Abstract

Although experiencing childhood sexual abuse (CSA) puts youth at risk for involvement in relationship violence, research is limited on the potential pathways from CSA to subsequent dating aggression. The current study examined prospective pathways from externalizing behavior problems and stigmatization (abuse-specific shame and self-blame attributions) to anger and dating aggression. One hundred sixty youth (73% female, 69% ethnic/racial minorities) with confirmed CSA histories were interviewed at the time of abuse discovery (T1, when they were 8–15 years of age), and again 1 and 6 years later (T2 and T3). Externalizing behavior and abuse-specific stigmatization were assessed at T1 and T2. Anger and dating aggression were assessed at T3. The structural equation model findings supported the proposed relations from stigmatization following the abuse to subsequent dating aggression through anger. Only externalizing behavior at T1 was related to later dating aggression, and externalizing was not related to subsequent anger. This longitudinal research suggests that clinical interventions for victims of CSA be sensitive to the different pathways by which youth come to experience destructive conflict behavior in their romantic relationships.

Constructive strategies for handling disagreements are necessary skills for healthy romantic relationships (Simon, Kobielski, & Martin, 2008). Strategies used to manage conflict are telling indicators of relationship functioning. The use of aggressive strategies in response to conflict is deleterious for individual and relationship health (Gallaty & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2008; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2008). Unfortunately, such strategies characterize a significant minority of adolescent relationships (Williams et al., 2008). Individuals with a history of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) are at increased risk for being involved in relationship violence (Banyard, Arnold, & Smith, 2000; DiLillo, Giuffre, Tremblay, & Peterson, 2001; White & Widom, 2003; Wolfe, Wekerele, Reitzel-Jaffe, & Lefebvre, 1998; Wolfe, Wekerele, Scott, Straatman, & Grasley, 2004). Despite empirical support for an association between CSA and dating aggression, there is limited prospective research on mechanisms through which these phenomena are related. This article focuses on individual differences in the development of dating aggression in youth with confirmed histories of CSA. Specifically, we examined potential processes that could explain associations between CSA and subsequent involvement in dating aggression in a sample first seen at the time of abuse discovery (T1—-when the abuse was reported to appropriate authorities) and followed 1 year (T2) and 6 years later (T3). We examined perpetration and victimization because adolescent relationship aggression is predominantly bidirectional (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997; Williams et al., 2008).

Individual differences studies that assess youths’ adaptation to CSA over time can provide insights into factors that explain the development of dating aggression. Using a within-group design, we examined how functioning following CSA was related to the subsequent use of aggressive strategies for dealing with romantic relationship conflict. Indicators of abuse severity, such as penetration and the use of force, are related to a greater likelihood of poor relationship outcomes (Arata, 2000; West, Williams, & Siegel, 2000). However, such associations tend to be weak and inconsistent, offering limited potential for understanding involvement in dating aggression or targets for intervention (Godbout, Sabourin, & Lussier, 2009). In contrast, previous work suggests that studying externalizing behavior, stigmatization, and anger may deepen our understanding of how individuals’ evaluation of and reaction to their CSA experiences are related to dating aggression (J. A. Andrews, Foster, Capaldi, & Hops, 2000; Bennett, Sullivan, & Lewis, 2005; Feiring, Simon, & Cleland, 2009; Kim, Talbot, & Cicchetti, 2009).

One pathway by which CSA could potentiate dating aggression is through its association with externalizing behavior problems. The controlling and aggressive behavior that children with CSA histories experience from perpetrators may engender externalizing behavior problems, including aggression toward family and peers (Cosentino, Meyer-Bahlburg, Albert, & Gaines, 1993; Swanston, Parkinson, O’Toole, Plunkett, Shrimpton, & Oates, 2003). Social learning theory predicts that antisocial behavior with parents and peers is likely to carry over to other interpersonal contexts (Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004; Shortt, Capaldi, Dishion, Bank, & Owen, 2003). Furthermore, findings from prospective developmental studies show that externalizing behavior problems in childhood or adolescence significantly predict later aggression toward a partner (J. A. Andrews et al., 2000; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2002). Biased social information processing appears to be a significant mediator of this developmental pathway (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge & Pettit, 2003). Specifically, youth with externalizing behavior problems are inclined to interpret actual or ambiguous relational slights as hostile and to become angry. Dysregulated angry emotions increase the likelihood that youth with externalizing problems, including those with CSA histories, will react abusively toward romantic partners in conflict situations (Holtzworth-Munroe, Bates, Smutzler, & Sandin, 1997; Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004; Lochman, Barry, & Pardini, 2003; Nichols, Graber, Brooks-Gunn, & Botvin, 2006; Wolfe et al., 2004). The current study builds upon these studies to examine prospective associations between earlier externalizing behavior in children with a CSA history and subsequent tendencies toward anger and dating aggression.

Whereas externalizing problems may predict anger and dating aggression for youth with and without CSA histories, other pathways may be abuse specific. Defined in terms of abuse-specific shame and self-blame, stigmatization often occurs in CSA victims and can continue once the abuse and its discovery have ended (Feiring & Cleland, 2007; Feiring & Taska, 2005). Self-blame attributions are believed to be necessary for the self-evaluative emotion of shame, and each are among the most negative types of self-appraisals (Lewis, 1992; Platt & Freyd, 2011). Abuse-specific stigmatization is a process that is likely to disrupt the development of interpersonal problem-solving and conflict resolution skills (Feiring, Rosenthal, & Taska, 2000; Feiring et al., 2009; Finkelhor & Browne, 1985; Kim et al., 2009). Shame is associated with being submissive, feeling devalued, and the desire to retaliate against a partner seen as the source of humiliation (Covert, Tangney, Maddux, & Heleno, 2003; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Individuals with a self-blaming attribution style are likely to believe they deserve hostile and aggressive acts from their partners. This style is related to dissatisfaction with close relationships, poor relationship quality, and risky relationship behavior (Feiring et al., 2000; Fletcher, Fitness, & Blampied, 1990; Liem & Boudewyn, 1999). Two studies directly examined the relation between stigmatization and dating aggression. In a cross-sectional study, women with self-reported histories of CSA were more likely to report being involved in aggressive interactions with their partners, and this association was mediated by shame experienced in everyday contexts (Kim et al., 2009). Work from the sample used in this study showed that there were concurrent simple correlations between abuse-specific stigmatization and perpetrating and being the victim of dating aggression, but prospective associations between earlier stigmatization and aggression were absent (Feiring, Simon, & Cleland, 2009). Such results led us to consider the possibility that earlier stigmatization might be related to involvement in dating aggression indirectly through anger.

Theorists and clinicians suggest that because shame and self-blame strongly interfere with the human motive to feel good about the self, they may be converted into less threatening emotions and thoughts. In particular, through a cognitive reappraisal of events in terms of other- rather than self-blame, individuals may shift from self-directed shame to other-directed anger and hostility (Lewis, 1992; Scheff, 1987; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Individuals who are prone to stigmatization may try to alter this intensely negative state by displacing it with anger, and such anger increases the likelihood that aggressive rather than constructive approaches to conflict will be enacted (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). In nonabused samples, there is evidence for an association between stigmatization and anger. Cross-sectional research shows that individuals who report being higher in stigmatization have difficulty accurately interpreting social cues. They show an increased tendency to perceive others as hostile and angry and are more likely to anticipate that they will respond to others with anger (J. A. Andrews et al., 2000; Harper & Arias, 2004; Tangney, Wagner, Fletcher, & Gramzow, 1992; Tangney, Wagner, Hill-Barlow, Marschall, & Gramzow, 1996). One diary study had middle school students rate their own experiences with shame events and nominate classmates who were angry or furious daily for 10 days (Thomaes, Stegge, Olthof, Bushman, & Nezlek, 2011). Results indicated that students were more likely to be nominated by their peers as angry on days when they reported experiencing a shameful event. We could find only one study that examined the link between maltreatment and anger as mediated by shame (Bennett et al., 2005). Preschoolers with and without child welfare reports of maltreatment were observed in experimental success and failure tasks designed to elicit shame and anger; these emotions were reliably coded from videotapes of the procedure. Children with more allegations of physical abuse were more likely to show shame, and more shame was related to more anger. There was a trend for shame to mediate the relation between abuse and anger. Research also supports the idea that stigmatization increases the likelihood that anger will result in aggression rather than be managed in more constructive ways (Tangney et al., 1996). Adolescents and young adults who were prone to shame compared to guilt reported experiencing more anger in interpersonal situations and expected to be more physically and verbally aggressive when angered. Although research, for the most part on nonabused samples using cross-sectional designs, supports the different potential links from maltreatment to stigmatization, stigmatization to anger, and anger to aggression, we could find no study that directly examined this conceptualization. This study was a first step in addressing the dearth of research on the stigmatization to anger pathway to dating aggression among youth with a CSA history.

PREDICTIVE MODEL

Using longitudinal data, this study examined a model in which externalizing behavior and stigmatization were expected to be related to subsequent anger and involvement in dating aggression in individuals with a CSA history. We anticipated five direct relations among abuse severity, externalizing behavior, stigmatization, anger, and dating aggression that did not consider intervening processes. First, greater abuse severity was expected to be related to more externalizing behavior and stigmatization at T1. Past this time of discovery, severity of abuse was not expected to be related to subsequent functioning because externalizing behavior and stigmatization would more directly index the consequences of the trauma (Feiring, Taska, & Chen, 2002). Second, higher levels of externalizing behavior and stigmatization at T1 were predicted to be related to higher levels of these variables at T2. Third, higher levels of externalizing behavior and stigmatization at T2 were predicted to be related to more anger at T3. Fourth, research on the consistency of externalizing behavior in different peer contexts suggested that earlier externalizing behavior would be related to subsequent involvement in dating aggression. However, our previous findings indicated that stigmatization would not be related to later dating aggression without considering intervening anger. Finally, we expected that more T3 anger would heighten the likelihood that the partner’s behavior would be perceived as hostile and thus be associated with dating aggression at T3.

We also expected two types of mediated effects. The first examined whether externalizing and stigmatization at T2 mediated the relation between these factors at T1 and anger at T3. Because externalizing behavior and stigmatization at T1 were the most temporally distant from the outcome at T3 (6 years), we expected that their association with T3 outcomes would be diluted by intervening processes (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). More specifically, we anticipated that the relations of these earliest T1 variables to T3 outcomes would operate through their association with externalizing behavior and stigmatization at T2. Because elevated levels of psychological distress are common in the immediate aftermath of abuse discovery, abuse reactions at this time may be relatively weak indicators of individual differences in long-term adjustment (Feiring et al., 2002; Ligezinska et al., 1996). We also expected that T3 anger would mediate the relation between externalizing and stigmatization at T2 and dating aggression at T3. We anticipated that the abuse-specific pathways involving stigmatization would contribute to our understanding of which CSA youth were more likely to report anger and dating aggression beyond the externalizing behavior pathways to aggression characteristic of youth with and without such histories.

METHOD

Sample Selection and Characteristics

The participants were recruited from urban and suburban populations in New Jersey. The sexual abuse was confirmed by at least one of the following criteria: specific medical findings, confession by the offender, abuse validated by an expert such as child protective services (CPS), or conviction of the offender in family or criminal court. The majority of the sample (95%) came directly from CPS offices or regional child abuse medical clinics working with CPS (Feiring, Taska, & Lewis, 1998). Children between the ages of 8 and 15 years of age who had been brought to the attention of authorities for sexual abuse within the past 8 weeks were approached to participate in the study. Intake logs were reviewed by project staff to identify eligible cases. The caseworkers then approached the families to obtain permission for project staff to contact them to discuss the study. Of the 180 families contacted by the project staff, 160 agreed to participate in the study. The recruited sample of children and their families were assessed at abuse discovery (T1) before they received treatment, and 147 were seen 1 year later (T2, M = 1.2 years, SD = .3 years). Attrition from T1 to T2 was due to families declining to participate (n = 10) and failure to locate families (n = 3). The third assessment was obtained approximately 6 years following abuse discovery on 121 of the original participants (T3, M = 6.2 years, SD = 1.2). Attrition from T2 to T3 was due to failure to locate participants (n = 13), active refusal (n = 7; participants informing us they did not want to complete the third assessment), and passive refusal (n = 6; participants failing to show up for appointments on multiple occasions but not willing to say they did not want to participate).

At T1, 55% of the sample were children (ages 8–11 years; M = 9.6, SD =1.1) and 45% were adolescents (ages 12–15 years; M = 13.5, SD =1.1). Female participants comprised 73% of the sample. The majority of participants came from single-parent families (67%) and were poor (64%, with an income of $25,000 or less). The ethnicity of the sample was self-reported as African American (41%), White (31%), Hispanic (20%), and other (8% including Native American and Asian). Based on the most serious form of contact abuse reported by this sample, 66% experienced genital penetration (31% experienced fondling or attempted penetration, and 3% were forced to watch the perpetrator masturbate). Almost all of the perpetrators were known to their victims, with 35% a parent figure, 26% a relative, 36% a familiar person who was not a relative, and 3% a stranger. Forty-three percent of the participants lived with the perpetrator at the time of the abuse. Frequency of the reported abusive events was once for 32% of the sample, two to nine times for 38%, and 10 times or more for 30%. The abuse lasted for 1 year or longer in 39% of the sample. The use of physical force was reported in 25% of the sample, the threat of force was reported in 20%, and in 55% of the cases no force or threat were reported.

After the initial and before the second assessment, the majority of participants received some form of intervention, typically from community-based agencies (68%; length of treatment M = 5.4 months, SD = 4.7 months); a minority of participants received intervention between the second and third assessments (39%; length of treatment M = 8 months, SD = 8.5 months). Participants in this study were not enrolled in a systematic treatment program, and we did not have control over who received treatment, the type of treatment received, or the expertise of the treatment providers. It therefore was not possible to reliably assess or understand how such varied interventions were related to our predictions.

Procedures

All of the procedures for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the academic institutions where the research took place. At each of the three assessment points, when the participant was a minor, informed assent was obtained from the child and informed consent from their parent/guardian. At T3, those participants who were 18 or older provided informed consent. The participants were administered a structured interview by a trained clinician in a private office. Abuse-related information was obtained from CPS and law enforcement case records at T1 after the children were interviewed. The participants were reimbursed a total of $250 for completion of the initial and the two follow-up assessments.

Measures

Abuse severity

To obtain information on specific characteristics of the abuse incidents that qualified the participant for inclusion in the study, trained staff members copied information from law enforcement agencies and CPS records to a checklist. The checklist recorded information on the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim, frequency (number of events reported) and duration (dates began and ended) of the victimization, how the abuse was discovered, the types of abusive acts experienced (e.g., fondling, penetration), the use of physical force, medical findings, and how the case was confirmed. Based on the records of 20 participants, two staff members copied information from the same case files onto the checklist with 100% or nearly 100% accuracy for each category of information. Coding of abuse information from the checklist (e.g., identity of the perpetrator as a stranger = 1, familiar person = 2, relative = 3, parent figure = 4) was completed by trained project personnel, among whom acceptable interrater reliability was obtained (κ = .73–1.0). A summary abuse severity index was calculated based on abuse characteristics that are related to poor outcomes and that are rated by professionals as being of greater severity (Chaffin, Wherry, Newlin, Crutchfield, & Dykman, 1997). For each youth an abuse severity score was obtained by summing over the most severe level of each of six abuse characteristics as follows: penetration, parent figure perpetrator, perpetrator living with the child at the time of abuse, 10 or more abuse events, duration of abuse for 1 year or longer, and use of physical force.

Externalizing behavior problems

At T1 and T2, ratings of externalizing problems were obtained from primary caregivers and teachers using parallel forms (caregivers: Child Behavior Checklist; teachers: Teacher Report Form; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). These standardized measures share items in common and have well-established reliability and validity. The Externalizing Behavior Score is derived from the Delinquent (e.g., cheating, swearing, and stealing) and Aggressive (e.g., being cruel, bullying and mean to others, and getting into many fights) syndrome scales. Reporters indicated whether each item relevant to these scales was ‘‘not true,’’ ‘‘somewhat true,’’ or ‘‘very true’’ about the child’s behavior. The internal consistency of the externalizing score for this sample was very good (parent: T1 α = .93, T2 α = .89; teacher: T1 α = .89, T2 α = .91). Items were summed to obtain a standardized T score based on gender and age. For each time point, the two caregiver and teacher externalizing T scores were averaged to create overall externalizing behavior scores for T1 and T2. When a participant was missing one reporter’s score, the score for the extant reporter was used.

Stigmatization processes

Abuse-related shame at T1 and T2 was assessed using four items developed for this study, for example, ‘‘I feel ashamed because I think that people can tell from looking at me what happened’’ and ‘‘When I think about what happened I want to go away by myself and hide.’’ The items were rated on a 3-point scale ranging 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true), and 2 (very true), with a higher score indicating greater abuse-related shame (α = 0.85 at T1 and T2; potential range is 0–8).

At T1 and T2, abuse-specific self-blame attributions were obtained using the Attribution about Abuse Inventory (see Feiring, Taska, & Chen, 2002, for a detailed account of how this measure was developed). Participants used a 3-point scale to rate the extent to which nine causal statements were true for why the abuse happened, ranging 2 (very true), 1 (somewhat true), and 0 (not true). For example, two items reads: This happened to me because ‘‘I was not smart enough to stop it from happening’’; and ‘‘I was not careful enough on those days.’’ A sum score from the nine items was derived with higher scores indicating more self-blame. This measure evidenced moderate internal consistency (T1 α = .75, T2 α = .75).

A summary stigmatization score was created to reduce the probability of Type I error and to reduce the number of predictors in the planned analyses given the relatively small sample size. A principal components analysis done separately on the T1 and T2 abuse-specific shame and self-blame scores showed that 74% and 75% of the variance was accounted for by one factor derived from the T1 and T2 scores, respectively. These results provided justification for combining the shame and self-blame scores within each time point to create a stigmatization score; the higher the score the more stigmatization reported.

Anger

Experiences of anger were obtained only at T3 using the anger/irritability scale from Trauma Symptom Inventory (Briere, 1995; Briere, Elliott, Harris, & Cottman, 1995). This scale is primarily focused on feelings of anger rather than aggressive behaviors. The participants were asked to rate how often in the last 6 months they had experienced anger using nine items that tapped into behaviors such as getting angry without knowing the reason and feeling mad and angry inside. The items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (often). The items were summed such that the higher scores indicated more anger. The internal consistency of the anger scale for this sample was very good (α = .89).

Dating aggression

The measures of dating aggression were obtained only at T3. Dating aggression was measured by the Conflict in Relationships Questionnaire (CIRQ; Wolfe et al., 2001). Developed for use with adolescents, this measure showed good test–retest reliability and structural and construct validity. This CIRQ was computer administered, with responses entered directly into the computer. The interviewer was not present during this part of the assessment (although she was available in an adjacent room if questions arose). This method of administration emphasized the confidentiality of the assessment and has been shown to promote willingness to report sensitive information to a greater extent than face-to-face interviews (Turner et al., 1998). Unfortunately, for seven participants the computer froze during this part of the assessment and their data were lost for this measure. Two participants who were 8 years old at T1 did not have relationship experience and therefore did not complete the CIRQ. Because these participants were old enough to have had romantic relationships at T3, they were retained in the analyses and their CIRQ scores were set at zero.

Youth with relationship experience completed items on dating aggression in reference to the frequency of their own behavior and that of their current (69%) or most recent partner using a 4-point scale, ranging 0 (never), 1 (seldom), 2 (sometimes), and 3 (often). Items used in this study indexed being the perpetrator and victim of physical aggression (four items, e.g., ‘‘I pushed, shoved, or shook my partner’’), threatening behavior (four items, e.g., ‘‘I threatened to hurt my partner’’), relational aggression (five items, e.g., ‘‘I spread rumors about my partner’’), and verbal aggression (nine items, e.g., ‘‘I insulted my partner with put-downs’’). Items for each type of aggression were summed with higher scores indicating more frequent aggression. To reduce the probability of Type I error, summary perpetration and victimization scores were created by adding the scores for each type of dating aggression. The higher the summary scores the more perpetration and victimization the participant reported. The rationale for these summary scores was based on the results of a principal components analysis done separately on Perpetration and Victimization subscale scores for the four types of aggression. All of the Perpetration subscale scores loaded on one factor that accounted for 69% of the variance, and all the Victimization subscale scores loaded on one factor that accounted for 73% of the variance. The alpha coefficients for these summary measures were acceptable (perpetration α = .76; victimization α = .75). Both the perpetration and victimization measures were positively skewed (1.67 and 2.36, respectively). Each was transformed by taking the natural logarithm after adding a constant of one. The transformation reduced the skew of each measure (−.61 and −.54, respectively).

Missing Data

Missing data were handled by the full information maximum likelihood (Schafer & Graham, 2002) method in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010), which is more powerful and less biased than ad hoc methods of handling missingness (e.g., listwise deletion). This method, also known as direct maximum likelihood (Allison, 2002), works by finding model parameters that maximize the likelihood of each case’s observed data (Wothke, 2000). This approach to handling missing data assumes data are missing at random, that is, missing at random conditional on values observed.

RESULTS

First, we provide descriptive information on the study variables used in the proposed path model. Next, we report the results from structural equation modeling (SEM) examining the path models of previous stigmatization and externalizing behavior on anger and the perpetration and victimization of dating aggression. Direct and mediated relations on dating aggression in the proposed conceptual model were estimated with SEM (Kline, 1998).

Descriptive Information

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among the study variables. The overall mean scores for being the perpetrator and victim of dating aggression indicate that, on average, these types of behaviors (physical, verbal, relational, and threat) occurred infrequently. However, the vast majority of the sample endorsed at least some type of perpetration (79.3%) and victimization (80.2%) experience. More participants endorsed some type of verbal (78.5% perpetration, 79.3% victimization) than physical aggression (33.9% perpetration, 24.0% victimization). Measures of externalizing and stigmatization were stable over 1 year’s time (T1–T2) but were unrelated to each other within or over time. Externalizing behavior at T1, but not T2, was associated with more victimization and perpetration of dating aggression. Neither T1 nor T2 stigmatization was associated with dating aggression. Stigmatization and externalizing behavior at T2, but not at T1, were related to more anger at T3. More anger was associated with more victimization and perpetration of dating aggression. Perpetrating and being a victim of dating aggression were highly related (approaching Kline’s, 1998, definition of excessive correlation of r = .90). However, we chose to consider each of these indicators of dating aggression separately to be consistent with previous literature and to examine whether there were different pathways to each indicator.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ABUSE SEVERITY | 2.98 (1.53) | |||||||

| 2. EXTERNAL1 | −0.08 | 57.87 (6.84) | ||||||

| 3. EXTERNAL2 | 0.02 | 0.60** | 57.86 (6.72) | |||||

| 4. STIGMA1 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 32.08 (19.19) | ||||

| 5. STIGMA2 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .45** | 20.12 (17.12) | |||

| 6. ANGER | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.20* | 0.14 | 0.27** | 55.86 (11.50) | ||

| 7. PDATE | −0.10 | 0.27** | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.46** | 2.14 (1.00) | |

| 8. VDATE | −0.10 | 0.27** | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.44** | 0.88** | 2.08 (0.95) |

Note: For each variable, means and standard deviations (in parentheses) are on the main diagonal. External1 and 2 = Externalizing at T1 and T2, respectively; External2 = T2 Externalizing; Stigma1–2–3 = stigmatization at T1, T2, and T3, respectively; Anger = Anger T3; PDate = T3 perpetrator of dating aggression; VDate = T3 victim of dating aggression. The findings presented in this table were based on data before full information maximum likelihood estimations and were very close to the estimates using full information maximum likelihood.

p<.05.

p<.01.

Predicting Involvement in Dating Aggression over Time

Mplus was used to examine our predictive path model of the direct and mediated relations of stigmatization and externalizing behavior on anger and dating aggression (Muthe´n & Muthe´n, 1998–2010). Although there were few simple correlations between the T1/T2 predictors of externalizing behavior and stigmatization and later T3 dating aggression, a model with meditational effects was conceptually possible given the sizable temporal distance between the assessment of these predictor and outcome variables (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). In addition to the mediated paths to anger from the T1 predictors of externalizing and stigmatization through these variables at T2 and to dating aggression from T2 externalizing and stigmatization through anger, we tested a third mediated path to dating aggression from T1 externalizing and stigmatization through these T2 predictors. Previous work with this sample indicated there would be no indirect effects of T1 stigmatization on dating aggression through T2 stigmatization (Feiring, Simon, & Cleland, 2009). However, we thought it important to assess whether T2 externalizing behavior might mediate longitudinal associations between T1 externalizing behavior and T3 dating aggression without the hypothesized mechanism of anger.

Analyses were conducted using Mplus modeling program because it handles missing data with the full information maximum likelihood approach and provides confidence intervals for direct and mediated effects. Mediated effects were calculated and tested with the resampling method suggested by MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (2004). This method constructs bootstrap confidence intervals for the mediated effects (indirect effect coefficients do not have p values because they are tested via bootstrapping and 95% confidence intervals). The data were resampled a total of 5,000 times. To examine the pathways from externalizing and stigmatization to anger and dating aggression the following pathways were estimated: (a) abuse severity related to T1 externalizing problems and stigmatization; (b) abuse severity, T1 externalizing problems, and stigmatization predicting T2 externalizing problems and stigmatization; (c) abuse severity, T1 and T2 externalizing problems, T1 and T2 stigmatization predicting T3 anger; (d) abuse severity, T1 and T2 externalizing problems, T1 and T2 stigmatization predicting T3 dating perpetration and victimization; and (e) abuse severity, T1 and T2 externalizing problems, T1 and T2 stigmatization, and T3 anger predicting T3 dating perpetration and victimization.

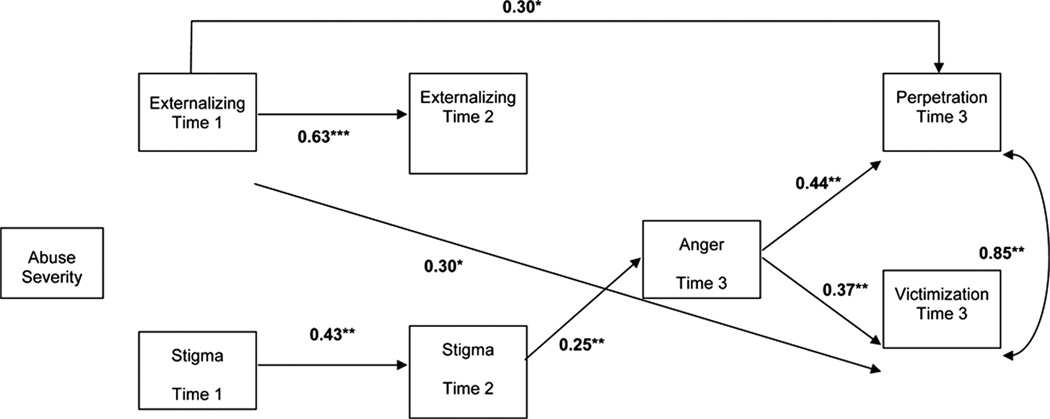

Overall model fit was assessed by two absolute and two incremental fit indices (Hu & Bentler, 1995, 1999). The nonsignificant normal theory weighted least squares chi-square suggested a good fit for the specified model, χ2(2) = 0.48, p = .79, as did the root mean square error of approximation (0.00). The incremental fit indicators, the non-normed fit index (1.06), and comparative fit index (1.00) also showed good model fit. Table 2 shows all path coefficients (β) for the effects leading to each endogenous variable, regardless of significance, and unstandardized regression coefficients, standard errors, critical ratios, and bootstrap 95% confidence intervals to support inferences for each direct effect. Figure 1 illustrates the progression of externalizing behavior and stigmatization over time, and how these processes relate to anger and dating aggression. Overall results showed no significant relations for abuse severity. Contrary to expectation, externalizing behavior was not related to anger, and there was only a direct path from T1 externalizing to dating aggression. As expected, stigmatization at T1 was significantly related to T2 stigmatization, which in turn was significantly related to anger at T3. Anger was significantly related to both perpetrating and being a victim of dating aggression.

TABLE 2.

Structural Equation Model Results for Pathways from Externalizing, Stigmatization, and Anger to Dating Aggression

| Estimate | SE | Est./SE | β | 95% CIL | 95% CIU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing T1 On | ||||||

| Abuse Severity | −0.271 | 0.378 | −0.717 | −0.060 | −1.033 | 0.446 |

| Stigma T1 on | ||||||

| Abuse Severity | 0.924 | 0.992 | 0.921 | 0.074 | −1.064 | 2.824 |

| Externalizing T2 On | ||||||

| Abuse Severity | 0.079 | 0.292 | 0.270 | 0.018 | −0.536 | 0.605 |

| Externalizing T1 | 0.623** | 0.067 | 9.309 | 0.630 | 0.492 | 0.760 |

| Stigma T1 | −0.006 | 0.026 | −0.227 | −0.016 | −0.054 | 0.046 |

| Stigma T2 On | ||||||

| Abuse Severity | 0.400 | 0.679 | 0.588 | 0.036 | −0.885 | 1.786 |

| Stigma T1 | 0.383** | 0.082 | 4.649 | 0.432 | 0.222 | 0.543 |

| Externalizing T1 | 0.040 | 0.184 | 0.220 | −0.016 | −0.310 | 0.409 |

| Anger T3 On | ||||||

| Abuse Severity | 0.683 | 0.755 | 0.904 | 0.091 | −0.729 | 2.211 |

| Externalizing T1 | 0.113 | 0.191 | 0.589 | 0.068 | −0.265 | 0.478 |

| Stigma T1 | 0.010 | 0.066 | 0.147 | 0.016 | −0.128 | 0.128 |

| Externalizing T2 | 0.243 | 0.216 | 1.127 | 0.145 | −0.144 | 0.701 |

| Stigma T2 | 0.170** | 0.060 | 2.835 | 0.253 | 0.044 | 0.281 |

| PDATE On | ||||||

| Abuse Severity | −0.076 | 0.061 | −1.242 | −0.116 | −0.201 | 0.040 |

| Externalizing T1 | 0.044* | 0.018 | 2.521 | 0.303 | 0.007 | 0.075 |

| Stigma T1 | −0.002 | 0.006 | −0.359 | −0.039 | −0.014 | 0.009 |

| Externalizing T2 | −0.026 | 0.019 | −1.354 | −0.174 | −0.058 | 0.016 |

| Stigma T2 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.463 | 0.045 | −0.008 | 0.015 |

| Anger | 0.039** | 0.008 | 4.104 | 0.439 | 0.025 | 0.052 |

| VDATE On | ||||||

| Abuse Severity | −0.075 | 0.060 | −1.256 | −0.119 | −0.193 | 0.041 |

| Externalizing T1 | 0.042* | 0.017 | 2.432 | 0.298 | 0.007 | 0.074 |

| Stigma T1 | −0.005 | 0.005 | −0.976 | −0.106 | −0.016 | 0.006 |

| Externalizing T2 | −0.018 | 0.018 | −0.978 | −0.123 | −0.049 | 0.021 |

| Stigma T2 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.860 | 0.085 | −0.006 | 0.016 |

| Anger | 0.032 | 0.008 | 4.104 | 0.439 | 0.017 | 0.047 |

| VDATE WITH PDATE | 0.614** | 0.086 | 7.126 | 0.848 | 0.486 | 0.834 |

Note: CIL = Confidence Interval Lower Limit; CIU = Confidence Interval Upper Limit; PDate = T3 perpetrator of dating aggression; VDate = T3 victim of dating aggression.

p<.05.

p<.01.

FIGURE 1.

Structural equation model results for predictive pathways from externalizing, stigmatization, and anger to dating aggression perpetration and victimization. Note: The figure shows significant pathways with standardized path coefficients. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

In addition to these direct effects, we examined the indirect paths from T1 externalizing behavior and stigmatization to T3 anger through T2 externalizing behavior and stigmatization. The indirect path from T1 externalizing to T3 anger through T2 externalizing was not significant (B = 0.15, p = .28; β = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.23]). However, the indirect path from T1 stig-matization to T3 anger through T2 stigmatization was significant (B = 0.07, p = .03; β = 0.11, 95% CI [0.01, 0.20]). We also examined the role of anger in the associations between the T2 predictors (externalizing problems and stigmatization) and dating aggression. First, we tested whether T2 externalizing and stigmatization had an indirect effect on dating aggression victimization and perpetration through anger. The indirect pathways from T2 externalizing to perpetrating and being a victim of dating aggression through T3 anger were not significant. The indirect pathways from T2 stigmatization to perpetrating (B = 0.01, p = .01; β = 0.11, p < .05) and being a victim (B = 0.01, p = .02; β = 0.10, p < .05) of dating aggression were significant. Next, we examined whether T1 externalizing and stigmatization had an indirect effect on dating aggression victimization and perpetration through their T2 estimates. None of the indirect pathways from T2 predictors (externalizing, stigmatization) to dating aggression (perpetrating, victimization) were significant.

Finally, we examined whether the tested relations varied according to youths’ age at the time of abuse discovery. Sexual abuse and its public discovery during adolescence coincide with prominent psychosexual developments (e.g., romantic relationships, changes in self-concept, increases in mood lability, and self-consciousness) that might strengthen the relations between externalizing behavior and stigmatization and subsequent problems with anger and dating aggression (Crouter & Booth, 2006; Furman, Brown, & Feiring, 1999; Halpern, 2003; Reimer, 1996; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2004). Because our hypotheses emphasized pathways to and potential mechanisms of dating aggression, we tested a moderated mediation model that examined whether any of the indirect paths from our primary predictors (externalizing problems, stigma) to anger and dating aggression differed for youth who were children (ages 8–11 years) versus adolescents (ages 12–15 years) at time of abuse discovery. Recent treatments of moderated mediation analyses focus on the estimation of interactions between the moderator and the pathways that define an indirect effect (e.g., Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). Within MPlus, this is accomplished using the ‘‘model constraint’’ command to define each conditional indirect effect as the product of its constituent paths at each level of the moderator and then implementing bootstrapping methods to compare the two conditional indirect effects (Muthe´n & Muthe´n, 1998–2010). Accordingly, our moderated mediation model compared the conditional indirect effects from the T1 predictors to T3 anger and from the T2 predictors to dating aggression for each age group. None of the conditional indirect effects were significantly different (all ps > .05), suggesting an absence of moderated mediation.

DISCUSSION

Using longitudinal data, this study focused on the extent to which early externalizing behavior and abuse-specific stigmatization helped explain which youth with a history of CSA were most at risk for subsequent anger and involvement in dating aggression. Abuse severity was not related to earlier indicators of adaptation following abuse discovery or later outcomes. Indicators of severity suggest, but do not directly tap, psychological processes that would be expected to predict anger or dating aggression. In contrast, externalizing behavior and abuse-specific stigmatization showed distinct pathways to involvement in future dating aggression. Externalizing behavior was associated with subsequent dating aggression but not anger, whereas stigmatization was related to dating aggression only through its association with anger. Consistent with the idea that adolescent dating aggression tends to reflect the mutual escalation of conflict, the pathways for predicting perpetration and victimization were very similar (Capaldi & Gorman-Smith, 2003).

Externalizing Behavior and Dating Aggression

As expected, there was some consistency from early externalizing behavior to subsequent dating aggression. For youth exposed to hostile early environments, aggressive behavior may carry forward to interactions with romantic partners (B. Andrews, Brewin, Rose, & Kirk, 2000; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004; Simon & Furman, 2010). Such behaviors may reflect a more general tendency to view conflict as destructive and perceive hostile intentions in others (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge & Pettit, 2003; Simon et al., 2008). Although there was strong stability in externalizing behavior from T1 to T2, it was only externalizing behavior at T1 that significantly predicted dating aggression. T1 externalizing behavior did have stronger bivariate relations with dating aggression than T2 externalizing behavior, which is consistent with T1 bypassing the pathway through T2 externalizing behavior and T3 anger and having significant direct effects on dating aggression in the SEM results. Furthermore, although there was a significant bivariate relation between T2 externalizing behavior and anger, that effect was not significant in the SEM model, and, contrary to expectations, anger did not mediate associations between externalizing behavior and dating aggression.

Interpretation of these unexpected results must be tentative because it is unusual to find variables further rather than closer in time to outcomes showing significant associations. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that development is not always a function of cumulative continuity (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984) and that the timing of abuse discovery along with the earlier emergence of externalizing behavior may reflect a key confluence of experiences for understanding later dating aggression. It is possible that our assessment of externalizing behavior at T1 captured a group of children with early onset of antisocial behavior, the type of pattern found to be related to a history of maltreatment and subsequent relationship violence in both women and men (Odgers et al., 2008). The discovery of CSA is a stressful time for most children and families, and elevated levels of psychological distress in the victim and parent are quite common in the immediate aftermath of abuse discovery (Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, & Steer, 2006; Spaccarelli, 1994). Higher levels of externalizing behavior in children noted during abuse discovery might lay the foundation for aggressive interactions with future romantic partners. In contrast to T1, the T2 assessment occurred when the stress of discovery had diminished and when a greater proportion of the sample were in adolescence, a period when the onset of antisocial behavior is more normative and when antisocial behavior is relatively less predictive of subsequent relationship problems in adulthood (Odgers et al., 2008). One pathway that could be considered in future work is affiliation with deviant peers. Externalizing problems along with the stress of abuse discovery may increase the likelihood that youth become isolated from socially skilled peers and seek out the company of deviant peers who are similarly aggressive. Research suggests that maltreatment is linked to early expressions of antisocial behavior, which in turn are associated with subsequent affiliation with deviant peers and dating aggression (Odgers et al., 2008). If externalizing behavior in childhood and the stress of abuse discovery potentiate affiliation with a deviant peer group, the persistence of such affiliation may lead to CSA youth choosing partners who are more likely to share tendencies to react to conflicts with aggression.

Stigmatization and Dating Aggression

A second pathway from CSA to dating aggression through anger was abuse specific. Although anger was not measured prior to subsequent dating aggression, the findings indicate that the persistence of abuse-specific stigmatization over the year following abuse discovery may place CSA youth at risk for subsequent problems with regulating anger and engaging in dating aggression. Whereas previous research has linked CSA with anger (e.g., Negrao, Bonanno, Noll, Putnam, & Trickett, 2005) and anger with dating aggression (e.g., Sanford, 2007; Wolfe et al., 1998), this is the first study to provide longitudinal evidence for early predictors of the anger-dating aggression association among abused youth.

The anger measured in this study reflected hostility and the desire to strike out at others. It is this kind of explosive anger that has been hypothesized to be activated in the shame–rage spiral (Scheff, 1987; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). The current findings are consistent with this idea and suggest that the intensely negative self-directed thoughts and feelings that compose stigmatization can be turned outward in a self-defensive process in which the partner is viewed in negative terms. In other words, one strategy for alleviating the highly negative experience of stigmatization and for preserving some self-esteem is to shift blame and negative feelings onto the partner, which can lead to anger and perpetrating dating aggression. Stigmatization was also linked to victimization through anger. Taken together, the findings support the idea that early abuse-specific stigmatization puts youth at risk for future shame–rage difficulties in their romantic relationships. In this way, stigmatization may heighten the tendency to experience rage during conflict, thereby increasing the risk for destructive retaliation against the partner and, in turn, increasing the odds that the partner will become angry and retaliate in kind.

Limitations

Although our findings concern a relatively large number of prospectively assessed CSA victims, limits to the findings are acknowledged. The within-group design could not address the issue of whether CSA youth compared to similar youth without an abuse history, or those with a history of other forms of maltreatment, were at greater risk for anger and dating aggression. The external validity of the study was limited to individuals for whom the abuse was reported to the appropriate authorities, a small minority of those who experience CSA (Widom & Morris, 1997). The study relied exclusively on reports of youth behavior, although both youth and parent/ teacher measures were collected, albeit on different constructs. Observational measures of couples’ conflict patterns and physiological assessments of emotional reactivity during conflict interactions would offer objective assessments of affect and behavior regulation during romantic relationship conflict. Our ability to detect age-moderated effects may have been limited by the wide age range of the sample and by the fact that age of discovery was not necessarily the same as age at which the abuse began. Our sample was not large enough to consider age moderation as a function of the four abuse-discovery by when-abuse-began subgroups (e.g., discovered-began-ended childhood; discovered-began-ended adolescence; discovered adolescence, began-ended childhood; discovered adolescence, began childhood-ended-adolescence). Although our sample was unique for including male victims of CSA, the sample size was too small for sufficiently powered tests of gender-moderated effects. However, estimation of the SEM model for women only showed the strength and direction of path coefficients were similar to the model for the total sample suggesting gender did not operate as a moderator. It will be challenging and important for future work to collect large-enough CSA samples to examine age and gender moderation; to be feasible, we suspect such an effort will require multicite collaboration.

Given the nonexperimental nature of the data and that all key variables were not assessed at each time point, the findings are not conclusive concerning causal direction. It was not possible to examine the extent to which stigmatization and externalizing behavior contributed to changes in anger and dating aggression over time because these latter variables were measured only at T3. For example, we could not examine whether earlier anger in association with stigmatization was an unmeasured factor that might explain the association between stigmatization and subsequent anger. Furthermore, the stronger relation between anger and dating aggression could be attributed, to some extent, to concurrent measurement whereas the weaker or nonsignificant relations from the T1 and T2 variables to these T3 variables could be attributed to the 5- to 6-year interval between earlier and subsequent assessments. These limitations of design for drawing causal inferences notwithstanding, the current findings linking earlier stigma-tization and externalizing behavior with relatively distant experiences of anger and dating aggression suggest the merit of further longitudinal work on how experiences of stigmatization, externalizing behavior, and anger may increase the risk for dating aggression in CSA youth.

Clinical Implications

The strong emotions that occur with the sexual and intimacy demands of dating relationships may be especially challenging for adolescents with CSA histories and potentially evoke a resurgence of abuse-related reactions (Wekerle & Wolfe, 2003). Resurgent stigmatization may be overt or manifest more covertly as generalized anger problems rooted in earlier stigmatization. Careful clinical assessments of anger and abuse stigmatization should facilitate appropriate treatment planning for youth with CSA histories. Targeting anger regulation may require skills training as well as trauma-focused strategies to reduce abuse stigmatization. Efforts to build specific romantic relationship competencies (e.g., conflict resolution/communication skills; affect regulation in conflict situations) are also likely to be important for reducing the risk of dating violence among youth with CSA histories (Wolfe et al., 2003).

Our findings linking early abuse reactions to subsequent anger and dating aggression underscore the need for early intervention among both child and adolescent CSA victims, including those that target stigmatization, externalizing behavior, anger management, and romantic relationship competencies. For example, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is an evidence-based intervention that includes exposure (e.g., creating trauma narratives) and skill building (e.g., relaxation, affect modulation, cognitive coping) components that reduce the distorted abuse attributions linked to anger and dating aggression in the current study (Deblinger et al., 2006). The caregiver component of TF-CBT builds parenting skills and is associated with decreases in the early externalizing behavior that we found to be directly associated with dating aggression (Deblinger, Mannarino, Cohen, Runyon, & Steer, 2011). In these ways, early trauma-focused interventions may help to prevent later dating aggression.

Nonetheless, anger regulation and aggressive behavior have not been the central targets of treatment for CSA youth. Although a focus on internalizing symptoms, such as PTSD, among the predominantly female population of sexually abused youth is understandable, our findings suggest that greater sensitivity to the links between cognitive and affective reactions to the abuse and aggression may also be useful. For example, CSA youth might benefit from some of the cognitive, affective, and behavioral coping strategies found within interventions to reduce aggressive and antisocial behaviors such as Alternatives for Families-CBT (e.g., childtargeted anger control, social problem-solving and friendship-making skills training and parent management training in appropriate and effective discipline; Kolko et al., 2009). By reducing externalizing behaviors and promoting less hostile processing and interpretation of social information, these interventions should promote some of the social competencies that are important for later romantic relationships (Simon et al., 2008).

Contributor Information

Candice Feiring, Center for Youth Relationship Development, The College of New Jersey.

Valerie A. Simon, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University

Charles M. Cleland, New York University College of Nursing

Ellen P. Barrett, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data (Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07–136) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brewin CR, Rose S, Kirk M. Predicting PTSD symptoms in victims of violent crime: The role of shame, anger and childhood abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:69–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Foster SL, Capaldi DM, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication, and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:195–208. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM. From child victim to adult victim: A model for predicting sexual revictimization. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:28–38. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Arnold S, Smith J. Childhood sexual abuse and dating experiences of undergraduate women. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:39–48. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett D, Sullivan MW, Lewis M. Young children’s adjustment as a function of maltreatment, shame and anger. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:311–323. doi: 10.1177/1077559505278619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Trauma Symptom Inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Elliott DM, Harris K, Cottman A. Trauma Symptom Inventory: Psychometrics and association with childhood and adult victimization in clinical samples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10:387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Gorman-Smith D. The development of aggression in young male/female couples. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 243–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Wherry JN, Newlin C, Crutchfield A, Dykman R. The Abuse Dimensions Inventory: Initial data on a research measure of abuse severity. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:569–589. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino CE, Meyer-Bahlburg HF, Albert JL, Gaines R. Cross-gender behavior and gender conflict in sexually abused girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:940–947. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covert MV, Tangney JP, Maddux JE, Heleno NM. Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and interpersonal problem solving: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2003;22:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. The Penn State University family issues symposia series. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. Romance and sex in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Risks and opportunities. [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Runyon MK, Steer RA. Trauma- focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:67–75. doi: 10.1002/da.20744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Steer RA. A follow up study of a multi-site, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1474–1484. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000240839.56114.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Giuffre D, Tremblay GC, Peterson L. A closer look at the nature of intimate partner violence reported by women with a history of child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:116–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:349–371. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:1–22. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Cleland C. Childhood sexual abuse and abuse-specific attributions of blame over 6 years following discovery. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:1169–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Rosenthal S, Taska L. Stigmatization and the development of friendship and romantic relationships in adolescent victims of sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:311–322. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005004003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Simon VA, Cleland CM. Childhood sexual abuse, stigmatization, internalizing symptoms, and the development of sexual difficulties and dating aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:127–137. doi: 10.1037/a0013475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska L. The persistence of shame following childhood sexual abuse: A longitudinal look at risk and recovery. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:337–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559505276686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska LS, Chen K. Trying to understand why horrible things happen: Attribution, shame and symptom development following sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7:26–41. doi: 10.1177/1077559502007001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska LS, Lewis M. The role of shame and attribution style in children’s and adolescents’ adaptation to sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Ortho-psychiatry. 1985;55:530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GJ, Fitness J, Blampied NM. The link between attributions and happiness in close relationships: The roles of depression and explanatory style. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaty K, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The daily social and emotional worlds of adolescents who are psychologically maltreated by their romantic partners. Jounrnal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:310–323. [Google Scholar]

- Godbout N, Sabourin S, Lussier Y. Child sexual abuse and adult romantic adjustment: Comparison of single- and multiple-indicator measures. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:693–705. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT. Biological influences on adolescent romantic and sexual behavior. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Harper F, Arias I. The role of shame in predicting adult anger and depressive symptoms among victims of child psychological maltreatment. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;19:367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Bates L, Smutzler N, Sandin E. A brief review of the research on husband violence. Part I: Maritally violent versus nonviolent men. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:65–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equations modeling: concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Talbot NL, Cicchetti D. Childhood abuse and current interpersonal conflict: The role of shame. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsfogel KM, Grych JH. Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationships: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:505–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Dorn LD, Bukstein OG, Pardini D, Holden EA, Hart J. Community vs. clinic-based modular treatment of children with early-onset ODD or CD: A clinical trial with 3-year follow-up. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;37:591–609. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. Shame: The exposed self. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Liem JH, Boudewyn AC. Contextualizing the effects of childhood sexual abuse on adult self- and social functioning: An attachment theory perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:1141–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligezinska M, Firestone P, Manion IG, McIntyre J, Ensom R, Wells G. Children’s emotional and behavioral reactions following the disclosure of extrafamilial sexual abuse: Initial effects. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1996;20:111–125. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Barry TD, Pardini DA. Anger control training for aggressive youth. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. pp. 263–281. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthe´n LK, Muthe´n BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Negrao CI, Bonanno G, Noll JG, Putnam FW, Trickett PK. Shame, humiliation and childhood sexual abuse: Distinct contributions and emotional coherence. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:350–363. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols TR, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Botvin GJ. Sex differences in overt aggression and delinquency among urban minority middle school students. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moffit TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Caspi A. Female and male antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt M, Freyd J. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. Advance online publication; 2011. Trauma and negative underlying assumptions in feeling shame: An exploratory study. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer MS. ‘‘Sinking into the ground’’: The development and consequences of shame in adolescence. Developmental Review. 1996;16:321–363. doi: 10.1006/drev.1996.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford K. Hard and soft emotion during conflict: Investigating married couples and other relationships. Personal Relationships. 2007;14:65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sex. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. pp. 189–231. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheff TJ. The shame-rage spiral: A case study of an interminable quarrel. In: Lewis HB, editor. The role of shame in symptom formation Vol. XII. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 109–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shortt JW, Capaldi DM, Dishion TJ, Bank L, Owen LD. The role of adolescent friends, romantic partners, and siblings in the emergence of the adult antisocial lifestyle. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:521–533. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon VA, Furman W. Interparental conflict and adolescents romantic relationship conflict. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:188–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon VA, Kobielski S, Martin S. Conflict beliefs, goals, and behavior in romantic relationships during late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:324–335. [Google Scholar]

- Spaccarelli S. Stress, appraisal, and coping in child sexual abuse: A theoretical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:340–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Rutter M. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanston HY, Parkinson PN, O’Toole BI, Plunkett AM, Shrimpton S, Oates RK. Juvenile crime, aggression and delinquency after sexual abuse: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Criminology. 2003;43:729–749. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing RL. Shame and guilt. New York, NY: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Fletcher C, Gramzow R. Shamed into anger? The relation of shame and guilt to anger and self-reported aggression. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1992;62:669–675. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Hill-Barlow D, Marschall DE, Gramzow R. Relation of shame and guilt to constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;70:797–809. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaes S, Stegge H, Olthof T, Bushman BJ, Nezlek JB. Turning shame inside-out: ‘‘Humiliated fury’’ in young adolescents. Emotion. 2011;11:786–793. doi: 10.1037/a0023403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Wolfe DA. Child maltreatment. In: Mash EJ, Russell RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. pp. 632–684. [Google Scholar]

- West CM, Williams LM, Siegel JA. Adult sexual revictimization among Black women sexually abused in childhood: A prospective examination of serious consequences of abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:49–57. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Widom CS. Intimate partner violence among abused and neglected children in young adulthood: The mediating effects of early aggression, antisocial personality, hostility, and alcohol problems. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29:332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of child victimization: Part 2. Childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Williams TS, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W, Laporte L. Risk models of dating aggression across different adolescent relationships: A developmental psychopathology approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:622–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman A. Development and validation of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Lefebvre L. Factors associated with abusive relationships among maltreated and nonmaltreated youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:61–85. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman A, Grasley C. Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: The role of child maltreatment and trauma. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:406–415. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman A, Grasley C, Reitzel-Jaffe D. Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: A controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:279–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Romantic relationships of young people with childhood and adolescent onset antisocial behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:231–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1015150728887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W. Longitudinal and multigroup modeling with missing data. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches and specific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 219–240. [Google Scholar]