Abstract

RNA-based diagnosis and prognosis of squamous cell carcinoma has been slow to come to the clinic. Improvements in RNA measurement, statistical evaluation, and sample preservation, along with increased sample numbers, have not made these methods reproducible enough to be used clinically. We propose that, in the case of squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, a chief source of variability is sample dissection, which leads to variable amounts of stroma mixed in with tumor epithelium. This heterogeneity of the samples, which requires great care to avoid, makes it difficult to see changes in RNA levels specific to tumor cells. An evaluation of the data suggests that, paradoxically, brush biopsy samples of oral lesions may provide a more reproducible method than surgical acquisition of samples for miRNA measurement. The evidence also indicates that body fluid samples can show similar changes in miRNAs with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) as those seen in tumor brush biopsy samples–suggesting much of the miRNA in these samples is coming from the same source: tumor epithelium. We conclude that brush biopsy or body fluid samples may be superior to surgical samples in allowing miRNA-based diagnosis and prognosis of OSCC in that they feature a rapid method to obtain homogeneous tumor cells and/or RNA.

Few Successes for RNA-Based Diagnosis or Prognosis of Cancer

Well over a decade ago the first studies were published that attempted to allow the identification of head and neck and, more narrowly, oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) based on gene expression [1–3]. These studies relied on surgical biopsy to obtain tissue from which RNA was purified then analyzed. Unfortunately, for a number of reasons, this work did not lead to a method of tumor detection superior to that of histopathology of surgically obtained tissue by single biopsy, which is accurate 90% of the time [4]. While it has long been known that normal tissue expresses different RNAs than OSCC tissue [5], production of an RNA-based classifier to accurately differentiate tumor from normal has seen slow progress despite early advances [6, 7]. Distinction between benign and malignant disease is even more difficult to achieve [8]. Work with miRNAs found the same: Classifiers designed to diagnose or provide a prognosis for oral lesions worked well when first developed, but less well when applied to external datasets [8–11]. RNA-based classifiers for other cancers have been approved for usage in the clinic [12, 13]. Only one group of tests, which measure breast tumor RNA to predict treatment outcomes, represented by Oncotype DX and Mammaprint have met with wide, well-deserved acceptance as they clearly improve on the standard of care [14–16].

Possible Explanation for Poor Results in Diagnosis Using OSCC Tumor RNA

Over the years there have been many explanations for the poor function of RNA-based classifiers for OSCC detection when tested on external datasets (Table 1). Initially flawed statistical analysis was a major problem [17, 18]. When this was largely eliminated as a source of error other causes were suggested to explain the persistent problem. This included usage of different platforms to measure RNA, inter-tumor heterogeneity in RNA expression, variability in sample dissection, the limited size of most sample datasets, and cohort differences in head and neck cancer etiology etc. [1, 10, 19]. With time, platform-dependent differences in RNA measurement results have been greatly reduced, though those for miRNA still can occur [20–22]. Recent works suggest that inter-tumor heterogeneity and varied tumor etiology seem to contribute little to problems in RNA-based OSCC detection. Inter-tumor heterogeneity in RNA expression was originally reported for head and neck tumors in 2004 but was not corroborated till 2014 [23, 24]. Four to six different classes of HNSCC tumors have been proposed based on mRNA and to some degree miRNA expression [23–26]. Most if not all of these subclasses are also found among oral tumors. The question arose that if these subclasses show substantially different RNA expression, then RNA-based detection of OSCC may be made difficult. Large studies like that of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), where hundreds of OSCC samples were measured, allowed construction of classifiers with a subset of samples for training the classifier, then usage of a second subset of samples from the same dataset for external validation. These, of course, would be obtained, dissected and prepared by the same group [25]. When this was done using RNA profiles from a subgroup of TCGA database, external validation with a miRNA-based classifier revealed near 100% accuracy in differentiating normal tissue from tumor tissue [27]. The accuracy of class prediction in two somewhat smaller studies was almost as good [8, 28], suggesting that within a single study group it is possible to construct a highly accurate classifier to differentiate OSCC from normal. The issue of tumor etiology causing distinct patterns of RNA expression has also been explored. Human papilla virus (HPV)-expressing squamous cell carcinomas of the oral pharynx may indeed have distinct RNA profiles [24–26] so we mainly focus in this review on OSCC, which is almost always free of transforming HPV [24]. A further investigation of tumor etiology reveals little effect from tobacco exposure on miRNA or mRNA expression in OSCC [25, 29]. However, it is not clear if the same is true for betel nut exposure, which may contribute to variability between studies.

Table 1.

Sources of variability in identifying a miRNA signature for HNSCC and OSCC with surgically obtained tissue samples

| Type | Comments/Solution |

|---|---|

| Statistical [17] | Use statistical analysis that avoids overfitting data |

| miRNA measuring platform [21] | Improvements in miRNA measurement with the usage of RT-PCR & NGS but still must be considered as an error source |

| Differences in etiology [23–25, 27] | Tobacco vs. betel vs. HPV vs. unknown. It is not known if betel usage produces OSCC with a distinct RNA profile. Tobacco does not, HPV does. |

| Intertumor heterogeneity in RNA expression [23–25, 27] | Not a major problem for OSCC |

| Tumor localization [8, 26] | HNSCC can vary by site so focus on OSCC |

|

Low sample number [25] Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2015) |

Small subject size may limit accuracy, large sample numbers available from the TCGA study |

| Tissue dissection [1] |

|

Heterogeneous Tissue in Tumor Samples Leads to Difficulty in RNA-Based Diagnosis

The major source of the problems that have long been seen in RNA-based OSCC class prediction may be the variability in sample dissection within studies and between studies. Problems arise when RNA markers defined in one study are tested for classification of tumor samples from a different study, as has been observed [1]. Differences in platforms used to measure RNA can contribute to error, but another problem often overlooked may cause even more. While the tumor itself is epithelium, there can be variable amounts of stroma in samples. RNAs that are highly expressed in stroma but not in epithelium will obscure changes that occur in tumor epithelium. Descriptions of acceptable levels of stromal tissue in tumor samples are varied between studies, if present at all. The TCGA head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) study indicated that when sample acquisition is uniform, differentiation of normal versus malignant based on RNA is extremely accurate [25, 27]. When we tested marker RNAs identified by Lager et al. for European OSCC, mainly tobacco users, versus those miRNAs measured in the TCGA study, over 30 percent were no longer differentially expressed [8, 25]. In a study by Gombos et al. on 40 OSCC and 40 normal tissue controls, done in Europe, 4 miRNAs were shown to be differentially expressed at least 100% [28]. When we examined expression of these miRNAs in the TCGA dataset only one showed differential expression over 50% [25]. Perhaps because of this, only one microRNA, mir-21-5p, has been shown to be elevated in almost every study on OSCC or HNSCC [8, 25, 28, 30, 31]. Notably, mir-21-5p is expressed at high levels in epithelium and stroma, and is known to be further elevated in both tumor epithelium and the surrounding stroma. Thus, for mir-21-5p measurement, the presence of stroma may not be so important. Interestingly, in the study reported by Gombos et al. 4 miRNAs individually served as markers of OSCC with approximately 90% accuracy [28]. Remarkably when we tested them as a group for tumor classification of the TCGA sample set we found 92% accuracy [25]. However, accuracy of the classifier created using the recommended markers was largely dependent on mir-21-5p levels. When it was eliminated as a marker and the three remaining miRNAs, miR-221, miR-191, and miR-226, were used, accuracy slipped to 75%. We believe these results display the difficulty in applying results from one study to another. While other explanations are possible, we believe that the difficulty in achieving uniform tissue dissection between different research studies is a major factor. A second source of error is the variability in the amount of normal epithelium mixed in with the tumor epithelium, though this may be minimized by cancer field effects [32]. Nevertheless, this source of error makes it difficult to find RNAs that decrease in tumor since normal brush biopsy samples are 100% normal but malignant samples are a mix. Both of these sources of error can be limited by careful reproducible dissection of tumor samples as in the TCGA study where all tumor samples from which RNA was taken contained at least 60% tumor. In the TCGA study, laser capture microdissection of samples was done to insure this, a method at this time too cumbersome to do routinely [25].

Brush Biopsy Offers Tumor Samples that are Homogeneous Epithelium

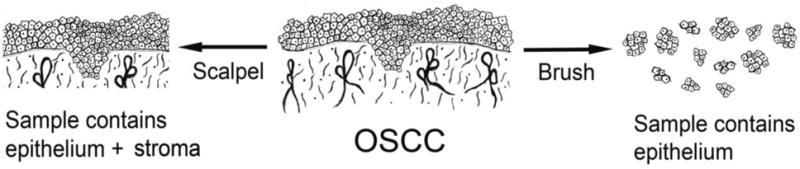

Brush biopsy, or related scraper-based methods, offer a noninvasive method of acquisition of cells and RNA from the epithelium of the oral mucosa as represented in figure 1 and reviewed earlier [33]. Sampling at sites within lesions that are not ulcerated, non-necrotic and minimally friable makes the samples nearly pure epithelium: keratinocytes plus a much smaller number of immune cells. For years this approach while informative about to OSCC characterization [34–37] has been limited by the variability of mRNA recovery with substantial numbers of samples having insufficient yield [29, 38, 39]. Quality is also generally lower than that of surgically obtained tissue making RT-PCR the most reliable method of measurement [40, 41]. The variable mRNA quality in brush biopsy samples is largely specific to squamous epithelium samples [41]. Spira’s group has shown that the brush samples from the psuedostratified columnar epithelium of the bronchi allow reproducible measurement of mRNA, which has resulted in a clinically used method to detect lung cancer [42, 43]. Much progress is also being made in the diagnosis of hard to detect bile duct malignancies, using brush-based sampling of mRNA from the simple cuboidal epithelium of the duct [44, 45]. A recent finding is that miRNA from oral squamous epithelium obtained by brush biopsy, unlike mRNA, is of high quality similar to miRNA in body fluid and paraffin-embedded tissue [10, 29, 46, 47]. miRNA profiles in individual brush biopsy OSCC samples show approximately 50% overlap with miRNA enriched in surgically obtained tumor tissue miRNA [29]. One hundred percent overlap was not expected as surgical samples contain varying amounts of stroma, which can express miRNAs at different levels than seen in epithelium proper. As described above, few miRNAs were observed to decrease in brush biopsy OSCC samples. This is likely due to the inclusion of normal epithelium in brush biopsy samples of smaller tumors, T1s and T2s. There is one other published study testing miRNA enriched in brush biopsy samples of OSCC [48]. Of the 12 miRNAs tested, 6 were tested in both studies and 3 showed the same statistically significant changes [29]. One might conclude that by removing stroma as a contaminant fewer samples are needed to produce a reproducible miRNA signature predictive of OSCC [27]. While the simple acquisition of nearly pure cells from the epithelium is a possible large advantage when using brush biopsy, there are insufficient studies to verify clinical application of this method to tumor diagnostics. Perhaps unexpectedly, the presence of multiple and distinct cell layers in squamous epithelium, and differential acquisition by the brush, has not prevented its accuracy in characterizing OSCC epithelial miRNA [29, 48, 49].

Figure 1.

Schematic of early OSCC shows tumor epithelium made of epithelial cells invading stroma, which contains fibroblasts, endothelial cells and immune cells, among others. Surgical acquisition of tumor tissue provides epithelium and stroma, while brush biopsy provides epithelial cells.

Changes in Body Fluid miRNA with OSCC Resemble Those Seen in Brush Biopsy Samples of OSCC

A third method to characterize HNSCC or oral tumors is by measurement of RNA, particularly miRNA, in body fluids [11, 30, 50–52]. While saliva is an obvious source of HNSCC RNAs [53–57], they can also be detected in serum and plasma [58–64]. As shown here in Table 2 and as reviewed by others, a number of miRNAs are elevated in body fluid in the presence of OSCC. These tests have shown some variability in RNA markers associated with OSCC or HNSCC but hold much potential [11, 51, 65]. Sources of error have slowed the identification of miRNA markers of OSCC and other cancers in body fluids. These include difficulty in identifying suitable internal controls for RNA levels in each sample, which is a major problem, low RNA concentration, and difficulty in RNA recovery, though steps are being made to resolve these issues [66, 67]. In the case of OSCC there is little knowledge of the source of these RNAs in body fluids, whether they come from shed cells, cellular secretions, etc. [46, 50]. We have found substantial agreement in OSCC miRNA markers identified in brush biopsy and body fluid samples in several studies [27]. Table 2 shows this finding. Most notable is the agreement with the work of Maclellan et al. who examined serum miRNAs in cases of OSCC and Zhou et al. who acquired samples by brush biopsy of tumor but used the same platform to measure miRNA, removing that as a source of variation [27, 64]. Of 10 miRNAs upregulated with p < 1 × 10–7 in serum, 8 were tested in an independent study of brush biopsy miRNA from OSCC and 6 were shown to be similarly enriched (75% agreement) [64]. This would favor a model where RNAs that change with OSCC formation are nonselectively secreted into blood from tumor or are from shedding of tumor cells that then lyse in the blood [68]. The elevated level of epithelial cells seen in blood from patients with tumors [69] and the ease in dislodging cells from tumors with a brush also suggest tumor cell shedding and/or leakage as source of body fluid miRNA. It is not clear if stromal cells undergo this process. Over all, this supports the utility of using brush biopsy as a surrogate to identify miRNA that have high potential to be enriched in plasma, serum, and saliva. Thus the same miRNA-based classifier for OSCC developed with brush biopsy samples may share many RNAs with those detected in body fluid. This is important as measurement of low concentration of miRNAs becomes easier, and more standardized in regard to optimized methods of measurement, selection of internal standards and data normalization [11, 65], body fluid-based miRNA quantification may be the most useful for OSCC detection as it can be done without lesion detection.

Table 2.

OSCC differentially expressed miRNAs collected from plasma/serum. Bold miRNAs are also enriched in brush biopsy samples. Arrows indicate miRNAs that decrease in level in OSCC patients, unmarked miRNAs indicate an increase

| Publication | Year | miRNAs | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| MacLellan | 2012 | miR-16, miR-26a, miR-17, miR-19a, miR-486-5p, miR-7, miR-30e, Let-7b, miR-92a, miR-25, Let-7a, miR-195, miR-624, miR-29a↓, miR-338-3p, miR↓-223↓, miR-142-5p↓, Let-7d↓ | Exiqon PCR |

| Hung | 2013 | miR-146a | TaqMan PCR |

| Lu | 2012 | miR-10b | TaqMan PCR |

| Liu | 2010 | miR-31 | TaqMan PCR |

Prognosis of OSCC Based on miRNAs in Surgically Obtained Tissue

Usage of RNA classifiers for tumor prognosis and to predict treatment outcomes is of great interest. Treatment planning today is based largely on tumor size and the presence and pattern of lymph node invasion [70–72]. Small tumors without lymph node invasion are treated typically with just surgery while small tumors with lymph node invasion and all large tumors are treated with surgery plus radiation and/or chemotherapy [73]. There is little customization of treatment for each patient. This is in contrast with what happens with estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer patients [14]. It is known that patients with breast tumors with a high cell proliferation index benefit from long-term cancer chemotherapy. Unfortunately, cell proliferation indices in breast tumors are difficult to measure reproducibly using immunohistochemistry. For that reason RNA tests based in part on expression of cell proliferation-linked genes, Oncotype Dx, Mammaprint, and PAM50, have filled this void and are routinely used for treatment planning for a large percentage of breast cancers [14]. This surgical based method relies on gene expression measurement of a specific group of genes involved in cell proliferation which we expect to be elevated in epithelium versus most other cell types and more so in tumor. While these methods are not extremely accurate, and showed 30% discordance when used on the same patients, they are a large improvement over the former methods of prediction of treatment outcome based on tumor size and stage, which did not correlate with outcome. Similarly, for OSCC it has been known for some time that there are a number of other histologic characteristics indicative of tumor aggressiveness. One of these, extracapsular spread of tumor outside the lymph node, adds to prognosis while others, including perineural invasion by the tumor into neural structures, tumor grade, pattern of tumor invasion, etc, have promise but are less accepted for a variety of reasons [72, 74–76].

RNA- or DNA-based methods of tumor characterization could offer an improved prognostic for OSCC that is less invasive and less demanding than prognosis dependent on histology. However, work with identifying changing tissue levels of mRNAs associated with poor prognosis has gone on for well over 10 years but has yet to yield a clinically useful gene signature for OSCC [77, 78]. More recently, a number of groups have identified single miRNAs, or sets of miRNAs, that can be measured to try to detect lymph node metastasis or tumors that are likely to show poor survival [9, 31, 79–88]. An immediate concern is that in studies where changes in miRNA marker levels are reported, those changes are often quite small, less than 100%. This would demand great accuracy in marker measurement. Overall, there are few examples of markers of poor prognosis being reported more than one time, suggesting the markers would not survive external validation. As an example, Severino et al. reported several markers of aggressive tumors that showed lymph node invasion [83]. In their work they compared small tumors with lymph node invasion versus large tumors without. An examination of the TCGA dataset of oral tumors shows that when the same comparison is made there is little change in expression of these miRNAs. This is not to say that these miRNAs are not involved in tumor aggressiveness, but that the difference is not useful diagnostically. Recently, using large datasets, two groups have established prognostic RNA-based classifiers for OSCC using 4 miRNAs and for HNSCC using 6 miRNAs [84, 86]. We note that of the excess of 25 miRNAs reported in earlier studies to be relevant to HNSCC and OSCC prognosis prediction only one, mir-218-5p, is in the newly identified OSCC classifier and one, miR-125b-2, in the new HNSCC classifier. Of greater concern is that in the study where the information is provided, the changes in miRNA marker levels between the high risk (short overall survival) versus low risk (long overall survival) are slight, 19% to 43% [86]. Thus usage of the measurement of levels of these markers to predict prognosis would require extreme accuracy in miRNA measurement for usage in the clinic. Once again an exception to this scenario is notable: mir-21-5p, which has shown increased expression in both stroma and tumor epithelium proper with OSCC, is also a marker for poor survival among HNSCC patients. It shows large scale increases in level in OSCC with shorter survival times [9, 31, 81, 82, 89, 90]. This reinforces the idea that sample purity may play a major role in marker utility for detection and prognosis.

Conclusion

We would propose the counterintuitive idea that collection of tumor cells by scalpel or punch is not the ideal and that other methods, like brush biopsy, may provide near homogenous epithelium and thus give a better starting point for material for tumor detection and prognosis. If body fluid miRNA similarly is chiefly composed of miRNA from shed or lysed cells or secreted tumor epithelial RNA in OSCC patients [68, 69] then it may show a similar superiority to measuring markers in surgically obtained tumor tissue [11]. Until a method for tumor microdissection that is rapid, fully automated and affordable exists, the advantages of brush and liquid biopsy are many.

Table 3.

OSCC differentially expressed miRNAs collected from saliva. Bold miRNAs are also enriched in brush biopsy samples. Arrows indicate miRNAs that decrease in level in OSCC patients, unmarked miRNAs indicate an increase

| Publication | Year | miRNAs | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salazar | 2014 | miR-9, miR-127, miR-191, miR-222, miR-134↓ | miScript PCR Qiagen |

| Park | 2009 | miR-125a, miR-200a | TaqMan PCR |

| Hung | 2016 | miR-31, miR-21 | TaqMan PCR |

| Liu | 2010 | miR-31 | TaqMan PCR |

| Zahran | 2015 | miR-21, miR-184, miR-145↓ | miScript PCR Qiagen |

| Momen-Heravi | 2014 | miR-136↓, miR-147↓, miR-1250↓, miR-148a↓, miR-632↓, miR-646↓, miR-668↓, miR-877↓, miR-503↓, miR-220a↓, miR-323-5p↓, miR-24, miR-27b | TaqMan PCR |

Highlights.

RNA based tumor detection in surgical tissue has not worked well for oral cancer

Brush biopsy of oral cancer provides RNA from epithelium cells in one step

Oral cancer-associated blood RNAs are largely from tumor

Examination of brush biopsy or body fluid RNA may allow oral cancer diagnosis

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The work by the lead author was funded in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute R21CA139137-01 and R03CA150076-01A1; and a subaward to the University of Illinois at Chicago STTR grant IIP-1346486 to Arphion Ltd. from the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a financial conflict of interest to report. Though we note some of the work cited in this review article, which was done by G. Adami, was funded by a subaward to the University of Illinois at Chicago from a National Science Foundation STTR grant awarded to Arphion Ltd for 2014.

Author Contributions

G. Adami contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, or interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. J. Tang contributed to data analysis and drafted the manuscript. M. Markiewicz contributed to data analysis and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Choi P, Chen C. Genetic expression profiles and biologic pathway alterations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1113–28. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu YH, Kuo HK, Chang KW. The evolving transcriptome of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Plos One. 2008;3:e3215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li G, Li X, Yang M, Xu L, Deng S, Ran L. Prediction of biomarkers of oral squamous cell carcinoma using microarray technology. Scientific reports. 2017;7:42105. doi: 10.1038/srep42105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JJ, Hung HC, Cheng SJ, Chiang CP, Liu BY, Yu CH, et al. Factors associated with underdiagnosis from incisional biopsy of oral leukoplakic lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendez E, Cheng C, Farwell DG, Ricks S, Agoff SN, Futran ND, et al. Transcriptional expression profiles of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer. 2002;95:1482–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Mendez E, Houck J, Fan WH, Lohavanichbutr P, Doody D, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies genes predictive of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2008;17:2152–62. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziober AF, Patel KR, Alawi F, Gimotty P, Weber RS, Feldman MM, et al. Identification of a gene signature for rapid screening of oral spuamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5960–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lajer CB, Nielsen FC, Friis-Hansen L, Norrild B, Borup R, Garnaes E, et al. Different miRNA signatures of oral and pharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas: a prospective translational study. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:830–40. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamali Z, Asl Aminabadi N, Attaran R, Pournagiazar F, Ghertasi Oskouei S, Ahmadpour F. MicroRNAs as prognostic molecular signatures in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:321–31. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John K, Wu J, Lee BW, Farah CS. MicroRNAs in Head and Neck Cancer. Int J Dent. 2013;2013:650218. doi: 10.1155/2013/650218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin N, Lin Y, Fu X, Wu C, Xu J, Cui Z, et al. MicroRNAs as a Novel Class of Diagnostic Biomarkers in Detection of Oral Carcinoma: a Meta-Analysis Study. Clin Lab. 2016;62:451–61. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2015.150802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishino M. Molecular cytopathology for thyroid nodules: A review of methodology and test performance. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:14–27. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moschini M, Spahn M, Mattei A, Cheville J, Karnes RJ. Incorporation of tissue-based genomic biomarkers into localized prostate cancer clinics. Bmc Med. 2016;14:67. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0613-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyorffy B, Hatzis C, Sanft T, Hofstatter E, Aktas B, Pusztai L. Multigene prognostic tests in breast cancer: past, present, future. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:11. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0514-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sotiriou C, Wirapati P, Loi S, Harris A, Fox S, Smeds J, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: Understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J Natl Cancer I. 2006;98:262–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupuy A, Simon RM. Critical review of published microarray studies for cnacer outcome and guidelines on statistical analysis and reporting. J Nat Cancer Institute. 2007;99:147–57. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon R. Development and evaluation of therapetuically relevant predictive classifier using gene expression profiling. J Nat Cancer Institute. 2006;98:1169–71. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagadia R, Pandit P, Coman WB, Cooper-White J, Punyadeera C. miRNAs in head and neck cancer revisited. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2013;36:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13402-012-0122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baras AS, Mitchell CJ, Myers JR, Gupta S, Weng LC, Ashton JM, et al. miRge - A Multiplexed Method of Processing Small RNA-Seq Data to Determine MicroRNA Entropy. Plos One. 2015;10:e0143066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mestdagh P, Hartmann N, Baeriswyl L, Andreasen D, Bernard N, Chen CF, et al. Evaluation of quantitative miRNA expression platforms in the microRNA quality control (miRQC) study (vol 11, pg 809, 2014) Nat Methods. 2014;11:971–71. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokowy T, Eszlinger M, Swierniak M, Fujarewicz K, Jarzab B, Paschke R, et al. Analysis options for high-throughput sequencing in miRNA expression profiling. BMC research notes. 2014;7:144. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung CH, Parker JS, Karaca G, Wu J, Funkhouser WK, Moore D, et al. Molecular classification of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas using patterns of gene expression. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter V, Yin X, Wilkerson MD, Cabanski CR, Zhao N, Du Y, et al. Molecular subtypes in head and neck cancer exhibit distinct patterns of chromosomal gain and loss of canonical cancer genes. Plos One. 2013;8:e56823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Network TCGA. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517:576–82. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Cecco L, Nicolau M, Giannoccaro M, Daidone MG, Bossi P, Locati L, et al. Head and neck cancer subtypes with biological and clinical relevance: Meta-analysis of gene-expression data. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9627–42. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Kolokythas A, Schwartz JL, Epstein JB, Adami GR. microRNA from brush biopsy to characterize oral squamous cell carcinoma epithelium. Cancer Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cam4.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gombos K, Horvath R, Szele E, Juhasz K, Gocze K, Somlai K, et al. miRNA expression profiles of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:1511–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolokythas A, Zhou Y, Schwartz JL, Adami GR. Similar Squamous Cell Carcinoma Epithelium microRNA Expression in Never Smokers and Ever Smokers. Plos One. 2015;10:e0141695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min AJ, Zhu C, Peng SP, Rajthala S, Costea DE, Sapkota D. MicroRNAs as Important Players and Biomarkers in Oral Carcinogenesis. Biomed Res Int. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/186904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hedback N, Jensen DH, Specht L, Fiehn AM, Therkildsen MH, Friis-Hansen L, et al. MiR-21 expression in the tumor stroma of oral squamous cell carcinoma: an independent biomarker of disease free survival. Plos One. 2014;9:e95193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angadi PV, Patil PV, Kale AD, Hallikerimath S, Babji D. Myofibroblast presence in apparently normal mucosa adjacent to oral squamous cell carcinoma associated with chronic tobacco/areca nut use: evidence for field cancerization. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72:502–08. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2013.871648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adami GR, Adami AJ. Looking in the mouth for noninvasive gene expression-based methods to detect oral, oropharyngeal, and systemic cancer. ISRN Oncol. 2012;2012:931301. doi: 10.5402/2012/931301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driemel O, Kosmehl H, Rosenhahn J, Berndt A, Reichert TE, Zardi L, et al. Expression analysis of extracellular matrix components in brush biopsies of oral lesions. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1565–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolokythas A, Schwartz JL, Pytynia KB, Panda S, Yao M, Homann B, et al. Analysis of RNA from brush cytology detects changes in B2M, CYP1B1 and KRT17 levels with OSCC in tobacco users. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:532–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz JL, Panda S, Beam C, Bach LE, Adami GR. RNA from brush oral cytology to measure squamous cell carcinoma gene expression. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:70–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toyoshima T, Koch F, Kaemmerer P, Vairaktaris E, Al-Nawas B, Wagner W. Expression of cytokeratin 17 mRNA in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells obtained by brush biopsy: preliminary results. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:530–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spira A, Beane J, Schembri F, Liu G, Ding CM, Gilman S, et al. Noninvasive method for obtaining RNA from buccal mucosa epithelial cells for gene expression profiling. Biotechniques. 2004;36:484–+. doi: 10.2144/04363RN03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spivack SD, Hurteau GJ, Jain R, Kumar SV, Aldous KM, Gierthy JF, et al. Gene-environment interaction signatures by quantitative mRNA profiling in exfoliated buccal mucosal cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6805–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kupfer DM, White VL, Jenkins MC, Burian D. Examining smoking-induced differential gene expression changes in buccal mucosa. Bmc Med Genomics. 2010;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sridhar S, Schembri F, Zeskind J, Shah V, Gustafson AM, Steiling K, et al. Smoking-induced gene expression changes in the bronchial airway are reflected in nasal and buccal epithelium. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferguson JS, Van Wert R, Choi Y, Rosenbluth MJ, Smith KP, Huang J, et al. Impact of a bronchial genomic classifier on clinical decision making in patients undergoing diagnostic evaluation for lung cancer. Bmc Pulm Med. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0217-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silvestri GA, Vachani A, Whitney D, Elashoff M, Smith KP, Ferguson JS, et al. A Bronchial Genomic Classifier for the Diagnostic Evaluation of Lung Cancer. New Engl J Med. 2015;373:243–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim TH, Chang JH, Lee HJ, Kim JA, Lim YS, Kim CW, et al. mRNA expression of CDH3, IGF2BP3, and BIRC5 in biliary brush cytology specimens is a useful adjunctive tool of cytology for the diagnosis of malignant biliary stricture. Medicine. 2016;95 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nischalke HD, Schmitz V, Luda C, Aldenhoff K, Berger C, Feldmann G, et al. Detection of IGF2BP3, HOXB7, and NEK2 mRNA Expression in Brush Cytology Specimens as a New Diagnostic Tool in Patients with Biliary Strictures. Plos One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng GF. Circulating miRNAs: Roles in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2015;81:75–93. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wali RK, Hensing TA, Ray DW, Dela Cruz M, Tiwari AK, Radosevich A, et al. Buccal microRNA dysregulation in lung field carcinogenesis: gender-specific implications. Int J Oncol. 2014;45:1209–15. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He Q, Chen Z, Cabay RJ, Zhang L, Luan X, Chen D, et al. microRNA-21 and microRNA-375 from oral cytology as biomarkers for oral tongue cancer detection. Oral Oncol. 2016;57:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kujan O, Desai M, Sargent A, Bailey A, Turner A, Sloan P. Potential applications of oral brush cytology with liquid-based technology: results from a cohort of normal oral mucosa. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:810–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larrea E, Sole C, Manterola L, Goicoechea I, Armesto M, Arestin M, et al. New Concepts in Cancer Biomarkers: Circulating miRNAs in Liquid Biopsies. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17050627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian X, Chen Z, Shi S, Wang X, Wang W, Li N, et al. Clinical Diagnostic Implications of Body Fluid MiRNA in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1324. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorenchtein M, Poh CF, Saini R, Garnis C. MicroRNAs in an oral cancer context - from basic biology to clinical utility. Journal of dental research. 2012;91:440–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034511431261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu CJ, Lin SC, Yang CC, Cheng HW, Chang KW. Exploiting salivary miR-31 as a clinical biomarker of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34:219–24. doi: 10.1002/hed.21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Momen-Heravi F, Trachtenberg AJ, Kuo WP, Cheng YS. Genomewide Study of Salivary MicroRNAs for Detection of Oral Cancer. Journal of dental research. 2014;93:86S–93S. doi: 10.1177/0022034514531018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park NJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Henson BS, Kastratovic DA, Abemayor E, et al. Salivary microRNA: discovery, characterization, and clinical utility for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5473–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salazar C, Nagadia R, Pandit P, Cooper-White J, Banerjee N, Dimitrova N, et al. A novel saliva-based microRNA biomarker panel to detect head and neck cancers. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2014;37:331–8. doi: 10.1007/s13402-014-0188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zahran F, Ghalwash D, Shaker O, Al-Johani K, Scully C. Salivary microRNAs in oral cancer. Oral Dis. 2015;21:739–47. doi: 10.1111/odi.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu CM, Lin PM, Wang YM, Chen ZJ, Lin SF, Yang MY. Circulating miRNA is a novel marker for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:1933–42. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hung PS, Liu CJ, Chou CS, Kao SY, Yang CC, Chang KW, et al. miR-146a enhances the oncogenicity of oral carcinoma by concomitant targeting of the IRAK1, TRAF6 and NUMB genes. Plos One. 2013;8:e79926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin SC, Liu CJ, Lin JA, Chiang WF, Hung PS, Chang KW. miR-24 up-regulation in oral carcinoma: positive association from clinical and in vitro analysis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:204–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu CJ, Kao SY, Tu HF, Tsai MM, Chang KW, Lin SC. Increase of microRNA miR-31 level in plasma could be a potential marker of oral cancer. Oral Dis. 2010;16:360–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu CJ, Tsai MM, Tu HF, Lui MT, Cheng HW, Lin SC. miR-196a overexpression and miR-196a2 gene polymorphism are prognostic predictors of oral carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(Suppl 3):S406–14. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2618-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu YC, Chen YJ, Wang HM, Tsai CY, Chen WH, Huang YC, et al. Oncogenic function and early detection potential of miRNA-10b in oral cancer as identified by microRNA profiling. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:665–74. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maclellan SA, Lawson J, Baik J, Guillaud M, Poh CF, Garnis C. Differential expression of miRNAs in the serum of patients with high-risk oral lesions. Cancer Med. 2012;1:268–74. doi: 10.1002/cam4.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Troiano G, Boldrup L, Ardito F, Gu X, Lo Muzio L, Nylander K. Circulating miRNAs from blood, plasma or serum as promising clinical biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review of current findings. Oral Oncol. 2016;63:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kok MG, Halliani A, Moerland PD, Meijers JC, Creemers EE, Pinto-Sietsma SJ. Normalization panels for the reliable quantification of circulating microRNAs by RT-qPCR. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2015;29:3853–62. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-271312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marabita F, de Candia P, Torri A, Tegner J, Abrignani S, Rossi RL. Normalization of circulating microRNA expression data obtained by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2016;17:204–12. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. MicroRNA signatures of tumor-derived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet M, Connelly MC, Rao C, et al. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6897–904. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rikardsen OG, Bjerkli IH, Uhlin-Hansen L, Hadler-Olsen E, Steigen SE. Clinicopathological characteristics of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Northern Norway: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:103. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woolgar JA, Triantafyllou A. Pitfalls and procedures in the histopathological diagnosis of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma and a review of the role of pathology in prognosis. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:361–85. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woolgar JA, Triantafyllou A, Lewis JS, Jr, Hunt J, Williams MD, Takes RP, et al. Prognostic biological featrues in neck dissection specimens. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1581–92. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang SH, O’Sullivan B. Oral cancer: Current role of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2013;18:e233–40. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Binmadi NO, Basile JR. Perineural invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a discussion of significance and review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1005–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mermod M, Tolstonog G, Simon C, Monnier Y. Extracapsular spread in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2016;62:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Montebugnoli L, Gissi DB, Flamminio F, Gentile L, Dallera V, Leonardi E, et al. Clinicopathologic parameters related to recurrence and locoregional metastasis in 180 oral squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22:55–62. doi: 10.1177/1066896913511982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Polanska H, Raudenska M, Gumulec J, Sztalmachova M, Adam V, Kizek R, et al. Clinical significance of head and neck squamous cell cancer biomarkers. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:168–77. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reddy RB, Bhat AR, James BL, Govindan SV, Mathew R, Ravindra DR, et al. Meta-Analyses of Microarray Datasets Identifies ANO1 and FADD as Prognostic Markers of Head and Neck Cancer. Plos One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chang KW, Liu CJ, Chu TH, Cheng HW, Hung PS, Hu WY, et al. Association between high miR-211 microRNA expression and the poor prognosis of oral carcinoma. Journal of dental research. 2008;87:1063–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang F, Tang J, Zhuang X, Zhuang Y, Cheng W, Chen W, et al. MiR-196a promotes pancreatic cancer progression by targeting nuclear factor kappa-B-inhibitor alpha. Plos One. 2014;9:e87897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jung HM, Phillips BL, Patel RS, Cohen DM, Jakymiw A, Kong WW, et al. Keratinization-associated miR-7 and miR-21 regulate tumor suppressor reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs (RECK) in oral cancer. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29261–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.366518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li J, Huang H, Sun L, Yang M, Pan C, Chen W, et al. MiR-21 indicates poor prognosis in tongue squamous cell carcinomas as an apoptosis inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3998–4008. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Severino P, Oliveira LS, Andreghetto FM, Torres N, Curioni O, Cury PM, et al. Small RNAs in metastatic and non-metastatic oral squamous cell carcinoma. Bmc Med Genomics. 2015;8:31. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shi H, Chen J, Li Y, Li G, Zhong R, Du D, et al. Identification of a six microRNA signature as a novel potential prognostic biomarker in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:21579–90. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shiiba M, Shinozuka K, Saito K, Fushimi K, Kasamatsu A, Ogawara K, et al. MicroRNA-125b regulates proliferation and radioresistance of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1817–21. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wong N, Khwaja SS, Baker CM, Gay HA, Thorstad WL, Daly MD, et al. Prognostic microRNA signatures derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cam4.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xu Q, Sun Q, Zhang JJ, Yu JS, Chen WT, Zhang ZY. Downregulation of miR-153 contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis in human epithelial cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:539–49. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang CC, Hung PS, Wang PW, Liu CJ, Chu TH, Cheng HW, et al. miR-181 as a putative biomarker for lymph-node metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:397–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Avissar M, McClean MD, Kelsey KT, Marsit CJ. MicroRNA expression in head and neck cancer associates with alcohol consumption and survival. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2059–63. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hui AB, Lenarduzzi M, Krushel T, Waldron L, Pintilie M, Shi W, et al. Comprehensive MicroRNA profiling for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1129–39. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]