Abstract

In their commentary, Sauter et al. claim that we (Gendron, Roberson, van der Vyver & Barrett, 2014) failed to replicate their findings of universal emotion perception, originally published in the Proceedings of the National Academy (Sauter, Eisner, Ekman, & Scott, 2010), because we (1) included non-universal positive emotion categories in our analysis and (2) did not use rigorous manipulation checks. We show that (1) we fail to find universal emotion perception even for negative emotion categories and (2) the manipulation checks that Sauter et al. now elaborate on in their commentary likely taught Himba participants the Western emotion categories needed to produce the performance they observed. We conclude that free-labeling experiments (such as the one we used in Gendron et al., 2014, Study 1) provide a better test of cross-cultural emotion perception.

We recently published two experiments showing that emotions were not universally perceived in vocalizations. We traveled to remote locations in Namibia and sampled participants from the Himba cultural group. Participants in Experiment 1 listened to vocalizations and freely labeled them. Participants in Experiment 2 followed a forced-choice procedure similar to that published by Sauter, Eisener, Ekman and Scott (2010) where they had to choose which of two vocalizations (a target and a foil) matched brief emotional stories (embedded with emotion words). Refining Sauter et al.’s (2010) finding that Himba perceivers had above-chance performance in choosing vocalizations to match story/word cues, we observed that Himba individuals correctly perceived vocalizations according to their positivity or negativity (i.e., valence), but not in terms of presumed universal emotion categories (e.g., anger or fear) (Gendron, Roberson, van der Vyver, & Barrett, 2014a). Our finding replicated our free labeling study (Experiment 1), as well as other data showing that Himba participants perceive valence, but not Western discrete emotion categories, in posed facial expressions (Gendron et al., 2014b). In their commentary, Sauter and co-authors (2014) re-analyzed their data to rule out valence as an alternative explanation for their findings supporting universal emotion perception and suggested two reasons why we did not replicate their findings. We appreciate the opportunity to respond, and offer three suggestions of our own that question the conclusions and details of the experimental method that Sauter and co-authors now elaborate on.

1. Positive emotion categories do not obscure evidence of universality

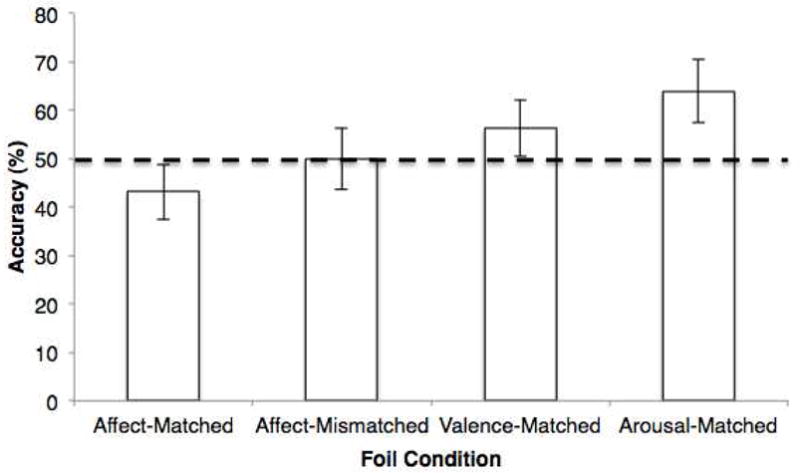

Sauter et al. claim that by including stimuli for pride, pleasure, and relief in our analysis,1 we obscured evidence for universal emotion perception. Here we present the results for only the negative emotion categories (Figure 1). Himba participants chose the correct vocalization only when the target and the foil differed by valence (above-chance performance only for arousal-matched trials that rely on valence perception; t(36)= 2.136, p<.02, 1-tailed). This is exactly the pattern that we found in our original results when all the data were included (Gendron et al., 2014, Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Mean percent accuracy (+/− SEM) of participants for negative emotion targets only, across four task conditions.

2. In cross-cultural research, where is the boundary between manipulation checks and category learning?

In their original manuscript, Sauter et al. (2010) state that following the emotion scenario cue “the participant was asked how the person was feeling” (p. 2411) to confirm “they had understood the intended emotion of the story” (p. 2408). In their commentary, Sauter and co-authors (2014) further elaborate: “each participant was asked, after each story, how the target person was feeling, in order to ensure that they had understood the story correctly” and “participants could listen several times to the recorded story until they could explain the intended emotion in their own words. The inclusion of a rigorous manipulation check with experimenter verification rather than relying on participants’ reports, was thus crucial” (Sauter et al 2014, p. xx, italics added). Sauter et al. appear to be saying that they did not allow Himba participants to proceed to the main experiment until they could categorize (and/or elaborate on) the emotion stories consistently with a Western cultural expectation. The “rigorous” manipulation check that Sauter et al. now describe likely encouraged category learning for Himba participants before they were allowed to complete experimental trials.

Sauter et al. (2014) further suggest that our failure to similarly probe our subjects is responsible for our failure to replicate their findings of universal emotion perception. If Sauter et al are saying, in effect, that we did not teach our Himba participants the Western emotion categories before we did the experiment, and thus we did not observe universal emotion perception, then they are right. We did not provide any guidance to participants to ensure that participants understood the emotion stories in a Western way; participants listened to the emotion story until they indicated they understood it (i.e., from their cultural perspective). We did not ask participants to describe the scenarios (or have an experimenter verify content) as this check defeats the purpose of the experiment. If you have to allow for, or even inadvertently guide Himba participants to learn Western before they can perform the perception task, then these emotions probably aren’t all that universal.

3. As a method for studying cultural variation in emotion perception, forced-choice is confirmatory-oriented, whereas free-labeling is discovery-oriented

The forced-choice response format used by Sauter et al. (2010), in our Experiment 2, and favored by those who study emotion perception constrains participants’ response options, thus limiting the ability to discover cross-cultural variation (cf. Russell, 1994).2 Emotion word stimuli/response options can prime embodied concept knowledge (e.g., Lebois, Wilson-Mendenhall & Barsalou, in press; Trumpp, Traub, Pulvermüller, & Kiefer, 2014) and lead to selection of inappropriate or nonsensical responses (Russell, 1993; Nelson, 2011; see Nelson & Russell, 2013). Free labeling procedures come closer to assessing what participants spontaneously perceive (Widen & Russell, 2002), allowing a more ecologically valid assessment of emotion perception (e.g., capturing variation in complexity and cultural specificity of word use). We found spontaneous responses revealed unexpected variation in emotion perception processes of mentalizing and action-identification (Gendron et al., 2014a, b); Individuals in the Himba culture do not use emotion words as spontaneously or frequently as their Western counterparts. Moreover, participants from Western cultures often fail to produce the expected “universal” pattern of emotion perception when free-labeling (for review, see Nelson & Russell, 2013).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institutes of Health Director’s Pioneer Award (DP1OD003312) to Lisa Feldman Barrett.

Footnotes

Other researchers have proposed that pride (Tracy & Robbins, 2008), pleasure and relief (e.g., Ekman & Cordaro, 2011) are good candidates for universal emotional categories.

The majority of forced-choice methods present participants with stimuli (faces, vocalizations, or body postures) and stipulate that participants use Western emotion words or their translations to perceive the presented stimuli.

Author contributions

M.G. re-analyzed the data, M.G. and L.F.B. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the original study design and writing of the manuscript.

References

- Ekman P, Cordaro D. What is meant by calling emotions basic. Emotion Review. 2011;3(4):364–370. [Google Scholar]

- Gendron M, Roberson D, van der Vyver JM, Barrett LF. Cultural Relativity in Perceiving Emotion From Vocalizations. Psychological science. 2014a;25(4):911–920. doi: 10.1177/0956797613517239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron M, Roberson D, van der Vyver JM, Barrett LF. Perceptions of emotion from facial expressions are not culturally universal: Evidence from a remote culture. Emotion. 2014b;14(2):251. doi: 10.1037/a0036052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebois LA, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Barsalou LW. Are automatic conceptual cores the gold standard of semantic processing? The context-dependence of spatial meaning in grounded congruency effects. Cognitive science. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12174. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson NL. A facial expression of pax: Revisiting preschoolers’ “Recognition of expressions”. Boston College; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson NL, Russell JA. Universality revisited. Emotion Review. 2013;5(1):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. Forced-choice response format in the study of facial expression. Motivation and Emotion. 1993;17:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expressions? A review of the cross-cultural studies. Psychological bulletin. 1994;115(1):102. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter DA, Eisner F, Ekman P, Scott SK. Cross-cultural recognition of basic emotions through nonverbal emotional vocalizations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(6):2408–2412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908239106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy JL, Robins RW. The nonverbal expression of pride: evidence for cross-cultural recognition. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2008;94(3):516. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumpp NM, Traub F, Pulvermüller F, Kiefer M. Unconscious automatic brain activation of acoustic and action-related conceptual features during masked repetition priming. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2014;26(2):352–364. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]