Abstract

Hyperoxia contributes to the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a chronic lung disease of human infants that is characterized by disrupted lung angiogenesis. Adrenomedullin (AM) is a multifunctional peptide with angiogenic and vasoprotective properties. AM signals via its cognate receptors, calcitonin receptor-like receptor (Calcrl) and receptor activity-modifying protein 2 (RAMP2). Whether hyperoxia affects the pulmonary AM signaling pathway in neonatal mice and whether AM promotes lung angiogenesis in human infants are unknown. Therefore, we tested the following hypotheses: (1) hyperoxia exposure will disrupt AM signaling during the lung development period in neonatal mice; and (2) AM will promote angiogenesis in fetal human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs) via extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1/2 activation. We initially determined AM, Calcrl, and RAMP2 mRNA levels in mouse lungs on postnatal days (PND) 3, 7, 14, and 28. Next we determined the mRNA expression of these genes in neonatal mice exposed to hyperoxia (70% O2) for up to 14 d. Finally, using HPAECs, we evaluated if AM activates ERK1/2 and promotes tubule formation and cell migration. Lung AM, Calcrl, and RAMP2 mRNA expression increased from PND 3 and peaked at PND 14, a time period during which lung development occurs in mice. Interestingly, hyperoxia exposure blunted this peak expression in neonatal mice. In HPAECs, AM activated ERK1/2 and promoted tubule formation and cell migration. These findings support our hypotheses, emphasizing that AM signaling axis is a potential therapeutic target for human infants with BPD.

Keywords: Adrenomedullin, Calcitonin receptor-like receptor, Receptor activity-modifying protein 2, Hyperoxia, Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Introduction

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a chronic lung disease of premature infants that results from an imbalance between lung injury and repair in the developing lung [1]. Despite improved respiratory care management of premature infants, BPD remains the most common morbidity in these infants [2]. In addition, BPD increases the economic burden with an estimated cost of $2.4 billion per year in United States, making it the second most expensive childhood disease after asthma. Thus, there is a need for improved therapies to prevent and/or treat BPD in human infants. Lung blood vessels play a crucial role in lung health. Disrupted lung angiogenesis is a hallmark of developmental lung disorders such as BPD [3]. Lung angiogenesis actively contributes to alveolarization (lung development), and disruption of angiogenesis in the developing lungs causes arrested alveolarization [4]. Thus, understanding the mechanisms that promote the development and function of the lung vascular system is vital to prevent and treat this disease in human infants.

Supplemental oxygen is frequently used as a life-saving therapy in human infants with hypoxic respiratory failure; however, excessive oxygen exposure or hyperoxia leads to BPD. In alignment with other studies [5, 6], we recently demonstrated that hyperoxia-induced lung parenchymal and vascular injury in newborn mice leads to a phenotype that is similar to human BPD [7]. So, we used this model to investigate whether AM signaling is disrupted in experimental BPD.

Adrenomedullin (AM) is a 52-amino acid peptide that is particularly enriched in highly vascularized organs, including lungs, heart, kidneys, and adrenal glands [8]. AM signaling occurs by the functional receptor combination of calcitonin receptor-like receptor (Calcrl) with receptor activity-modifying protein (RAMP)-2 and -3 [9]. AM plays a crucial role in endothelial cell growth and survival [10–12], mainly via extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1/2 pathway [13, 14]. AM−/− mice die in utero due to vascular endothelial disruption [13, 15, 16]. Calcrl−/− and RAMP2−/− mice have a phenotype identical to that of AM−/− mice [13, 15, 17], whereas RAMP3−/− mice survive with few phenotypic defects [18]. These data demonstrate that AM, Calcrl, and RAMP2 genes are critical for vascular development; therefore, our studies focused on these genes.

AM is shown to regenerate alveoli and vasculature in a pulmonary emphysema mouse model [19]. However, several factors remain poorly understood, including: (1) the ontogeny of pulmonary AM, Calcrl, and RAMP2 in mice; (2) the effects of hyperoxia on the AM signaling axis in the developing lungs of mice; and (3) the effects of AM on lung angiogenesis in human preterm infants. Therefore, using neonatal C57BL/6J wild type (WT) and fetal human lung cells, we tested the following hypotheses: (1) hyperoxia exposure will disrupt AM signaling during the alveolarization period in neonatal mice; and (2) AM will promote angiogenesis of fetal human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs) via activation of ERK1/2 pathway.

Materials and Methods

In Vivo Experiments

Animals

This study was approved and conducted in strict accordance with the federal guidelines for the humane care and use of laboratory animals by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Baylor College of Medicine. The C57BL/6J wild type (WT) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Timed-pregnant mice raised in our animal facility were used for the experiments.

Analyses of AM signaling pathway

The lungs were harvested from both male and female mice on postnatal days (PND) 3, 7, 14, and 28 (n=9/time point) for gene expression analyses. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed with 7900HT Real-Time PCR System using TaqMan gene expression master mix (Grand Island, NY; 4369016) and TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) for the following genes: AM, RAMP2, Calcrl, and GAPDH.

Hyperoxia Exposure

Within 24 h of birth, male and female pups were exposed to normoxia (21% O2, n=36) or hyperoxia (70% O2, n=36) for up to 14 d. The dams were rotated between normoxia- and hyperoxia-exposed litters every 48 h to prevent oxygen toxicity in the dams [7]. Following hyperoxia exposure, mice were allowed to recover in air for 14 d as described previously [20]. The lung tissues were harvested on PND 3, 7, and 14 (n=9/time point/exposure) for the analyses of the AM signaling pathway. Additionally, the lung tissues were harvested for lung morphometry and immunohistochemistry on PND 28 (n=9/exposure).

Alveolar and pulmonary vascular morphometry

Alveolar development on selected mice was evaluated by radial alveolar counts (RAC) and mean linear intercepts (MLI) [7]. Pulmonary vessel density was determined based on immunohistochemical staining for von Willebrand factor (vWF), which is an endothelial specific marker. At least 10 counts from 10 random non overlapping fields (20x magnification) was performed for each animal (n=9/ exposure group).

In Vitro Experiments

Cell culture and treatment

The fetal human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs) were obtained from ScienCell research laboratories (San Diego, CA; 3100) and grown according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were treated with various concentrations (0.1 – 1000 nM) of AM for 15 min, after which whole-cell protein was harvested to determine if AM phosphorylates ERK1/2. For tubule formation and scratch assays, cells were treated with 10 nM AM.

Western Blot Assays

Whole-cell protein extracts were obtained by using radio immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer system (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-24948) and subjected to western blotting with the following antibodies: β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; sc-47778, dilution 1:1000), total ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; 4695, dilution 1:1000), and phospho-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling; 9106, dilution 1:1000) antibodies.

Tubule formation and scratch assays

Matrigel and scratch assays were used to determine tubule formation and cell migration, respectively [21, 22]. Briefly, HPAECs grown in reduced serum medium were harvested for the assays. The cells were pretreated with AM and loaded on top of growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Bioscience). Following an incubation period of 18 h, tubule formation was quantified. For the scratch assay, the cells were wounded with a pipette tip before they were treated with AM. The wound closure or cell migration area was estimated using Image J software by comparing the wounded areas at 0 h and 16 h.

Statistical Analyses

The results were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 5 software. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. In vivo experiments: At least three separate experiments were performed for each measurement (n = total animals from the 3 experiments). The effects of age and exposure for the outcome variables (AM, Calcrl, and RAMP2) were assessed using ANOVA, whereas the effect of exposure on lung development was assessed by t-test. In vitro experiments: At least three separate experiments were performed for each measurement. The dose dependent effects of AM on ERK1/2 phosphorylation were assessed by ANOVA, whereas the effects of AM on angiogenesis were assessed by t-test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results and Discussion

The present study demonstrates that AM and its signaling receptors, Calcrl and RAMP2, are increasingly expressed during lung development in mice and exposure of neonatal mice to hyperoxia disrupts the AM signaling pathway in the lungs of these animals. Further, our study demonstrates that AM activates ERK1/2 pathway and promotes angiogenesis in fetal HPAECs.

Lung angiogenesis actively contributes to alveologenesis during development and healthy lung blood vessels are necessary to maintain structural and functional integrity of alveolar structures later in life. Recently, AM signaling is increasingly been recognized as a necessary pathway for vascular remodeling and immune response in physiological states such as pregnancy [23], and disrupted AM signaling is shown to contribute to several pathophysiological states such as preeclampsia [24], systemic and pulmonary hypertension [25, 26], myocardial infarction [27], tumors [28], and lymphedema [29]. Further, Calcrl-RAMP complexes are being explored as important drug targets to treat acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary hypertension, migraine headache, cancer, and several other disorders [30–32], indicating that AM signaling axis can be targeted to develop therapies. However, the effects of hyperoxia on the AM signaling axis in the developing lungs is poorly understood. Additionally, whether AM modulates lung angiogenesis in human infants is unknown. Our studies were designed to address these knowledge gaps.

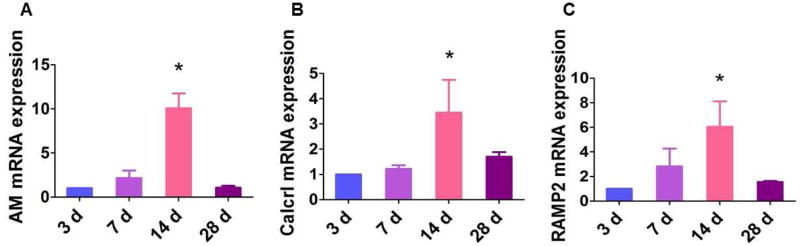

Initially we determined the developmental profile of AM and its receptor components in the lungs of neonatal and adolescent mice by real-time RT-PCR analyses. The mRNA levels of AM (Fig. 1A), Calcrl (Fig. 1B), and RAMP2 (Fig. 1C) progressively increased from PND 3 and peaked on PND 14, before decreasing to the baseline levels on PND 28. Interestingly, the peak expression of AM and its signaling receptors occurred in the time period during which alveolarization occurs in mice. Ramos and colleagues demonstrated a similar finding in the developing human fetal lung [33]. In the lungs, AM and its receptors are co-expressed mainly in endothelial cells and epithelial cells of the airway and alveoli [34–36], suggesting that the effects of AM occur via autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Increased expression of AM signaling components in the cells that modulate proliferation and differentiation combined with increased AM expression during the alveolarization period indicate that there is a mechanistic link between AM signaling and lung development.

Figure 1. Ontogeny of AM and its signaling receptors in mouse lungs.

The lung tissues of air-breathing (normoxia) mice were extracted on postnatal days (PND) 3, 7, 14, and 28, after which RNA was extracted for real-time RT-PCR analysis of AM (A), Calcrl (B), and RAMP2 (C) mRNA expression. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n=3/time point). Significant difference compared to 3-d-old mice is indicated by *, p < 0.05 (ANOVA).

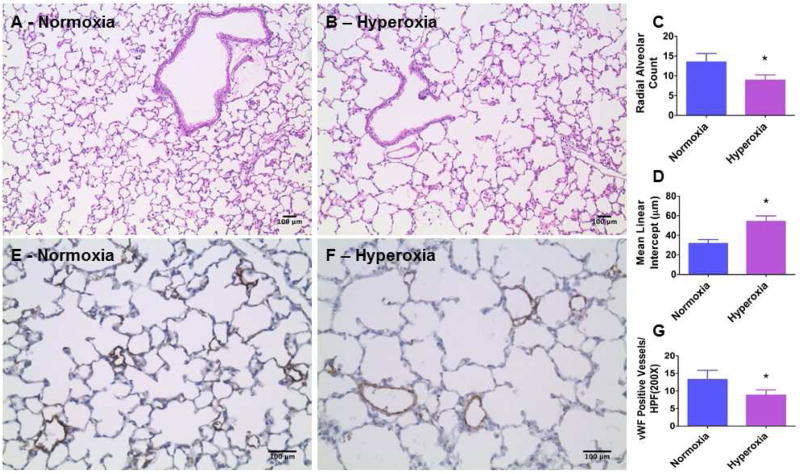

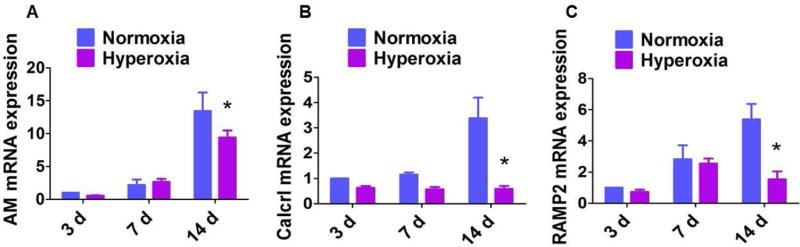

We demonstrated that our mouse model of hyperoxia-induced lung injury meets the requirements needed to model BPD with pulmonary hypertension (PH) experimentally [7]. In that study, we observed that hyperoxia exposure disrupted lung development in mice at PND 14. However, human preterm infants with BPD have anatomical and functional lung abnormalities that persist into adolescence. Therefore, we exposed one-day-old WT mice to normoxia (21% O2) or hyperoxia (70% O2) for 14 d. Hyperoxia-exposed mice were allowed to recover in air for 14 d [20]. Following this recovery period, alveolarization and pulmonary vascularization were determined on PND 28. Hyperoxia-exposed mice continued to have significant decreases in RAC (Figs. 2A–C) and increases in MLI (Figs. 2A,B, and D) indicating that their alveoli were fewer in number and larger in diameter, respectively, when compared with normoxia-exposed mice. Further, hyperoxia-induced decrease in vWF stained lung blood vessels (Figs. 2E–G) persisted following the recovery period. These findings indicate that neonatal mice with hyperoxia-induced lung injury have interrupted lung development that persist to adolescence (PND 28). Our mouse model thus recapitulates the long-term lung morbidity seen in human infants with BPD, making our data clinically relevant. Therefore, we used this mouse model to interrogate the effects of hyperoxia on the AM signaling axis in the developing lungs. Interestingly, hyperoxia exposure in neonatal mice attenuated the increase in AM (Fig. 3A), Calcrl (Fig. 3B), and RAMP2 (Fig. 3C) mRNA expression during the alveolarization period, indicating that AM signaling plays a mechanistic role in hyperoxia-induced developmental lung injury. Our findings are contradictory to those of Vadivel and colleagues, who showed that hyperoxia exposure increased the pulmonary AM expression in neonatal rats [37]. This discrepancy may be due to differences in animal species and the oxygen concentration used for the experiments. However, they demonstrated that the increase in AM expression was a compensatory rather than a contributory response to hyperoxic injury because AM treatment attenuated the lung injury in their experimental animals, a finding which signifies the protective effects of AM against hyperoxic injury. Future studies with AM transgenic mice are needed to determine if AM signaling is both necessary and sufficient to protect against hyperoxia-induced developmental lung injury.

Figure 2. Quantification of alveolarization and pulmonary vascularization on postnatal day 28.

A–B. Representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections, C. Radial alveolar count, D. Mean linear intercepts, E–F. Representative vWF stained lung blood vessels, and G. Quantitative analysis of vWF-stained lung blood vessels per high power field (HPF) of neonatal WT mice that were exposed to normoxia (air) or hyperoxia (70 % O2) for 14 d and allowed to recover in air for 14 d. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n=3/exposure group). Significant differences between normoxiaand hyperoxia-exposed mice are indicated by *, p < 0.05 (t-test). Scale bar = 100 µM.

Figure 3. Expression of AM and its signaling receptors in neonatal mouse lungs exposed to hyperoxia.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of AM (A), Calcrl (B), and RAMP2 (C) mRNA expression in the lungs of neonatal WT mice exposed to normoxia (air) or hyperoxia (70% O2) for up to 14 d. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n=3/time point/exposure group). Significant difference between normoxia- and hyperoxia-exposed mice is indicated by *, p < 0.05 (ANOVA).

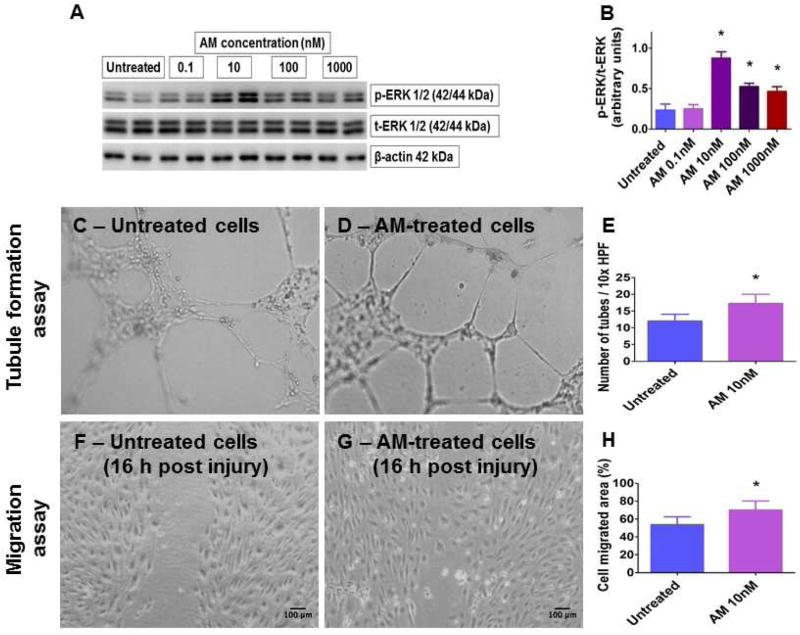

To examine the clinical significance of our animal studies, we investigated the effects of AM treatment in fetal HPAECs. HPAECs were selected because: (1) their proliferation and maturation are crucial for alveolarization and lung growth; (2) their dysfunction contributes to BPD pathogenesis; and (3) AM and its signaling receptors are highly enriched in arterial endothelial cells. ERK1/2 primarily mediates proliferation and differentiation in many cell types [38] and regulate lung morphogenesis in rats [39]. Further, AM signaling induces proliferation and promotes growth and survival of endothelial cells, mainly via ERK1/2 pathway [13, 14, 40]. Hence, we treated HPAECs with various concentrations of AM for 15 min, after which we determined if AM phosphorylates ERK1/2. The treatment time was based on studies showing that AM-induced phosphorylation of this protein peaks 15 min after treatment [13]. AM-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was pronounced when treated with 10 nM AM (Figs. 4A–B), a finding that is consistent with the above mentioned studies. Consequently, 10 nM AM was used to examine if AM promotes lung angiogenesis in human infants. AM-treated fetal HPAECs were subjected to Matrigel [21] and scratch [22] assays to determine tubule formation and cell migration, respectively. AM increased HPAEC tubule formation (Figs. 4C–E) and migration (Figs. 4F–H). Our results are in agreement with the pro-angiogenic properties of AM observed in other endothelial cell types [11–13, 41, 42]. While the observed beneficial effects of AM are seen at concentration that is 10-fold higher than its normal plasma levels, it is possible that the normal cell-specific AM concentration could be possibly much higher than its plasma concentration. Our findings in HPAECs complement our previous study, which showed that AM is necessary to protect human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells against hyperoxic injury [43]. These findings indicate that AM signaling does play a pivotal role in the lung angiogenesis and development in human preterm infants.

Figure 4. Expression of phosphorylated (p) ERK1/2 and quantification of angiogenesis in AM-treated fetal HPAECs.

Primary fetal HPAECs were treated with 0.1, 10, 100, or 1000 nM AM for 15 min, following which whole-cell protein was extracted to determine p- and total (t)-ERK1/2 protein expression (A) by immunoblotting. p-ERK1/2 band intensities were quantified and normalized to t-ERK1/2 band intensities (B). Representative photographs showing tubule formation in growth factor-reduced Matrigel (C–D) and cell migration (F–G), and quantitative analyses of tubule formation (E) and cell migration (H) in HPAECs treated with 10 nM AM. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Values are presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences between untreated- and AM-treated cells are indicated by *, p < 0.05 (ANOVA (p-ERK1/2), t-test (tubule formation and scratch assays)). Scale bar = 100 µM.

In summary, our data suggests that hyperoxia exposure disrupts lung AM signaling in a clinically relevant neonatal mouse model of experimental BPD. Further, our in vitro experiments with fetal human lung cells indicate that AM promotes HPAEC tubule formation and migration mostly via ERK1/2, thereby adding a clinical significance to our in vivo experiments in neonatal mice. Interrupted lung angiogenesis is a major risk factor for BPD and our study suggests that AM has the potential to promote lung angiogenesis; therefore, we propose that AM signaling axis is a potential target to develop meaningful therapies for BPD in human infants.

Highlights.

We studied the ontogeny of adrenomedullin (AM) signaling in mouse lungs.

Expression of AM and its receptors peak during lung development in mice.

Hyperoxia downregulates the expression of AM and its receptors in mouse lungs.

AM activates ERK1/2 in human fetal pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAEC).

AM promotes HPAEC migration and tubule formation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) HD-073323, American Heart Association BGIA-20190008, and American Lung Association RG-349917 to B.S., and by the DDC Core at Baylor College of Medicine with funding from the NIH (P30DK056338). We thank Pamela Parsons for her timely processing of histopathology and immunohistochemistry slides.

Abbreviations

- AM

adrenomedullin

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Calcrl

calcitonin receptor-like receptor

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- HPAECs

human pulmonary artery endothelial cells

- MLI

mean linear intercepts

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PND

postnatal day

- RAC

radial alveolar counts

- RAMP

receptor activity-modifying protein

- WT

wild type

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Jobe AH. Animal Models, Learning Lessons to Prevent and Treat Neonatal Chronic Lung Disease. Frontiers in medicine. 2015;2:49. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Stark AR, Bauer CR, Donovan EF, Korones SB, Laptook AR, Lemons JA, Oh W, Papile LA, Shankaran S, Stevenson DK, Tyson JE, Poole WK. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:147, e141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt AJ, Pryhuber GS, Huyck H, Watkins RH, Metlay LA, Maniscalco WM. Disrupted pulmonary vasculature and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor, Flt-1, and TIE-2 in human infants dying with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2001;164:1971–1980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2101140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thebaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175:978–985. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1660PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aslam M, Baveja R, Liang OD, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Lee C, Mitsialis SA, Kourembanas S. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate lung injury in a murine model of neonatal chronic lung disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0242OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee KJ, Berkelhamer SK, Kim GA, Taylor JM, O'Shea KM, Steinhorn RH, Farrow KN. Disrupted Pulmonary Artery cGMP Signaling in Mice with Hyperoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0118OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds CL, Zhang S, Shrestha AK, Barrios R, Shivanna B. Phenotypic assessment of pulmonary hypertension using high-resolution echocardiography is feasible in neonatal mice with experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia and pulmonary hypertension: a step toward preventing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2016;11:1597–1605. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S109510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinson JP, Kapas S, Smith DM. Adrenomedullin, a multifunctional regulatory peptide. Endocrine reviews. 2000;21:138–167. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLatchie LM, Fraser NJ, Main MJ, Wise A, Brown J, Thompson N, Solari R, Lee MG, Foord SM. RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor. Nature. 1998;393:333–339. doi: 10.1038/30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Sauze S, Delfino C, Mabrouk K, Dussert C, Chinot O, Martin PM, Grisoli F, Ouafik L, Boudouresque F. Effects of adrenomedullin on endothelial cells in the multistep process of angiogenesis: involvement of CRLR/RAMP2 and CRLR/RAMP3 receptors. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2004;108:797–804. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato H, Shichiri M, Marumo F, Hirata Y. Adrenomedullin as an autocrine/paracrine apoptosis survival factor for rat endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2615–2620. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.6.5197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou M, Simms HH, Wang P. Adrenomedullin and adrenomedullin binding protein-1 attenuate vascular endothelial cell apoptosis in sepsis. Annals of surgery. 2004;240:321–330. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133253.45591.5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritz-Six KL, Dunworth WP, Li M, Caron KM. Adrenomedullin signaling is necessary for murine lymphatic vascular development. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:40–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI33302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen P, Huang Y, Bong R, Ding Y, Song N, Wang X, Song X, Luo Y. Tumor-associated macrophages promote angiogenesis and melanoma growth via adrenomedullin in a paracrine and autocrine manner. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:7230–7239. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caron KM, Smithies O. Extreme hydrops fetalis and cardiovascular abnormalities in mice lacking a functional Adrenomedullin gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:615–619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021548898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shindo T, Kurihara Y, Nishimatsu H, Moriyama N, Kakoki M, Wang Y, Imai Y, Ebihara A, Kuwaki T, Ju KH, Minamino N, Kangawa K, Ishikawa T, Fukuda M, Akimoto Y, Kawakami H, Imai T, Morita H, Yazaki Y, Nagai R, Hirata Y, Kurihara H. Vascular abnormalities and elevated blood pressure in mice lacking adrenomedullin gene. Circulation. 2001;104:1964–1971. doi: 10.1161/hc4101.097111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dackor RT, Fritz-Six K, Dunworth WP, Gibbons CL, Smithies O, Caron KM. Hydrops fetalis, cardiovascular defects, and embryonic lethality in mice lacking the calcitonin receptor-like receptor gene. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:2511–2518. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2511-2518.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dackor R, Fritz-Six K, Smithies O, Caron K. Receptor activity-modifying proteins 2 and 3 have distinct physiological functions from embryogenesis to old age. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:18094–18099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami S, Nagaya N, Itoh T, Iwase T, Fujisato T, Nishioka K, Hamada K, Kangawa K, Kimura H. Adrenomedullin regenerates alveoli and vasculature in elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema in mice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;172:581–589. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1280OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velten M, Heyob KM, Rogers LK, Welty SE. Deficits in lung alveolarization and function after systemic maternal inflammation and neonatal hyperoxia exposure. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda Md 1985) 2010;108:1347–1356. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01392.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnaoutova I, Kleinman HK. In vitro angiogenesis: endothelial cell tube formation on gelled basement membrane extract. Nature protocols. 2010;5:628–635. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nature protocols. 2007;2:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matson BC, Caron KM. Adrenomedullin and endocrine control of immune cells during pregnancy. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2014;11:456–459. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matson BC, Corty RW, Karpinich NO, Murtha AP, Valdar W, Grotegut CA, Caron KM. Midregional pro-adrenomedullin plasma concentrations are blunted in severe preeclampsia. Placenta. 2014;35:780–783. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohno M, Hanehira T, Kano H, Horio T, Yokokawa K, Ikeda M, Minami M, Yasunari K, Yoshikawa J. Plasma adrenomedullin concentrations in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1996;27:102–107. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pang L, Qi J, Gao Y, Jin H, Du J. Adrenomedullin alleviates pulmonary artery collagen accumulation in rats with pulmonary hypertension induced by high blood flow. Peptides. 2014;54:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi K, Kitamura K, Hirayama N, Date H, Kashiwagi T, Ikushima I, Hanada Y, Nagatomo Y, Takenaga M, Ishikawa T, Imamura T, Koiwaya Y, Eto T. Increased plasma adrenomedullin in acute myocardial infarction. American heart journal. 1996;131:676–680. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larrayoz IM, Martinez-Herrero S, Garcia-Sanmartin J, Ochoa-Callejero L, Martinez A. Adrenomedullin and tumour microenvironment. Journal of translational medicine. 2014;12:339. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0339-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein KR, Caron KM. Adrenomedullin in lymphangiogenesis: from development to disease. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2015;72:3115–3126. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1921-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arulmani U, Maassenvandenbrink A, Villalon CM, Saxena PR. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and its role in migraine pathophysiology. European journal of pharmacology. 2004;500:315–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishimitsu T, Ono H, Minami J, Matsuoka H. Pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications of adrenomedullin in cardiovascular disorders. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2006;111:909–927. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Julian M, Cacho M, Garcia MA, Martin-Santamaria S, de Pascual-Teresa B, Ramos A, Martinez A, Cuttitta F. Adrenomedullin: a new target for the design of small molecule modulators with promising pharmacological activities. European journal of medicinal chemistry. 2005;40:737–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos CG, Sun X, Johnson EB, Nelson HE, Gonzalez Bosc LV. Adrenomedullin expression in the developing human fetal lung. Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research. 2014;62:49–55. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marinoni E, Di Iorio R, Alo P, Villaccio B, Alberini A, Cosmi EV. Immunohistochemical localization of adrenomedullin in fetal and neonatal lung. Pediatric research. 1999;45:282–285. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199902000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez A, Miller MJ, Catt KJ, Cuttitta F. Adrenomedullin receptor expression in human lung and in pulmonary tumors. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 1997;45:159–164. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagner S, Stahl U, Knoblauch B, McGregor GP, Lang RE. Calcitonin receptor-like receptor: identification and distribution in human peripheral tissues. Cell and tissue research. 2002;310:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vadivel A, Abozaid S, van Haaften T, Sawicka M, Eaton F, Chen M, Thebaud B. Adrenomedullin promotes lung angiogenesis, alveolar development, and repair. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2010;43:152–160. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0004OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.English J, Pearson G, Wilsbacher J, Swantek J, Karandikar M, Xu S, Cobb MH. New insights into the control of MAP kinase pathways. Experimental cell research. 1999;253:255–270. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kling DE, Lorenzo HK, Trbovich AM, Kinane TB, Donahoe PK, Schnitzer JJ. MEK-1/2 inhibition reduces branching morphogenesis and causes mesenchymal cell apoptosis in fetal rat lungs. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2002;282:L370–378. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00200.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim W, Moon SO, Sung MJ, Kim SH, Lee S, So JN, Park SK. Angiogenic role of adrenomedullin through activation of Akt, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and focal adhesion kinase in endothelial cells. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2003;17:1937–1939. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1209fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyashita K, Itoh H, Sawada N, Fukunaga Y, Sone M, Yamahara K, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Park K, Nakao K. Adrenomedullin provokes endothelial Akt activation and promotes vascular regeneration both in vitro and in vivo. FEBS letters. 2003;544:86–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iimuro S, Shindo T, Moriyama N, Amaki T, Niu P, Takeda N, Iwata H, Zhang Y, Ebihara A, Nagai R. Angiogenic effects of adrenomedullin in ischemia and tumor growth. Circulation research. 2004;95:415–423. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138018.61065.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang S, Patel A, Moorthy B, Shivanna B. Adrenomedullin deficiency potentiates hyperoxic injury in fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2015;464:1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]