Abstract

Ectopic fat located in the kidney has emerged as a novel cause of obesity-related chronic kidney disease (CKD). In this study, we aimed to investigate whether inflammatory stress promotes ectopic lipid deposition in the kidney and causes renal injury in obese mice and whether the pathological process is mediated by the fatty acid translocase, CD36. High-fat diet (HFD) feeding alone resulted in obesity, hyperlipidemia, and slight renal lipid accumulation in mice, which nevertheless had normal kidney function. HFD-fed mice with chronic inflammation had severe renal steatosis and obvious glomerular and tubular damage, which was accompanied by increased CD36 expression. Interestingly, CD36 deficiency in HFD-fed mice eliminated renal lipid accumulation and pathological changes induced by chronic inflammation. In both human mesangial cells (HMCs) and human kidney 2 (HK2) cells, inflammatory stress increased the efficiency of CD36 protein incorporation into membrane lipid rafts, promoting FFA uptake and intracellular lipid accumulation. Silencing of CD36 in vitro markedly attenuated FFA uptake, lipid accumulation, and cellular stress induced by inflammatory stress. We conclude that inflammatory stress aggravates renal injury by activation of the CD36 pathway, suggesting that this mechanism may operate in obese individuals with chronic inflammation, making them prone to CKD.

Keywords: fatty acid/transport, ectopic lipid deposition, cytokines, receptors, lipids, renal disease, cluster of differentiation 36

The global increase in chronic kidney disease (CKD) parallels the obesity epidemic, and obese people have an increased risk of progression of CKD (1). Numerous epidemiologic data suggest that a higher body mass index is a strong independent risk factor for CKD, even after adjusting for traditional risk factors, including blood pressure, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (2–4). However, it is confusing that many people with congenital and acquired obesity do not suffer renal injury and failure (5–7). A large renal biopsy-based clinicopathologic study indicated that a small subset of morbidly obese individuals develops obesity-related glomerulopathy (ORG) (8). A study of 257 obese patients in the US revealed only four (1.6%) had dipstick proteinuria, a value much lower than the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension (15% and 23%, respectively) in the same population. These epidemiologic studies implied that CKD does not always occur in obese individuals, which leads to the question: why is CKD not developed by all obese patients?

Obesity has been associated with a renal complication that is known as ORG, with predominant histological characteristics of glomerulomegaly and secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (8). The mechanisms by which obesity progresses to ORG are not completely understood, but multiple studies have consistently suggested the critical role of glomerular hyperfiltration and insulin resistance (9–12). Gene expression profiles in the glomeruli obtained from ORG patients showed a high expression pattern of genes involved in lipid metabolism [LDL receptor (LDLr), sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1] and inflammation (TNFα, interleukin (IL)-6, and interferon-γ), suggesting that local lipid dysmetabolism and inflammatory processes are also required for the induction and progression of obesity-related CKD (13, 14).

Extensive studies suggest that chronic inflammation is a major contributor to progressive renal injury, leading to the development of CKD (15). Earlier studies from our laboratory have disclosed the role of inflammatory stress in lipid metabolism disorder. We found that chronic inflammation leads to lipid accumulation in the liver by impairing the balance of lipid influx and efflux (16–18). Additionally, chronic inflammation increased lipogenesis in nonadipose tissues and stimulated lipolysis in white adipose tissue, resulting in ectopic lipid deposition in the liver and muscle of mice (19). However, whether the kidney is similarly susceptible to ectopic lipid accumulation as liver or muscle, the contribution of inflammation to ectopic lipid deposition in the kidney, and the progression of obesity-related CKD are largely unknown.

Excess accumulation of nonesterified FFA and triglyceride (TG) in the kidney induce cellular lipotoxicity, potentially contributing to CKD development (20). It is well-known that cells can take up FFA by passive diffusion and also by receptor-mediated mechanisms involving several fatty acid transporters, of which the fatty acid translocase, CD36, is the best characterized (21). CD36 is an integral transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in various tissues, where it is involved in high-affinity uptake of long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) (22). Increased CD36 expression was observed in the kidneys of patients with CKD (23, 24), suggesting that CD36 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of renal diseases (24–26).

In this study, we aimed to determine whether inflammation induces ectopic lipid deposition in the kidney and confers susceptibility to the development of renal disease in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed obese mice and whether CD36-regulated fatty acid uptake is involved in this process. In the casein injection-induced model of chronic inflammation, we found that casein injection in HFD-fed mice led to renal alterations and accompanying systemic abnormalities compatible to human obesity-related CKD, including albuminuria, renal lipid accumulation, and glomerular lesions. These abnormalities were prevented by the loss of CD36 in mice, suggesting that the CD36 pathway contributes to the development of obesity-related CKD under chronic inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model

Animal care and experimental procedures were performed with approval from the animal care committees of Chongqing Medical University. CD36 knockout (CD36−/−) mice created on a C57BL/6J background were kindly provided by Dr. Maria Febbraio (Lerner Research Institute). Six-week-old male C57BL/6J (WT) mice and CD36−/− mice were used in this study. In one experiment, WT mice were randomly assigned to receive a normal chow diet (NCD) (D12102C; Research Diets) or NCD plus subcutaneous casein injection of 0.5 ml 10% casein every other day or a HFD (60% kcal in fat, D12492; Research Diets) or HFD plus casein injection (HFD+casein) (n = 5 mice per group). In another experiment, WT and CD36−/− mice were fed a HFD plus casein injection (n = 5 mice per group). Mice were euthanized after 10 weeks, and blood and kidney samples were collected for further assessments.

Cell culture

Human mesangial cells (HMCs) were cultured in RPMI-1640 growth medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% insulin-transferrin-sodium selenite, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Human kidney 2 (HK2) cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 growth medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Experimental medium was prepared with serum-free RPMI-1640 growth medium containing 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA (Sigma, Poole, Dorset, UK), and the cells were subjected to palmitic acid (PA) (0.04 mmol/l) loading in the absence or presence of TNFα (25 ng/ml) or IL-6 (20 ng/ml) for 24 h. PA was obtained from Sigma, and TNFα and IL-6 were purchased from Peprotech (Peprotech Asia, Rehovot, Israel).

Serum analysis

The serum levels of serum amyloid A (SAA) protein and TNFα were measured using commercial kits (United States Biological, Swampscott, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum concentrations of FFA, TG, creatinine, albumin, and blood urea nitrogen (BuN) were determined using an AU2700 automatic biochemical analyzer (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Lipid measurement

Quantitative measurement of FFA and TG levels in cells and kidneys were performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Cusabio Biotech Co. Ltd, Wuhan, China).

Renal histology and Oil Red O staining

Renal samples were collected and fixed in 10% formalin. The samples were then embedded in paraffin, sliced to 8 μm in thickness, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and periodic acid-silver methenamine (PASM) to evaluate the renal structural changes. For lipid analysis, frozen sections of kidneys were fixed and stained with Oil Red O for 15–30 min, and samples, after being washed, were then stained with hematoxylin for another 2 min. All images were captured using a Zeiss microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies were performed on sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded kidney tissues. Endogenous peroxidases were inactivated using 3% H2O2, followed by blocking with goat serum. Sections were incubated overnight (4°C) with anti-collagen 4 (1:200; Santa Cruz, CA), anti-GRP78 (1:200; Bioss, Beijing, China), or anti-IRE1 (1:200; Bioss). Then, the sections were washed and incubated for 45 min with secondary antibody. Histochemical reactions were performed using a diaminobenzidine kit, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. All images were captured using a Zeiss microscope (Zeiss).

Immunofluorescent staining

HK2 cells and HMCs cultured on coverslips were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 and blocked with 1% BSA for 30 min. Incubation with primary antibody against CD36 (1:2,000; Novus) was performed overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with secondary antibody (1:200; Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotech, Beijing, China). The cells were washed and stained with DAPI (1:50, Beyotime, Beijing, China) for 1 min. Fluorescence images were obtained using a florescence microscope (Zeiss).

Measurement of FFA uptake

To assess the uptake and accumulation of FFA, HMCs and HK2 cells were washed with PBS and loaded with fluorescent probe, BODIPY FL C16 (D3821; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). The uptake and accumulation of FFA in HMCs and HK2 cells were examined simultaneously in vitro using a confocal microscope until a plateau was obtained, and the fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 505 nm and an emission wavelength of 510 nm.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from white adipose tissue by RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Dalian, China). Then, cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR were performed with commercial kits (Takara) using the Bio-Rad CFX Connect TM real-time system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative expression compared with that of β-actin was calculated using the comparative cycle threshold method.

Western blot

The total proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer. Sample proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE in a Bio-Rad Mini protean apparatus (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membranes were then blocked and incubated with primary antibodies against CD36 (1:200; Novus) followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (Santa Cruz). Finally, detection procedures were performed using an ECL Advance Western blotting detection kit (Bio-Rad).

Isolation and analysis of detergent-resistant membranes

Plasma membrane lipid rafts, identified as detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs), were prepared by flotation on sucrose density gradients by ultracentrifugation of Triton X-100 lysates, as previously described (27). Briefly, cells were lysed for 20 min on ice in TNE buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors. Postnuclear supernatants were added with an equal volume of 80% sucrose, overlaid with 30% sucrose, topped by 5% sucrose, and then run on discontinuous sucrose gradients (40–5%) at 2,260 g for 15 h at 4°C. Fractions divided into 12 parts were collected from the top of the gradient, and equal protein amounts from each fraction were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s t-test when only two value sets were compared and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test when the data involved three or more groups. P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Chronic inflammation induced by casein aggravates renal injury in HFD-fed mice

Subcutaneous casein injection in C57BL/6J mice was previously reported to induce chronic inflammation in vivo (28, 29). In this study, casein injection in NCD-fed mice caused systemic inflammation, revealed by significant increases of TNFα and SAA in serum (Table 1). Injection of casein alone had no effect on body weight and serum lipids (Table 1). Serum BuN concentrations and 24 h urinary albumin excretion were similar between the NCD group and the NCD+casein group; only serum creatinine concentrations were increased in NCD+casein mice (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of mice after the 10 week experimental period

| NCD | NCD+Casein | HFD | HFD+Casein | |

| Body weight (g) | 21.85 ± 1.00 | 21.41 ± 0.40 | 25.31 ± 2.12a | 25.51 ± 1.16 |

| Serum SAA (ng/ml) | 19.35 ± 0.81 | 83.26 ± 15.3a | 17.14 ± 5.6 | 86.6 ± 18.28b |

| Serum TNFα (pg/ml) | 4.39 ± 0.44 | 9.55 ± 0.84a | 2.49 ± 0.17 | 11.43 ± 0.86b |

| Serum FFA (mmol/l) | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 1.54 ± 0.12a | 1.15 ± 0.08 |

| Serum TG (mmol/l) | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 1.41 ± 0.04a | 1.01 ± 0.01b |

| Serum BuN (mmol/l) | 7.93 ± 0.18 | 9.02 ± 0.16 | 8.77 ± 0.29 | 11.90 ± 0.59b |

| Serum Creatinine (μmol/l) | 4.86 ± 0.41 | 7.23 ± 0.22a | 5.84 ± 0.43 | 8.64 ± 0.59b |

| Urinary albumin excretion (μg/day) | 9.14 ± 0.62 | 7.66 ± 0.45 | 8.12 ± 0.47 | 12.5 ± 0.48b |

Mice were fed a NCD, NCD plus casein injection (NCD+Casein), HFD, or HFD plus casein injection (HFD+Casein) for 10 weeks. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5 per group.

P < 0.05 versus the NCD group.

P < 0.05 versus the HFD group.

Mice on a HFD exhibited features of obesity and hyperlipidemia, and maintained normal levels of serum cytokines (Table 1). There was no significant change in any of the renal parameters measured in HFD-fed mice compared with NCD-fed mice (Table 1). However, HFD-fed mice that received casein injection had higher concentrations of BuN and creatinine in the serum, and showed significantly increased urinary albumin excretion (Table 1). In addition, casein injection in HFD-fed mice resulted in higher serum cytokine levels and lower serum TG levels (Table 1). These data suggest that the combination of HFD feeding and casein injection aggravates renal injury in mice.

Chronic inflammation induced by casein caused renal ectopic lipid deposition and morphological change

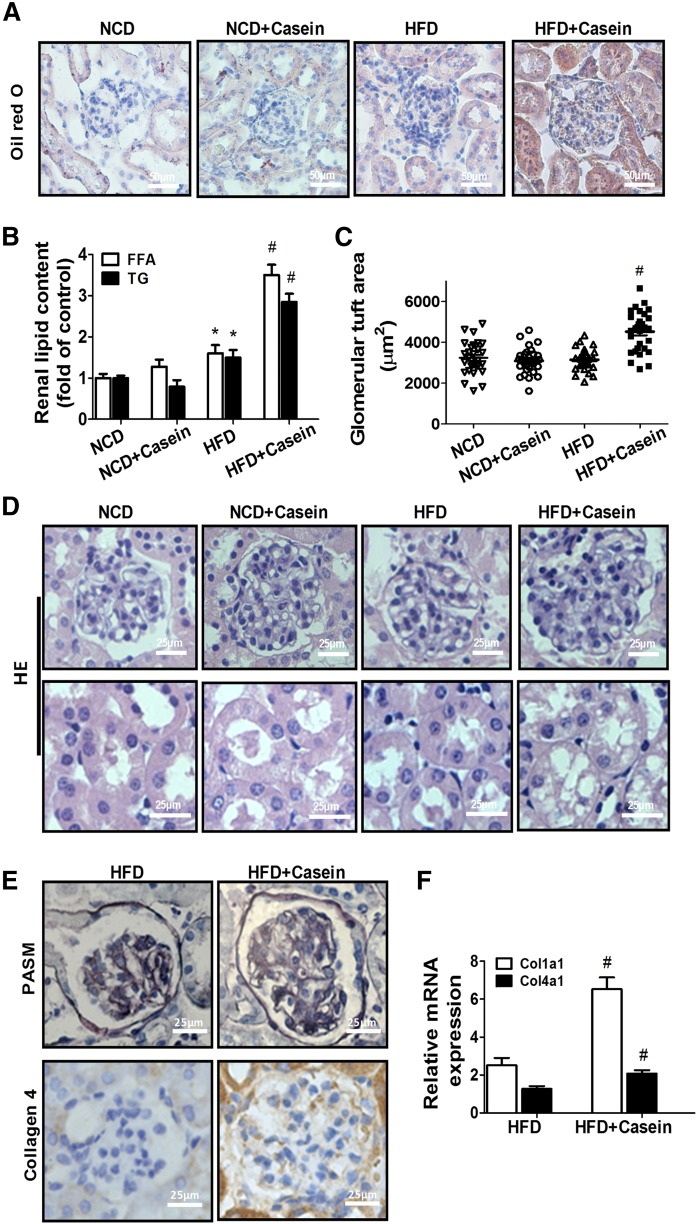

The protein expression of TNFα, IL-6, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) in the kidney of HFD+casein mice was significantly higher than in HFD-fed mice (supplemental Fig. S1A, B). Oil Red O staining and TG/FFA quantitation revealed much more lipid accumulation in the glomeruli and tubules of the kidneys of HFD+casein mice than those of HFD mice (Fig. 1A, B), suggesting that serum lipids may relocate to the kidneys of obese mice under chronic inflammation. In addition, casein injection in NCD-fed mice did not change renal lipid contents (Fig. 1A, B).

Fig. 1.

Chronic inflammation induced by casein-aggravated lipid-mediated renal injury in C57BL/6J mice. Mice were fed a NCD or NCD plus casein injection (NCD+Casein), HFD or HFD plus casein injection (HFD+Casein) for 10 weeks (n = 5). A: Oil Red O-stained kidney sections. B: Quantitative measurement of FFA and TG contents in the kidneys (n = 5). C: Quantitative analysis for glomerular tuft area. [Quantification of the glomerular tuft area was performed in six digital images captured from slides of each mouse stained with HE using Image J 1.47v (n = 5)]. D: Histopathological analysis of kidneys by HE. E: Immunohistochemical detection of PASM and collagen 4. F: Relative renal mRNA expression of Col1α1 and Col4α1 was measured by RT-PCR (n = 5). Values are expressed as folds of the NCD group. *P < 0.05 versus the NCD group, #P < 0.05 versus the HFD group.

Renal histology analysis revealed no obvious morphological change in the mice treated with HFD or casein alone by comparison with the normal NCD-fed mice (Fig. 1C, D), whereas kidney sections from the HFD+casein mice showed glomerulomegaly, disruption of glomerular architecture, and vacuolar degeneration of tubular epithelial cells (Fig. 1C, D). PASM staining showed thickened glomerular basement membrane and increased extracellular matrix in the glomeruli of HFD+casein mice (Fig. 1E). Kidney sections of HFD+casein mice also displayed increased major extracellular matrix protein collagen 4 staining in the glomeruli (Fig. 1E). Additionally, the mRNA expression of Col1α1 and Col4α1 procollagen was increased in HFD+casein mice compared with HFD-fed mice (Fig. 1F). These data, taken together, suggested that chronic inflammation induced by casein initiates the development of obesity-related nephropathy.

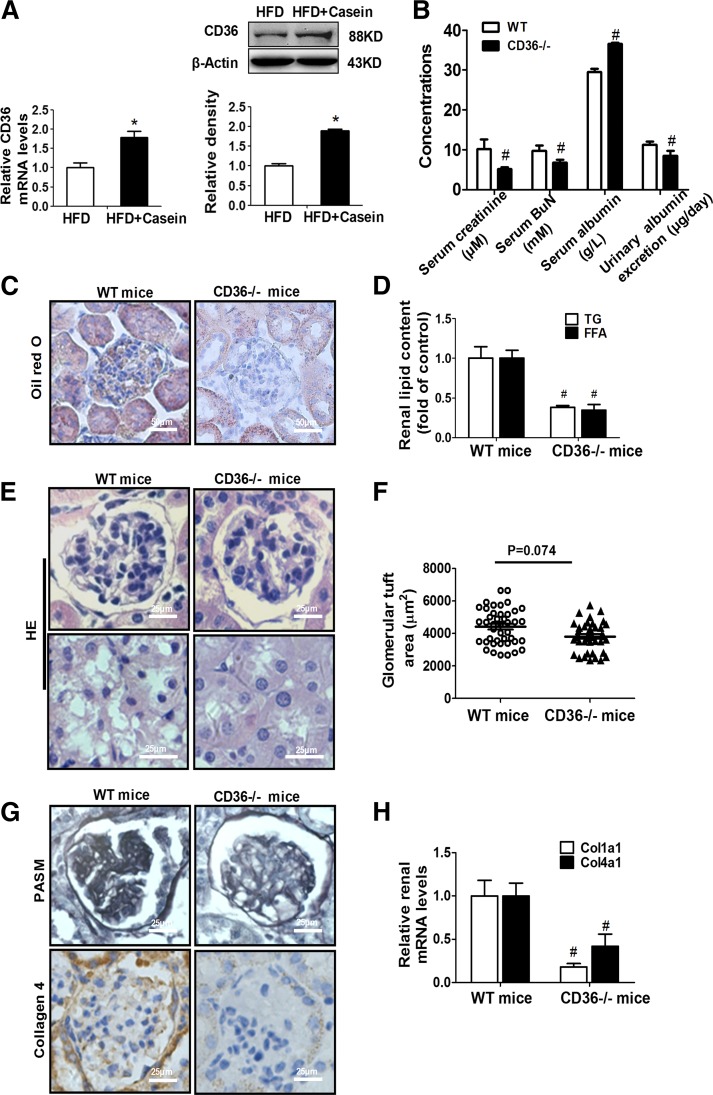

CD36 deficiency prevented renal injury in inflamed mice

The expression of CD36 was significantly increased in the kidney of HFD+casein mice compared with the HFD mice (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, CD36−/− mice were protected from renal dysfunction induced by chronic inflammation, as evidenced by normalized serum parameters (urea nitrogen, creatinine, and albumin) and, especially, decreased 24 h urinary albumin excretion (Fig. 2B). CD36 deficiency in mice eliminated inflammation-induced renal lipid accumulation, which was revealed by Oil Red O staining and the quantitative analysis of TG and FFA levels (Fig. 2C, D). Additionally, CD36 deficiency ameliorated renal pathological changes induced by chronic inflammation, caused a decreasing trend in glomerular size, eliminated vacuolar degeneration of tubular epithelial cells, reduced mesangial expansion, and decreased extracellular matrix content (Fig. 2E–H). These data demonstrated that deficiency of CD36 in mice prevents the development of renal injury induced by inflammation.

Fig. 2.

CD36−/− mice showed ameliorated kidney injury under chronic inflammation. A: The mRNA and protein levels of CD36 in the kidneys from HFD and HFD+Casein mice were determined by RT-PCR (n = 5) and Western blot (one of three representative experiments is shown).*P < 0.05 versus the HFD group. B: Age-matched C57BL/6J (WT) and CD36−/− mice were fed with HFD plus casein injection for 10 weeks (n = 5). Renal parameters were measured in WT and CD36−/− mice (n = 5). C: Oil Red O staining of kidney sections from WT and CD36−/− mice. D: Quantitative analysis of FFA and TG contents in the kidneys from WT and CD36−/− mice (n = 5). E: Representative features of HE-stained kidney sections from WT and CD36−/− mice. F: Quantitative analysis for glomerular tuft area in the WT and CD36−/− mice (n = 5). G: PASM and collagen 4 staining of kidney sections from WT and CD36−/−mice. H: Relative renal mRNA levels for Col1α1 and Col4α1 were determined in WT and CD36−/− mice by RT-PCR (n = 5). #P < 0.05 versus the WT mice.

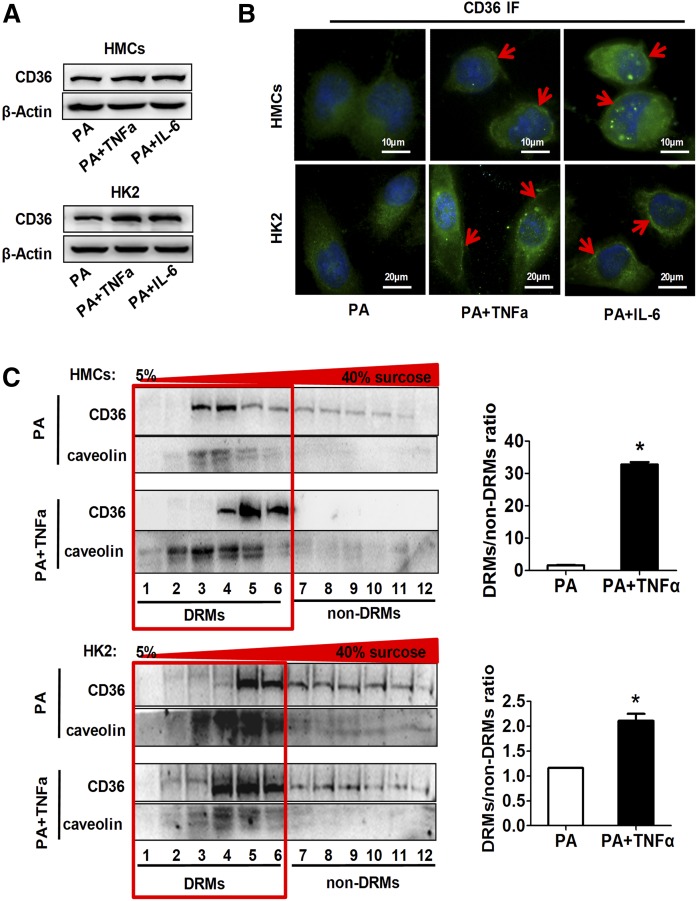

Inflammatory stress upregulated CD36 expression and promoted its location in membrane raft in vitro

The total protein levels of CD36 detected by Western blot were increased by inflammatory cytokine treatment in both HMCs and HK2 cells (Fig. 3A). By using immunofluorescence, we found a membrane localization of CD36 in HMCs and HK2 cells treated with inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3B). Then, the effects of inflammatory cytokines on CD36 distribution in lipid rafts, a key membrane microdomain determining CD36 functions (30), were detected by DRM analysis. The CD36 protein in the TNFα-treated groups was highly enriched in the DRM fractions, marked by caveolin, a lipid raft marker. In contrast, the CD36 protein in the control group was less evident within the DRM fractions and showed higher amounts within the non-DRM fractions (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that inflammatory stress not only increases CD36 expression, but also increases its distribution in membrane rafts.

Fig. 3.

Effects of inflammatory stress on CD36 expression and its subcellular localization. HMCs and HK2 cells were treated with serum-free medium containing PA (0.04 mmol/l) alone or with TNFα (25 ng/ml) or IL-6 (20 ng/ml) for 24 h. Western blot analysis (A) and immunofluorescence (B) of CD36 expression in HMCs and HK2 cells. One of three representative experiments is shown. C: Cell lysates were subjected to sucrose density fractionation by ultracentrifugation. Equal protein amounts from each fraction were analyzed by Western blot analysis with both CD36 (70-100KD) and caveolin (25-35KD) antibody. One of three representative experiments is shown. The ratio of CD36 expression in DRMs to non-DRMs is shown. *P < 0.05 versus the PA only group.

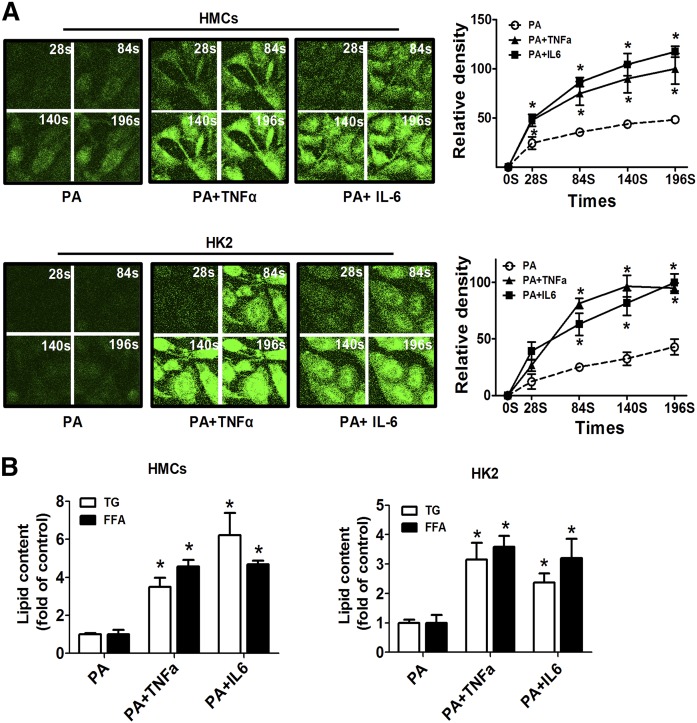

Inflammatory stress increased fatty acid uptake and exacerbated intracellular lipid accumulation

It has been demonstrated that CD36-mediated LCFA uptake requires its localization to plasma lipid rafts (30). We determined the effects of inflammatory stress on the cellular uptake for LCFA. Cells were loaded with a fluorescent fatty acid analog BODIPY-C16, and the uptake rate of fluorescent LCFA was determined using fluorescent microscopy. In both HMCs and HK2 cells, TNFα and IL-6 treatment accelerated the efficiency of fluorescent LCFA uptake into cells (Fig. 4A). The quantitative analysis of cellular TG and FFA revealed increased lipid accumulation in HMCs and HK2 cells after inflammatory cytokine treatment (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that inflammatory stress may aggravate lipid accumulation by accelerating fatty acid uptake.

Fig. 4.

Effects of inflammatory stress on cellular uptake and intracellular accumulation of FFA. HMCs and HK2 cells were treated with serum-free medium containing PA alone or with TNFα or IL-6 for 24 h. A: Then, cells were incubated with BODIPY-C16 (20 μM) followed by a confocal microscope analysis at the time indicated. One of four representative experiments is shown. B: Quantitative analysis of intracellular FFA and TG contents in HMCs and HK2 cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus the PA only group.

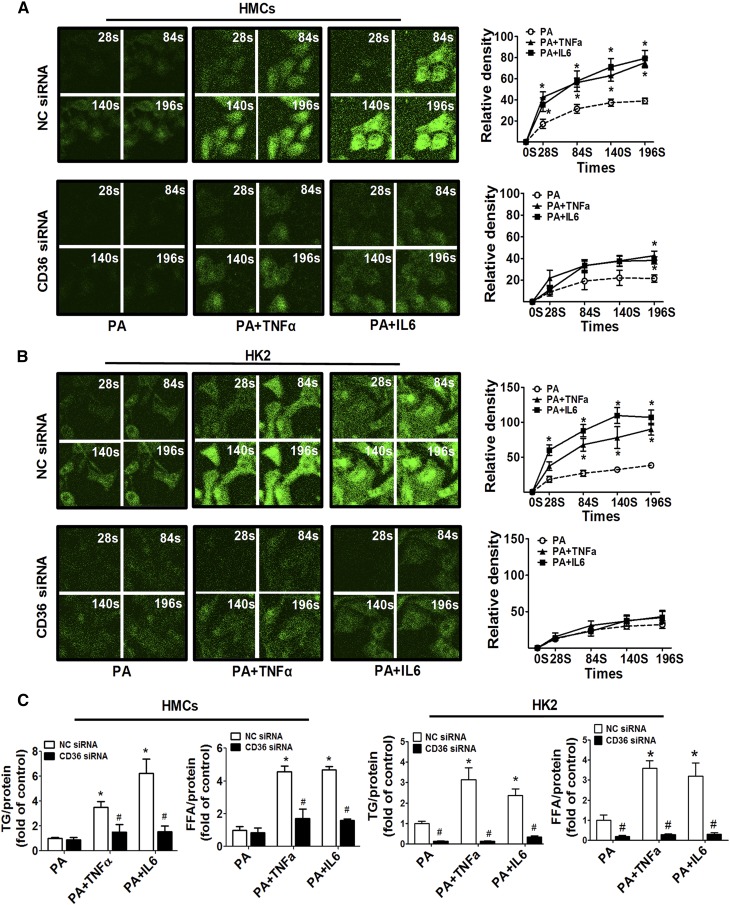

CD36 silencing inhibited fatty acid uptake and lipotoxicity induced by inflammatory stress

To examine the direct role of CD36 in inflammatory stress-mediated lipid accumulation, we silenced the expression of CD36 by transient siRNA transfection. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2A, B, CD36 expression was reduced nearly 4-fold by CD36-siRNA in HMCs and HK2 cells. In the control group, TNFα and IL-6 treatment accelerated fluorescent LCFA uptake in HMCs and HK2 cells, however, the CD36 knockdown largely abrogated the effects of inflammatory cytokines on LCFA uptake (Fig. 5A, B). Additionally, CD36 silence markedly attenuated intracellular TG and FFA accumulation induced by inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Effects of siRNA knockdown of CD36 on inflammatory stress-induced fatty acid uptake. HMCs and HK2 cells were transiently transfected with CD36 siRNA or negative control (NC) siRNA for 24 h, and then the transfected cells were treated with PA alone or with TNFα (25 ng/ml) or IL-6 (20 ng/ml) for another 24 h. The effect of CD36 siRNA on BODIPY-labeled PA uptake under inflammatory stress was determined by confocal microscope in HMCs (A) and HK2 (B) cells. One of four representative experiments is shown. C: The effects of CD36 siRNA on intracellular FFA and TG accumulation under inflammatory stress were determined. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus the PA group, #P < 0.05 versus the NC siRNA group.

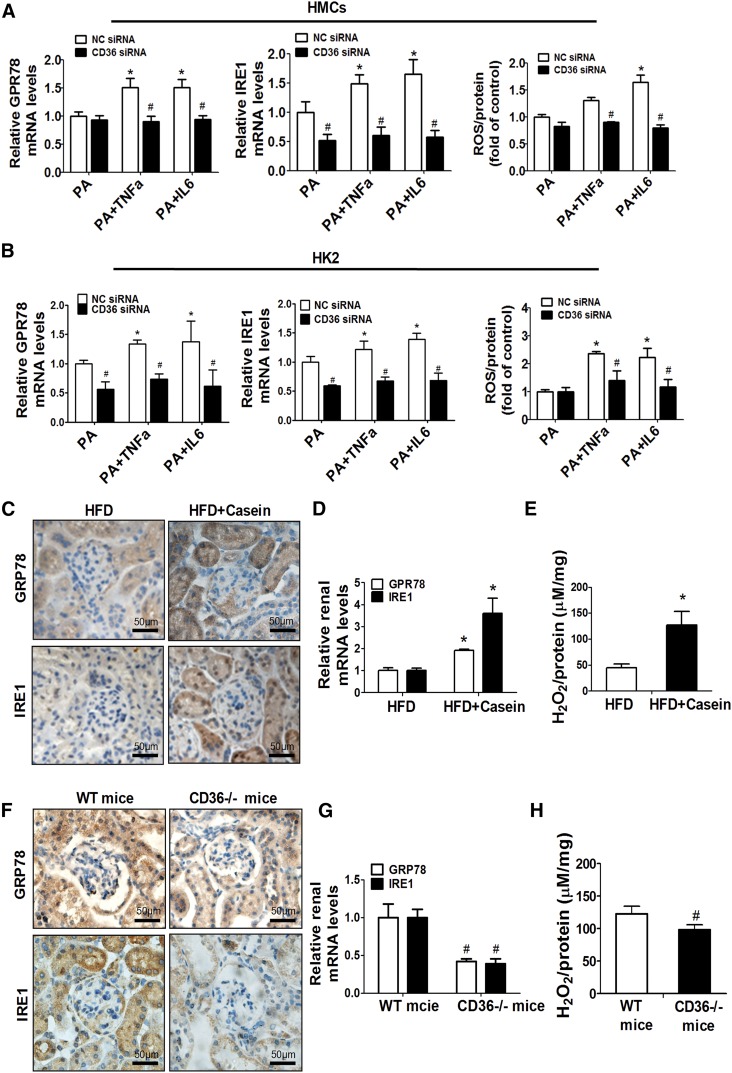

Lipid accumulation has direct toxic effects on renal cells by initiating endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and oxidative stress (31). ER stress and oxidative stress were enhanced by either TNFα or IL-6 treatment in both HMCs and HK2 cells, as demonstrated by increased mRNA expression of ER stress-related genes, Grp78 and Ire1, and increased production of ROS (Fig. 6A, B). However, when CD36 was silenced in those cells, inflammatory cytokines failed to induce ER stress or oxidative stress (Fig. 6A, B). Similarly, in vivo quantification of GRP78 and IRE-1 protein and gene expression by immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR revealed the increased ER stress in the kidney of HFD+casein mice compared with the HFD mice (Fig. 6C, D). The production of H2O2 was also increased by casein injection in HFD-fed mice compared with HFD-fed mice (Fig. 6E). Additionally, ER stress and oxidative stress were significantly decreased in the kidneys of CD36−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 6F–H). These data suggested that inflammatory stress may trigger lipotoxicity via the CD36-dependent pathway.

Fig. 6.

Effects of CD36 silencing on inflammatory stress-induced lipid toxicity. HMCs and HK2 cells were transiently transfected with CD36 siRNA or NC siRNA for 24 h, and the transfected cells were treated with PA alone or with TNFα or IL-6 for another 24 h. The effects of CD36 siRNA on mRNA expression of Grp78 and Ire1, and the production of ROS in HMCs (A) and HK2 (B) cells were measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus the PA group. #P < 0.05 versus the NC siRNA group. Mice were fed a HFD or HFD plus casein injection for 10 weeks (n = 5). C: Expression of GRP78 and IRE1 in the kidney was determined by immunohistochemical analysis. D: Relative renal mRNA expression of GRP78 and IRE1 was measured by RT-PCR (n = 5). E: The concentrations of H2O2 in the kidneys were determined. *P < 0.05 versus the HFD group. WT and CD36−/− mice were fed a HFD plus casein injection for 10 weeks (n = 5). F: Immunohistochemical staining of kidney sections from WT and CD36−/− mice. G: The mRNA expression of GPR78 and IRE1 was determined in WT and CD36−/− mice (n = 5). H: The concentrations of H2O2 in the kidneys from WT and CD36−/− mice were analyzed (n = 5). #P < 0.05 versus the WT mice.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of our current study was to clarify the role of inflammatory stress in obesity-induced renal disease. Here, we show that: 1) inflammatory stress induces renal lipid accumulation by promoting fatty acid uptake, as well as renal injury and systemic alterations; and 2) these abnormalities under inflammation are ameliorated in CD36−/− mice.

Feeding a HFD to mice is known to induce various systemic alterations, including obesity, hyperglycemia, and abnormal lipid profile, as well as renal alterations including albuminuria and glomerular lesions (32). A HFD (60% fat) that is designed to induce these systemic and renal abnormalities usually requires a long treatment duration from 12 to 16 weeks, as previously reported (32–34). Under our experimental conditions, mice with a HFD (60% fat) alone for 10 weeks exhibited apparent phenotypes of obesity and hyperlipidemia, without the appearance of systemic inflammation and renal injury. Casein injection in conjunction with a HFD induced chronic inflammation, causing renal lipid disorder and subsequent renal damage. However, casein injection in NCD-fed mice had no effect on lipid accumulation and did not cause apparent renal injury. Inflamed HFD mice showed renal pathophysiological alterations, including renal lipid accumulation, glomerulomegaly, mesangial expansion, extracellular matrix deposition, and vacuolar degeneration of tubular epithelial cells, which are similar to those observed in patients with early stage ORG. Thus, our data suggest that inflammation acts as a pathogenic factor in the development of obesity-associated renal injury.

Cellular lipotoxicity, which involves the cellular accumulation of nonesterified FFA and TG (20), is thought to contribute to organ dysfunction, including renal disease. The “lipid nephrotoxicity hypothesis” was first proposed by Moorhead et al. (35) in 1982, which stimulated large studies of the relationship between lipids and renal disease. Evidence accumulated in experimental animals and humans suggests a direct role of lipids in the initiation and progression of CKD (36–38). There is sufficient evidence that ectopic lipid is associated with structural and functional changes of renal mesangial and epithelial cells to propose the development of obesity-related CKD (39). Our previous studies described a role of inflammatory stress in the modification of cholesterol homeostasis by increasing cholesterol uptake by LDLr, inhibiting cholesterol efflux by ABCA1, and impairing cholesterol synthesis mediated by HMG-CoA, thereby causing exacerbated cholesterol ester accumulation and foam cell formation in mice fed with a high-cholesterol diet (29, 40). Based on previous studies, this research focused on the effects of inflammatory stress on fatty acid metabolism and lipid accumulation in the kidney.

Fatty acid homeostasis is regulated by a complex interplay between plasma nonesterified fatty acid uptake and de novo fatty acid on the one hand, as well as fatty acid oxidation and TG export by VLDLs on the other hand. Renal steatosis develops when the rate of fatty acid input (uptake and synthesis) exceeds the rate of fatty acid output (oxidation and secretion). Previous research has revealed that inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can decrease fatty acid oxidation and nuclear hormone receptors, which may be one reason why LPS leads to FFA and TG accumulation in the kidney (41–43). In comparison with LPS-induced mouse models, casein injection induces a lower degree inflammatory stress characterized by increased multiple cytokines (IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-6) and SAA levels in serum, which is more likely to mimic the chronic systemic inflammatory state observed in patients. In our study, chronic inflammation induced by casein injection promoted lipid accumulation in the kidney of HFD-fed mice, which was accompanied by increased CD36 expression. Our results update the lipid nephrotoxicity hypothesis by describing how inflammatory stress alters lipid homeostasis by increasing fatty acid uptake mediated by fatty acid translocase, CD36.

CD36 belongs to a scavenger receptor, regulating inflammatory responses to conduct signals and activate inflammatory pathways (44, 45). For its function as a facilitator of the inflammatory response, it has become increasingly clear that CD36 is associated with kidney diseases. A study by Okamura et al. (26) showed a protective role for CD36 deletion in renal fibrogenesis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction, through attenuating the proinflammatory pathway. A novel peptide that antagonizes CD36 was recently reported to ameliorate renal inflammation and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and slow the progression of CKD in the mouse model of unilateral ureteral obstruction and 5/6 nephrectomy (46). Despite this body of evidence, key questions about CD36 as a fatty acid transporter involved in the development of obesity-related CKD are unanswered. Our results suggest that CD36 is a checkpoint that regulates lipid nephrotoxicity under inflammatory stress. We found that deletion of CD36 almost completely reversed ectopic renal lipid deposition in obese mice bearing inflammation and prevented the development of renal injury. In vitro, silencing of CD36 largely abrogated inflammatory cytokine-induced fatty acid uptake, intracellular FFA and TG accumulation, and cellular stress. Our study suggests that CD36 represents a potential therapy for the amelioration of obesity-related CKD under inflammatory stress.

The ability of CD36 to transport fatty acids not only depends on its protein levels, but is also determined by its locations. Previous works have demonstrated that CD36-mediated LCFA uptake requires its localization to the plasma membrane raft, a special plasma membrane microdomain enriched in cholesterol and glycosphingolipids. Binding of LCFA to CD36 at the plasma membrane occurred only within lipid rafts (30). Our recent study demonstrated that inflammatory stress increases hepatic CD36 translational efficiency by activating the mTOR signaling pathway (47). In this study, we found that inflammatory stress increases CD36 protein expression both in kidney tissue and renal cells. As a result, inflammatory stress eventually increased cellular uptake of LCFA, as well as the deposition of lipid, and also initiated cellular stress response.

In conclusion, inflammatory stress increases fatty acid uptake by modulating renal CD36 expression and membrane location, which subsequently results in ectopic lipid deposition and triggers renal injury. This study indicates that obese patients with chronic inflammation are more prone to develop CKD, and CD36 is a potential therapeutic target for obesity-related CKD.

Note added in proof

In order to avoid conflicts of interest between Chongqing Medical University and University College London Medical School, Drs. Xiong Ruan, Zac Varghese, and John F. Moorhead requested to have their names removed from the author byline after the Papers in Press version of this article was published on May 23, 2017.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Maria Febbraio (Lerner Research Institute) for providing the CD36 knockout mice.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- BuN

- blood urea nitrogen

- CKD

- chronic kidney disease

- DRM

- detergent-resistant membrane

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- HE

- hematoxylin-eosin

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- HK2

- human kidney 2

- HMC

- human mesangial cell

- IL

- interleukin

- LCFA

- long-chain fatty acid

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- NCD

- normal chow diet

- ORG

- obesity-related glomerulopathy

- PA

- palmitic acid

- PASM

- periodic acid-silver methenamine

- SAA

- serum amyloid A

- TG

- triglyceride

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81400786, 81570517, and 81390354 (Key Program) and Chongqing Research Program of Basic Research and Frontier Technology Grants cstc2015jcyjBX0044 and cstc2015jcyjA10001. All the authors declare no competing interests.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wahba I. M., and Mak R. H.. 2007. Obesity and obesity-initiated metabolic syndrome: mechanistic links to chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2: 550–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iseki K., Ikemiya Y., Kinjo K., Inoue T., Iseki C., and Takishita S.. 2004. Body mass index and the risk of development of end-stage renal disease in a screened cohort. Kidney Int. 65: 1870–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu C. Y., McCulloch C. E., Iribarren C., Darbinian J., and Go A. S.. 2006. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 144: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ejerblad E., Fored C. M., Lindblad P., Fryzek J., McLaughlin J. K., and Nyren O.. 2006. Obesity and risk for chronic renal failure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17: 1695–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.St Peter J. V., Hartley G. G., Murakami M. M., and Apple F. S.. 2006. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-BNP in obese patients without heart failure: relationship to body mass index and gastric bypass surgery. Clin. Chem. 52: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIntyre N. 1988. Familial LCAT deficiency and fish-eye disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 11 (Suppl. 1): 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noori N., Hosseinpanah F., Nasiri A. A., and Azizi F.. 2009. Comparison of overall obesity and abdominal adiposity in predicting chronic kidney disease incidence among adults. J. Ren. Nutr. 19: 228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kambham N., Markowitz G. S., Valeri A. M., Lin J., and D’Agati V. D.. 2001. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: an emerging epidemic. Kidney Int. 59: 1498–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuboi N., Utsunomiya Y., and Hosoya T.. 2013. Obesity-related glomerulopathy and the nephron complement. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 28 (Suppl. 4): iv108–iv113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Praga M., Hernandez E., Morales E., Campos A. P., Valero M. A., Martinez M. A., and Leon M.. 2001. Clinical features and long-term outcome of obesity-associated focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 16: 1790–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reaven G. M. 1988. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 37: 1595–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oterdoom L. H., de Vries A. P., Gansevoort R. T., de Jong P. E., Gans R. O., and Bakker S. J.. 2007. Fasting insulin modifies the relation between age and renal function. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 22: 1587–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrero J. J., and Stenvinkel P.. 2009. Persistent inflammation as a catalyst for other risk factors in chronic kidney disease: a hypothesis proposal. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4 (Suppl. 1): S49–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y., Liu Z., Xiang Z., Zeng C., Chen Z., Ma X., and Li L.. 2006. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: insights from gene expression profiles of the glomeruli derived from renal biopsy samples. Endocrinology. 147: 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyamoto T., Carrero J. J., and Stenvinkel P.. 2011. Inflammation as a risk factor and target for therapy in chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 20: 662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma K. L., Ruan X. Z., Powis S. H., Chen Y., Moorhead J. F., and Varghese Z.. 2008. Inflammatory stress exacerbates lipid accumulation in hepatic cells and fatty livers of apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Hepatology. 48: 770–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y., Chen Y., Zhao L., Chen Y., Mei M., Li Q., Huang A., Varghese Z., Moorhead J. F., and Ruan X. Z.. 2012. Inflammatory stress exacerbates hepatic cholesterol accumulation via disrupting cellular cholesterol export. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 27: 974–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao L., Chen Y., Tang R., Chen Y., Li Q., Gong J., Huang A., Varghese Z., Moorhead J. F., and Ruan X. Z.. 2011. Inflammatory stress exacerbates hepatic cholesterol accumulation via increasing cholesterol uptake and de novo synthesis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26: 875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mei M., Zhao L., Li Q., Chen Y., Huang A., Varghese Z., Moorhead J. F., Zhang S., Powis S. H., Li Q., et al. 2011. Inflammatory stress exacerbates ectopic lipid deposition in C57BL/6J mice. Lipids Health Dis. 10: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinberg J. M. 2006. Lipotoxicity. Kidney Int. 70: 1560–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallin T., Ma Z., Ogata H., Jorgensen I. H., Iezzi M., Wang H., Wollheim C. B., and Bjorklund A.. 2010. Facilitation of fatty acid uptake by CD36 in insulin-producing cells reduces fatty-acid-induced insulin secretion and glucose regulation of fatty acid oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1801: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Febbraio M., Hajjar D. P., and Silverstein R. L.. 2001. CD36: a class B scavenger receptor involved in angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and lipid metabolism. J. Clin. Invest. 108: 785–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baines R. J., and Brunskill N. J.. 2011. Tubular toxicity of proteinuria. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 7: 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua W., Huang H. Z., Tan L. T., Wan J. M., Gui H. B., Zhao L., Ruan X. Z., Chen X. M., and Du X. G.. 2015. CD36 mediated fatty acid-induced podocyte apoptosis via oxidative stress. PLoS One. 10: e0127507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Susztak K., Ciccone E., McCue P., Sharma K., and Böttinger E. P.. 2005. Multiple metabolic hits converge on CD36 as novel mediator of tubular epithelial apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy. PLoS Med. 2: e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okamura D. M., Pennathur S., Pasichnyk K., López-Guisa J. M., Collins S., Febbraio M., Heinecke J., and Eddy A. A.. 2009. CD36 regulates oxidative stress and inflammation in hypercholesterolemic CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20: 495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeaiter Z., Cohen D., Müsch A., Bagnoli F., Covacci A., and Stein M.. 2008. Analysis of detergent-resistant membranes of Helicobacter pylori infected gastric adenocarcinoma cells reveals a role for MARK2/Par1b in CagA-mediated disruption of cellular polarity. Cell. Microbiol. 10: 781–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y., Wu T., Wu J., Zhao L., Li Q., Varghese Z., Moorhead J. F., Powis S. H., Chen Y., and Ruan X. Z.. 2013. Chronic inflammation exacerbates glucose metabolism disorders in C57BL/6J mice fed with high-fat diet. J. Endocrinol. 219: 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Z. E., Chen Y., Huang A., Varghese Z., Moorhead J. F., Yan F., Powis S. H., Li Q., and Ruan X. Z.. 2011. Inflammatory stress exacerbates lipid-mediated renal injury in ApoE/CD36/SRA triple knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301: F713–F722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eyre N. S., Cleland L. G., Tandon N. N., and Mayrhofer G.. 2007. Importance of the carboxyl terminus of FAT/CD36 for plasma membrane localization and function in long-chain fatty acid uptake. J. Lipid Res. 48: 528–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruan X. Z., Varghese Z., and Moorhead J. F.. 2009. An update on the lipid nephrotoxicity hypothesis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 5: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deji N., Kume S., Araki S., Soumura M., Sugimoto T., Isshiki K., Chin-Kanasaki M., Sakaguchi M., Koya D., Haneda M., et al. 2009. Structural and functional changes in the kidneys of high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296: F118–F126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang T., Wang Z., Proctor G., Moskowitz S., Liebman S. E., Rogers T., Lucia M. S., Li J., and Levi M.. 2005. Diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J mice causes increased renal lipid accumulation and glomerulosclerosis via a sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 32317–32325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kume S., Uzu T., Araki S., Sugimoto T., Isshiki K., Chin-Kanasaki M., Sakaguchi M., Kubota N., Terauchi Y., Kadowaki T., et al. 2007. Role of altered renal lipid metabolism in the development of renal injury induced by a high-fat diet. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18: 2715–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moorhead J. F., Chan M. K., El-Nahas M., and Varghese Z.. 1982. Lipid nephrotoxicity in chronic progressive glomerular and tubulo-interstitial disease. Lancet. 2: 1309–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamanna V. S., Roh D. D., and Kirschenbaum M. A.. 1998. Hyperlipidemia and kidney disease: concepts derived from histopathology and cell biology of the glomerulus. Histol. Histopathol. 13: 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee P. H., Chang H. Y., Tung C. W., Hsu Y. C., Lei C. C., Chang H. H., Yang H. F., Lu L. C., Jong M. C., Chen C. Y., et al. 2009. Hypertriglyceridemia: an independent risk factor of chronic kidney disease in Taiwanese adults. Am. J. Med. Sci. 338: 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tozawa M., Iseki K., Iseki C., Oshiro S., Ikemiya Y., and Takishita S.. 2002. Triglyceride, but not total cholesterol or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, predict development of proteinuria. Kidney Int. 62: 1743–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vries A. P., Ruggenenti P., Ruan X. Z., Praga M., Cruzado J. M., Bajema I. M., D’Agati V. D., Lamb H. J., Pongrac Barlovic D., Hojs R., et al. 2014. Fatty kidney: emerging role of ectopic lipid in obesity-related renal disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2: 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong S., Zhao L., Li Q., Yang P., Varghese Z., Moorhead J. F., Chen Y., and Ruan X. Z.. 2015. Inflammatory stress exacerbated mesangial foam cell formation and renal injury via disrupting cellular cholesterol homeostasis. Inflammation. 38: 959–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feingold K. R., Wang Y., Moser A., Shigenaga J. K., and Grunfeld C.. 2008. LPS decreases fatty acid oxidation and nuclear hormone receptors in the kidney. J. Lipid Res. 49: 2179–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zager R. A., Johnson A. C., and Hanson S. Y.. 2005. Renal tubular triglyercide accumulation following endotoxic, toxic, and ischemic injury. Kidney Int. 67: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khovidhunkit W., Kim M-S., Memon R. A., Shigenaga J. K., Moser A. H., Feingold K. R., and Grunfeld C.. 2004. Effects of infection and inflammation on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism: mechanisms and consequences to the host. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1169–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverstein R. L., and Febbraio M.. 2009. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci. Signal. 2: re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart C. R., Stuart L. M., Wilkinson K., van Gils J. M., Deng J., Halle A., Rayner K. J., Boyer L., Zhong R., and Frazier W. A.. 2010. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat. Immunol. 11: 155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souza A. C. P., Bocharov A. V., Baranova I. N., Vishnyakova T. G., Huang Y. G., Wilkins K. J., Hu X., Street J. M., Alvarez-Prats A., and Mullick A. E.. 2016. Antagonism of scavenger receptor CD36 by 5A peptide prevents chronic kidney disease progression in mice independent of blood pressure regulation. Kidney Int. 89: 809–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C., Hu L., Zhao L., Yang P., Moorhead J. F., Varghese Z., Chen Y., and Ruan X. Z.. 2014. Inflammatory stress increases hepatic CD36 translational efficiency via activation of the mTOR signalling pathway. PLoS One. 9: e103071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.