Abstract

Purpose

Malawi is a low-income country in sub-Saharan Africa with limited health care infrastructure and high prevalance of HIV and tuberculosis. This study aims to determine the characteristics of patients presenting to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital Oncology Unit, Blantyre, Malawi, who had been treated for tuberculosis before they were diagnosed with cancer.

Methods

Clinical data on all patients presenting to the oncology unit at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital from 2010 to 2014 after a prior diagnosis of tuberculosis were prospectively recorded, and a descriptive analysis was undertaken.

Results

Thirty-four patients who had been treated for tuberculosis before being diagnosed with cancer were identified between 2010 and 2014, which represents approximately 1% of new referrals to the oncology unit. Forty-one percent of patients were HIV positive. Mean duration of tuberculosis treatment before presentation to the oncology unit was 3.6 months. The most common clinical presentation was a neck mass or generalized lymphadenopathy. Lymphoma was the most common malignancy that was subsequently diagnosed in 23 patients.

Conclusion

Misdiagnosis of cancer as tuberculosis is a significant clinical problem in Malawi. This study underlines the importance of closely monitoring the response to tuberculosis treatment, being aware of the possibility of a cancer diagnosis, and seeking a biopsy early if cancer is suspected.

INTRODUCTION

Malawi is a low-income country within sub-Saharan Africa and thus has a low number of trained medical personnel.1 Outside the main government central hospitals, most health care is delivered by nursing and clinical officer staff. Resources are scarce, and there are high levels of HIV, with a national seroprevalence rate of 10.0% in adults age 15 to 49 years (2014 data).2 Although the country has mounted an effective scale-up program of antiretroviral therapy, the rates of tuberculosis (156 per 100,000)3 and AIDS-related cancers, particularly lymphomas, are high. Cancer incidence in Malawi is estimated at 55.5 per 100,000 in males and 68.8 per 100,000 in females (age-standardized rates), and the most common cancer sites are Kaposi’s sarcoma, esophageal cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, cervical cancer, and breast cancer.4 Age-standardized incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is reported at 2.3 per 100,000 in males and 1.9 per 100,000 in females, considerably lower than the incidence of tuberculosis. Since the oncology unit at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) opened in 2010, it has registered more than 4,000 new patients with cancer, with diagnoses reflecting the distribution of cancer in Malawi.4 Several of the cancers are AIDS defining, the proportion of patients with cancer who are HIV positive is high (44% of new patients at the oncology unit were recorded as HIV positive in 2013 and 2014 combined), and some are co-infected with tuberculosis. Although tuberculosis rates in Malawi are reported by WHO to be lower than in some surrounding countries and are definitely dropping, they remain high, with tuberculosis treatment often based on clinical diagnosis alone.

The oncology team has been aware of some patients presenting with malignancy who have been erroneously diagnosed and treated for tuberculosis, thus delaying cancer care. The unit has been prospectively recording information about such instances, and we report on this.

METHODS

All patients presenting to the oncology unit at QECH from 2010 to 2014 were assessed by either a clinical officer (Y.J.), a consultant oncologist (L.P.L.M.), or both. Patients who had an erroneous tuberculosis diagnosis that delayed their cancer diagnosis were identified, and clinical data that included age, HIV status, clinical presentation, and type of malignancy were prospectively recorded and entered onto an Excel spreadsheet. A descriptive analysis of the data was undertaken. Ethics approval was gained through the Malawi Health Sciences Research Board.

RESULTS

Thirty-four patients who had been treated for tuberculosis before being diagnosed with cancer were identified between 2010 and 2014 (seven in 2010, nine in 2011, 11 in 2012, five in 2013, two from January through March 2014; Table 1). Forty-one percent of patients were HIV positive.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and HIV Status of Patients

Mean duration of tuberculosis treatment before oncology presentation was 3.6 months. The mean resultant delay in cancer diagnosis was 5.4 months. This was slightly longer for men (5.9 months) than for women (4.5 months).

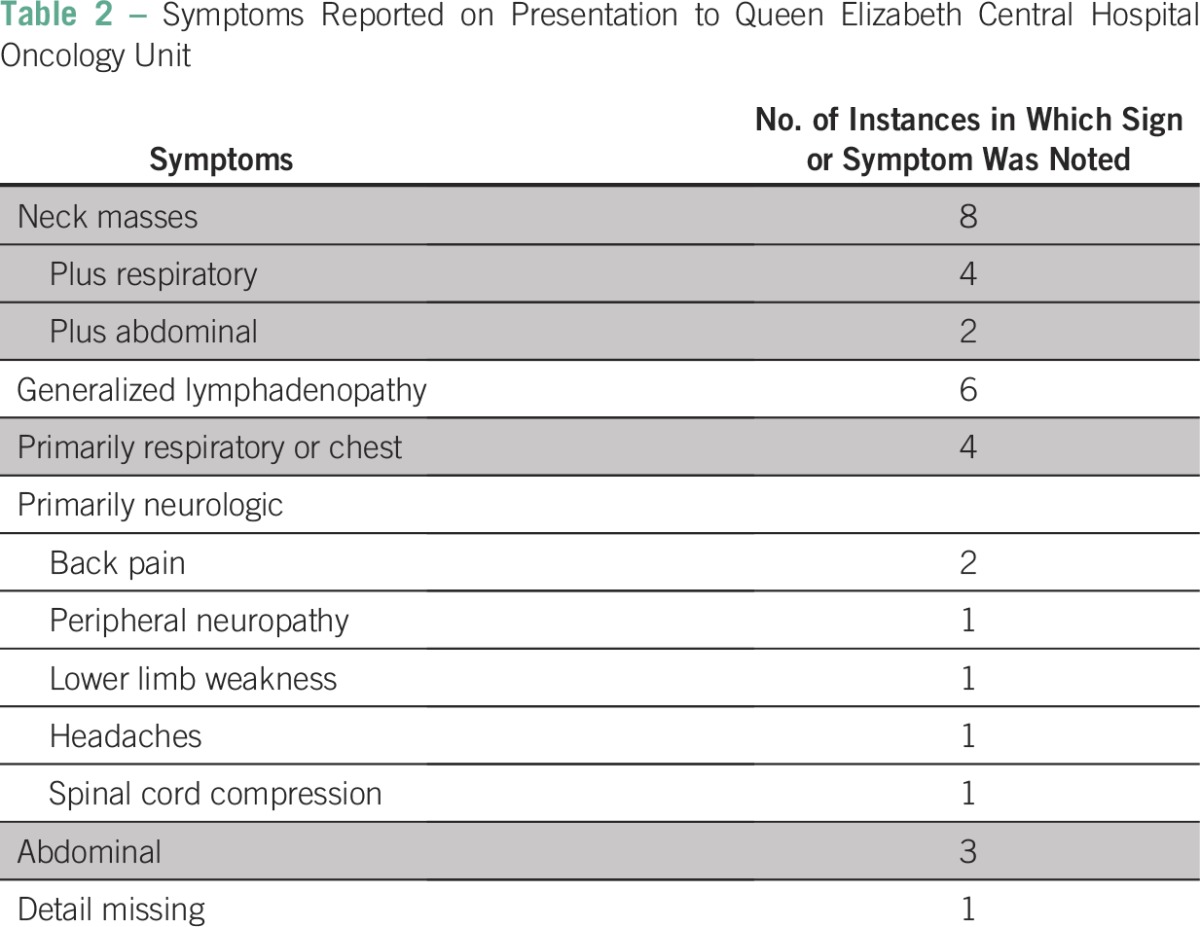

Many patients had a constellation of signs and symptoms on presentation, including prominent neck masses, fever, malaise, weight loss, cough, and abdominal pain (Table 2). Mean hemoglobin was 9.2 g/dl.

Table 2.

Symptoms Reported on Presentation to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital Oncology Unit

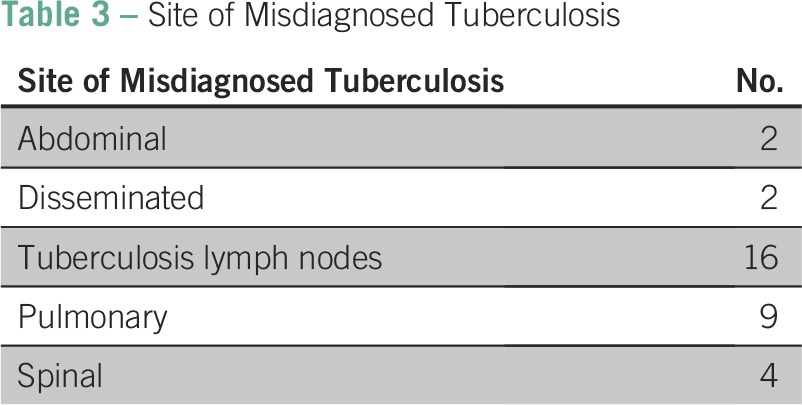

Misdiagnoses of tuberculosis were predominantly clinical (17 instances) but were often supported by chest x-ray (seven), other x-ray (two), ultrasound scan (one), fine-needle aspirate (one), magnetic resonance imaging (one), and cerebrospinal fluid analysis (one). The most common site for misdiagnosis of tuberculosis was lymph nodes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Site of Misdiagnosed Tuberculosis

The eventual cancer diagnosis was confirmed by histology or cytology in 33 of the 34 patients. The single patient with Kaposi’s sarcoma had a clinical diagnosis. The most common diagnosis was non-Hodgkin lymphoma followed by Hodgkin lymphoma (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cancer Diagnoses in Patients Treated as Having Tuberculosis (No. HIV positive)

Treatment was possible for many patients, and a chemotherapy regimen was offered to 26 patients. Four patients were not eligible for chemotherapy, two were given steroids, one patient had surgery combined with chemotherapy, and treatment was not recorded for one patient. The regimen used for the majority of patients was cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms that delay in diagnosing cancer caused by previous incorrect diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis is an important clinical problem in Malawi. Our figure of 34 misdiagnosed patients since 2010 represents approximately 1% of the oncology patients that presented to the QECH Oncology Unit. This misdiagnosis is well understood in the literature, notably in lymphomas5 and the lungs.6 In our series, the most common malignancies that were misdiagnosed were lymphoma followed by lung cancer. The delay in treatment in this series was 5.4 months, and this study reinforces the concerns raised about inappropriate tuberculosis care leading to delayed cancer diagnosis in a second Malawian central hospital.7 Therefore, cancer treatment for our patients often started at a later clinical stage in which outcomes may have been compromised.

Malawi has a large number of patients and few staff, particularly in rural areas with limited investigative capacity; as a consequence, the diagnosis of tuberculosis is sometimes made on clinical grounds alone. This contributed to misdiagnosis in 17 of 35 patients and is a common challenge for health care services in low-income countries, particularly for cancers that share features of presentation with tuberculosis.5

The majority of symptoms and signs described are common between tuberculosis and malignancy, especially the lymphomas. Given the limited investigative capacity and the common presentation of tuberculosis, the misdiagnoses are not unexpected, and similar findings have been found and similar explanations for the problem have been given in South Africa and elsewhere in Malawi.5,7

The empirical treatment of tuberculosis is common in Malawi, but when this is undertaken for extrapulmonary or smear-negative tuberculosis, close monitoring for response is important. Patients presenting with lymphadenopathy should be considered for biopsy referral because there is a high likelihood of cancer diagnosis: 53% and 35% in two Malawian series.7,8 Where biopsy and histopathologic facilities are available, a clinical diagnosis of tuberculosis for lymphadenopathy should be discouraged.

Follow-up of patients with tuberculosis in a resource-poor setting is notoriously difficult. Here, although the treatment was incorrect, this sample of patients often had complete or almost complete courses of tuberculosis treatment over several months under some form of clinical supervision, mostly by nursing and clinical officer staff. This creates an opportunity to intervene and offer training to health care staff and also provides an opportunity for health care institutions to improve their monitoring of response to tuberculosis treatment. Our findings raise the concern that patients with potentially treatable cancers may miss the opportunity to have access to cancer treatment because of misdiagnosis and emphasize the importance of more cancer awareness training for all health care staff.

Ensuring the microbiologic diagnosis of tuberculosis, promoting biopsies of patients with lymphadenopathy, and being more alert to the possibility of a cancer diagnosis in people who were originally diagnosed as having tuberculosis but who do not improve with treatment are all key to improving care for this group of patients. When the diagnosis is reviewed and cancer is correctly diagnosed and then treated promptly, a successful outcome for the patient is more likely. We recommend that health care workers have a low threshold for referring patients for investigation for malignancy if empirical tuberculosis treatment does not lead to a clinical response within 4 weeks. The Malawian Ministry of Health National Action Plan for Prevention and Management of Non-Communicable Disease in Malawi 2012-20169 plans initiatives to improve cancer knowledge in the general population and improve cancer education for health care providers. We hope that these and other initiatives will help improve outcomes for patients with cancer in Malawi.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Leo Peter Lockie Masamba, Yankho Jere, Dermot Robert Gorman

Collection and assembly of data: Leo Peter Lockie Masamba, Yankho Jere, Ewan Russell Stewart Brown

Data analysis and interpretation: Leo Peter Lockie Masamba, Ewan Russell Stewart Brown, Dermot Robert Gorman

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Tuberculosis Diagnosis Delaying Treatment of Cancer: Experience From a New Oncology Unit in Blantyre, Malawi

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Leo Peter Lockie Masamba

No relationship to disclose

Yankho Jere

No relationship to disclose

Ewan Russell Stewart Brown

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Dermot Robert Gorman

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO Statistical Information System . World Health Statistics 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Countries: Malawi—HIV and AIDS estimates (2014) http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/malawi.

- 3.World Health Organization Tuberculosis (TB): Tuberculosis country profiles—Malawi 2013. http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/

- 4.Msyamboza KP, Dzamalala C, Mdokwe C, et al. Burden of cancer in Malawi; common types, incidence and trends: National population-based cancer registry. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:149. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puvaneswaran B, Shoba B. Misdiagnosis of tuberculosis in patients with lymphoma. S Afr Med J. 2013;103:32–33. doi: 10.7196/samj.6093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatt M, Kant S, Bhaskar R. Pulmonary tuberculosis as differential diagnosis of lung cancer. South Asian J Cancer. 2012;1:36–42. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.96507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mabedi C, Kendig C, Liomba G, et al. Causes of cervical lymphadenopathy at Kamuzu Central Hospital. Malawi Med J. 2014;26:16–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mtonga P, Masamba L, Milner D, et al. Biopsy case mix and diagnostic yield at a Malawian central hospital. Malawi Med J. 2013;25:62–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Action Plan for Prevention and Management of Non-Communicable Disease in Malawi 2012-2016. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]