Abstract

Background

Little is known about patterns of medication use and lifestyle counseling in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) in the United States.

Objective

We sought to evaluate trends in both medical therapy and lifestyle counseling for PAD patients in the United States from 2005 through 2012.

Methods

Data from 1,982 outpatient visits among patients with PAD were obtained from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, a nationally representative assessment of office-based and hospital outpatient department practice. We evaluated trends in the proportion of visits with medication use (antiplatelet therapy, statins, ACE-inhibitors [ACE-I] or angiotensin receptor blockers [ARB], and cilostazol) and lifestyle counseling (exercise or diet counseling and smoking cessation).

Results

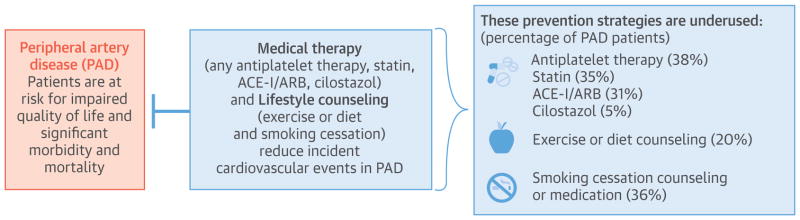

Over the 8-year period, the average annual number of ambulatory visits in the U.S. for PAD was 3,883,665. Across all visits, mean age was 69.2 years, 51.8% were female and 56.6% were Non-Hispanic white. Comorbid coronary artery disease (CAD) was present in 24.3% of visits. Medication use for cardiovascular prevention and symptoms of claudication was low: any antiplatelet therapy in 35.7% (standard error [SE] 2.7), statin 33.1% (SE, 2.4), ACE-I/ARB 28.4% (SE, 2.0), and cilostazol in 4.7% (SE, 1.0) of visits. Exercise or diet counseling was used in 22% (SE, 2.3) of visits. Among current smokers with PAD, smoking cessation counseling or medication was used in 35.8% (SE, 4.6) of visits. There was no significant change in medication use or lifestyle counseling over time. Compared to visits for patients with PAD alone, comorbid PAD and CAD were more likely to be prescribed antiplatelet therapy (OR 2.6 [1.8–3.9]), statins (OR 2.6 [1.8–3.9]), ACE-I/ARB (OR 2.6 [1.8–3.9]), and smoking cessation counseling (OR 4.4 [2.0–9.6]).

Conclusions

The use of guideline-recommended therapies in patients with PAD was much lower than expected, which highlights an opportunity to improve the quality of care in these high-risk patients.

Keywords: PAD, Cardiovascular Prevention, Lifestyle, Epidemiology

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a highly prevalent atherosclerotic syndrome with an estimated global population burden of ~200 million people (1). Because of the aging population and risk factor trends, the prevalence of PAD is increasing (2,3). Patients with PAD are at heightened risk for adverse cardiovascular and limb events and impaired quality of life (4). In fact, PAD is considered a coronary artery disease (CAD) risk equivalent (5). From a societal perspective, the consequences of PAD are significant (6).

Given its high prevalence and poor prognosis, and shared risk factors with CAD, a major goal of PAD treatment includes risk factor modification and prevention of cardiovascular events (7). Guideline directed therapy includes cardioprotective pharmacotherapies (i.e., antiplatelet therapy; statins; and blood pressure control, preferably with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [ACE-I] or angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs]) and lifestyle counseling for healthy behaviors (i.e., diet, physical activity, and smoking cessation) (6,8). Adherence to pharmacologic and lifestyle recommendations in PAD is uncertain. Several studies have shown that the use of proven cardioprotective medication for secondary prevention in patients with PAD significantly lags behind treatment for CAD (9–12). Previous analyses of PAD cohorts have been limited to populations enrolled in clinical trials, patients admitted to the hospital, patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization, or a single snapshot in time. Moreover, most studies of guideline adherence have focused on pharmacologic therapies. Effective non-pharmacologic therapies for PAD exist, including smoking cessation, regular physical activity and diet counseling (6,8).

There is little known about national patterns of medication use and lifestyle counseling in patients with PAD in the United States; the extent to which trends may be attributable to changing population demographics, risk factors, and provider characteristics; or whether sex or racial/ethnic disparities exist in its use. Examining differences in this context is important because differences in the use (underuse) of medical therapies and lifestyle counseling could contribute to poorer cardiovascular health outcomes observed in certain groups. To answer these questions, we used nationally representative data to explore trends in medication use and lifestyle counseling in the United States among patients with PAD; investigate whether these trends may be attributable to shifts in population demographics, clinical risk factors, and provider characteristics; and evaluate whether sex or racial/ethnic disparities exist in such patients.

Methods

Data and Study Population

We analyzed data from the 2006–2013 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), nationally representative surveys of adults seeking ambulatory care.(13) We included all visits to office-based physicians and hospital-based outpatient clinics by adults (18 years of age or older; N = 418,889 adult visits). The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conduct the NAMCS and NHAMCS annually on a nationally representative sample of visits to office-based physicians, hospital-based outpatient clinics, and emergency departments in the United States. For the NAMCS, each physician is randomly assigned to a 1-week reporting period during which a random sample of visits are surveyed systematically. Data are collected on patients’ symptoms, comorbidity, and demographic characteristics; physicians’ diagnoses; medications ordered or provided; and medical services provided. For the NHAMCS, a systematic random sample of patient visits in selected non-institutional general and short-stay hospitals are surveyed during a randomly assigned 4-week reporting period. The data collected on patient and provider characteristics are comparable to those collected in the NAMCS. Data on outpatient hospital departments and community health centers from the NHAMCS were unavailable in 2012–2013, but the majority of ambulatory care is performed in office-based visits and captured by the NAMCS (93% of visits during 2006–2011 occurred in the office rather than hospital outpatient departments, and 99% of office visits occurred outside of community health centers). However, we adjusted for the absence of these 2 care sites in our regression analyses and used the ratio of estimates derived from 2006–2011 with and without hospital outpatient/community health center visits to adjust 2012–2013 estimates of care provision and visit volume (14).

The NAMCS and NHAMCS intake materials allow physicians and staff to record up to three reasons for each visit and three diagnoses related to the visit, in addition to capturing several other major comorbid diagnoses (coded by NCHS staff using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]). From 2005 to 2013, the physician and hospital/outpatient clinic response rates in the NAMCS and NHAMCS ranged from 54% to 73% (except in 2012, when NAMCS response was 39%) and 80% to 95%, respectively, and item nonresponse rates were generally <5% in both surveys.

Study Population and Measures

We identified patients with PAD based on visit diagnoses using ICD-9 codes, including: 440.20–440.24, 440.29, 440.30–440.32, 440.4, 440.9, 443.81, 443.9, 445.02, and 785.4.(15) We used visit diagnoses and reasons for visit from our prior work to identify patients with other risk factors for adverse cardiovascular events, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, obesity, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CAD, and stroke (16,17). We were unable to validate our PAD diagnosis codes but they were extracted from an American Heart Association Scientific Statement, and the NAMCS/NHAMCS uses rigorous methods to review and classify data reported on Patient Record Forms.

We examined physician decision-making and treatment patterns for patients with PAD using: 1) Multum Lexicon drug codes and therapeutic drug categories and NCHS generic codes for antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, and prasugrel), cilostazol, statins, ACE-Inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEi/ARBs), and smoking cessation medications (nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, or bupropion); and 2) physicians’ reports of their provision of behavioral therapy (diet, weight loss, or exercise counseling) and smoking cessation therapy among smokers during the visit. A maximum of 8 medications could be recorded for visits between 2006 and 2011 and this increased to 10 medications in 2012–2013. We limited our accounting to the first 8 medications for each visit across all years for conformity but performed a sensitivity analysis in which up to 10 medications were assessed. This sensitivity analysis did not significantly change our results.

Other Measures

To examine factors associated with diagnostic and treatment patterns, we extracted information on demographic characteristics including age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance (private, Medicare, Medicaid, self-pay/no-charge, and other/unknown), U.S. census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and urban or rural setting. We characterized patients as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other race. In sub-analyses, physician specialty was divided into cardiologists and primary care physicians (general/family practice physicians and internists) because these physicians primarily manage PAD. Vascular surgeons were not included in these sub-analyses because they were not identified in the dataset.

Statistical Analysis

We used summary statistics to estimate the prevalence of PAD and management patterns among patients with and without concurrent CAD. We estimated simple logistic regressions with year included as a continuous linear predictor to examine time trends. We also estimated simple logistic regression models to examine differences in care among patients with PAD and CAD versus PAD alone, and among patients cared for by cardiologists versus primary care physicians. These models also adjusted for care site, based on whether visits occurred in a physician office, hospital outpatient department, or community health center. Multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for patients’ clinical risk factors and demographic characteristics, insurance status, geographical region, setting (urban or rural), and care site. Analyses accounting for specialty were limited to the NAMCS because specialty information was unavailable in NHAMCS. To determine whether specific patient and provider characteristics accounted for any overall trends we observed, we constructed simple logistic regression models that assessed whether demographic factors or physician specialty changed in prevalence over the duration of our study period. We All analyses accounted for the complex sampling design of the NAMCS and NHAMCS and were performed using Stata, version 14 (StataCorp, Inc. College Station, Texas) (18).

Results

Over the 8-year period, the average annual number of ambulatory visits in the U.S. for PAD was 3,750,000. The estimated number of annual visits for PAD in the United States increased from 2.7 million (95% CI, 1.9–3.5 million) in 2006 to 3.4 million (95% CI, 2.4–4.4 million) in 2013. The overall prevalence of a PAD diagnosis in adults in the data set was 0.4%. Of all visits among patients with PAD, the prevalence of PAD with concomitant CAD was 24.1% and did not change significantly over time (Table 1). Patient age, sex, race/ethnicity distribution, geographic region distribution, and proportion with reported Medicare coverage also did not change significantly over time in patients with PAD, but the proportion of visits by females fell over time (P<0.01). The prevalence of cardiologist visits did not change over time (22% in 2006 to 21% in 2013, P = 0.88 for trend).

Table 1.

U.S. Ambulatory Care Visits in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease, by Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, 2006–2013

| All PAD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | Unweighted Visits, n | Annual Weighted Visits, n | Percent, % | Std. Err. |

| All visits | 1,982 | 3,781,624 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Age, years | ||||

| <65 | 688 | 1,257,975 | 33.3 | 1.9 |

| 65–79 | 838 | 1,624,249 | 43.0 | 1.9 |

| ≥80 | 456 | 899,399 | 23.8 | 1.7 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 909 | 1,837,938 | 49.6 | 2.1 |

| Male | 1,073 | 1,907,686 | 50.4 | 2.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,142 | 2,124,148 | 56.2 | 2.6 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 241 | 383,805 | 10.1 | 1.8 |

| Hispanic | 152 | 290,825 | 7.7 | 1.1 |

| Other/unknown | 447 | 982,846 | 26.0 | 2.7 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 422 | 953,056 | 25.2 | 2.0 |

| Medicare | 1,289 | 2,422,815 | 64.1 | 2.2 |

| Medicaid | 129 | 161,790 | 4.3 | 0.8 |

| Other/unknown | 81 | 171,348 | 4.5 | 1.0 |

| Uninsured | 61 | 72,614 | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| US Region | ||||

| Northeast | 373 | 698,106 | 18.5 | 2.4 |

| Midwest | 494 | 703,023 | 18.6 | 2.0 |

| South | 859 | 1,847,701 | 48.9 | 3.6 |

| West | 256 | 532,793 | 14.1 | 1.8 |

| Setting | ||||

| Urban | 1,791 | 3,349,979 | 88.6 | 2.3 |

| Rural | 191 | 431,644 | 11.4 | 2.3 |

| Risk factor history | ||||

| Obesity | 178 | 401,346 | 10.6 | 1.5 |

| Smoker | 416 | 771,949 | 20.4 | 1.7 |

| COPD | 215 | 452,067 | 12.0 | 1.3 |

| Dyslipidemia | 711 | 1,507,176 | 39.9 | 2.8 |

| Diabetes | 755 | 1,209,135 | 32.0 | 2.2 |

| Hypertension | 1,270 | 2,458,404 | 65.0 | 2.2 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 162 | 296,961 | 7.9 | 1.2 |

| Comorbid cardiovascular diseases | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 425 | 912,113 | 24.1 | 1.9 |

| Stroke | 255 | 444,028 | 11.7 | 1.3 |

Abbreviations: PAD, peripheral artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAD, coronary artery disease

Note: All analyses account for the complex sampling design of the NAMCS and NHAMCS

Pharmacologic Therapy

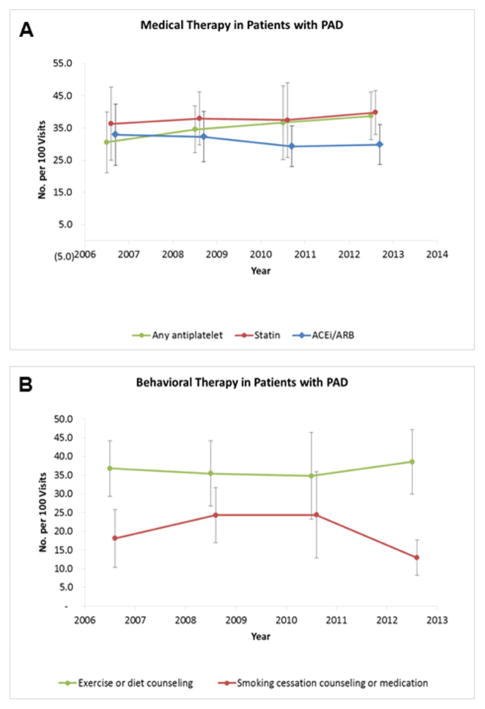

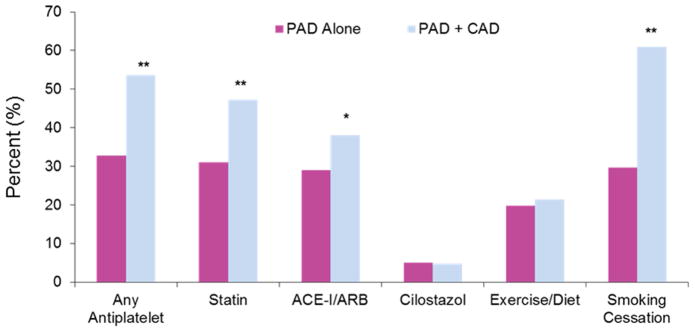

The proportion of visits with reported use of antiplatelet therapy was 36.3% in 2006–2007 and 39.7% in 2012–2013, with no significant change over time (P = 0.59 for trend; Figure 1A). Neither aspirin nor clopidogrel use changed over time. Concomitant use of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin plus clopidogrel was infrequent (7.3% in 2006–2007 to 7.1% in 2012–2013, P=0.38 for trend). Visits by patients with PAD and CAD were more likely to be on antiplatelet therapy than PAD alone (Figure 2). When stratified by coexistent CAD, visits for PAD without CAD reported a numerical increase in the use of any antiplatelet therapy (33.8% in 2006–2007 to 37.6% in 2012–2013) and aspirin (21% in 2006–2007 to 29.5% in 2012–2013) over time, though these trends were not statistically significant (P = 0.72 and P = 0.38, respectively). There was no change in antiplatelet therapy over time in patients with concomitant PAD and CAD (44.5%–46.6%, P = 0.43 for trend).

Figure 1. Time trends for reported a) medication use and b) lifestyle counseling in patients with peripheral artery disease, 2006 to 2013.

Data for medication use include any antiplatelet therapy, statins and ACE-Inhibitors or Angiotensin receptor blockers. Data for lifestyle counseling include physical activity or diet counseling and smoking cessation.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of medication use and lifestyle counseling in patients with peripheral artery disease alone versus peripheral artery disease with concomitant coronary artery disease.

The overall proportion of visits with reports of statin therapy was 35% (Table 2) and did not change significantly over time (30.5% in 2006–2007 to 38.8% in 2012–2013, P = 0.18 for trend; Figure 1A). The most substantial increase in statin use was observed in patients with PAD alone, which trended toward significance (23.6% to 35.7%, P = 0.057 for trend). The proportion of visits with reports of ACE-inhibitors or ARBs was 31.1% and did not change significantly over time (32.9% in 2006–2007 to 29.7% in 2012–2013, P = 0.51 for trend). Use of cilostazol was noted in 5% of all visits and did not change over time (P = 0.85 for trend).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Medication Use or Lifestyle Counseling in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease Seeing Physicians in U.S. Ambulatory Care Visits, 2006–2013

| All PAD, Years 2006–2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | Unweighted Visits, n | Annual Weighted Visits, n | Percent, % | Std. Err. |

| Medical Therapy | ||||

| Any antiplatelet therapy | 633 | 1,400,619 | 37.8 | 2.6 |

| Aspirin | 497 | 1,059,044 | 28.6 | 2.2 |

| Clopidogrel | 287 | 699,383 | 18.1 | 1.9 |

| Statin | 557 | 1,297,320 | 35.0 | 2.4 |

| ACE-I/ARB | 482 | 1,152,083 | 31.1 | 2.0 |

| Cilostazol | 71 | 186,216 | 5.0 | 1.0 |

| Lifestyle Counseling | ||||

| Exercise or diet counseling | 299 | 745,081 | 20.1 | 2.2 |

| Smoking Cessation | 146 | 274,752 | 36.3 | 3.9 |

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker

Note: All analyses account for the complex sampling design of the NAMCS and NHAMCS

Lifestyle Counseling

The proportion of patient visits with reported exercise or diet counseling did not change over time (18% in 2006–2007 to 12.7% in 2012–2013, P=0.23 for trend). In our visit sample, 20% of patients were current smokers, 51% of patients were past smokers, and smoking status was not reported in 29% of visits. Among smokers, smoking cessation counseling or pharmacotherapy was observed in 36.2% of visits and this did not change over time (36.8% in 2006–2007 to 38.7% in 2012–2013, P=0.96 for trend; Table 2; Figure 1B).

Predictors of Medication use and Lifestyle Counseling

We assessed predictors of medication use and lifestyle counseling using data from the 1,982 surveys among patients with a PAD diagnosis in 2006 through 2013 (Online Table 1). Potential predictors included age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, geographic region, setting, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbid cardiovascular disease, and time trend. The only significant variable associated with the use of antiplatelet therapy was concomitant CAD (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.6, 3.4). Significant variables associated with statin use were dyslipidemia (OR 3.3, 95% CI 2.2, 5.1) and concomitant CAD (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0, 2.4). Use of ACE-inhibitors/ARBs was associated with dyslipidemia (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1, 2.5), diabetes (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1, 2.4), and hypertension (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2, 3.0). We found no significant predictors for cilostazol use. Medication use did not differ over time in multivariate analyses.

Exercise or diet counseling was associated with obesity (OR 3.5, 95% CI 2.1, 6.1) and hypertension (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.9, 2.7) although the latter failed to reach statistical significance. Use of smoking cessation advice or medications was less likely in subjects ≥65 years of age (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1, 0.7), non-whites (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1, 0.9) and more likely in subjects with concomitant CAD (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.6, 7.4). Lifestyle counseling did not differ over time in multivariate analyses (Online Table 1).

Physician Type

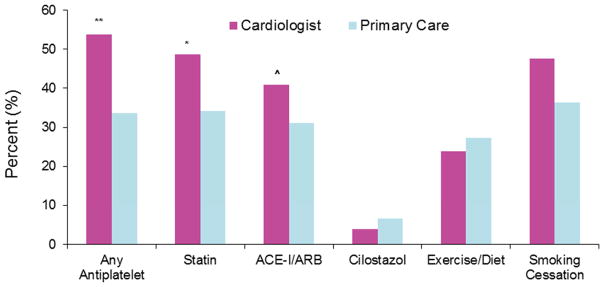

Since quality of care can be dependent by physician type,(19) we sought to investigate medication use and lifestyle counseling by practicing physician. Specialty data is not available in NHAMCS (hospital outpatient) and thus a separate sensitivity analysis was performed with NAMCS (physician office) data. Cardiologists and primary care physicians were the most likely groups taking care of these patients. As noted in Figure 3, PAD visits with a cardiologist were more likely to be on antiplatelet therapy, statins, ACE-inhibitors or ARBs, and more frequently counselled for smoking cessation (P<0.05 for all). After multivariate analysis, antiplatelet therapy was significantly more likely to be used in PAD when seen by a cardiologist (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1, 2.9). Use of statins, ACE-inhibitors or ARBs, and lifestyle counseling were not significantly different between groups.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of medication use and lifestyle counseling in patients with peripheral artery disease when seen by a cardiologist versus primary care.

Discussion

Peripheral artery disease is an increasingly common medical problem, and numerous clinical studies and guidelines have focused on its optimal treatment. To investigate the use of clinical guidelines, it is important to monitor physician practice patterns. The NAMCS and the NHAMCS provide unique insights into the clinical management of PAD in the United States over time. In the present study, we examined a representative sample of visits to physicians in the United States between 2006 and 2013 among patients with PAD. The proportion of visits reporting use of medical therapy and lifestyle counseling was low and appears suboptimal in consideration of the substantial benefit of secondary cardiovascular prevention and lifestyle counseling. These findings suggest that a considerable proportion of patients with PAD disease remain at increased risk for adverse outcomes.

Our findings clearly show the underuse of cardiovascular prevention medication in patients with PAD. It has been well documented that antiplatelet therapy and statins significantly reduce incident cardiovascular events in PAD (6,7). Although use of antiplatelet therapy and statins increased from 2006 to 2013, the magnitude of this increase was less than expected and this increase was not significant after adjusting for demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients. In multivariate analysis, sex and race/ethnicity of the patient did not play a role in the use of secondary prevention and lifestyle counselling. While we are unable to determine the reason for the underuse of secondary prevention and lifestyle counselling, interventions to optimize secondary prevention, such as physician note “checklists” or other systematic prescription programs, would likely improve medication use and lifestyle counselling (20,21).

While some, but not all, prior studies have reported comparatively higher rates of secondary prevention in patients with PAD, many of these studies focused on selected patients whose use of secondary prevention might be higher than that in the physician office setting assessed here (9,11,22). Studies of hospitalized patients have shown higher rates, likely due to the focused clinical attention that these patients receive. Hospitalized patients, however, constitute a minority of all patients with PAD. Practices in community settings may be more likely to reflect the public health impact of lifestyle recommendations and secondary prevention efforts.

Similar to prior studies, we demonstrate that secondary prevention use in PAD was not uniform across patient subpopulations. In particular, secondary prevention was less likely to be reported in patients with PAD alone (without concomitant CAD). While PAD and CAD represent a particularly high-risk group, patients with PAD alone are still at heightened risk for cardiovascular and limb events and impairment in quality of life. The greater use of secondary prevention medication in patients with PAD and CAD may indicate a higher use of medication in patients with polyvascular disease or the importance of secondary prevention in CAD irrespective of PAD. These data suggest important barriers to the uniform and widespread adoption of secondary prevention in PAD. The underuse of lifestyle recommendations and cardiovascular prevention in this population is a major concern and supports the need for better awareness and education for the vascular community.

Limitations

There are important limitations of this analysis. The NAMCS and NHAMCS provide a limited amount of clinical information on each patient visit; there is no data on the severity of PAD nor could we characterize the symptom status of the patient. Our estimates of medication use could also be lower than expected since underreporting of medication use and lifestyle counseling may have occurred, in particular, aspirin and diet counseling. The NAMCS and NHAMCS do not capture the longitudinal experience of the individual patients, and because the unit of measurement is by patient visit frequent users of care may be overrepresented. Finally, we are unable to determine specific reasons that patients are not taking medications, such as adverse drug reactions or patient preference. Thus, determining appropriateness of care is difficult. In addition, it may have been more appropriate to compare our patients with PAD and concurrent CAD to patients with CAD alone, but our analysis did not incorporate the latter cohort.

Conclusions

This analysis suggests that use of secondary prevention and lifestyle counseling in patients with PAD has not become a widely disseminated practice in the United States, a finding consistent with a global pattern (9,11,12). Our study identifies important targets for immediate improvement of health care outcomes in patients with PAD. New health care system strategies are required to ensure adequate resource utilization in patients with PAD. While much attention is focused on novel therapies in PAD, a refocus on established therapies and healthy behaviors is clearly needed. Attempts to increase patient and physician awareness of the benefits of lifestyle recommendations and secondary prevention may be necessary. In addition, systems of chronic disease management in which the use of nurses, other health care providers, or information systems complements the role of physicians also may be helpful. Finally, efforts to monitor the prevention practices taking care of PAD patients may provide new incentives for quality care. The personal, societal, and financial burdens of preventable deterioration of patients with PAD suggest that a substantial investment in such strategies may be warranted. Future research aimed at improving secondary prevention and lifestyle counseling in patients with PAD are certainly needed.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Central Illustration: Cardiovascular Prevention in Peripheral Artery Disease.

Clinical Perspectives.

Competency in Systems-Based Practice

Guideline-recommended measures for lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events are utilized in fewer than half the patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) managed in ambulatory care practice.

Translational Outlook

More work is needed to develop systems of care that promulgate evidence-based interventions to improve clinical outcomes in this high-risk patient population.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ladapo had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Berger was supported, in part, by the National Heart and Lung Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01HL114978). Dr. Ladapo was supported by a K23 Career Development Award (K23 HL116787) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (74140).

Abbreviations

- ACE-I

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blockers

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- NAMCS

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- NHAMCS

National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- PAD

peripheral artery disease

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Berger receives research funding from Astra Zeneca and served on the Executive Committee for the EUCLID trial of antiplatelet therapy in patients with peripheral artery disease. He also receives consulting fees from Janssen and Merck. Dr. Ladapo has no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:1329–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savji N, Rockman CB, Skolnick AH, et al. Association between advanced age and vascular disease in different arterial territories: a population database of over 3. 6 million subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1736–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Writing Group M. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:1509–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subherwal S, Patel MR, Kober L, et al. Peripheral artery disease is a coronary heart disease risk equivalent among both men and women: results from a nationwide study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:317–25. doi: 10.1177/2047487313519344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger JS, Hiatt WR. Medical therapy in peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2012;126:491–500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.033886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hivert MF, Arena R, Forman DE, et al. Medical Training to Achieve Competency in Lifestyle Counseling: An Essential Foundation for Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases and Other Chronic Medical Conditions: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e308–e327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cacoub PP, Abola MT, Baumgartner I, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor control and outcomes in peripheral artery disease patients in the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:e86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, Creager MA. Secondary prevention and mortality in peripheral artery disease: National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, 1999 to 2004. Circulation. 2011;124:17–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subherwal S, Patel MR, Kober L, et al. Missed Opportunities Despite Improvement in Use of Cardioprotective Medications Among Patients With Lower-Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease, Underuse Remains. Circulation. 2012;126:1345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.108787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacoub PP, Zeymer U, Limbourg T, et al. Effects of adherence to guidelines for the control of major cardiovascular risk factors on outcomes in the REduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry Europe. Heart. 2011;97:660–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.213710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.) Ambulatory Health Care Data: NAMCS and NHAMCS description. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.) 2009 NAMCS Public-use Data File Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch AT, Allison MA, Gomes AS, et al. A Call to Action: Women and Peripheral Artery Disease A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Endorsed by the Vascular Disease Foundation and its Peripheral Artery Disease Coalition. Circulation. 2012;125:1449–1472. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824c39ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladapo JA, Blecker S, Douglas PS. Physician decision making and trends in the use of cardiac stress testing in the United States: an analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:482–90. doi: 10.7326/M14-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigmund AE, Stevens ER, Blitz JD, Ladapo JA. Use of Preoperative Testing and Physicians’ Response to Professional Society Guidance. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1352–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.) Ambulatory Health Care Data: NAMCS and NHAMCS, Reliability of Estimates. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donohoe MT. Comparing generalist and specialty care: discrepancies, deficiencies, and excesses. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1596–608. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cebul RD, Love TE, Jain AK, Hebert CJ. Electronic health records and quality of diabetes care. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:825–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1102519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jepson RG, Harris FM, Platt S, Tannahill C. The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: a review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong EJ, Chen DC, Westin GG, et al. Adherence to guideline-recommended therapy is associated with decreased major adverse cardiovascular events and major adverse limb events among patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000697. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.