Abstract

Helicobacter pylori’s unique ability to colonize and survive in the acidic environment of the stomach is critically dependent on uptake of urea through the urea channel, HpUreI. Hence, HpUreI may represent a promising target for the development of specific drugs against this human pathogen. To obtain insight into the structure/function relationship of this channel, we have developed conditions for the high-yield expression and purification of stable recombinant HpUreI that allowed its detailed kinetic characterization in solubilized form and reconstituted into liposomes. Detergent-solubilized HpUreI forms homo-trimer, as determined by chemical cross-linking. Urea dissociation kinetics of purified HpUreI were determined by means of the scintillation proximity assay (SPA), whereas urea efflux was measured in HpUreI-containing proteoliposomes using stopped-flow spectrometry to determine the kinetics and selectivity of the urea channel. The kinetic analyses revealed that urea conduction in HpUreI is pH sensitive and saturable with a half-saturation concentration (or K0.5) of ~163 mM. Binding of urea by HpUreI was increased at lower pH; however, the apparent affinity of urea binding (~150 mM) was not significantly pH dependent. The solute selectivity analysis indicated that HpUreI is highly selective for urea and hydroxyurea. Removing either amino group of urea molecules diminishes their permeability through HpUreI. Similar to urea conduction, water diffusion through HpUreI is pH-dependent with low water permeability at neutral pH.

Keywords: urea channel, proteoliposomes, HpUreI, solute permeability, urea transport

Urea is an important biological molecule with diverse functions. While urea is a nitrogen source for bacteria, mammals excrete it as a less toxic byproduct of nitrogen metabolism (1). In fish gills and mammalian kidneys urea also functions as an osmolyte (2). In Helicobacter pylori, a pathogenic bacterium responsible for several gastroduodenal disorders, including chronic active gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer, urea plays a unique and essential role for its colonization of the acidic stomach (3–6). Whereas H. pylori is a neutralophilic bacterium which grows optimally at pH 7.0, in the presence of urea it can grow below pH 4.0 (7).

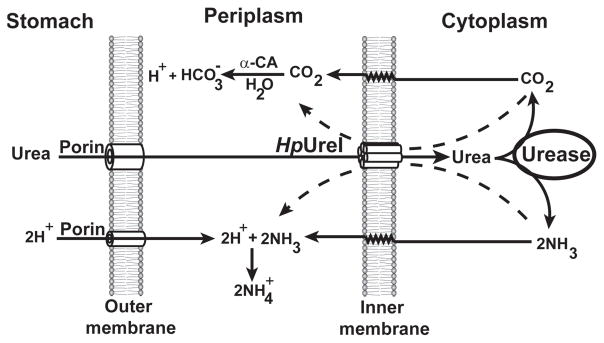

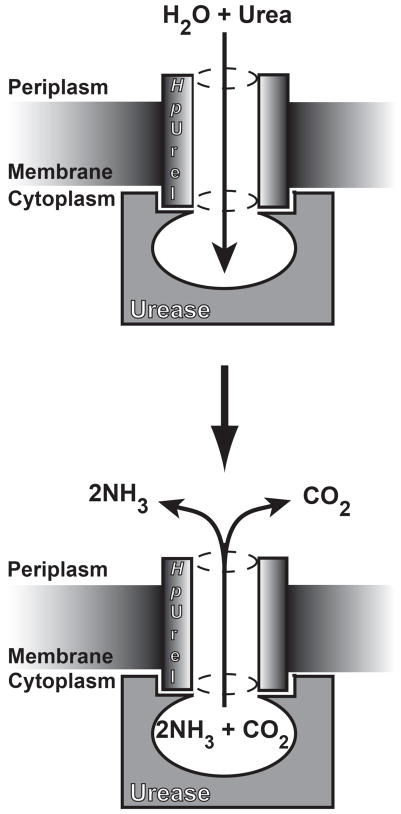

H. pylori uses a unique mechanism to take advantage of urea for neutralizing the acidic stomach (8, 9). Urea is taken up from the stomach environment via an inner membrane urea channel (HpUreI). A cytoplasmic urease then hydrolyzes imported urea into NH3 and CO2, which subsequently diffuse into the periplasmic space. There, NH3 neutralizes the acid, and CO2 is converted into HCO3− by the activity of a membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase, providing buffering in the range of pH 6.1 (Fig. 1) (9). This mechanism allows H. pylori to maintain a proton-motive force necessary for cell growth in the gastric environment (2). The urea concentration in gastric juice, like that in blood, is 3–5 mM, which is enough to support bacterial survival (2, 10, 11). HpUreI is essential for H. pylori to neutralize the acid and survive in the stomach (8, 10, 12, 13).

Figure 1.

HpUreI expression in Xenopus oocytes has demonstrated that the protein is a passive, pH-gated, and temperature-independent urea channel (8, 14). The acid sensitivity of the urea channel is essential for cytoplasmic pH homeostasis in H. pylori. When the pH is acidic (<5.0) the bacterium requires urea to produce NH3 and CO2, and the channel remains open to facilitate urea uptake. On the other hand, at neutral pH urease activity is not required, and the channel is closed to prevent toxicity due to cytoplasmic alkalization. With a molecular mass of 21.7 kDa (195 amino acids), HpUreI is one of the smallest pH-gated channels known.

There are multiple urea transport systems facilitating urea permeation across cell membranes including, but not limited to, urea transporters (UT) (15, 16) and acid-sensitive urea channels (UreI) (8). UT and HpUreI are very different in matter of sequence and topology. Unlike HpUreI, which has 6 transmembrane domains, UT consists of 12 transmembrane domains (17). Recent functional and structural studies of UT family members have indicated that they follow a channel-like mechanism (17–20). Compared to UT, our knowledge of the structure and mechanism of HpUreI channels is very limited.

In this research, we heterologously expressed and purified HpUreI. The purified HpUreI was reconstituted into liposomes and a stopped-flow assay was used to determine the kinetics of solute conduction by HpUreI. Our results indicate that the channel is selective for urea and hydroxyurea. HpUreI also conducts water in a pH-dependent manner, indicating that water and urea share a common conduction pathway. Although the urea conduction is pH sensitive, the binding of urea by HpUreI is pH independent. Finally, we propose a model which takes into account this and previous research.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of HpUreI

The genomic DNA of Helicobacter pylori strain 26695 (purchased from American Type Culture Collection, ATCC) was used as the template for the PCR amplification of the ureI gene. The amplified fragment was digested with suitable restriction enzymes and ligated into pET29b vector, which had been digested with the same restriction enzymes. In order to remove His tag during protein purification, a TEV cleavage site (ENLYFQG) was engineered between the ureI gene and a His tag.

The expression vector was transformed into E. coli BL21 Rosetta 2 (DE3) competent cells. Protein expression under various growth conditions was evaluated by detection of the His tag using HisProbe-HRP (Pierce/ThermoScientific). Optimum expression was achieved by inducing cell cultures with 0.1 mM IPTG at an OD600 of 0.6 and growing the cells overnight at 25 °C.

Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA and 4 mM βME (β-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with fresh PMSF and DNase I. Cells were lysed by two passes through an EmulsiFlex-C3 homogenizer (Avestin) and the membrane fraction was harvested by centrifugation at 138000 xg for 1 hour. The protein was extracted from the membrane by overnight agitation in extraction buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 40 mM decyl-β-D-maltoside (DM, Anatrace), 20 mM imidazole, and 4 mM βME) at 4 °C. The solubilized protein was loaded onto a Ni2+ affinity column (Ni-NTA resin, Qiagen), which was pre-equilibrated with nickel column buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 4 mM DM, 20 mM imidazole and 4 mM βME). The resin was washed first with 20 mM and then 50 mM imidazole in nickel column buffer. The protein was eluted with 400 mM imidazole in nickel column buffer. Imidazole was removed using Econo-Pac 10DG desalting columns (Bio-Rad) and the His tag was removed by overnight incubation with TEV protease at 4 °C. TEV protease and residual undigested proteins were removed by passing over a Ni2+ affinity column and collecting the flow through. The protein was injected onto a Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE healthcare) with a mobile phase of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 4mM DM and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The symmetric peak of HpUreI was collected and its purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. The size-homogeneity of the purified protein was routinely confirmed by re-injection into the size-exclusion chromatography column. All chemicals and buffers were purchased from Sigma.

Cross-linking experiments

Glutaraldehyde was used to cross-link HpUreI monomers. For the cross-linking reaction, HpUreI was purified in phosphate buffer (20 mM KPi pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 4 mM DM). To initiate the cross-linking reaction glutaraldehyde was added to the final concentration of 100mM. To monitor the progress of the reaction, aliquots (25μl) were removed from the reaction mixture at various time points of 1, 2.5, 5, 20, 60, 120 min, and the reaction was quenched by the addition of 1M Tris, pH 7.5 (final concentration of 142mM). The samples were analyzed on a 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE by silver staining.

Proteoliposomes reconstitutions

E. coli polar lipids (purchased as a chloroform solution from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) were dried under N2, washed twice with pentane, and further dried by speedvac for 1 hour. The dried lipid was resuspended in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT to 10 mg/ml. The lipid suspension was sonicated to clarity, and diluted with a DM buffer (~ 7 mM DM, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT) to 2.5 mg/ml lipid and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Protein was added to a final lipid to protein weight ratio of 100 (Xmg protein to Xmg lipid), and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Detergent was removed by incubation with Bio-beads SM-2 (Bio-Rad). The vesicles were extruded (through a 0.4 μm filter) multiple times for homogeneity. The vesicles were harvested by centrifugation at 80000xg for 1 hour at 4 °C. Monodispersity and size distributions of the vesicles were routinely verified by dynamic light scattering and the vesicle diameter was generally 100 ± 10 nm. Identical procedures were followed to prepare control liposomes in the absence of protein. All samples were assayed within a day of preparation.

To measure solute permeability coefficients at pH 5.0, the buffer in all solutions used to prepare proteoliposomes was replaced with 20 mM Na Acetate pH 5.0. To determine the pH profile of HpUreI, the vesicles were prepared at the pH range of 4.0 to 7.5 using a 20 mM citrate-phosphate buffer adjusted to the various pH values.

Solutes permeability measurements

Permeabilities for urea or urea analogues were measured using a stopped-flow spectrometer (Applied PhotoPhysics SX20) with a dead-time of ≤1 ms. To determine the solute selectivity of HpUreI the permeability assays were carried out at pH 5.0, where the channel is conductive. Each solute was loaded into the vesicles (control liposomes or HpUreI proteoliposomes) by overnight incubation in assay buffer (20mM Na Acetate pH 5.0 and 100 mM NaCl) supplemented with 200 mM urea or urea analogues. The vesicle suspension was abruptly mixed (1:1) with an assay solution supplemented with sucrose (the nonpermeant osmolyte) to make an isoosmotic solution. The osmolality of each buffer was determined using a Vapro vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor, Inc.). Upon mixing, the external concentration of the permeant solute is reduced by half generating a solute concentration gradient which drives solute efflux. Solute efflux is followed by water efflux leading to the reduction of the vesicle volume which causes an increase in the intensity of scattered light measured at λ = 440nm (21, 22). All the permeability assays were conducted at 10 °C. The rate constant of solute diffusion was determined by exponential curve fitting of the average of 5–8 traces. The measured rate constants were used to determine permeability coefficients based on Mathai and Zeidel equations (23). Each data point is the average of 3–5 independent permeability measurements.

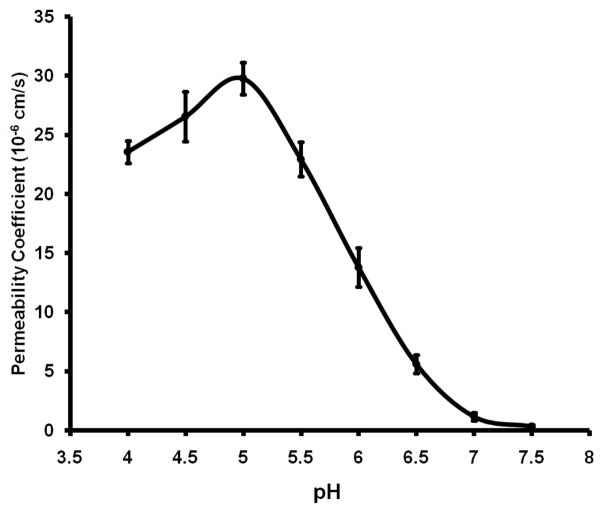

pH-activity profile of HpUreI

The pH profile of HpUreI activity was determined from 4 to 7.5. For each pH value, the proteoliposomes were independently prepared using 20 mM citrate-phosphate buffer adjusted to the desired pH. The standard deviation of each data point is a result of 3–5 experiments. Urea permeability of control liposome was also measured at each pH, to determine the background permeabilities.

Measurement of apparent K0.5 of HpUreI

To measure the kinetics parameters for urea conduction by HpUreI, the urea flux was measured at various concentration gradients of urea. To that end, HpUreI proteoliposomes were loaded with various concentrations of urea, ranging from 50 mM to 800 mM, by overnight incubation in assay buffer (20 mM citrate-phosphate pH 5.0, 100 mM NaCl) containing various concentrations of urea. The vesicles suspension was rapidly mixed (1:1) with assay solution containing isoosmotic concentrations of sucrose. The efflux of urea was measured as an increase in the intensity of scattered light at 440 nm.

Water permeability measurements

The water permeability of HpUreI was measured by rapidly mixing the proteoliposome (or liposome for control experiments) suspension in assay buffer with a hyperosmotic solution of 500 mM sucrose at 10 °C. The sucrose osmotic gradient drives water efflux and vesicle shrinkage was measured as an increase in the intensity of scattered light at λ = 440 nm. Typically 5–8 traces were averaged and used for exponential curve fitting to measure the rate constant of osmotic water efflux. All the data points represent the average of 3–5 permeability measurements from independent proteoliposome preparations. Osmotic water permeabilities were calculated from the measured rate constants using Mathai and Zeidel approaches (23).

HpUreI scintillation proximity binding assay

Binding of 181 μM 14C-urea (55 mCi/mmol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc.) to recombinant HpUreI was assayed by means of the scintillation proximity assay (SPA) (17, 24, 25). Cu2+-coated YSi SPA beads (Perkin Elmer # RPNQ00096) were diluted to 2.5 mg/mL in 150 mM Tris/Mes, pH 7.5 or pH 5.0/50 mM NaCl/20% glycerol/1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP, Sigma Co)/0.1% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside. His-tagged recombinant protein (at 250 ng per assay) and 14C-urea were added simultaneously to the YSi-SPA bead mix in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of non-labelled urea to individual wells of clear-bottom/white-wall 96-well plates (Greiner #655095). Plates were incubated in the dark at 4 °C with vigorous shaking on a vibrating platform for 15 minutes before they were counted in the SPA mode of a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta™ plate PMT counter. Non-specific background binding activity was assayed in the presence of 800 mM imidazole (as imidazole competes with the His tagged proteins) in control samples for all conditions tested and subtracted from the total binding activity (detected as counts per minute or cpm) to obtain the UreI-specific binding activity. Data points represent the mean ± standard error of triplicate determinations. Data fits of kinetic analyses were performed using non-linear regression algorithms in Prism and errors represent the S.E.M. of the fit.

Results and Discussion

Cloning, expression and purification of HpUreI

Several constructs of the ureI gene in different pET vectors, including pET29b, pET28b and pET27b, were built and screened in order to identify the best conditions for over-expression of HpUreI. In addition, several growth and expression variables were screened to determine the best conditions of HpUreI overexpression. The yield was estimated to be ~0.5 mg protein per Liter of media.

Screening of detergent solubilization showed that dodecyl maltoside (DDM), undecyl maltoside (UDM), decyl maltoside (DM) and lauryldimethylamine oxide (LDAO) all efficiently extract HpUreI, and the purification of the HpUreI in each of these detergents yielded a stable protein. We used DM for purification and all the functional studies.

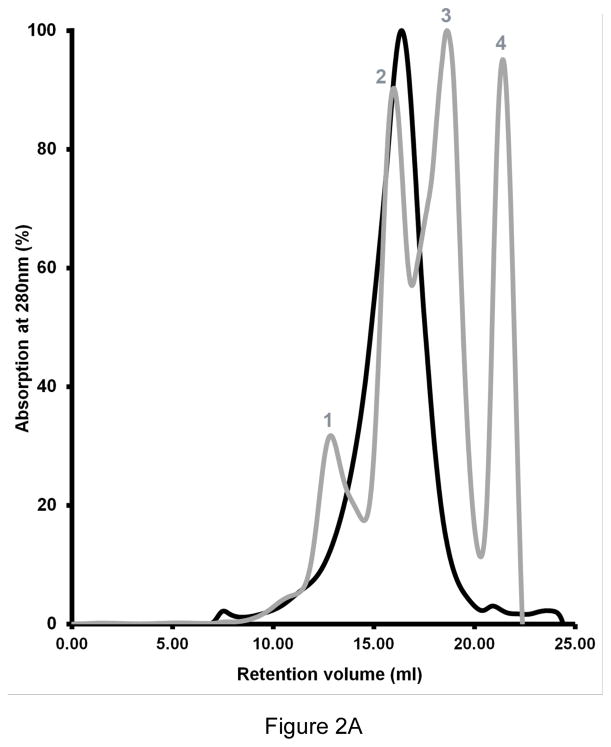

The DM extracted HpUreI was purified using Ni2+ affinity purification, followed by TEV protease digestion to remove the His tag. Undigested protein, along with TEV protease (which also carries a C-terminal His-tag) were removed by a second Ni2+ affinity column. The TEV digested HpUreI was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2A). HpUreI eluted from Superose 6 10/300 GL column as a single peak with a retention volume of 16.3 ml corresponding to a molecular mass of less than 150 kDa. SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed the purity of the protein (Fig 2B, lane 1).

Figure 2.

Oligomeric state of detergent-solubilized HpUreI

To determine the oligomeric state of detergent-solubilized HpUreI we performed cross-linking analysis. To this end, the protein was treated with glutaraldehyde for various time periods, and the products of the reaction were analyzed by 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2B, lanes 2–7). As the reaction progressed the ~20 kDa band (representing the monomer form of HpUreI) disappeared and two bands emerged migrating at ~40 kDa and ~60 kDa which represent the dimer and trimer forms of the protein, respectively. Bands larger than trimer were not observed even after 24 hours exposure to the cross-linker. The glutaraldehyde cross-linking analysis indicates that detergent-solubilized HpUreI exists as homo-trimer.

Most of the membrane channels for neutral solutes form multimeric assemblies in the biological membranes, even though each monomer can be an independent functional unit. Examples include water channels (22, 26) and ammonia channels (27). The urea transporter from the bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris also exists as homotrimer in the crystal structure (17). The trimeric assembly could be the active form of HpUreI in cell membrane.

The results of both co-immunoprecipitation analysis (28) and immunoelectron microscopy experiments (29) showed that cytoplasmic urease interacts with HpUreI. The functional unit of H. pylori urease includes two different subunits (α and β) (30). The active urease from H. pylori consist of three (αβ) heterodimers forming a trimeric assembly (αβ)3, although the crystal packing of H. pylori urease shows a dodecameric assembly of [(αβ)3]4 (31). Based on our results, one can conclude that HpUreI associates with urease through trimer-trimer interactions. This can be similar to the interaction of trimeric AmtB (an ammonia channel) with trimeric GlnK (a soluble protein which regulates AmtB activities) (32, 33).

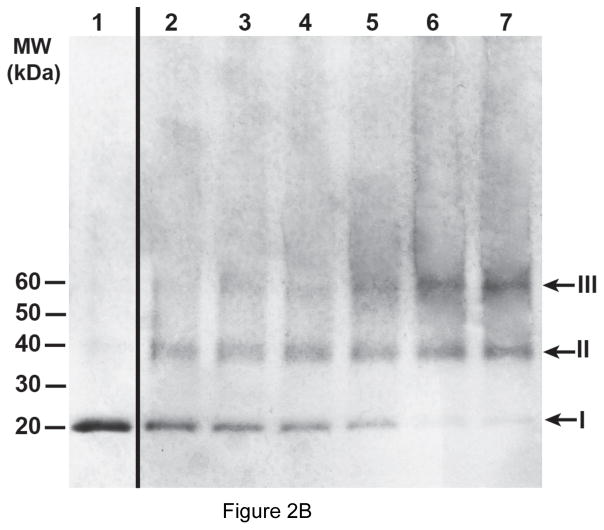

Urea permeability determination using a stopped-flow assay

A stopped-flow-based proteoliposome assay was used to measure urea permeability. HpUreI-containing proteoliposomes or control liposomes were loaded with urea by incubation in solute containing buffer. In a stopped-flow spectrometer, the vesicle suspension was abruptly mixed with an equal volume of an isoosmotic solution of buffered sucrose. This results in the efflux of urea along its concentration gradient, which consequently initiates water efflux causing shrinkage of the vesicles. We determined the rate of vesicle shrinkage, measured by the change in intensity of the scattered light at λ=440nm, as a function of the rate of urea efflux (Fig. 3). Loading vesicles with self-quenching concentrations of carboxyfluorescein is another common method to monitor the volume changes. (27, 34) However, carboxyfluorescein (CF) is a pH-sensitive dye whose fluorescence is much reduced below pH 7.0, restricting its usage under acidic conditions. Furthermore, these two methods yielded identical urea permeability measurements at neutral pH (data not shown). Therefore, we chose to use light scattering measurements.

Figure 3.

Our assays show that the urea permeability coefficients of liposomes without protein at pH 7.5 and 5.0 are similar (0.032 (±0.007) ×10−6 cm/s and 0.033 (±0.008) ×10−6 cm/s, respectively) (Fig. 3; green and red traces). The urea permeability coefficient of HpUreI proteoliposomes at pH 7.5 is 0.058 (±0.013) × 10−6 cm/s, which is very close to that of control liposomes at either pH (Fig. 3; blue trace). However, HpUreI proteoliposomes at pH 5.0 have a urea permeability coefficient of 21.0 (±0.83) × 10−6 cm/s (Fig. 3; black trace), indicating significant increase (>600-fold) with respect to the control liposome permeability.

pH-activity profile of HpUreI

Using the oocyte expression system, HpUreI was shown to be a pH sensitive channel with highest activity at acidic pH (8, 35). Our stopped-flow assays also show that HpUreI displays a significant increase in urea conduction (more than 350-fold) when the pH decreases from 7.5 to 5.0 (0.058 (±0.013) × 10−6 cm/s vs. 21.0 (±0.83) × 10−6 cm/s) (Fig. 4). Previous results have shown that urea uptake in HpUreI-expressing Xenopus oocytes at pH 5.0 was only 6- to10-fold higher than that in either injected oocytes at pH 7.5 or non-injected oocytes at either pH (8). The lower activities observed in Xenopus oocyte expression may be due to the instability of prokaryotic HpUreI in this eukaryotic expression system. However, previous in vivo assays (using oocytes) (35) and our in vitro pH profile assay show that decreasing pH activates urea conduction by HpUreI and that the pH of the half-maximal activation is ~5.9 (pH0.5=5.9, corresponding to a H+ concentration of 1.26 μM) (Fig. 4). The periplasmic domains are suggested to be involved in the pH gating of HpUreI (14). The pH0.5 of 5.9 is similar to the pKa of the histidine residue (6.0), suggesting these residues in the periplasmic domains may be involved in the pH gating mechanism of HpUreI.

Figure 4.

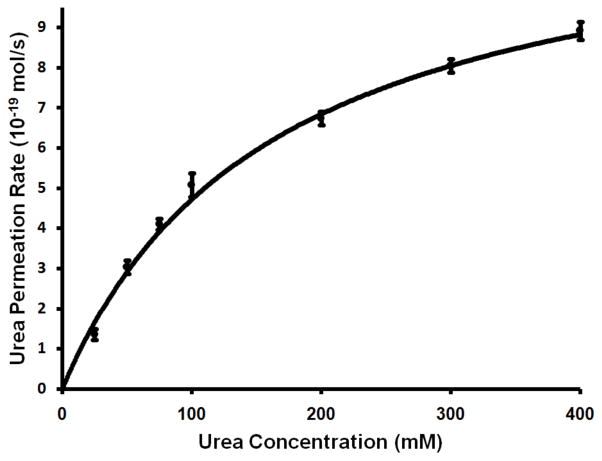

Kinetics measurements of urea conduction by HpUreI

The stopped-flow proteoliposome assay was used to determine the kinetics of urea conduction by HpUreI. Proteoliposomes containing HpUreI were loaded with various urea concentrations and the efflux of urea was measured at pH 5.0 under isoosmotic conditions (Fig. 5). The data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation and the half-saturation concentration for urea permeation by HpUreI (apparent K0.5) was determined to be 163±20 mM. This apparent K0.5 for urea conduction in HpUreI is very close to previously reported values for UTs (218 mM for mammalian erythrocyte UT-B (18), 182 mM (19) or 104 ± 9.96 mM (20) for bacterial ApUT). It seems, despite their differences in the sequence and topology, UT and UreI families may share similar mechanism of solute conduction. Consistent with our results, Weeks et al. showed that a concentration gradient up to 100mM does not saturate the solute conduction (8). We observed that the saturation of the solute conduction occurs only when urea concentration gradient is above 400–500 mM.

Figure 5.

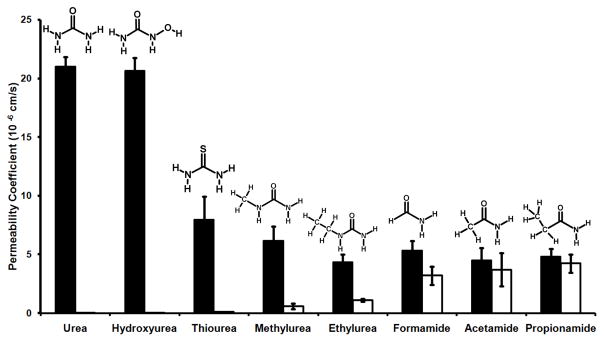

Solute selectivity of the channel

Solute selectivity is one of the most distinguishing features of a channel protein. Aside from urea, which molecules can pass through urea channels has not been thoroughly investigated. Stopped-flow light-scattering measurements were used to investigate the conduction of various urea analogues through HpUreI. The permeability coefficient for each solute was determined for a quantitative comparative analysis. All the permeability assays were performed at pH 5.0 where the channel is conductive. Urea analogues were loaded into liposomes in a similar manner as urea.

Our results show that urea and hydroxyurea have the highest permeability coefficients among the solutes examined (Fig. 6). This indicates that attachment of a hydroxyl group on the amino groups does not have any effect on solute conduction in HpUreI.

Figure 6.

Thiourea (the =O of urea was replaced by =S) diffuses through HpUreI with a ~62% decrease in permeability coefficient (21 (±1.7) ×10−6 cm/s for urea vs. 7.95 (±1.97) ×10−6 cm/s for thiourea) (Fig. 6). Contradictory to a previous report suggesting that HpUreI does not conduct thiourea (8), our results indicate that HpUreI does increase thiourea permeability with respect to the control liposome.

The significance of the two amino groups of the urea molecule was determined by replacing one of the amino groups with –H (formamide), -CH3 (acetamide) or –CH2CH3 (propionamide). These solutes diffuse through lipid bilayer, and consequently display permeability through control liposomes. Our results show that the permeability of these three solutes through HpUreI proteoliposomes is not significantly higher than that of control liposomes (Fig. 6). Therefore, removing one of the amino groups almost abolishes the ligand’s permeability. This indicates the presence of both amino groups is necessary for ligand recognition and conduction by HpUreI.

To determine the steric exclusion properties of the urea channel, the permeability of ligands with methyl or ethyl substituents on the amino groups was evaluated. The proteoliposome assays show that the permeability of methyl- and ethylurea are 4-fold less than that of urea (Fig. 6). Overall, our results indicate that the urea channel is highly selective for urea and hydroxyurea. Moreover, the solute selectivity of HpUreI resembles that of UT. These results imply similarity in the solute pathways of UTs and HpUreI channels.

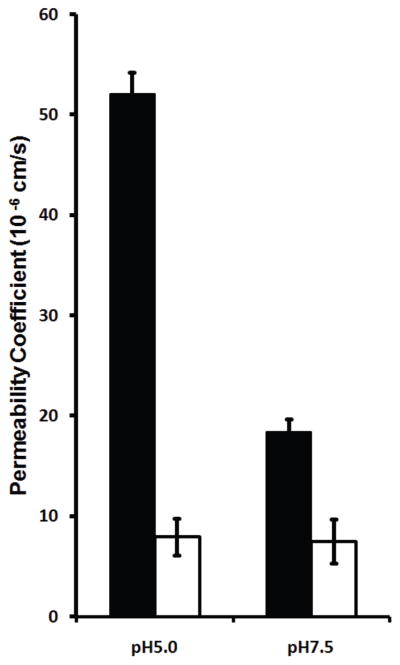

Water permeability through HpUreI proteoliposomes were measured by monitoring changes in vesicles volume due to external osmotic pressure at two pH values. For this assay the empty vesicles were abruptly mixed with a solution of 500 mM sucrose and changes in volume were monitored based on light scattering. At pH 5.0, the osmotic water permeability coefficient of HpUreI proteoliposomes displayed a 6.6 fold increase compared to control vesicles (52.1 (±2.1) ×10−6 cm/s vs. 8.0 (±1.9) ×10−6 cm/s), indicating that water diffuses through the channel (Fig. 7). The osmotic water permeability coefficient of HpUreI at pH 7.5 was ~2.5-fold higher than that of control liposomes (18.4 (±1.3) ×10−6 cm/s vs. 7.5 (±2.2) ×10−6 cm/s). At pH 7.5, where the channel is impermeable to urea, water permeability decreases significantly (52.1 (±2.1) ×10−6 cm/s at pH 5.0 vs. 18.4 (±1.3) ×10−6 cm/s at pH 7.5). These results show that water permeability in HpUreI is pH-sensitive and suggests that water and urea share a common conduction pathway.

Figure 7.

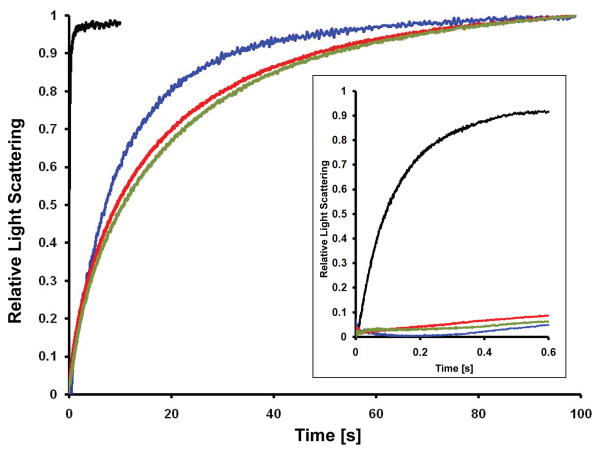

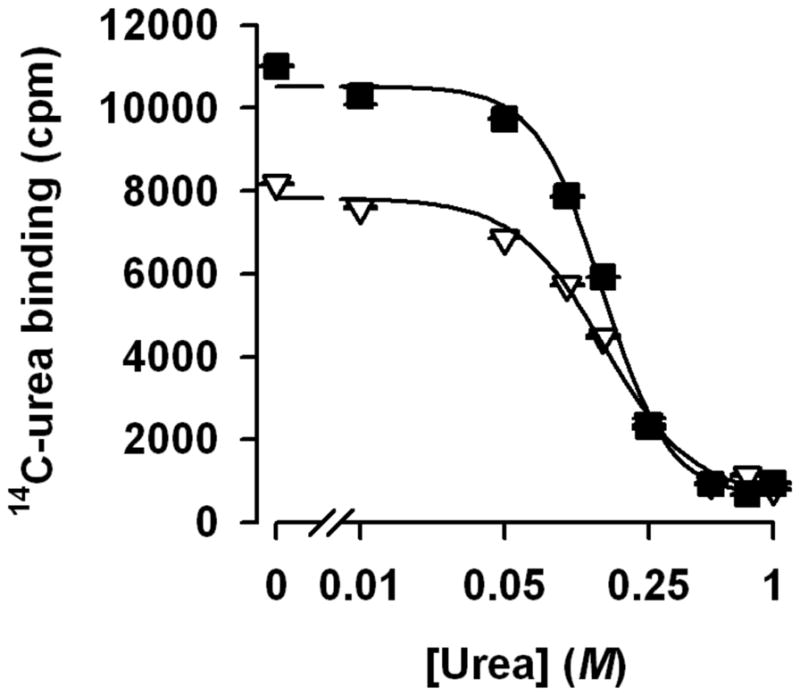

The binding affinity of urea to HpUreI

Binding kinetics of HpUreI for urea was measured at pH 5.0 and 7.5 in order to determine how the changes in pH affect urea binding to the channel. The copper chelate affinity-based scintillation proximity assay (SPA), was used to directly measure the binding of C14-urea to the detergent-solubilized HpUreI channel. The SPA assay has been used previously to measure the affinity of various ligands to their cognate transporters and channels, even when the affinity is relatively low (17, 24). Competition of binding of 181 μM C14-urea with non-labeled urea revealed half-maximum inhibition constants (IC50) of 153 ± 34 mM and 149 ± 23 mM at pH 5.0 and pH 7.5, respectively (Fig. 8). This apparent affinity for urea binding is consistent with the apparent K0.5 value for urea conduction determined using the proteoliposome assay (K0.5 = 163±20 mM). Notably, however, whereas the apparent urea affinity is independent of the pH, binding of 181 μM C14-urea at pH 5.0 was about 35 % higher than that observed at pH 7.5. In addition, fitting the data to the Hill equation revealed a Hill coefficient (a measure for the cooperativity of ligand binding by enzymes) of 2.7 ± 0.37 at pH 5.0, whereas the Hill coefficient at pH 7.5 was found to be 2 ± 0.32.

Figure 8.

There are significant differences in the Kd values between the bacterial UT (17–20) and HpUreI (2.3 ± 0.14 mM for UT vs. ~150 mM for HpUreI), indicating that UT has one or more high affinity sites for urea. On the other hand, obtaining Hill coefficients larger than 1 may indicate that HpUreI, like UT (17–20), has more than one urea binding site(s). In fact, it is tempting to speculate whether the Hill coefficients of 2 and 2.7 (at pH 7.5 and 5.0, respectively, Fig. 8) could be indicative of a different number of urea binding sites in HpUreI. Note that the 35 % increase in the binding of 14C-urea at pH 5.0 corresponds to the higher Hill coefficient. Further functional and structural studies of HpUreI will shed light on how these channels conduct solutes and determine the similarities and differences between UTs and HpUreI transport mechanisms.

The mechanism for acid acclimation by H. pylori

Both HpUreI and urease are essential for H. pylori to resist the acidic environment of the stomach. At acidic pH values HpUreI undergoes a conformation change which allows for urea conduction and conducts urea from the periplasm into the cytoplasm There cytoplasmic ureases convert urea into NH3 and CO2, which return into the periplasm to neutralize the acid (8). It has been shown that HpUreI associates with urease in a pH dependent manner, and that the products of urease activity (NH3 and CO2) are able to diffuse through HpUreI (36).

The accumulation of high levels of NH3 inside the cell causes alkalization of the cytoplasm and can be toxic for bacterium. Therefore, the cytoplasm should be protected from the products of urea hydrolysis. It has been suggested that the association of urease and HpUreI prevents the dissipation of the products of urease activity into the cytoplasm (28, 29, 36). The urease-HpUreI trimer-trimer complex should seal the active site of urease in order to prevent the escape of the products into the cytoplasm. The active site should also be impervious to water; otherwise the generated NH3 would change the cytoplasmic pH by interacting with bulk water and becoming NH4+. Since water molecules can diffuse through HpUreI (based on our results), the water molecules necessary for the enzymatic reaction most likely diffuse from the periplasm to the active site through HpUreI. Based on our results and previous studies we propose the following mechanism for acid acclimation by H. pylori (Fig. 9). Under acidic conditions, HpUreI conducts urea and water into the active site of urease where they are converted into NH3 and CO2. The products are then transferred to the periplasm (their final destination) by HpUreI. In this mechanism the cytoplasm is completely protected from the substrate and products. Further studies are necessary to determine the mechanism of action for HpUreI-urease complex.

Figure 9.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank University of Iowa, Carver College of Medicine for funding.

Footnotes

The authors thank University of Iowa, Carver College of Medicine for funding.

References

- 1.Sands JM. Mammalian urea transporters. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:543–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sachs G, Kraut JA, Wen Y, Feng J, Scott DR. Urea transport in bacteria: acid acclimation by gastric Helicobacter spp. J Membr Biol. 2006;212:71–82. doi: 10.1007/s00232-006-0867-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:449–490. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makola D, Peura DA, Crowe SE. Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastrointestinal diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:548–558. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318030e3c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerrits MM, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. Helicobacter pylori and antimicrobial resistance: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:699–709. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Megraud F. Basis for the management of drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori infection. Drugs. 2004;64:1893–1904. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464170-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan DR, Freedman R, Depew CE, Kraft WG. Growth of Campylobacter pylori in liquid media. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2123–2125. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2123-2125.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weeks DL, Eskandari S, Scott DR, Sachs G. A H+-gated urea channel: the link between Helicobacter pylori urease and gastric colonization. Science. 2000;287:482–485. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs G, Weeks DL, Wen Y, Marcus EA, Scott DR, Melchers K. Acid acclimation by Helicobacter pylori. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:429–438. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skouloubris S, Thiberge JM, Labigne A, De Reuse H. The Helicobacter pylori UreI protein is not involved in urease activity but is essential for bacterial survival in vivo. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4517–4521. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4517-4521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mollenhauer-Rektorschek M, Hanauer G, Sachs G, Melchers K. Expression of UreI is required for intragastric transit and colonization of gerbil gastric mucosa by Helicobacter pylori. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:659–666. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, Ketchum KA, Klenk HP, Gill S, Dougherty BA, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness EF, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak HG, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald LM, Lee N, Adams MD, Hickey EK, Berg DE, Gocayne JD, Utterback TR, Peterson JD, Kelley JM, Cotton MD, Weidman JM, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes WS, Borodovsky M, Karp PD, Smith HO, Fraser CM, Venter JC. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi L, Hou X, Yi S, Zhang J. Effect of the vacuolation of Helicobacter pylori. J Tongji Med Univ. 2001;21:97–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02888065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weeks DL, Sachs G. Sites of pH regulation of the urea channel of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1249–1259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.You G, Smith CP, Kanai Y, Lee WS, Stelzner M, Hediger MA. Cloning and characterization of the vasopressin-regulated urea transporter. Nature. 1993;365:844–847. doi: 10.1038/365844a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagnasco SM. Role and regulation of urea transporters. Pflugers Arch. 2005;450:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin EJ, Quick M, Zhou M. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of the kidney urea transporter. Nature. 2009;462:757–761. doi: 10.1038/nature08558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayrand RR, Levitt DG. Urea and ethylene glycol-facilitated transport systems in the human red cell membrane. Saturation, competition, and asymmetry. J Gen Physiol. 1983;81:221–237. doi: 10.1085/jgp.81.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godara G, Smith C, Bosse J, Zeidel M, Mathai J. Functional characterization of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae urea transport protein, ApUT. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1268–1273. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90726.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raunser S, Mathai JC, Abeyrathne PD, Rice AJ, Zeidel ML, Walz T. Oligomeric structure and functional characterization of the urea transporter from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Illsley NP, Verkman AS. Serial permeability barriers to water transport in human placental vesicles. J Membr Biol. 1986;94:267–278. doi: 10.1007/BF01869722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu D, Libson A, Miercke LJ, Weitzman C, Nollert P, Krucinski J, Stroud RM. Structure of a glycerol-conducting channel and the basis for its selectivity. Science. 2000;290:481–486. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathai JC, Zeidel ML. Measurement of water and solute permeability by stopped-flow fluorimetry. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;400:323–332. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-519-0_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quick M, Javitch JA. Monitoring the function of membrane transport proteins in detergent-solubilized form. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:3603–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609573104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi L, Quick M, Zhao Y, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. The mechanism of a neurotransmitter:sodium symporter--inward release of Na+ and substrate is triggered by substrate in a second binding site. Mol Cell. 2008;30:667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith BL, Agre P. Erythrocyte Mr 28,000 transmembrane protein exists as a multisubunit oligomer similar to channel proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:6407–6415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khademi S, O’Connell J, 3rd, Remis J, Robles-Colmenares Y, Miercke LJ, Stroud RM. Mechanism of ammonia transport by Amt/MEP/Rh: structure of AmtB at 1.35 A. Science. 2004;305:1587–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.1101952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voland P, Weeks DL, Marcus EA, Prinz C, Sachs G, Scott D. Interactions among the seven Helicobacter pylori proteins encoded by the urease gene cluster. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G96–G106. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00160.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong W, Sano K, Morimatsu S, Scott DR, Weeks DL, Sachs G, Goto T, Mohan S, Harada F, Nakajima N, Nakano T. Medium pH-dependent redistribution of the urease of Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:211–216. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu LT, Mobley HL. Purification and N-terminal analysis of urease from Helicobacter pylori. Infection and immunity. 1990;58:992–998. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.992-998.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ha NC, Oh ST, Sung JY, Cha KA, Lee MH, Oh BH. Supramolecular assembly and acid resistance of Helicobacter pylori urease. Nature structural biology. 2001;8:505–509. doi: 10.1038/88563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruswitz F, O’Connell J, 3rd, Stroud RM. Inhibitory complex of the transmembrane ammonia channel, AmtB, and the cytosolic regulatory protein, GlnK, at 1.96 A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:42–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609796104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conroy MJ, Durand A, Lupo D, Li XD, Bullough PA, Winkler FK, Merrick M. The crystal structure of the Escherichia coli AmtB-GlnK complex reveals how GlnK regulates the ammonia channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:1213–1218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610348104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeidel JD, Mathai JC, Campbell JD, Ruiz WG, Apodaca GL, Riordan J, Zeidel ML. Selective permeability barrier to urea in shark rectal gland. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F83–89. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00456.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weeks DL, Gushansky G, Scott DR, Sachs G. Mechanism of proton gating of a urea channel. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9944–9950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Wen Y, Singh S, Feng J, Sachs G. Cytoplasmic histidine kinase (HP0244)-regulated assembly of urease with UreI, a channel for urea and its metabolites, CO2, NH3, and NH4(+), is necessary for acid survival of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:94–103. doi: 10.1128/JB.00848-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]