Abstract

The trafficking of ion channels to the plasma membrane is tightly controlled to ensure the proper regulation of intracellular ion homeostasis and signal transduction. Mutations of polycystin-2, a member of the TRP family of cation channels, cause autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, a disorder characterized by renal cysts and progressive renal failure. Polycystin-2 functions as a calcium-permeable nonselective cation channel; however, it is disputed whether polycystin-2 resides and acts at the plasma membrane or endoplasmic reticulum (ER). We show that the subcellular localization and function of polycystin-2 are directed by phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein (PACS)-1 and PACS-2, two adaptor proteins that recognize an acidic cluster in the carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2. Binding to these adaptor proteins is regulated by the phosphorylation of polycystin-2 by the protein kinase casein kinase 2, required for the routing of polycystin-2 between ER, Golgi and plasma membrane compartments. Our paradigm that polycystin-2 is sorted to and active at both ER and plasma membrane reconciles the previously incongruent views of its localization and function. Furthermore, PACS proteins may represent a novel molecular mechanism for ion channel trafficking, directing acidic cluster-containing ion channels to distinct subcellular compartments.

Keywords: PACS, polycystin-2, TRPP2

Introduction

Mammalian cells express a diverse repertoire of ion channels that broadly affect cellular homeostasis, mandating tight regulation. Many ion channels carry specific trafficking motifs that regulate their exit from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the trans-Golgi network (TGN), where they are directed to discrete plasma membrane domains to assume a highly compartmentalized distribution (Deutsch, 2003). Several ion channels are retained in the ER by a di-arginine motif until the assembly of a multimeric protein complex masks this retention signal (Ma and Jan, 2002). Other ion channels undergo rapid endocytosis and degradation, allowing only a small number of channel proteins to accumulate at the plasma membrane (Staub et al, 1997). Genetic mutations that disturb the subcellular trafficking of ion channels are often associated with human disease, underlining the importance of spatial regulation (Cheng et al, 1990; Bertrand and Frizzell, 2003; Hebert, 2003; Thomas et al, 2003).

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is caused by the mutation of either PKD1 or PKD2, two genes encoding for the integral membrane proteins polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 (reviewed in Watnick and Germino, 2003). Polycystin-2, a member of the TRP family of ion channels (TRPP2) (reviewed in Montell, 2001; Clapham, 2003), functions as a calcium-permeable, nonselective cation channel (Hanaoka et al, 2000; Gonzalez-Perrett et al, 2001; Luo et al, 2003). Both polycystins are present in the primary cilia of kidney epithelial cells (Pazour et al, 2002; Yoder et al, 2002) and increase intracellular Ca2+ in response to cilial bending (Nauli et al, 2003). Polycystin-2 is present at the basolateral plasma membrane of developing renal tubules (Foggensteiner et al, 2000) and on the surface of several cell lines (Luo et al, 2003). Opposing these findings are reports that polycystin-2 is a Ca2+-activated Ca2+ release channel in the ER, as a short motif in the carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2 localizes this protein to the ER (Cai et al, 1999; Koulen et al, 2002; Cai et al, 2004). Here we report that the subcellular localization and function of polycystin-2 is regulated by phosphofurin acidic cluster sorting protein (PACS)-1 and PACS-2, two sorting proteins that recognize an acidic cluster in the carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2. Blocking the binding to both PACS-1 and PACS-2 localizes a functional polycystin-2 to the plasma membrane. Interaction with these adaptor proteins is regulated by the phosphorylation of polycystin-2 by the protein kinase casein kinase 2 (CK2). Our observations indicate that polycystin-2 is not exclusive to ER or plasma membrane; it traffics to both. We therefore propose a dual role for polycystin-2 at both ER and plasma membranes. Lastly, the presence of acidic clusters within many ion channels, including other TRP channels such as TRPV4, suggests a broad and important role for PACS proteins in the sorting of ion channels to cellular compartments.

Results

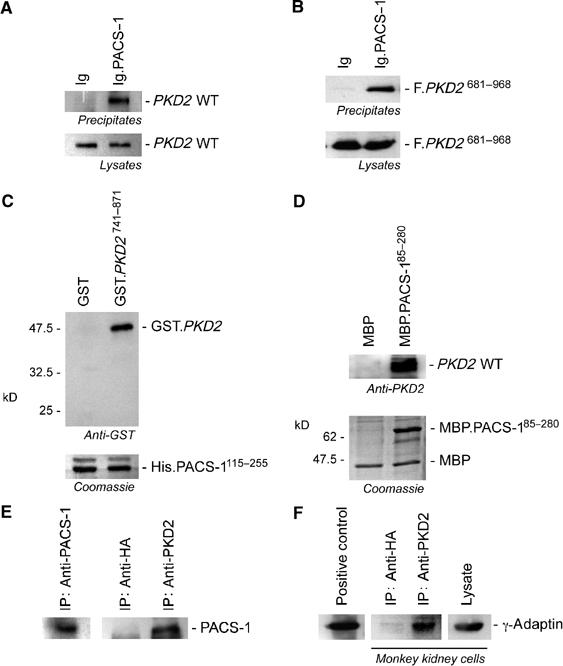

Polycystin-2 interacts with the connector protein PACS-1

Analysis of the carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2 revealed a highly conserved acidic cluster in all mammalian polycystin-2 proteins, but not in the polycystin-2-like proteins. Acidic clusters act as sorting motifs that direct the localization of membrane proteins in the TGN/endosomal system. Sorting is directed by connector proteins that recognize and bind phosphorylated acidic clusters (Gu et al, 2001; Tekirian, 2002). A phosphorylatable residue within the acid cluster, typically a CK2 site, facilitates such cargo trafficking. Since a CK2 site is present in the mammalian polycystin-2 proteins, we decided to investigate whether the subcellular localization of mammalian polycystin-2 is directed by connector proteins that recognize phosphorylated acidic clusters. Presently, two types of connector proteins are known to recognize phosphorylatable acidic clusters, the gamma-ear containing ARF binding (GGA) and the PACS adaptor proteins (reviewed in Gu et al, 2001; Tekirian, 2002). The lack of an adjacent di-leucine motif, typical for GGA recognition (Kato et al, 2002a), was evidence that polycystin-2 interacts with PACS-1 rather than with GGA-type proteins. PACS-1 is a cytosolic furin-sorting molecule that associates with the adaptor protein complex-1 (AP-1) and forms a ternary complex between furin and AP-1 (Wan et al, 1998; Crump et al, 2001). As shown in Figure 1A, PACS-1 fused to an immunoglobulin tag (Ig.PACS-1) precipitated either wild-type (WT) polycystin-2 or F.PKD2681–968, the Flag-tagged carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2 containing the acidic cluster (Figure 1B). The interaction between PACS-1 and the carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2 was direct, as demonstrated by the in vitro interaction of recombinant PACS-1 and polycystin-2 proteins (Figure 1C). Recombinant PACS-1 also recognized endogenous polycystin-2 from mouse kidneys (Figure 1D), an interaction that was unaffected by a recombinant polycystin-1 containing the polycystin-2-binding domain (data not shown). Furthermore, polycystin-2 formed complexes with both endogenous PACS-1 and the γ subunit of AP-1 (Figure 1E and F), indicating that PACS-1 forms a ternary complex between polycystin-2 and AP-1, independent of polycystin-1.

Figure 1.

The carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2 interacts with the PACS-1/γ-adaptin protein complex. (A) PACS-1, fused to the immunoglobulin tag (Ig.PACS-1), precipitates WT polycystin-2 (PKD2 WT) from transiently transfected HEK 293T cells. (B) The same PACS-1 fusion protein interacts with a Flag-tagged polycystin-2 truncation that contains the carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin (F.PKD2681–968), demonstrating that PACS-1 recognizes a motif in the carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2. (C) The recombinant HIS-tagged furin-binding region of PACS-1 (HIS.PACS-1115–255) binds a recombinant GST-tagged polycystin-2 fragment containing amino acids 741–871 (GST.PKD2741–871) in vitro (upper panel). Equal loading of the HIS.PACS-1115–255 is shown in the lower panel by Coomassie blue staining. (D) A recombinant PACS-1 protein (amino acids 85–280) containing the maltose-binding protein (MBP) (MBP.PACS-185–280) immobilizes polycystin-2 from mouse kidney lysates, demonstrating that native polycystin-2 recognizes and binds PACS-1. (E) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous polycystin-2 from COS M6 kidney cells immobilizes PACS-1. (F) Endogenous γ-adaptin can be co-immunoprecipitated from COS M6 kidney cells using a polycystin-2-specific antiserum, indicating that polycystin-2 associates with the AP1 adaptor complex.

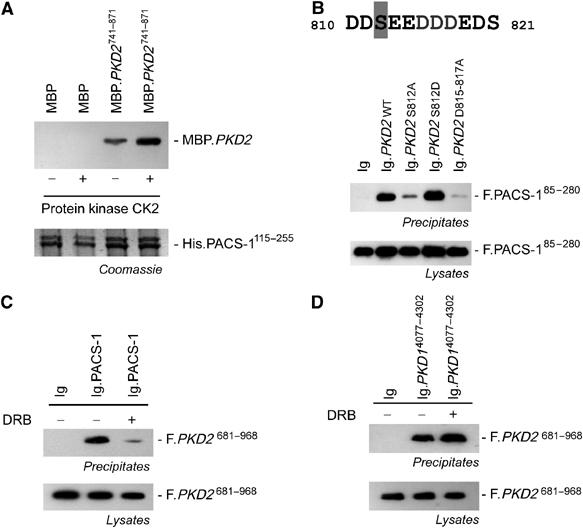

Interaction between PACS-1 and polycystin-2 is phosphorylation-dependent

The PACS-1-binding domain of furin (EECPS773 DS775 EEDE) contains a pair of protein kinase CK2 sites (Molloy et al, 1994; Jones et al, 1995), two serines that when phosphorylated greatly enhance the interaction of PACS-1 with furin (Wan et al, 1998). Serine 812 within the carboxy-terminal acidic cluster of polycystin-2 is a candidate CK2 site (Figure 2); we postulated that the phosphorylation state of this site regulates the interaction between PACS-1 and polycystin-2. As seen in Figure 2A, phosphorylation of recombinant polycystin-2 by CK2 enhanced the binding of PACS-1. Similarly, an S-to-D mutation at position 812, mimicking constitutive phosphorylation, maintained the interaction between PACS-1 and the carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2, whereas replacement of serine 812 by alanine or destruction of the acid cluster of polycystin-2 (PKD2 D815-17A mutation) greatly diminished their interaction (Figure 2B). The association between immunoglobulin-tagged PACS-1 and a Flag-tagged carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2 was also abrogated by the CK2 inhibitor 5,6-dichloro-1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-benzimidazole (DRB) (Figure 2C) (Zandomeni et al, 1986), further demonstrating the requisite phosphorylation of serine 812 for efficient binding of PACS-1 to polycystin-2. In contrast, DRB had no effect on the interaction of polycystin-1 with polycystin-2 (Figure 2D). These results demonstrate that PACS-1 recognizes and binds to polycystin-2 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

The interaction between PACS-1 and polycystin-2 is direct and requires phosphorylation of S812 of polycystin-2 for efficient binding. (A) The HIS-tagged furin-binding region of PACS-1 (amino acids 115–255) binds the carboxy-terminal amino acids 741–871 of polycystin-2 fused to the MBP. Phosphorylation of the recombinant MBP-polycystin-2 fusion protein (MBP.PKD2741–871) results in significantly increased binding in vitro. The Coomassie blue staining (lower panel) shows that equal amounts of HIS-PACS-1 were used to immobilize the polycystin-2 fusion protein. (B) Mutation of serine 812 to alanine (PKD2 S812A) or destruction of the acidic cluster (PKD2 D815-817A), but not the serine 812 to aspartic acid mutation abrogates the interaction between polycystin-2 and PACS-1. HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected as indicated, and the carboxy-terminal domain of WT or mutant polycystin-2 fused to the sIg7 tag was precipitated to monitor binding of Flag-tagged PACS-1 (amino acids 85–280). (C) A specific inhibitor of protein kinase CK2, DRB, abrogated the interaction between immunoglobulin-tagged PACS-1 and the Flag-tagged carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2. DRB was added at a concentration of 30 μM for 4 h to transiently transfected HEK 293T cells. Ig.PACS-1 was precipitated from lysates using protein G; the Flag-specific M2 antibody was used to detect immobilized polycystin-2. (D) DRB does not have an effect on the interaction between polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. The Flag-tagged carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2 (F.PKD2) interacts with the carboxy-terminus of polycystin-1 fused to the sIg7 tag. Addition of DRB had no effect on this interaction.

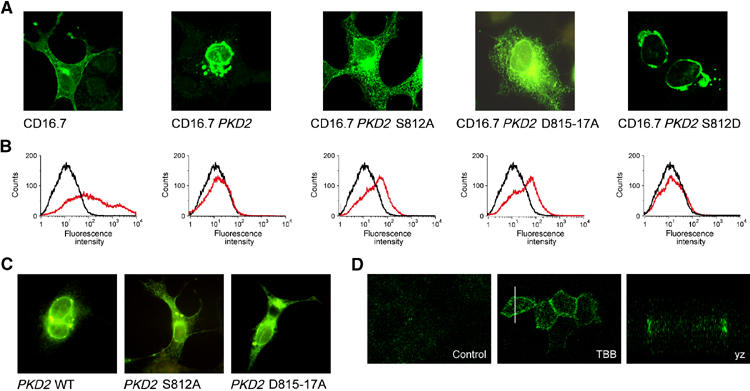

The acidic cluster regulates the subcellular localization of polycystin-2

Mutation of the CK2 phosphorylation site or the acidic cluster of polycystin-2 had profound effects on its localization. The carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic domain of polycystin-2 fused to a transmembrane protein (CD16.7) was retained in the ER of transiently transfected COS M6 cells (Figure 3A and B). Mutation of the critical serine (S812A) of the candidate CK2 phosphorylation site within the acidic cluster altered the subcellular localization of the carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2 from ER to cell surface. A similar redistribution of the polycystin-2 carboxy-terminus was achieved by replacing three aspartic acids of the acidic cluster with alanine (D815-17A). As expected, the S812D mutation, a construct with an enhanced PACS-1-binding capacity, was retained in the ER. Changes in subcellular localization were less striking for full-length polycystin-2 mutants. Nevertheless, in a significant portion of transiently transfected cells, mutation of either S812A or D815-17A released polycystin-2 from the ER compartment and facilitated its translocation to the plasma membrane, whereas WT polycystin-2 was retained in the ER (Figure 3C). To determine whether CK2 regulates basolateral targeting of polycystin-2, we examined polarized MDCK cells by confocal microscopy after incubation with the specific CK2 inhibitor 4,5,6,7-tetrabromo-2-azabenzimidazole (TBB, 20 μM, 4 h). As shown in Figure 3D, polycystin-2 is scarcely present at the surface of nonpermeabilized MDCK cells stably expressing Tac-PKD2. After treatment with TBB, polycystin-2 appeared at the lateral membrane, but not the apical or basal membrane. No change in cilial expression was detected (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Subcellular localization of polycystin-2. (A) The subcellular localization of the carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2, fused to the extracellular domain of CD16 and the transmembrane domain of CD7, was compared to either control protein (CD16.7) or the polycystin-2 mutants CD16.7 PKD2 S812A, CD16.7 PKD2 S812D and CD16.7 PKD2 D815-17A in transiently transfected COS M6 cells labelled with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD16 antibody. (B) FACS analysis was performed with nonpermeabilized cells to determine the surface expression of the CD16.7 fusion proteins. In addition to the control protein CD16.7, only CD16.7 PKD2 S812A and CD16.7 PKD2 D815-17A were detectable at the cell surface (black curves, control; red curves, transfected cells). (C) The subcellular localization of full-length polycystin-2 or the S812A and D815-17A mutants of polycystin-2 in transiently transfected COS M6 cells was determined using a polycystin-2-specific rabbit antiserum followed by an FITC-labelled anti-rabbit antiserum. Polycystin-2 showed the typical perinuclear accumulation, whereas both the polycystin-2 S812A and the D815-17A mutations assumed a more dispersed punctate distribution and some membrane staining. (D) Surface labelling of nonpermeabilized, polarized MDCK cells. Polycystin-2702–968 containing an extracellular Tac tag is translocated to the lateral membrane after treatment with a specific inhibitor of CK2 (TBB, 20 μM, 4 h).

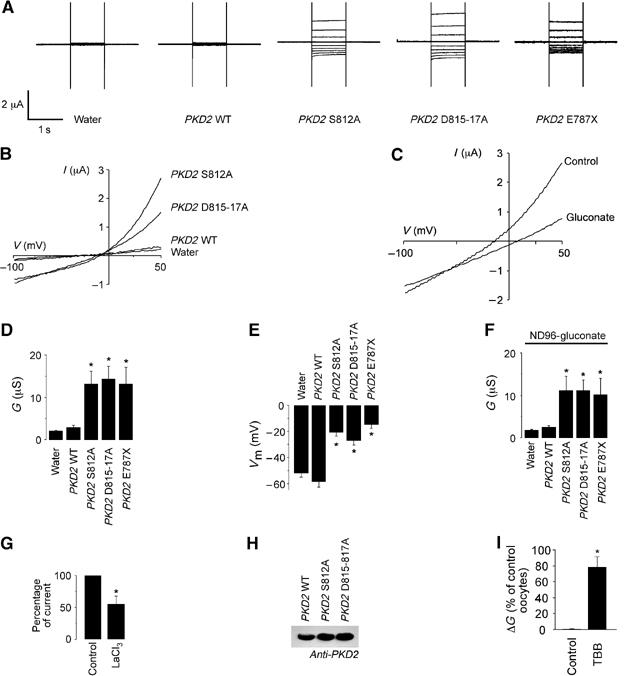

Disruption of the acidic cluster increases ion channel activity of polycystin-2

Since WT polycystin-2 does not exit the ER nor produce whole cell currents in Xenopus oocytes and CHO cells (Hanaoka et al, 2000; Chen et al, 2001), we investigated whether generating PKD2 mutants defective in PACS-1 binding would result in polycystin-1-independent ion channel activity at the plasma membrane. Whole cell currents of Xenopus laevis oocytes, microinjected with water, WT PKD2, the S812A or the D815-17A mutant of PKD2, were recorded using a standard two electrode voltage clamp. Both the PKD2 S812A and PKD2 D815-17A mutations produced a significant increase in whole cell currents, characterized by a current–voltage relationship closely resembling that generated by the polycystin-1/polycystin-2 complex (Hanaoka et al, 2000; Figure 4A and B). Disruption of PACS-1 binding by the PKD2 S812A and D815-17A mutations, or the PKD2 E787X truncation increased whole cell conductance from 3.1±0.52 μS (n=21) in oocytes expressing WT PKD2 to 13.5±3.2 μS (n=25), 14.5±2.9 μS (n=36) and 13.4±3.8 μS (n=19), respectively (Figure 4D). In contrast, the S812D mutation had no effect on whole cell conductance (data not shown). The membrane potential was depolarized from −58.6±3.7 mV (n=21) in oocytes expressing WT PKD2 to −21±3.2 mV (n=25, PKD2 S812A), −27.4±3.3 mV (n=36, PKD2 D815-17A) and −14.8±2.9 mV (n=19, PKD2 E787X) (Figure 4E). The slight outward rectification of the current induced by the PKD2 mutants was likely the result of the endogenous Ca2+-activated chloride (Cl−) channel in Xenopus oocytes, a channel commonly used as a readout for increased Ca2+ permeability. Hence, the complete removal of extracellular Cl− abolished outward rectification and shifted the reversal potential to positive values (Figure 4C). However, the whole cell conductance in the negative voltage range was still significantly increased even in the absence of extracellular Cl− (ND96-gluconate) (Figure 4F). The reduction of extracellular Na+ from 96 to 10 mM (ND96-NMDG solution) resulted in a significant decrease of whole cell conductance by 1.54±0.4 μS (n=21, PKD2 S812A), 2.44±0.63 μS (n=28, PKD2 D815-17A) and 2.21±0.45 μS (n=13, PKD2 E787X). Lanthanum, an inhibitor of nonselective cation channels, inhibited the currents produced by the PKD2 S812A mutant (Figure 4G). Western blot analysis revealed that the changes in whole cell currents were not the result of different protein levels (Figure 4H). To further substantiate the critical role of CK2-dependent phosphorylation, Xenopus oocytes were preincubated with the CK2 inhibitor TBB (20 μM, 3–6 h). TBB significantly increased the whole cell conductance of oocytes expressing polycystin-2 (Figure 4I), controlling for the increased permeability of control oocytes. These results demonstrate that polycystin-2 functions as a Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channel in the plasma membrane upon release from its interaction with PACS-1.

Figure 4.

The acidic cluster of polycystin-2 affects whole cell currents in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Measurements of current (I) in oocytes injected with water, PKD2 WT, PKD2 S812A, PKD2 D812-817A and PKD2 E787X. Voltage was clamped between −100 and +60 mV (increments of 20 mV for 1 s). (B) Current–voltage (I–V) relationship of PKD2 WT and mutants. (C) I–V relationship of an oocyte expressing PKD2 S812A after replacement of extracellular Cl− by gluconate. (D) Whole cell conductance (G; determined from −100 to 0 mV) of oocytes injected with water (n=49), PKD2 WT (n=21), PKD2 S812A (n=25), PKD2 D815-817A (n=36) or PKD2 E787X (n=12). In contrast to PKD2 WT, expression of PKD2 mutants with a disrupted PACS-1-binding motif significantly increased the whole cell conductance and (E) depolarized the membrane potential (Vm) of injected oocytes (water n=46, PKD2 WT n=19, PKD2 S812A n=22, PKD2 D815-817A n=35, PKD2 E787X n=12). (F) The whole cell conductance remained significantly increased by the PKD2 mutants in the absence of extracellular chloride (Cl−) (ND96-gluconate) (PKD2 WT n=23, PKD2 S812A n=25, PKD2 D815-817A n=35, PKD2 E787X n=10). (G) Lanthanum (500 μM) partially inhibited the whole cell conductance of oocytes injected with PKD2 S812A (n=10). (H) Equal expression of different PKD2 full-length constructs was confirmed by Western blot (five oocytes were pooled for each condition). (I) Preincubation of oocytes expressing PKD2 WT with the specific CK2 inhibitor TBB (20 μM, 3–6 h) significantly increased the conductance (ΔG) compared to water-injected oocytes treated with TBB. Asterisks indicate statistical significance with P<0.05.

PACS-2, a novel PACS protein, localizes polycystin-2 to the endoplasmic reticulum

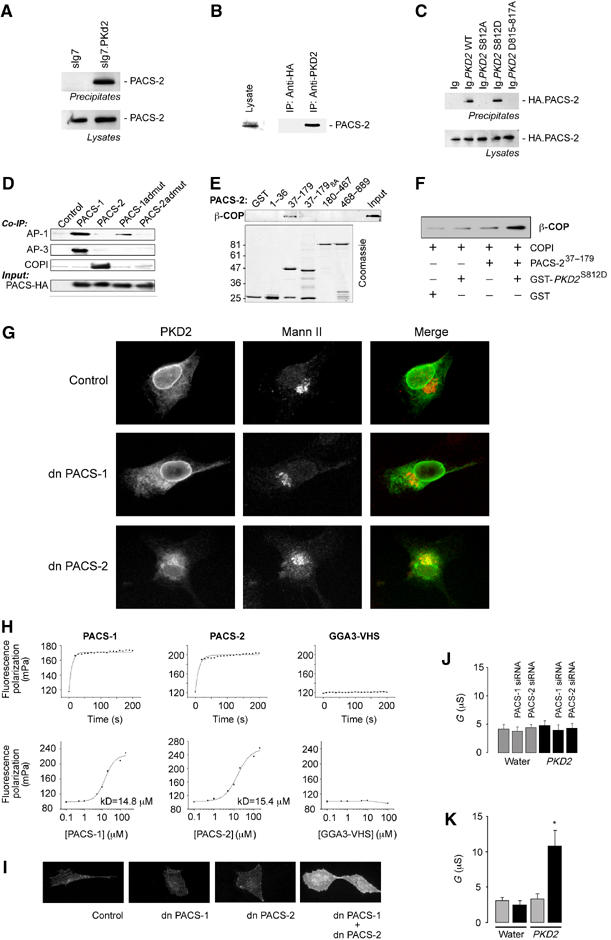

Upon evaluating the role of PACS-1 in targeting polycystin-2 to the plasma membrane, we observed that PACS-1admut, a dominant-negative (dn) PACS-1 (Crump et al, 2001), failed to alter the subcellular localization of polycystin-2 (Figure 5), demonstrating that PACS-1 alone was not decisive in polycystin-2 distribution. Blast searches with PACS-1 identified a novel adaptor protein, termed PACS-2, that is highly homologous to PACS-1, but localizes to the ER (Simmen et al, 2005). This implicates PACS-2 as a regulator of the ER localization of polycystin-2. PACS-2 interacted with transiently overexpressed polycystin-2 in HEK 293T cells and with endogenous protein (Figure 5A and B). The interaction between polycystin-2 and PACS-2 is direct (data not shown), and is mediated by the identical acidic motif that binds to PACS-1 (Figure 5C). To characterize PACS-2 more, we examined vesicular coat preferences for PACS-1 and PACS-2 (Figure 5D). Co-immunoprecipitation analyses showed that PACS-1 and PACS-2 associate with different vesicular coat complexes. While PACS-1 associated with both the AP-1 and AP-3 clathrin adaptors (Figure 5D; Crump et al, 2001), PACS-2 selectively associated with COPI; this association could be disrupted in the PACS-2admut construct, a mutant analogous to PACS-1admut. To identify which region of PACS-2 is required for the interaction with COPI, the 889 residues of PACS-2 were divided into four segments. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins corresponding to each of the four regions of PACS-2 were purified, and incubated with cell lysates (Figure 5E). Protein complexes were captured with glutathione-agarose and bound COPI was identified by Western blot. This analysis showed that the region of PACS corresponding to the PACS-1 cargo/adaptor-binding domain, GST-PACS37–179, bound directly to COPI. To test whether PACS-2 connects TRPP2 to COPI by forming a ternary complex, GST-PKD2S812D was incubated with purified COPI in the presence or absence of PACS37–179. GST capture showed an approximately three-fold greater amount of COPI associated with GST-PKD2S812D in the presence of PACS-2 than in its absence (Figure 5F). These data show that a ternary complex can form in vitro, and identify PACS-2 as a connector protein that can directly link acidic cluster motifs with COPI. They also demonstrate that PACS-2admut functions as a dn mutation, because of its abrogated COPI binding. We next used PACS-2admut to examine polycystin-2 localization after interference with PACS-2 and found that this mutant shifted polycystin-2 from the ER to the Golgi compartment (Figure 5G). Fluorescence polarization revealed that the furin-binding domain of PACS-1 and the homologous region of PACS-2 bound the acidic cluster of polycystin-2 with similar affinities, whereas the acidic cluster di-leucine-binding domain of GGA3 (Kato et al, 2002b) failed to interact with the phosphorylated polycystin-2 peptide (Figure 5H). However, neither dn PACS-1 nor dn PACS-2 alone resulted in the surface expression of a Tac-polycystin-2 fusion protein. Only the coexpression of both dn PACS proteins dramatically increased polycystin-2 surface expression (Figure 5I). Therefore, the trafficking and surface expression of polycystin-2 appears to be a two-step process directed by PACS-2 at the ER, and by PACS-1 at Golgi/TGN compartment of the secretory pathway. An interdependent role involving both PACS proteins was confirmed by RNA interference of PACS-1 and PACS-2 expression in Xenopus oocytes. siRNA directed against either xPACS-1 or xPACS-2 did not alter whole cell conductance (Figure 5J); only microinjection of both siRNAs generated a significant increase in whole cell currents in oocytes expressing WT polycystin-2 (Figure 5K).

Figure 5.

Trafficking and surface expression of polycystin-2 is controlled by PACS-1 and PACS-2. (A) The carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-2, fused to the sIg7 tag, precipitates HA-PACS-2 (full length) from transiently transfected HEK 293T cells. (B) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous polycystin-2 from COS M6 immobilizes native PACS-2. (C) Mutation of serine 812 to alanine (PKD2 S812A) or mutation of the acidic cluster (PKD2 D815-817A), but not the serine 812 to aspartic acid mutation abrogates the interaction between polycystin-2 and PACS-2. The interactions were tested using the carboxy-terminal domain of WT or mutant polycystin-2 fused to the sIg7 tag and the HA-tagged PACS-2 in transiently transfected HEK 293T cells. (D) Adaptor co-immunoprecipitations. HA-tagged PACS-1, PACS-2, PACS-1admut or PACS-2admut were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA. Co-immunoprecipitating AP-1, AP-3 and COPI were detected by Western blot analysis. (E) Domain mapping for the interaction of PACS-2 with COPI. COPI was pulled down from cellular lysates using GST-tagged fragments of PACS-2 (amino-acid residues are indicated) (control=GST, input=1% of initial lysate). (F) Ternary complex formed between recombinant COPI, PACS-2 and polycystin-2. Immobilized GST-PKD2741–871 S812D immobilized β-COP in the presence of PACS-237–179. (G) The Tac-polycystin-2 localizes to the ER. Interference with PACS-1 function by expression of a dn PACS-1 protein does not alter the subcellular distribution of polycystin-2, whereas expression of a dn PACS-2 protein allows polycystin-2 to exit the ER and translocate to the Golgi apparatus. (H) Affinities between polycystin-2 and PACS-1, PACS-2 or GGA3 were compared using fluorescent polarization. A fluorescein-tagged polycystin-2 phosphopeptide RSFPRSLDDpSEEDDDEDSGHSSRRR, derived from the putative PACS-binding site of polycystin-2, was incubated with different GST fusion proteins as indicated. The upper panel depicts the time-dependent interaction between the polycystin-2 peptide and the respective fusion proteins. In the lower panel. fluorescein-tagged polycystin-2 peptide (66 nM final concentration) was added to serially diluted GST fusion proteins to determine the dissociation constants (kD). (I) Surface labelling of nonpermeabilized cells expressing Tac-tagged polycystin-2. Neither dn PACS-1 nor dn PACS-2 alone increases the surface expression of polycystin-2 compared to control. In six randomly picked areas, only 1±1 cells were positive expressing polycystin-2 alone (n=4), 2±1 cells were positive coexpressing dn PACS-1 (n=2) and 4±2 cells were positive coexpressing dn PACS-2 (n=2). Coexpression of both dn PACS proteins dramatically increased the surface expression of polycystin-2 to 26±5 positive cells (n=4). (J) Injection of either xPACS-1 or xPACS-2 siRNA had no effect on the whole cell conductance of either water-injected oocytes (gray bars) or oocytes expressing polycystin-2 (black bars) (n=10). (K) Combined injection of xPACS-1 and xPACS-2 siRNA significantly increased the whole cell conductance of polycystin-2-expressing oocytes, whereas it had no effect on water-injected oocytes (gray bars: control siRNA; black bars: xPACS-1 and xPACS-2 siRNA) (n=10).

Phosphorylatable acidic clusters: a general mechanism of ion channel trafficking?

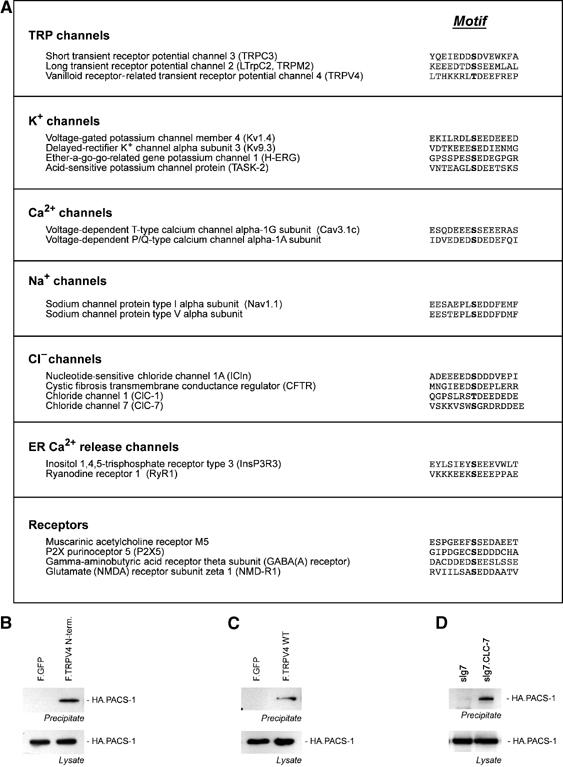

Our findings suggest that PACS family members participate in a novel mechanism for ER release and forward transport of ion channels with a phosphorylatable acidic cluster. A search of the NCBI database for proteins with phosphorylatable acidic clusters (D/ED/ED/ESD/ED/ED/E) revealed that many ion channels and membrane receptors contain potential PACS-binding motifs (Figure 6A). We tested several candidates for interaction with PACS molecules. The calcium-permeable, nonselective cation channel TRPV4 is a member of the TRP subfamily of temperature-sensitive ion channels (reviewed in Nilius et al, 2004). Although TRPV4 appears at the plasma membrane, a substantial fraction is retained in subcellular compartments (data not shown). TRPV4 interacts with PACS-1 (Figure 6B and C), as does the intracellular Cl− channel CLC-7 (reviewed in Jentsch et al, 2002). CLC-71–123 fused to an immunoglobulin tag (sIg7.CLC-7) co-precipitates HA-tagged PACS-1 (Figure 6D). Thus, PACS proteins may direct the localization of TRPV4, CLC-7 and other ion channels to distinct subcellular compartments.

Figure 6.

PACS interacts with acidic clusters of other ion channels. (A) Database search for ion channels with acidic clusters. (B) Flag-tagged TRPV41–486 and TRPV4 WT (C) interact with HA-tagged PACS-1. (D) CLC-71–123 fused to an immunoglobulin tag (sIg7.CLC-7) co-precipitates HA-tagged PACS-1.

Discussion

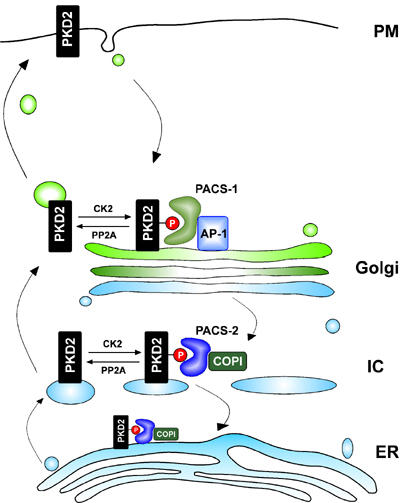

PACS molecules direct the subcellular localization of polycystin-2

PACS-1 is a cellular sorting protein that directs the endosome-to-Golgi trafficking of furin by connecting the acidic cluster-containing domain of furin to the AP-1 (reviewed in Thomas, 2002). Dominant negative mutations of PACS-1 that selectively disrupt the interaction with AP-1 cause mislocalization of furin from the TGN to endosomal compartments (Crump et al, 2001). Complementing the PACS-1-mediated endosome-to-Golgi retrieval of cargo proteins is the role of PACS-2 in Golgi-to-ER retrieval of cargo proteins. PACS-2 localizes to the ER (Simmen et al, 2005) and binds COPI, an adaptor that directs the retrieval of cargo protein from the Golgi to ER (reviewed in Murshid and Presley, 2004). The interaction between COPI and PACS-2 suggests that this protein complex regulates the retrieval of polycystin-2 from the Golgi to the ER (Figure 7). Newly synthesized polycystin-2 may immediately undergo phosphorylation to mark it for PACS-2-mediated retrieval to the ER compartment, as CK2 is conveniently associated with the ER (Faust et al, 2001), and most of the cellular polycystin-2 is phosphorylated on S812 in vivo (Cai et al, 2004). Following dephosphorylation of S812, polycystin-2 is routed to the TGN, where it is sorted for its final destination. Polycystin-2 traffics to the Golgi apparatus in the absence of PACS-2, but fails to accumulate at the plasma membrane (Figure 5), suggesting that PACS-1 directs the retrieval of polycystin-2 from endosomal compartments back to the TGN. Polycystin-2 escapes the PACS-mediated retrieval mechanism and accumulates at the plasma membrane only when both PACS molecules are absent or upon inhibition of CK2 activity. Thus, polycystin-2 trafficking is sequentially controlled at two different levels by PACS-2 and PACS-1, which direct Golgi-to-ER and endosome-to-TGN retrieval, respectively. These findings clearly resolve the hitherto puzzling opposition of polycystin-2 localizations: the ER retention of transiently expressed polycystin-2 (Cai et al, 1999; Koulen et al, 2002; Grimm et al, 2003) versus the presence of endogenous polycystin-2 at the plasma membrane of renal tubular cells (Foggensteiner et al, 2000; Newby et al, 2002; Scheffers et al, 2002; Luo et al, 2003). By regulating its interaction with PACS proteins, we could direct polycystin-2 to localize to ER or plasma membrane, a major advance in the understanding of polycystin-2 trafficking.

Figure 7.

Model of polycystin-2 trafficking. Polycystin-2 (PKD2), phosphorylated on serine 812 by CK2, binds to PACS-2/COPI and is retrieved from the intermediate compartment (IC) back to the endoplasmic compartment (ER). Dephosphorylation of polycystin-2 by PP2A releases polycystin-2 from this interaction, and facilitates its translocation to the plasma membrane. PACS-1/AP-1 mediates the retrieval of polycystin-2 to the Golgi/TGN compartment.

Regulation of PACS binding

The interaction of polycystin-2 with adaptor proteins PACS-1 and PACS-2 is regulated by the CK2-dependent phosphorylation of serine 812. Polycystin-1 binds polycystin-2 and reportedly facilitates the translocation of polycystin-2 to the plasma membrane (Hanaoka et al, 2000). Accordingly, we speculated that polycystin-1 shields the PACS-binding site of polycystin-2. However, neither full-length polycystin-1 nor the carboxy-terminal domain of polycystin-1 affected the interaction between polycystin-2 and PACS proteins (data not shown). Interaction between polycystin-2 and PACS proteins is curtailed by phosphorylation of serine 812 by CK2. The active CK2 holoenzyme is composed of two catalytic subunits (α and α′) and two regulatory subunits (β subunits). Although CK2 phosphorylates a large number of cellular proteins, the regulation of CK2 activity remains rather mysterious (reviewed in Litchfield, 2003). Whereas expression of the catalytic CK2 α subunit is inhibited by TGF-β1 (Cavin et al, 2003), the activity of CK2 is stimulated by INF-γ or src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation (Donella-Deana et al, 2003; Mead et al, 2003). Interestingly, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein, upregulated by some Wnt molecules (Papkoff et al, 1996), inhibits CK2 activity (Homma et al, 2002). During renal tubulogenesis, requisite Wnt signalling could modulate CK2 activity and polycystin-2 localization (Dressler, 2002). Alternatively, activation of PP2A could release polycystin-2 from its interaction with PACS molecules (Molloy et al, 1998) and promote localization of polycystin-2 to the plasma membrane. Coexpression of polycystin-1 did not affect the binding of PACS-1 to polycystin-2 at the plasma membrane; however, modulation of CK2 or PP2A may require ligand-mediated activation of polycystin-1.

PACS molecules interact with phosphorylatable acidic clusters of other ion channels

Important cellular functions are defined by the activity of ion channels, mandating complex mechanisms to control their trafficking to the cell surface. Many channels reside in the ER until homo- or heterodimeric interactions with other pore-forming or auxillary subunits permit their exit from the ER. These interactions shield retention signals, such as the RKR, RSRR, RXT motifs in KIR, GABAB receptor and CFTR, or they mask assembly motifs, such as the PL(Y/F)(F/Y)xxN motif in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel (reviewed in Deutsch, 2003). Other signals promote anterograde trafficking of ion channels such as the diacidic motifs present in KIR 1.1 and 2.1 channels (Ma et al, 2001). Recently, 14-3-3 was shown to release ion channels in a phosphorylation-dependent manner from the ER, providing insight into the regulation of forward trafficking of channels with a dibasic N-terminal β-COP-binding site (O'Kelly et al, 2002). Our database search for ion channels with acidic clusters detected this motif in many ion channels (Figure 6A). We demonstrated that even less perfect matches such as the partial acidic cluster of TRPV4, containing a threonine rather than a serine, mediate binding of PACS-1. The presence of candidate PACS-binding motifs within many ion channels suggests a broad and important role for PACS proteins in the sorting of ion channels, and thereby an important mechanism for controlling the activity of ion channels.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that PACS-1 and PACS-2 direct the localization of polycystin-2 and alter the permeability of the plasma membrane to cations such as calcium. The interaction between polycystin-2 and PACS proteins is mediated by a phosphorylatable acidic cluster within the carboxy-terminus of polycystin-2. Our findings clarify the molecular mechanisms that retain polycystin-2 in the ER and sort it to the plasma membrane. The presence of acidic cluster sorting motifs within the cytoplasmic domains of a large number of ion channels suggests that PACS proteins may play an important role in the trafficking of ion channels between secretory pathway compartments.

Materials and methods

Materials

Flag-tagged versions of polycystin-2 and point mutations were generated by PCR and standard cloning techniques. The PACS-1 constructs (Molloy et al, 1998; Crump et al, 2001) and polycystin-2 antiserum (Foggensteiner et al, 2000) have recently been described. The immunoglobulin tag contains the leader sequence of CD5 followed by the CH2 and CH3 domain of human immunoglobulin and the transmembrane region of CD7. The CD16.7 tag contains the extracellular domain of CD16, followed by the transmembrane region of CD7. Both tags have been previously described (Tsiokas et al, 1997). Recombinant proteins, fused to the MBP, GST or HIS tag, were generated as previously described (Kim et al, 1999). Tac-polycystin-2 fusion cDNAs were constructed as follows: a Sal1 site was inserted by PCR after the transmembrane sequence of human Tac/CD25 in pGEMT-Easy (Promega) with the oligos GCT CAC CTG GCA GCG TCG ACA GAG GAA GAG TAG and CTA CTC TTC CTC TGT CGA CGC TGC CAG GTG AGC. Another in-frame Sal1 site was generated by PCR at the beginning of the cytosolic tail sequence of human polycystin-2 with the oligo ATA TCG TCG ACA GGG CTA CCA TAA AGC TTT G and the fused cDNA was inserted into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). For the construction of dn PACS-2 with the oligos CCA GTG GAC AAG TGG CTG CAG CTG CGG CCG CTG CAG CTT CCT TGC AGT ATC CTC and GAG GAT ACT GCA AGG AAG CTG CAG CGG CCG CAG CTG CAG CCA CTT GTC CAC TGG, the amino acids 89–96 were PCR-mutated to alanines as previously described for dn PACS-1. Thioredoxin (TRX)-PACS-2 FBR sequence (residues 37–179) of human PACS-2 was expressed using pET32 (Novagen). GST fusion proteins containing the PACS-2 fragments corresponding to residues 1–36 (amino-terminal region), 37–179 (cargo/adaptor-binding region (FBR)), 37–1798A (FBR containing an E89TDLALTF → Ala8 substitution, 180–467) and 468–889 were generated by subcloning the respective DNA fragments into pGEX3X (Amersham). DRB was purchased from Alexis (Germany). TBB was kindly provided by LA Pinna (University of Padua), and subsequently synthesized. Briefly, a suspension of benzotriazole (1.00 g, 8.39 mmol) and sodium acetate (2.81 g, 34.2 mmol) in acetic acid (7 ml) was added to bromine (2.0 ml, 39 mmol). The reaction mixture was heated to 120°C in a sealed tube for 60 h, and poured into water (50 ml); the resulting precipitate was recrystallized from ethanol:water (1:1). The raw product was purified by repeated recrystallization from acetic acid to give pure TBB (158 mg) with a melting point of 261–263°C (Wiley and Hussung, 1957).

Co-immunoprecipitations

In vitro binding assays were performed as previously described (Crump et al, 2001). For the PACS-2-COPI binding assays, 8 × 106 A7 cells were lysed in mRIPA (1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, supplemented with protease inhibitors (COMPLETE, Roche)) and incubated with 25 μg of PACS-2-GST fragments followed by streptavidin-agarose pull-down and Western blot with anti-β-COP. To detect PKD2–PACS-2–COPI ternary complex formation, 10 μg of GST or GST-calnexin fusion proteins was preincubated with glutathione-agarose, and then mixed with 30 μg of Trx-PACS-2FBR or 2 μg of purified COPI, or both in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 25 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgOAc, 0.1 mM DTT, protease inhibitors and 5 mg/ml BSA. The bound material was analyzed by Western blot with anti β-COP. Western blot analysis and co-immunoprecipitations were performed as recently described (Kim et al, 1999; Benzing et al, 2001), and representative results of at least three independent experiments are shown.

Immunofluorescence

To determine the subcellular localization of CD16.7-PKD2 chimeras, transiently transfected COS M6 cells were fixed with acetone/methanol and incubated with the primary antibody as indicated, followed by the appropriate fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody. Images were obtained using a confocal microscope (LSM 510; Zeiss, Jena, Germany). To determine the surface expression of proteins, transiently transfected COS M6 cells were detached in 0.5 mM EDTA/PBS and labelled with primary and secondary antibodies at 4°C. Cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde/PBS and analyzed by FACS. To determine the subcellular localization of Tac-PKD2 chimeras, BSC40 cells were plated at 100 000 in 35-mm dishes, and transfected the subsequent day with pcDNA3-Tac-PKD2 chimera using GENEporter (GTS) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. After 24 h, the cells were infected with adenovirus expressing either the trans activator alone or in combination with PACS-1admut, PACS-2admut or both (m.o.i.: 20). At 24 h after infection, cells were processed for immunofluorescence. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed in formaldehyde/PBS and permeabilized in blocking buffer (0.5 Triton X-100, 0.2% goat serum in PBS). Staining was performed with anti-mannosidase II from K Moremen (1:1000) and anti-2A3A1HTac antibody (1:400). Antibodies were visualized using Alexa antibodies (goat anti-IgG1 594 for 2A3AH1 and anti-rabbit 488 for mannosidase). Images were captured using × 63 oil immersion objective on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. For external binding, cells were incubated for another hour at 4°C in growth medium containing anti-2A3A1H (1:400) and then fixed. Bound antibody was revealed using Alexa goat anti-IgG1 594 antibody. There was no permeabilization step; Triton X-100 was omitted from the blocking buffer.

Electrophysiology

Oocytes were isolated by partial ovarectomy from X. laevis. cRNAs were synthesized in vitro using the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion). At 12–24 h after isolation, stage V–VI oocytes were injected with 30 nl of water containing 10 ng cRNA of WT polcystin-2 or various mutations of polycystin-2. Voltage clamp experiments were performed at 3–6 days after injection of cRNAs. Whole cell currents of oocytes were recorded using the Turbo TEC 03X voltage/current clamp amplifier (npi electronic, Tamm, Germany) and 2 M KCl microelectrodes with resistances of 0.5–2 MΩ. All whole cell voltage clamp experiments were performed at 20°C in ND96 solution (composition (in mM): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES). Equimolar substitution of Cl− by gluconate and Na+ by N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG) was carried out as indicated. Oocytes were clamped at 0 mV, and voltage ramps from −100 to +50 mV were applied every 1.2 s. Conductance was determined in the negative voltage range (−100 to 0 mV). Data are presented as original recordings or as mean±s.e.m. (n=number of experiments). Unpaired and paired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was accepted to indicate statistical significance. The experiments were performed with five different batches of oocytes.

Fluorescence polarization

To determine the affinities between polycystin-2 and PACS-1, PACS-2 and GGA3, we performed fluorescence polarization assays as described previously (Benzing et al, 2000). Briefly, GST fusion proteins were expressed in bacteria and purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads (GST.PACS-185–280, GST.PACS-2117–266 and GST.GGA31–146). The fluorescent polycystin-2 phosphopeptide was linked with FITC to the peptide amino-terminus via a β-alanine linker (Jerini AG, Berlin, Germany). Fluorescence polarization anisotropy was measured using a Panvera Beacon 2000. Fluorescein-tagged peptide was mixed in (66 nM final concentration) and fluorescence polarization measured at 22°C after a 120-s delay. GST fusion proteins were serially diluted to measure the binding curves.

RNA interference

To silence gene expression of xPACS-1 or xPACS-2, synthetic siRNA was injected into Xenopus oocytes 3–4 days prior to voltage clamp experiments. The siRNA target sequences were AACTTCAGGGCTCAAAACGT and AATAACCGGCAACAGAACTT for xPACS-1 and xPACS-2, respectively (based on Xenopus sequences BI444377 and BG360195).

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Engel, Stefanie Keller, Roland Nitschke, Birgit Schilling and Bettina Wehrle for expert technical assistance, and Thomas Jentsch, Rainer Duden and Veit Flockerzi for the kind gift of reagents. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG BE 2212 and DFG WA597), NIH grants DK37274, AI48585 and AI49793 (GT), and a grant of the Thyssen Foundation (GW).

References

- Benzing T, Gerke P, Hopker K, Hildebrandt F, Kim E, Walz G (2001) Nephrocystin interacts with Pyk2, p130(Cas), and tensin and triggers phosphorylation of Pyk2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 9784–9789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzing T, Yaffe MB, Arnould T, Sellin L, Schermer B, Schilling B, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K, Leparc GG, Kim E, Walz G (2000) 14-3-3 interacts with regulator of G protein signaling proteins and modulates their activity. J Biol Chem 275: 28167–28172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand CA, Frizzell RA (2003) The role of regulated CFTR trafficking in epithelial secretion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C1–C18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Anyatonwu G, Okuhara D, Lee KB, Yu Z, Onoe T, Mei CL, Qian Q, Geng L, Wiztgall R, Ehrlich BE, Somlo S (2004) Calcium dependence of polycystin-2 channel activity is modulated by phosphorylation at ser812. J Biol Chem 279: 19987–19995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Maeda Y, Cedzich A, Torres VE, Wu G, Hayashi T, Mochizuki T, Park JH, Witzgall R, Somlo S (1999) Identification and characterization of polycystin-2, the PKD2 gene product. J Biol Chem 274: 28557–28565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavin LG, Romieu-Mourez R, Panta GR, Sun J, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS, Sonenshein GE, Arsura M (2003) Inhibition of CK2 activity by TGF-beta1 promotes IkappaB-alpha protein stabilization and apoptosis of immortalized hepatocytes. Hepatology 38: 1540–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XZ, Segal Y, Basora N, Guo L, Peng JB, Babakhanlou H, Vassilev PM, Brown EM, Hediger MA, Zhou J (2001) Transport function of the naturally occurring pathogenic polycystin-2 mutant, R742X. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 282: 1251–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O'Riordan CR, Smith AE (1990) Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell 63: 827–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE (2003) TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature 426: 517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump CM, Xiang Y, Thomas L, Gu F, Austin C, Tooze SA, Thomas G (2001) PACS-1 binding to adaptors is required for acidic cluster motif- mediated protein traffic. EMBO J 20: 2191–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch C (2003) The birth of a channel. Neuron 40: 265–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donella-Deana A, Cesaro L, Sarno S, Ruzzene M, Brunati AM, Marin O, Vilk G, Doherty-Kirby A, Lajoie G, Litchfield DW, Pinna LA (2003) Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase CK2 by Src-related tyrosine kinases correlates with increased catalytic activity. Biochem J 372: 841–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler G (2002) Tubulogenesis in the developing mammalian kidney. Trends Cell Biol 12: 390–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust M, Jung M, Gunther J, Zimmermann R, Montenarh M (2001) Localization of individual subunits of protein kinase CK2 to the endoplasmic reticulum and to the Golgi apparatus. Mol Cell Biochem 227: 73–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foggensteiner L, Bevan AP, Thomas R, Coleman N, Boulter C, Bradley J, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Klinger K, Sandford R (2000) Cellular and subcellular distribution of polycystin-2, the protein product of the PKD2 gene. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 814–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perrett S, Kim K, Ibarra C, Damiano AE, Zotta E, Batelli M, Harris PC, Reisin IL, Arnaout MA, Cantiello HF (2001) Polycystin-2, the protein mutated in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), is a Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 1182–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm DH, Cai Y, Chauvet V, Rajendran V, Zeltner R, Geng L, Avner ED, Sweeney W, Somlo S, Caplan MJ (2003) Polycystin-1 distribution is modulated by polycystin-2 expression in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 278: 36786–36793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu F, Crump CM, Thomas G (2001) Trans-Golgi network sorting. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 1067–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka K, Qian F, Boletta A, Bhunia AK, Piontek K, Tsiokas L, Sukhatme VP, Guggino WB, Germino GG (2000) Co-assembly of polycystin-1 and -2 produces unique cation-permeable currents. Nature 408: 990–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert SC (2003) Bartter syndrome. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12: 527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma MK, Li D, Krebs EG, Yuasa Y, Homma Y (2002) Association and regulation of casein kinase 2 activity by adenomatous polyposis coli protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 5959–5964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F, Zdebik AA (2002) Molecular structure and physiological function of chloride channels. Physiol Rev 82: 503–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BG, Thomas L, Molloy SS, Thulin CD, Fry MD, Walsh KA, Thomas G (1995) Intracellular trafficking of furin is modulated by the phosphorylation state of a casein kinase II site in its cytoplasmic tail. EMBO J 14: 5869–5883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Misra S, Puertollano R, Hurley JH, Bonifacino JS (2002a) Phosphoregulation of sorting signal–VHS domain interactions by a direct electrostatic mechanism. Nat Struct Biol 9: 532–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Saurav M, Puertollano R, Hurley JH, Bonifacino JS (2002b) Phosphoregulation of sorting signal–VHS domain interactions by a direct electrostatic mechanism. Nat Struct Biol 9: 532–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Arnould T, Sellin L, Benzing T, Comella N, Kocher O, Tsiokas L, Sukhatme V, Walz G (1999) Interaction between RGS7 and polycystin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6371–6376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P, Cai Y, Geng L, Maeda Y, Nishimura S, Witzgall R, Ehrlich BE, Somlo S (2002) Polycystin-2 is an intracellular calcium release channel. Nat Cell Biol 4: 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield DW (2003) Protein kinase CK2: structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem J 369: 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Vassilev PM, Li X, Kawanabe Y, Zhou J (2003) Native polycystin 2 functions as a plasma membrane Ca2+-permeable cation channel in renal epithelia. Mol Cell Biol 23: 2600–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Jan LY (2002) ER transport signals and trafficking of potassium channels and receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol 12: 287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Zerangue N, Lin YF, Collins A, Yu M, Jan YN, Jan LY (2001) Role of ER export signals in controlling surface potassium channel numbers. Science 291: 316–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead JR, Hughes TR, Irvine SA, Singh NN, Ramji DP (2003) Interferon-gamma stimulates the expression of the inducible cAMP early repressor in macrophages through the activation of casein kinase 2. A potentially novel pathway for interferon-gamma-mediated inhibition of gene transcription. J Biol Chem 278: 17741–17751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy SS, Thomas L, Kamibayashi C, Mumby MC, Thomas G (1998) Regulation of endosome sorting by a specific PP2A isoform. J Cell Biol 142: 1399–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy SS, Thomas L, VanSlyke JK, Stenberg PE, Thomas G (1994) Intracellular trafficking and activation of the furin proprotein convertase: localization to the TGN and recycling from the cell surface. EMBO J 13: 18–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C (2001) Physiology, phylogeny, and functions of the TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE 2001: RE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshid A, Presley JF (2004) ER-to-Golgi transport and cytoskeletal interactions in animal cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 61: 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev PM, Li X, Elia AEH, Lu W, Brown EM, Quinn SJ, Ingber DE, Zhou J (2003) Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet 33: 129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby LJ, Streets AJ, Zhao Y, Harris PC, Ward CJ, Ong AC (2002) Identification, characterization, and localization of a novel kidney polycystin-1–polycystin-2 complex. J Biol Chem 277: 20763–20773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Vriens J, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T (2004) TRPV4 calcium entry channel: a paradigm for gating diversity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C195–C205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kelly I, Butler MH, Zilberberg N, Goldstein SA (2002) Forward transport. 14-3-3 binding overcomes retention in endoplasmic reticulum by dibasic signals. Cell 111: 577–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papkoff J, Rubinfeld B, Schryver B, Polakis P (1996) Wnt-1 regulates free pools of catenins and stabilizes APC–catenin complexes. Mol Cell Biol 16: 2128–2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour GJ, San Agustin JT, Follit JA, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB (2002) Polycystin-2 localizes to kidney cilia and the ciliary level is elevated in orpk mice with polycystic kidney disease. Curr Biol 12: R378–R380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffers MS, Le H, van der Bent P, Leonhard W, Prins F, Spruit L, Breuning MH, de Heer E, Peters DJ (2002) Distinct subcellular expression of endogenous polycystin-2 in the plasma membrane and Golgi apparatus of MDCK cells. Hum Mol Genet 11: 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmen T, Aslan JE, Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Thomas L, Wan L, Xiang Y, Feliciangeli SF, Hung C-H, Crump CM, Thomas G (2005) PACS-2 controls endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria communication and Bid-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J [E-pub ahead of print: 3rd February 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600559] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub O, Gautschi I, Ishikawa T, Breitschopf K, Ciechanover A, Schild L, Rotin D (1997) Regulation of stability and function of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) by ubiquitination. EMBO J 16: 6325–6336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekirian TL (2002) The central role of the trans-Golgi network as a gateway of the early secretory pathway: physiologic vs nonphysiologic protein transit. Exp Cell Res 281: 9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Kiehn J, Katus HA, Karle CA (2003) Defective protein trafficking in hERG-associated hereditary long QT syndrome (LQT2): molecular mechanisms and restoration of intracellular protein processing. Cardiovasc Res 60: 235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G (2002) Furin at the cutting edge: from protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 753–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiokas L, Kim E, Arnould T, Sukhatme VP, Walz G (1997) Homo- and heterodimeric interactions between the gene products of PKD1 and PKD2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 6965–6970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan L, Molloy SS, Thomas L, Liu G, Xiang Y, Rybak SL, Thomas G (1998) PACS-1 defines a novel gene family of cytosolic sorting proteins required for trans-Golgi network localization. Cell 94: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick T, Germino G (2003) From cilia to cyst. Nat Genet 34: 355–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley RH, Hussung KF (1957) Halogenated benzotraizoles. J Am Chem Soc 79: 4395–4400 [Google Scholar]

- Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM (2002) The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2508–2516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandomeni R, Zandomeni MC, Shugar D, Weinmann R (1986) Casein kinase type II is involved in the inhibition by 5,6-dichloro-1-beta-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole of specific RNA polymerase II transcription. J Biol Chem 261: 3414–3419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]