Abstract

Introduction

Early prediction of severity of acute pancreatitis (AP) by a simple parameter that positively correlates with the activation stage of the immune system would be very helpful because it could influence the management and improve the outcome. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) play a critical role in the pathogenesis systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and severity of AP. One of the effects of IL-1 and TNF-α is an increase in the number of immature granulocytes (IGs) in the peripheral blood.

Aim

To assess whether the IGs% in plasma could be an independent marker of AP severity.

Material and methods

A cohort of 77 patients with AP were prospectively enrolled in the study. The IGs were measured from whole blood samples obtained from the first day of hospitalization using an automated analyser.

Results

We observed 44 (57%) patients with mild AP, 21 (27%) patients with moderate severe AP (SAP) and 12 (16%) patients with SAP. The cut-off value of IGs was 0.6%. The IGs > 0.6% had a sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value of 100%, 96%, 85.7%, and 100%, respectively (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.98). On admission, SIRS was present in 25 (32%) patients. We found that in patients who fulfilled at least two criteria for SIRS, SAP could be predicted with 75% sensitivity and 75.4% specificity, positive predictive value 36%, negative predictive value 94.2%.

Conclusions

The IGs% as a routinely obtained marker appears to be a promising, independent biomarker and a better predictor of early prognosis in SAP than SIRS and white blood cell.

Keywords: acute pancreatitis, prediction, immature granulocytes, systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP), despite being an inflammatory and usually a self-limiting disease, continues to show a widespread spectrum of severity, from mild to severe, including fatal cases. Severe AP (SAP) is found to occur in approximately 10% to 20% of patients [1, 2], with most of those cases showing pancreatic damage leading to the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [3–6]. The SIRS is considered to be one of the most important factors underlying the occurrence of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [7], while MODS is responsible for most of the morbidity and mortality cases in SAP [8, 9].

When trying to improve treatment results in SAP, we should focus on the following aspects: early administration of enteral nutrition [10], early identification of patients with poor prognosis, treatment under intensive current unit (ICU) conditions [11], and taking endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) into consideration in patients with gallstone-induced disease.

It is of the utmost importance to assess the severity of disease in the management of AP. Various factors (C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, procalcitonin, interleukins) have been evaluated in the last few decades with respect to their value for the prediction of AP results [12–15]. In our previous studies, we positively assessed the exponents of hypovolaemia and kidney injury neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as good predictors of AP [16, 17]. We also found the soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) level to be a promising new indicator of prognosis in SAP at an early stage of the disease [18].

One of the most frequently assessed parameters, CRP, is found to be non-specific for AP. Moreover, its increase is observed after 48 h [19] from the onset of symptoms, whereas these are the first 2 days of AP that are critical for implementation of appropriate fluid therapy and endoscopic procedures. Thus, there exists a need for the detection of a new parameter of inflammation, which would be applied as a rapid marker in the early prognosis of the AP course.

Early prediction of severity of AP by a simple parameter, which would positively correlate with the stage of immune system activation, would be of great value because it may direct management and improve patient outcome. Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) play a critical role in the pathogenesis and severity of AP. They have been used as biomarkers of disease severity on admission [20]. Many cytokines are expensive to measure and are often unavailable in many mid-sized clinical laboratories. The morphological and functional evaluation of leukocytes, on the other hand, can be regarded as more affordable and thus as a practical strategy for monitoring of the inflammatory response in AP. One of the effects of IL-1 and TNF-α is an increase in the number of immature leukocytes in peripheral blood [21]. Immature granulocytes (IGs) found in the peripheral blood provide important information regarding enhanced activity of the bone marrow. That is why evaluation of IGs% seems to be a promising prognostic alternative in AP.

The population of immature granulocytes encompasses metamyelocytes, myelocytes, and promyelocytes. Neutrophils and myeloblasts as well as type I promyelocytes (those that are not forming granulations) are not included.

Aim

The aim of the study was to assess whether the percentage of immature granulocytes in plasma could represent a useful indicator of AP severity.

Material and methods

A cohort of 77 patients with AP were prospectively enrolled in the study. All patients were admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology of the Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration (Poland) with a diagnosis of AP and disease onset within the last 48 h. Blood samples were obtained on admission (first 3 h) for examination of IGs% using an automated analyser. The diagnosis was established based on the presence of two of the three following features: (i) abdominal pain typical of AP, (ii) serum lipase and/or amylase three or more times the upper normal limit, and (iii) ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings suggestive of AP. Based on the presence of persistent organ failure (more than 48 h) as a criterion for the diagnosis of SAP and local complications (diagnosis of moderate severe AP (MSAP)), patients were classified into three groups: mild AP (MAP), MSAP, and SAP. The MSAP was defined as AP with transient organ failure (OF) (less than 48 h) and/or local complication, and/or systemic complication in the absence of persistent OF (more than 48 h). The SAP was defined as the persistence of organ failure exceeding 48 h. Organ failure was identified using the Modified Marshall Scoring System. The SIRS was identified during the first 24 h of hospitalisation when the patient fulfilled two or more classic diagnostic criteria. All patients were treated according to the guidelines of the Polish Pancreatic Club [22].

Counting of IGs% using an automated analyser was based on fluorescence flow cytometry combined with an adaptive gating algorithm. The IG count included promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes. It is performed in differential channels of the analyser.

Statistical analysis

The IGs% for clinical outcome prediction was assessed with receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Area under the ROC curve was computed with a 95% confidence interval to measure the usefulness of this parameter in outcome prediction. For each parameter and outcome, we set the threshold at a value that maximised the sum of sensitivity and specificity. We computed sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of different grades and groups together with their 95% confidence intervals for the threshold value.

Results

A total of 77 patients with AP (55 men and 22 women, median age: 51.4 years; range: 21–96 years) were included in the study. The AP was considered severe in 12 (16%) patients, moderately severe in 21 (27%) patients, and mild in 44 (57%) patients, according to the criteria outlined in the methodology. The aetiologies of AP included: alcoholism in 38 (49%) patients, biliary in 28 (37%) patients, and other (post-ERCP, idiopathic, hereditary, etc.) in 11 (14%) patients (Tables I, II).

Table I.

Characteristics of patients (n = 77) with acute pancreatitis included in the study

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| Age (median age; range) [years] | 51.4; 21–96 |

| Gender (male/female) | 55/22 |

| SAP | 12 (16%) |

| MSAP | 21 (27%) |

| MAP | 44 (57%) |

| Aetiology (% of total): | |

| Alcohol | 38 (49%) |

| Gallstones | 28 (37%) |

| Other causes (post-ERCP, idiopathic, hereditary etc.) | 11 (14%) |

Table II.

Factors associated with the severity of acute pancreatitis

| Parameter | Mild AP | MSAP | SAP | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 44 | 21 | 12 | |

| Age, mean ± SD [years] | 48.3 ±14.5 | 49.9 ±17.3 | 65.3 ±18.8 | 0.028 |

| Sex, n (%): | 0.216 | |||

| Women | 15 (34.1) | 6 (28.6) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Men | 29 (65.9) | 15 (71.4) | 11 (91.7) | |

| Aetiology, n (%): | 0.572 | |||

| Alcoholic | 20 (45.5) | 13 (61.9) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Biliary | 17 (38.6) | 5 (23.8) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Non-A non-B: | 7 (15.9) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (8.3) | |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 26.2 ±4.1 | 27.3 ±4.5 | 28.4 ±5.5 | 0.01 |

| WBC, mean ± SD [109/l] | 10.2 (3.4) | 13.7 (4.4) | 12.6 (6.7) | 0.012 |

BMI – body mass index, WBC – white blood cells, non-A non-B – non-alcoholic, non-biliary, SD – standard deviation.

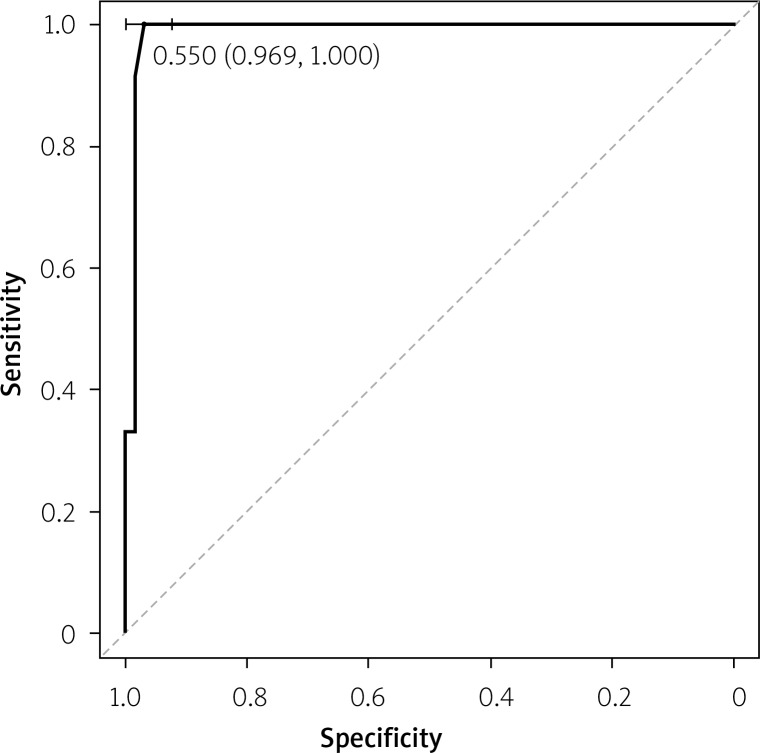

The optimal cut-off point for IGs% that distinguished SAP from MSAP and MAP was determined by constructing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. In ROC analysis, the area under the curve (AUC) for IGs was 0.989 (95% CI: 0.968–1.000) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Immature granulocytes in prediction of severe acute pancreatis (AUC = 0.989; the cutoff value is 0.6%)

The optimal cut-off point for discriminating between SAP and MSAP/MAP using IGs was 0.6%, with sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 96.9%. Positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values amounted to 85.7% and 100%, respectively (Table III).

Table III.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, diagnostic accuracy of immature granulocytes and systemic inflammatory response syndrome in predicting the severity of acute pancreastis

| Parameter | IGs (cut-off value > 0.6%) | SIRS |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100% | 75% |

| Specificity | 96.2% | 75.3% |

| Positive predictive value | 85.7% | 36% |

| Negative predictive value | 100% | 94.2% |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 97.4% | 75.3% |

On admission, SIRS was identified in 25 (32%) patients. We found that among patients who fulfilled at least two criteria for SIRS, SAP could be predicted with 75% sensitivity and 75.4% specificity, PPV 36%, NPV 94.2%.

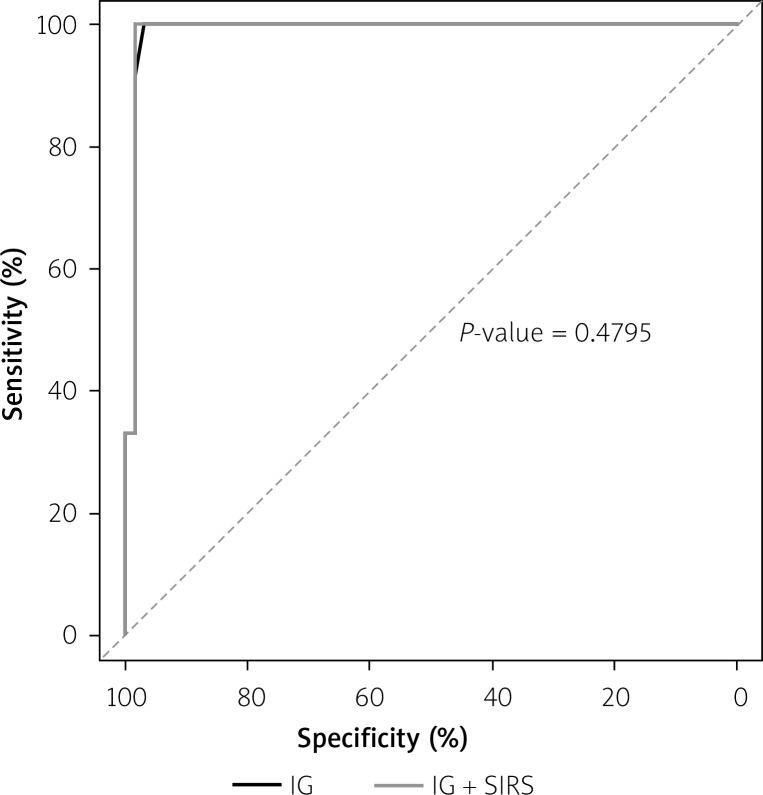

When receiver operating characteristics were used, the IGs was superior to the SIRS (p = 0.47) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves of the IGs% and systemic inflammatory response syndrome in prediction of severe acute pancreatic

Total white blood cell (WBC) count did not significantly differ between the MAP, MSAP, and SAP groups (Table II).

Two out of 2 (100%) patients with fatal AP had IGs% > 0.6. The number of patients with fatal AP was too low to conduct reliable statistical analysis.

Discussion

Early prognosis in AP, especially in the first hours, continues to be difficult and extremely challenging for clinicians. If we manage to precisely and rapidly determine the AP course in the early stage of disease, we will be able to introduce an appropriate therapeutic intervention in time. That is why the availability of simple and affordable parameters, such as the ones generated by many modern haematological analysers, should be considered a valuable perspective.

So far only a few researchers have used IGs when trying to characterise patients with SIRS and/or sepsis. The reason may be the expertise required in morphological identification of these cells by manual microscopy. This is time-consuming and labour-intensive, while three of the SIRS criteria (temperature < 36°C or > 38°C, heart rate > 90 beats/min, and respiratory rate > 20 breaths/min) are easy to obtain at the bedside. The only way to make the monitoring of IGs more widespread is to identify the cells in automated procedures.

To date, the value 0–1% was considered the reference range for IGs. However, studies conducted on analysers utilising fluorescence flow cytometry have shown that the general adult population exhibits maximal IG concentrations of 0.5% or 0.03 × 109/l [23].

Polymorphonuclear neutrophil granulocytes induced by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) develop from progenitor cells and maturate in the bone marrow over several stages into mature segmented neutrophils [24]. The maturation period lasts 7–10 days. Afterwards they migrate into the peripheral blood. Healthy individuals do not have immature granulocytes present in their peripheral blood. Therefore, the incidence of IGs in the peripheral blood is indicative of substantially increased bone marrow activation, as in different types of inflammation.

The study investigated the hypothesis that the IGs% rate is elevated in the early stage of AP and can be used as a predictor of AP severity.

According to our results, the IGs% rate was significantly increased in patients with SAP as compared to those with MSAP and MAP episodes, which makes it a potential predictor of AP severity. Considering the fact that the calculated cut-off point for prognosis in SAP is 0.6%, the sensitivity and specificity of over 90% deserves special attention.

We also showed a higher sensitivity and specificity of IGs% as compared to SIRS (sensitivity and specificity of 85% and 74%, respectively). Receiver operating curve (ROC) analyses showed that the IGs% was superior to the SIRS in the prediction of AP severity.

It is worth noting that the total WBC count was not significantly different in the study groups: MAP, MSAP, and SAP.

Further studies should also be conducted regarding elevated IGs% with fatal AP. In our study, the number of patients with fatal AP was too low to conduct reliable statistical analyses.

To sum up, our study showed that an elevated rate of IGs% in the first hours after the onset of AP symptoms indicates a severe course of AP. Introduction of fully automated haematology analysers to measure IGs would allow for rapid and early prognosis of AP.

There are only a few studies conducted to date concerning the prediction of the course of AP, which used the new criteria of disease severity. We prospectively observed patients until discharge or death to apply the revised Atlanta criteria.

However, there are certain limitations to our study. Our data came from a relatively small, single-centre cohort and, as such, require validation from external sources. That is why we believe that a prospective, multicentre study should be conducted.

Conclusions

The IGs%, a routinely obtained parameter, appears to be a promising, independent biomarker and a better early predictor of prognosis in SAP than SIRS. Further studies are required to validate the utility of IGs% in the prediction of severity and mortality in AP.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–11. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipinski M, Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Rydzewski A, et al. Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9367–72. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha A, Cader R, Akshintala VS, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome between 24 and 48 h after ERCP predicts prolonged length of stay in patients with post-ERCP pancreatitis: a retrospective study. Pancreatology. 2015;15:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar A, Chari ST, Vege SS. Can the time course of systemic inflammatory response syndrome score predict future organ failure in acute pancreatitis? Pancreas. 2014;43:1101–5. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de-Madaria E, Banks PA, Moya-Hoyo N, et al. Early factors associated with fluid sequestration and outcomes of patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong WT, OndrejkovÁ A, Vege SS. Predictors and outcomes of moderately severe acute pancreatitis – evidence to reclassify. Pancreatology. 2016;16:940–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson CD, Besselink MG, Carter R. Acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2014;349:g4859. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Ke L, Tong Z, et al. Association between severity and the determinant-based classification, Atlanta 2012 and Atlanta 1992, in acute pancreatitis. A clinical retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e638. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao JG, Liao Q, Zhao YP, et al. Mortality indicators and risk factors for intra-abdominal hypertension in severe acute pancreatitis. Int Surg. 2014;99:252–7. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00182.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu XM, Liao YW, Wang HY, et al. When to initialize enteral nutrition in patients with severe acute pancreatitis? A retrospective review in a single institution experience (2003–2013) Pancreas. 2015;44:507–11. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasparović V, Daković K, Gornik I, et al. Severe acute pancreatitis as a part of multiple dysfunction syndrome. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner J, Hartwig W, Uhl W, et al. Useful markers for predicting severity and monitoring progression of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2003;3:115–27. doi: 10.1159/000070079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezmarevic M, Mirkovic D, Soldatovic I, et al. Correlation between procalcitonin and intra-abdominal pressure and their role in prediction of the severity of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2012;12:337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisic E, Poropat G, Bilic-Zulle L, et al. The role of IL-6, 8, and 10, sTNFr, CRP, and pancreatic elastase in the prediction of systemic complications in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:282645. doi: 10.1155/2013/282645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta S, Shekhawat VP, Kaushik GG. D-dimer, a potential marker for the prediction of severity of acute pancreatitis. Clin Lab. 2015;61:1187–95. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2015.150102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipinski M, Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Rydzewski A, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as an early predictor of disease severity and mortality in acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2015;44:448–52. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipinski M, Rydzewski A, Rydzewska G. Early changes in serum creatinine level and estimated glomerular filtration rate predict pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute pancreatitis: creatinine and eGFR in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:207–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipinski M, Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Rydzewski A, et al. Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) in patients with acute pancreatitis (AP) – progress in prediction of AP severity. Pancreatology. 2017;17:24–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staubli SM, Oertli D, Nebiker CA. Laboratory markers predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52:273–83. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2015.1051659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papachristou GI. Prediction of severe acute pancreatitis: current knowledge and novel insights. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6273–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinay K, Nelso F, Abul A. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004. pp. 84–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosołowski M, Lipiński M, Dobosz M, et al. Management of acute pancreatitis (AP) – Polish Pancreatic Club recommendations. Gastroenterology Rev. 2016;11:65–72. doi: 10.5114/pg.2016.60251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiland T, Kalkman H, Heihn H. Evaluation of the automated immature granulocyte count (IG) on SysmexXE-2100 automated haematology analyser vs. visual microscopy (NCCLS H20-A) Sysmex J Int. 2002;12:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nierhaus A, Klatte S, Linssen J, et al. Revisiting the white blood cell count: immature granulocytes count as a diagnostic marker to discriminate between SIRS and sepsis – a prospective, observational study. BMC Immunol. 2013;14:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-14-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]