Abstract

Importance

Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR) is an under-recognized cause of heart failure (HF) in the elderly, owing in part to difficulty in diagnosis. ATTR can result from mutant TTR protein with one of the most common mutations in the United States, V122I, present in 3.43% of African Americans.

Objective

To determine whether serum retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), an endogenous TTR ligand, could be used as a diagnostic test for ATTR V122I amyloidosis.

Design

Combined prospective and retrospective cohort study

Setting

Tertiary care referral center

Participants

Fifty prospectively genotyped African American patients over age 60 years with non-amyloid HF and cardiac wall thickening, and a comparator cohort of biopsy proven ATTR V122I amyloidosis patients (n=25) comprised the development cohort. Twenty-seven prospectively genotyped African American patients and 9 ATTR V122I amyloidosis patients comprised the validation cohort.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Circulating RBP4, TTR, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and troponin I (TnI) concentrations, electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography, and clinical characteristics were assessed in all patients. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to identify optimal thresholds for ATTR V122I amyloidosis identification. A clinical prediction rule was developed using penalized logistic regression, evaluated using ROC analysis and validated in an independent cohort of cases and controls.

Results

Age, gender, BNP and TnI were similar between ATTR V122I amyloidosis patients and controls. Serum RBP4 concentration was lower in patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis compared to non-amyloid controls (31.5 vs. 49.4 ug/ml, p < 0.001) and the difference persisted after controlling for potential confounding parameters. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was lower in ATTR V122I amyloidosis (40% vs. 57%, p<0.001), while interventricular septal diameter (IVSd) was higher (16 vs. 14 mm, p<0.001). ROC analysis identified RBP4 as a sensitive identifier of ATTR V122I amyloidosis (AUC 0.78). A clinical prediction algorithm comprised of RBP4, TTR, LVEF, IVSd, mean limb lead ECG voltage and grade 3 diastolic dysfunction yielded excellent discriminatory capacity for ATTR V122I amyloidosis (AUC 0.97), while a 4 parameter model including RBP4 concentration retained excellent discrimination (AUC 0.92). The models maintained excellent discrimination in the validation cohort.

Conclusions and Relevance

A prediction model employing circulating RBP4 concentration and readily available clinical parameters accurately discriminated ATTR V122I amyloid cardiomyopathy from non-amyloid HF in a case matched cohort. We propose that this clinical algorithm may be useful for identification of ATTR V122I amyloidosis in elderly, African American patients with heart failure.

Introduction

Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR) results from misaggregation and myocardial deposition of wild-type (ATTRwt) or mutated (ATTRm) TTR protein, increasing ventricular wall thickness, inducing heart failure, and ultimately death (1,2). Several single amino acid substitutions have been associated with ATTRm cardiac amyloidosis. Most notably, substitution of valine for isoleucine at codon 122 of the TTR gene (V122I) constitutes one of the most prevalent familial TTR amyloidoses in the United States. The V122I mutation is present in 3.43% African Americans(3) while generally absent in Caucasians(4). ATTRm V122I amyloidosis carries significant morbidity and mortality(1, 5). Unfortunately, identification generally occurs after the development of symptoms and a large number of patients with the disease are misdiagnosed or undiagnosed(6, 7). Recent advances in pharmacologic therapy for ATTR have led to the development of targeted treatments with promising results in clinical trials(8–10). Therefore, there is a pressing need for better testing to permit recognition of disease, and to differentiate ATTR V122I amyloidosis from other causes of heart failure in at risk patients.

At present, definitive diagnosis of ATTR cardiomyopathy requires Congo red staining of a cardiac biopsy, biochemical or immunochemical demonstration of TTR as the pathologic protein, and TTR genotyping. Although cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging can identify cardiac amyloidosis(11), it does not provide conclusive information regarding amyloid disease type. Bone-avid technetium pyrophosphate (Tc99m-PYP) or DPD nuclear scanning is rapidly emerging as a tool for cardiac ATTR identification(12), however, these tests require experience to perform and interpret, and while increasing in utilization, have not yet achieved widespread adaptation.

Normally, TTR circulates as a homotetramer complexed to retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), a 21 kDa protein integral to the transport of all-trans retinol (vitamin A). When bound to TTR, the RBP4-retinol complex stabilizes the TTR tetramer inhibiting monomer dissociation and amyloid fibril formation(13). Additionally, RBP4 binding to the TTR tetramer prevents glomerular filtration of low molecular weight RBP4, effectively increasing its circulating levels(14). It is widely held that mutations encode destabilizing amino-acid replacements that induce TTR tetramer disassociation resulting in fewer circulating RBP4-TTR complexes and increased urinary excretion of RBP4(15). Alternatively, it is conceivable that decreased plasma concentration of RBP4 could result in lower TTR binding, thereby promoting tetramer destabilization. These observations suggest that RBP4 concentration may indicate the degree of TTR misfolding, and therefore amyloid fibril formation. We sought to determine the utility of circulating RBP4 as a tool to identify ATTR V122I amyloidosis in a cohort of elderly African American patients with heart failure. We further aimed to develop a clinical prediction model for ATTR V122I amyloidosis based on clinical, echocardiographic and electrocardiographic parameters, along with RBP4 and other cardiac biomarkers.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a case control study involving self-reported African Americans with cardiomyopathy either due to biopsy proven ATTR V122I amyloidosis or non-amyloid causes. The study was divided in two parts - the development and validation cohorts. For the development cohort, we prospectively recruited and genotyped a population of elderly African American patients with cardiomyopathy (n=52) from September 2014 to December 2015. Inclusion criteria for the prospective cohort were age ≥60 years, African American race, an ICD-9/10 diagnosis of heart failure, and interventricular septal diameter ≥12mm as determined by echocardiography. Those who proved to have normal TTR genotype (n=50) comprised the non-amyloid control cohort. Those who proved to have ATTR V122I amyloidosis (n=2, demonstrated to be phenotype positive) were ultimately included in the validation cohort (see below). For the cases of the development cohort, patient sera and clinical data from n=25 patients with biopsy proven ATTR V122I amyloidosis collected between September 2009 and November 2014 were obtained retrospectively from the Boston University Amyloidosis Center archive and repository. Light chain amyloidosis was excluded by plasma cell dyscrasia marker analysis (serum free light chain assays, serum and urine immunofixation electrophoreses) or amyloid typing of a cardiac biopsy (36% of total ATTR cohort). Sera from both cohorts were tested for TTR and RBP4 concentration; prospectively collected samples were analyzed for TTR genotype. Height, weight and blood pressure, medical history including hypertension and diabetes, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic parameters, hematocrit, creatinine, lipid levels, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and troponin I (TnI) levels were obtained from the clinical medical record.

For the validation cohort, we prospectively recruited an additional n=27 patients elderly African Americans with non-amyloid cardiomyopathy between December 2015 and July 2016 (using the same enrollment criteria as the initial part of the study) and identified an additional patient with ATTR V122I amyloidosis (total n=3 prospectively identified patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis, 2 from the initial study period and one during the validation study recruitment). To enrich the validation cohort with additional ATTR V122I amyloidosis cases, we included 6 additional biopsy-proven ATTR V122I amyloidosis individuals seen at the Boston University Amyloidosis Center between July 2014 and July 2016. The total validation group was comprised of 9 ATTR V122I amyloidosis cases and 27 controls (see also Supplemental Methods and Supplemental Figure 1).

Serum protein quantification and identification of TTR V122I

Blood samples were obtained at initial visit to our clinic and stored at −80 °C until required for analyses. RBP4 concentrations were determined from each sample via commercially available ELISA assays (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Testing was performed in triplicate and average values reported. Precision of RBP4 concentration measurements was reflected in the intra- and inter-assay precision coefficients of variation which were 5.7–8.1 % and 5.8–8.6 % respectively. TTR concentrations were determined in the clinical laboratory of the Pathology Department of Boston Medical Center by immunoturbidity assay (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Determination of TTR genotype was performed at the Boston University Amyloidosis Laboratory via a two-step process involving serum screening for a TTR mutant protein by isoelectric focusing (IEF) as previously described (5), and identification of the TTR mutation by direct nucleotide sequencing of amplified genomic DNA on samples where a mutant was detected. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sequencing of all 4 exons was performed for completeness to identify multiple mutations, as opposed to targeted PCR for exon 4 containing the V122I polymorphism. The patients identified as V122I carriers from the prospective analysis were subsequently referred to the Boston University Amyloidosis Center for confirmation of cardiac amyloid phenotype by advanced imaging (cardiac magnetic resonance or technetium pyrophosphate test) and/or by endomyocardial biopsy. In the prospective arm, technicians and investigators analyzing the samples for biomarkers and performing chart review of clinical, echocardiographic and electrocardiographic parameters were blinded to the results of genotyping for V122I during data collection.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test or t-test for continuous variables (depending on the distribution of data) and Chi-square tests for categorical variables were used in pairwise comparisons between participants with ATTR V122I amyloidosis and non-amyloid heart failure controls. Associations between continuous variables were assessed using the Spearman correlations. To assess whether RBP4 was independently associated with ATTR V122I amyloidosis, logistic regression was performed while controlling for potential confounders including age, gender, BMI, history of diabetes, cardiac biomarkers, and echocardiographic parameters. The ability of RBP4 to discriminate between ATTR V122I amyloidosis and non-amyloid cardiomyopathy was assessed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and calculation of the sensitivity and specificity of different RBP4 thresholds for the diagnosis of ATTR V122I amyloidosis by the ROC thresholds(16).

For the development of an assessment tool that maximized the diagnostic potential of non-invasive parameters, multivariable logistic regression models were created using independent variables pre-selected as having a potentially useful diagnostic role based in prior studies on ATTR V122I amyloidosis and on biological data. For patients that had missing values in at least one of the predictor variables (n=37), multiple imputation was performed using predictive mean matching to fill-in the missing values(17). Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was used to select the predictors of ATTR V122I amyloidosis that provided optimal diagnostic value while minimizing over-fitting(18). The LASSO regression shrinkage parameter was determined using 10-fold cross-validation within each imputed dataset. Details regarding the logistic regression analysis for the prediction rule for ATTR V122I amyloidosis can be found in the Supplemental Material. The goodness of fit of the LASSO regression prediction rule to the patient data was estimated by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test(19) and by drawing calibration plots. To visualize the results of the model and its diagnostic potential, we plotted the ROC curve from the predicted probabilities from the rule and the ATTR V122I amyloidosis diagnosis. ROC analysis allowed us to evaluate sensitivity and specificity values for different thresholds of the prediction rule. The prediction rule was subsequently tested on the validation cohort to assess its discrimination and goodness-of-fit. R statistical software version 2.3.2(20) was used in all statistical analyses. Multiple imputation with predictive mean matching was performed using the mice R package(17), while LASSO regression was performed with the glmnet package(18), and the ROC analysis used the pROC package(16). Statistical significance was set at a significance level of 0.05 for all comparisons.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board and all patients provided written consent before inclusion in the study.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

Of the 52 patients enrolled in the prospective portion of the development dataset, two were found to have ATTR V122I amyloidosis, amounting to a 3.8% calculated prevalence of the disease, as previously reported(3). Mean values of different clinical, biomarker, and echocardiographic parameters at study entry for patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis and non-amyloid heart failure are listed in Table 1. Age and gender did not differ significantly between the groups. Patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis had significantly lower BMI (p=0.006) and lower systolic blood pressure (p<0.001) at the time of enrollment, while diastolic blood pressure did not differ significantly. These differences persisted in models adjusting for age and gender.

Table 1.

Baseline differences between V122I ATTR and non-amyloid heart failure patients

| Variable | Patients with V122I ATTR* (N=25) | Patients with non-amyloid heart failure* (N=50) | Unadjusted p-value | Adjusted p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 72.2 ± 7.4 | 69.2 ± 5.7 | 0.1 | NA |

| Male gender | 18 (72) | 31(62) | 0.5 | NA |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 29.2 ± 6.1 | 34.4 ± 8.98 | 0.006 | 0.04 |

| History of diabetes | 8 (32) | 29 (58) | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 117 ± 18 | 138 ± 20 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 76 ± 9 | 77 ± 11 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| RBP4 (ug/ml) | 31.47 ± 9.09 | 49.36 ± 20.59 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| TTR (mg/dl) | 16.47 ± 5.51 | 23.98 ± 6.85 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| RBP4/TTR | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 7.2 ± 2.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 83 ± 27 | 120 ± 98 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 160 ± 34 | 152 ± 40 | 0.2 | 0.08 |

| BNP (ng/L) | 897 ± 657 | 1028 ± 2706 | 0.004 | 0.7 |

| Troponin (ng/ml) | 0.274 ± 0.251 | 0.133 ± 0.373 | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.47 ± 0.43 | 1.80 ± 1.12 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 40.5 ± 6.6 | 37.1 ± 6.0 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

BMI: body mass index, BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide, BP: blood pressure, HbA1C: Hemoglobin A1C, RBP4: retinol binding protein 4, TTR: transthyretin.

All continuous values are in the form mean (±sd), while all categorical values are in the form n (%)

P-value is adjusted for age and gender based on logistic regression models

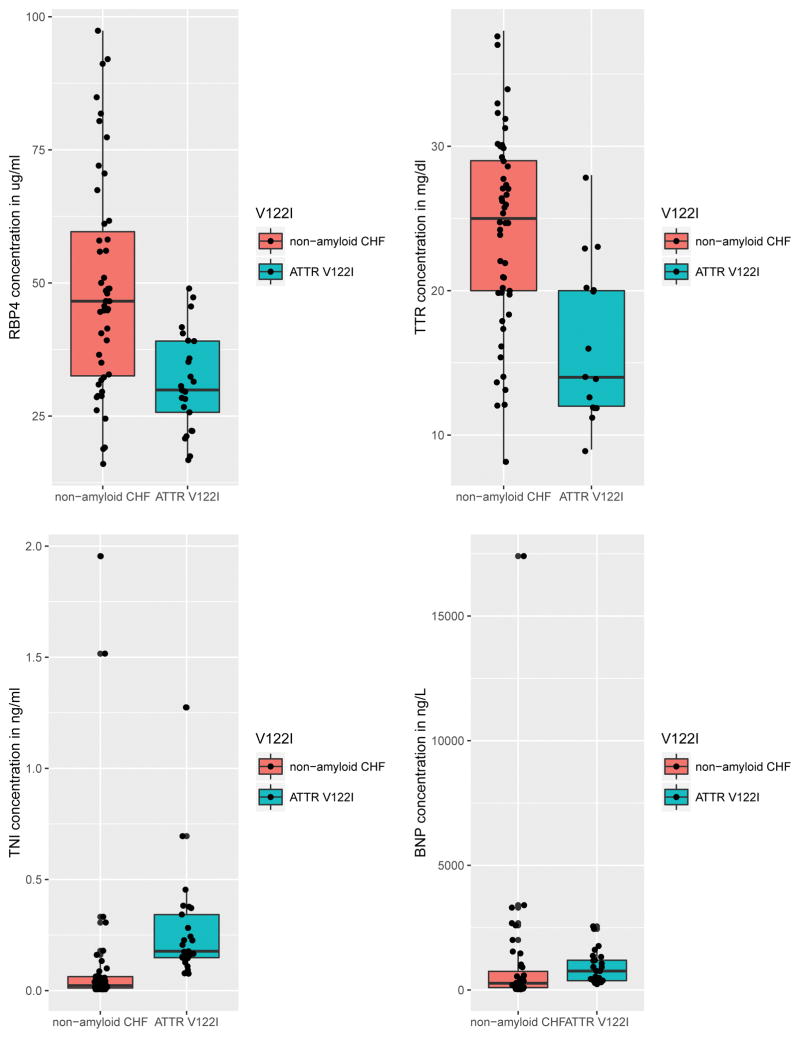

Patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis had significantly lower levels of RBP4 (p<0.001), TTR (p<0.001) and BNP (p=0.004), and higher levels of troponin I (p<0.001) and hematocrit (p=0.02) compared to non-amyloid controls (Figure 1). The two groups did not differ in the levels of hemoglobin A1C, triglycerides, total cholesterol or serum creatinine. Moreover, the ratio of RBP4 to TTR was not different between the two groups (p=0.3). In models adjusting for age and gender, the differences in RBP4 and TTR remained significant, while BNP and troponin I were not found to be significantly different.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of serum biomarkers including BNP, TnI, RBP4, and TTR. Note that BNP and TnI are both well above normal limits and inconsistently increased in V122I ATTR, whereas RBP4 and TTR are both lower. Solid bars reflect median values and interquartile range.

Patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis had higher myocardial wall thickness as measured by interventricular septal diameter (p<0.001) and lower left ventricular ejection fraction (p<0.001) compared to controls. While present, these differences are well within the expected spectrum of wall thickness and systolic function, and clinically insufficient to differentiate the two populations. The two populations did not differ in LV mass index (p=0.2). Notably, the myocardial contraction fraction(21) was significantly lower in ATTR V122I amyloidosis compared to controls (p<0.001). Electrocardiographically, heart rate was higher in patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis (p=0.003) while mean limb lead QRS voltage (p<0.001) and QRS voltage to LV mass ratio (p<0.001) were lower. All of these findings persisted in age and gender adjusted models (Table 2).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic and ECG differences between V122I ATTR and non-amyloid heart failure patients

| Variable | Patients with V122I ATTR* (N=25) | Patients with non-amyloid heart failure* (N=50) | Unadjusted p-value | Adjusted p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 40 ± 14 | 57 ± 14 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IVSd (mm) | 16 ± 3 | 14 ± 2 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| PWd (mm) | 16 ± 3 | 14 ± 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| RWT (mm) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.002 | 0.05 |

| LV mass index (g/m) | 167.7 ± 42.7 | 158.0 ± 52.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| MCF (%) | 23 ± 13 | 49 ± 13 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Grade 3 diastolic dysfunction | 14 (56) | 4 (8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Electrocardiographic parameters | ||||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 78 ± 11 | 70 ± 15 | 0.003 | 0.03 |

| PR interval (msec) | 192 ± 45 | 178 ± 46 | 0.05 | 0.4 |

| QRS interval (msec) | 110 ± 27 | 109 ± 33 | 0.5 | 1 |

| QTc interval (msec) | 479 ± 42 | 461 ± 43 | 0.05 | 0.1 |

| Mean limb lead QRS voltage (mm) | 5 ± 2 | 8 ± 3 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Voltage/LV mass (mm/g) | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Presence of AF | 5 (20) | 8 (16) | 0.9 | 0.9 |

AF: atrial fibrillation, ECG: electrocardiogram, IVSd: Interventricular septum diameter, LV: left ventricle, LVEF: left ventricle ejection fraction, MCF: myocardial contraction fraction, PWd: posterior wall diameter, RWT: relative wall thickness, TTR: transthyretin.

All continuous values are in the form mean ±sd, while all categorical values are in the form n (%)

P-value is adjusted for age and gender based on logistic regression models

RBP4 concentration and ATTR V122I cardiac amyloidosis identification

As RBP4 concentration was significantly lower in patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis, we performed multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess whether this association was affected by confounding variables. RBP4 concentration remained significantly different when controlling for age, sex, BMI, history of diabetes, creatinine, nutritional status (albumin, modified body mass index (BMI)), hematocrit, cardiac biomarkers and echocardiographic parameters. Not surprisingly, RBP4 and TTR levels were highly correlated (Spearman rho=0.75, p<0.001) and consequently the association between RBP4 and ATTR V122I amyloidosis was not statistically significant when both RBP4 and TTR were included in the same logistic regression model.

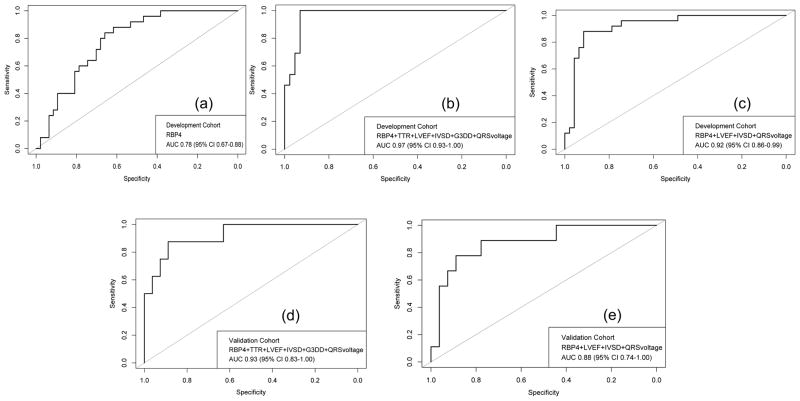

ROC analysis identified RBP4 as a potentially sensitive diagnostic test for ATTR V122I amyloidosis cardiomyopathy (AUC 0.78, 95% CI 0.67–0.88) (Figure 2a). A threshold of 43 ug/ml maximized the Youden index, providing a sensitivity of 62% (95% CI: 47%–77%) and a specificity of 88% (95% CI 76%–100%) for ATTR V122I amyloidosis. For the purposes of screening, a cut-off value of 50 ug/mL achieved perfect sensitivity (100% with 95% CI, 100–100%) but low specificity (38% with 95% CI, 23–51%) for ATTR V122I amyloidosis. This threshold also yielded a negative predictive value (NPV) of 100% in this total population with 33% prevalence of the disease. Importantly, 38% of the non-amyloid control cohort had RBP4 values above this threshold.

Figure 2.

a. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of RBP4 concentration in the diagnosis of V122I cardiac amyloidosis.

b. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the full clinical model in the diagnosis of V122I cardiac amyloidosis on the development cohort. Variables included RBP4 concentration, LV ejection fraction, interventricular septal thickness, TTR concentration, mean limb lead voltage, and the presence of grade 3 diastolic dysfunction.

c. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the parsimonious model calculated by our sensitivity analysis in the diagnosis of V122I cardiac amyloidosis on the development cohort. Variables included RBP4 concentration, LV ejection fraction, interventricular septal thickness, and mean limb lead voltage.

d. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the full clinical model in the diagnosis of V122I cardiac amyloidosis on the validation cohort. Variables included RBP4 concentration, LV ejection fraction, interventricular septal thickness, TTR concentration, mean limb lead voltage, and the presence of grade 3 diastolic dysfunction.

e. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the parsimonious model calculated by our sensitivity analysis in the diagnosis of V122I cardiac amyloidosis on the validation cohort. Variables included RBP4 concentration, LV ejection fraction, interventricular septal thickness, and mean limb lead voltage.

Diagnostic Model for V122I ATTR

To improve diagnostic performance, we developed a model for V122I ATTR identification using several pre-determined clinical factors, circulating biomarkers, and echocardiographic parameters. In addition to RBP4 and TTR concentrations, we selected six variables available to clinicians by standard of care testing including LVEF, IVSd, presence of grade 3 diastolic dysfunction, and mean limb lead QRS voltage, which significantly improved the final prediction rule. All other clinical parameters (age, gender), circulating biomarkers (hemoglobin A1C, triglycerides, total cholesterol, BNP, troponin I) and other electrocardiographic measures did not add significant diagnostic value and were excluded from the final model. Of note, our diagnostic model development is compliant with the TRIPOD statement for transparent reporting(22) (see also Supplemental Table 1).

The following prediction rule was developed as a result of this statistical modeling:

Figure 2b shows the ROC curve for the prediction model. ROC analysis identified the diagnostic model as an efficient discriminator of V122I ATTR with an AUC of 0.97 (95% CI 0.93–1.00). Notably, the AUC of the model did not vary significantly among the different imputation datasets (range 0.96–0.97). When applied to our original dataset, the prediction rule did not demonstrate any statistical evidence of poor fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow p-value>0.2, see also Supplemental Figure 2a). Of note, the median probability of control patients based on the prediction model was 11.2% (interquartile range (IQR) 7.9%–15.6%) whereas the median probability of the ATTR V122I amyloidosis individuals was 48.3% (IQR 38.4%–68.9%) suggesting that a probability threshold of >30% for any given patient could be employed to trigger further diagnostic testing for V122I cardiac amyloidosis.

Sensitivity analysis

Recognizing the structural association of TTR and RBP4, we performed a sensitivity analysis using the same statistical methodology excluding TTR from the model as well as the presence of grade 3 diastolic dysfunction due to its relative subjectivity (see Supplemental Methods). The resulting 4-variable model incorporating only RBP4, LVEF, IVSd, and mean limb lead QRS voltage was:

This final model maintained excellent discriminatory capacity for ATTR V122I amyloidosis with a ROC curve AUC of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.86–0.99) (Figure 2c) and no evidence of poor fit to our original dataset (Hosmer-Lemeshow p-value>0.4, see also Supplemental Figure 2b)

Validation

Both the six-parameter model and the parsimonious model were evaluated for their performance in the validation cohort. The discrimination of both models remained excellent in the validation set (ROC AUC 0.93 (95% CI: 0.83–1) for the full model and 0.88 (95% CI: 0.74–1) for the parsimonious model, see also Figures 2d and 2e), while none of the models showed any evidence of poor fit to the replication cohort (Hosmer-Lemeshow p-value>0.5 for both models, see also Supplemental Figures 3a and 3b). Importantly, one of the patients in the validation group was identified as being V122I TTR genotype positive but showed no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia nor amyloid on pyrophosphate scan, thus presumed to be genotype positive-amyloid phenotype negative. This individual’s probability of ATTR V122I amyloidosis by our predictive models was low (10.4% by the full model and 11.6% by the parsimonious model), providing further confidence in the validity of our predictive model..

Discussion

ATTR V122I amyloidosis is an under-recognized cause of heart failure in elderly African Americans owing to the complexities of diagnosis and the prevalence of hypertensive heart disease in the target cohort. To facilitate identification and testing of a population at-risk for ATTR V122I amyloidosis, we developed a novel mathematical prediction of disease based on LV ejection fraction, RBP4 concentration, interventricular septal wall thickness, and mean limb lead voltage, yielding a likelihood of ATTR V122I amyloidosis in African Americans older than 60 years with heart failure. We submitted this model to rigorous statistical testing to confirm its quality of fit, demonstrating excellent discriminative capacity for ATTR V122I amyloidosis identification (AUC > 0.9) which was subsequently confirmed in an independent validation cohort. The model may therefore be useful to guide clinicians as to whether a patient who fits the at risk population will require further diagnostic testing, such as Tc99m PYP/DPD testing(12), or heart biopsy. Importantly, when analyzed individually, the specific parameters employed in the model proved insufficient to identify ATTR V122I amyloidosis.

The demographics and cardiac measures exhibited by our study cohort were consistent with previous reports of V122I patients. Restrictive filling (grade 3 diastolic dysfunction) was higher and mean limb QRS voltage lower in patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis. Notably, in our study, patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis had higher troponin but lower BNP compared to non-amyloid heart failure patients but these results did not persist after controlling for age and gender. Previous studies have shown that BNP and troponin I tend to be higher in ATTR V122I amyloidosis patients (1) but differences in BNP were not found in other reports(5). While the vast majority of recruited control patients were identified during a clinically stable outpatient visit, we should note that it is possible that the cardiac biomarkers in our control population could have been skewed toward higher values as this information was collected from chart review and would thereby be biased by the clinical indication for collection of these biomarkers in this group. Interestingly, our results showed that individuals with V122I ATTR had lower LVEF and higher wall thickness but did not differ in LV mass index. This is in agreement with some prior reports of elderly patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis(1, 5) but contrary to the findings of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study(22). This could reflect the fact that the ARIC study included carriers of the V122I mutation without limiting the population to patients with confirmed disease, skewing the echocardiographic indicators toward the general control population. Indeed, the median age of patients from the ARIC study at inclusion was 52 years, with the echocardiographic measurements being obtained at visit 5 (approximately 8 years later). Previous reports indicate that before the age of 65 years, there is no discernible impact of the V122I mutation in cardiac function(23). Similarly, in another cohort of elderly patients, the LVEF decreased on average by 3.2% in every 6-month interval of follow up(1).

RBP4 was significantly associated with mutant TTR amyloid cardiomyopathy independent of potentially confounding variables. To our knowledge, this association has not been previously reported in the clinical setting but in-vitro disease models have shown a potential role of RBP4 in stabilizing TTR and preventing misfolding(24). We demonstrate that RBP4 concentration greater than or equal to 49.5 ug/ml had 100% sensitivity (but modest specificity) and provided 100% negative predictive value in excluding ATTR V122I amyloidosis without the need for further testing (similar in the way that D-dimer concentration is utilized to exclude venous thrombo-embolism), suggesting a potential utility of RBP4 concentration as an initial screening test.(25).

Limitations of our study include the relatively small number of patients, although the number of patients with ATTR V122I amyloidosis in the context of world-wide prevalence estimates is reasonably sized. Since the prediction rule was developed in elderly African American individuals, we cannot generalize our findings to the general population of patients with heart failure, to younger populations, nor to ATTRm from other amyloidogenic mutations. The results presented here should be seen as promising but preliminary. Although the prediction rule performance estimates remained excellent in a small replication cohort, external validation in a larger, independent patient population will be necessary before widespread clinical adaptation. Finally, while we definitively established ATTR V122I cardiac amyloidosis, a small possibility exists that our control group included a case of cardiac amyloidosis not attributable to ATTR V122I (i.e., AL amyloidosis or ATTRwt). The proportion of these individuals is expected to be small, if present at all, given that the known annual incidence of AL cardiac amyloidosis is extremely low (~ 1:100,000 US population)(25), and in a large recent cohort of ATTRwt, >90% of patients with ATTRwt were Caucasian males and not African American(26). Further, even if a small minority of our controls had some other form of cardiac amyloid, this would not be expected to lead to an overestimate of our predictive model performance but would rather decrease the specificity (and subsequently the AUC) of our model by increasing the number of false positives.

In summary, we demonstrate a clinical prediction model based upon RBP4 concentration and available standard of care clinical variables that has the potential to identify ATTR V122I amyloidosis and thereby trigger confirmatory testing. The test may have clinical utility as a first-line screening test for the disease in elderly African Americans with heart failure, guiding clinical decision making. Furthermore, RBP4 concentration alone or in the context of this model may be useful to follow disease progression. Prospective validation of our disease model in larger clinical cohorts is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH R21AG050206 (FLR), R01AG031804 (LHC), 1U54TR001012 (FLR), and the Young Family Amyloid Research Fund. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. MA and FLR had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Ruberg FL, Maurer MS, Judge DP, et al. Prospective evaluation of the morbidity and mortality of wild-type and V122I mutant transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Cardiac Study (TRACS) Am Heart J. 2012;164(2):222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson DR, Pastore RD, Yaghoubian R, et al. Variant-sequence transthyretin (isoleucine 122) in late-onset cardiac amyloidosis in black Americans. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(7):466–473. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobson DR, Alexander AA, Tagoe C, Buxbaum JN. Prevalence of the amyloidogenic transthyretin (TTR) V122I allele in 14 333 African-Americans. Amyloid. 2015;22(3):171–174. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2015.1051219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamashita T, Hamidi Asl K, Yazaki M, Benson MD. A prospective evaluation of the transthyretin Ile122 allele frequency in an African-American population. Amyloid. 2005;12(2):127–130. doi: 10.1080/13506120500107162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connors LH, Prokaeva T, Lim A, et al. Cardiac amyloidosis in African Americans: comparison of clinical and laboratory features of transthyretin V122I amyloidosis and immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis. Am Heart J. 2009;158(4):607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damy T, Costes B, Hagege AA, et al. Prevalence and clinical phenotype of hereditary transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in patients with increased left ventricular wall thickness. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(23):1826–1834. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruberg FL, Berk JL. Transthyretin (TTR) cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2012;126(10):1286–1300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, et al. Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(24):2658–2667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurer MS, Grogan DR, Judge DP, et al. Tafamidis in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: effects on transthyretin stabilization and clinical outcomes. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(3):519–526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coelho T, Adams D, Silva A, et al. Safety and efficacy of RNAi therapy for transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontana M, Pica S, Reant P, et al. Prognostic Value of Late Gadolinium Enhancement Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circulation. 2015;132(16):1570–1579. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, et al. Nonbiopsy Diagnosis of Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2404–2412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghu P, Sivakumar B. Interactions amongst plasma retinol-binding protein, transthyretin and their ligands: implications in vitamin A homeostasis and transthyretin amyloidosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1703(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei S, Episkopou V, Piantedosi R, et al. Studies on the metabolism of retinol and retinol-binding protein in transthyretin-deficient mice produced by homologous recombination. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(2):866–870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berni R, Malpeli G, Folli C, et al. The Ile-84-->Ser amino acid substitution in transthyretin interferes with the interaction with plasma retinol-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(38):23395–23398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z. Multiple imputation with multivariate imputation by chained equation (MICE) package. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(2):30. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.12.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33(1):1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, Lemeshow S. A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med. 1997;16(9):965–980. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970515)16:9<965::aid-sim509>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tendler A, Helmke S, Teruya S, Alvarez J, Maurer MS. The myocardial contraction fraction is superior to ejection fraction in predicting survival in patients with AL cardiac amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2015;22(1):61–66. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2014.994202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quarta CC, Buxbaum JN, Shah AM, et al. The amyloidogenic V122I transthyretin variant in elderly black Americans. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):21–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buxbaum J, Alexander A, Koziol J, et al. Significance of the amyloidogenic transthyretin Val 122 Ile allele in African Americans in the Arteriosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) and Cardiovascular Health (CHS) Studies. Am Heart J. 2010;159(5):864–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyung SJ, Deroo S, Robinson CV. Retinol and retinol-binding protein stabilize transthyretin via formation of retinol transport complex. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5(12):1137–1146. doi: 10.1021/cb100144v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyle RA, Linos A, Beard CM, et al. Incidence and natural history of primary systemic amyloidosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950 through 1989. Blood. 1992;79(7):1817–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connors LH, Sam F, Skinner M, et al. Heart Failure Resulting From Age-Related Cardiac Amyloid Disease Associated With Wild-Type Transthyretin: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. Circulation. 2016;133(3):282–290. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.