Abstract

Objective

Epilepsy is commonly seen in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC). The relationship between seizures and developmental outcomes has been reported, but few studies have examined this relationship in a prospective, longitudinal manner. The objective of the study was to evaluate the relationship between seizures and early development in TSC.

Methods

Analysis of 130 patients ages 0–36 months with TSC participating in the TSC Autism Center of Excellence Network, a large multicenter, prospective observational study evaluating biomarkers predictive of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), was performed. Infants were evaluated longitudinally with standardized evaluations, including cognitive, adaptive, and autism-specific measures. Seizure history was collected continuously throughout, including seizure type and frequency.

Results

Data were analyzed at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of age. Patients without a history of seizures performed better on all developmental assessments at all time points compared to patients with a history of seizures and exhibited normal development at 24 months. Patients with a history of seizures not only performed worse, but developmental progress lagged the non-seizing group. All patients with a history of infantile spasms performed worse on all developmental assessments at 12, 18, and 24 months. Higher seizure frequency correlated with poorer outcomes on developmental testing at all time points, but particularly at 12 months and beyond. Patients with higher seizure frequency during infancy continued to perform worse developmentally through 24 months. A logistic model looking at the individual impact of infantile spasms, seizure frequency, and age of seizure onset as predictors of developmental delay revealed that age of seizure onset was the most important factor in determining developmental outcome.

Conclusions

Results of this study further define the relationship between seizures and developmental outcomes in young children with TSC. Early seizure onset in infants with TSC negatively impacts very early neurodevelopment, which persists through 24 months of age.

Keywords: Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, Epilepsy, Seizures, Infantile Spasms, Cognitive development, autism spectrum disorder

1. INTRODUCTION

Tuberous Sclerosis complex (TSC) is a genetic disorder that affects multiple organ systems and is present in approximately 1 in 6000 individuals [1]. Neurologic manifestations are the most common with epilepsy affecting approximately 80% of individuals, two-thirds of which begin developing epilepsy in the first year of life [2]. Neurodevelopmental disorders, including intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and behavioral difficulties, also are highly prevalent, affecting about 50% of individuals with TSC [3–5].

The association between early age at seizure onset and poor neurodevelopmental outcome has been consistently reported [6, 7]. Type and severity of seizures, especially infantile spasms, along with early age of seizure onset also appear to be associated with increased likelihood of cognitive and behavioral difficulties particularly if seizures are not controlled [8–12]. Similar associations have been reported for higher risk for ASD in TSC [9, 13–15], and it has been suggested that epilepsy may be an independent predictor of intellectual ability in TSC [7, 10, 16]. At this time, it is unclear as to whether neurodevelopmental disorders are caused by the underlying brain abnormalities seen in TSC, subsequent development of epilepsy, or both [17]. Few studies have looked at the relationship between seizures and developmental and behavioral outcomes in a prospective, longitudinal manner and lack detailed phenotypic characterization of development in the earliest years of life, when seizures and epilepsy first emerge.

By evaluating the temporal relationship between epilepsy onset and developmental functioning before and after seizures first emerge, our aim was to better define the association between neurodevelopmental outcome and epilepsy in infants and toddlers diagnosed with TSC. Here we report analysis of 130 patients ages 0–36 months with TSC participating in the TSC Autism Center of Excellence Network (TACERN), a large multicenter, prospective observational study to identify clinical, structural, and electrophysiological biomarkers predictive of ASD. Through serial developmental assessments and continuous seizure reporting, we are able to report in-depth characterization and temporal evolution of the developmental profile of infants with TSC over the first two years of life and explore the real-time impact of seizures during this critical phase of neurodevelopment.

2. METHODS

2.1 Subject recruitment

Infants with TSC were enrolled into TACERN (clinical trials.gov, NCT 01780441) at one of five sites across the United States (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Boston Children’s Hospital, University of Alabama at Birmingham, University of California at Los Angeles, and McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston). IRB approval was obtained at each of the five sites, and informed consent was acquired from all participating families prior to enrollment.

Inclusion criteria for the study consisted of the following: 1) age 3–12 months at time of enrollment; 2) meets clinical or genetic criteria for definitive diagnosis of TSC [18]. Patients were excluded if: 1) gestational age was <36 weeks at the time of delivery with significant perinatal complications (i.e. respiratory support, confirmed infection, intraventricular hemorrhage, cardiac compromise); 2) they had taken an investigational drug as part of another research study within 30 days prior to study enrollment; 3) were taking an mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin, sirolimus, or everolimus) orally at the time of study enrollment; 4) had a Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytoma (SEGA) requiring medical or surgical treatment; 5) had a history of epilepsy surgery; 6) or had any contraindications to MRI scanning.

2.2 Study Design

TACERN subjects were evaluated longitudinally at ages 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months. At each age, children underwent standardized evaluations, using developmental and adaptive measures. Clinical data was collected at enrollment and at each subsequent time point including basic demographics, medical and family history, participation in therapies (including type and frequency), past and current seizure history (using patient diaries collected and reviewed at every visit, as described in additional detail below), concomitant medications, and medical co-morbidities were recorded to determine if specific clinical factors modify the course of development. A physical examination from which clinical findings were recorded was performed at each visit. Although not the focus of the current analysis, EEG and MRI also were obtained at scheduled intervals as part of the TACERN study. A yearly calibration meeting was held to ensure developmental assessment reliability across all sites for the entire study period.

2.3 Developmental and behavioral assessments

Developmental assessments at each visit were carried out by a licensed psychologist and/or speech therapist blinded to patient’s clinical and seizure history at the time of testing and who had obtained research reliability on diagnostic (e.g., ADI-R and ADOS-2) and experimental (e.g., AOSI, ESCS) measures included in this project. All personnel were certified as being research-reliable on these measures. Developmental functioning at each visit was assessed using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL)[19]. The MSEL consists of five domains (gross motor, fine motor, expressive language, receptive language, and visual reception) and also provides an overall composite score. Adaptive functioning was assessed using the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd Edition, Survey Interview (VABS) and was completed at 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months [20]. The VABS is a caregiver-interview that assesses social, communication, motor, and daily living skills. The Preschool Language Scale-5th Edition (PLS-5) was completed at all visits [21]. This is an interactive, play-based assessment that provides information about receptive and expressive language skills for children birth through age 7 years. Other assessments were performed including the Early Social Communication Scales (ESCS) and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), but results were not available for inclusion in the current analysis. At 12 months of age, assessment for autism risk was performed using the Autism Observation Scale for Infants (AOSI)[22]. The AOSI is a tool that looks at specific behavioral risk markers for ASD. At ages 24 and 36 months, formal assessment for autism using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 (ADOS-2) was performed [23], as well as the Autism Diagnostic Interview- Revised (ADI-R)[24]. The ADOS is a semi-structured, interactive observation tool used to assess for ASD. The ADI-R is a parent interview that focuses on a child’s developmental history, current functioning, social skills, communication and behaviors and interests. The current analysis focuses on assessments through 24 months of age, since the majority of TACERN subjects had not completed the 36-month visit at the time of data cut-off.

2.4 Determination of seizure onset and seizure frequency

A detailed seizure history was obtained from the patients via a seizure diary. Seizure diaries were given to the parent/guardian to record type and frequency of seizures. At enrollment, parents were shown a seizure recognition educational DVD to improve seizure identification and accurate reporting. From the diaries, seizures (i.e. focal, generalized, infantile spasms) were classified by the site neurologist using to ILAE criteria [25]. In the present analysis, seizure onset was defined as the first recorded clinical seizure of any type recorded in the seizure diary. To capture the overall seizure frequency in association with the time of each developmental assessment, the total number of seizures during the six-month period (please see below for further detail regarding data analysis) in between assessments was used to obtain an average number of seizures per month. Because of significant variability among subjects with outliers at the highest end (range 0–981 seizures per month), seizure frequency was also grouped into seizure severity categories for additional analyses as described below): Category 1 (no seizures), Category 2 (1 to 30 seizures, corresponding to an average less than one seizure daily), Category 3 (31 to 60 seizures, corresponding to an average of one seizure daily), and Category 4 (greater than 60 seizures, corresponding to an average of multiple seizures daily). Of note, seizure management at each site was determined by the treating neurologist following best-clinical practices [26].

2.5 Statistical analysis

Assessments performed at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months was used for analysis. An Early Learning Composite standard score from the MSEL was used to determine overall developmental functioning, with a score < 70 used to define developmental delay. In some cases the Early Learning Composite score could not be calculated in lower functioning individuals (14 out of 300 visits). In order to account for lower functioning individuals, MSEL age equivalent scores were converted to developmental quotients (DQ) for each domain (age equivalent/chronological age x 100). An overall composite score then was obtained by taking the average DQs for four subtests (receptive language, expressive language, fine motor, and visual reception). Standard scores from MSEL, VABS, and PLS5 domains and composites were used to examine the relationship between seizures and overall developmental, adaptive, and language functioning respectively. AOSI total scores, ADOS-2 total scores, and ADI-R cutoffs were used at the 24-month visit to define ASD risk for each subject.

The subjects were divided into various groups for the purposes of statistical analyses. The timing of the seizures was examined by dividing the cohort into those who had or did not have a seizure in the six months prior to each developmental testing time point. Other groupings of interest were based on whether or not a subject ever had a seizure or ever had an infantile spasm at any time point prior to when assessment was performed. When comparing two groups with respect to the various performance measures Wilcoxon rank sum and t-tests were performed.

Spearman correlation coefficients were used to examine the relationship between seizure frequency, as defined by one of the four seizure categories described above, and the performance measures. At each of the four time points (6, 12, 18, and 24 months), the correlation between the seizure frequency and the test scores was derived. In addition, the correlation between the seizure frequency at one time point and scores at future time points were also derived, e.g., the correlation between seizure frequency at six months and MSEL score at 12, 18, or 24 months. These correlations will be referred to as lag correlations because the time points are different. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the association, if any, between the four possible ADI-R cutoffs and whether or not the subject ever had epilepsy, whether or not the subject ever had infantile spasms, and the subject’s seizure frequency at 24 months.

The Early Learning Composite on the MSEL, was used as a proxy for developmental delay (score <70, i.e., 2 SD below the mean, indicating significant delay). For each of the time points, a logistic regression model was fit where the response was developmental delay, and the independent variables were age of seizure onset and the presence or absence of a history of infantile spasms. Time points were also combined to perform a repeated measures mixed logistic model with the diagnostic quotient and the composite score described longitudinally. For these models, all quoted means and mean differences are based on the adjusted least squares means and their differences. The standards errors for these means are given with the usual standard error abbreviation (SEM).

Statistical significance was set at an alpha level = 0.05 and p-values were reported without adjustment for multiple comparisons (adjustments for multiple comparison were made using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) and no changes in results were seen). There were occasional missing values within a patient’s visit, but these were so few that there was no need for imputation. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS ® statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Patient Characteristics

One-hundred and thirty-four patients were enrolled in the study. Four patients did not complete any assessments and, therefore, were excluded from the analysis. The average age at the time of enrollment was 5.2 months and at data cut-off was 23.3 months (Table 1). Gender was evenly distributed. A total of 513 developmental assessments were performed. The mean early learning composite score was 94.2 (SD=19.0) at 6 months, 83.1 (SD=20.0) at 12 months, 80.7 (SD=21.85) at 18 months, and 78.3 (SD=22.5) at 24 months. Developmental delay was seen in 7.7% of patients at 6 months, 28.2% at 12 months, 32.9% at 18 months, and 45.5% at 24 months. Ninety-five patients developed epilepsy overall (73.1%), with average age of onset 5.6 ± 3.9 months (range one day to 18.8 months). The most common seizure type encountered was infantile spasms, which were seen in 73 patients (75%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Average Age | |

| Enrollment | 5.2 ± 3.3 months |

| Age at data cut-off | 23.3 ± 10.2 months |

| Sex (M:F) | 68:62 |

| Medication History | Number of Patients at Enrollment (%) |

| Steroids (oral/injection) | 11 (8.5) |

| Vigabatrin | 46 (35.4) |

| More than 1 seizure medication | 28 (21.5) |

| History of Seizures | Cumulative (%) |

| 3 months | 18.5 |

| 6 months | 45.4 |

| 12 months | 66.9 |

| 18 months | 72.3 |

| 24 months | 73.1 |

| Seizure Types | N (%) |

| Infantile spasms | 29 (30) |

| Focal seizures | 21 (22) |

| Infantile spasms + focal seizures | 42 (43) |

| Generalized seizures | 4 (3) |

| Unclassified | 6 (6) |

3.2 Relationship of prior seizures on developmental outcomes and autism-specific behaviors

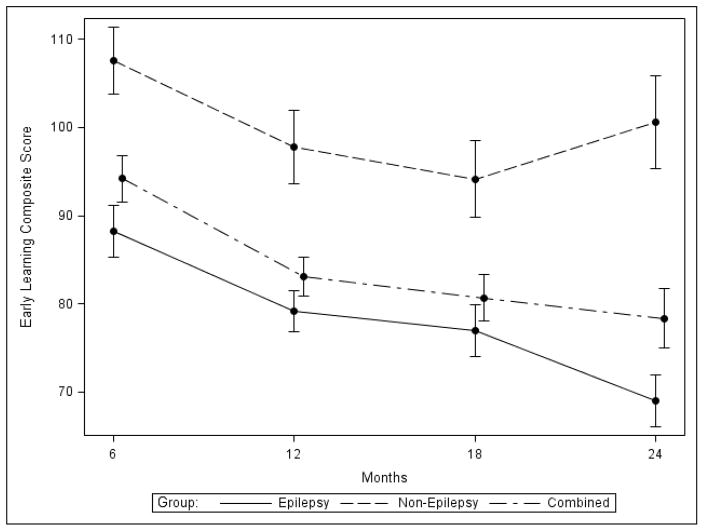

Patients with and without a history of seizures were compared to determine the effect of having any prior seizures relative to time of assessment, on development. As expected, patients without epilepsy performed better than those with epilepsy, and cognition in patients without epilepsy remained stable while those with epilepsy declined over time (Figure 1). When assessed at six months of life, those patients already experiencing seizures performed worse on the MSEL overall (Early Learning Composite score, p<0.001). While nearly all subdomains were significant, visual reception and fine motor were affected to a greater extent than language domains. Significant overall differences also were evident by six months with the VABS (adaptive behavior composite score, p=0.04), driven primarily by motor skills (p<0.01), and PLS-5 (total language standard score, p=0.03), with receptive and expressive domains equally significant. By 12 months, patients exhibited significant differences in all areas (with the exception of the gross motor subdomain on the MSEL that approached significance, p=0.051). Deficiencies persisted through 24 months for areas of the MSEL, VABS, and PLS5 (see Figure 2 for differences in composite scores and supplemental table 1 for additional detail including subdomains).

Figure 1. Relationship between seizure history and overall developmental outcome.

Mullen Scales of Early Learning Early Learning Composite (mean +/− S.D.) is plotted from 6 months to 24 months for all patients (dash/dotted line), those with (solid line) or without (dashed line) prior history of seizures.

Figure 2. Repeated Developmental Assessment in TSC infants and toddlers over time.

Mean +/− S.D. for patients with (red) or without (green) history of seizures prior to assessment point. (A) Mullen Scales of Early Learning Early Learning Composite, (B) Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales Adaptive Behavior Composite, and (C) Preschool Language Scale Total Language Score.

Patients with history of seizures prior to AOSI assessment at 12 months and ADOS-2 at 24 months exhibited more autism-specific behaviors, evidenced by higher total scores on the AOSI (p<0.01) at 12 months and ADOS-2 (p<0.01) at 24 months. On the ADI-R at 24 months, patients with history of seizures were more likely to meet cut-off scores for ASD-associated abnormalities in communication (p=0.03) as compared to patients without any history of seizures. Of note, patients who were seizure-free during the first 12 months of life continued to perform better on subsequent visits compared to patients with seizures. Collectively, these data suggest that 12 months may be an important time point for determining subsequent development and ASD outcome in infants diagnosed with TSC, using history of prior seizures as a key predictor.

Prior studies have implicated infantile spasms as a specific risk factor for developmental delay and ASD in TSC [6, 7, 10]. We, therefore, evaluated the independent relationship between infantile spasms and developmental testing at each time point (Table 2). Interestingly, there was no significant association between developmental performance at six months in those who had already developed infantile spasms, but by 12 months this group did perform significantly worse on the MSEL, VABS, and PLS-5 in overall scores as well as individual subdomains (p<0.01). Significant developmental delays also were evident with each instrument (MSEL, VABS, PLS-5) at 18 and 24 months (p<0.01).

Table 2. Relationship between infantile spasms and developmental outcomes.

Mean and S.D. for each developmental assessment toll (MSEL, VABS, PLS5, AOSI, and/or ADOS) summary or composite score for each time point (6, 12, 18, and 24 months) and subgroup (history of infantile spasms vs. no infantile spasms). *indicates statistically significant difference at the time point between subgroups.

| 6 Months | No Spasms by 6 Months | Spasms within 6 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-value | |

| Early Learning Composite (MSEL) | 95.3 | 19.8 | 91.2 | 16.5 | 0.469 |

| Adaptive Behavior Composite (VABS) | 91.4 | 14.5 | 93.6 | 15.0 | 0.639 |

| Total Language Score (PLS-5) | 99.8 | 18.4 | 94.5 | 16.2 | 0.339 |

| 12 Months | No Spasms by 12 Months | Spasms within 12 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-value | |

| Early Learning Composite (MSEL) | 93.3 | 18.9 | 75.1 | 17.2 | <.0001* |

| Adaptive Behavior Composite (VABS) | 92.8 | 13.2 | 82.3 | 16.7 | 0.001* |

| Total Language Score (PLS-5) | 90.6 | 15.4 | 79.5 | 18.3 | 0.004* |

| AOSI Total Score | 5.5 | 3.5 | 10.7 | 6.9 | <.0001* |

| 18 Months | No Spasms by 18 Months | Spasms within 18 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| VABS | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-value |

| Early Learning Composite (MSEL) | 92.0 | 21.6 | 71.7 | 17.7 | <.0001* |

| Adaptive Behavior Composite (VABS) | 95.7 | 11.5 | 84.1 | 15.9 | 0.0008* |

| Total Language Score (PLS-5) | 97.6 | 16.6 | 81.3 | 21.1 | 0.0005* |

| 24 Months | No Spasms by 24 Months | Spasms within 24 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-value | |

| Early Learning Composite (MSEL) | 94.7 | 20.7 | 67.0 | 15.8 | <.0001* |

| Adaptive Behavior Composite (VABS) | 100.7 | 7.6 | 86.3 | 17.8 | 0.0004* |

| Total Language Score (PLS-5) | 99.4 | 14.1 | 78.6 | 15.9 | <.0001* |

| ADOS Total Score | 5.8 | 6.6 | 11.0 | 8.4 | 0.03* |

The temporal association between ASD risk features and seizures in general and infantile spasms specifically was identical to what was seen for neurocognition. Infantile spasms or any other seizure type with onset before six months was not predictive of later ASD characteristics. However, by 12 months of age, history of spasms became highly significant for the presence of autism risk behaviors on the AOSI (p<0.001) at 12 months and ADOS-2 (p<0.01) at 24 months. Also at 24 months, ADI-R abnormalities correlated with infantile spasms for reciprocal social interaction p=0.02), communication (p=0.02), and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior (p=0.03). Thus as was the case for seizures of all types, infantile spasms occurring before 12 months of age is an important time point for predicting neurodevelopmental and ASD risk in TSC.

3.3 Relationship of seizure frequency on developmental outcomes and autism-specific behaviors

In addition to a history of seizures, higher frequency of seizures in the six months immediately prior to developmental assessment also demonstrate significant impact (Supplemental Table 2). At six months of age, higher seizure frequency correlated with lower scores overall and on each subdomain of the MSEL, particularly in the areas of fine motor and visual reception (p<0.01). On the VABS significant differences were noted in fine motor skills, activities of daily living, and overall composite score (p<0.05). Differences on the PLS5 were seen in total language score, which was primarily driven by differences receptive language (p=0.02). By 12 months, higher seizure frequency correlated with lower scores on all developmental and language testing, which persisted through 24 months. Increased autism behaviors on the AOSI (p<0.01) and ADOS-2 (p<0.01) were also associated with higher seizure frequency at 12 and 24 months, respectively. Seizure frequency did not correlate with ADI-R cut-off scores, though reciprocal social interaction approached significance (p=0.055).

We investigated if more frequent seizures early in life (before 6 months), when greater injury to the rapidly developing brain might occur, have greater negative impact on development assessed at later time points (Table 3). While seizure frequency correlated with lower developmental scores at six months, it did not correlate with outcomes at 24 months in most domains. The only exception found was the VABS Adaptive Behavior Composite. It was not until 12 months that current seizure frequency was predictive of lower MSEL, VABS, and PLS5 scores at 18 and 24 months (p<0.01). Furthermore, the impact of seizure reduction over time (presumably from effective treatment) was disappointing. Reduced seizure frequency at later time points when compared to earlier time points generally did not significantly correlate with improved developmental testing scores. The only exception noted were patients achieving complete seizure control (zero seizures in previous six months rather than a reduction in seizures), where improvement was seen in receptive language scores on MSEL (p=0.02) and communication domain on the VABS (p=0.02) at 12 months compared to six months.

Table 3.

Impact of seizure frequency on current and later developmental outcomes. Seizure frequency was determined at each clinical time point (column 1), which was then correlated with developmental assessments measure at that and each subsequent time point (columns 2, 3, 4, and 5). Shown is the correlation coefficient (r), statistical significance, and N for each analysis. *p<0.05. **p<0.01.

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning- Early Learning Composite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Seizure frequency | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months |

| 6 months | −0.59536 | −0.35951 | −0.3676 | −0.39296 |

| p value | 0.001* | 0.021* | 0.0457* | 0.096 |

| N | 52 | 41 | 30 | 19 |

|

|

||||

| 12 months | −0.47335 | −0.45976 | −0.62064 | |

| p value | 0.0001** | 0.0001** | 0.0001** | |

| N | 84 | 67 | 44 | |

|

|

||||

| 18 months | −0.45446 | −0.59028 | ||

| p value | 0.0001** | 0.0001** | ||

| N | 70 | 44 | ||

|

|

||||

| 24 months | −0.6138 | |||

| p value | 0.0001** | |||

| N | 44 | |||

|

|

||||

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales- Adaptive Behavior Composite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Seizure frequency | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months |

| 6 months | −0.31384 | −0.12083 | −0.23513 | −0.51403 |

| p value | 0.0208* | 0.4346 | 0.211 | 0.0171* |

| N | 54 | 44 | 30 | 21 |

|

|

||||

| 12 months | −0.43386 | −0.37251 | −0.50517 | |

| p value | 0.0001** | 0.0021** | 0.0003** | |

| N | 91 | 66 | 48 | |

|

|

||||

| 18 months | −0.32492 | −0.45686 | ||

| p value | 0.0065* | 0.0011** | ||

| N | 69 | 48 | ||

|

|

||||

| 24 months | −0.35231 | |||

| p value | 0.0141* | |||

| N | 48 | |||

|

|

||||

| Preschool Language Scales-5th edition- Total Language Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Seizure frequency | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months |

| 6 months | −0.3034 | −0.17109 | −0.03877 | −0.39855 |

| p value | 0.0322* | 0.2912 | 0.8359 | 0.1014 |

| N | 50 | 40 | 31 | 18 |

|

|

||||

| 12 months | −0.38189 | −0.39748 | −0.40049 | |

| p value | 0.0003** | 0.0007** | 0.0071* | |

| N | 85 | 69 | 44 | |

|

|

||||

| 18 months | −0.33323 | −0.56745 | ||

| p value | 0.0042** | 0.0001** | ||

| N | 72 | 44 | ||

|

|

||||

| 24 months | −0.40216 | |||

| p value | 0.0068* | |||

| N | 44 | |||

|

|

||||

3.4 Timing of seizure onset is more important than seizure type or seizure frequency for predicting developmental outcome and autism risk

Longitudinal data was used to logistically model changes in development that were specifically attributable to the development of epilepsy in this population. We examined both developmental quotient (DQ) and Early Learning Composite (ELC) of the MSEL separately to compare sensitivity of each measure at early time points and to assess change over time that was directly attributable to coexistent epilepsy. DQ was 10.6 points (SEM=7.0) higher in patients without epilepsy at six months than in those with epilepsy, but not significant (p=0.14). By 12 months, however, this difference grew to 24.4 points (SEM=10.5) and was significant (p=0.02). ELC, in contrast, significant results were found at 6 months (+16.3, SEM=5.9, p<0.01) but not 12 months (+12.1, SEM=7.5, p=0.10). When we examined the difference between patients with and without epilepsy across all four time points (6, 12 ,18, and 24 months) and adjusted for the visit at which epilepsy was diagnosed, both DQ (+32.2, SEM=5.7, p<0.001) and ELC (+32.3, SEM 5.6, p<0.001) continued to demonstrate significant difference between groups at 24 months. Both also demonstrated a widening deficit gap from 12 to 24 months, but only ELC was statistically significant (p<0.01). Collectively, the models demonstrate that although either DQ or ELC can be used to identify and monitor overall developmental delay attributable to epilepsy in TSC infants, ELC appears more sensitive than DQ when infants are younger (6 months) and for assessing changes in developmental trajectory over time when older (12–24 months). However, DQ remained useful to identify developmental delay specifically associated with epilepsy at 12 months of age in this population.

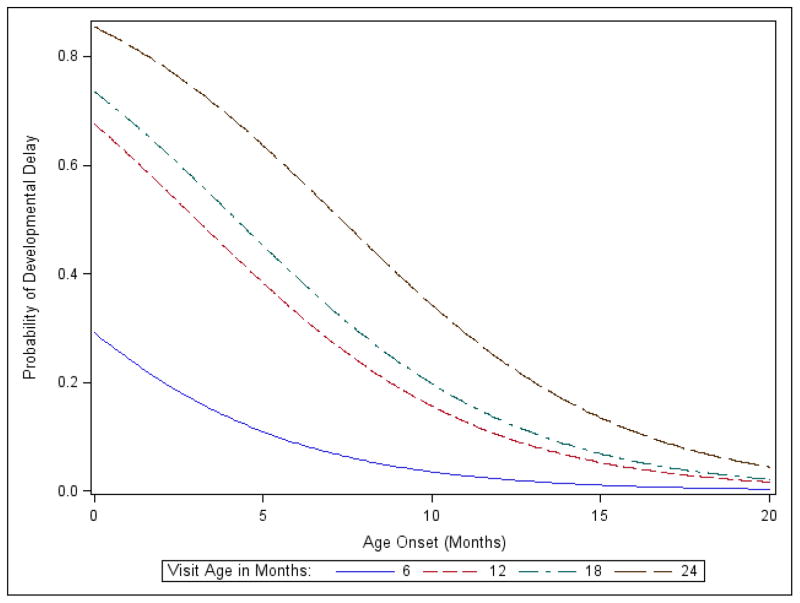

Finally, we used the model to evaluate the individual contributions of infantile spasms, seizure frequency, and age of seizure onset on developmental delay at each time point (Figure 3). In the presence of seizure onset age, seizure frequency and having a history of infantile spasms did not significantly affect developmental test scores. Thus, timing of seizure onset was more important than seizure type and seizure frequency in determining developmental outcome. This effect was not apparent at six and 12 months of age (p=0.23 and 0.19, respectively), but by 18 months of age, the odds ratio was 1.34 (95%CI of 1.07–1.66, p<0.01). At 24 months the odds ratio increased to 1.61, but this result was directional (95%CI of 0.99–2.64, p=0.057) In other words, for each one-month increase in age at seizure onset, the odds of not having developmental delay go up by approximately 34% by 18 months of age and 61% by 24 months of age.

Figure 3. Logistic model predicting likelihood of developmental delay as a function of age of seizure onset.

Each plot shows the probability of developmental delay at each time point of determining risk (6 months, blue; 12 months, red; 18 months, green; and 24 months, black), as a function of age at time of seizure onset.

4. DISCUSSION

This multicenter, prospective study provides further evidence of the integral relationship between seizures and neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with TSC. The negative association between seizure frequency and cognitive functioning has been previously reported in retrospective and case control studies [4, 11]. The only prospective study of similar size and design to date involving infants and toddlers is the TSC2000 study by Bolton et al [6]. In assessing genetic, neurological, and epilepsy-related risk factors for developmental outcome in TSC, they found that higher seizure burden as measured using the Early Childhood Epilepsy Severity Scale (E-CHESS) was associated with worse intellectual outcome. However, seizure data was only collected at three time points and in many cases seizure information was collected retrospectively. Also, intellectual functioning was only measured at one time point. Our prospective study design with standardized developmental assessment battery repeated at scheduled intervals between 3–36 months of age combined with continuous collection of seizure data throughout allows a true repeated assessment of ongoing development and permitted more thorough investigation of the temporal relationship of seizures during this critical period of development. Our data shows that earlier seizure onset along with higher seizure frequency, especially by 12 months of age, negatively affects both immediate and future neurodevelopmental outcomes. In addition, developmental delays can be detected in some patients as early as 6 months, especially in those with higher seizure frequency. These early delays are seen particularly in the nonverbal domains, which is consistent with work performed by Jeste et al [27]. But it was at 12 months in which history of any seizures generally and infantile spasms particularly that were predictive of more global developmental delay and ASD behaviors at later time points. This was especially true when seizures were not 100% controlled, and patients doing well at 12 months very likely were to continue to do well through 24 months of age. Thus it appears that 6–12 months is an important time point for when considering use of interventions to improve seizure control, which in turn would be expected to have corresponding benefit for developmental outcome at 24 months.

While seizure type and seizure frequency are important, we found that earlier onset of seizures is most predictive of developmental outcome, consistent with previous studies [2, 4, 7, 11]. The presence of infantile spasms has a significant impact in determining developmental outcome, but this relationship was secondary to the timing of seizure onset. In other words, although the seizure type most likely to occur at seizure onset in our population was infantile spasms, we found that age at seizure onset exhibited greater impact on predicting developmental outcome. Our finding that timing of seizure onset is more significant than the presence or absence of infantile spasms differs from conclusions drawn by others [2, 10, 11, 15, 28]. For example, Jozwiak et al. found that the presence of infantile spasms was associated with 3–4 times higher risk of moderate to profound delays independent of age of seizure onset [11]. With the overlap between age of seizure onset and infantile spasms, it is only with continuous collection of seizure data and serial developmental assessments in this age range that the specific contribution of each predictor for developmental outcome can be individually appreciated and differentiated. Additional variables may still be important in predicting long-term neurocognitive or neurobehavioral outcomes that were not assessed in our cohort. For example, the TSC2000 study found that TSC genotype, tuber load, and history of status epilepticus also contribute to estimated IQ [6]. Future analysis of our patient population includes determining the impact of type of TSC mutation on developmental outcome. We are also investigating the timing, types and intensity of interventional therapies provided to these infants and their impact on developmental outcomes.

Some developmental domains appeared to improve over time when complete seizure freedom was achieved. However, it was disheartening to find that improved but incomplete seizure control generally did not improve overall developmental outcome at 24 months. This is an important consideration when thinking about treatment options for this young patient population, with the aim for complete elimination of seizures, when possible, for best neurodevelopmental outcome. Bombardieri et al. reported that infants treated with vigabatrin within the first week of seizure onset did better in terms of overall seizure control, and none developed ASD or severe intellectual disability in comparison to patients treated later with vigabatrin and incomplete seizure control [29]. Another study reported similar results in an open-label preventative study using vigabatrin to treat epileptiform discharges prior to first seizure in infants with TSC [30]. Thus early, even preventative, treatment where conditions for complete seizure control are most favorable provides the most desirable and rationale strategy for best long-term cognitive and developmental outcome. Targeting older individuals may miss a critical window when interventions and treatment could be most beneficial.

All of our patients without a history of seizures had typical development, consistent with other studies [3, 11, 31, 32]. Humphrey et al found that patients with infantile spasms had normal development prior to onset of spasms, which dropped into the delayed range after spasm onset, and that this drop in development was significantly lower than in patients who developed other seizure types [33]. These would suggest that seizures cause or at least contribute to onset or progression of neurocognitive and intellectual impairments. However, another study reported intellectual dysfunction in 12% of patients without a history of seizures[2] and several animal models have demonstrated deficits even in the absence of brain malformations or seizures [34, 35], suggesting that neurocognitive impairments, ASD, and other features of TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorder (TAND) are not exclusively dependent on pre-existing or concurrent development of seizures [17]. TSC at the molecular level is caused by lost regulation of mTOR. Various TSC animal models of epilepsy and TAND can be rescued with an mTOR inhibitor, suggesting that lack of mTOR in and of itself is either totally responsible or is a major contributor to neurodevelopmental functioning. Clinically, mTOR treatment has been shown to reduce seizure frequency in medically-refractory TSC patients [36–40]. These same patients have reported improvement in measures of cognition, behavior, and quality of life [36]. By closely investigating the temporal evolution of development at the same time when clinical seizures first emerge, we hoped to determine whether or not seizures directly impact neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes in TSC. The alternative hypothesis is that seizures, neurocognition, and ASD are parallel phenomenon and closely correlated with one another but independent manifestations of mutually underlying aberrant physical CNS development and neuronal connectivity. Ultimately both models may prove true, with seizures acting as a trigger for predisposed aberrant neurodevelopment or providing additive insult that increases the likelihood or severity of deficits. In fact, we found that early seizure onset and worse seizure frequency strongly correlated with poor developmental outcome, suggesting a potentially direct negative effect on the early brain. However, improved seizure control did not significantly improve developmental outcomes, so early onset of seizures also may be predictive of treatment response or there could be a critical period when the developing brain is most vulnerable to the negative impacts of seizures that cannot be easily reversed. Clinical trials are underway to investigate the latter, evaluating if early treatment before the onset of clinical seizures can prevent progression of epileptogenesis and onset of clinical seizures and therefore improve long term developmental outcomes. Additional analysis of the EEG and MRI collected in our cohort is underway that may provide additional insight into this unresolved question that has important mechanistic and clinical implications for disease-modifying and preventative therapies.

CONCLUSIONS

Cognitive deficits and behavioral disorders are common in TSC and can be detected within the first year of life. Past and current seizures are highly predictive of developmental delays in infants and toddlers with TSC, with timing of seizure onset most predictive of future development. Seizure frequency and presence of infantile spasms are also important but have less impact than age at seizure onset. Targeting seizure prevention or control by 12 months of life is likely to provide best opportunity for improving long-term developmental outcome in at-risk patients with TSC.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Infants with TSC who develop seizures early in life are more likely to exhibit global developmental deficits by 24 months of age than infants with TSC without early seizures.

Infantile spasms are most common in this population, occurring alone or in combination with focal seizures.

Infantile spasms, higher seizure frequency, and early age of seizure onset significantly correlate with poorer developmental outcome.

Age of seizure onset has greater impact on developmental outcome by 24 months of age than seizure type or seizure frequency.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the NIH (U01-NS082320, P20-NS080199) and the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance. The study utilized clinical research facilities and resources supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health Grant (UL1-TR000077 and UL1-TR000124).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

JYW serves on the professional advisory board for the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance; has received honoraria from and serves on the scientific advisory board and the speakers’ bureau for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Lundbeck; and has received research support from the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Today’s and Tomorrow’s Children Fund, Department of Defense/Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program, and the NIH (U01NS082320, P20NS080199, R01NS082649, U54NS092090, and U01NS092595).

MS is supported by Developmental Synaptopathies Consortium (U54 NS092090), which is part of the NCATS Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). His lab receives research funding from Roche, Pfizer and he has served on the Scientific Advisory Board of Sage Therapeutics. In addition, he serves on the Professional Advisory Board of the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance and is an Associate Editor of Pediatric Neurology.

DAK has received consulting and speaking fees and travel expenses from Novartis and additional research support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the NIH (U01-NS082320, U54-NS092090, P20-NS080199), the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance, the Van Andel Research Institute, Novartis, and Upsher-Smith Pharmaceuticals. In addition he serves on the professional advisory board and international relations committee for the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance and the editorial board of Pediatric Neurology. DAP has received research support from NIH (U01-NS082320; U54-NS092090; U01-NS092595); research support, consulting fees, and travel reimbursement from Curemark, LLC; and research support from Biomarin and Novartis.

The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Osborne JP, Fryer A, Webb D. Epidemiology of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:125–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu-Shore CJ, Major P, Camposano S, Muzykewicz D, Thiele EA. The natural history of epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1236–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joinson C, O'Callaghan FJ, Osborne JP, Martyn C, Harris T, Bolton PF. Learning disability and epilepsy in an epidemiological sample of individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex. Psychol Med. 2003;33:335–44. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702007092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winterkorn EB, Pulsifer MB, Thiele EA. Cognitive prognosis of patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2007;68:62–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000250330.44291.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curatolo P, Moavero R, de Vries PJ. Neurological and neuropsychiatric aspects of tuberous sclerosis complex. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:733–45. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton PF, Clifford M, Tye C, Maclean C, Humphrey A, le Marechal K, Higgins JN, Neville BG, Rijsdjik F, Yates JR. Intellectual abilities in tuberous sclerosis complex: risk factors and correlates from the Tuberous Sclerosis 2000 Study. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2321–31. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jansen FE, Vincken KL, Algra A, Anbeek P, Braams O, Nellist M, Zonnenberg BA, Jennekens-Schinkel A, van den Ouweland A, Halley D, van Huffelen AC, van Nieuwenhuizen O. Cognitive impairment in tuberous sclerosis complex is a multifactorial condition. Neurology. 2008;70:916–23. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000280579.04974.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolton PF. Neuroepileptic correlates of autistic symptomatology in tuberous sclerosis. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:126–131. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolton PF, Park RJ, Higgins JNP, Griffiths PD, Pickles A. Neuro-epileptic determinants of autism spectrum disorders in tuberous sclerosis complex. Brain. 2002;125:1247–1255. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey A, MacLean C, Ploubidis GB, Granader Y, Clifford M, Haslop M, Neville BG, Yates JR, Bolton PF. Intellectual development before and after the onset of infantile spasms: a controlled prospective longitudinal study in tuberous sclerosis. Epilepsia. 2014;55:108–16. doi: 10.1111/epi.12484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jozwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, Michalowicz R, Chmielik J. Skin lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis complex: their prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:911–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vignoli A, La Briola F, Turner K, Scornavacca G, Chiesa V, Zambrelli E, Piazzini A, Savini MN, Alfano RM, Canevini MP. Epilepsy in TSC: certain etiology does not mean certain prognosis. Epilepsia. 2013;54:2134–42. doi: 10.1111/epi.12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeste S, Sahin M, Bolton P, Ploubidis G, Humphrey A. Characterization of autism in young children with tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:520–525. doi: 10.1177/0883073807309788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Numis AL, Major P, Montenegro MA, Muzykewicz DA, Pulsifer MB, Thiele EA. Identification of risk factors for autism spectrum disorders in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2011;76:981–987. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182104347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vignoli A, La Briola F, Peron A, Turner K, Vannicola C, Saccani M, Magnaghi E, Scornavacca GF, Canevini MP. Autism spectrum disorder in tuberous sclerosis complex: searching for risk markers. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:154. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0371-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaczorowska M, Jurkiewicz E, Domańska-Pakiěa D, Syczewska M, Łojszczyk B, Chmielewski D, Kotulska K, Kuczyński D, Kmieć T, Dunin-Wa̧sowicz D, Kasprzyk-Obara J, JóŸwiak S. Cerebral tuber count and its impact on mental outcome of patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsia. 2011;52:22–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curatolo P, Aronica E, Jansen A, Jansen F, Kotulska K, Lagae L, Moavero R, Jozwiak S. Early onset epileptic encephalopathy or genetically determined encephalopathy with early onset epilepsy? Lessons learned from TSC. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20:203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Northrup H, Krueger DA. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 international tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullen E. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland adaptive behavior scales: Second Edition (Vineland II), survey interview form/caregiver rating form. Livonia, MN: Pearson Assessments; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman I, Steiner V, Pond R. Preschool Language Scale. 5. Pearson; 2011. (PLS-5) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryson SE, Zwaigenbaum L, McDermott C, Rombough V, Brian J. The Autism Observation Scale for Infants: scale development and reliability data. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:731–8. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0440-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Pickles A, Rutter M. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:205–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinnar S. The new ILAE classification. Epilepsia. 2010;51:715–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krueger DA, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 international tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:255–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeste SS, Wu JY, Senturk D, Varcin K, Ko J, McCarthy B, Shimizu C, Dies K, Vogel-Farley V, Sahin M, Nelson CA., 3rd Early developmental trajectories associated with ASD in infants with tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurology. 2014;83:160–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yates JR, Maclean C, Higgins JN, Humphrey A, le Marechal K, Clifford M, Carcani-Rathwell I, Sampson JR, Bolton PF. The Tuberous Sclerosis 2000 Study: presentation, initial assessments and implications for diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1020–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.2011.211995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bombardieri R, Pinci M, Moavero R, Cerminara C, Curatolo P. Early control of seizures improves long–term outcome in children with tuberous sclerosis complex. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2010;14:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.JóŸwiak S, Kotulska K, Domańska-Pakieła D, Łojszczyk B, Syczewska M, Chmielewski D, Dunin-Wsowicz D, Kmieć T, Szymkiewicz-Dangel J, Kornacka M, Kawalec, Kuczyński D, Borkowska J, Tomaszek K, Jurkiewicz E, Respondek-Liberska M. Antiepileptic treatment before the onset of seizures reduces epilepsy severity and risk of mental retardation in infants with tuberous sclerosis complex. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2011;15:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomez MR. Criteria for diagnosis. 2. Raven; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shepherd CW, Gomez MR, Lie JT, Crowson CS. Causes of death in patients with tuberous sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:792–6. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humphrey A, Williams J, Pinto E, Bolton PF. A prospective longitudinal study of early cognitive development in tuberous sclerosis - a clinic based study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13:159–65. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-0383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goorden SM, van Woerden GM, van der Weerd L, Cheadle JP, Elgersma Y. Cognitive deficits in Tsc1+/− mice in the absence of cerebral lesions and seizures. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:648–55. doi: 10.1002/ana.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehninger D, Han S, Shilyansky C, Zhou Y, Li W, Kwiatkowski DJ, Ramesh V, Silva AJ. Reversal of learning deficits in a Tsc2+/− mouse model of tuberous sclerosis. Nature Medicine. 2008;14:843–848. doi: 10.1038/nm1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krueger DA, Wilfong AA, Holland-Bouley K, Anderson AE, Agricola K, Tudor C, Mays M, Lopez CM, Kim MO, Franz DN. Everolimus treatment of refractory epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann Neurol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ana.23960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, Agricola K, Tudor C, Mangeshkar P, Wilson KA, Byars A, Sahmoud T, Franz DN. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:1801–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franz DN, Agricola K, Mays M, Tudor C, Care MM, Holland-Bouley K, Berkowitz N, Miao S, Peyrard S, Krueger DA. Everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: 5-year final analysis. Ann Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1002/ana.24523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.French JA, Lawson JA, Yapici Z, Ikeda H, Polster T, Nabbout R, Curatolo P, de Vries PJ, Dlugos DJ, Berkowitz N, Voi M, Peyrard S, Pelov D, Franz DN. Adjunctive everolimus therapy for treatment-resistant focal-onset seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis (EXIST-3): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2016;388:2153–2163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krueger DA, Wilfong AA, Talley CM, Mays M, Agricola K, Tudor C, Capal J, Holland-Bouley K, Franz DN. Long-term treatment of epilepsy with eveorlimus in tuberous sclerosis. Neurology. 2016;87:2408–15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.