Abstract

Background

Tolvaptan, a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to reduce the rates of growth in total kidney volume (TKV) and renal function loss in ADPKD patients, but also leads to polyuria because of its aquaretic effect. Prolonged polyuria can result in ureter dilatation with consequently renal function loss. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the effect of tolvaptan-induced polyuria on ureter diameter in ADPKD patients.

Methods

70 ADPKD patients were included (51 were randomized to tolvaptan and 19 to placebo). At baseline and after 3 years of treatment renal function was measured (mGFR) and MRI was performed to measure TKV and ureter diameter at the levels of renal pelvis and fifth lumbar vertebral body (L5).

Results

In these patients [65.7 % male, age 41 ± 9 years, mGFR 74 ± 27 mL/min/1.73 m2 and TKV 1.92 (1.27–2.67) L], no differences were found between tolvaptan and placebo-treated patients in 24-h urine volume at baseline (2.5 vs. 2.5 L, p = 0.8), nor in ureter diameter at renal pelvis and L5 (4.0 vs. 4.2 mm, p = 0.4 and 3.0 vs. 3.1 mm, p = 0.3). After 3 years of treatment 24-h urine volume was higher in tolvaptan-treated patients when compared to placebo (4.7 vs. 2.3 L, p < 0.001), but no differences were found in ureter diameter between both groups (renal pelvis: 4.2 vs. 4.4 mm, p = 0.4 and L5: 3.1 vs. 3.3 mm, p = 0.4).

Conclusions

Tolvaptan-induced polyuria did not lead to an increase in ureter diameter, suggesting that tolvaptan is a safe therapy from a urological point of view.

Keywords: Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, Tolvaptan, Polyuria, Ureter

Introduction

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) has a diagnosed prevalence of approximately 3–4 per 10,000 in the general population and is characterized by progressive cyst formation in both kidneys and renal function loss [1, 2]. It is the fourth most common cause of end-stage renal disease for which renal replacement therapy is the only therapeutic option [3]. The TEMPO 3:4 trial publication recently showed renoprotective effects of tolvaptan therapy in a randomized controlled clinical trial setting [4]. During 3 years of follow-up the vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist tolvaptan decreased the rate of growth in total kidney volume and the rate of renal function loss compared to placebo. Due to its aquaretic effect tolvaptan causes polyuria that sometimes can be severe. In some ADPKD patients tolvaptan use could result to a urine output up to 8–10 L per day.

Patients with prolonged polyuria should be used to void more frequently since the maximum bladder capacity is reached earlier. Infrequent and inconstant voiding could easily lead in these patients to an accumulation of urine retention with more often higher intravesical pressure. Consequently this may result to higher pressure in the upper urinary tract which can cause ureter dilatation, hydronephrosis and ultimately renal function loss. This mechanism from polyuria to renal function loss has already been described several times in literature in patients with (nephrogenic) diabetes insipidus and psychogenic polydipsia [5–11]. To reduce the risk of these problems, patients with polyuria are therefore advised to void more frequently [5].

ADPKD patients who use tolvaptan potentially have the risk of developing similar problems. Hypothetically, it could be that in some patients the beneficial effect of tolvaptan with respect to kidney function preservation is partially offset due to these urological side effects. The aim of the present study was therefore to investigate the effect of tolvaptan-induced polyuria, assessed as 24-h urine volume, on the ureter diameter in patients with ADPKD.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

The present study was performed as a post hoc exploratory analysis of ADPKD patients that were included in the TEMPO 3:4 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00428948) and 284 trial (NCT01336972) in the University Medical Center Groningen. All participating patients of the TEMPO 3:4 trial were included (n = 51) and 19 of the 27 patients from the 284 study, because only 19 patients had used tolvaptan for at least 12 months. Details of both study protocols [12] and the primary study results [4, 13] have been published previously. Patients were included in the TEMPO 3:4 trial if they were 18–50 years old, had a total kidney volume (TKV) measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) ≥750 mL and creatinine clearance estimated (eCrCl) by the Cockcroft-Gault formula ≥60 mL/min. ADPKD patients between 18 and 70 years were included in the 284 trial and were assigned by estimated GFR (eGFR) in three groups (group 1: eGFR >60; group 2: eGFR 30–60; group 3: eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2). Exclusion criteria for both studies were most importantly concomitant illnesses likely to confound endpoint assessments, such as diabetes mellitus and previous use of tolvaptan.

In the TEMPO 3:4 trial, patients were randomized to tolvaptan or placebo (2:1) with stratification by hypertension status, eCrCl and TKV. Tolvaptan dosing was started at 45 mg am/15 mg pm (daily split-dose) and increased weekly to 60/30 and 90/30 mg, if tolerated. Patients remained on the highest tolerated dose for 36 months. Patients in the 284 trial used open-label tolvaptan, dosing started at 45 mg am/15 mg pm and increased weekly to 60/30 and 90/30 mg if tolerated. After completing the TEMPO 3:4 trial and 284 trial, all patients were offered to continue tolvaptan use in the open-label tolvaptan study (TEMPO 4:4 trial, NCT01214421). All studies were performed in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Data collection and measurements

All patients routinely collected a 24-h urine sample the day preceding the baseline assessment. Fasting blood samples were drawn for determination of creatinine and estimated GFR (eGFR) was applied by the CKD-EPI equation [14]. After blood samples were drawn, renal function measurements were performed using the constant infusion method with 125I-iothalamate to measure glomerular filtration rate (mGFR) [15, 16]. MR imaging was performed immediately after renal function measurement (around 5 pm) using a standardized abdominal MR imaging protocol without the use of intravenous contrast [17]. Per protocol patients took their afternoon tolvaptan dose at 4 pm, so MR imaging was performed within 1.5 h after tolvaptan administration. 56 patients were scanned on a 1.5-Tesla MR (Magnetom Avento, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and 14 patients on a 3-Tesla research MR scanner (Intera, Philips, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). TKV was assessed using Analyze Direct 8.0 software (AnalyzeDirect, Inc., Overland Park, KS, USA). After 3 years, MR imaging as well as renal function measurements were performed again per protocol in the Tempo 3:4 trial, with patients still being on treatment.

The MR images on baseline and after 3 years of treatment were used to assess anatomy of the urinary tract and to measure ureter diameter. MR imaging is, among others, a valuable and accurate imaging method for evaluating the urinary tract system including the ureter [18–21]. Ureter diameter was measured, preferably on the coronal T2-half Fourier single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) (Fig. 1). Ureter diameter was measured at both sides at two places (3 cm distally from the pyelo-ureteral junction as well as at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebral body: L5) as the diameter of the ureter measured perpendicular from ureter wall to ureter wall. Normal diameter of the ureter is 3–5 mm. Ureter dilation was defined as a ureter diameter >7 mm according to the prevailing classification system [22, 23].

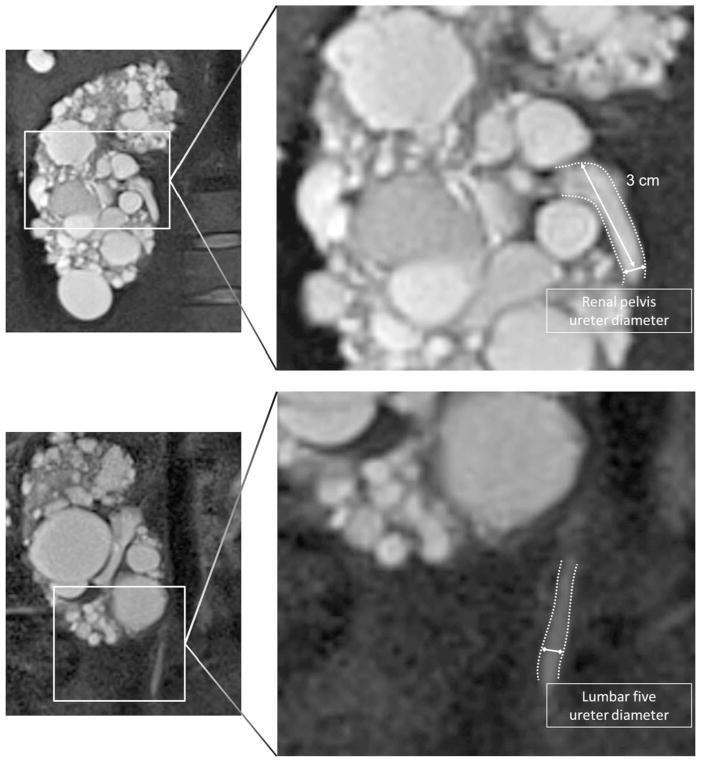

Fig. 1.

Ureter diameter was measured 3 cm after the pyelo-ureteral junction (upper panel) and on the level of L5 (lower panel), perpendicular from ureter wall to ureter wall, preferably on the coronal T2-half Fourier single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) sequence. White lines indicate the place of measurement

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were calculated for the overall population and for both treatment groups separately. Parametric variables are expressed as mean ± SD, non-parametric variables as median (IQR). Differences in baseline characteristics between the two treatment groups were calculated with a Chi-square test for categorical data, and for continuous data with Student’s t test or a Mann-Whitney U test in case of non-parametric data.

To investigate reliability of ureter diameter measurement on MR images, we assessed intra- and inter-observer variability. Two physicians were trained to measure ureter diameter. In a test set of ten patients, ureter diameter was measured twice at baseline as well as at the end of the study. The physicians were blinded for their previous measurement results. These results were analysed to calculate intra- and inter-observer coefficients of variation (CV). Inter-CV was calculated as the SD of ureter diameter values measured by two observers in the ten subjects divided by the mean ureter diameter of those subjects multiplied by 100 %. The intra-CV was calculated as SD of ureter diameter values measured by a single observer divided by the mean ureter diameter of single observer multiplied by 100 %.

Pearson’s Chi-squared test was used to assess differences in prevalence of a dilated ureter (defined as a ureter with exceeding 7 mm [22, 23]) between the placebo group and the tolvaptan group at baseline and after 3 years of treatment. Paired t tests were used to compare ureter diameter at baseline and 3 years of treatment, whereas unpaired t tests were used to assess any differences in ureter diameter between placebo and tolvaptan-treated patients at baseline and after 3 years of treatment.

Furthermore, univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to investigate which variables were associated with ureter diameter (defined as mean diameter at renal pelvis and L5). Determinants were, among others, patient characteristics (e.g., sex and age), use of tolvaptan and 24-h urine volume. Determinants with p < 0.1 in univariate analyses were selected for multivariate analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (SPSS Statistics, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A 2-tailed p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 70 patients with ADPKD were included, of which 51 used tolvaptan and 19 patients placebo. Overall, patients were 41 ± 9 years old and 65.7 % were male. Table 1 also shows the patient characteristics stratified according to tolvaptan and placebo use. No significant differences in characteristics were observed between these two groups, except for age. Patients in the placebo group were slightly younger (p = 0.03).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| All | Placebo | Tolvaptan | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 70 | 19 | 51 | – |

| Age (years) | 41 ± 9 | 37 ± 6 | 42 ± 9 | 0.03 |

| Male sex (%) | 65.7 | 63.2 | 66.7 | 0.8 |

| Length (cm) | 181 ± 11 | 181 ± 11 | 181 ± 10 | 0.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 86 ± 15 | 85 ± 14 | 86 ± 14 | 0.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.2 ± 3.5 | 25.7 ± 3.9 | 26.3 ± 3.3 | 0.5 |

| Antihypertensive use (%) | 84.3 | 78.9 | 86.3 | 0.5 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 132 ± 11 | 132 ± 11 | 132 ± 11 | 0.9 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82 ± 8 | 82 ± 7 | 83 ± 9 | 0.7 |

| Heart rate (per min) | 68 ± 12 | 66 ± 11 | 69 ± 12 | 0.3 |

| Plasma creatinine (μmol/L) | 117 ± 57 | 106 ± 39 | 121 ± 62 | 0.3 |

| mGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 74 ± 27 | 80 ± 24 | 72 ± 28 | 0.2 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 69 ± 27 | 73 ± 21 | 68 ± 29 | 0.5 |

| Total kidney volume (L) | 1.92 (1.27–2.67) | 1.68 (1.13–2.37) | 2.03 (1.31–2.67) | 0.3 |

mGFR measured glomerular filtration rate, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

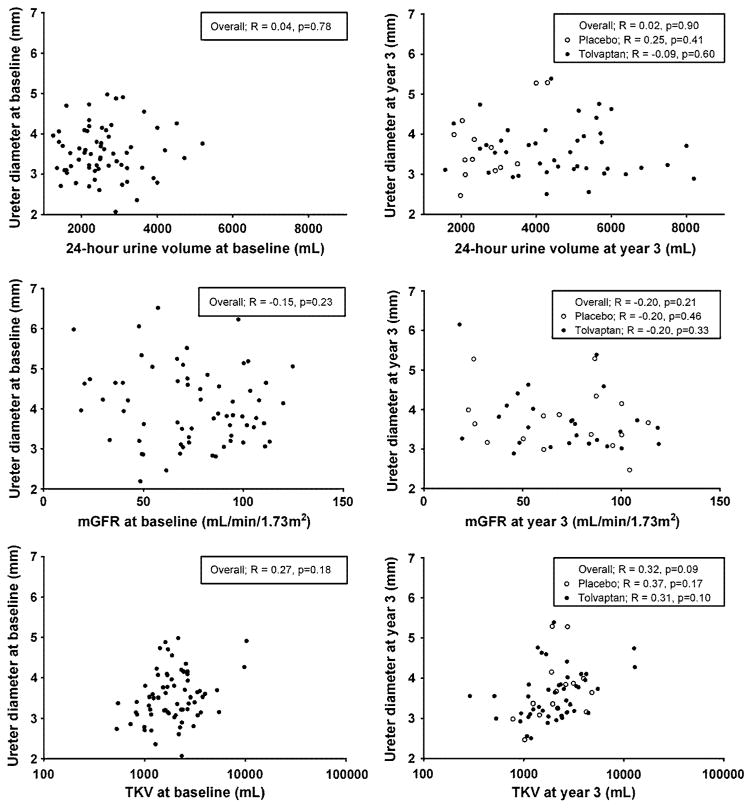

At baseline, no differences were found between tolvaptan and placebo-treated patients in 24-h urine volume [2.46 (2.08–2.72) vs. 2.50 (1.94–3.08) L, p = 0.8] (Table 2). Ureter diameter was measured in all patients except for two, because their ureters were not depicted on MR images. At baseline 2 patients had a dilated ureter, one patient left-sided, and one patient right-sided. No significant difference in ureter diameter was found between tolvaptan and placebo-treated patients (renal pelvis: 4.0 ± 0.9 vs. 4.2 ± 1.1 mm, p = 0.3 and L5: 3.0 ± 0.5 vs. 3.1 ± 0.4 mm, p = 0.2, respectively). Mean baseline ureter diameter was not associated with baseline 24-h urine volume, neither in a crude analysis nor after adjustment for age, sex, TKV and mGFR (p = 0.8 and p = 0.4, respectively) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, no association was found between baseline ureter diameter and baseline TKV or mGFR.

Table 2.

Ureter diameter subdivided in placebo group (n = 19) and tolvaptan group (n = 51)

| Baseline | Year 3 | Change | p value, base vs. year 3 | p value, P vs. T year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h urine volume (L) | |||||

| Placebo | 2.50 (2.08–2.72) | 2.33 (2.08–2.16) | 0.09 (−0.38 to 0.96) | 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Tolvaptan | 2.46 (1.94–3.08) | 4.74 (3.34–5.68) | 2.08 (1.08–3.03) | <0.001 | |

| Renal pelvis left (mm) | |||||

| Placebo | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Tolvaptan | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 1.0 | 0.8 | |

| Renal pelvis right (mm) | |||||

| Placebo | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 0.2 ± 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Tolvaptan | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 1.1 | 0.2 | |

| Ureter L5 left (mm) | |||||

| Placebo | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Tolvaptan | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.7 | 0.3 | |

| Ureter L5 right (mm) | |||||

| Placebo | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 0.0 ± 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Tolvaptan | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 0.2 ± 1.1 | 0.2 | |

Base baseline, P placebo, T tolvaptan

Fig. 2.

Associations of 24-h volume (upper panels), measured glomerular filtration rate (middle panels) or total kidney volume (log scale, lower panels) with ureter diameter at baseline (left panels) and at year 3 (right panels)

Ureter assessment during follow-up

After 36 months of treatment, 24-h urine volume was significantly higher in tolvaptan-treated patients [4.74 (3.34–5.68) vs. 2.33 (2.08–2.16) L, p < 0.001] (Table 2). One patient had a dilated ureter right-sided. This was a patient from the placebo group and had at baseline a ureter diameter of 5.9 mm and after 3 years of 8.4 mm at the level of the renal pelvis. No significant differences in ureter diameter were found between baseline and after 3 years in the 51 tolvaptan-treated patients for ureter diameter measurements at renal pelvis and L5 right as well as left-sided (Table 2). In addition, no differences were found in ureter diameter between both treatment groups after 3 years (renal pelvis: 4.1 ± 1.0 vs. 4.4 ±1.2 mm, p = 0.4 and L5: 3.1 ± 0.7 vs. 3.3 ± 0.7 mm, p = 0.4). No significant association was found between ureter diameter and 24-h urine volume at year 3, neither in a crude analysis nor in a multivariate model adjusting for age, sex, TKV and mGFR (p = 0.9 and p = 1.0, respectively) (Fig. 2). Ureter diameter at year 3 was also not associated with TKV and mGFR. Tolvaptan use led to a decreased kidney growth, annual change in TKV was significantly lower in the tolvaptan-treated patients (2.7 vs. 6.0 %, p = 0.003). We did not find an association between annual change in TKV and ureter diameter (p = 0.2).

After 3 years of treatment with study medication in the TEMPO 3:4 trial, we offered our patients to participate in the open-label tolvaptan study (TEMPO 4:4 trial, NCT01214421). From the initial 51 patients, 32 patients used tolvaptan and 19 patients used placebo. From these 32 patients, 22 patients were followed for an average of 3.6 ± 0.8 years and again MR imaging was performed. Their 24-h urine volume was still significantly higher compared to their baseline volume [2.45 (2.02–2.91) vs. 5.13 (3.24–5.90) L, p < 0.001]. No significant differences in ureter diameter were found between ureter diameter at baseline and at follow-up in these 22 tolvaptan-treated patients for ureter diameter measurements at the renal pelvis and L5, right as well as left-sided (renal pelvis left: 3.7 ± 0.9 vs. 3.7 ± 0.7 mm, p = 0.7; renal pelvis right: 4.1 ± 1.2 vs. 3.9 ± 0.7 mm, p = 0.3; L5 left: 3.1 ± 0.7 vs. 3.1 ± 0.6 mm, p = 0.9 and L5 right 3.0 ± 0.6 vs. 3.1 ± 0.8 mm, p = 0.4).

Sensitivity analysis

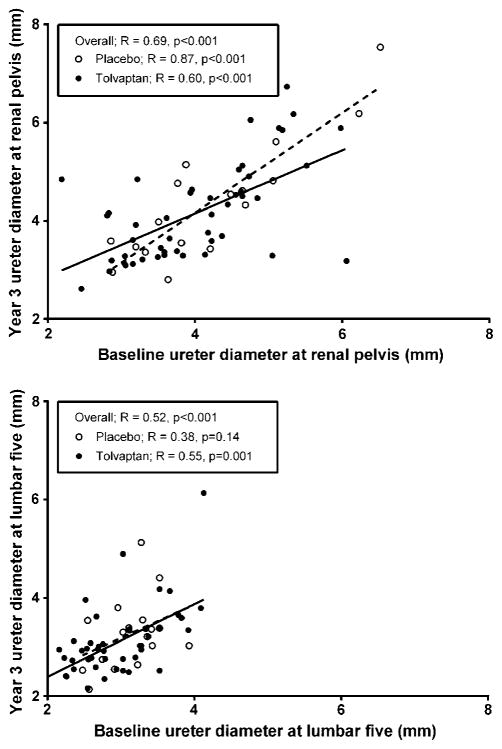

For sensitivity analysis of the ureter measurement, intra-and inter-reviewer coefficients of variation for ureter measurement were 6.4 and 7.2 %, respectively, and did not differ when measured on the level of the renal pelvis level or L5, nor between left- or right-sided ureters. The association between baseline ureter diameter and ureter diameter at the end of the study is shown in Fig. 3. As depicted, baseline ureter diameter at the renal pelvis was strongly correlated with ureter diameter at the end of the study in the overall group, as well as in tolvaptan and placebo-treated patients (overall R = 0.69, p < 0.001; tolvaptan R = 0.60, p = 0.012; placebo R = 0.87, p < 0.001). At the level of L5 baseline ureter diameter was also associated with ureter diameter at the end of the study (overall R = 0.52, p < 0.001). This indicated and supported that ureter diameter measurements were reproducible and could be measured adequately on MRIs that were performed for TKV measurement in ADPKD patients.

Fig. 3.

Associations of ureter diameter at baseline with ureter diameter at year 3 in ADPKD patients at the level of the renal pelvis (upper panel) and lumbar 5 (lower panel) [overall n = 70, tolvaptan use n = 51 (solid line), placebo use n = 19 (dashed line)]

Of note, the results of the sensitivity analyses (i.e., analyses stratified for sex) were essentially similar to the results of the primary analyses. When eGFR was studied instead of mGFR, similar results were obtained. Lastly, there were no significant interaction terms of 24-h urine volume with sex and age in the analyses, with ureter diameter at the end of study as dependent variable (p = 0.6 and p = 0.8, respectively).

Discussion

The present study shows that tolvaptan-induced polyuria did not lead to an increase in ureter diameter after 3 years of tolvaptan treatment, suggesting that tolvaptan did not cause high pressure in the upper urinary tract which can lead to renal function loss.

Up to 2014, no treatment options were available to modify the course of disease progression in ADPKD. In 2007, the first large-scale randomized controlled trial, the TEMPO 3:4 trial, started with a potential therapeutic drug, tolvaptan, in ADPKD patients [4]. For the first time, a medical treatment proved to be beneficial with respect to kidney outcomes. In 1445 ADPKD patients with a preserved kidney function, treatment with tolvaptan reduced the rate of growth in TKV by 49 % and the rate of eGFR loss by 26 % compared with placebo [4]. Despite of these promising results, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) decided against approval of tolvaptan for the indication of slowing disease progression in ADPKD. Whereas the FDA decided not to register tolvaptan, it is recently been approved in Japan, Canada and Europe.

Patients who received tolvaptan had, as expected, a higher frequency of adverse events related to increased aquaresis (thirst, polyuria, nocturia, and polydipsia, as a result of the excretion of electrolyte-free water). The urine output was highly increased, even up to 10 L per day. In normal conditions, contractions in the ureter wall cause peristaltic waves that transport the urine from the collecting ducts via the renal pelvis and ureter into the bladder. To enter the bladder, the intra-ureteric pressure should be higher than the intravesical pressure. In case of prolonged polyuria and inconstant and infrequent voiding, the intravesical pressure increases by the persistent accumulation of urine in the bladder. In this situation the ureteric pressure is too low for the urine to enter the bladder resulting in decompensation, ureter dilatation and hydronephrosis [8].

Prolonged polyuria as cause of ureter dilatation and bilateral non-obstructive hydronephrosis has been documented in patients with (nephrogenic) diabetes insipidus and psychogenic polydipsia [5–11]. This phenomenon was not only been observed in adult diabetes insipidus patients with polyuria since childhood, but also in adult patients with polyuria for only 3–5 years [11, 24]. Interestingly, some patients had large bladder volumes and hydronephrosis by radiological investigations, while others did not have an increased bladder volume. However, their renal function already declined because of hydronephrosis. This indicated and supported that persistent polyuria itself could cause dilatation of the urinary tract, which could also be a theoretical issue in tolvaptan-treated patients.

To our knowledge, no studies have been performed to investigate the effect of polyuria on ureter diameter in ADPKD patients. Our study results are supported by previous studies published in renal transplant literature. It has been shown that one kidney can process an increased fluid load up to 4 L per day without developing structural or functional defects in the renal pelvis or ureter as well as progressive kidney function decline [25, 26].

Since tolvaptan is recently approved in Japan, Canada and Europe, we are aware that this theoretical problem of tolvaptan exists and clinicians should therefore inform their ADPKD patients, who use tolvaptan, about the potential urological effects. Patients are instructed to void more frequently than usual. When they feel the urge to void, they should not ignore their voiding tendency.

In addition, ADPKD patients on tolvaptan have to avoid drugs that diminish, at least the sense of, bladder contractility like anticholinergic drugs [27]. Long-term use of anticholinergic drugs in combination with polyuria could potentially lead to urological problems of bladder distension and hydronephrosis [11]. Lastly, patients with known obstructive lower urinary tract symptoms should be informed that the combination of polyuria and these symptoms might lead to an increased risk of renal failure [28].

We acknowledge that this study has limitations. First, a relatively small number of patients was included, which may lead to false-negative conclusions. Only patients from our centre were included in this study, because this data was readily available to investigate this issue for the first time and our centre has the highest number of ADPKD patients on tolvaptan treatment in the world. However, to exclude the risk for ureter dilatation in tolvaptan-treated patients, ureter diameter should be assessed in all participating patients in the TEMPO 3:4 trial. Second, ureter diameter depends on ureteral peristalsis, bladder pressure and filling. Ureter diameter varies from time to time; however, ureter diameter may be steadily dilated when the physiological peristaltic movement is hampered by prolonged polyuria. Unfortunately, we did not have information about the bladder filling, because the bladder was not depicted on the MR images. Third, the way the ureter was measured is not the gold standard method, which is intravenous pyelography or MR urography. The present study was a post hoc exploratory analysis of ADPKD patients that were included in the TEMPO 3:4 trial and 284 trial. Per protocol only MR imaging was performed for TKV assessment; therefore, no intravenous pyelography or MR urography was performed. However, the way the ureter was measured seems to be a reliable method because we found a strong association between ureter diameter at baseline and after 3 years tolvaptan use in our population and intra- and inter-observer variability were relatively low. Furthermore, among others, MR imaging is considered as a valuable and accurate imaging tool for evaluating the urinary tract system including the ureter [18–21]. Fourth, no data was available about the micturition frequency and volume. Lastly, our negative findings could be caused by a too short follow-up. Patients with diabetes insipidus could have polyuria from childhood. However, our study patients had polyuria only for 3 years, but also patients with a longer follow-up time of more than 6 years (n = 22) were investigated with no significant increase in ureter diameter. Furthermore, previous studies reported that short-term polyuria could also lead to urological involvement [10, 11, 24, 29].

In conclusion, our data suggest that tolvaptan is safe from a urological point of view. Because of the limited power of our study, a larger scale investigation needs to be performed to exclude that tolvaptan-induced polyuria can lead to the development of an increase in ureter diameter in ADPKD. Until such data become available we still advise, when tolvaptan is prescribed as a treatment option in ADPKD, that patients should be instructed to void frequently.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee at which the studies were conducted (IRB approval number METc2006.285, METc2010.173 and METc2010.187) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Neumann HP, Jilg C, Bacher J, et al. Epidemiology of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: an in-depth clinical study for south-western Germany. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1472–87. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higashihara E, Nutahara K, Kojima M, et al. Prevalence and renal prognosis of diagnosed autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Japan. Nephron. 1998;80:421–7. doi: 10.1159/000045214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grantham JJ. Clinical practice. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1477–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2407–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Lieburg AF, Knoers NV, Monnens LA. Clinical presentation and follow-up of 30 patients with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(9):1958–64. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1091958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hora M, Reischig T, Hes O, et al. Urological complications of congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus—long-term follow-up of one patient. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38:531–2. doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-0093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higuchi A, Kawamura T, Nakai H, et al. Infrequent voiding in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus as a cause of renal failure. Pediatr Int. 2002;44:540–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2002.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korzets A, Sachs D, Gremitsky A, et al. Unexplained polyuria and non-obstructive hydronephrosis in a urological department. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2410–2. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison RB, Ramchandani P, Allen JT. Psychogenic polydipsia: unusual cause for hydronephrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:327–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.133.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maroz N, Maroz U, Iqbal S, et al. Nonobstructive hydronephrosis due to social polydipsia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:376–8. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh H, Linas SL. Compulsive water drinking in the setting of anticholinergic drug use: an unrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:586–9. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90593-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres VE, Meijer E, Bae KT, et al. Rationale and design of the TEMPO (tolvaptan efficacy and safety in management of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and its outcomes) 3–4 Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:692–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boertien WE, Meijer E, de Jong PE, et al. Short-term renal hemodynamic effects of tolvaptan in subjects with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease at various stages of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;84:1278–86. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donker AJ, van der Hem GK, Sluiter WJ, et al. A radioisotope method for simultaneous determination of the glomerular filtration rate and the effective renal plasma flow. Neth J Med. 1977;20:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apperloo AJ, de Zeeuw D, Donker AJ, et al. Precision of glomerular filtration rate determinations for long-term slope calculations is improved by simultaneous infusion of 125I-iothalamate and 1311-hippuran. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:567–72. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V74567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae KT, Commean PK, Lee J. Volumetric measurement of renal cysts and parenchyma using MRI: phantoms and patients with polycystic kidney disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:614–9. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masselli G, Derme M, Laghi F, et al. Imaging of stone disease in pregnancy. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:1409–14. doi: 10.1007/s00261-013-0019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blomlie V, Rofstad EK, Trope C, Lien HH. Critical soft tissues of the female pelvis: serial MR imaging before, during, and after radiation therapy. Radiology. 1997;203:391–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.2.9114093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verswijvel GA, Oyen RH, Van Poppel HP, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of urologic disease: an all-in-one approach. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1614–9. doi: 10.1007/s003300000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhargava P, Dighe MK, Lee JH, Wang C. Multimodality imaging of ureteric disease. Radiol Clin N Am. 2012;50:271–99. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiro FI, Fry IK. Ureteric dilatation in nonpregnant women. Proc R Soc Med. 1970;63:462–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zelenko N, Coll D, Rosenfeld AT, et al. Normal ureter size on unenhanced helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1039–41. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.4.1821039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blum A, Friedland GW. Urinary tract abnormalities due to chronic psychogenic polydipsia. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:915–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.7.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber M, Berglund D, Reule S, et al. Daily fluid intake and outcomes in kidney recipients: post hoc analysis from the randomized ABCAN trial. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:261–7. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zermann DH, Loffler U, Reichelt O, et al. Bladder dysfunction and end stage renal disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003;35:93–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1025910025216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres VE, Bankir L, Grantham JJ. A case for water in the treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1140–50. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00790209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European Medicines Agency. [Accessed 10 Nov 2015];Summary of medicinal product characteristics Jinarc. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002788/WC500187921.pdf.

- 29.Jin XD, Chen ZD, Cai SL, et al. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with dilatation of bilateral renal pelvis, ureter and bladder. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43:73–5. doi: 10.1080/00365590802580208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]