Abstract

The transcriptional program that regulates the differentiation of endothelial precursor cells into a highly organized vascular network is still poorly understood. Here we explore the role of SOX7 during this process, performing a detailed analysis of the vascular defects resulting from either a complete deficiency in Sox7 expression or from the conditional deletion of Sox7 in FLK1-expressing cells. We analysed the consequence of Sox7 deficiency from E7.5 onward to determine from which stage of development the effect of Sox7 deficiency can be observed. We show that while Sox7 is expressed at the onset of endothelial specification from mesoderm, Sox7 deficiency does not impact the emergence of the first endothelial progenitors. However, by E8.5, clear signs of defective vascular development are already observed with the presence of highly unorganised endothelial cords rather than distinct paired dorsal aorta. By E10.5, both Sox7 complete knockout and FLK1-specific deletion of Sox7 lead to widespread vascular defects. In contrast, while SOX7 is expressed in the earliest specified blood progenitors, the VAV-specific deletion of Sox7 does not affect the hematopoietic system. Together, our data reveal the unique role of SOX7 in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis during embryonic development.

Keywords: Vascular development, SOXF, Endothelium

Highlights

-

•

Sox7 is expressed at the onset of endothelial specification from mesoderm.

-

•

Sox7 deficiency does not impact the emergence of the first endothelial progenitors.

-

•

Sox7 complete knockout and FLK1-specific deletion lead to widespread vascular defects.

-

•

VAV-specific deletion of Sox7 does not affect the hematopoietic system.

-

•

Unique role of SOX7 in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis during embryonic development

1. Introduction

The development of the vascular system involves a complex array of processes necessary to regulate the dynamic nature of the emerging vascular network. During development, the first blood vessels form in the extra-embryonic yolk sac via vasculogenesis, which initiates following the formation of blood islands from mesodermal progenitors (Ferkowicz and Yoder, 2005). Cells on the inside of the blood islands differentiate into blood cells, whereas cells on the outside differentiate into endothelial precursor cells (EPCs), which migrate and associate to form a primitive vascular plexus (Herbert and Stainier, 2011). In the embryo proper, EPCs migrate to form endothelial chords that differentiate into the major arteries and veins (De Val and Black, 2009). The primitive extra and intra-embryonic vascular network subsequently undergoes angiogenesis involving the remodelling and expansion of blood vessels resulting in the formation of a hierarchically organized vascular network (Risau and Flamme, 1995). The transcriptional network regulating the identity and behaviour of EPCs involved in vascular development is extremely complex and remains poorly understood.

The Sox family of genes encodes a group of transcription factors that all share a high mobility group (HMG) DNA binding domain and recognise the AACAAT consensus sequence (Schepers et al., 2002). The SOX F subgroup contains SOX7, SOX17 and SOX18, and a growing body of evidence indicates that they have important roles in cardiovascular development (Francois et al., 2010, Lilly et al., 2017). However, SOX17 has pleiotropic functions and regulates a variety of processes including: definitive endoderm specification (Kanai-Azuma et al., 2002), fetal hematopoietic stem cell proliferation (Kim et al., 2007), oligodendrocyte development (Sohn et al., 2006) and arterial specification during cardiovascular development (Corada et al., 2013). The role of SOX18 appears to be more restricted with deficiency in this factor leading to specific defects in lymphangiogenesis (Francois et al., 2008). In contrast, the role and function of SOX7 is still poorly defined. SOX7 is expressed in primitive endoderm (Futaki et al., 2004, Murakami et al., 2004) and in endothelial cells at various stages of vascular development. These include the mesodermal masses that give rise to blood islands in gastrulating embryos (Gandillet et al., 2009), and the vascular endothelial cells of the dorsal aorta, intersomitic vessels and cardinal veins in more developed embryos (Hosking et al., 2009, Kim et al., 2016, Takash et al., 2001). Gross morphological examination of Sox7−/− mouse embryos suggests potential vascular defects (Wat et al., 2012); more recently, it was shown that the conditional deletion of Sox7 in Tie2 expressing endothelial cells results in branching and sprouting angiogenic defects at E10.5 (Kim et al., 2016). Despite these recent advances, a comprehensive analysis of the developing vascular network encompassing both vasculogenic and angiogenic processes in SOX7 deficient embryos has not yet been undertaken.

Here, we performed a detailed analysis of the vascular defects resulting from either a complete deficiency in Sox7 expression or from the conditional deletion of Sox7 in FLK1-expressing cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. ESC culture and differentiation

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) were cultured and differentiated as previously described (Sroczynska et al., 2009). Embryoid bodies (EBs) were routinely maintained up to day 3, and FLK1+ cells were isolated and cultured as previously described (Fehling et al., 2003, Lancrin et al., 2009).

2.2. Generation of Sox7 knockout mouse lines

Targeted Sox7 ESC clone B9 (International Knockout Mouse Consortium) was injected into mouse blastocysts. Resultant chimaeras were crossed with C57BL/6 mice. Subsequent generations were crossed with PGK-Cre mice to excise the neomycin cassette and exon 2 of the Sox7 gene, resulting in the generation of a LacZ-tagged null allele (Sox7LacZ/WT). Alternatively to generate the Sox7-floxed allele, mice were crossed with an actin-FLP transgenic line resulting in the excision of both IRES-LacZ and neomycin cassettes that are flanked by FRT site (International Knockout Mouse Consortium). After eight backcrosses on C57BL/6, mice were either inter-crossed to generate Sox7fl/fl or crossed with Flk1-cre (Motoike et al., 2003) or Vav-Cre (de Boer et al., 2003) transgenic lines to excise in a tissue specific manner the exon 2 of Sox7 that is flanked by LoxP sites.

2.3. Timed matings

Timed matings were set up between: heterozygous male and female Sox7LacZ/WT mice, heterozygous Sox7fl/wt Flk1-Cre male and Sox7fl/fl or Sox7fl/− female mice. The morning of vaginal plug detection was embryonic day (E) 0.5. All animal work was performed under regulation governed by the Home Office Legislation under the Animal Scientific Procedures Act (ASPA) 1986.

2.4. QRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Rneasy Mini/Micro plus Kit (Qiagen), and 2 μg of which was used to generate cDNA using the Omniscript reverse transcriptase kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real time PCR were performed on an ABI 7900 system (Applied Biosystems) using the Exiqon universal probe library (Roche). Gene expression was calculated relative to β-actin using the ΔΔCt method.

2.5. Whole mount and section staining

Embryos were stained using a rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (1:500) (BD biosciences; 553,370) and a goat anti-rat AF555 secondary antibody (1:1000) (Invitrogen) as previously described (Yokomizo et al., 2012). Z-stack images were taken using a two-photon confocal microscope with a 5 × objective (Leica). E10.5 embryo sections were stained as previously described (Thambyrajah et al., 2016) using a goat anti-SOX7 antibody (1:200) (R&D systems; AF2766) and a donkey anti-goat AF647 antibody (1:2000) (Invitrogen). Subsequently, embryos were stained with a rat anti-cKit antibody (1:1000) (BD biosciences; 553,868), and a rabbit anti-pan-RUNX antibody (1:1000) (Abcam; ab92336) before staining with a goat anti-rat AF488 and a goat anti-rabbit antibody (both 1:2000) (both Invitrogen). Yolk sacs were isolated and flat mounted with DAPI as previously described (Frame et al., 2016) before imaging. Specific labelling of primary antibodies was determined by comparison with no primary antibody stained controls.

2.6. Flow cytometry

Cells were disaggregated by trypsinisation, and incubated with combinations of conjugated monoclonal antibodies on ice. Analyses were performed on a BD LSRII (BD Biosciences). Data were analysed with FlowJo (TreeStar), gating first on the forward scatter versus side scatter to exclude non-viable cells.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Sample sizes were chosen based on previous experimental experience. Student's t-test was used to assess the differences between two populations in embryo experiments. * P-value < 0.05, **P-value < 0.01, *** P-value < 0.001.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. SOX7 is expressed in EPCs at the onset of endothelial specification from mesoderm

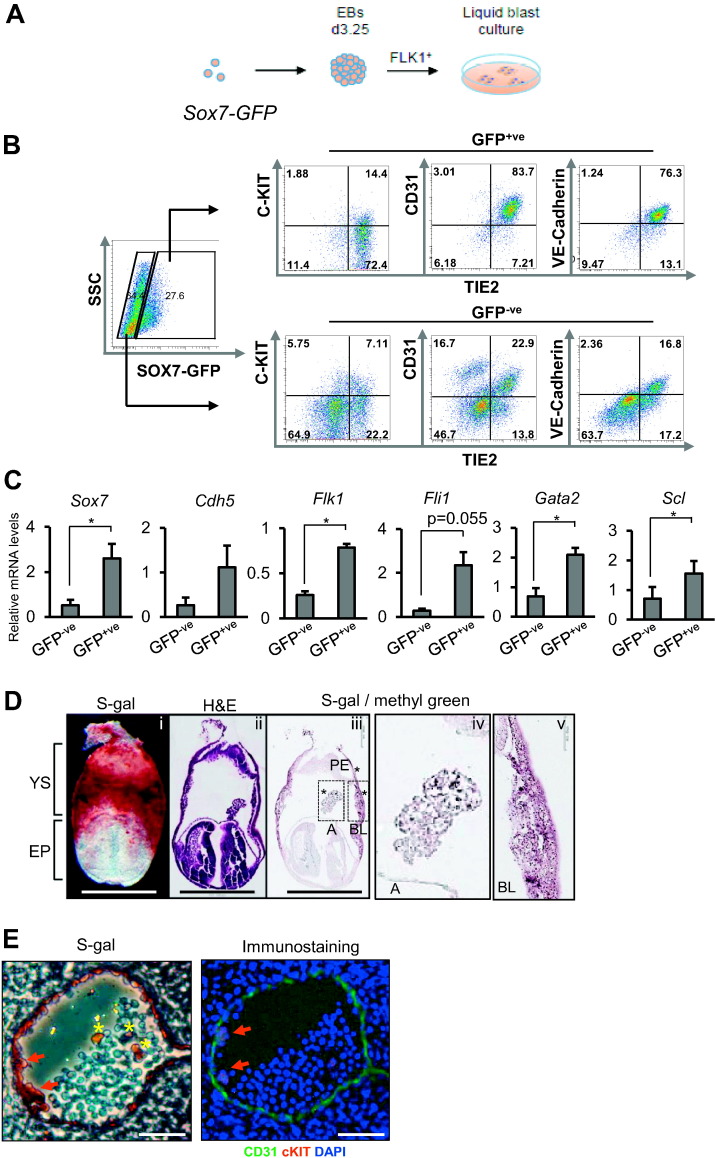

To define at the cellular level the expression of SOX7 during the earliest step of cardiovascular specification from mesoderm, we used an embryonic stem cell (ESC) line carrying a BAC transgene with the first exon of Sox7 replaced by a Gfp reporter cDNA (Gandillet et al., 2009). These ESCs were differentiated in vitro to mesoderm via embryoid body (EB) formation (Fehling et al., 2003). This differentiation process led to the generation of a FLK1+ mesoderm population that was isolated and further differentiated to a TIE2+ cKIT+ cell population containing both hemogenic endothelial and EPCs as previously described (Lancrin et al., 2009). FLK1+ cells sorted from Sox7-GFP EBs were cultured as a monolayer and analysed after 2 days of culture (Fig. 1A). The SOX7-GFP+ fraction was strongly enriched for the expression of the endothelial marker TIE2, VE-Cadherin and CD31, and to a lesser extent, for c-KIT when compared to the SOX7-GFP− fraction (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the SOX7-GFP+ fraction had significantly higher transcript levels of Flk1, Gata2, and Scl genes, while there were also higher transcript levels of Fli1 and Cdh5 (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these data indicate that in vitro, SOX7 is expressed in a very large fraction EPCs at the onset of endothelial specification from mesodermal precursors.

Fig. 1.

SOX7 is expressed at the onset of endothelial differentiation from mesodermal precursors. (A) FLK1+ cells were sorted from day 3.25 Sox7-Gfp embryoid bodies (EBs) and cultured in 2D culture. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of SOX7-GFP+ and SOX-GFP− fractions at day 2 of culture. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) QRT-PCR analysis for the expression of the indicated genes in sorted SOX7-GFP+ and SOX7-GFP− fractions at day 2 of the culture. Error bars indicate ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments), Student's paired two-tailed t-test. (D) E7.5 Sox7LacZ/WT embryos: (i) whole mount S-gal staining, (ii) hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining on section, (iii) S-gal and methyl green staining on section, (iv) close-up image of allantois from the S-gal staining, (v) close-up image of blood island from the S-gal staining. YS: yolk sac, EP: embryo proper, A: allantois, BL: blood island, PE: primitive endoderm. Scale bars: 500 μm. (E) E10.5 Sox7LacZ/WT embryos. Left panel: S-gal staining on a section from dorsal aorta. Right: Immunostaining on the following section. Red arrows indicate emerging hematopoietic clusters. Yellow asterisks indicate SOX7::S-gal+ blood cells. Scale bars: 50 μm.

To investigate the pattern of SOX7 expression during in vivo development, mouse embryos heterozygous for a Sox7-LacZ null allele were generated. Whole mount S-gal staining of E7.5 embryos revealed the widespread presence of SOX7:LACZ-expressing cells in the yolk sac region of the developing conceptus in agreement with previously published data (Gandillet et al., 2009) (Fig. 1D). Further S-gal staining of E7.5 embryo sections confirmed the expression of SOX7 in the blood islands, allantois and primitive endoderm (Fig. 1D). In E10.5 embryos, S-gal staining highlighted SOX7::LACZ-expressing cells in the endothelium lining of the dorsal aorta (Fig. 1E). Additionally, immunostaining revealed that CD31+ c-KIT+ hematopoietic clusters expressed SOX7 (Fig. 1E, red arrows) whereas few hematopoietic cells within the aortal lumen also expressed SOX7 (Fig. 1E, yellow asterisks). These data confirm that SOX7 is expressed in the blood islands during the emergence of the first EPCs, as well as at later stages in endothelial cells during vascular development. It is interesting to note that SOX7 also appears to be expressed in hemogenic endothelium of the dorsal aorta since emerging clusters of blood cells do express SOX7. Given the very early onset of Sox7 expression during the specification of the cardiovascular system, it is important to define how early during development this transcription factor is required for vasculogenesis and angiogenesis.

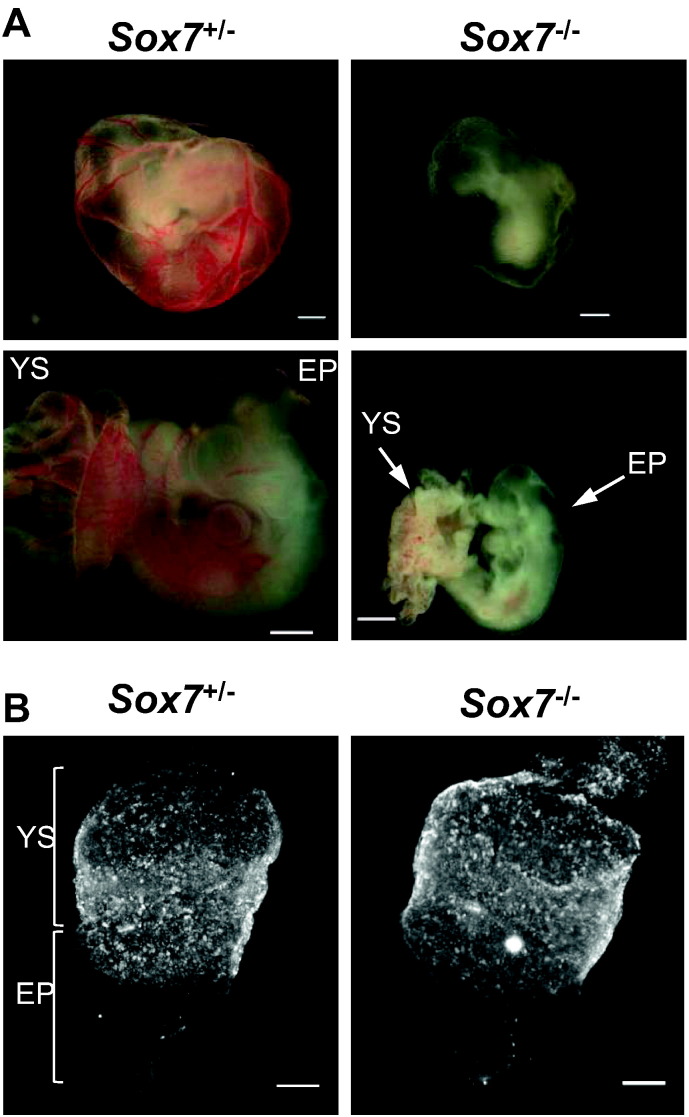

3.2. Sox7 complete knockout embryos have profound defects in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis

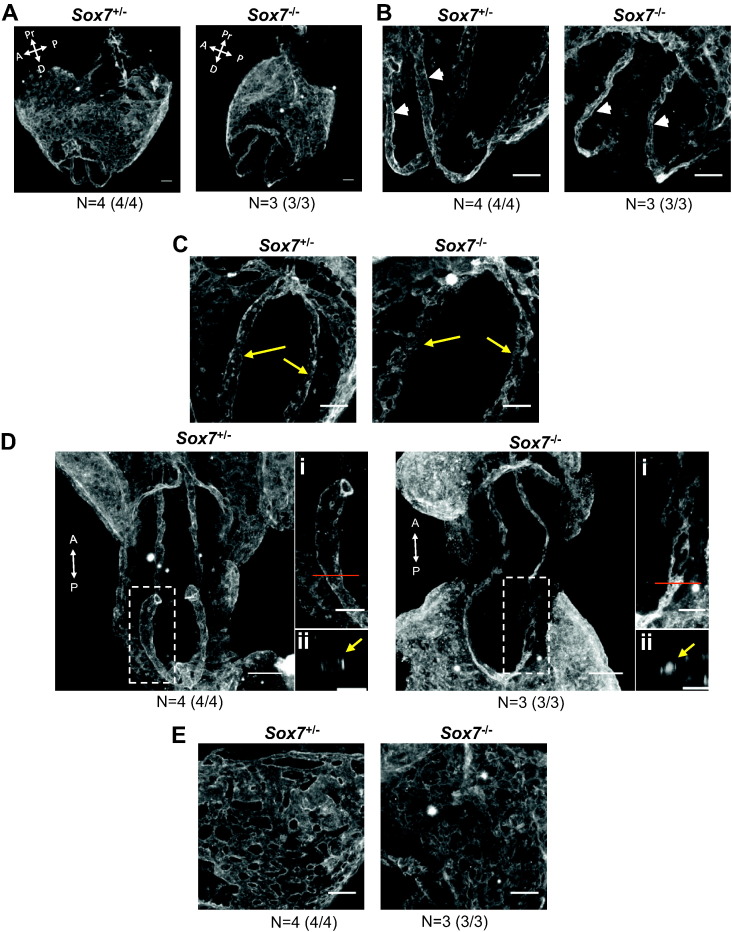

In order to elucidate the role of Sox7 during embryonic development, we first generated complete Sox7 knockout embryos (Sox7−/−) on homogenous genetic background by backcrossing Sox7lacZ/+ mice on C57Bl/6 then by inter-crossing these transgenic mice. The LacZ cassette was inserted at the beginning of exon 2 and therefore fully disrupts the expression of Sox7. Complete deficiency in Sox7 on this homogenous background led to a fully penetrant embryonic lethality phenotype by E10.5 characterised by severe growth retardation as well as an absence of large blood vessels in the yolk sac (Fig. 2A) as previously observed (Wat et al., 2012). To understand how these defects occurred, we investigated the formation of the vascular system prior to E10.5, a developmental time point at which Sox7 deficiency resulted in lethality in all embryos examined. Whole mount PECAM1 staining at E7.5 revealed that Sox7 deficiency did not affect the overall generation of PECAM1+ primordial EPCs (Fig. 2B). However, one day later by E8.5, Sox7−/− embryos already displayed notable defects in the developing vascular networks which are formed by vasculogenesis (Fig. 3A). The development of the anterior region of the paired dorsal aorta was relatively unaffected (Fig. 3B, white arrowheads), but the posterior region displayed areas of highly unorganised endothelial cords rather than a distinct paired dorsal aorta (Fig. 3C, yellow arrows and Supplemental video 1). In addition, the posterior regions of the dorsal aorta were not lumenized in Sox7−/− embryos (Fig. 3D). Finally, whilst a primitive vascular plexus formed within the yolk sac of Sox7−/− embryos, the vascular network appeared disorganized compared to that of the control embryos (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 2.

SOX7 deficient embryos show dramatic growth delay at E10.5 but generate primordial PECAM1+ cells at E7.5. (A) Light microscope images of heterozygous (Sox7+/−) and Sox7 knockout (Sox7−/−) embryos at E10.5. Top panel: images of embryos embedded within their yolk sacs, bottom panel: images of embryo proper and yolk sac. (B) Whole mount PECAM1 staining of heterozygous (Sox7+/−) and Sox7 knockout (Sox7−/−) yolk sacs embryos at E7.5. YS: yolk sac, EP: embryo proper.

Fig. 3.

SOX7 deficient embryos show defects in the dorsal aorta and vascular plexus of the yolk sac at E8.5. (A) Whole mount PECAM1 staining of heterozygous (Sox7+/−) and Sox7 knockout (Sox7−/−) embryos and yolk sacs at E8.5 (5–6 somite pairs). 3D projection of the embryo embedded within its yolk sac. White arrows indicate anterior (A), posterior (P), distal (D) and proximal (Pr) axes. (B) Anterior view of the dorsal aorta (white arrowheads). (C) Posterior tip of the dorsal aorta (yellow arrows). (D) Whole mount PECAM1 staining of Sox7+/− and Sox7−/− E8.5 embryos (3–5 somite pairs). The boxes denote area of magnification: (i) magnified view of dorsal aorta, red bar denotes cross section area, (ii) cross section of dorsal aorta lumen. (E) Details of the yolk sac vasculature. Scale bars: 100 μm. Data shown are representative of at least 3 embryos with 100% penetrance of the phenotype observed for knockout embryos.

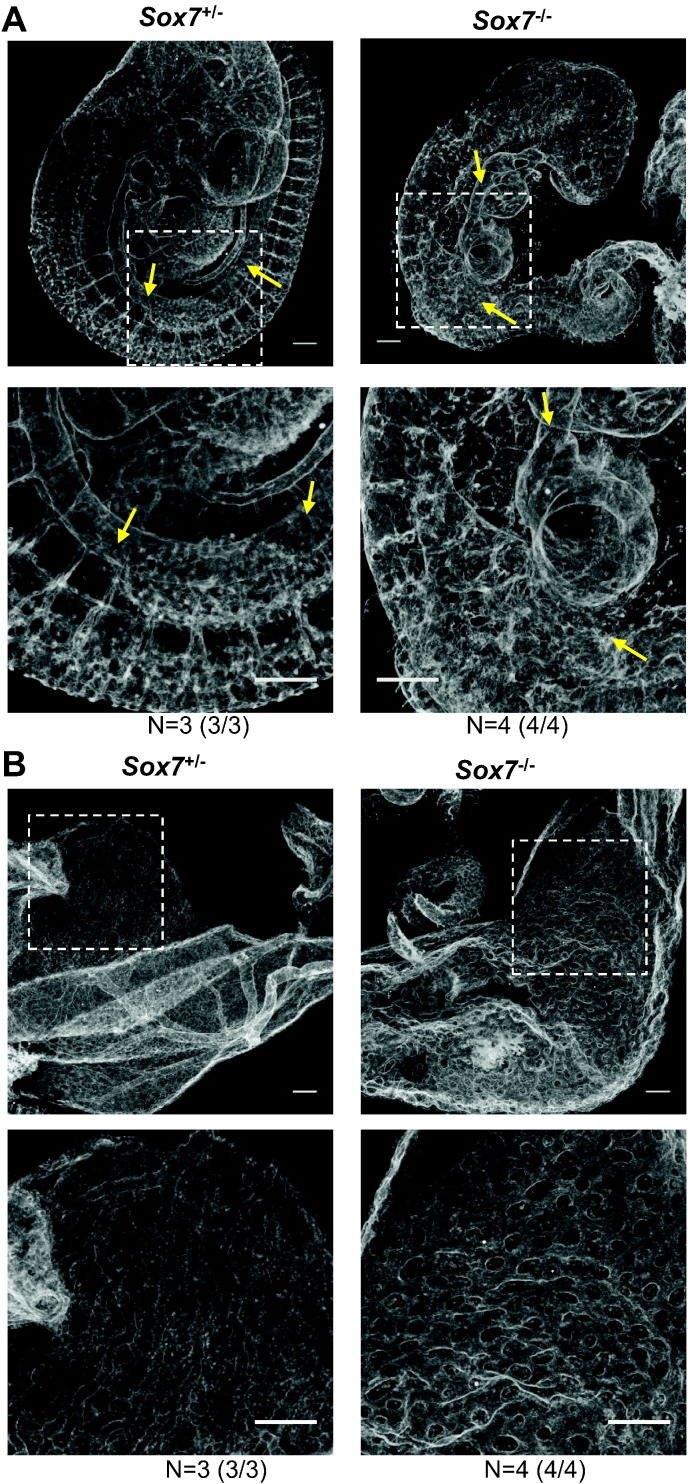

By E10.5, whole mount PECAM1 staining revealed that Sox7 deficiency led to extremely severe vascular defects both in the embryo proper and in the yolk sac (Fig. 4A and B). In Sox7−/− embryos there was an absence of a definitive dorsal aorta in the posterior region of the embryo (Fig. 4A, yellow arrows), indicating that the dorsal aorta did not recover from the initial vasculogenic defects observed at E8.5. Furthermore, the highly unorganised nature of the vascular networks indicates considerable angiogenic remodelling defects resulting from Sox7 deficiency. At E10.5, the yolk sac vasculature of Sox7−/− embryos was arrested at the primitive vascular plexus stage, with a complete absence of vascular remodelling (Fig. 4B). Together these findings demonstrate that SOX7 is critically required for both vasculogenesis and vascular remodelling during angiogenesis. A detailed study of sprouting defect in the retina upon Cdh5-CreER induced deletion of Sox7 has recently been published by Kim et al. (Kim et al., 2016), suggesting that SOX7 is important for both remodelling and sprouting during angiogenesis.

Fig. 4.

By E10.5 SOX7 deficient embryos have profound and widespread defects in vascular development. Whole mount PECAM1 staining of heterozygous (Sox7+/−) and Sox7 knockout (Sox7−/−) embryos at E10.5. (A) Embryo proper, white boxes indicate areas of magnification. Yellow arrows indicate dorsal aorta. (B) Yolk sac vasculature, white boxes indicate areas of magnification. Scale bars: 250 μm.

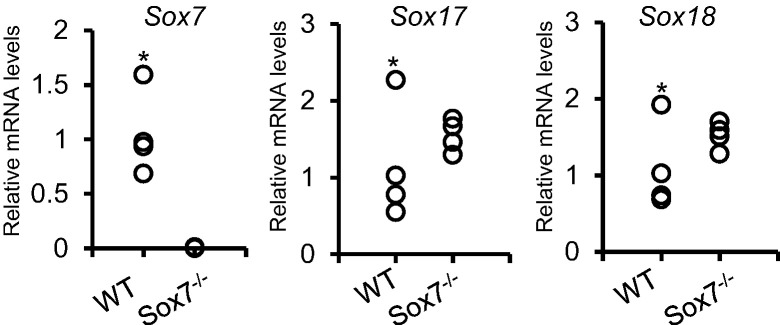

Unlike other intra-embryonic vessels and arteries, the nascent dorsal aortae originate from paired lateral cords that are formed by the migration and aggregation of angioblasts (Drake and Fleming, 2000, Sato, 2013). The fact that the posterior part of the dorsal aorta is affected in Sox7 deficient embryos strongly suggests an early defect in cord assembly at a vasculogenesis stage. It has been well characterised that there is redundancy and compensation between SOXF family members in controlling vascular development (Hosking et al., 2009, Matsui et al., 2006, Zhou et al., 2015). The conditional knockout of SOX7 in TIE2 expressing endothelial cells using mice from a mixed genetic background, resulted in relatively minor vascular defects such as a decrease in the diameter of the dorsal aorta (Zhou et al., 2015). These relatively minor defects reported by Zhou and collaborators are most likely due to compensation by SOX17 and SOX18 rather than truly a result of Sox7 deletion in TIE2-expressing cells. Indeed, it was shown that in Sox18−/− mice of a mixed genetic background SOX7 and SOX17 were upregulated and substituted for SOX18 (Hosking et al., 2009). Given this known redundancy and compensation among the three SOXF genes, we examined transcript levels for Sox17 and Sox18 in Sox7−/− embryos relative to Sox7+/+ embryos (Fig. 5). This analysis revealed an increase in the expression of both Sox17 and Sox18, suggesting possible compensation of SOX7 deficiency by SOX17 and SOX18. However, even with the compensatory activity by SOX17 and SOX18, Sox7 deficiency resulted in massive vasculogenic and angiogenic defects. Together these data support a critical and unique role for SOX7 in the development of the vascular system.

Fig. 5.

Change in the expression levels of Sox17 and Sox18 in SOX7 deficient embryos. PCR analysis of Sox7, Sox17 and Sox18 expression levels in wild type (WT) and Sox7 knockout (Sox7−/−) embryos at E10 (n = 4).* Denotes the same WT embryo with overall higher levels of Sox7, Sox17 and Sox18.

3.3. Sox7 conditional deletion in FLK1-expressing cells leads to severe defects in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis

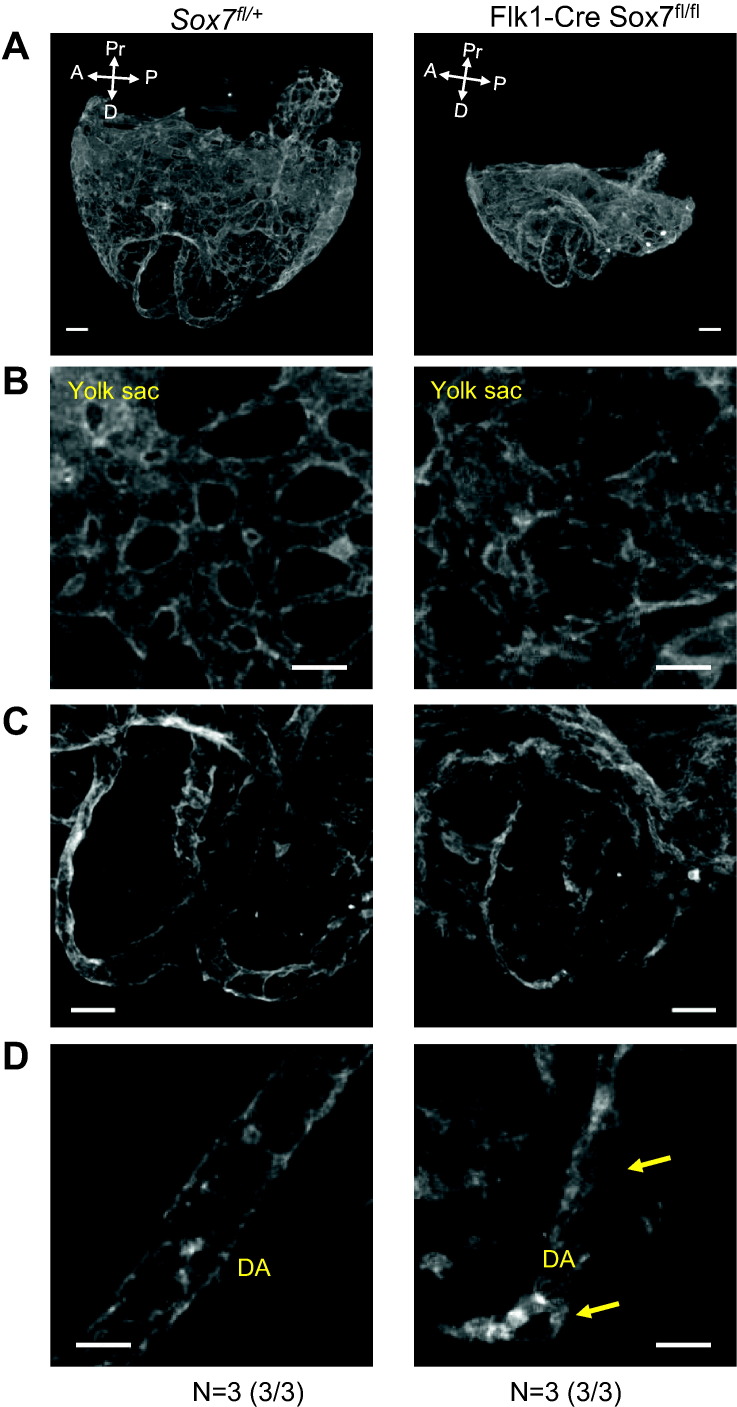

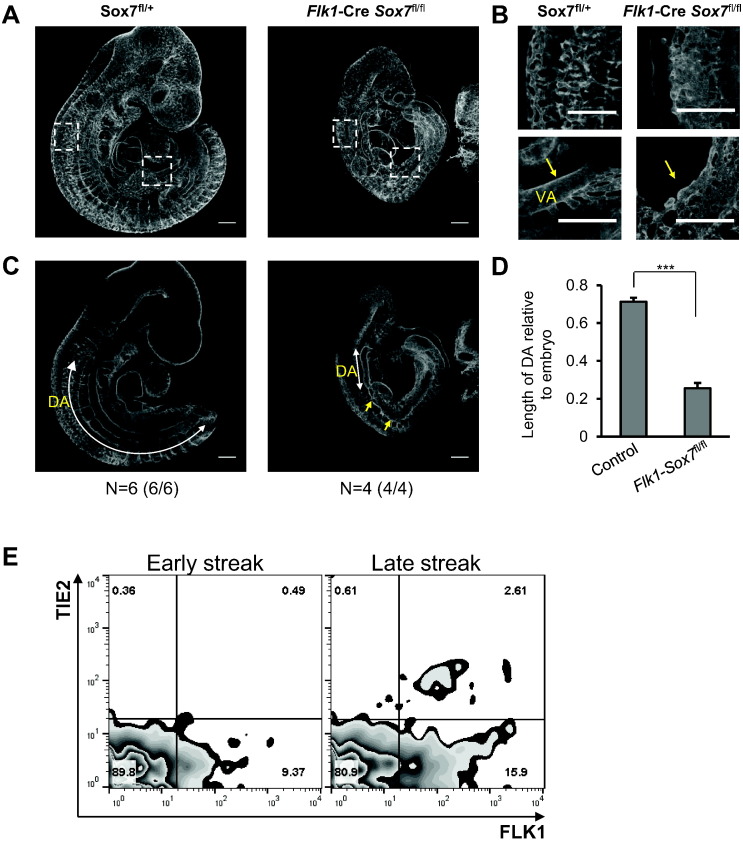

In addition to its expression in endothelial progenitors, Sox7 has been previously detected in primitive endoderm (Futaki et al., 2004, Murakami et al., 2004), in the earliest specified hematopoietic progenitors (Gandillet et al., 2009) and in emerging hematopoietic clusters in the dorsal aorta (Lilly et al., 2016, Nobuhisa et al., 2014). To define a possible role and requirement for Sox7 in specific compartments, we generated a Sox7 conditional allele in which the exon 2 of Sox7 is flanked by LoxP sequences and can be excised upon CRE expression. First, we analysed the requirement for Sox7 expression in the vascular compartment using a Flk1-cre transgenic mouse line (Motoike et al., 2003). The conditional deletion of Sox7 in FLK1-expressing cells resulted in early embryonic lethality and a phenotype very similar to the complete Sox7 knockout embryos. At E8.5, whole mount PECAM1 staining revealed that Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos displayed already noticeable defects in the developing vascular networks (Fig. 6A–D) including a disorganized yolk sac vascular plexus (Fig. 6B) and areas of highly unorganised endothelial cords in the posterior region of the dorsal aorta (Fig. 6C–D, yellow arrows). By E10.5, the highly unorganised nature of the vascular networks was indicative of considerable angiogenic defects resulting from the deletion of Sox7 in FLK1-expresssing cells (Fig. 7A) in agreement with the recently published phenotype of the Tie2 specific Sox7 knockout embryos (Kim et al., 2016) that was performed on homogenous genetic background unlike the study by Zhou and collaborators (Zhou et al., 2015). In contrast to Tie2-specific Sox7 deletion, the endothelial Flk1-specific deletion of Sox7 revealed marked defects in the formation of the major blood vessels in the embryo indicative of vasculogenic defects. In Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos, there was a lack of an observable vitelline artery in the embryo proper (Fig. 7B, yellow arrows). Furthermore, the functional dorsal aorta in Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos was extremely short, with the posterior region of the dorsal aorta resembling a cord of endothelial cells suggesting major defects in the vasculogenic events leading to the formation and organization of the angioblast cords giving rise to the posterior region of the dorsal aorta (Fig. 7C–D, white arrows). The lack of vitelline artery is most likely a direct consequence of the absence of the posterior dorsal aorta as the vitelline artery arises from the dorsal aorta (Drake and Fleming, 2000). It is likely that the differences between the Sox7 Tie2-deleted and Flk1-deleted embryonic phenotypes results from the earlier expression of FLK1 during development (Fig. 7E) and therefore the earlier deletion of Sox7 in Flk1-cre than in Tie2-cre embryos. Unlike Tie2, the expression of Flk1 is detected in mesoderm and mesenchyme (Ema et al., 2006), it is possible that Sox7 deletion in these tissues contributes to the stronger phenotype observed. These findings demonstrate that the expression of SOX7 is required earlier than previously described (Kim et al., 2016) and that SOX7 is an important transcriptional regulator of vasculogenesis.

Fig. 6.

Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos have defects in the dorsal aorta at E8.5. Whole mount PECAM1 staining of control (Sox7fl/+) and Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos and yolk sac at E8.5 (5–7 somite pairs). (A) 3D projection of embryos embedded within their yolk sacs, white arrows indicated anterior (A), posterior (P), distal (D) and proximal (Pr) axes. (B) Details of the yolk sac vasculature. (C) Paired dorsal aorta region. (D) Magnified view of a posterior region of a single dorsal aorta. Yellow arrows indicate malformation in the dorsal aorta. Scale bars 100 μm (A and C), 50 μm (B and D). Data are representative of at least three embryos with 100% penetrance of the phenotype observed for knockout embryos.

Fig. 7.

Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos have severe and widespread vascular defects at E10.5. Whole mount PECAM1 staining of Sox7fl/+ and Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos at E10.5. (A) 3D projection of embryo proper, white boxes indicate areas of magnification. Data shown are representative of 4 embryos. (B) Top panel: organization of capillaries in posterior region, bottom panel: vitelline artery (VA). (C) Sagittal slices through the embryo proper. DA: dorsal aorta, white arrow indicates length of functional dorsal aorta; yellow arrows indicate malformation of the DA. (D) Mean length of DA relative to embryo ± SEM, n = 6 control (Sox7fl/+ and Sox7fl/fl) versus n = 4 Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos. (E) Expression of FLK1 and TIE2 in wild type gastrulating embryos at early streak (left panel) and late streak (right panel) stages measured by flow cytometry.

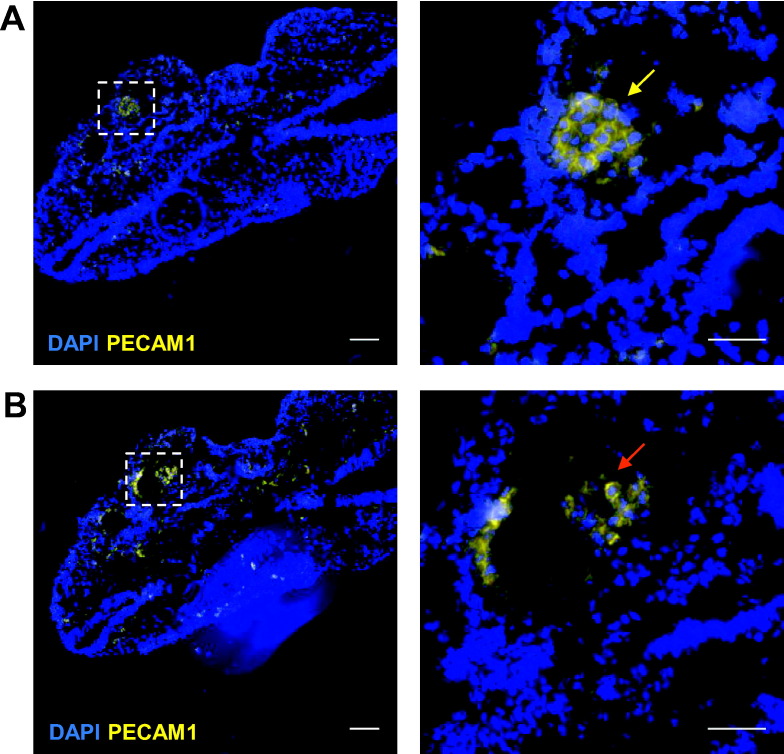

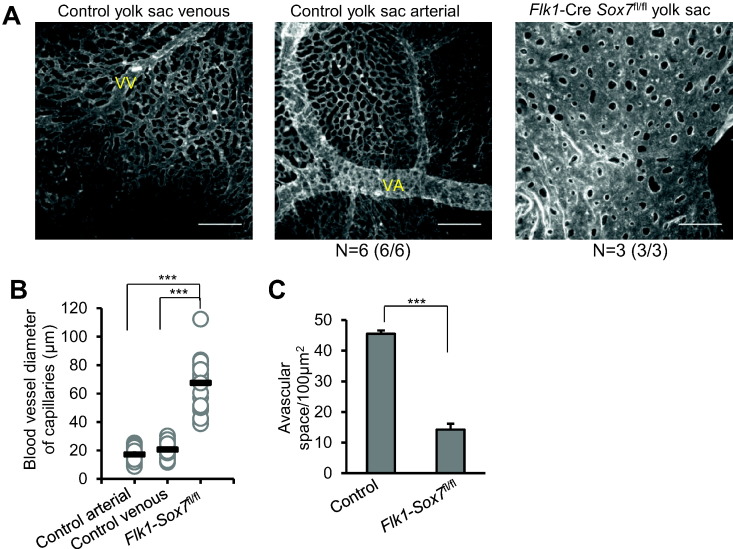

To further analyse the vascular defects in Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos, we performed PECAM1 staining on sections of E9.5 embryos (Fig. 8A and B). The complete disorganisation of the vascular network made comparisons of specific blood vessels with control embryos impossible. However, there was clear evidence of lumenization defects in a major blood vessel, as a mass of disorganized endothelial cells was observed (Fig. 8A, yellow arrow) that in the subsequent section formed a blood vessel with a lumen (Fig. 8B, red arrow). At E10.5 the yolk sac vasculature of Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos was arrested at a primitive vascular plexus stage, with a complete absence of vascular remodelling (Fig. 9A). In control yolk sacs, venous and arterial areas were easily identified along with the vitelline vein (VV) and vitelline artery (VA); in contrast the yolk sac of Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos only contained a homogenous plexus of vessels with relatively large diameters as shown by blood vessel diameter measurement (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, measurement of the space between capillaries identified that Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl plexuses have a decreased avascular space compared to capillaries of control yolk sacs (Fig. 9C). This is in contrast to embryos with hemodynamic flow deficiencies which show larger avascular space between non-remodelled yolk sac plexus blood vessels when compared to control embryos (Jones et al., 2008). Together, this suggests that the phenotype of the Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos is largely endothelial based and not due to cardiac defects causing decreased blood flow. Taken together, these data demonstrate that SOX7 is critically required in FLK1-expressing cells for both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. In particular, SOX7 seems to be critical for the formation of a fully lumenized dorsal aorta, suggestive of an incomplete circulatory loop: a phenotype similar to that of SOX7−/− zebrafish (Hermkens et al., 2015). However, unlike the zebrafish model, SOX7 deficiency in the mouse embryo also results in angiogenesis defects as demonstrated by the absence of remodelling and unorganised patterning of the entire vascular network.

Fig. 8.

Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos have lumenization defects in blood vessels. (A-B) PECAM1 staining of E9.5 Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryo sections. Left panels: 10 × objective, scale bars: 100 μm; right panels: 40 × objective, scale bars: 50 μm. Boxes denote areas of magnification. Top and bottom panels are two subsequent sections of the embryo. Yellow arrow: nonlumenized section of a blood vessel, red arrow: lumenized section of the same blood vessel.

Fig. 9.

Complete absence of remodelling in the yolk sac of Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl embryos. (A) Flat mounted E10.5 yolk sacs stained for PECAM1. Control yolk sacs have venous and arterial systems and large blood vessels such as a vitelline vein (VV) and a vitelline artery (VA). Data shown are representative of 3 embryos. (B) Diameter of capillaries in a control yolk sac (Sox7fl/+), compared with a Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl yolk sac. Data are presented as mean diameter (black bar), n = 30 capillaries. (C) Avascular space of capillaries/100μm2 in control versus Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl yolk sacs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6 control and n = 3 Flk1-Cre Sox7fl/fl yolk sacs. All statistical analyses are Student's two-tailed t-test. Scale bars = 500 μm.

The conditional deletion of Sox17 in TIE2-expressing cells also resulted in 100% embryonic lethality by E12.5 with major alterations in vascular remodelling, in the development of large arteries and in sprouting angiogenesis (Corada et al., 2013, Lee et al., 2014). Sox17 was also implicated in the acquisition and maintenance of arterial identity (Corada et al., 2013), while this role was shown to be performed by Sox7 in Zebrafish (Hermkens et al., 2015). It should be noted however that in Zebrafish Sox17 lacks the β-catenin binding domain which might explain these differences between mouse and zebrafish models (Chung et al., 2011). Together, these data suggested that both Sox7 and Sox17 are essential for the development of the vascular system and that they cannot compensate for each other, at least on homogeneous genetic background, and that they have slightly different roles in vasculogenesis and arterial specification, in line with their distinctive pattern of expression (Zhou et al., 2015).

Our findings also establish that while SOX7 is expressed in primitive endoderm (Murakami et al., 2004, Niimi et al., 2004), SOX7 is dispensable for the formation, maintenance or function of this lineage. Indeed, we observed an identical phenotype in Sox7 complete knockout embryos in which Sox7 is deleted in primitive endoderm and FLK1-specific Sox7 deficient embryos in which Sox7 is not deleted in primitive endoderm. Together this suggests that SOX7 deficiency in primitive endoderm in the complete knockout does not affect the early steps of embryonic development in which primitive endoderm plays a critical role in body plan formation and tissue induction (Stern and Downs, 2012). It is possible however that in Sox7 complete knockout embryos SOX17 compensates for SOX7 loss in primitive endoderm since SOX17 is also expressed in this lineage (Engert et al., 2009, Niimi et al., 2004). The generation of Sox7 and Sox17 double knockout embryos would be required to address the specific role of SOXF factors in primitive endoderm formation and function.

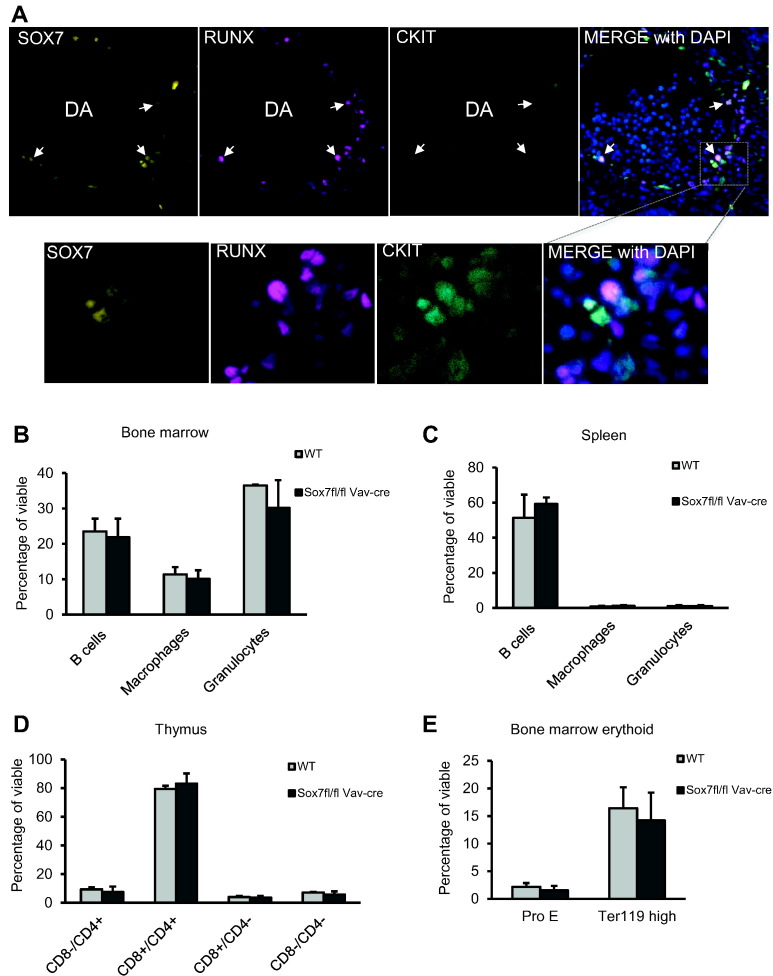

3.4. Sox7 conditional deletion in VAV-expressing cells does not affect the hematopoietic system

Finally, we analysed the consequence of the specific deletion of Sox7 in the hematopoietic compartment given the observed expression of SOX7 at all sites of hematopoietic emergence during embryogenesis (Lilly et al., 2016). Indeed, this was further confirmed by the co-expression of SOX7 with RUNX and cKIT, both marking emerging blood cells in the ventral aspect of the dorsal aorta in wild type embryos at E10.5 (Fig. 10A). To determine a possible role of SOX7 in hematopoiesis, Sox7fl/fl mice were crossed with Vav-Cre transgenic mice (de Boer et al., 2003), which resulted in Sox7 deficiency in all definitive hematopoietic cells. Interestingly, Vav-Cre Sox7fl/fl pups were viable and lived to adulthood without any phenotypic abnormalities or observable defects in the hematopoietic system (Fig. 10B–E). These data demonstrate that while Sox7 is expressed in the earliest blood progenitors, this transcription factor is not required for definitive hematopoiesis which encompasses all blood cells generated from E8.5 onward, including hematopoietic stem cells. However, it remains possible that the two other SOXF factors are providing enough compensation to allow for the emergence of blood cells in developing embryos deficient for Sox7 expression in Vav-expressing cells. The generation of triple SoxF conditional embryos would be required to address this possibility.

Fig. 10.

Vav-Cre Sox7fl/fl mice live to adulthood and have no hematopoietic defects. (A) Immuno-staining of E10.5 wild embryo transversal section. White arrows indicate example of cells co-expressing SOX7, RUNX and cKIT. Upper panels are 40 × magnification; lower panels are 100 × magnification. DA: dorsal aorta. (B and E) Bone marrow, (C) spleen and (D) thymus harvested from aged matched adult WT and Vav-Cre Sox7fl/fl mice and analysed by flow cytometry, gating first on the viable cells. B cells: CD19+ and/or B220+; macrophages: CD11b+ and F4/80+; granulocytes: CD11b+ and GR1+; Pro erythroblast (Pro E): Ter119med and CD71+; maturing erythroid cells: Ter119high. Data are presented as mean ± SE, n = 3 mice in each group. No differences were observed between WT and Vav-Cre Sox7fl/fl populations (Student's paired two-tailed t-test).

4. Concluding remark

The development of new vascular networks via vasculogenesis and angiogenesis is an important factor in the pathophysiology of all solid tumours. Neoplastic vascularisation facilitates the proliferation and subsequent metastasis of tumour cells, making angiogenic processes attractive targets in combating cancer (Nishida et al., 2006). The role of SOX7 in promoting tumour progression and angiogenesis is poorly understood. Recent data suggest that SOX17 is an important regulator of tumour angiogenesis (Yang et al., 2013). Together, these findings warrant further investigation into whether SOXF factors act redundantly or compensate for each other to promote tumour angiogenesis, which may offer novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of cancer.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Sox7−/− embryos have defects in the dorsal aorta at E8.5. Whole mount PECAM1 staining of E8.5 Sox7+/− and Sox7−/− embryos. Arrows indicate posterior section of dorsal aorta.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Flow Cytometry, Advanced Imaging and Molecular Biology Core facilities of CRUK Manchester Institute for technical support. Research in the authors’ laboratory is supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/P000673/1), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/I001794/1) and Cancer Research UK (C5759/A20971).

Contributor Information

Georges Lacaud, Email: georges.lacaud@cruk.manchester.ac.uk.

Valerie Kouskoff, Email: valerie.kouskoff@manchester.ac.uk.

References

- de Boer J., Williams A., Skavdis G., Harker N., Coles M., Tolaini M., Norton T., Williams K., Roderick K., Potocnik A.J., Kioussis D. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:314–325. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M.I., Ma A.C., Fung T.K., Leung A.Y. Characterization of Sry-related HMG box group F genes in zebrafish hematopoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 2011;39(986–998) doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corada M., Orsenigo F., Morini M.F., Pitulescu M.E., Bhat G., Nyqvist D., Breviario F., Conti V., Briot A., Iruela-Arispe M.L., Adams R.H., Dejana E. Sox17 is indispensable for acquisition and maintenance of arterial identity. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2609. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Val S., Black B.L. Transcriptional control of endothelial cell development. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:180–195. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake C.J., Fleming P.A. Vasculogenesis in the day 6.5 to 9.5 mouse embryo. Blood. 2000;95:1671–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M., Takahashi S., Rossant J. Deletion of the selection cassette, but not cis-acting elements, in targeted Flk1-lacZ allele reveals Flk1 expression in multipotent mesodermal progenitors. Blood. 2006;107:111–117. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert S., Liao W.P., Burtscher I., Lickert H. Sox17-2A-iCre: a knock-in mouse line expressing Cre recombinase in endoderm and vascular endothelial cells. Genesis. 2009;47:603–610. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehling H.J., Lacaud G., Kubo A., Kennedy M., Robertson S., Keller G., Kouskoff V. Tracking mesoderm induction and its specification to the hemangioblast during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Development. 2003;130:4217–4227. doi: 10.1242/dev.00589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferkowicz M.J., Yoder M.C. Blood island formation: longstanding observations and modern interpretations. Exp. Hematol. 2005;33:1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame J.M., Fegan K.H., Conway S.J., McGrath K.E., Palis J. Definitive hematopoiesis in the yolk sac emerges from Wnt-responsive hemogenic endothelium independently of circulation and arterial identity. Stem Cells. 2016;34:431–444. doi: 10.1002/stem.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois M., Caprini A., Hosking B., Orsenigo F., Wilhelm D., Browne C., Paavonen K., Karnezis T., Shayan R., Downes M., Davidson T., Tutt D., Cheah K.S., Stacker S.A., Muscat G.E., Achen M.G., Dejana E., Koopman P. Sox18 induces development of the lymphatic vasculature in mice. Nature. 2008;456:643–647. doi: 10.1038/nature07391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois M., Koopman P., Beltrame M. SoxF genes: key players in the development of the cardio-vascular system. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010;42:445–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futaki S., Hayashi Y., Emoto T., Weber C.N., Sekiguchi K. Sox7 plays crucial roles in parietal endoderm differentiation in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells through regulating Gata-4 and Gata-6 expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:10492–10503. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10492-10503.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandillet A., Serrano A.G., Pearson S., Lie A.L.M., Lacaud G., Kouskoff V. Sox7-sustained expression alters the balance between proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors at the onset of blood specification. Blood. 2009;114:4813–4822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-226290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert S.P., Stainier D.Y. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:551–564. doi: 10.1038/nrm3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermkens D.M., van Impel A., Urasaki A., Bussmann J., Duckers H.J., Schulte-Merker S. Sox7 controls arterial specification in conjunction with hey2 and efnb2 function. Development. 2015;142:1695–1704. doi: 10.1242/dev.117275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking B., Francois M., Wilhelm D., Orsenigo F., Caprini A., Svingen T., Tutt D., Davidson T., Browne C., Dejana E., Koopman P. Sox7 and Sox17 are strain-specific modifiers of the lymphangiogenic defects caused by Sox18 dysfunction in mice. Development. 2009;136:2385–2391. doi: 10.1242/dev.034827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E.A., Yuan L., Breant C., Watts R.J., Eichmann A. Separating genetic and hemodynamic defects in neuropilin 1 knockout embryos. Development. 2008;135:2479–2488. doi: 10.1242/dev.014902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai-Azuma M., Kanai Y., Gad J.M., Tajima Y., Taya C., Kurohmaru M., Sanai Y., Yonekawa H., Yazaki K., Tam P.P., Hayashi Y. Depletion of definitive gut endoderm in Sox17-null mutant mice. Development. 2002;129:2367–2379. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I., Saunders T.L., Morrison S.J. Sox17 dependence distinguishes the transcriptional regulation of fetal from adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2007;130:470–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Kim I.K., Yang J.M., Lee E., Koh B.I., Song S., Park J., Lee S., Choi C., Kim J.W., Kubota Y., Koh G.Y., Kim I. SoxF transcription factors are positive feedback regulators of VEGF signaling. Circ. Res. 2016;119:839–852. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancrin C., Sroczynska P., Stephenson C., Allen T., Kouskoff V., Lacaud G. The haemangioblast generates haematopoietic cells through a haemogenic endothelium stage. Nature. 2009;457:892–895. doi: 10.1038/nature07679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.H., Lee S., Yang H., Song S., Kim K., Saunders T.L., Yoon J.K., Koh G.Y., Kim I. Notch pathway targets proangiogenic regulator Sox17 to restrict angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2014;115:215–226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly A.J., Costa G., Largeot A., Fadlullah M.Z., Lie A.L.M., Lacaud G., Kouskoff V. Interplay between SOX7 and RUNX1 regulates hemogenic endothelial fate in the yolk sac. Development. 2016;143:4341–4351. doi: 10.1242/dev.140970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly A.J., Lacaud G., Kouskoff V. SOXF transcription factors in cardiovascular development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017;63:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Kanai-Azuma M., Hara K., Matoba S., Hiramatsu R., Kawakami H., Kurohmaru M., Koopman P., Kanai Y. Redundant roles of Sox17 and Sox18 in postnatal angiogenesis in mice. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:3513–3526. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoike T., Markham D.W., Rossant J., Sato T.N. Evidence for novel fate of Flk1 + progenitor: contribution to muscle lineage. Genesis. 2003;35:153–159. doi: 10.1002/gene.10175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami A., Shen H., Ishida S., Dickson C. SOX7 and GATA-4 are competitive activators of Fgf-3 transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:28564–28573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimi T., Hayashi Y., Futaki S., Sekiguchi K. SOX7 and SOX17 regulate the parietal endoderm-specific enhancer activity of mouse laminin alpha1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:38055–38061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida N., Yano H., Nishida T., Kamura T., Kojiro M. Angiogenesis in cancer. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2006;2:213–219. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobuhisa I., Osawa M., Uemura M., Kishikawa Y., Anani M., Harada K., Takagi H., Saito K., Kanai-Azuma M., Kanai Y., Iwama A., Taga T. Sox17-mediated maintenance of fetal intra-aortic hematopoietic cell clusters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:1976–1990. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01485-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risau W., Flamme I. Vasculogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1995;11:73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y. Dorsal aorta formation: separate origins, lateral-to-medial migration, and remodeling. Develop. Growth Differ. 2013;55:113–129. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers G.E., Teasdale R.D., Koopman P. Twenty pairs of sox: extent, homology, and nomenclature of the mouse and human sox transcription factor gene families. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn J., Natale J., Chew L.J., Belachew S., Cheng Y., Aguirre A., Lytle J., Nait-Oumesmar B., Kerninon C., Kanai-Azuma M., Kanai Y., Gallo V. Identification of Sox17 as a transcription factor that regulates oligodendrocyte development. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:9722–9735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1716-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroczynska P., Lancrin C., Pearson S., Kouskoff V., Lacaud G. In vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells as a model of early hematopoietic development. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;538:317–334. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-418-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern C.D., Downs K.M. The hypoblast (visceral endoderm): an evo-devo perspective. Development. 2012;139:1059–1069. doi: 10.1242/dev.070730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takash W., Canizares J., Bonneaud N., Poulat F., Mattei M.G., Jay P., Berta P. SOX7 transcription factor: sequence, chromosomal localisation, expression, transactivation and interference with Wnt signalling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4274–4283. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thambyrajah R., Mazan M., Patel R., Moignard V., Stefanska M., Marinopoulou E., Li Y., Lancrin C., Clapes T., Moroy T., Robin C., Miller C., Cowley S., Gottgens B., Kouskoff V., Lacaud G. GFI1 proteins orchestrate the emergence of haematopoietic stem cells through recruitment of LSD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:21–32. doi: 10.1038/ncb3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wat M.J., Beck T.F., Hernandez-Garcia A., Yu Z., Veenma D., Garcia M., Holder A.M., Wat J.J., Chen Y., Mohila C.A., Lally K.P., Dickinson M., Tibboel D., de Klein A., Lee B., Scott D.A. Mouse model reveals the role of SOX7 in the development of congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with recurrent deletions of 8p23.1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:4115–4125. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Lee S., Lee S., Kim K., Yang Y., Kim J.H., Adams R.H., Wells J.M., Morrison S.J., Koh G.Y., Kim I. Sox17 promotes tumor angiogenesis and destabilizes tumor vessels in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:418–431. doi: 10.1172/JCI64547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokomizo T., Yamada-Inagawa T., Yzaguirre A.D., Chen M.J., Speck N.A., Dzierzak E. Whole-mount three-dimensional imaging of internally localized immunostained cells within mouse embryos. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:421–431. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Williams J., Smallwood P.M., Nathans J. Sox7, Sox17, and Sox18 cooperatively regulate vascular development in the mouse retina. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sox7−/− embryos have defects in the dorsal aorta at E8.5. Whole mount PECAM1 staining of E8.5 Sox7+/− and Sox7−/− embryos. Arrows indicate posterior section of dorsal aorta.