Abstract

Constitutive behaviors of an interstitial-free steel sample were measured using an augmented Marciniak experiment. In these tests, multiaxial strain field data of the flat specimens were measured by the digital image correlation technique. In addition, the flow stress was measured using an X-ray diffractometer. The flat specimens in three different geometries were tested in order to achieve 1) balanced biaxial strain, and plane strain tests with zero strain in either 2) rolling direction or 3) transverse direction. The multiaxial stress and strain data were processed to obtain plastic work contours with reference to a uniaxial tension test along the rolling direction. The experimental results show that the mechanical behavior of the subjected specimen deviates significantly from isotropic behavior predicted by the von Mises yield criterion. The initial yield loci measured by a Marciniak tester is in good agreement with what is predicted by Hill's yield criterion. However, as deformation increases beyond the vonMises strain of 0.05, the shape of the work contour significantly deviates from that of Hill's yield locus. A prediction made by a viscoplastic self-consistent model is in better agreement with the experimental observation than the Hill yield locus with the isotropic work-hardening rule. However, none of the studied models matched the initial or evolving anisotropic behaviors of the interstitial-free steel measured by the augmented Marciniak experiment.

Keywords: Crystal plasticity, X-ray diffraction, Multiaxial stress, Yield surface, Digital image correlation

1. Introduction

Accurate description of the flow stress behavior in multiaxial deformation is important for sheet metal forming simulations since the engineering metal sheets in general undergo multiaxial stress/strain paths during the stamping process. In the literature various experimental methods are discussed in order to obtain multiaxial constitutive behaviors. For example, a hydraulic biaxial bulge test has been used to characterize the work-hardening behavior of thin sheets for an extended amount of deformation [1–3]. Alternatively, tests using cylindrical tubes allow various ratios of the stress components to be tested by controlling the internal pressure in combination with axial loading [4–7]. However, both of these test methods involve bending of the specimen with varying curvature, leading to ambiguities in the stress state through the thickness direction. The use of a flat cruciform specimen may reduce the through-thickness stress gradient by applying the deformation or force in the plane of the specimen [8]. However, tests using cruciform specimens typically experience failure prior to the material failure limits due to unwanted strain/stress concentration near the corners of the samples.

This article focuses on an experimental technique using a combination of in-situ X-ray diffraction and digital image correlation (DIC) applied to a recessed Marciniak punch. Similar studies are found in Refs. [9] and [10] where high energy X-ray and neutron were used, respectively, with deformation applied to cruciform shaped specimens in an area of reduced thickness. The technique under current investigation is slightly different from the mentioned experimental methods since a low power X-ray source is utilized in conjunction to a forming limit test without thinning the sheet sample. The current technique was successfully applied previously for aluminum alloys [11,12]. In a related, but limited, study by the current authors, this experimental technique was also applied for an interstitial-free (IF) steel under equi-biaxial deformation [13]. The {211} diffraction plane was chosen for the steel samples due to its large multiplicity, high 2θ angle, high intensity, and low fluorescence when investigated with a chromium X-ray source. A concomitant disadvantage of using the {211} plane is that the simple sin2 ψ method cannot be applied for the stress analysis [14,15]. For this reason, a method using more general diffraction elastic constants was required [13,16]. In the current experiment the gauge area of stress measurement is confined to the size of the X-ray beam in use, that is approximately 2 mm diameter. The small gauge area and flat recessed punch remove bending effects found in the tube and bulge tests. The balanced biaxial stretching by a recessed Marciniak sample is compared with the data obtained by a bulge experiment from a previous study [13]. In the current article, the experimental results obtained by the recessed Marciniak test will be compared to two modeling frameworks: 1) macro-mechanical approach using von Mises and Hill's yield criteria with isotropic hardening; 2) micro-mechanical approach using the viscoplastic self-consistent crystal plasticity code developed by Lebensohn and Tomé [17].

2. Experimental setup

2.1. Marciniak recessed punch test

A Marciniak recessed punch was used in this study. A rectangular flat specimen is stacked with a washer that has a 32 mm diameter circular hole so that the central area of the specimen remains frictionless [11–13,18,19]. The speed of the punch movement was maintained to be 0.1 mm/s such that the von Mises strain rate on the top surface of the sample remained on the order of 10−3 s−1 within the investigated amount of deformation for all the strain paths investigated (see below). The punch stroke is interrupted after strain increments of approximately 0.02 so that in-situ X-ray diffraction can be used. During diffraction, the position of the punch remains constant (displacement control).

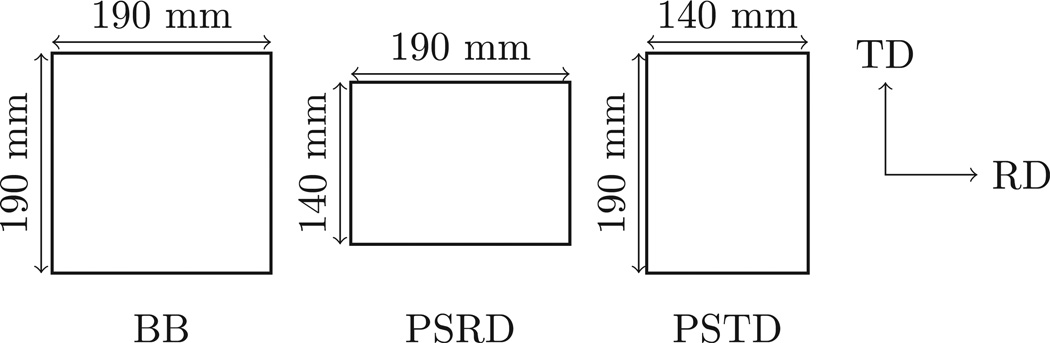

For the Marciniak test, the initial sample dimensions control the strain path of tested specimen. Three different dimensions of the sample were used for three different loading paths – see Fig. 1. The abbreviated terms, namely, BB, PSRD, and PSTD, refer to balanced biaxial, plane strain RD (zero strain along TD) and plane strain TD (zero strain along RD), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Sample dimensions for balanced biaxial (BB), plane strain RD (PSRD), and plane strain TD (PSTD).

The orthotropic axes of the rolled IF steel specimen remain coincident with the stretching axes. Under such a circumstance the orthotropic sample symmetry is preserved. Therefore, the resulting stress response of the specimen can be mapped to the Cartesian space of two normal stress components, i.e., Σ̅11 and Σ̅22, with the two basis vectors (ē1 and ē2) being parallel to RD or TD for the entire deformation. A similar representation is also valid for the strain data, as they can be mapped to the Cartesian space of two normal strain components, i.e., Ē11 and Ē22.

2.2. Digital image correlation technique

Stereo digital image correlation (DIC) was used to measure the 3D surface shape and displacements during the Marciniak test, and the strains were calculated from this displacement field. During the test, the surface of the specimen moves with respect to the cameras, due to the punch motion. Therefore a DIC system capable of compensating for any out of plane motion or shape change was required. The top surface of the specimen was painted using matte black speckles on a matte white background along with lines to orient the sample RD and TD directions. The surface was not patterned above the very center of the Marciniak punch where X-ray measurements were performed. This was done to prevent the paint from biasing the X-ray auto-focus distance, and to remove unwanted attenuation of the X-ray signal. The system used a pair CCD cameras with matching compact 35 mm lenses. An f-stop of approximately 12 resulted in a sufficient depth of field to keep the specimen properly in focus throughout the test. The cameras were upgraded during the series of tests resulting in some tests using a pair of 2 megapixel cameras with an average magnification of 14.8 pixels/mm while the other tests used a pair of 5 megapixel cameras with a 23.5 pixel/mm magnification. In both cases, the cameras were spaced at approximately 220 mm with a stereo angle between them of approximately 28°. The system was oriented at an approximately 38° angle to the surface normal with an initial standoff distance of 480 mm, so that it would not restrict access for X-ray diffraction measurements. The correlations were calculated using commercial DIC software (VIC3D). Two sets of correlation parameters were used such that the physical width used in each strain measurement was approximately 2.6 mm. This required square correlation subsets 29 pixels wide stepped in 7 pixel increments for the 5 megapixel cameras, and subsets 13 pixels wide stepped in 5 pixel increments for the 2 megapixel cameras. After measurement, the 3D coordinates and displacements were rotated to the RD direction and the initially flat surface. True strains in the RD, TD, and shear between them were calculated from the measured displacement field and filtered using a Gaussian weighted filter with a diameter of five step locations. The noise floor was assessed for each specimen using zero strain rigid body motions resulting in one standard deviation of axial strains less than 0.003, and one standard deviation of von Mises equivalent strain less than 0.007.

2.3. In-situ X-ray experimental conditions

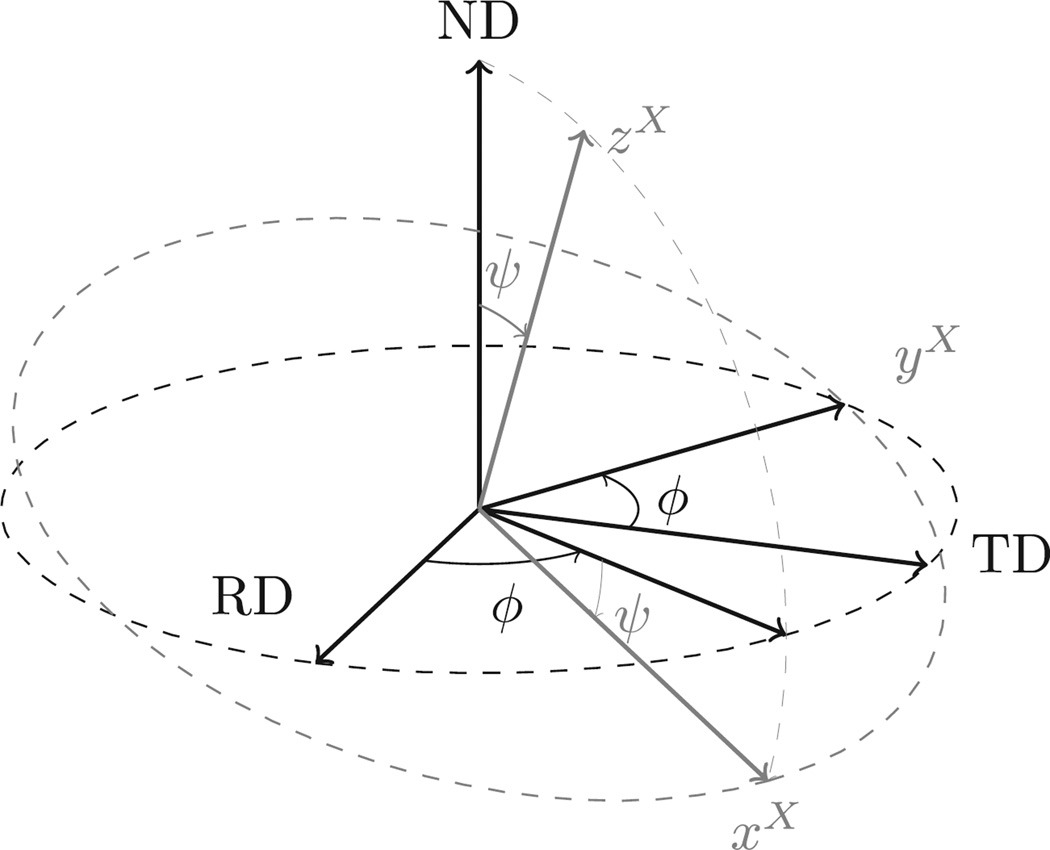

For the X-ray diffraction measurements, a Cr tube energized with 20 kV and 4 mA was used. The {211} diffraction peak was collected using Cr Kα radiation. The peak measurements were made using two detectors located in the plane of xX − zX, which are symmetrically around the incident X-ray beam (zX) – refer to Fig. 2 for the directions of the mentioned axes in reference to material axes (RD/TD/ND). Then, the in-situ d-spacing was obtained by fitting the diffraction peak with Gaussian distribution function. The d-spacings were collected at various diffraction orientations (ϕ, ψ) as illustrated in Fig. 2. The maximum tilting ψ rotation was confined to ±34.8° due to geometric constraints and the use of the reflection method. Diffraction peaks were collected at 13 ψ angles (7 tilt angles sampled by the two detectors with an overlap at ψ = 0°). At each tilt angle, the sample was exposed to the X-ray beam for 20 s. The set of 7 tilts was repeated at 4 different rotation (ϕ) angles, i.e., 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°. The diffraction elastic constants (DECs) required to obtain the stress from the measured d-spacing were measured through independent ex-situ X-ray experiments with miniature tensile bars cut from samples after various deformation levels. The detailed method for the experimental measurements on the DECs is discussed elsewhere [13,20].

Fig. 2.

The diffraction orientation (ϕ, ψ) with respect to the orthotropic sample axes (RD, TD, ND) is illustrated; ϕ is the in-plane rotation whereas ψ is the ‘tilting’ angle from the specimen normal direction. Note that zX axis is parallel to the diffracting plane normal, and it bisects the X-ray beam path.

Each specimen tested in the Marciniak system was held under a constant punch-displacement during the in-situ X-ray diffraction measurements. It is recognized that such displacement holds may result in sample relaxation due to strain-rate sensitivity and visco elastic/plastic properties of the material. It is noted that the X-ray measurements were performed after a sudden drop in punch force signal (typically less than 4% of the force in approximately 5 s) that occurs at the start of the hold of displacement. The individual measurement at each deformation increment (including all four ϕ rotations and all seven ψ tilt angles) took approximately 15 min. Given the temperature, holding-time and material (IF steel), effect of the creep during holds should be negligible [21]. Therefore, in the remainder of the current article, the resulting stress analyzed by the current X-ray system is regarded as a static response of this material.

3. Data analysis

3.1. Strain analysis

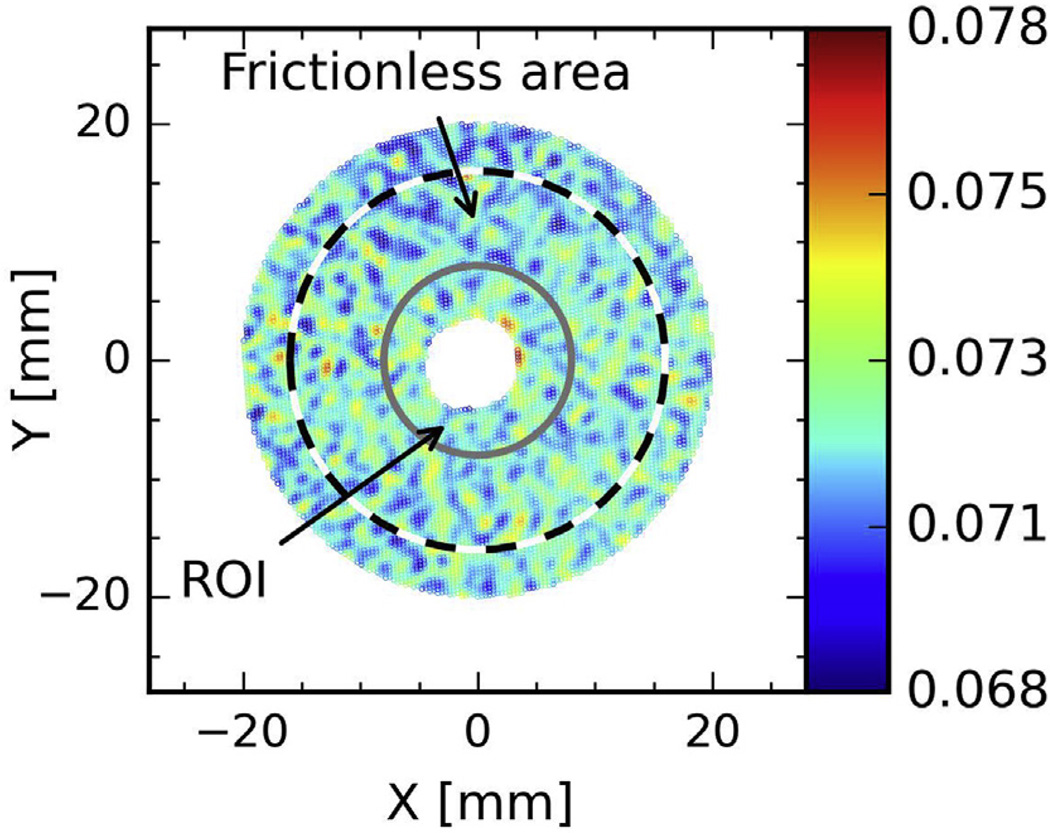

The speckle pattern sprayed on specimen enables the post-analysis software (VIC3D) to recognize the spatial coordinates of the subjected specimen. Since d-spacings should be collected from the top surface as well, the central region is not patterned to allow the X-ray beam clear access – see the absence of strain data around (0,0) coordinate in Fig. 3. Consequently, the plastic strain of the exact spatial coordinate in diffraction condition cannot be obtained. In this study, the representative strain is approximated by the average strain data within a region of interest (ROI) that has a radius of 8 mm – see Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

A DIC map of the strain data in units of von Mises true strain; Notice that 1) the region of interest (ROI – gray circle) within which the representative strain is estimated has a radius of 8 mm; 2) the ROI is much smaller than the size of frictionless area (the dashed line); and 3) the speckle pattern is absent in the center to allow the X-ray beam clear access to the bare specimen surface, thus there is no strain data therein.

3.2. Multiaxial flow stress measurements using X-ray

In the stress analysis based on the in-situ X-ray diffraction method, the diffraction strain (εd) has a linear relationship with the ‘unknown’ macroscopic stress (Σ̅ij):

| (1) |

in which F denotes the diffraction elastic constants (DEC) (or stress factor following the terminology of [22–24]). Note that DECs and diffraction strain are associated with a specific diffraction plane {hkl} for a certain diffraction orientation (ϕ, ψ). As mentioned earlier in Section 2.3, the DECs used in this study were measured by ex-situ X-ray diffraction for specimens after various plastic deformations. According to Eq. (1), the macroscopic stress can be obtained from the diffraction strain provided that the DECs are known. In the current study, lattice strains were collected only from {211} lattice plane. Moreover, only two stress components (i.e., Σ̅11 and Σ̅22) were invoked due the fact that the axes of orthotropic anisotropy of the subjected material remain coincident with the stretching axes. To that end, Eq. (1) reduces to:

| (2) |

The following objective function (denoted as G) was minimized in order to obtain the two stress components:

| (3) |

where denotes the measured diffraction strain. The two stress components (i.e., Σ̅11 and Σ̅22) obtained at the minimum value of G are considered as the experimental stress obtained by the current X-ray method. Additional details of stress factors and diffraction elastic constants are available in Refs. [14,15,22,25]. The computational realization of the stress analysis used in this work is available in DiffStress package [26].

There are various factors that influence the measurement precision of the stress obtained by the X-ray diffraction method. For example, the number of tilt angles need to be sufficient to cover the ψ range of interest, but more sampling angles that overlap add time to the measurement with little improvement in precision. The level of counting statistics error is also an important factor that influences the precision. Also, the number of plastic levels at which DECs are measured has a significant influence in the measurement uncertainty. A systematic investigation on the precision of the measurement was performed by the authors and is available elsewhere [27].

4. Constitutive models

4.1. Macro-mechanical models

Based on the associated flow rule, the yield function is used as the plastic flow potential as well. Isotropic hardening is customarily assumed in the community of sheet metal forming, due to its simplicity. Isotropic hardening assumes that the yield surface expands equally in any stress direction in proportion to plastic work per unit volume. As a result, the yield surface remains concentric in deviatoric stress space regardless of the plastic deformation that the subjected material experiences.

In this work, two continuum scale phenomenological yield loci are studied: 1) von Mises isotropic yield locus; 2) Hill's anisotropic yield locus characterized by two R-values [28].

Von Mises stress is defined as:

| (4) |

with S̅ij being the deviatoric stress (i.e., with δij = 1 when i = j otherwise zero). A quadratic anisotropic yield criterion for plane stress condition (as a function of two stress components) following Hill48 yield function [28] is also considered. The below criterion is used in this study, and is characterized by two R-values (RRD and RTD).

| (5) |

Note that the two R-values in use were characterized by uniaxial tension tests along the RD and TD: RRD = 2.1 and RTD = 2.7.

4.2. Viscoplastic self-consistent crystal plasticity model

The VPSC7b code developed by Ref. [17] is used for this study. The viscoplastic shear strain γ̇s for the slip system s is related to the resolved shear stress τs in the form of n-th power law [29].

| (6) |

in which γ0 is the normalization factor; is the critical resolved shear stress (CRSS) for the slip system s. The local viscoplastic strain pertains to a grain based on the above power law, which leads to below [17,30]:

| (7) |

where ms and σ denote the Schmid tensor and the local stress, respectively.

The strain hardening is described as a function of accumulated shear strain (Γ) as described in Ref. [31] using:

| (8) |

in which four strain-hardening parameters, and are introduced. See Table 1 for parameters identified using the data obtained through uniaxial tension along RD based on the Simplex algorithm [32] available in SciPy package [33]. Two slip system families were used: {110}〈111〉 and {112}〈111〉. Crystallographic texture of the as-received IF steel sample was measured through neutron diffraction in the National Institute of Standards and Technology Center for Neutron Research and analyzed by MTEX [13,34]. Spherical grains were used.

Table 1.

Strain-hardening parameters for VPSC model; parameters in [MPa] unit.

| τ0 | τ1 | θ0 | θ1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 87.3 | 123 | 761 | 8.46 |

The descriptions presented from Eqs. (6)–(8) pertain to the local constitutive behavior on each slip system of individual grains. Those equations should be solved iteratively through the self-consistent scheme [17,30,35]. The VPSC program was used to run for a fixed set of either constant strain (constant Ēxx/Ēyy) or stress paths (constant Σ̅xx/Σ̅yy). Both cases were examined, and no significant dissimilarity was found for the IF steel texture. The results shown use a constant stress ratio.

5. Results

The Marciniak punch test described in Section 2.1 has traditionally been used as a forming limit test that subjects the material to a nearly constant in-plane strain ratio until strain localization and eventual fracture. This ability to deform a sheet material to such high strains (e.g. beyond the ability of a cruciform test) is a key reason it was chosen to perform the biaxial deformations. However, the combined Marciniak, X-ray diffraction, and DIC technique, as described here, is only intended for homogenous macro-scale stress and strain fields. Use of this technique for spatially varying stress and strain fields is beyond the scope of this work. This limits the use of the results to a range of strains before localization. At any strain after localization, the measurements will be further complicated by potentially varying strain rates and force shedding outside versus inside the localization. Therefore only the portion of the strain range where no strain localization is measured (beyond the DIC noise floor) should be used.

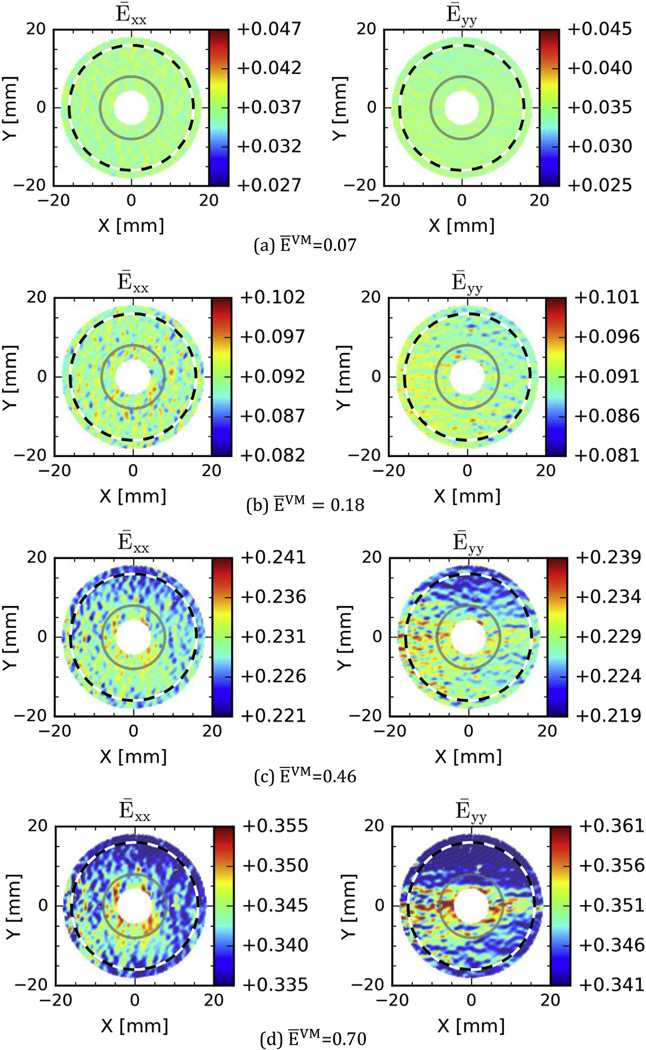

In Fig. 4, a series of strain maps are shown for one balanced biaxial test. The Ēxx and Ēyy strain components are plotted at four average von Mises effective strain (ĒVM) levels in the region of interest (ROI). In each subfigure, the color map range is centered on the average strain in the ROI ± 0.01 strain (that ± range is approximately 3.3 times the noise floor described in Section 2.2). Fig. 4a and b shows some minor spatial variation in strain for both Ēxx and Ēyy, but it is predominantly distributed within the noise floor variation about the average value or is dispersed about the strain map. However, Ēyy in Fig. 4c and d shows a spatial variation that is more systematic and appears as a band of higher Ēyy aligned to the X direction, especially about Y = 0 mm for Fig. 4d. It should be noted that the failure of the current IF steel subjected to initially BB tension is expected to be in a band aligned with the RD with TD strains higher than the area outside of the band. The higher strain region in Ēyy of Fig. 4d is in agreement with this behavior.

Fig. 4.

Color maps of axial strains at four average von Mises strain (ĒVM) levels – the maximum and minimum limits of the color bar was set to be the average value ±0.01 strain within the ROI; The (X,Y) coordinates are referring to initial material points prior to stretching. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The results shown in Fig. 4 and the applicability limit of the combined Marciniak, X-ray diffraction, and DIC technique to macroscopically homogenous deformation, suggest that the limit of application of the technique for this material would be after ĒVM = 0.18 strain but before ĒVM = 0.46 strain (Fig. 4b and c) for the BB strain path. Based on these and similar data for the other strain paths, the limits of analysis of the data were set as shown in Table 2, as conservative limits of application, while we leave more complex analysis of the data beyond these strains for future work.

Table 2.

Maximum strains used for stress-strain data, these are conservatively prior to strain-localization.

| BB | PSRD | PSTD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum ĒVM | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

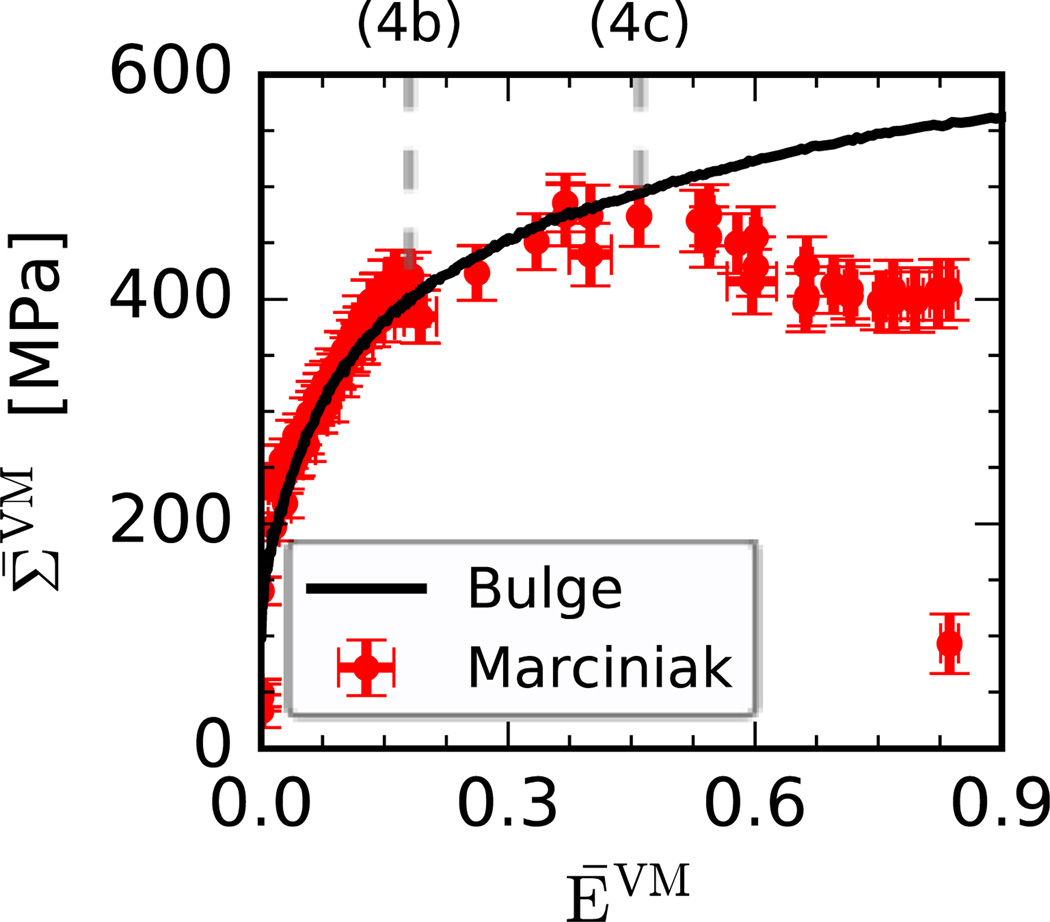

The data resulting from the balanced biaxial deformation mode is shown in Fig. 5, in which five separate data sets are combined into a single plot of von Mises stress (Σ̅VM) and ĒVM. The experimental flow stress-strain data points obtained by the current Marciniak X-ray test are compared with the data measured using the bulge test data from Ref. [13]. The stress uncertainties are based on counting statistics considering the diffraction peak intensity counts, and the strain uncertainties are based on one standard deviation within the ROI. Fig. 5 marks the level of strains from Fig. 4 as dashed gray lines for cross-reference. One can notice that the flow stress measured by X-ray is in good agreement with the bulge test up to ĒVM = 0.40 strain. However, as the deformation increases further, the stress gradually decreases, thus deviating significantly from that of the bulge test result.

Fig. 5.

Flow stress and strain for the case of balanced biaxial (BB) strain path in comparison with the result based on a bulge test: gray dashed lines refer to Fig. 4b and c; More detailed comparison confined to a von Mises strain of 0.2 is available in Fig. 7. The bulge test data and one balanced biaxial test were originally presented in Refs. [13], here the results of additional tests are plotted versus von Mises strain averaged over the ROI.

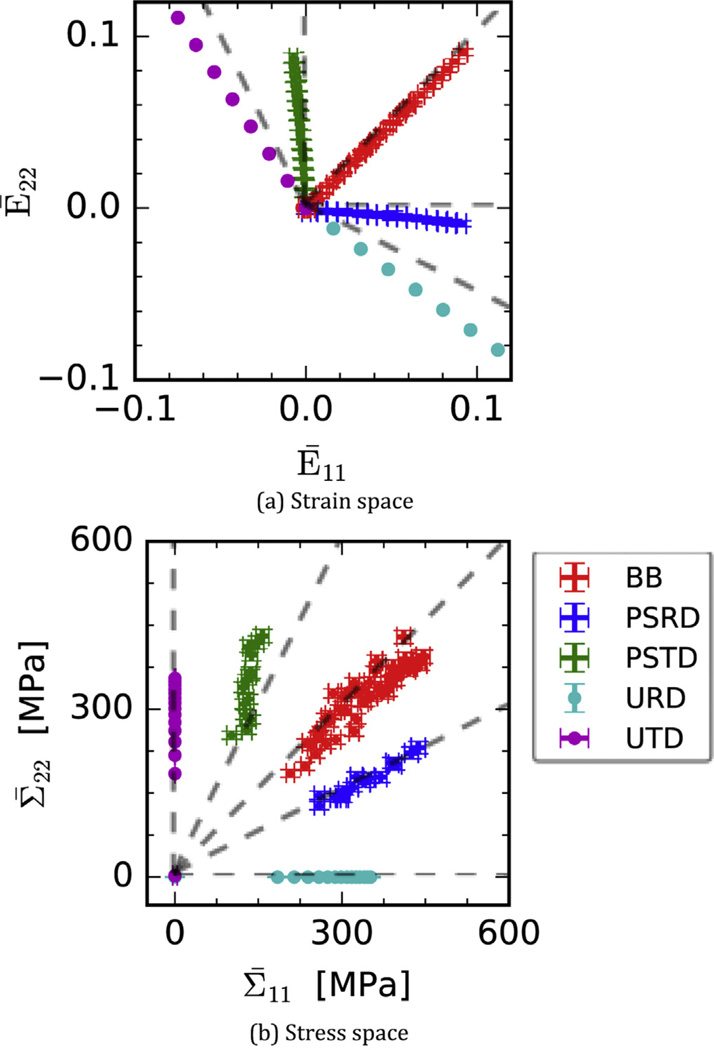

In Fig. 6 the resulting multiaxial strain and stress data for BB, PSRD, and PSTD are displayed in the 2D strain (Ē11, Ē22) and stress (Σ̅11, Σ̅22) Cartesian coordinates together with the data obtained by uniaxial tension tests along RD and TD (denoted as URD and UTD, respectively). In Fig. 6a the strain paths of the uniaxial tension tests deviate from the gray guide lines pertaining to the isotropic case (i.e., R-value of 1 in both RD and TD) due to planar anisotropy of the IF steel. Meanwhile, the strain path of BB aligns well with the dashed diagonal line, whereas the actual strain path for PSRD and PSTD experiments slightly deviate from the ideal plane strain conditions shifting towards the respective uniaxial strain paths. In the stress map (Fig. 6b), the ratio of the two stress components obtained by the X-ray diffraction method is shown for the multiaxial stress paths. In case of BB, the stress corresponding to the equi-biaxial strain slightly deviates from the ideal equi-biaxial stress path shifting to Σ̅11 > Σ̅22. For the PSRD mode, despite of the deviation from the plane-strain path show in Fig. 6, the ratio of Σ̅11 to Σ̅22 roughly remained 0.5. In case of PSTD the initial value of the stress component ratio (i.e., Σ̅22/Σ̅11) is roughly located at the gray line but eventually shifting towards Σ̅22/Σ̅11 <0.5. Note that stress data points corresponding to the elastic regime were removed for better visualization.

Fig. 6.

Stress/strain paths measured during this study. The two uniaxial stress behaviors (URD and UTD) were separately measured using a uniaxial specimen and a universal testing machine. Uncertainties in strain for multiaxial data pertain to the standard deviation of DIC data collected in ROI; Uncertainties in stress for multiaxial data were estimated by counting statistics in diffraction peaks. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The collection of discrete stress and strain data shown in Fig. 6 was interpolated using a continuous and analytic function. To that end, the Voce hardening description in Eq. (7) was used:

| (9) |

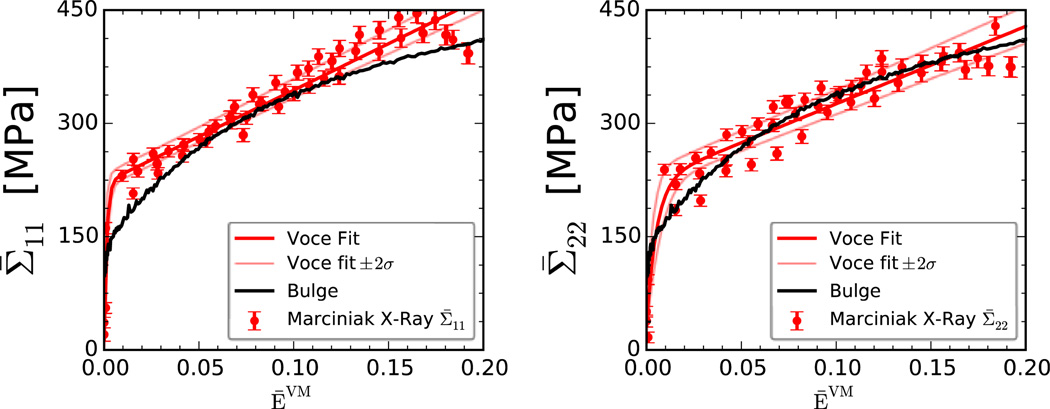

In the above individual stress components (Σ̅11 and Σ̅22) are treated as functions of the von Mises strain (ĒVM). The Voce hardening parameters for each of the deformation modes were fitted using the Optimize package in SciPy [33]. Fig. 7 compares the collection of stress and strain data from BB and its corresponding fittings for the two stress components. The bulge test result is shown in both plots assuming that the bulge test induces the balanced biaxial stress condition, i.e., Σ̅11 = Σ̅22 = Σ̅VM. The same procedure is repeated for both PSRD and PSTD. Parameters determined by this procedure are listed in Table 3.

Fig. 7.

The collection of stress-strain data for the BB deformation mode and the corresponding fitted results using the Voce model for Σ̅11 and Σ̅22 components against the von Mises strain through Eq. (7).

Table 3.

Voce hardening (Eq. (12)) parameters tuned for each stress component of individual paths.

| a [MPa] | b0 [MPa] | c | b1 [MPa] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB | Σ̅11 | 221.0 | 205.1 | 1230 | 709.3 |

| Σ̅22 | 223.1 | 187.7 | 1028 | 186.7 | |

| PSRD | Σ̅11 | 231.1 | 201.0 | 1058 | 996.0 |

| Σ̅22 | 112.2 | 671.9 | 593.3 | 3125 | |

| PSTD | Σ̅22 | 117.2 | −35.2 | 144.8 | 2461 |

| Σ̅22 | 144.7 | −109.2 | 1827 | 19.47 |

The strain data obtained by DIC technique is a summation of the macro-scale elastic and plastic strains. The plastic strain is estimated on the basis of additive decomposition of the total strain as below:

| (10) |

The elastic strain is determined by assuming isotropic elasticity under plane stress condition (Σ̅33 = 0) using:

| (11) |

An elastic modulus of 200 GPa and Poisson ratio 0.3 were used. In the case of a uniaxial flow stress of 300 MPa (i.e., approximately the von Mises flow stress at the von Mises strain of around 0.07), the approximated macro-scale elastic strain would be 0.0015 (i.e., 300 MPa/200 GPa = 0.0015). This value is within the error in the DIC axial strain data reported in Section 2.2. Yet, the retention of the elastic portion of strain would lead to a systematic bias in the experimental data. Details of the elastic strain beyond isotropic elasticity would be impossible to resolve currently and are neglected. The accumulative plastic work up to a selected level of deformation can be obtained as below:

| (12) |

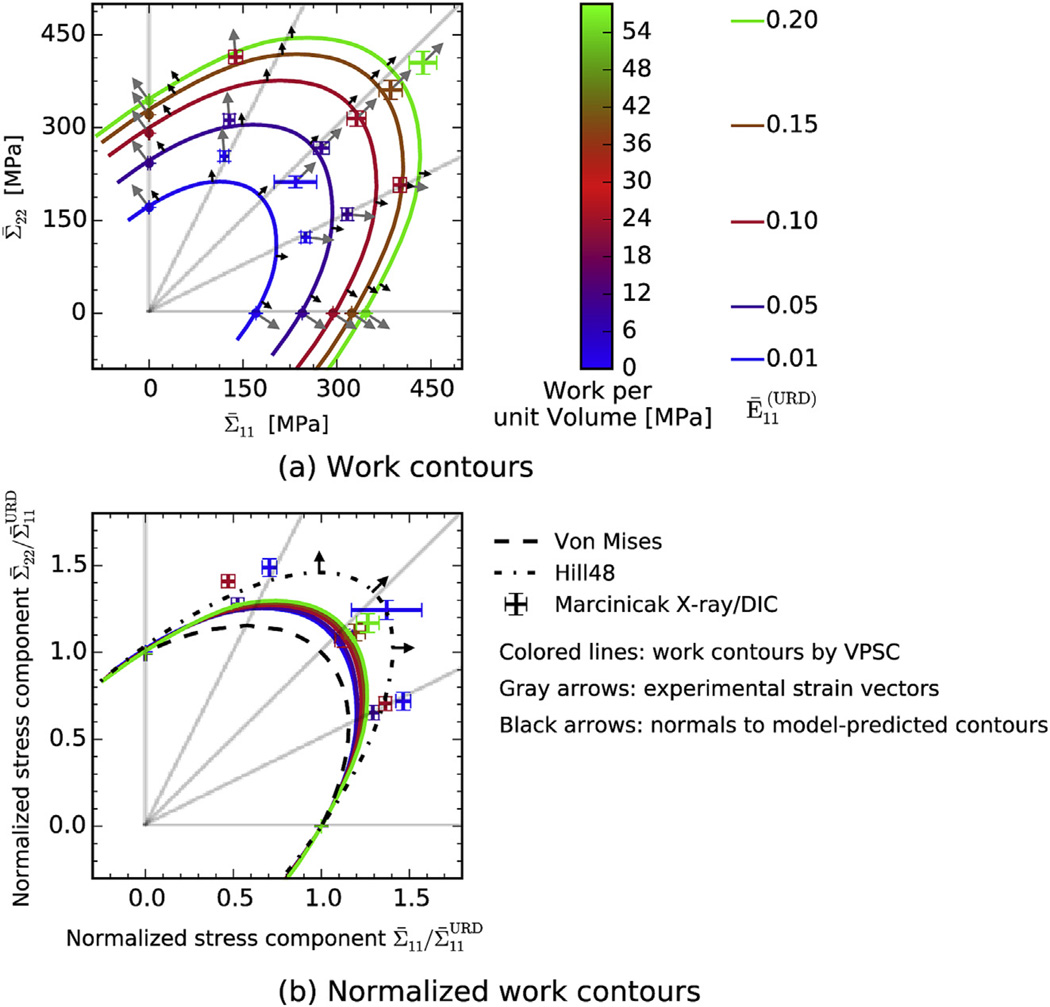

The fitted functions of the form shown in Eq. (9) were used to determine the multiaxial work hardening behavior as shown in Fig. 8, where the stress error bar pertains to the uncertainty associated with fitting as shown in Fig. 7. In this figure a selected set of work levels was used in reference to various uniaxial strains of URD (denoted as ĒURD). Note that the initial stress responses interpolated for the work level lower than ĒURD = 0.01 have an error estimate that is exceedingly large; likely due to the presence of residual stress. Therefore, only the data obtained for ĒURD ≥ 0.01 are considered here. A set of 5 different work levels is considered that correspond to 5 different values of ĒURD (0.01, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, and 0.20). Plastic works corresponding to the selected levels of ĒURD are represented by the color map. The plastic work contours normalized by the Σ̅11 component of URD are shown in Fig. 8b. VPSC model predictions (that are coded using the same color-map) as well as yield loci calculated by von Mises and Hill48 yield criteria (the dashed line and black bold line, respectively) are included in the figure for comparison. As opposed to the isotropic hardening behaviors based on yield loci by von Mises and Hill48, the VPSC model predictions lead to gradual shape change as depicted in colored lines in Fig. 8b.

Fig. 8.

Experimental work contours are compared with the VPSC model predictions (a); Work contours normalized by that of uniaxial tension along RD are shown in (b) together with model predictions by VPSC, von Mises yield criterion, and Hill48 model. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In addition, the two strain components are used to indicate the direction of flow in terms of a strain vector . Each of the experimental stress data (Σ̅11, Σ̅22) shown in Fig. 8a is annotated by a gray arrow that indicates the associated measured strain vector. To compare with the model predictions, the locations of model predicted work-contours that give the same direction of strain vectors are also indicated by black arrows (i.e., normal to each predicted contour in the same direction as the associated gray arrow for the measured data)– see Fig. 8a and b for the normal of the VPSC work contours and Hill 48.

The analyses on the raw data obtained by X-ray and DIC were performed using various computer programs. DiffStress was used to obtain the stress using the DECs and in-situ d-spacings from X-ray diffraction [26]. The stress uncertainty was estimated according to the counting statistics analysis. Also, DIC raw data were obtained by VIC3D and then was further analyzed using [36]. The VPSC model run was calculated using VPSC-FLD package, which is maintained in Ref. [37].

6. Discussion

Although the applicable range of the stress measurement was limited by the strain localization occurring at large plastic deformation (as discussed in Figs. 4 and 5), the augmented Marciniak testing method successfully measured various multiaxial stress/strain paths for the IF steel sample up to strain levels equal to or greater than 0.1 von Mises strain (See Table 2). A preliminary analysis of a balanced biaxial Marciniak X-ray tests was shown in Refs. [13], but the DIC strains were based on average strains across the surface smoothing any spatial variation. In Fig. 5, the same results are plotted along with the results of 4 additional tests using the average DIC strains within the ROI (see Section 3.1). This work also includes the experimental results for the plane strain paths in RD and TD. In the previous study [13], the stress drop evident after the von Mises strain level of 0.4 was not clearly understood. In the current work, new analyses using DIC data considering the inhomogeneous development of strain (Fig. 4) suggests a potential correlation with the development of strain localization. The stress drop is consistently found in the five independent tests conducted for the balanced biaxial.

The specimen geometries shown in Fig. 1 led to three distinctive multiaxial stress-strain paths as shown in Fig. 6. The combination of the X-ray diffraction method and DIC technique successfully provided valid multiaxial constitutive experimental data. The Voce hardening function (Eq. (9)) was used to obtain a smooth analytical description to facilitate further analysis as shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 shows that the flow stress measured by the bulge test is significantly lower than that measured by X-ray up to a von Mises strain of 0.05. The approximation by the smoothed curve (Eq. (9)) gave a yield stress around Σ̅11 = 220 MPa, whereas a value of 150 MPa was observed in the case of bulge test. It is well known that the bulge test may not provide reliable data in the initial deformation as the approximation to a spherical shape can be ambiguous [38]. Assuming that the flow stress measured by the current X-ray method is valid, the bulge test method may significantly underestimate the balanced biaxial yield stress.

In Fig. 8 the experimental stress states are compared with the work contours predicted by the VPSC model. At the strain of 0.01, the model prediction by VPSC is not in good agreement with the experimental stress data, except for the two uniaxial data – in fact the uniaxial along RD was used as a reference to tune the hardening parameters used in VPSC as discussed earlier in Section 4.2. The VPSC model underestimated the multiaxial flow stress level in BB, PSRD, and PSTD by 50 MPa. However, in the deformation to a level of ĒURD = 0.05, the VPSC model predictions are in good agreement with the corresponding experimental stress at BB, UTD and PSRD. At ĒURD = 0.10, the discrepancy between model-predictions and experimental data for PSRD and PSTD increases, whereas predictions for BB and UTD remain good. With further deformation ĒURD ≥ 0.15, the discrepancy with the VPSC-model for BB increases leading to an underestimation by the model in comparison with the experiment.

Comparison with the Hill and von Mises yield loci is separately estimated by the normalized work contours shown in Fig. 8b. In it, the work contours predicted by the VPSC model are also given. It should be noted that the yield locus is equivalent to the work contour when the material work-hardens isotropically. Assuming that 0.01 von Mises strain would not induce significant changes in as-received texture, the work-contour at ĒURD = 0.01 would provide a reasonable estimation for the initial yield surface. Overall, regardless of the amount of deformation, the experimental flow stresses deviated significantly from the isotropic yield locus based on the von Mises yield criterion. The work contour at ĒURD = 0.01 is in good agreement with the prediction made by Hill48. At ĒURD = 0.05, the experimental flow stress starts deviating from that of ĒURD = 0.01 such that it agrees better with prediction made by VPSC.

Assuming that the work contour serves as yield locus as discussed in Refs. [39,40] and that associated flow rule is valid for the current IF steel, the locations of normal vectors (black arrows) to the VPSC work contour and the Hill48 yield locus are compared with the experimental strain vectors (gray arrows). In Fig. 8a, the locations of normal vectors by VPSC are compared with the experimental strain vectors. The corresponding stress locations for strain vectors of URD and UTD are slightly shifted towards the positive stress quadrant (i.e., Σ̅11 > 0 and Σ̅22 > 0). In case of Hill48, although it agrees well with the experimental stresses at ĒURD = 0.01 the corresponding normal locations largely deviate from the experimental observations for PSRD and PSTD.

It is interesting that the Hill48 model successfully captured the initial anisotropic yield locus with only two R-values obtained from the uniaxial tension tests. Yet, Hill48 was not capable of describing the strain-induced anisotropy observed in the IF steel sample since the isotropic phenomenological hardening description was used. Although the VPSC crystal plasticity model accounted for both the initial and strain-induced anisotropy by considering crystallographic texture, the current form of the micro-mechanical laws was not capable of fully capturing the anisotropic behavior of multiaxial strain hardening. The current form of VPSC modeling is widely practiced since only four hardening parameters (in Eq. (8)) are required as inputs in addition to the initial crystallographic texture. Nevertheless, since the current form of VPSC model did not satisfactorily explain the discrepancy with the experimental observations, a follow-up study based on an advanced model (such as [41,42]) might be required.

Overall, the experimental results successfully demonstrated that the isotropic hardening rule may not accurately represent the actual hardening behavior of the IF steel. Furthermore, none of the models including VPSC provide sufficiently accurate predictions to fully describe the anisotropic hardening behaviors of the IF steel in the strain range realized by the augmented Marciniak test. Yet, the experimental observations were limited by the measured drop in stress coincident with localization, so that an improvement in measurement technique is still desirable. The following potential improvements are noted as future work:

Measurement of stress during the entire displacement holding to quantify the stress relaxation;

Measurement of stress in various spatial locations of the subjected specimens;

Comparing with the case without interruption of displacement hold such as the one conducted in Ref. [43].

Investigation using a more advanced micro-mechanical description for the crystal plasticity modeling framework in order to capture the path-dependent anisotropy evident in the experimental data.

7. Conclusions

In this study, an augmented Marciniak recessed punch test was used with a combination of X-ray and DIC technique to obtain multiaxial stress/strain data for an IF steel sample. The experimental measurement was successfully conducted for three different multiaxial loading paths simply by adjusting the dimension of the flat samples. Although a stress drop correlated to strain localization limited the analyzed data, the experimental technique provided reasonable multiaxial constitutive data up to strain levels of 0.1 von Mises strain for plane strain and 0.2 von Mises strain for biaxial strain paths. When improvements to determining when localization occurs are made, additional analysis of the data may be possible.

The experimental results showed that the IF steel demonstrates a significant deviation from isotropic yield surface. Moreover, the experimental work contour demonstrated that the hardening behavior also deviates from the rule of isotropic work-hardening.

Hill's anisotropic yield criterion successfully described the initial anisotropic behavior. However, the multiaxial work contour after a von Mises strain of 0.05 deviates significantly from predictions made by Hill48. Predictions by the VPSC model were not in good agreement with the initial yield locus. Nonetheless, at a von Mises strain of 0.05 the predictions made by the VPSC mode was in better agreement with experimental observation in comparison with the yield locus predicted by Hill's anisotropic yield criterion. Beyond a von Mises strain of 0.1, predictions by VPSC tend to underestimate the multiaxial flow stress. Moreover, the associated flow rule (normality rule) was investigated for both Hill48 and the work contour predicted by VPSC. Neither of the two models provides reasonable predictive accuracy. Therefore, a more accurate constitutive model is required to describe the anisotropic experimental behaviors the IF steel at high strains.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge assistance of Mr. David Pitchure on the experiments using the Marciniak and X-ray systems. The careful review by Dr. Christopher Calhoun is kindly acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

Certain trade names and company products are identified in order to specify adequately the experimental procedure. In no case does such identification imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor does it imply that the products are necessarily the best for the purpose.

References

- 1.Hill R. A theory of the plastic bulging of a metal diaphragm by lateral pressure. Philos. Mag. 1950;41(322):1133–1142. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranta-Eskola AJ. Use of the hydraulic bulge test in biaxial tensile testing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1979;21(8):457–465. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird JE, Duncan JL. Strain hardening at high strain in aluminum alloys and its effect on strain localization. Metall. Trans. A. 1981;12(2):235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews J, Ellison E. A testing rig for cycling at high biaxial strains. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 1973;8(3):168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korkolis YP, Kyriakides S. Inflation and burst of anisotropic aluminum tubes for hydroforming applications. Int. J. Plasticity. 2008;24(3):509–543. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuwabara T, Sugawara F. Multiaxial tube expansion test method for measurement of sheet metal deformation behavior under biaxial tension for a large strain range. Int. J. Plasticity. 2012;45 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecker S. Experimental Studies of Yield Phenomena in Biaxially Loaded Metals. Los Alamos Scientific Lab., N. Mex. (USA) 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuwabara T, Ikeda S, Kuroda K. Measurement and analysis of differential work hardening in cold-rolled steel sheet under biaxial tension. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1998;80–81:517–523. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins DM, Mostafavi M, Todd RI, Connolley T, Wilkinson AJ. A synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of in situ biaxial deformation. Acta Mater. 2015;90:46–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Petegem S, Wagner J, Panzner T, Upadhyay MV, Trang TTT, Van Swygenhoven H. In-situ neutron diffraction during biaxial deformation. Acta Mater. 2016;105:404–416. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foecke T, Iadicola MA, Lin A, Banovic SW. A method for direct measurement of multiaxial stress-strain curves in sheet metal. Metal. Mater. Trans. A. 2007;38A(2):306–313. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iadicola MA, Foecke T, Banovic SW. Experimental observations of evolving yield loci in biaxially strained AA5754-O. Int. J. Plasticity. 2008;24(11):2084–2101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong Y, Gnäupel-Herold T, Barlat F, Iadicola M, Creuziger A, Lee M-G. Evaluation of biaxial flow stress based on Elasto-Viscoplastic Self-Consistent analysis of X-ray Diffraction Measurements. Int. J. Plasticity. 2015;66:103–118. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dölle H. The influence of multiaxial stress states, stress gradients and elastic anisotropy on the evaluation of (Residual) stresses by X-rays. J. Appl. Cryst. 1979;12:489–501. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brakman C. Residual stresses in cubic materials with orthorhombic or monoclinic specimen symmetry: influence of texture on [psi] splitting and non-linear behaviour. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1983;16(3):325–340. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gnäupel-Herold T, Iadicola MA, Creuziger AA, Foecke T, Hu L. Interpretation of diffraction data from in situ stress measurements during biaxial sheet metal forming. Materials Science Forum, Trans Tech Publications. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebensohn RA, Tomé CN. A self-consistent anisotropic approach for the simulation of plastic deformation and texture development of polycrystals: application to zirconium alloys. Acta Metal. Mater. 1993;41(9):2611–2624. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghavan KS. A simple technique to generate in-plane forming limit curves and selected applications. Metal. Mater. Trans. A. 1995;26(8):2075–2084. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marciniak Z, Kuczyński K, Pokora T. Influence of the plastic properties of a material on the forming limit diagram for sheet metal in tension. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1973;15(10):789–800. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gnäupel-Herold T, Creuziger AA, Iadicola M. A model for calculating diffraction elastic constants. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012;45(2):197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomota Y, Lukas P, Harjo S, Park JH, Tsuchida N, Neov D. In situ neutron diffraction study of IF and ultra low carbon steels upon tensile deformation. Acta Mater. 2003;51(3):819–830. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauk V. Structural and Residual Stress Analysis by Nondestructive Methods: Evaluation-application-assessment. Elsevier Science. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welzel U, Ligot J, Lamparter P, Vermeulen AC, Mittemeijer EJ. Stress analysis of polycrystalline thin films and surface regions by X-ray diffraction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2005;38(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welzel U, Mittemeijer EJ. Diffraction stress analysis of macroscopically elastically anisotropic specimens: on the concepts of diffraction elastic constants and stress factors. J. Appl. Phys. 2003;93(11):9001–9011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brakman C, Penning P. Non-linear diffraction strain vs sin2ψ phenomena in specimens exhibiting rolling-type texture. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 1988;44(2):163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong Y. DiffStress: a Tool to Analyze the Diffraction Stress Using Fully Anisotropic Diffraction Elastic Constants. 2015 https://github.com/usnistgov/DiffStress. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong Y, Iadicola M, Creuziger A, Gnäupel-Herold T. Uncertainty in flow stress measurements using X-ray diffraction for sheet metals subjected to large plastic deformation. doi: 10.1107/s1600576716013662. (Submitted to Journal of Applied Crystallography) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill R. A theory of the yielding and plastic flow of anisotropic metals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 1948;193(1033):281–297. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchinson JW. Bounds and self-consistent estimates for creep of polycrystalline materials. Proc. R. Soc. A. 1976;348:101–127. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molinari A, Canova GR, Ahzi S. A self consistent approach of the large deformation polycrystal viscoplasticity. Acta Metall. 1987;35(12):2983–2994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomé C, Canova GR, Kocks UF, Christodoulou N, Jonas JJ. The relation between macroscopic and microscopic strain hardening in F.C.C. polycrystals. Acta Metall. 1984;32(10):1637–1653. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelder JA, Mead R. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput. J. 1965;7:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones E, Oliphant T, Peterson P, et al. SciPy: Open Source Scientific Tools for Python. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaeben H, Hielscher R, Bachmann F. Texture analysis with mtex–free and open source software toolbox. Solid State Phenom. 2010;160:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill R. A self-consistent mechanics of composite materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 1965;13(4):213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeong Y. NIST Marciniak: Collection of Python Scripts that Analyze Data Generated by NIST's Augmented Marciniak Test Using DIC and X-ray. 2015 https://github.com/usnistgov/NIST_Marciniak. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeong Y. VPSC-FLD: Forming Limit Diagram Prediction and Yield Function Characterization Using VPSC Model. 2014 https://github.com/usnistgov/VPSC-FLD. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu L. Constitutive modeling of high strength steel sheets. Graduate Institute of Ferrous Technology, POSTECH. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill R, Hecker S, Stout M. An investigation of plastic flow and differential work hardening in orthotropic brass tubes under fluid pressure and axial load. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1994;31(21):2999–3021. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill R, Hutchinson J. Differential hardening in sheet metal under biaxial loading: a theoretical framework. J. Appl. Mech. 1992;59(2S):S1–S9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen W, Borodachenkova M, Tomé CN, Vincze G, Rauch EF, Barlat F, Grácio JJ. Mechanical behavior of Mg subjected to strain path changes: experiments and modeling. Int. J. Plast. 2015;73:171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitayama K, Tomé CN, Rauch EF, Gracio JJ, Barlat F. A crystallographic dislocation model for describing hardening of polycrystals during strain path changes. Application to low carbon steels. Int. J. Plast. 2012;46:54–69. [Google Scholar]

- 43.An K, Skorpenske HD, Stoica AD, Ma D, Wang X-L, Cakmak E. First in situ lattice strains measurements under load at VULCAN. Metal. Mater. Trans. A. 2011;42(1):95–99. [Google Scholar]