Abstract

Hypertension is a worldwide epidemic and global health concern as it is a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular diseases. A relationship between the immune system and its contributing role to the pathogenesis of hypertension has been long established, but substantial advancements within the last few years have dissected specific causal molecular mechanisms. This review will briefly examine these recent studies exploring the involvement of either innate or adaptive immunity pathways. Such pathways to be discussed include innate immunity factors such as antigen presenting cells and pattern recognition receptors, adaptive immune elements including T and B lymphocytes, and more specifically, the emerging role of T regulatory cells, as well as the potential of cytokines and chemokines to serve as signaling messengers connecting innate and adaptive immunity. Together, we summarize these studies to provide new perspective for what will hopefully lead to more targeted approaches to manipulate the immune system as hypertensive therapy.

Keywords: adaptive immunity, innate immunity, lymphocytes, antigen presenting cells, hypertension

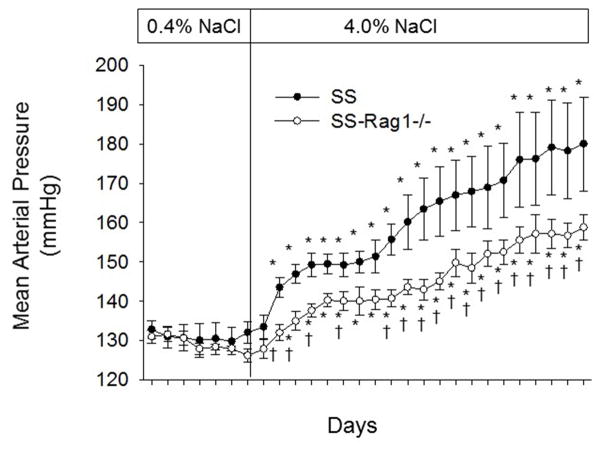

Over 50 years of evidence has established a prominent role for adaptive and innate immune mechanisms in the development of hypertension (HTN), vascular disease and renal disease1–6. Our lab’s interest in immune mechanisms in HTN arose from studies in which we observed that inflammation amplifies salt-sensitive hypertension (SSHTN) and end-organ damage in Dahl SS rats4. In Dahl SS rats, as in the clinical condition, HTN is greatly accelerated by a high salt diet4. Moreover, inflammation is a common feature of experimental and clinical HTN, with lymphocytes and macrophages localizing to regions of injury4,7–9. The amplifying effect of immune mechanisms on HTN are illustrated in Figure 1, in which we demonstrate the change in mean arterial blood pressure in Dahl SS rats and Dahl SS deficient in T and B lymphocytes (SS-Rag1−/−)10. The difference in the degree of salt-sensitive hypertension between the groups illustrates the role of immune mechanisms to amplify the HTN disease phenotype. As summarized below, a number of studies have illustrated the importance of adaptive and innate immune mechanisms in HTN; these mechanisms are the focus of this brief review.

Figure 1.

Development of salt-sensitive hypertension in Dahl SS rats (SS) and SS rats deficient in T- and B-lymphocytes due to the genetic deletion mutation in Rag1 (SS-Rag1−/−). * P<0.05 vs final day of low salt in the same group; † P<0.05 vs SS on the same day; n=4–5/group. (Reproduced with permission from Am J Physiol, 304:R407-414, 2013)

Targets of Adaptive Immunity

T and B Lymphocytes

The hallmark cell types of the adaptive immune system are T and B lymphocytes. T cells are activated after interaction with an antigen presenting cell (APC), then proliferate and differentiate into one of three effector subtypes: cytotoxic, helper, or regulatory T cells. Recent work shows an evolving role of the T cell in the development of HTN and chronic kidney disease. Studies utilizing genetic knockout of the recombination activating gene1 (RAG1) gene, which is essential for T and B cell maturation, in the mouse11 and later the rat10 have shown a clear attenuation in the development of angiotensin II (AngII)-induced and SSHTN (Figure 1). Genetic knockout of the CD247 gene, essential in T cell survival and receptor function, led to a severe depletion of T cells but left B cells intact. Compared to wild type rats, Dahl SS with CD247 knockout demonstrated an attenuation of SSHTN and end-organ damage12. Rodriguez-Iturbe et al also showed that systemic administration of the immunosuppressive agent mycophenolate mofetil led to a decrease in infiltrating immune cells in the kidney and a reduction in blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs)13. Clearly, affecting lymphocyte populations on a global scale has been shown to have dramatic effects in hypertensive animal models.

More recently, scientists have focused upon mechanisms of T cell survival and activation in HTN. One gene product required for T cell survival is the receptor tyrosine kinase TAM family member Axl. Korshunov et al first demonstrated attenuation of DOCA/salt-induced HTN in an Axl−/− mouse strain and also observed improved endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation compared to Axl+/+ 14. It was later discovered that Axl−/− mice exhibited severe depletion of peripheral blood T and B lymphocytes15, and adoptive transfer of Axl−/−Rag+/+ T cells into Axl+/+Rag−/− mice had significantly slower CD4+ repopulation than transfer of Axl+/+Rag+/+ T cells, underscoring the importance of Axl in T cell expansion.

Though adaptive immunity is important in the development of hypertension, the mechanisms activating these immune mechanisms are largely unknown. Seminal work published by the Harrison group revealed that the activation of T cells in AngII-induced HTN was dependent upon the production of highly reactive isoketals by dendritic cells16; moreover, the administration of various isoketal scavenging agents demonstrated a blunted hypertensive response. In addition, the isoketal scavenger 2-HOBA reduced AngII-induced renal fibrosis, renal T cell infiltration, IL-6 and IL-1β cytokine production, and T cell survival and proliferation. In an additional study, treatment with 2-HOBA or the antioxidant Tempol led to a decrease in production of IL-17A and IFNγ by T cells in tgsm/p22phox mice. Though it is well-established that reactive oxygen species (ROS) are linked to vascular damage in HTN17, these studies provide a link to adaptive immunity.

Similarly, work by Rodriguez-Iturbe and colleagues indicated that heat shock proteins (HSP), may also serve as an antigen triggering adaptive immunity in HTN18,19. Their work indicated that HSP70 could serve as an antigen mediating cellular immunity in experimental and human HTN. Studies by Macconi and colleagues demonstrated that proteolytic cleavage of albumin in proximal tubule cells could generate antigenic peptides20. The isoketal protein adducts, heat shock proteins, albumin cleavage products, or other molecules may serve as antigens which trigger the adaptive immune responses which amplify HTN and end organ damage.

Though the complete depletion of the T cell population has generated many interesting insights, the role of specific T cell subtypes has not been as deeply interrogated. In a study investigating the role of AngII on human T cells in a humanized mouse model, AngII treatment was found to increase total CD3+ and CD4+ T helper cells as well as CD45RO+ T memory cells in the kidney, which was abolished by the prevention of HTN through coadministration of hydrochlorthiazide (HZT) and hydralazine21. By controlling blood pressure, these experiments demonstrated that AngII did not directly affect the activation state of T cells. Trott et al also investigated the role of specific T cell subtypes in AngII as well as DOCA/salt-induced HTN and observed a blunted response in CD8−/− mice but not in MHCII−/− or CD4−/− mice22. In adoptive T cell transfer experiments into Rag1−/− mice, transfer of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells significantly increased blood pressure, whereas transfer of CD4+/CD25− T cells did not. Although these results implicate a more direct effect of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells on the hypertensive phenotype, the role of CD4+ helper T cells needs to be explored more thoroughly.

Compared to T cells, the contribution of B cells to hypertensive pathology is being investigated at a much slower pace despite clear evidence that antibodies are elevated in patients with essential HTN23. Chan et al explicitly investigated the role of B cells in AngII-induced HTN, and found AngII increased B cell activation, the number of plasmablasts and plasma cells, and serum IgG24. B cell activating factor receptor deficient (BAFF-R−/−) mice that lack B cells did not exhibit the same increase in blood pressure observed in WT mice in response to AngII, but importantly, adoptive transfer of B cells into BAFF-R−/− mice restored AngII-induced HTN. In apparent contradiction to the study by Trott et al, who found an increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the kidney, analysis of T cell subsets revealed no change in CD8+ cells and an increase in CD4+ cells in the aorta upon AngII administration. The integral role of B cells in adaptive immunity as well as understanding its crosstalk with T cells will be important in the holistic investigation of HTN pathogenesis.

T regulatory cells

T regulatory cells (Tregs) are a specialized subset of T cells that are responsible for the maintenance of immune homeostasis and self-tolerance25. In humans, Tregs comprise about 5–10% of peripheral CD4+ T cells, and they express CD4+, CD25+ and forkhead/winged helix transcription factor P3 (FoxP3)26. FoxP3 is a major regulatory gene required for the development and regulatory function of Tregs27. Tregs are reported to play a pivotal role of suppression of both the innate and the adaptive immune system. Through multiple mechanisms, Tregs turn off immune responses of T cells and dendritic cells by suppression of T cell proliferation and cytokine production as well as the release of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β28. While Tregs have been identified as protectors against autoimmune and inflammatory diseases29, the role of Tregs in the progression of cardiovascular diseases, including HTN, is not sufficiently understood.

Tregs have been reported to be protective against increases in blood pressure in various animal models of HTN, such as the Dahl SS rat. Using zinc-finger nuclease-mediated genetic mutation, a 6 base pair deletion in the highly conserved region of the SH2B3 gene resulted in an attenuation of HTN in response to the high salt diet relative to Dahl SS rats. Dahl SS rats with a mutation in the SH2B3 gene had an increased percentage of Tregs in both the spleen and circulation compared to Dahl SS rats30. Additionally, Viel et al demonstrated that the presence of the Brown Norway rat chromosome 2 on the Dahl SS background in the consomic rat (SSBN2) resulted in an upregulation of Treg markers and activity as well as other anti-inflammatory markers, IL-10 and TGF-β31. These results suggest that the increased number of Tregs provided protection from deleterious high salt-induced effects normally seen in Dahl SS rats.

Mian et al took a mechanistic approach to demonstrate the protective nature of Tregs and their interplay within the immune and cardiovascular systems during HTN. They examined the protective role of Tregs in an AngII-induced model of HTN. In Rag1−/− mice infused with AngII and coinjected with Tregs, blood pressure was comparable to vehicle-treated controls. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of T cells from Scurfy mice, which are deficient in Tregs due to a missense mutation in the FoxP3 gene, into Rag1−/− mice also resulted in the onset of AngII induced HTN32. Yet, coinjection of Tregs into these Rag1−/− mice adoptively transferred with T cells from Scurfy mice only delayed the onset of AngII induced HTN, suggesting that Tregs alone might not be sufficient to prevent HTN in this model. When endothelial function was examined in secondary mesenteric vessels of these animals, the mice that received T cells from Scurfy mice exhibited AngII-induced endothelial dysfunction compared to WT mice. Furthermore, when animals were coinjected with Tregs, endothelial dysfunction was reduced but not normalized to control mice32. The cotransfer of Tregs blunted the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and infiltration of immune cells within the mesenteric vessels and the cortical regions of the kidney; however, it did not prohibit the development of HTN and endothelial dysfunction.

A therapeutic role for Tregs has also been demonstrated in the treatment of preeclampsia, a pregnancy specific form of HTN. The immune system is implicated in the pathology of preeclampsia with an imbalance of Tregs in favor of proinflammatory CD4+ T cells, leading to proinflammatory cytokine production and chronic inflammation33. In the reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rat model of preeclampsia, circulating CD4+ T cells are elevated in rats at day 19 of gestation compared to normal pregnant animals while there was a significant decrease in circulating Tregs in the RUPP rats34. Further studies demonstrated that supplementation of Tregs from normal pregnant rats into RUPP rats normalized levels of circulating Tregs and attenuated HTN35. While Treg supplementation did not affect IL-10 levels, TGFβ levels were increased in RUPP supplemented rats to levels comparable with normal pregnant rats. Adoptive transfer of normal pregnant Tregs also blunted the inflammatory response by decreasing circulating levels of IL-17 and TNFα in RUPP rats35. These studies together establish that Tregs offer varying degrees of protection against the development of HTN in a number of animal models, and further experiments are required to determine the mechanism by which Tregs are a promising therapeutic target for HTN.

Cytokines and chemokines

In order for the adaptive immune system to be effective, signals are conveyed through cytokines and chemokines; this section will discuss some of the major players being investigated. T-bet−/− mice, characterized by impaired production of TNFα and IFNγ and the inability to elicit a Th1 response, retained the same hypertensive response to AngII as WT mice but lacked the associated renal damage assessed by nephrin excretion36. Delineating the effects of these two cytokines, TNFα−/− mice displayed attenuated AngII-induced increases in blood pressure, albuminuria, nephrinuria, and renal histological damage while IFNγ−/− mice were phenotypically similar to WT mice36, designating TNFα as a major cytokine contributing to AngII-induced HTN and renal end-organ damage. Renal transplantation experiments attributed these protective effects in TNFα−/− mice to increased renal eNOS expression and NO bioavailability.

Interleukins also play a major role in cytokine signaling and their expression varies by cell type. Chatterjee et al investigated whether treatment with anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10, both secreted by Th2 cells, could prevent HTN in pregnant mice37. Treatment with IL-4, IL-10, or IL-4/IL-10 in combination reduced Poly I:C-induced preeclampsia, restored aortic acetylcholine-mediated relaxation, and returned expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IFNγ, TNFα, and TGFβ back to control levels. However, only the combination treatment of IL-4/IL-10 prevented proteinuria, the increased incidence of fetal demise, and the increase in T cells and dendritic cells observed during preeclampsia. This evidence shows the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-4 and combination IL-4/IL-10 treatment in a model of preeclampsia. Other interleukins known to be secreted by both adaptive and innate immune cells, like IL-6 and IL-1β, will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

As discussed, Tregs contribute to immune response modulation by suppression of proliferation and signaling; however, T-helper 17 (Th17) cells act in opposition, upregulating pro-inflammatory mechanisms. Upon stimulation, primarily through IL-23R and IL-1R, Th17 cells are activated to produce IL-17 along with IL-21 and IL-22. Studies by Wu et al38 have demonstrated that in IL-23R−/− cells, downstream serum glucocorticoid kinase-1 (SGK1) is critical for Th17 function. IL-23R signaling through SGK1 also appears to contribute to the increase of Th17 cells in response to a high salt diet, which is consistent with SGK1 being involved in NaCl transport39. Kleinewietfeld et al have similarly shown that stimulated Th17 cells demonstrate increased IL-17 production and in vitro pathogenicity in response to increased salt concentration. In vivo, high salt diet also increased IL-17a production and the clinical score of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis40. Madhur et al worked to translate the role of IL-17 in an AngII-induced model of HTN41. AngII treatment increased T cell production of IL-17 and the percentage of circulating IL-17-producing CD4+ cells. IL-17−/− mice had an attenuation in AngII-induced HTN and superoxide production. In addition, IL-17−/− mice had phenylephrine-induced vascular contraction comparable to untreated mice and preserved endothelium-dependent vasodilation. These KO mice also had a complete attenuation of aortic infiltration of CD45+ and CD3+ T cells. In addition, their group found dramatic increases in serum IL-17 in human hypertensives compared to normotensives, validating this paradigm in human HTN.

In SHRs, AngII treatment of vascular smooth muscle cells suppressed expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Administration of the chemokine CCL5, or RANTES, resulted in upregulation of IL-10, and attenuation of AngII-induced vascular dysfunction and systolic blood pressure, suggesting a protective, antihypertensive role for CCL542. However, a more recent contradicting study demonstrated protection from AngII-induced endothelial dysfunction and reduced vascular and perivascular adipose tissue T cell infiltration in RANTES−/− mice43. AngII-infused RANTES−/− mice have decreased infiltrating IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells as well as CD3+CD4−CD8− T cells that have an impaired ability to produce IFNγ compared to WT mice. Although the specific role of such signaling messengers remains to be clearly identified, cytokines and chemokines provide more finely tuned immune-based therapeutic targets than systemic downregulation, mitigating some, but not all, of the risks associated with immunosuppressive treatments.

Targets of Innate Immunity

Antigen Presenting Cells

While many studies have documented the contribution of the adaptive immune response in HTN, it is classically understood that activation of innate immunity through APCs is a required and initiating step. This was substantiated by experiments performed by Vinh et al, which demonstrated that T cell activation and the development of DOCA/salt HTN was dependent upon T cell coreceptor CD28 costimulation by APC B7 ligands44. Furthermore, depletion of APCs such as macrophages and neutrophils, or inhibition of their accumulation has been shown to impair disease progression in multiple models of experimental HTN, including the RUPP, DOCA/salt, and AngII-induced models of HTN45–47. As previously mentioned, work by Harrison’s group suggests the production of highly reactive isoketals by dendritic cells during HTN are the mechanistic link to T cell stimulation16. High salt has been shown to directly activate macrophages, which may be helpful for antimicrobial functions during infection48, but pathogenic salt stimulation may cause an overall imbalance in immune homeostasis by detrimentally promoting T cell activation characteristically observed during salt-sensitive HTN49,50. Additionally, salt has recently been demonstrated to promote proinflammatory Th17 cells and suppress anti-inflammatory Tregs51. The established regulation of T cell activation by these various APCs makes these early innate immunity components attractive targets for hypertensive therapeutic interventions.

Pattern Recognition Receptors: TLRs

Innate immune cells utilize pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to recognize pathogens and threats to the host, and thus activation of PRRs is an early occurring step. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a well-characterized family of membrane-bound PRRs found either on the surface or in the lumen of intracellular vesicles of macrophages, dendritic cells, and mast cells52. Recent studies have focused on specific members of the TLR family, including TLR4, TLR9, and TLR2. TLR4 expression is upregulated in experimental models of AngII and L-NAME-induced HTN53–54; importantly, TLR4 mRNA upregulation also occurs in peripheral monocytes of human hypertensive patients compared to normotensives55. This upregulation is functionally important, since TLR4 inhibition by anti-TLR4 antibody has been shown by multiple laboratories to augment vascular contractility, vascular inflammation, and oxidative stress in SHRs, ultimately preventing experimental HTN53,56,57. TLR9, which recognizes mitochondrial DNA, a product of tissue damage, is also upregulated in the circulation of SHRs, and treatment with TLR9 inhibitory oligodinucleotide ODN2088 resulted in a reduction in systolic blood pressure58. This follows with the studies performed by Rodrigues et al in TLR9−/− mice, implicating TLR9 in the cardiac autonomic and baroreflex control of arterial blood pressure59. A previously undiscovered link between TLR2 and NLRP3 in renal tubular epithelial cells was recently revealed, where TLR2 ligands induced NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent necrosis, demonstrating the crosstalk between TLRs and other PRRs in the kidney60. Interestingly, the same aforementioned hypertensive patients with higher levels of TLR4 mRNA in peripheral monocytes experienced a significantly downregulation of both TLR2 and TLR4 mRNA in response to intensive SBP-lowering treatments, perhaps suggesting a forward feeding mechanism between increased pressure and immune system activation55. These recent reports clearly demonstrate an integral role for TLRs in controlling the severity of the pathogenic response to hypertensive stimuli and provide a strong rationale for the potential benefit of clinical TLR pharmacologic inhibition.

Pattern Recognition Receptors: NLRs

Intracellular NOD-like receptors (NLRs) are another family of PRRs, with the most characterized NLR being the NLRP3 inflammasome. It has recently gained notoriety for its diverse recognition of exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) derived from disease, and consists of the NLRP3 sensory component, the adaptor protein ASC, and the effector protein caspase-1. When stimulated, these intracellular components oligomerize into large complexes and initiate the cascade leading to IL-1β maturation and eventual activation of adaptive immunity. The presence of a human NLRP3 gene polymorphism that is associated with increased blood pressure suggests the clinical relevance of further exploring the role of this particular PRR in HTN61. Preclinical studies in preeclampsia demonstrated protection from AngII-induced HTN in NLRP3−/− but not ASC−/− pregnant mice62. This follows with clinical data in isolated monocytes from human preeclamptic pregnant women that were stimulated with uric acid which revealed significantly higher gene expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome components when compared to those isolated from normotensive controls63.

A role of the NLRP3 inflammasome has also been shown in aldosterone-induced renal fibrosis and HTN, where in vivo aldosterone administration promoted renal fibrosis via inflammasome activation, but bone marrow transplantation of ASC-deficient mice highlighted the contribution of macrophage-derived inflammasomes in mediating this pathology64. Furthermore, ASC−/− mice or mice treated with NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 were protected from 1K/DOCA/salt-induced HTN, inflammation, and fibrosis65. NLRP3 inflammasome involvement has also been established in animal models of SSHTN and was first shown by Qi et al where Dahl SS rats fed a high salt diet resulted in elevated NLRP3 and IL-1β in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), which was inhibited by NFκB blockade, indicating the importance of localized PVN NFκB activation in the sympathoexcitation that leads to HTN in response to high salt66. More recently NLRP3 inflammasome upregulation has also been demonstrated in the renal medulla of Dahl SS rats fed high salt and administration of caspase-1 inhibitor Ac-YVAD-cmk prevented SSHTN67.

Cytokines IL-1β and IL-6

IL-1β, a product of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, is a potent proinflammatory cytokine linked to a wide number of immunological pathologies and its release is typically associated with cells of the innate immune system. However, it is unclear whether this cytokine is involved in potentiating HTN specifically or is perhaps simply a biomarker of disease progression68. Interestingly, multiple groups have demonstrated IL-1β inhibition or IL-1 receptor blockade to have protective, antihypertensive effects69–71. This is an incredibly exciting avenue of study since there exist IL-1 blockers and receptor antagonists clinically approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Another cytokine secreted by cells of both adaptive and innate immunity origin is IL-6. Increased IL-6 has been observed in cardiac tissue of SHRs54, and AngII has been shown to stimulate macrophage-derived IL-6 which drives intrarenal RAS activity in proximal tubular cells and the eventual progression of HTN and renal injury72. Recent studies in our laboratory have focused on the role of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in the development of SSHTN73. Dahl SS rats on a high salt diet and treated with an anti-IL-6 antibody had lower mean arterial pressure, a later onset of HTN, lower albumin excretion rate, less glomerular sclerosis and protein casts, and a decrease in infiltrating leukocytes. These protective effects of IL-6 blockade were coupled with reductions in monocyte/macrophage infiltration but not lymphocyte infiltration, perhaps implicating a targeted effect of IL-6 on these innate immune cells and in the progression of SSHTN and kidney damage.

Implications

Recent reports indicate that only 54% of hypertensive patients in 2009–2012 had their hypertension under control74. Outside of dietary and lifestyle changes, pharmacological agents, which primarily treat the symptoms rather than the cause of HTN, have been the first line of therapy, but these approaches are are not fully effective74. This indicates a clear need to identify new and improved treatment strategies; this review, among others, summarizes the role of the immune system and inflammation in the progression of HTN and end-organ disease. As others have discussed75, translating this work to clinical investigation and treatment is difficult, as immunosuppressant agents and cytokine inhibitors that may be used to treat HTN will likely have the same unwanted side-effects that immunosuppressive treatments have in other diseases. It is the goal of this research to identify molecular mechanisms unique to HTN that can be used as targeted therapies.

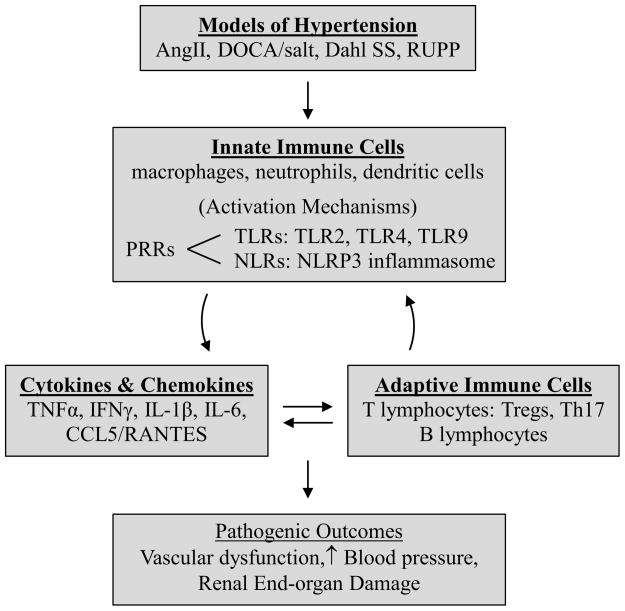

In brief, the field of immunity in HTN is rapidly progressing and evolving. A summary of this brief review is provided in a graphical abstract (Figure 2) which represents the interplay between immune mechanisms and disease progression in animal models of HTN. The studies summarized in this review demonstrate the continuing pursuit for more specific molecular targets that can be manipulated to yield the best clinical outcomes. This success will likely be determined by the growing understanding of the mediators, mechanisms, and interactions of both the adaptive and innate arms of the immune system in HTN.

Figure 2.

Innate and adaptive immunity targets discussed in this review.

Abbreviations: AngII: Angiotensin II, CCL5/RANTES: C-C chemokine ligand 5/Regulated upon Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed, and Secreted, Dahl SS: Dahl Salt-Sensitive Rat, DOCA/salt: deoxycorticosterone acetate/salt, IFNγ: interferon γ, IL-1β: interleukin-1β, IL-6: interleukin-6, NLRs: NOD-like receptors, NLRP3: nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (Nod)-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3, PRRs: pattern recognition receptors, RUPP: reduced uterine perfusion pressure, Th17: IL-17-producing T cells, TLRs: Toll-like receptors, TNFα: tumor necrosis factor α, Tregs: T regulatory cells

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: DK96859, HL116264, 15SFRN2391002, AHA16POST29900004

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Renal infiltration of immunocompetent cells: cause and effect of sodium-sensitive hypertension. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2010;14:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s10157-010-0268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A, Weyand CM. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 57:132–140. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Synapses, Signals, CDs, and Cytokines Interactions of the Autonomic Nervous System and Immunity in Hypertension. Circulation Research. 2012;111:1113–1116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.278408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattson DL. Infiltrating immune cells in the kidney in salt-sensitive hypertension and renal injury. Am J Physiol. 2014;307:F499–F508. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00258.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan MJ. An Update on Immune System Activation in the Pathogenesis of Hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62:226–230. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.00603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiffrin EL. T lymphocytes: a role in hypertension? Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2010;19:181–186. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283360a2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughson MD, Gobe GC, Hoy WE, Manning RD, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF. Associations of glomerular number and birth weight with clinicopathological features of African Americans and whites. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:18–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Central and peripheral mechanisms of T-lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circulation research. 2010;107:263–270. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozawa Y, Kobori H, Suzaki Y, Navar LG. Sustained renal interstitial macrophage infiltration following chronic angiotensin II infusions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F330–339. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00059.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattson DL, Lund H, Guo C, Rudemiller N, Geurts AM, Jacob H. Genetic mutation of recombination activating gene 1 in dahl salt-sensitive rats attenuates hypertension and renal damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R407–414. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00304.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the t cell in the genesis of angiotensin ii induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudemiller N, Lund H, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Mattson DL. PhysGen Knockout P. Cd247 modulates blood pressure by altering t-lymphocyte infiltration in the kidney. Hypertension. 2014;63:559–564. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Nava M, Bonet L, Chavez M, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ, Pons HA. Reduction of renal immune cell infiltration results in blood pressure control in genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F191–201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0197.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korshunov VA, Daul M, Massett MP, Berk BC. Axl mediates vascular remodeling induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;50:1057–1062. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batchu SN, Hughson A, Wadosky KM, Morrell CN, Fowell DJ, Korshunov VA. Role of axl in t-lymphocyte survival in salt-dependent hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1638–1646. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirabo A, Fontana V, de Faria AP, Loperena R, Galindo CL, Wu J, Bikineyeva AT, Dikalov S, Xiao L, Chen W, Saleh MA, Trott DW, Itani HA, Vinh A, Amarnath V, Amarnath K, Guzik TJ, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ, Shyr Y, Chen SC, Mernaugh RL, Laffer CL, Elijovich F, Davies SS, Moreno H, Madhur MS, Roberts J, 2nd, Harrison DG. Dc isoketal-modified proteins activate t cells and promote hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4642–4656. doi: 10.1172/JCI74084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montezano AC, Tsiropoulou S, Dulak-Lis M, Harvey A, de Camargo LL, Touyz RM. Redox signaling, nox5 and vascular remodeling in hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24:425–433. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pons H, Ferrebuz A, Quiroz Y, Romero-Vasquez F, Parra G, Johnson RJ, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Immune reactivity to heat shock protein 70 expressed in the kidney is cause of salt-sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304:F289–F299. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00517.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;67:477–483. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macconi D, Chiabrando C, Schiarea S, Aiello S, Cassis L, Gagliardini E, Noris M, Buelli S, Zoja C, Corna D, Mele C, Fanelli R, Remuzzi G, Benigni A. Proteasomal processing of albumin by renal dendritic cells generates antigenic peptides. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:123–130. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itani HA, McMaster WG, Jr, Saleh MA, Nazarewicz RR, Mikolajczyk TP, Kaszuba AM, Konior A, Prejbisz A, Januszewicz A, Norlander AE, Chen W, Bonami RH, Marshall AF, Poffenberger G, Weyand CM, Madhur MS, Moore DJ, Harrison DG, Guzik TJ. Activation of human t cells in hypertension: Studies of humanized mice and hypertensive humans. Hypertension. 2016;68:123–132. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trott DW, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Saleh MA, Itani H, Norlander AE, Wu J, Goldstein A, Arendshorst WJ, Madhur MS, Chen W, Li CI, Shyr Y, Harrison DG. Oligoclonal cd8+ t cells play a critical role in the development of hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:1108–1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebringer A, Doyle AE. Raised serum igg levels in hypertension. Br Med J. 1970;2:146–148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5702.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan CT, Sobey CG, Lieu M, Ferens D, Kett MM, Diep H, Kim HA, Krishnan SM, Lewis CV, Salimova E, Tipping P, Vinh A, Samuel CS, Peter K, Guzik TJ, Kyaw TS, Toh BH, Bobik A, Drummond GR. Obligatory role for b cells in the development of angiotensin ii-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;66:1023–1033. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaczorowski M, Jutel M. Human t regulatory cells: On the way to cognition. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2013;61:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s00005-013-0217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hori S, Sakaguchi S. Foxp3: A critical regulator of the development and function of regulatory t cells. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:745–751. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morikawa H, Sakaguchi S. Genetic and epigenetic basis of treg cell development and function: From a foxp3-centered view to an epigenome-defined view of natural treg cells. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:192–205. doi: 10.1111/imr.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cools N, Ponsaerts P, Van Tendeloo VF, Berneman ZN. Regulatory t cells and human disease. Clin Dev Immunol. 2007;2007:89195. doi: 10.1155/2007/89195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raphael I, Nalawade S, Eagar TN, Forsthuber TG. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine. 2015;74:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudemiller NP, Lund H, Priestley JR, Endres BT, Prokop JW, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Cohen EP, Mattson DL. Mutation of sh2b3 (lnk), a genome-wide association study candidate for hypertension, attenuates dahl salt-sensitive hypertension via inflammatory modulation. Hypertension. 2015;65:1111–1117. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viel EC, Lemarie CA, Benkirane K, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Immune regulation and vascular inflammation in genetic hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H938–944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00707.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mian MO, Barhoumi T, Briet M, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Deficiency of t-regulatory cells exaggerates angiotensin ii-induced microvascular injury by enhancing immune responses. J Hypertens. 2016;34:97–108. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harmon AC, Cornelius DC, Amaral LM, Faulkner JL, Cunningham MW, Jr, Wallace K, LaMarca B. The role of inflammation in the pathology of preeclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:409–419. doi: 10.1042/CS20150702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace K, Richards S, Dhillon P, Weimer A, Edholm ES, Bengten E, Wilson M, Martin JN, Jr, LaMarca B. Cd4+ t-helper cells stimulated in response to placental ischemia mediate hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2011;57:949–955. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornelius DC, Amaral LM, Harmon A, Wallace K, Thomas AJ, Campbell N, Scott J, Herse F, Haase N, Moseley J, Wallukat G, Dechend R, LaMarca B. An increased population of regulatory t cells improves the pathophysiology of placental ischemia in a rat model of preeclampsia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;309:R884–891. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00154.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Patel MB, Griffiths R, Mao A, Song YS, Karlovich NS, Sparks MA, Jin H, Wu M, Lin EE, Crowley SD. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha produced in the kidney contributes to angiotensin ii-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:1275–1281. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Seerangan G, Tobin RP, Kopriva SE, Newell-Rogers MK, Mitchell BM. Cotreatment with interleukin 4 and interleukin 10 modulates immune cells and prevents hypertension in pregnant mice. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:135–142. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu C, Yosef N, Thalhamer T, Zhu C, Xiao S, Kishi Y, Regev A, Kuchroo V. Induction of pathogenic Th17 cells by inducible salt sensing kinase SGK1. Nature. 2013;35:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature11984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diakov A, Korbmacher C. A novel pathway of epithelial sodium channel activation involves a serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase consensus motif in the C terminus of the channel’s alpha-subunit. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38134–38142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA, Muller DN, Hafler DA. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic Th17 cells. Nature. 2013;496:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Interleukin 17 promoes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2010;55:500. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim HY, Cha HJ, Kim HS. Ccl5 upregulates il-10 expression and partially mediates the antihypertensive effects of il-10 in the vascular smooth muscle cells of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:666–674. doi: 10.1038/hr.2015.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mikolajczyk TP, Nosalski R, Szczepaniak P, Budzyn K, Osmenda G, Skiba D, Sagan A, Wu J, Vinh A, Marvar PJ, Guzik B, Podolec J, Drummond G, Lob HE, Harrison DG, Guzik TJ. Role of chemokine rantes in the regulation of perivascular inflammation, t-cell accumulation, and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. FASEB J. 2016;30:1987–1999. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500088R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vinh A, Chen W, Blinder Y, Weiss D, Taylor WR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, Harrison DG, Guzik TJ. Inhibition and genetic ablation of the b7/cd28 t-cell costimulation axis prevents experimental hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:2529–2537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regal JF, Lillegard KE, Bauer AJ, Elmquist BJ, Loeks-Johnson AC, Gilbert JS. Neutrophil depletion attenuates placental ischemia-induced hypertension in the rat. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thang LV, Demel SL, Crawford R, Kaminski NE, Swain GM, Van Rooijen N, Galligan JJ. Macrophage depletion lowers blood pressure and restores sympathetic nerve alpha2-adrenergic receptor function in mesenteric arteries of doca-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1186–1197. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00283.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore JP, Vinh A, Tuck KL, Sakkal S, Krishnan SM, Chan CT, Lieu M, Samuel CS, Diep H, Kemp-Harper BK, Tare M, Ricardo SD, Guzik TJ, Sobey CG, Drummond GR. M2 macrophage accumulation in the aortic wall during angiotensin ii infusion in mice is associated with fibrosis, elastin loss, and elevated blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H906–917. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00821.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jantsch J, Schatz V, Friedrich D, Schroder A, Kopp C, Siegert I, Maronna A, Wendelborn D, Linz P, Binger KJ, Gebhardt M, Heinig M, Neubert P, Fischer F, Teufel S, David JP, Neufert C, Cavallaro A, Rakova N, Kuper C, Beck FX, Neuhofer W, Muller DN, Schuler G, Uder M, Bogdan C, Luft FC, Titze J. Cutaneous na+ storage strengthens the antimicrobial barrier function of the skin and boosts macrophage-driven host defense. Cell Metab. 2015;21:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binger KJ, Gebhardt M, Heinig M, Rintisch C, Schroeder A, Neuhofer W, Hilgers K, Manzel A, Schwartz C, Kleinewietfeld M, Voelkl J, Schatz V, Linker RA, Lang F, Voehringer D, Wright MD, Hubner N, Dechend R, Jantsch J, Titze J, Muller DN. High salt reduces the activation of il-4- and il-13-stimulated macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4223–4238. doi: 10.1172/JCI80919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang WC, Zheng XJ, Du LJ, Sun JY, Shen ZX, Shi C, Sun S, Zhang Z, Chen XQ, Qin M, Liu X, Tao J, Jia L, Fan HY, Zhou B, Yu Y, Ying H, Hui L, Liu X, Yi X, Liu X, Zhang L, Duan SZ. High salt primes a specific activation state of macrophages, m(na) Cell Res. 2015;25:893–910. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hernandez AL, Kitz A, Wu C, Lowther DE, Rodriguez DM, Vudattu N, Deng S, Herold KC, Kuchroo VK, Kleinewietfeld M, Hafler DA. Sodium chloride inhibits the suppressive function of foxp3+ regulatory t cells. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4212–4222. doi: 10.1172/JCI81151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawai T, Akira S. The roles of tlrs, rlrs and nlrs in pathogen recognition. Int Immunol. 2009;21:317–337. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Batista PR, Palacios R, Martin A, Hernanz R, Medici CT, Silva MA, Rossi EM, Aguado A, Vassallo DV, Salaices M, Alonso MJ. Toll-like receptor 4 upregulation by angiotensin ii contributes to hypertension and vascular dysfunction through reactive oxygen species production. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eissler R, Schmaderer C, Rusai K, Kuhne L, Sollinger D, Lahmer T, Witzke O, Lutz J, Heemann U, Baumann M. Hypertension augments cardiac toll-like receptor 4 expression and activity. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:551–558. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marketou ME, Kontaraki JE, Zacharis EA, Kochiadakis GE, Giaouzaki A, Chlouverakis G, Vardas PE. Tlr2 and tlr4 gene expression in peripheral monocytes in nondiabetic hypertensive patients: The effect of intensive blood pressure-lowering. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14:330–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bomfim GF, Dos Santos RA, Oliveira MA, Giachini FR, Akamine EH, Tostes RC, Fortes ZB, Webb RC, Carvalho MH. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to blood pressure regulation and vascular contraction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:535–543. doi: 10.1042/CS20110523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bomfim GF, Echem C, Martins CB, Costa TJ, Sartoretto SM, Dos Santos RA, Oliveira MA, Akamine EH, Fortes ZB, Tostes RC, Webb RC, Carvalho MH. Toll-like receptor 4 inhibition reduces vascular inflammation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Life Sci. 2015;122:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy CG, Wenceslau CF, Goulopoulou S, Ogbi S, Baban B, Sullivan JC, Matsumoto T, Webb RC. Circulating mitochondrial DNA and toll-like receptor 9 are associated with vascular dysfunction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107:119–130. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodrigues FL, Silva LE, Hott SC, Bomfim GF, da Silva CA, Fazan R, Jr, Resstel LB, Tostes RC, Carneiro FS. Toll-like receptor 9 plays a key role in the autonomic cardiac and baroreflex control of arterial pressure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:R714–723. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00150.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kasimsetty SG, DeWolf SE, Shigeoka AA, McKay DB. Regulation of tlr2 and nlrp3 in primary murine renal tubular epithelial cells. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;127:119–123. doi: 10.1159/000363208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kunnas T, Maatta K, Nikkari ST. Nlr family pyrin domain containing 3 (nlrp3) inflammasome gene polymorphism rs7512998 (c>t) predicts aging-related increase of blood pressure, the tamrisk study. Immun Ageing. 2015;12:19. doi: 10.1186/s12979-015-0047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shirasuna K, Karasawa T, Usui F, Kobayashi M, Komada T, Kimura H, Kawashima A, Ohkuchi A, Taniguchi S, Takahashi M. Nlrp3 deficiency improves angiotensin ii-induced hypertension but not fetal growth restriction during pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2015;156:4281–4292. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matias ML, Romao M, Weel IC, Ribeiro VR, Nunes PR, Borges VT, Araujo JP, Jr, Peracoli JC, de Oliveira L, Peracoli MT. Endogenous and uric acid-induced activation of nlrp3 inflammasome in pregnant women with preeclampsia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kadoya H, Satoh M, Sasaki T, Taniguchi S, Takahashi M, Kashihara N. Excess aldosterone is a critical danger signal for inflammasome activation in the development of renal fibrosis in mice. FASEB J. 2015;29:3899–3910. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-271734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krishnan SM, Dowling JK, Ling YH, Diep H, Chan CT, Ferens D, Kett MM, Pinar A, Samuel CS, Vinh A, Arumugam TV, Hewitson TD, Kemp-Harper BK, Robertson AA, Cooper MA, Latz E, Mansell A, Sobey CG, Drummond GR. Inflammasome activity is essential for one kidney/deoxycorticosterone acetate/salt-induced hypertension in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:752–765. doi: 10.1111/bph.13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qi J, Yu XJ, Shi XL, Gao HL, Yi QY, Tan H, Fan XY, Zhang Y, Song XA, Cui W, Liu JJ, Kang YM. Nf-kappab blockade in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus inhibits high-salt-induced hypertension through nlrp3 and caspase-1. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2016;16:345–354. doi: 10.1007/s12012-015-9344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu Q, Li XX, Wang W, Hu J, Li PL, Conley SM, Li N. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation inhibited high salt-induced activation of the nlrp3 inflammasome in the renal medulla in dahl s rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00344.2015. ajprenal 00344 02015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krishnan SM, Sobey CG, Latz E, Mansell A, Drummond GR. Il-1beta and il-18: Inflammatory markers or mediators of hypertension? Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:5589–5602. doi: 10.1111/bph.12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Southcombe JH, Redman CW, Sargent IL, Granne I. Interleukin-1 family cytokines and their regulatory proteins in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;181:480–490. doi: 10.1111/cei.12608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qi J, Zhao XF, Yu XJ, Yi QY, Shi XL, Tan H, Fan XY, Gao HL, Yue LY, Feng ZP, Kang YM. Targeting interleukin-1 beta to suppress sympathoexcitation in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in dahl salt-sensitive hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2016;16:298–306. doi: 10.1007/s12012-015-9338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang J, Rudemiller NP, Patel MB, Karlovich NS, Wu M, McDonough AA, Griffiths R, Sparks MA, Jeffs AD, Crowley SD. Interleukin-1 receptor activation potentiates salt reabsorption in angiotensin ii-induced hypertension via the nkcc2 co-transporter in the nephron. Cell Metab. 2016;23:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O’Leary R, Penrose H, Miyata K, Satou R. Macrophage-derived il-6 contributes to ang ii-mediated angiotensinogen stimulation in renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310:F1000–1007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00482.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hashmat S, Rudemiller NP, Lund H, Abais-Battad JM, Van Why SK, Mattson DL. Interleukin-6 inhibition attenuates hypertension and associated renal damage in dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00594.2015. ajprenal 00594 02015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das Sr, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gooch JL, Sharma AC. Targeting the immune system to treat hypertension: where are we? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:473–9. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]