Abstract

Early-life wheezing-associated respiratory tract infection by rhinovirus (RV) is considered a risk factor for asthma development. We have shown that RV infection of 6-day-old BALB/c mice, but not mature mice, induces an asthmalike phenotype that is associated with an increase in the population of type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) and dependent on IL-13 and IL-25. We hypothesize that ILC2s are required and sufficient for development of the asthmalike phenotype in immature mice. Mice were infected with RV1B on day 6 of life and treated with vehicle or a chemical inhibitor of retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-α (RORα), SR3335 (15 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip for 7 days). We also infected Rorasg/sg mice without functional ILC2s. ILC2s were identified as negative for lineage markers and positive for cluster of differentiation 25 (CD25)/IL-2Rα and CD127/IL-7Rα. Effects of SR3335 on proliferation and function of cultured ILC2s were determined. Finally, sorted ILC2s were transferred into naïve mice, and lungs were harvested 14 days later for assessment of gene expression and histology. SR3335 decreased the number of RV-induced lung lineage-negative, CD25+, CD127+ ILC2s in immature mice. SR3335 also attenuated lung mRNA expression of IL-13, Muc5ac, and Gob5 as well as mucous metaplasia. We also found reduced expansion of ILC2s in RV-infected Rorasg/sg mice. SR3335 also blocked IL-25 and IL-33-induced ILC2 proliferation and IL-13 production ex vivo. Finally, adoptive transfer of ILC2s led to development of asthmalike phenotype in immature and adult mice. RORα-dependent ILC2s are required and sufficient for type 2 cytokine expression and mucous metaplasia in immature mice.

Keywords: asthma, type 2 innate lymphoid cells, newborn, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-α, rhinovirus

early-life wheezing-associated respiratory tract infections by rhinovirus (RV) are considered risk factors for asthma development (14, 17). We have shown that RV infection of 6-day-old BALB/c mice, but not mature mice, induces an asthmalike phenotype, including mucous metaplasia and airway hyperresponsiveness (34). Development of this phenotype is dependent on IL-13 and IL-25 (12). Furthermore, RV infection expanded the population of IL-13-producing type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s; 12). Although neutralization of IL-25 attenuated ILC2 expansion, IL-13, and mucous metaplasia, we did not prove the specific requirement of ILC2s in this study, nor did we examine the sufficiency of ILC2s to promote the asthma phenotype.

ILC2s are morphologically similar to lymphocytes but do not express T- or B-cell receptors or surface markers associated with other immune cell lineages. ILC2s express cluster of differentiation 90 (CD90)/Thy1, CD25 (IL-2Rα), and CD127 (IL-7Rα), and their development is dependent on the common γ-chain (γc or CD132), IL-7, Notch, DNA-binding protein inhibitor 2 (Id2), GATA3, and retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-α (RORα; 8, 15, 35). RORα was identified as the regulator of ILC2 differentiation and function using “staggerer” or Rorasg/sg mice, which carry a spontaneous deletion within the Rora gene (11). In these studies, expansion of the ILC2 population in response to IL-25, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection, or intranasal papain administration was severely impaired, resulting in failure of characteristic type 2 immune responses (9, 35). These results suggest a critical role for RORα in response to immune challenge in peripheral tissues.

We sought to examine the requirement of ILC2s for RV-induced IL-13 production and mucous metaplasia by selectively inhibiting RORα. However, although inhibition of RORα is an effective method of ablating ILC2s, Rorasg/sg mice do not breed well, and heterozygotes must be used, making it difficult to predict how many homozygotes will be available for experiments. RORafl/sgIl7rCre mice (28) with a tissue-specific defect of RORα have also been generated, but these mice were bred on C57BL/6 background. Therefore, in addition to using Rorasg/sg mice, we employed SR3335, a small-molecule RORα chemical inhibitor (16), to determine the requirement of ILC2s for RV-induced airway responses in immature mice. We also examined the sufficiency of ILC2s for mucous metaplasia in immature mice by adoptive transfer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of RV.

RV1B (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was grown in HeLa cells, concentrated and partially purified by ultrafiltration, as described (25). Similarly, concentrated and purified HeLa cell lysates were used for sham infection. Viral titer was measured by plaque assay (20). HeLa cell monolayers were infected with serially diluted RV and overlaid with a 0.6% agarose solution. Plaque growth was monitored by light microscopy and was confirmed by staining with crystal violet.

RV infection and treatment.

Experiments were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Six-day-old BALB/c mice or RORasg/sg mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were inoculated through the intranasal route under Forane anesthesia with RV1B (20 μl of 1 × 108 plaque-forming units (pfu)/ml viral stock) or an equal volume of sham HeLa cell lysate. On the same day as RV treatment, BALB/c mice were treated with SR3335 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI; 15 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip) or vehicle (10% ethanol in water), and the treatment was continued for a total of 7 days.

Lung histology and immunofluorescence.

Lungs were harvested 3 wk after RV treatment, in accordance with our previous report that RV induced mucus metaplasia at 2–3 wk postinfection (12). Lungs were perfused through the pulmonary artery with PBS containing 5 mM EDTA), fixed with 10% formaldehyde overnight, and paraffin embedded. Blocks were sectioned at 500-μm intervals at a thickness of 5 μm, and each section was deparaffinized, hydrated, and stained. To visualize mucus, sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Other lung sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated mouse anti-Muc5ac (clone 45M1; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Images were visualized using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope (Tokyo, Japan). The level of Muc5ac staining in the airway epithelium was quantified by National Institutes of Health ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD). One section from the middle region of the left lung was analyzed from each mouse. Muc5ac was represented as the percentage of Muc5ac-positive epithelium compared with the total basement membrane length.

Real-time quantitative PCR.

Lung and liver RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). and genomic DNA was digested using a DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD). RNA from cultured ILC2s was isolated using RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR using specific primers for mRNA. The level of gene expression for each sample was normalized to GAPDH.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Lungs from immature wild-type BALB/c or RORasg/sg mice were harvested 2 wk after sham or RV treatment, in accordance with our earlier report of ILC2 expansion 1–2 wk following infection (12). Lungs were perfused with PBS containing EDTA and minced and digested in collagenase IV. Cells were filtered and washed with red blood cell lysis buffer, and dead cells were stained with Pacific Blue Live/Dead fixable dead staining dye (Invitrogen). Nonspecific binding was blocked by 10% FBS with 1% LPS-free BSA and 5-µg rat anti-mouse CD16/32 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) added. To identify ILC2s, cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated antibodies for lineage markers [CD3ε, T-cell receptor-β (TCRβ), B220/CD45R, Ter-119, Gr-1/Ly-6G/Ly-6C, CD11b, CD11c, F4/80, and FcεRIα; all from BioLegend], anti-CD25-peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex (PerCP)-Cy5.5 (BioLegend), and anti-CD127-allophycocyanin (APC; eBioscience), as described (12). Cells were fixed, subjected to flow cytometry, and analyzed on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data were collected using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

ILC2 culture.

Six-day-old pups were infected with RV, and the lungs were harvested 7 days later for ILC2 isolation by flow cytometry. Lung cell suspensions were sorted for lineage-negative, CD25+, CD127+ ILC2s by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, as described above. ILC2s were plated at 5–6 × 103 cells/100 μl in 96-well plates. Sorted ILC2s were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and stimulated with a combination of IL-2, IL-7, IL-25, and IL-33 (10 ng/ml, each; R&D, Minneapolis, MN) according to a published protocol (22). After 3 days of stimulation, plates were centrifuged, and supernatants were tested for IL-13 with ELISA (eBioscience). Cell pellet RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and RNAs were concentrated using RNAstable (Sigma-Aldrich). cDNA was synthesized and subjected to quantitative PCR (qPCR) as described above.

ILC2 immunofluorescence.

ILC2s were plated on a 96-well plate at 5,000 cells/well. Cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and IL-7, with or without IL-25 and IL-33, and treated with SR3335 (5 μM; Cayman Chemical) or vehicle. For selected experiments, cells were cotreated with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; 10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Forty-eight hours later, the cytospin preparations were fixed in 50% methanol-50% acetone and stained with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (Life Technologies). For RORα immunofluorescence, cytospin-prepared slides were fixed in 50% methanol-50% acetone, permeabilized for 10 min using 0.03% Triton X-100, immunostained with RORα antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and visualized with Alexa Fluor 555-labeled secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Slides were mounted using ProLong Gold-Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

IL-13 ELISA.

IL-13 protein abundance in ILC2-conditioned medium was measured from conditioned media using an IL-13 ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit (eBioscience).

Adoptive transfer of ILC2s.

ILC2s were sorted from RV-infected mouse lungs, and 1–3 × 104 cells were intranasally transferred into each pup, as described (3). As controls, we also transferred lineage-positive cells, and ILC2s were treated with 5 μM SR3335 for an hour. Finally, in an additional experiment, we intranasally transferred 5 × 104 cells to mature (6–8-wk-old mice). Cells were stained with 10 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) before transfer. The lungs were harvested 14 days later, since we previously observed mucus metaplasia 2 wk after maximal ILC2 expansion (12). The lungs were processed for qPCR, histology, and immunofluorescence.

Data analysis.

All data are represented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was assessed by unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA as appropriate. Group differences were pinpointed by the Student-Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison test.

RESULTS

SR3335 treatment reduces RV-induced lung ILC2s in immature mice.

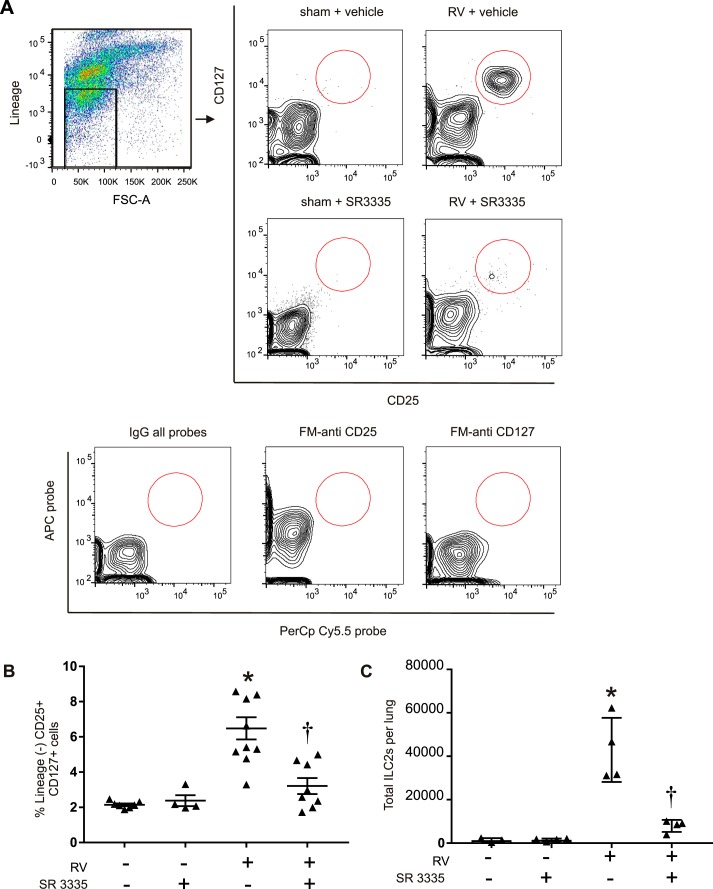

In our previous report, we found that RV infection of immature mice induced ILC2 expansion and type 2 immune responses leading to mucous metaplasia and airway hyperresponsiveness (12). To address the specific requirement of ILC2s in development of the asthma phenotype, we used SR3335, an inverse agonist of RORα (16). As shown previously, RV treatment increased lung ILC2s (Fig. 1). SR3335 treatment significantly attenuated the increase in ILC2s (Fig. 1, B and C), suggesting that RORα has a crucial role in ILC2 expansion.

Fig. 1.

Isolation of ILC2s from vehicle- or SR3335-treated lungs. Six-day-old mice were inoculated with sham or rhinovirus (RV), and live ILC2s were identified 14 days later. Lungs were digested with collagenase, stained with Pacific Blue-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester for dead cells, and subsequently stained with a lineage antibody cocktail as well as CD25 and CD127 antibodies. The gating procedure is shown in A. Cells were washed, fixed, and processed for flow cytometry. A: CD25+ and CD127+ population gated off of lineage-negative cells in sham + vehicle-, RV + vehicle-, and SR3335-treated group. FSC-A, forward scatter pulse area. B: ILC2s as a percentage of the lineage-negative cells. C: ILC2s as total number per lung (n = 4–11 per group, means ± SE, *P < 0.05 vs. sham + vehicle, †P < 0.05 vs. RV + vehicle, by ANOVA).

SR3335 treatment inhibits RV-induced mucus metaplasia in immature mice.

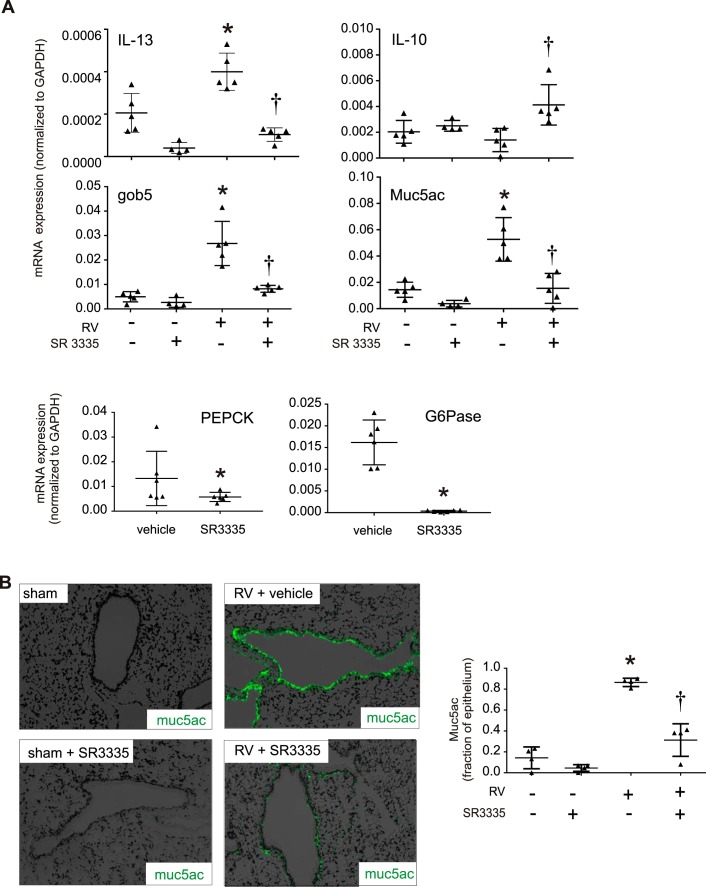

Since ILC2 expansion was associated with type 2 immune responses leading to mucous metaplasia and airway hyperresponsiveness in RV-infected immature mice (12), we examined whether the increase in lung ILC2s was required for RV-induced mucous metaplasia in immature mice. SR3335 treatment downregulated the type 2 cytokine IL-13 as well as the mRNA expression of two mucus-related genes, Muc5ac and Gob5 expression (Fig. 2A). We also found that expression of two RORα-regulated genes, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6 phosphatase (G6Pase), was significantly downregulated in response to SR3335 treatment (Fig. 2A), demonstrating that SR3335 blocks RORα activity. SR3335 reduced Muc5ac staining in the lungs of RV-infected mice, suggesting that RORα and ILC2s are required for mucous metaplasia (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effects of SR3335 on ILC2 activation and mucus metaplasia induced by RV in immature mice. Six-day-old mice were inoculated and treated with sham + vehicle, RV + vehicle, sham + SR3335, or RV + SR3335. Lungs were harvested 21 days later and processed for RNA and histology. A: graphs showing real-time analysis of indicated genes in sham + vehicle-, RV + vehicle-, and RV + SR3335-treated mice (n = 5 per group, means ± SE, *P < 0.05 vs. sham + vehicle, †P < 0.05 vs. RV + vehicle, by ANOVA). B: Muc5ac staining in sham + vehicle-, RV + vehicle-, sham + SR3335-, and RV + SR3335-treated mouse lungs (data indicate percentages of Muc5ac staining from 4 animals per group, means ± SE, *P < 0.05 vs. sham + vehicle, †P < 0.05 vs. RV + vehicle, by ANOVA).

SR3335 inhibits ILC2 activation and proliferation.

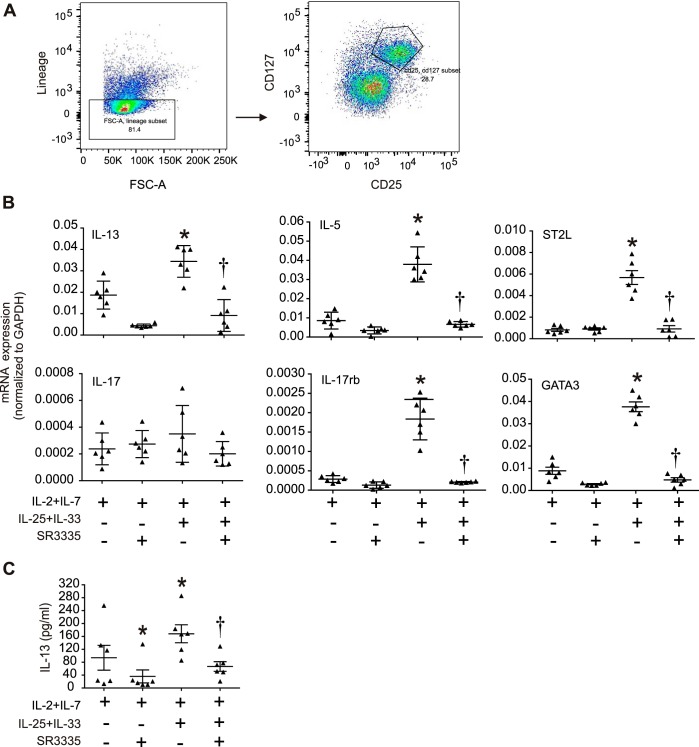

We examined the requirement of RORα for IL-25 and IL-33-induced ILC2 responses ex vivo. We sorted ILC2s from RV-infected immature mice (Fig. 3A) and cultured them in 96-well plates in the presence of IL-2 and IL-7. Treatment of ILC2s with IL-25 and IL-33 in vitro induced mRNA expression of the type 2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13, as well as expression of the IL-33 receptor ST2L, the IL-25 receptor IL-17RB, and the ILC2 transcription factor GATA3. SR3335 treatment attenuated expression of these genes (Fig. 3B). We also measured IL-13 protein levels in the ILC2-conditioned media and found that IL-25 and IL-33 together induced IL-13 protein levels and that this effect was blocked by SR3335 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of SR3335 on ILC2 activation in vitro. Six-day-old mice were inoculated with rhinovirus (RV), and lungs were harvested 1 wk later. Lungs were digested with collagenase, stained with DAPI for dead cells and subsequently stained with a lineage antibody cocktail as well as CD25 and CD127 antibodies. The lineage-negative cells were isolated and sorted for CD25 and CD127 double-positive ILC2s. ILC2s were plated on a 96-well plate at 5,000 cells/well. The cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and IL-7 with or without IL-25 + IL-33 and were treated with SR3335 or vehicle. RNA was isolated 48 h later, and expression of indicated genes was determined. For IL-13 assay, media was collected and assayed for IL-13 by ELISA. A: flow analysis for ILC2 sorting. B: graphs showing expression of ILC2 markers, i.e., IL-13, IL-5, ST2L, IL-17, IL-17RB, and GATA3, with the indicated treatments. C: graph showing IL-13 production with the indicated treatments of ILC2s. (For B and C, n = 6 per group, means ± SE, *P < 0.05 vs. IL-2 + IL-7, †P < 0.05 vs. IL-2 + IL-7 + IL-25 + IL-33, by ANOVA.)

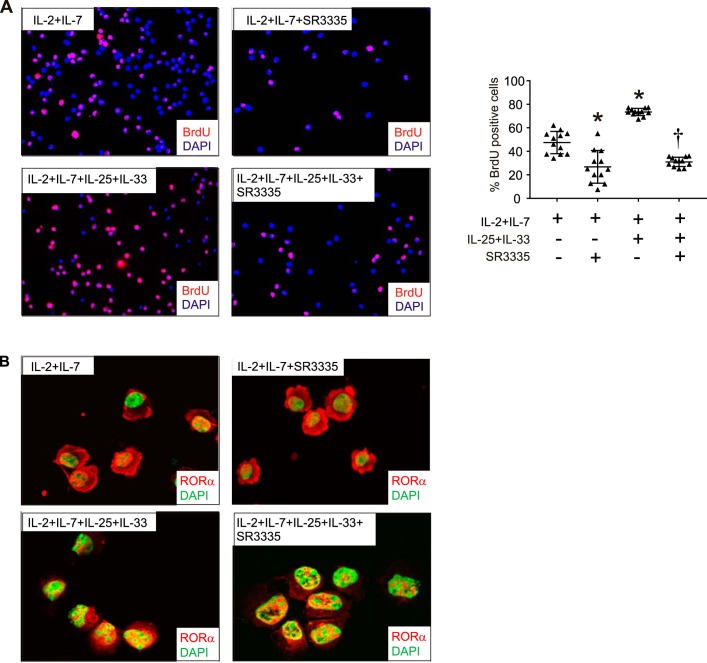

We also determined whether SR3335 regulates ILC2 expansion in vitro. SR3335 significantly blocked IL-25 and IL-33-induced ILC2 proliferation, as evidenced by BrdU uptake (Fig. 4A). We also determined whether IL-25 and IL-33 treatment of ILC2s affects subcellular localization of RORα. In cells treated with IL-2 and IL-7 alone, RORα was mostly cytosolic (Fig. 4B). Treatment with IL-25 and IL-33 increased nuclear localization of RORα, with more staining in the nucleus and minimal cytosolic staining. Finally, SR3335 treatment had no effect on nuclear localization of RORα.

Fig. 4.

Effects of SR3335 on ILC2 proliferation and RORα localization in vitro. Six-day-old mice were inoculated with RV, and lungs were harvested 1 wk later. Lungs were digested with collagenase and successively stained with DAPI for dead cells, lineage antibody cocktail, and antibodies against CD25 and CD127. The lineage-negative cells were isolated and sorted for CD25 and CD127 double-positive ILC2s. ILC2s were plated on a 96-well plate at 5,000 cells/well. The cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and IL-7 with or without IL-25 + IL-33 and were treated with SR3335 or vehicle. Selected cells were cotreated with BrdU. After treatment, cytospin-prepared slides were fixed for immunofluorescence detection of BrdU incorporation. Selected cytospin-prepared cells were fixed for immunofluorescence detection of RORα. A: BrdU staining and quantification after indicated treatments of ILC2s (n = 12 wells per group; cells were pooled from 6 different mice in 2 separate experiments, means ± SE, *P < 0.05 vs. IL-2 + IL-7, †P < 0.05 vs. IL-2 + IL-7 + IL-25 + IL-33, by ANOVA). B: images showing nuclear localization of RORα following the indicated treatments.

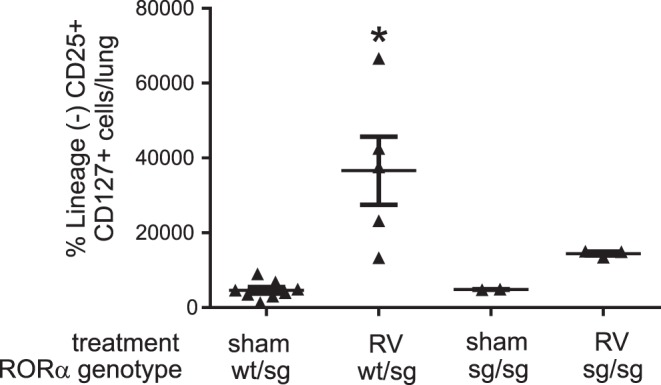

RORasg/sg mice show reduced lung ILC2s in response to RV.

Rorasg/sg mice carry a spontaneous deletion within the Rora gene that prevents translation of the ligand-binding homology domain and gives rise to a phenotype similar to RORα deficiency (11). Previous studies have shown that Rorasg/sg mice fail to increase ILC2 cell populations in response to IL-25 (35) or protease allergen, thus confirming the essential role of ILC2s in allergic lung inflammation (9). In view of these findings, we determined the effect of RV infection in immature RORasg/sg mice. We indeed found that whereas RV treatment increased lung ILC2s in RORasg/+ mice, there was no increase in RV-infected homozygous RORasg/sg mice (Fig. 5). We did not observe any differences in ILC2 numbers between sham-treated RORasg/sg and RORasg/+ mice.

Fig. 5.

RORasg/sg mice show a lower ILC2 response to RV. A litter from a heterozygotic breeding was treated with sham or RV on day 6 of life and harvested for ILC2s on day 12. The graph shows ILC2 number (n = 2–6, *P < 0.05 vs. sham); wt, wild type.

Adoptive transfer of ILC2s induces mucus metaplasia in immature mice.

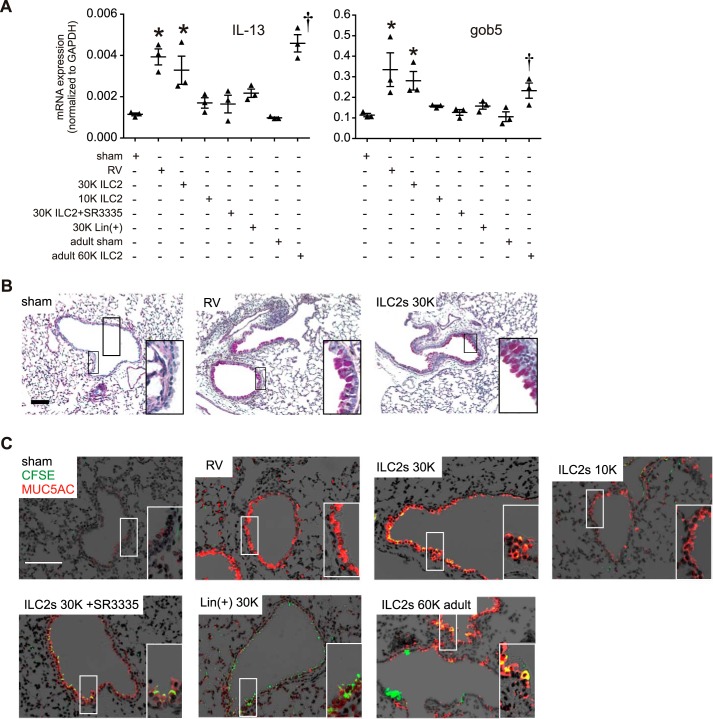

We showed that the RORα inhibitor SR3335 blocked the increase in ILC2 cell number and development of an asthmalike phenotype in RV-infected immature mice. To test the sufficiency of ILC2s for mucous metaplasia in immature mice, lung ILC2s were obtained from RV-infected mice and transferred intranasally to naïve 6-day-old animals and mature 6–8-wk-old mice. As controls, we also treated selected mice with SR3335-treated ILC2s and lineage-positive cells. Cells were stained with CFSE before transfer. Two weeks later, lungs were harvested for qPCR or sectioned and stained for PAS and Muc5ac immunofluorescence. Adoptive transfer of ILC2s from RV-infected immature mice to 6-day-old mice dose-dependently induced lung IL-13, Gob5, and Muc5ac mRNA expression (Fig. 6A), as well as mucous metaplasia (Fig. 6, B and C). Airways stained positive for CFSE indicating the presence of ILC2s or ILC2 debris. In contrast, transfer of SR3335-treated ILC2s or lineage-positive cells did not induce the mRNA expression of mucus-related genes. Finally, as expected, transfer of IL-13-producing ILC2s from immature animals was sufficient to induce Muc5ac expression in mature animals.

Fig. 6.

Adoptive transfer of ILC2s induces mucus metaplasia in immature mice. Six-day-old mice were inoculated with RV, and lungs were harvested 1 wk later. Lungs were digested with collagenase and successively stained with DAPI for dead cells, lineage antibody cocktail, and CD25 and CD127 antibodies. The lineage-negative cells were isolated and sorted for CD25 and CD127 double-positive ILC2s. Lineage-positive cells were also sorted. The cells were adoptively transferred intranasally into 6-day-old or adult mice according to the indicated groups. Other pups were treated with sham or RV as controls. For assessment of mucus metaplasia, the lungs were harvested 2 wk later and were processed for RNA, histology, and immunofluorescence. A: graphs showing real-time analysis of IL-13, Gob5, and Muc5ac mRNA in sham, ILC2, and RV group (n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. immature sham, †P < 0.05 vs. adult sham). PAS (B) and Muc5ac (C) staining in sham-, RV-, and ILC2-treated mice. For fluorescence microscopy, Muc5ac staining is shown in red, and CFSE is shown in green. Lin(+), lineage positive; K, 1,000.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a novel contribution of ILC2s to mucous metaplasia in RV-infected immature mice. We previously showed that RV infection of 6-day-old BALB/c mice, but not mature mice, induces an asthmalike phenotype that is associated with ILC2 expansion and dependent on IL-13 and IL-25 (12). In the present study, we determined whether inhibition of ILC2 expansion prevents the RV-induced asthmalike phenotype in immature mice. We found that SR3335, an inhibitor of RORα, prevented the RV-induced increase in lung ILC2s. A similar inhibition of ILC2s was found in RV-infected RORasg/sg. The loss of ILC2s was accompanied by a reduction in the type 2 cytokine IL-13 as well as the mRNA expression of two mucus-related genes, Muc5ac and Gob5 expression. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of lung ILC2s from RV-infected mice was sufficient to induce mucous metaplasia. Together, these results are consistent with the notion that ILC2s may play a role in the development of asthma following early-life viral infection in human infants.

RORα was identified as a regulator of ILC2 differentiation and function using “staggerer” or Rorasg/sg mice, which carry a spontaneous deletion within the Rora gene (11). We therefore employed an inverse agonist of RORα, SR3335, to block ILC2 effects. We found that administration of SR3335 inhibited mRNA expression of PEPCK and G6Pase, known target genes of RORα, demonstrating that SR3335 blocked RORα activity. These data extend previous studies by Kumar et al. (16) showing that SR3335 blocked expression of a luciferase reporter gene driven by a G6Pase promoter in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells. These authors also showed that SR3335 displayed no activity for any other receptors in a selectivity panel for human nuclear receptors such as RORβ, RORγ, and fragile X mental retardation autosomal homolog 1 (FXR1; 16). We examined the effects of SR3335 on mRNA expression of IL-17 and IL-22, known targets of RORγ (data not shown). We did not find an inhibitory effect, although the expression of these genes was low in our system. Taken together, these data suggest that SR3335 specifically inhibited RORα in our study. As far as we are aware, our study is the first to explore the potential efficacy of SR3335 in the treatment of airway disease. SR3335 has also been shown to suppress G6Pase and plasma glucose levels in a diet-induced obesity mouse model, suggesting that RORα inverse agonists may hold utility for suppression of elevated hepatic gluconeogenesis in type 2 diabetics.

The epithelial-derived “innate cytokines” IL-25 and IL-33 have each been reported to induce type 2 immune responses as well as to induce and activate ILC2s both in humans and mice (13, 21, 24, 31). Overexpression of IL-25, a member of the IL-17 cytokine family that binds to IL-17RB, increases IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, airway responsiveness, and IgE (5, 30, 32), whereas deficiency reduces type 2 cytokine production (7, 29). Furthermore, we reported that epithelial IL-25 is increased following neonatal but not adult RV infection and mediates ILC2 expansion, mucous metaplasia, and airway hyperresponsiveness in RV-infected neonatal mice (12). IL-33, a member of the IL-1 family that signals through the IL-1 receptor homolog suppression of tumorigenicity 2 transmembrane isoform (ST2L), is constitutively expressed as a nuclear precursor in alveolar epithelial cells (18) and released from producing cells upon cellular damage (19). IL-33 is also expressed in airway epithelial and inflammatory cells after allergen challenge (23) and submucosal inflammatory cells of children with steroid-resistant asthma (33). IL-33 is required for ovalbumin- and papain-induced airway inflammation (18, 27).

It has been suggested that IL-33 is more potent than IL-25 in inducing IL-13 producing ILC2s and airway hyperresponsiveness (1). We therefore examined the responses of cultured ILC2s to IL-25 and IL-33 and the requirement of RORα for ILC2 gene expression and proliferation. Both IL-25 and IL-33 were sufficient for ILC2 gene expression and proliferation; however, the combination of IL-25 and IL-33 caused greater responses. SR3335 suppressed IL-25 and IL-33-induced production of IL-13 and mRNA expression of IL-5, ST2, IL-17RB, and GATA3. The precise mechanism by which RORα regulates expression of these genes remains to be elucidated. SR3335 treatment did not reverse IL-25 and IL-33-induced nuclear translocation of RORα. These data are consistent with the notion that the RORα DNA-binding domain, rather than the ligand-binding domain, carries the nuclear localization signal (2). Instead, it is possible that engagement of the RORα ligand-binding domain by SR3335 limits the receptor's ability to activate transcription by inhibiting coactivator protein recruitment.

Rorasg/sg mice also showed a reduction in RV-induced ILC2 expansion. Our finding of ILC2 suppression in mutant homozygotes but not heterozygotes suggests that half-maximal RORα function is sufficient for ILC2 expansion. These data are in accordance with a previous study demonstrating nearly undetectable ILC2s in the lungs and intestines of Rorasg/sg mice but normal ILC2 number in heterozygous Rorasg/+ mice (9).

We also found that adoptive transfer of ILC2s isolated from RV-infected immature mice to naïve 6-day-old mice mimicked the response to RV infection, as evidenced by induction of IL-13 and mucus metaplasia, identifying ILC2s as a potent proasthmatic stimulus in immature mice. Transfer of SR335-treated ILC2s or lineage-positive cells failed to induce the asthmalike phenotype. In addition, transfer of ILC2s to mature mice also induced mucous metaplasia, consistent with the notion that the absence of RV-induced mucous metaplasia we observed in adult mice (12) was due to the lack of ILC2 expansion. Few studies have examined the effects of ILC2 transfer to the lungs and other tissues. ILC2- and CD4 T cell-deficient IL7ra−/− mice reconstituted with ILC2s alone showed a modest increase in eosinophil numbers and IL-13 levels in response to intranasal challenge with ovalbumin and bromelain, a cysteine protease (4). Cotransfer of CD4 T cells was required for a robust antigen-specific type 2 cytokine-driven inflammatory response, consistent with recent data indicating that ILC2s influence the onset of the adaptive T helper 2 (Th2) response through a variety of mechanisms, including elaboration of type 2 cytokines and OX40 ligand as well as modification of dendritic cell function at mucosal surfaces (4, 6, 10). In another study, adoptive transfer of ILC2s restored food allergen sensitization in Il4raF709 IL-33 receptor-deficient (Il1rl1−/−) mice (26). Finally, it was recently reported that adoptive transfer of ILC2s to ILC2-depleted mice restored ozone-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness (36). Our data confirm that ILC2s may play a causal role in the development of an asthmalike phenotype in response to a nonallergic challenge.

It should be noted that we concluded that SR3335 reduces lung ILC2s in vivo by measuring the number of lineage-negative, CD25+, CD127+ cells. We did not confirm the loss of ILC2s with other markers such as ST2. However, since we and others (35) showed that RORα has extensive inhibitory effects on ILC2 gene expression, we conclude that the effect of SR3335 on lung ILC2 number was not simply due to specific inhibition of the CD25 and CD127 surface markers that we used to detect ILC2s, but a real reduction in the number of functional ILC2s.

In conclusion, we have identified a novel role for ILC2s in the development of mucous metaplasia in immature mice. These data identify a potential mechanism by which early-life viral infections, including those with RV, in combination with other factors such as genetic background, allergen exposure, and microbiome, could promote childhood asthma development.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant 120526.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.R. and M.B.H. conceived and designed research; C.R., T.C., M.H., J.L., J.L.H., Q.W., J.K.B., and M.B.H. performed experiments; C.R., T.C., J.K.B., and M.B.H. analyzed data; C.R., T.C., J.K.B., and M.B.H. interpreted results of experiments; C.R., J.K.B., and M.B.H. prepared figures; C.R. drafted manuscript; J.K.B. and M.B.H. edited and revised manuscript; C.R., J.K.B., and M.B.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barlow JL, Peel S, Fox J, Panova V, Hardman CS, Camelo A, Bucks C, Wu X, Kane CM, Neill DR, Flynn RJ, Sayers I, Hall IP, McKenzie ANJ. IL-33 is more potent than IL-25 in provoking IL-13-producing nuocytes (type 2 innate lymphoid cells) and airway contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132: 933–941, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chopin-Delannoy S, Thénot S, Delaunay F, Buisine E, Begue A, Duterque-Coquillaud M, Laudet V. A specific and unusual nuclear localization signal in the DNA binding domain of the Rev-erb orphan receptors. J Mol Endocrinol 30: 197–211, 2003. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0300197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cormier SA, Shrestha B, Saravia J, Lee GI, Shen L, DeVincenzo JP, Kim YI, You D. Limited type I interferons and plasmacytoid dendritic cells during neonatal respiratory syncytial virus infection permit immunopathogenesis upon reinfection. J Virol 88: 9350–9360, 2014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00818-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drake LY, Iijima K, Kita H. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4+ T cells cooperate to mediate type 2 immune response in mice. Allergy 69: 1300–1307, 2014. doi: 10.1111/all.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fort MM, Cheung J, Yen D, Li J, Zurawski SM, Lo S, Menon S, Clifford T, Hunte B, Lesley R, Muchamuel T, Hurst SD, Zurawski G, Leach MW, Gorman DM, Rennick DM. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity 15: 985–995, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold MJ, Antignano F, Halim TYF, Hirota JA, Blanchet M-R, Zaph C, Takei F, McNagny KM. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells facilitate sensitization to local, but not systemic, TH2-inducing allergen exposures. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133: 1142–1148, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory LG, Jones CP, Walker SA, Sawant D, Gowers KHC, Campbell GA, McKenzie ANJ, Lloyd CM. IL-25 drives remodelling in allergic airways disease induced by house dust mite. Thorax 68: 82–90, 2013. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity 36: 451–463, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halim TY, MacLaren A, Romanish MT, Gold MJ, McNagny KM, Takei F. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity 37: 463–474, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halim TY, Steer CA, Mathä L, Gold MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez I, McNagny KM, McKenzie AN, Takei F. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity 40: 425–435, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton BA, Frankel WN, Kerrebrock AW, Hawkins TL, FitzHugh W, Kusumi K, Russell LB, Mueller KL, van Berkel V, Birren BW, Kruglyak L, Lander ES. Disruption of the nuclear hormone receptor RORalpha in staggerer mice. Nature 379: 736–739, 1996. doi: 10.1038/379736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong JY, Bentley JK, Chung Y, Lei J, Steenrod JM, Chen Q, Sajjan US, Hershenson MB. Neonatal rhinovirus induces mucous metaplasia and airways hyperresponsiveness through IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 134: 429–439, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Guo L, Qiu J, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Siebenlist U, Williamson PR, Urban JF Jr, Paul WE. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential 'inflammatory' type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol 16: 161–169, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ni.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, Roberg KA, Anderson EL, Pappas TE, Printz MC, Lee W-M, Shult PA, Reisdorf E, Carlson-Dakes KT, Salazar LP, DaSilva DF, Tisler CJ, Gern JE, Lemanske RF Jr. Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178: 667–672, 2008. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein Wolterink RGJ, Serafini N, van Nimwegen M, Vosshenrich CAJ, de Bruijn MJW, Fonseca Pereira D, Veiga Fernandes H, Hendriks RW, Di Santo JP. Essential, dose-dependent role for the transcription factor Gata3 in the development of IL-5+ and IL-13+ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 10240–10245, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217158110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar N, Kojetin DJ, Solt LA, Kumar KG, Nuhant P, Duckett DR, Cameron MD, Butler AA, Roush WR, Griffin PR, Burris TP. Identification of SR3335 (ML-176): a synthetic RORα selective inverse agonist. ACS Chem Biol 6: 218–222, 2011. doi: 10.1021/cb1002762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemanske RF Jr, Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, Li Z, Shult PA, Kirk CJ, Reisdorf E, Roberg KA, Anderson EL, Carlson-Dakes KT, Adler KJ, Gilbertson-White S, Pappas TE, Dasilva DF, Tisler CJ, Gern JE. Rhinovirus illnesses during infancy predict subsequent childhood wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol 116: 571–577, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louten J, Rankin AL, Li Y, Murphy EE, Beaumont M, Moon C, Bourne P, McClanahan TK, Pflanz S, de Waal Malefyt R. Endogenous IL-33 enhances Th2 cytokine production and T-cell responses during allergic airway inflammation. Int Immunol 23: 307–315, 2011. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lüthi AU, Cullen SP, McNeela EA, Duriez PJ, Afonina IS, Sheridan C, Brumatti G, Taylor RC, Kersse K, Vandenabeele P, Lavelle EC, Martin SJ. Suppression of interleukin-33 bioactivity through proteolysis by apoptotic caspases. Immunity 31: 84–98, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin S, Casasnovas JM, Staunton DE, Springer TA. Efficient neutralization and disruption of rhinovirus by chimeric ICAM-1/immunoglobulin molecules. J Virol 67: 3561–3568, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mjösberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, Peters CP, van Drunen CM, Piet B, Fokkens WJ, Cupedo T, Spits H. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol 12: 1055–1062, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moro K, Ealey KN, Kabata H, Koyasu S. Isolation and analysis of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in mice. Nat Protoc 10: 792–806, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nabe T, Wakamori H, Yano C, Nishiguchi A, Yuasa R, Kido H, Tomiyama Y, Tomoda A, Kida H, Takiguchi A, Matsuda M, Ishihara K, Akiba S, Ohya S, Fukui H, Mizutani N, Yoshino S. Production of interleukin (IL)-33 in the lungs during multiple antigen challenge-induced airway inflammation in mice, and its modulation by a glucocorticoid. Eur J Pharmacol 757: 34–41, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TKA, Bucks C, Kane CM, Fallon PG, Pannell R, Jolin HE, McKenzie ANJ. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature 464: 1367–1370, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newcomb DC, Sajjan U, Nanua S, Jia Y, Goldsmith AM, Bentley JK, Hershenson MB. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is required for rhinovirus-induced airway epithelial cell interleukin-8 expression. J Biol Chem 280: 36952–36961, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noval Rivas M, Burton OT, Oettgen HC, Chatila T. IL-4 production by group 2 innate lymphoid cells promotes food allergy by blocking regulatory T-cell function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 138: 801–811.e9, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oboki K, Ohno T, Kajiwara N, Arae K, Morita H, Ishii A, Nambu A, Abe T, Kiyonari H, Matsumoto K, Sudo K, Okumura K, Saito H, Nakae S. IL-33 is a crucial amplifier of innate rather than acquired immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18581–18586, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003059107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliphant CJ, Hwang YY, Walker JA, Salimi M, Wong SH, Brewer JM, Englezakis A, Barlow JL, Hams E, Scanlon ST, Ogg GS, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity 41: 283–295, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owyang AM, Zaph C, Wilson EH, Guild KJ, McClanahan T, Miller HR, Cua DJ, Goldschmidt M, Hunter CA, Kastelein RA, Artis D. Interleukin 25 regulates type 2 cytokine-dependent immunity and limits chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med 203: 843–849, 2006. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan G, French D, Mao W, Maruoka M, Risser P, Lee J, Foster J, Aggarwal S, Nicholes K, Guillet S, Schow P, Gurney AL. Forced expression of murine IL-17E induces growth retardation, jaundice, a Th2-biased response, and multiorgan inflammation in mice. J Immunol 167: 6559–6567, 2001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price AE, Liang H-E, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, Locksley RM. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 11489–11494, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rickel EA, Siegel LA, Yoon B-RP, Rottman JB, Kugler DG, Swart DA, Anders PM, Tocker JE, Comeau MR, Budelsky AL. Identification of functional roles for both IL-17RB and IL-17RA in mediating IL-25-induced activities. J Immunol 181: 4299–4310, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saglani S, Lui S, Ullmann N, Campbell GA, Sherburn RT, Mathie SA, Denney L, Bossley CJ, Oates T, Walker SA, Bush A, Lloyd CM. IL-33 promotes airway remodeling in pediatric patients with severe steroid-resistant asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132: 676–685, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider D, Hong JY, Popova AP, Bowman ER, Linn MJ, McLean AM, Zhao Y, Sonstein J, Bentley JK, Weinberg JB, Lukacs NW, Curtis JL, Sajjan US, Hershenson MB. Neonatal rhinovirus infection induces mucous metaplasia and airways hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol 188: 2894–2904, 2012. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong SH, Walker JA, Jolin HE, Drynan LF, Hams E, Camelo A, Barlow JL, Neill DR, Panova V, Koch U, Radtke F, Hardman CS, Hwang YY, Fallon PG, McKenzie ANJ. Transcription factor RORα is critical for nuocyte development. Nat Immunol 13: 229–236, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Q, Ge MQ, Kokalari B, Redai IG, Wang X, Kemeny DM, Bhandoola A, Haczku A. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells mediate ozone-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol 137: 571–578, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]