montagna L, Pedron S, Ennas MG, Cancellieri A, Murer B, Poletti V. Migratory marker expression in fibroblast foci of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 7: 95, 2006. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicchini C, Laudadio I, Citarella F, Corazzari M, Steindler C, Conigliaro A, Fantoni A, Amicone L, Tripodi M. TGFbeta-induced EMT requires focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling. Exp Cell Res 314: 143–152, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng B, Yang X, Liu J, He F, Zhu Z, Zhang C. Focal adhesion kinase mediates TGF-beta1-induced renal tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in vitro. Mol Cell Biochem 340: 21–29, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 425: 577–584, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding Q, Gladson CL, Wu H, Hayasaka H, Olman MA. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-related non-kinase inhibits myofibroblast differentiation through differential MAPK activation in a FAK-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 283: 26839–26849, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803645200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding Q, Grammer JR, Nelson MA, Guan JL, Stewart JE Jr, Gladson CL. p27Kip1 and cyclin D1 are necessary for focal adhesion kinase regulation of cell cycle progression in glioblastoma cells propagated in vitro and in vivo in the scid mouse brain. J Biol Chem 280: 6802–6815, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding Q, Luckhardt T, Hecker L, Zhou Y, Liu G, Antony VB, deAndrade J, Thannickal VJ. New insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Drugs 71: 981–1001, 2011. doi: 10.2165/11591490-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding Q, Stewart J Jr, Olman MA, Klobe MR, Gladson CL. The pattern of enhancement of Src kinase activity on platelet-derived growth factor stimulation of glioblastoma cells is affected by the integrin engaged. J Biol Chem 278: 39882–39891, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304685200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fragiadaki M, Mason RM. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal fibrosis - evidence for and against. Int J Exp Pathol 92: 143–150, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gressner AM, Lahme B, Mannherz HG, Polzar B. TGF-beta-mediated hepatocellular apoptosis by rat and human hepatoma cells and primary rat hepatocytes. J Hepatol 26: 1079–1092, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagimoto N, Kuwano K, Inoshima I, Yoshimi M, Nakamura N, Fujita M, Maeyama T, Hara N. TGF-beta 1 as an enhancer of Fas-mediated apoptosis of lung epithelial cells. J Immunol 168: 6470–6478, 2002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanks SK, Ryzhova L, Shin NY, Brábek J. Focal adhesion kinase signaling activities and their implications in the control of cell survival and motility. Front Biosci 8: d982–d996, 2003. doi: 10.2741/1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harada T, Nabeshima K, Hamasaki M, Uesugi N, Watanabe K, Iwasaki H. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human lungs with usual interstitial pneumonia: quantitative immunohistochemistry. Pathol Int 60: 14–21, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmoulière A, Varga J, De Wever O, Mareel M, Gabbiani G. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am J Pathol 180: 1340–1355, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horowitz JC, Rogers DS, Sharma V, Vittal R, White ES, Cui Z, Thannickal VJ. Combinatorial activation of FAK and AKT by transforming growth factor-beta1 confers an anoikis-resistant phenotype to myofibroblasts. Cell Signal 19: 761–771, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 110: 341–350, 2002. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ju EM, Choi KC, Hong SH, Lee CH, Kim BC, Kim SJ, Kim IH, Park SH. Apoptosis of mink lung epithelial cells by co-treatment of low-dose staurosporine and transforming growth factor-beta1 depends on the enhanced TGF-beta signaling and requires the decreased phosphorylation of PKB/Akt. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 328: 1170–1181, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kage H, Borok Z. EMT and interstitial lung disease: a mysterious relationship. Curr Opin Pulm Med 18: 517–523, 2012. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283566721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasai H, Allen JT, Mason RM, Kamimura T, Zhang Z. TGF-beta1 induces human alveolar epithelial to mesenchymal cell transition (EMT). Respir Res 6: 56, 2005. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil N, O’Connor RN, Flanders KC, Unruh H. TGF-beta 1, but not TGF-beta 2 or TGF-beta 3, is differentially present in epithelial cells of advanced pulmonary fibrosis: an immunohistochemical study. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 14: 131–138, 1996. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.2.8630262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalil N, O’Connor RN, Unruh HW, Warren PW, Flanders KC, Kemp A, Bereznay OH, Greenberg AH. Increased production and immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor-beta in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 5: 155–162, 1991. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/5.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim KK, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, Robillard L, Galvez MG, Brumwell AN, Sheppard D, Chapman HA. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 13180–13185, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605669103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, Thompson EW. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol 172: 973–981, 2006. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsons JT. Focal adhesion kinase: the first ten years. J Cell Sci 116: 1409–1416, 2003. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng X, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase: from in vitro studies to functional analyses in vivo. Curr Protein Pept Sci 12: 52–67, 2011. doi: 10.2174/138920311795659452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rock JR, Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Xue Y, Harris JR, Liang J, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Multiple stromal populations contribute to pulmonary fibrosis without evidence for epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: E1475–E1483, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117988108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders YY, Cui Z, Le Saux CJ, Horowitz JC, Rangarajan S, Kurundkar A, Antony VB, Thannickal VJ. SMAD-independent down-regulation of caveolin-1 by TGF-β: effects on proliferation and survival of myofibroblasts. PLoS One 10: e0116995, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel PM, Massagué J. Cytostatic and apoptotic actions of TGF-beta in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 807–821, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nrc1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strand MJ, Sprunger D, Cosgrove GP, Fernandez-Perez ER, Frankel SK, Huie TJ, Olson AL, Solomon J, Brown KK, Swigris JJ. Pulmonary function and survival in idiopathic vs secondary usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest 146: 775–785, 2014. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanjore H, Blackwell TS, Lawson WE. Emerging evidence for endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L721–L729, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00410.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thannickal VJ, Aldweib KD, Fanburg BL. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates H2O2 production in lung fibroblasts stimulated by transforming growth factor beta1. J Biol Chem 273: 23611–23615, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thannickal VJ, Horowitz JC. Evolving concepts of apoptosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 3: 350–356, 2006. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-001TK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiery JP, Sleeman JP. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 131–142, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrm1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 349–363, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomassetti S, Gurioli C, Ryu JH, Decker PA, Ravaglia C, Tantalocco P, Buccioli M, Piciucchi S, Sverzellati N, Dubini A, Gavelli G, Chilosi M, Poletti V. The impact of lung cancer on survival of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 147: 157–164, 2015. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wahl SM, Swisher J, McCartney-Francis N, Chen W. TGF-beta: the perpetrator of immune suppression by regulatory T cells and suicidal T cells. J Leukoc Biol 76: 15–24, 2004. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wendt MK, Schiemann WP. Therapeutic targeting of the focal adhesion complex prevents oncogenic TGF-beta signaling and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res 11: R68, 2009. doi: 10.1186/bcr2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wheaton AK, Velikoff M, Agarwal M, Loo TT, Horowitz JC, Sisson TH, Kim KK. The vitronectin RGD motif regulates TGF-β-induced alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L1206–L1217, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00424.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willis BC, Borok Z. TGF-β-induced EMT: mechanisms and implications for fibrotic lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L525–L534, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00163.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willis BC, duBois RM, Borok Z. Epithelial origin of myofibroblasts during fibrosis in the lung. Proc Am Thorac Soc 3: 377–382, 2006. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-004TK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willis BC, Liebler JM, Luby-Phelps K, Nicholson AG, Crandall ED, du Bois RM, Borok Z. Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells by transforming growth factor-beta1: potential role in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 166: 1321–1332, 2005. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xaubet A, Marin-Arguedas A, Lario S, Ancochea J, Morell F, Ruiz-Manzano J, Rodriguez-Becerra E, Rodriguez-Arias JM, Inigo P, Sanz S, Campistol JM, Mullol J, Picado C. Transforming growth factor-beta1 gene polymorphisms are associated with disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 431–435, 2003. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1165OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu J, Lamouille S, Derynck R. TGF-beta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res 19: 156–172, 2009. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanagihara K, Tsumuraya M. Transforming growth factor beta 1 induces apoptotic cell death in cultured human gastric carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 52: 4042–4045, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanagisawa K, Osada H, Masuda A, Kondo M, Saito T, Yatabe Y, Takagi K, Takahashi T, Takahashi T. Induction of apoptosis by Smad3 and down-regulation of Smad3 expression in response to TGF-beta in human normal lung epithelial cells. Oncogene 17: 1743–1747, 1998. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, Duncan MB, Rieder F, Tanjore H, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem 282: 23337–23347, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zouq NK, Keeble JA, Lindsay J, Valentijn AJ, Zhang L, Mills D, Turner CE, Streuli CH, Gilmore AP. FAK engages multiple pathways to maintain survival of fibroblasts and epithelia: differential roles for paxillin and p130Cas. J Cell Sci 122: 357–367, 2009. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]