Abstract

Background

Resistive breathing practices are known to improve endurance and performance in competitive swimmers. However, the effect of Pranayama or Yogic Breathing Practices (YBP) in improving respiratory endurance and performance of competitive swimmers remains un-investigated.

Objectives

To study effects of yogic breathing practices on lung functions of swimmers.

Material and methods

Twenty seven national and international competitive swimmers of the age range 13–20 years, with 8.29 ± 2.9 years of competitive swimming experience and practicing swimming for 9.58 ± 1.81 km everyday, were assigned randomly to either an experimental (YBP) or to wait list control group (no intervention). Outcome measures were taken on day 1 and day 30 and included (1) spirometry to measure lung function, (2) Sport Anxiety Scale-2 (SAS-2) to measure the antecedents and consequences of cognitive and somatic trait anxiety of sport performance and (3) number of strokes per breath to measure performance. The YBP group practiced a prescribed set of Yogic Breathing Practices – Sectional Breathing (Vibhagiya Pranayama), Yogic Bellows Breathing (Bhastrika Pranayama) and Alternate Nostril Breathing with Voluntary Internal Breath Holding (Nadi Shodhana with Anthar kumbhaka) for half an hour, five days a week for one month.

Results

There was a significant improvement in the YBP group as compared to control group in maximal voluntary ventilation (p = 0.038), forced vital capacity (p = 0.026) and number of strokes per breath (p = 0.001).

Conclusion

The findings suggest that YBP helps to enhance respiratory endurance in competitive swimmers.

Keywords: Pranayama, Breathing practices, Competitive swimming, Pulmonary function

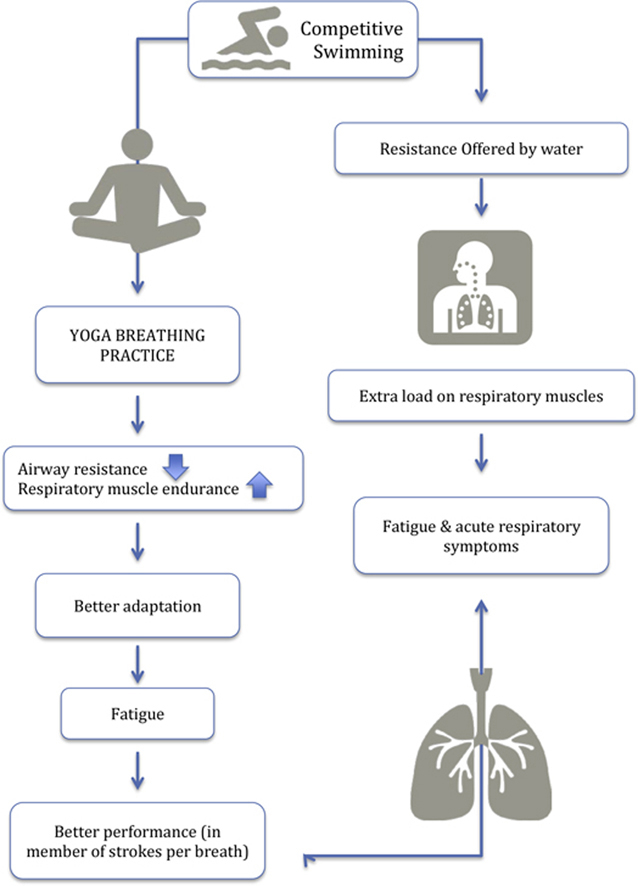

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Swimming as a competitive sport involves propelling one's body in water by pushing against it. The water, because of its greater density, offers more resistance to the swimmers than air in land based sports [1]. Competitive swimmers are expected to have specific anthropometrical features compared to other athletes [2]. Swimming being an activity that requires physical strength and endurance, is often associated with large lung volumes and relatively reduced flow, which may represent a physiological variant of normal pulmonary functions but also can signify an obstructive abnormality [3]. Increased respiratory work in competitive swimming induces respiratory muscle fatigue and in turn reduces swimming endurance, performance and breathing frequency [4], [5]. Evidence suggests that serum lactate, a metabolic by product of the glycolytic pathway increases in swimming and contributes to stiffness and soreness [6]. Increased serum lactate levels have been shown to influence stroke rate and distance covered per stroke while swimming [7].

The conventional method used for competitive swimming is inhaling through the mouth in a short time and exhaling the air from the nose while underwater [8], [9], thereby reducing the resistance caused by turning the head [10]. However, due to an increase in exhalation, which helps in overcoming the resistance of water, there is a resultant increase in the fatigue of the respiratory muscles [11] and reduction in blood flow and oxygen supply to other exercising muscles [3].

In competitive swimming, strict regulation of breathing is essential [12] to ensure maximum levels of oxygen in a relatively available short time span [13]. Techniques evolved to enhance performance and to overcome the associated complications of swimming had focused on keeping well-conditioned lungs, increasing the vital capacity, regulating breathing pattern and strengthening respiratory musculature [4].

Research has indicated the influence of somatic and cognitive anxiety on outcome measures in sports. The process of competitive stress involves the perception of a substantial imbalance between the environmental demand and one's response capabilities. This imbalance is perceived as having important consequences on the outcome [14]. Elevation in sympathetic tone as marked by anxiety and reduced Heart Rate Variability patterns have been shown to be regulated by regulation of breathing [15]. Also, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) aimed towards reducing anxiety has been documented to increase performance [16]. The ability to overcome pressure and anxiety is an integral part of sports, particularly among elite athletes [17], [18].

Pranayama is more than a simple breathing exercise. It is not merely breath control but is one of the powerful yogic techniques used to regulate the flow of energy, ‘prana’ in the body to a higher frequency [19]. Traditional yogic literature suggest four important aspects of breathing utilized in Pranayama. They are Puraka or inhalation, Rechaka or exhalation, Anthar kumbhaka or Internal Breath Retention and Bahir kumbhaka or External Breath Retention [20]. In the current study three pranayama or Yogic Breathing Practices (YBP) have been utilized: Sectional Breathing (Vibhagiya Pranayama), Yogic Bellows Breathing (Bhastrika Pranayama) and Alternate Nostril Breathing with Voluntary Internal Breath Retention (Nadi Shodhana Pranayama with Anthar kumbhaka).

In healthy individuals, Alternate Nostril Breathing has been shown to be effective in improving vital capacity of the lungs as well as cardio-pulmonary functioning [11]. Alternate Nostril Breathing when practiced along with Yogic Bellows Breathing has been shown to improve Maximum Ventilatory Volume along with Vital Capacity of the lungs [21], whereas the same when practiced with Voluntary Internal Breath Retention ensures better oxygen availability to the tissues [21]. Yogic Bellows Breathing when practiced along with other breathing practices showed a better reduction in basal heart rate and respiratory rate suggesting a better cardiac autonomic reactivity and parasympathetic activity [22]. Sectional Breathing practices increased thoraco-pulmonary compliances by more efficient use of diaphragmatic and abdominal muscles, thereby emptying and filling the respiratory apparatus more efficiently and completely. Sectional Breathing involving individual's awareness helps correct the inefficient breathing pattern and increase Vital Capacity of lungs [23]. Having studied individually, the effects of the Yogic Breathing Practices in healthy volunteers, this study aims to utilize these practices to enhance pulmonary function and endurance of the respiratory muscles in competitive swimmers.

Based on the findings from the earlier studies, we hypothesized Alternate Nostril Breathing with Voluntary Internal Breath Retention; Yogic Bellows Breathing and Sectional Breathing are expected to alleviate sport anxiety through reduction of sympathetic arousal, enhance endurance of the respiratory muscles and vital capacity of the lungs thereby reducing fatigue and acute respiratory symptoms.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

Twenty seven competitive swimmers from a swimming academy, (thirteen males and fourteen females) of the age range 13–20 years, with 8.29 ± 2.9 years of competitive swimming experience, practicing swimming for 9.58 ± 1.81 km everyday, participated in the study. The project was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. A written informed consent was obtained from all the participants above 18 years and for minors below the age of 18 years an informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians.

The sample size was estimated from a previous study conducted with an effect size of 0.9 and an estimated sample size of 24. Considering drop outs more swimmers (n=30) were included in the study.

2.2. Experimental design: randomized matched control clinical study

Participants were first stratified according to their age and gender and randomly assigned into one of two, Yogic Breathing Practices (YBP) and wait-list control groups based on a computerized random number generator. Baseline characteristics of the participants in each group are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the initially randomized sample.

| Sl No | Baseline characteristics | YBP group n = 14 (Mean ± SD) | Control group n = 15 (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age (in years) | 15.23 ± 1.59 | 15.08 ± 1.26 |

| 2. | Height (in cm) | 165.69 ± 10.38 | 163.31 ± 10.28 |

| 3. | Weight (in kg) | 55 ± 9.66 | 52.77 ± 10.39 |

| 4. | Experience (in years) | 8.15 ± 2.96 | 8.42 ± 2.83 |

| 5. | Swimming per day (in km) | 9.62 ± 1.89 | 9.53 ± 1.81 |

| 6. | Swimming per week (in km) | 48.08 ± 9.47 | 47.69 ± 9.04 |

2.3. Experimental protocol

The YBP group was administered with Sectional Breathing (Vibhagiya Pranayama), Yogic Bellows Breathing (Bhastrika Pranayama) and Alternate Nostril Breathing (Nadi Shodhana) with Voluntary Internal Breath Retention (Anthar kumbhaka) for thirty minutes, five days a week for a period of one month along with their regular practice of swimming and physical training. The control group underwent only physical training practices (Table 2). The practice was administered in a sound attenuated hall as a pre-recorded audio to avoid instructor bias. However, the instructor was available throughout the practice session to clarify the doubts if any. The waitlist control group practiced their regular swimming and physical training protocol.

Table 2.

List of Yoga practices

| Practice | Duration |

|---|---|

| Regular physical training undertaken by both the groups | |

| Running and stretching exercises | 20 min |

| Endurance building exercises | 20 min |

| Swimming drills | 6 kick & 3 pull |

| Practices specific to yoga group | |

| Sectional Breathing | 10 min |

| Yogic Bellows Breathing (Bhastrika Pranayama) | 10 min |

| Alternate Nostril Breathing with Voluntary Internal Breath Retention | 10 min |

2.3.1. Description of intervention

2.3.1.1. Sectional Breathing (Vibhagiya Pranayama)

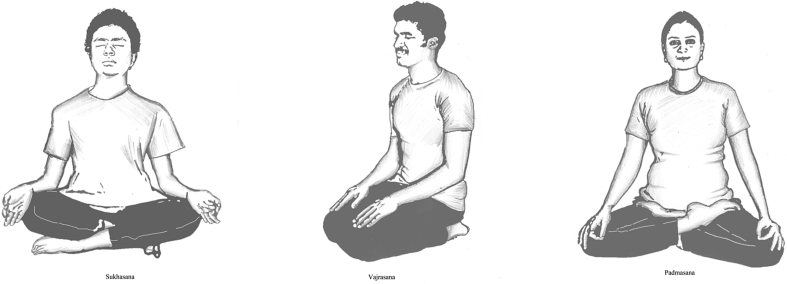

Sectional Breathing is a preparatory breathing practice for pranayama, which helps to correct the incorrect breathing pattern such as habitual over breathing, breath holding or shallow breathing. Participants were asked to sit in a comfortable posture – sukhasana, padmasana or vajarasana with the spine erect (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Representation of postures in which the pranayama practices were administered to Yoga group

Abdominal breathing: Instructions were given to inhale by bulging out the abdominal muscles and exhale by drawing back the abdomen inward. Thoracic breathing: Instructions were given to inhale by expanding the chest muscles and exhale by returning the chest to its normal position. This was repeated for 10 rounds.

Upper lobar breathing: Instructions were given to inhale raising the collar bones and shoulders upwards and backwards and exhale by dropping the shoulders into a resting position. This was repeated for 10 rounds.

Full yogic breathing: Instructions were given to inhale in the following sequence – Abdominal breathing, Thoracic breathing and Upper lobar breathing and exhale in the same sequence. This was practiced at a frequency of 4 breaths/min [20].

The steps mentioned above were repeated with awareness for 10 rounds. The entire practice was completed in a duration of 10 min.

2.3.1.2. Yogic Bellows Breathing (Bhastrika Pranayama)

Instructions were given to breathe in and out forcefully through the nose without straining any part of the body. They were asked to expand and contract abdomen rhythmically with the breath. This was done through the left nostril, then the right nostril and both the nostrils, which was repeated for ten rounds making one set. After each set there was retention of the breath for a twenty seconds. Then the participants were asked to breathe out slowly and return to normal breathing. This made one round of Yogic Bellows Breathing. The same procedure was repeated for 2 rounds followed by relaxation for 10 min in total [20].

2.3.1.3. Alternate Nostril Breathing with Voluntary Internal Breath Retention (Nadi Shodhana with Anthar kumbhaka)

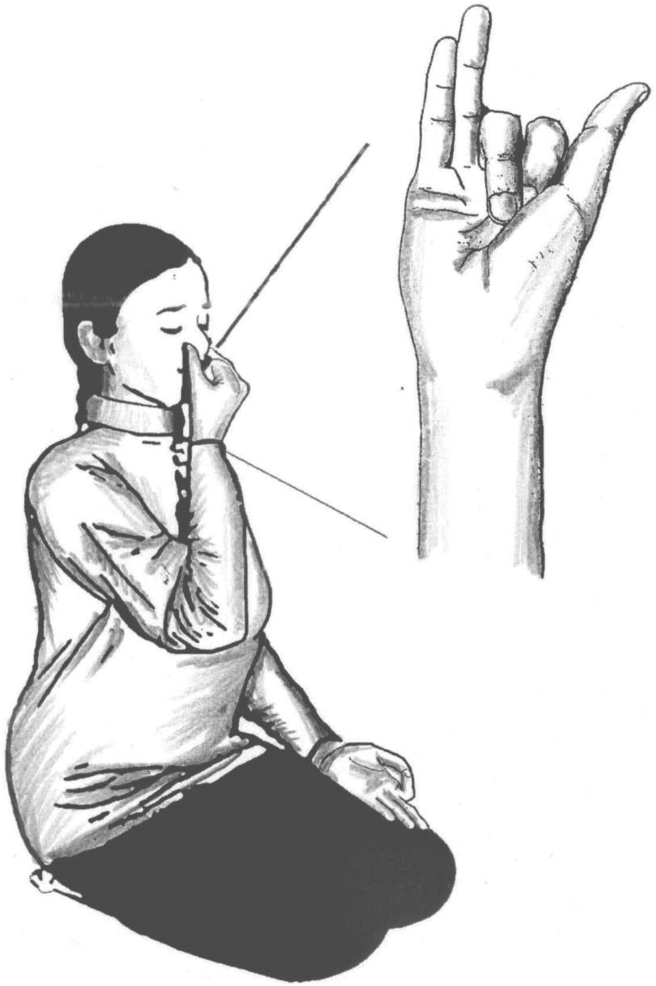

Instructions were given to adopt nasika mudra (Fig. 2). Following complete exhalation, participants were instructed to inhale through the left nostril closing the right nostril and hold the breath by closing both the nostrils and placing the chin close to the jugular notch. Following breath holding, raising the head, instruction was given to exhale through the right nostril while closing the left. Inhalation was then done through right nostril and exhalation through left nostril following breath holding to complete one round of Nadi Shodhana Pranayama with Kumbhaka. Inhalation, breath holding and exhalation were performed for a duration of 8 s each (ratio 1:1:1) amounting the respiratory rate to be 2.5 breaths/minute [24], [25]. Practice was repeated for a duration of 10 min.

Fig. 2.

Representation of Alternate Nostril Breathing performed with nasika mudra.

2.3.1.4. Outcome measures

The spirometery test was done as per the standardization protocol prescribed by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) [26]. Slow Vital Capacity (SVC), Inspiratory Reserve Volume (IRV), Forced Vital Capacity (FVC), Maximum Voluntary Ventilation (MVV) and Minute Ventilation (MV), and Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF) were determined for assessing lung functions in all participants on day 1 and day 30.

Sport Anxiety Scale – 2 (SAS-2) is an anxiety scale, measuring the antecedents and consequences of cognitive and somatic trait anxiety in children and adults in sport performance settings [27]. The SAS-2 has 30-items which measures individual differences in somatic anxiety and two aspects of cognitive anxiety, namely, worry and concentration disruption responded on a 4-point extent-of-experience scale containing the following scales: 1 (not at all), 2 (a little bit), 3 (pretty much) and 4 (very much). The participants were asked to fill the SAS-2 questionnaire on the day 1 and day 30.

The capacity of the competitive swimmer to efficiently prolong the breath and perform more strokes per breath shall play a significant role in increasing the speed of swimming. The participants were asked about their subjective observation of swimming strokes per breath on the day 1 and day 30 to assess their performance. This was done to understand the participant's subjective experience to their specific experimental conditions.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). Descriptive statistics were used to assess normality and homogeneity. Following normal distribution of the data, paired sample t test was used to assess the within group changes, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for between group changes were performed. Principal Component Analysis was performed for height, weight, duration of practice per week and experience of swimming. The component obtained and baseline values of the variables were used as covariates to determine the between-group changes following intervention.

3. Results

The mean age of the participants was 15.23 ± 1.59 in YBP group and 15.08 ± 1.26 in the waitlist control group. Attendance was maintained to estimate adherence. 90% adherence was considered as eligibility for the participants to be included in the study. However, in the study the adherence was 100% Participants in both the groups were comparable with respect to the socio-demographic characteristics.

3.1. Pulmonary functions

ANCOVA test showed a significant improvement in Maximum Voluntary Ventilation (MVV) (F(1,22) = 6.06, p = 0.02) and Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) (F(1,22) = 5.68. p = 0.026) between the groups following intervention. There were no significant differences observed in the Slow Vital Capacity (SVC), Inspiratory Reserve Volume (IRV), Minute Ventilation (MV) and Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of pulmonary function

| Sl No | Descriptive | YBP Group (Mean ± SD) n = 14 |

Control Group (Mean ± SD) n = 13 |

np2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| 1. | SVC | 3.13 ± 0.52 | 3.01 ± 0.59 | 2.95 ± 1.07 | 2.63 ± 0.71 | 0.112 |

| 2. | IRV | 1.19 ± 0.43 | 1.45 ± 0.76a | 1.01 ± 0.45 | 1.12 ± 0.46 | 0.044 |

| 3. | FVC | 2.91 ± 0.42 | 3.14 ± 1.03b | 2.52 ± 0.65 | 2.39 ± 0.75 | 0.205 |

| 4. | MVV | 106.5 ± 30.61 | 115.45 ± 31.44b | 102.98 ± 23.52 | 97.65 ± 20.37 | 0.216 |

| 5. | MV | 27.35 ± 11.95 | 23.04 ± 14.15 | 24.93 ± 21.03 | 17.78 ± 9.82 | 0.037 |

| 6. | PEF | 6.34 ± 1.13 | 6.84 ± 1.61 | 5.67 ± 1.47 | 5.45 ± 1.80 | 0.148 |

p ≤ 0.05 for within group analysis using paired t test.

p ≤ 0.05 for between group analysis using Analysis of Covariance.

3.2. Sport Anxiety Scale

Paired t test done to assess within group changes show a significant reduction in self-reported Total Sport Anxiety (t = 2.45, p = 0.031), Concentration Disruption (t = 2.635, p = 0.022) and Somatic Complaints (t = 2.343, p = 0.037) in the YBP group. No significant change was observed between the groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Sport Anxiety.

| S No | Description | YBP Group (Mean ± SD) n = 14 |

Waitlist Control Group (Mean ± SD) n = 13 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| 1. | Concentration disruption | 9.38 ± 2.18 | 8.0 ± 2.0a | 9.46 ± 2.63 | 9.15 ± 2.54 |

| 2. | Somatic complaints | 10.15 ± 3.62 | 8.62 ± 3.28a | 10.31 ± 2.46 | 10.08 ± 2.88 |

| 3. | Anxiety | 10.0 ± 2.71 | 8.85 ± 2.54 | 9.77 ± 2.49 | 9.46 ± 2.44 |

| 4. | Total score in SAS-2b | 29.54 ± 7.15 | 25.46 ± 6.73a | 29.54 ± 6.30 | 28.69 ± 6.64 |

p ≤ 0.05 for within group analysis using paired t test.

SAS-2 – Sport Anxiety Questionnaire -2.

3.3. Number of strokes

Paired t test done to assess the within group changes showed a significant increase in the number of strokes per breath in the YBP group (t = 7.98, p ≤ 0.001). Analysis of Variance on post-intervention measures showed a significant increase in the number of strokes per breath in the YBP group compared with controls (F(1,22) = 13.06, p = 0.002) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of total strokes per breath.

| S No | Description | YBP (Mean ± SD) n = 14 |

Control (Mean ± SD) n = 13 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| 1. | Total Strokes | 2.08 ± 0.76 | 3.54 ± 0.88a,b | 2.85 ± 0.9 | 3.08 ± 0.86 |

p values ≤ 0.001 for within group changes using paired t test.

p values ≤ 0.001 for between group changes using analysis of covariance.

4. Discussion

Thirty competitive swimmers of age range 15.27 ± 1.66 yrs, were randomly allocated to YBP or waitlist control groups. A significant change in Maximal Voluntary Ventilation, Forced vital capacity as well as in swimming performance based on number of strokes per breath were observed in YBP as compared to the controls following one month of intervention. There were 3 dropouts, 1 from the YBP group and 2 from the control group as the participants were not available for their post recordings. Posthoc analysis showed the effect size of the present study to be 0.69 indicating the findings of the study to have medium to large effect size.

These findings are in accordance with earlier findings suggestive of resistive breathing training improving the pulmonary functions [4].

The purpose of the study was to assess the role of the voluntary breath regulation practices in improving lung volumes, respiratory muscle endurance and decreasing sport anxiety. It is well established through previous studies that, following swimming practices, lung function of swimmers is reduced due to the pressure of water on thorax causing restriction [28], gradually leading to a state of end-organ fatigue at the level of diaphragm caused by reduced oxygen supply, increased anaerobic metabolism and accumulated lactic acid. In the present study, an observed increase in Maximal Voluntary Ventilation and Forced Vital Capacity can be attributed to the increased strength of the respiratory musculature [29].

The increase in number of strokes per breath in YBP group suggests an increase in breath holding time. However, this measure was used as a tool to understand the possible impact of YBP in improving the performance. Practice of voluntary breath retention involves voluntary cessation of breathing and slowing down the speed of breathing [4], aiding a practitioner to gain control over the pneumotaxic center and influencing the pontine areas on the brain stem. Control over these areas facilitates the practitioner to prolong the breath holding time following inspiration [30]. Also, YBP have shown beneficial effects in improving oxygen carrying capacity of RBCs [31], which is reduced with increasing stress and anxiety. Pranayama practices cleanses airway secretions and acts as a major physiological stimulus for release of lung surfactant and prostaglandins into alveolar spaces and promote lung compliance [32]. Even though, breath holding induces transient phases of hypoxia [33], Pranayama practices are expected to deliver the results through promoting the production of lung surfactants [32], reduce the surface tension and promote exchange of gases in alveolar membrane and enhancing the oxygen carrying capacity of the RBCs [31].

An increase in MVV and FVC is associated with decreased resistance of airways and increased strength of the respiratory musculature [34], [35]. However, the present study has not made attempts to understand the role of YBP in maintaining the airway patency. The present results are suggestive of increased endurance of the pulmonary musculature, better oxygen availability and possible reduction in end organ fatigue through increased MVV and reduction in concentration disruption, somatic stress and worry as indicated by the Sport Anxiety Scale-2.

However earlier studies on exercise training suggest that, there occurs no change to the Basal Metabolic Rate irrespective of the pulmonary capacity [36] but, Yoga practices have shown reduction in Basal Metabolic Rate [37], which might be of importance to be explored as a reason for increased efficiency.

No significant differences were observed between the genders in both the groups. Age-based comparison of outcomes were not performed owing to the less sample size. The present study has not been designed to monitor progressive improvement in the lung capacities. The limitation of this study is that it does not give us an understanding of the duration or the point of time at which, the beneficial effects become observable. Further research is required to understand the physiological adaptations that might have taken place in the respiratory musculature and the group that is most benefitted by the Yogic Breathing Practices.

5. Conclusion

The findings of the present study are in accordance with earlier findings suggestive of resistive breathing training enhancing pulmonary capacities. The results suggest that YBP for 30 min a day along with routine physical exercises for five days a week, decreases airway resistance, increases respiratory muscle endurance, and number of strokes per breath, possibly, through better autonomic reactivity, oxygen diffusion and reduced anxiety in competetive swimmers. Future studies are required to understand the actual adaptations in the respiratory muscles and improvements in performance.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Romer L.E., Polkey M.I. Exercise-induced respiratory muscle fatigue: implications for performance. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(3):879–888. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01157.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aspenes S.T., Karlsen T. Exercise-training intervention studies in competitive swimming. Sports Med. 2012;42(6):527–543. doi: 10.2165/11630760-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silvestri M., Crimi E., Oliva S., Senarega D., Tosca M.A., Rossi G.A. Pulmonary function and airway responsiveness in young competitive swimmers. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48(1):74–80. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindholm P., Wylegala J., Pendergast D.R., Lundgren C.E.G. Resistive respiratory muscle training improves and maintains endurance swimming performance in divers. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2007;34(3):169–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lomax M., Castle S. Inspiratory muscle fatigue significantly affects breathing frequency, stroke rate, and stroke length during 200-m front-crawl swimming. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(10):2691–2695. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318207ead8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung K., Hume P., Maxwell L. Delayed onset muscle soreness: treatment strategies and performance factors. Sports Med. 2003;33(2):145–164. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveira M.F., Caputo F., Dekerle J., Denadai B., Greco C. Stroking parameters during continuous and intermittent exercise in regional-level competitive swimmers. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(9):696–701. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong S.K., Cerretelli P., Cruz J.C. Mechanics of respiration during submersion in water. J Appl Physiol. 1969;27(4):535–538. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.27.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer J. 2010. Greaing up. Simple swimming guide; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maglischo E.W. 2003. Reducing resistance. Swimming fastest: the essential reference on technique, training, and program design; pp. 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S., Gaurav V., Parkash V. Effects of a 6-week nadi-shodhana pranayama training on cardio-pulmonary parameters. J Phys Educ Sport Manag. 2010;2(4):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilding A.E., Brown S., McConnell A.K. Inspiratory muscle training improves 100 and 200 m swimming performance. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(3):505–611. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgic B., Puletic M., Okicic T., Meškovska N. Importance of maximal oxygen consumption during swimming. Phys Educ Sport. 2011;9(2):183–219. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martens R., Vealey R.S., Burton D. Human Kinetics; 1990. Competitive anxiety in sport. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown R.P., Gerbarg P.L. Sudarshan Kriya yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression: part I-neurophysiologic model. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(1):189–201. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miguel-Humara M.A. The relationship between anxiety and performance: a cognitive-behavioral perspective. Online J Sport Psychol. 1999;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy L., Jones G., Gould D. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 1996. Understanding psychological preparation for sport: theory and practice of elite performers. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlick T., Partington J. Mental links to excellence. Sport Psychol. 1988;2:105–130. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muktibodhananda S., Saraswati S.S. Yoga publication trust; Munger, Bihar: 2009. Hatha yoga pradipika. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saraswati S.S. Yoga publication trust; Munger, Bihar: 2002. Asana pranayama mudra bandha. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bal B.S. Effect of anulom vilom and bhastrika pranayama on the vital capacity and maximal ventilatory volume. J Phys Educ Sport Manag. 2010;1(1):11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veerabhadrappa S.G., Herur A., Patil S., Ankad R.B., Chinagudi S., Baljoshi V.S. Effect of yogic bellows on cardiovascular autonomic reactivity. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2011;2(4):223–227. doi: 10.4103/0975-3583.89806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagarathana R., Nagendra H.R. Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana; Bangalore: 2010. Yoga for promotion of positive health. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyengar B.K.S. 1st ed. Element; Pune: 2005. Light on pranayama; p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telles S., Desiraju T. Oxygen consumption during pranayamic type of very slow-rate breathing. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller M.R., Hankinson J., Brusasco V., Burgos F., Casaburi R., Coates A. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith R.E., Smoll F.L., Cumming S.P., Grossbard J.R. Measurement of multidimensional sport performance anxiety in children and adults: the sport anxiety scale-2. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2006;28:479–501. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zauner C.W., Benson N.Y. Physiological alterations in young swimmers during three years of intensive training. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1981;21:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kesavachandran C., Nair H.R., Shashidhar S. Lung volumes in swimmers performing different styles of swimming. Indian J Med Sci. 2001;55:669–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganong W.F. 21st ed. McGraw Hill; Boston: 2003. Pulmonary function. Review of medical physiology; pp. 649–666. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parshad O., Richards A., Asnani M. Impact of yoga on haemodynamic function in healthy medical students. West Indian Med J. 2011;60(2):148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshi L.N., Joshi V.D., Gokhale L.V. Effect of short term pranayama on breathing rate and ventilatory functions of lungs. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;36(2):105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krick S., Eul B.G., Hanze J., Savai R., Grimminger F., Seeger W. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in hypoxia-induced apoptosis of primary alveolar epithelial type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32(5):395–403. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0314OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lakhera S., Mathew L., Rastogi S.K. Pulmonary function of Indian athletes and sportsman: comparison with American athletes. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1984;28:187–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swinmane W.E. Cardio-respiratory changes in college women to competitive basketball players. J Appl Physiol. 1968;25(6):720–724. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.6.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olufeyi A., Adegoke O., Arogundade The effect of chronic exercise on lung function and basal metabolic rate in some Nigerian athletes. Afr J Biomed Sci. 2002;5:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaya M.S., Kurpad A.V., Nagendra H.R., Nagarathna R. The effect of long term combined yoga practice on the basal metabolic rate of healthy adults. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]