Abstract

Alcohol-use disorder (AUD) is a relapsing disorder associated with excessive ethanol consumption. Recent studies support the involvement of epigenetic mechanisms in the development of AUD. Studies carried out so far have focused on a few specific epigenetic modifications. The goal of this project was to investigate gene expression changes of epigenetic regulators that mediate a broad array of chromatin modifications after chronic alcohol exposure, chronic alcohol exposure followed by 8 h withdrawal, and chronic alcohol exposure followed by 21 days of abstinence in Withdrawal-Resistant (WSR) and Withdrawal Seizure-Prone (WSP) selected mouse lines.

We found that chronic vapor exposure to highly intoxicating levels of ethanol alters the expression of several chromatin remodeling genes measured by quantitative PCR array analyses. The identified effects were independent of selected lines, which, however, displayed baseline differences in epigenetic gene expression.

We reported dysregulation in the expression of genes involved in histone acetylation, deacetylation, lysine and arginine methylation and ubiquitination, and in DNA methylation during chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal, but not after 21 days of abstinence. Ethanol-induced changes are consistent with decreased histone acetylation and with decreased deposition of the permissive ubiquitination mark H2BK120ub, associated with reduced transcription. On the other hand, ethanol-induced changes in the expression of genes involved in histone lysine methylation are consistent with increased transcription. The net result of these modifications on gene expression is likely to depend on the combination of the specific histone tail modifications present at a given time on a given promoter.

Since alcohol does not modulate gene expression unidirectionally, it is not surprising that alcohol does not unidirectionally alter chromatin structure toward a closed or open state, as suggested by the results of this study.

Keywords: alcohol-use disorder, epigenetics, histone acetylation, histone lysine methylation, histone arginine acetylation, histone ubiquitination, DNA methylation

Introduction

Alcohol-use disorder (AUD) is one of the most common chronic relapsing diseases in the Western world. In general, the alcohol addiction cycle has been described as consisting of three stages: intoxication, withdrawal, and craving/abstinence (Koob and Volkow, 2010). Recently, the potential for involvement of changes in chromatin structure in alcohol abuse has been the focus of intensive research (Barbier et al., 2016; Finegersh et al., 2015; Gavin, Kusumo, Zhang, Guidotti, and Pandey, 2016; Mathies et al., 2015; Repunte-Canonigo et al., 2014; Schuebel, Gitik, Domschke, and Goldman, 2016).

The nucleosome is the fundamental subunit of chromatin structure and comprises 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around two copies of core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (Kornberg, 1977). Post-translational modifications (PTMs) to histone proteins and DNA methylation regulate chromatin architecture, affecting transcription factor binding to specific DNA sequences and ultimately gene expression (Badeaux and Shi, 2013). Many different histone PTMs have been described in the literature with the list increasing every year (Kouzarides, 2007; Mazzio and Soliman, 2012). Among the most ephemeral histone PTMs are histone acetylation and histone phosphorylation, with turnover rates of several minutes (Barth & Imhof, 2010). However, histone acetylation and phosphorylation may facilitate the deposition or removal of more stable histone tail modifications (such as histone methylation), and therefore have the potential to affect long-term gene expression (Barth and Imhof, 2010). Both marks are generally associated with active transcription (Cheung et al., 2000; Clayton and Mahadevan, 2003; Crosio, Heitz, Allis, Borrelli, and Sassone-Corsi, 2003; Sterner and Berger, 2000).

Histone lysine methylation is associated with gene activation or repression depending on the site of methylation. Histone lysine methylation sites associated with active transcription are: H3K4, H3K36, and H3K79; histone lysine methylation sites associated with transcriptional repression are: H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20. Histone lysine methylation and de-methylation are catalyzed by lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and demethylases (KDM), respectively, which are highly specific for the lysine residues they methylate or demethylate as they usually modify a single lysine on a single histone (Black, Van Rechem, and Whetstine, 2012; Peter and Akbarian, 2011).

Histone tails can also be modified by methylation of arginine residues. Arginine methylation has been associated with activation and repression of gene transcription and is catalyzed by protein arginine methyl-transferases (PRMTs) (Bedford and Richard, 2005; Yang and Bedford, 2013).

Another histone PTM, ubiquitylation, requires the sequential activities of three classes of enzymes: ubiquitin activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3). The main forms of ubiquitinated histones in vertebrates are mono-ubiquitination of lysine 119 of histone H2A (H2AK119ub), associated with transcriptional repression and mono-ubiqutination of lysine 120 of histone H2B (H2BK120ub), associated with transcriptional activation (Cao and Yan, 2012; Meas and Mao, 2015).

DNA methylation, i.e., the covalent attachment of a methyl group to the 5′ position of a cytosine, is generally associated with transcriptional silencing. DNA methyltransferases DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B are responsible for DNA methylation. The gene silencing effects of DNA methylation are partly mediated by methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins (Fatemi and Wade, 2006; Roloff, Ropers, and Nuber, 2003). MBD proteins also provide a platform for the cross talk between histone PTMs and DNA methylation by forming complexes with histone proteins, histone methyltransferases, HDACs, and ATPase chromatin remodeling complexes (Mazzio and Soliman, 2012).

Chromatin and DNA modifying enzymes can be organized in larger chromatin-modifying complexes such as the Nucleosome Remodeling and Histone Deacetylation complex (Mi-2/NuRD), the polycomb repressive complex (PRC) PRC1, which mediates monoubiquitination of histone H2A Lys-119, and PRC2, which catalyzes trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) associated with transcriptional repression (DesJarlais and Tummino, 2016).

In this study, we employed qPCR arrays to investigate alcohol-induced changes in the expression of 165 genes encoding for proteins involved in the modulation of chromatin structure during alcohol exposure, withdrawal, and abstinence in Withdrawal Seizure-Resistant (WSR) and Withdrawal Seizure-Prone (WSP) mice. We focused on the prefrontal cortex (PFC), a brain region important for executive control and associated with cognitive dysfunction and damage in alcoholics (Zahr et al., 2010). The main focus of the study was to investigate the time course of the effects of alcohol on the expression of genes involved in chromatin remodeling. As a secondary goal, we investigated whether WSP and WSR mice, two lines selectively bred to diverge in withdrawal severity after chronic intoxication (Kosobud and Crabbe, 1986), would display differences in alcohol-induced changes in epigenetic mediator gene expression.

Although there is an emerging literature on the effects of alcohol on epigenetic mediators (Barbier et al., 2015, 2016; Cervera-Juanes, Wilhelm, Park, Grant, and Ferguson, 2016; Pandey, Ugale, Zhang, Tang, and Prakash, 2008; Ponomarev, Wang, Zhang, Harris, and Mayfield, 2012; Warnault, Darcq, Levine, Barak, and Ron, 2013), no study has systematically and comprehensively examined changes in the expression of genes encoding for chromatin modifying proteins after chronic alcohol exposure, alcohol withdrawal, and protracted abstinence.

Materials and methods

Animal models

Male WSP-1 and WSR-1 selected mouse lines derived by selective breeding for divergent withdrawal severity from genetically heterogeneous HS/Ibg mice (Kosobud and Crabbe, 1986) were maintained under a light/dark cycle with lights on at 6:00 AM and lights off at 6:00 PM, with water and Purina Lab Diet chow available ad libitum. Room temperatures were maintained at 22 ± 1 °C. All animal procedures were approved by the Portland Oregon VA Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed US National Institutes of Health animal welfare guidelines.

Time Course of ethanol exposure and Brain Harvest

Mice were made dependent upon ethanol using a method of vapor inhalation in chambers manufactured in-house, with modifications previously published (Beadles-Bohling and Wiren, 2006). Drug-naïve adult mice from selected generation 26 (filial generations G87–G134) were used. Ethanol exposure was initiated at 8:00 AM. On day 1, ethanol exposed mice were weighed, injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with ethanol at 1.5 g/kg and with 68.1 mg/kg pyrazole HCl (Pyr; an alcohol dehydrogenase inhibitor used to maintain constant blood ethanol levels). Control animals were placed into air chambers and received Pyr only; a saline-only air control was not included because previous data have shown there is no difference between saline- and Pyr-treated animals with respect to broad profiles of gene expression analyzed by mRNA differential display (Schafer, Crabbe, and Wiren, 1998). All mice again received Pyr (68.1 mg/kg) at 24 h and 48 h to reduce fluctuations in blood ethanol concentration (BEC). Ethanol-exposed mice had 20 μL of blood taken from the tail for daily BEC determination. Following 72 h of ethanol vapor exposure, all mice were removed from the chambers, weighed, and had tail blood samples drawn for BEC determination by gas chromatography as previously described (Beadles-Bohling and Wiren, 2006). Brain tissue was harvested for RNA analysis from animals immediately after ethanol exposure (EXP-t0), 8 h after ethanol exposure, corresponding to peak withdrawal (WD-8h), and 21 days after alcohol exposure (abstinence; ABS-21d). PFC was isolated by dissection from whole brain by first discarding the olfactory bulb and making a coronal slice 2 mm into the frontal region of the cortex. Lateral regions were removed by cutting the tissue at a 45°angle with the lobes facing upward. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until processing. All animals used in these experiments were purposely not scored for handling-induced convulsions (HICs), to limit the effects of withdrawal seizures on gene expression. During withdrawal these mice typically show decreased activity, dysphoria, and, in some cases, mild tremor but do not show convulsions without handling.

RNA Isolation and targeted qPCR array analysis

Total RNA was isolated using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc.; Friendswood, TX) and genomic DNA was removed using DNA-Free RNA kit (Zymo Research; Irvine, CA) as previously described (Hashimoto, Forquer, Tanchuck, Finn, and Wiren, 2011; Hashimoto and Wiren, 2008). First strand synthesis was carried out with 1 μg of RNA using the RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with a Bio-Rad CFX96 using the “Mouse Epigenetic Chromatin Modification Enzymes” and the “Mouse Epigenetic Chromatin Remodeling Factors” qPCR Arrays (Qiagen). A total of 88 qPCR arrays were run with 3–4 biological replicates for each line (WSP & WSR) and treatment (control and ethanol). Quantitative PCR arrays have been successfully used by our laboratory and were proven to provide reliable data that do not require further confirmation; indeed, we previously validated the results on qPCR arrays and always found 100% reproducibility of these data when using traditional qPCR methods testing expression of individual genes (Wheeler et al., 2009; Wilhelm et al., 2015; Wiren, Semirale, Hashimoto, and Zhang, 2010).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using R, Prism v6.07 (GraphPad Software, Inc.; San Diego, CA), and SYSTAT 11 (SYSTAT Software Inc.; Point Richmond, CA). Differences of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Genes for normalization were identified by the geNorm method using the R package “NormqPCR” (Perkins et al., 2012) at each time point, and the geometric mean of the normalizing genes was calculated for each sample/array and used for ΔΔCt relative expression normalization. The geNorm approach identifies the most stable reference genes in a step-wise fashion and reduces reliance on traditional “housekeeping” genes. Five genes, identified by the approach described above, were used for normalization for each time point and array platform. Significant ethanol regulation was determined by ANOVA and t tests run in R using the “qvalue” (Storey, 2015) package to correct for multiple comparisons. The following two-way ANOVA analyses of qPCR results were carried out to determine treatment × line interactions: Comparison 1: Control-t0/WSP; EXP-t0/WSP; Control-t0/WSR; EXP-t0/WSR; Comparison 2: Control-8h/WSP; WD-8h/WSP; Control-8h/WSR; WD-8h/WSR; Comparison 3: Control-21d/WSP; ABS-21d/WSP; Control-21d/WSR; ABS-21d/WSR (Supplemental Tables 1, 2, 3). Data shown in Table 2 and Figs. 1 and 2 were analyzed by one-way ANOVA analyses at each time point after collapsing data derived from WSP and WSR lines. Data shown in Table 3, comparing alcohol-naïve WSR and WSP mice at the 21-day time point were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Heat maps and hierarchical clustering were created using the R package “ggplot2” with complete linkage for clustering. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Weight changes during ethanol exposure experiments were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (treatment × selected line). BECs during ethanol exposure were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (time point × selected line).

Table 2.

Ethanol-regulated genes involved in chromatin structure modification after exposure, withdrawal, and abstinence.*

| Symbol | GID | Exposure | Withdrawal | Abstinence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOH/Con | q value | EtOH/Con | q value | EtOH/Con | q value | ||

| Esco2 | 71988 | −1.093 | 0.2812 | −3.475 | 0.0081 | −1.737 | 0.5941 |

| Mbd4 | 17193 | −1.134 | 0.0408 | −1.394 | 0.0011 | −1.020 | 0.9893 |

| Phf7 | 71838 | −1.247 | 0.0032 | −1.391 | 0.0108 | −2.139 | 0.9518 |

| Hat1 | 107435 | −1.221 | 0.0021 | −1.377 | 0.0015 | 1.058 | 0.9764 |

| Smyd3 | 69726 | −1.177 | 0.0413 | −1.370 | 0.0069 | −1.156 | 0.9518 |

| Dnmt1 | 13433 | −1.091 | 0.1204 | −1.321 | 0.0007 | 1.032 | 0.9518 |

| Setd6 | 66083 | −1.114 | 0.0303 | −1.229 | 0.0055 | −1.021 | 0.9518 |

| Setdb1 | 84505 | −1.051 | 0.0025 | −1.227 | 0.0379 | 1.029 | 0.9518 |

| Baz2b | 407823 | −1.166 | 0.0139 | −1.226 | 0.0041 | 1.119 | 0.4758 |

| Prmt7 | 214572 | −1.106 | 0.0021 | −1.211 | 0.0108 | 1.024 | 0.9017 |

| Bptf | 207165 | −1.030 | 0.2195 | −1.199 | 0.0007 | 1.003 | 0.9893 |

| Kat6b | 54169 | −1.028 | 0.2385 | −1.184 | 0.0012 | −1.028 | 0.9518 |

| Ube2a | 22209 | −1.092 | 0.0021 | −1.184 | 0.0109 | 1.068 | 0.9359 |

| Ing1 | 26356 | −1.058 | 0.1443 | −1.181 | 0.0009 | 1.118 | 0.5941 |

| Atf2 | 11909 | −1.074 | 0.0328 | −1.167 | 0.0083 | 1.018 | 0.9764 |

| Pcgf6 | 71041 | 1.000 | 0.3285 | −1.166 | 0.0076 | 1.042 | 0.9518 |

| Phf6 | 70998 | −1.009 | 0.2708 | −1.163 | 0.0011 | 1.094 | 0.7409 |

| Prmt5 | 27374 | −1.038 | 0.1713 | −1.152 | 0.0011 | −1.006 | 0.9893 |

| Ezh2 | 14056 | −1.023 | 0.2516 | −1.150 | 0.0099 | 1.049 | 0.9518 |

| Setd2 | 235626 | 1.017 | 0.2466 | −1.145 | 0.0074 | −1.018 | 0.9806 |

| Kat6a | 244349 | −1.065 | 0.1359 | −1.143 | 0.0081 | −1.029 | 0.9764 |

| Pcgf5 | 76073 | −1.041 | 0.1195 | −1.130 | 0.0055 | 1.086 | 0.5941 |

| Rnf20 | 109331 | −1.016 | 0.2605 | −1.130 | 0.0072 | −1.031 | 0.9764 |

| Suz12 | 52615 | 1.010 | 0.2768 | −1.085 | 0.0012 | 1.065 | 0.7823 |

| Esco1 | 77805 | −1.140 | 0.0021 | −1.077 | 0.0830 | 1.071 | 0.9518 |

| Ash1l | 192195 | 1.080 | 0.0082 | −1.067 | 0.1505 | −1.102 | 0.8389 |

| Setd3 | 52690 | 1.053 | 0.0021 | −1.002 | 0.4491 | 1.018 | 0.9764 |

| Prmt1 | 15469 | −1.178 | 0.0032 | 1.014 | 0.2640 | −1.074 | 0.9017 |

| Hdac3 | 15183 | 1.078 | 0.0062 | 1.039 | 0.0992 | −1.044 | 0.9764 |

| Ing4 | 28019 | 1.142 | 0.0032 | 1.120 | 0.0303 | 1.004 | 0.9893 |

| Chd3 | 216848 | 1.088 | 0.0068 | 1.146 | 0.0813 | 1.060 | 0.9017 |

| Setd7 | 73251 | 1.120 | 0.0068 | 1.177 | 0.0074 | −1.019 | 0.9764 |

| Mbd3 | 17192 | 1.172 | 0.0008 | 1.213 | 0.0052 | 1.056 | 0.9017 |

| Brd2 | 14312 | 1.086 | 0.0113 | 1.216 | 0.0009 | −1.037 | 0.9518 |

| Prmt6 | 99890 | 1.104 | 0.0184 | 1.224 | 0.0007 | −1.142 | 0.5941 |

| Mta2 | 23942 | 1.032 | 0.2090 | 1.248 | 0.0015 | −1.027 | 0.9764 |

| Prmt8 | 381813 | 1.130 | 0.0685 | 1.250 | 0.0046 | 1.081 | 0.8936 |

| Mbd1 | 17190 | 1.088 | 0.0892 | 1.263 | 0.0052 | −1.002 | 0.9893 |

| Cbx4 | 12418 | 1.215 | 0.0105 | 1.294 | 0.0069 | 1.089 | 0.9518 |

| Dot1l | 208266 | −1.030 | 0.2576 | 1.376 | 0.0069 | −1.201 | 0.9017 |

| Zmynd8 | 228880 | 1.212 | 0.0109 | 1.400 | 0.0007 | −1.060 | 0.9518 |

| Cdyl2 | 75796 | 1.055 | 0.1931 | 1.432 | 0.0069 | −1.235 | 0.5941 |

| Nab2 | 17937 | −1.311 | 0.0198 | 1.751 | 0.0044 | −1.031 | 0.9806 |

The analysis was carried out on collapsed data from WSP and WSR, since no Line × Treatment differences were identified.

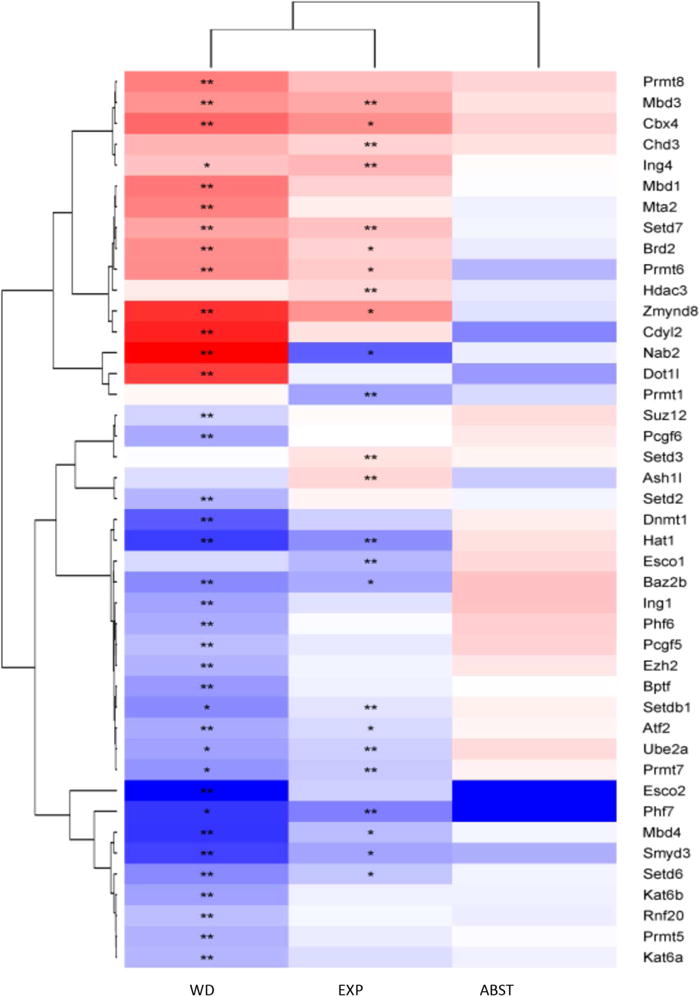

Fig. 1. Hierarchical clustering of expression differences in factors modifying chromatin structure after chronic ethanol exposure (EXP), chronic ethanol exposure followed by 8-h withdrawal (WD), and chronic ethanol exposure followed by 21 days of abstinence (ABS) shows similarity of response to ethanol at EXP and WD.

Genes identified as regulated by ethanol (main effect of treatment; q < 0.05, *; q < 0.01, **) were only identified at EXP and WD time points, and the expression pattern between EXP and WD were very similar. Each column in the heat-map represents the expression at each time, with red indicating up-regulation by ethanol and blue indicating down-regulation by ethanol. For each column, the selected line data (i.e., WSP and WSR) were collapsed, as we identified no significant line × treatment interactions (see Supplemental Tables 1, 2, and 3).

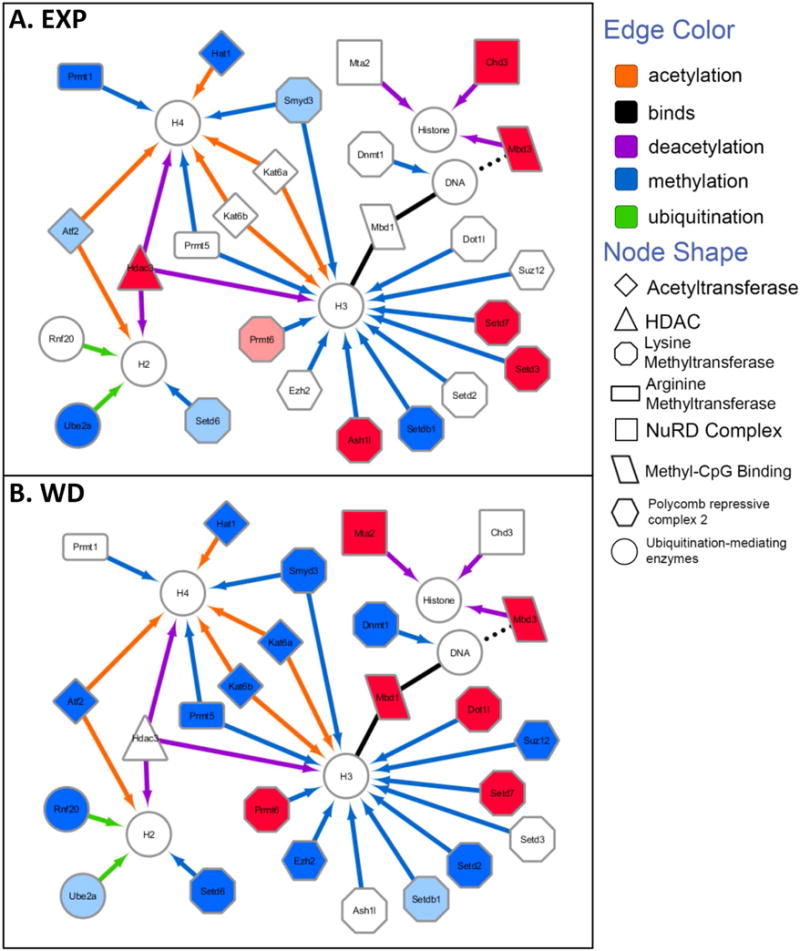

Fig. 2. Network of gene expression changes and their association to chromatin modifications after chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal.

Interaction networks of genes whose expression is significantly altered by ethanol at EXP and/or WD were created in Cytoscape 3.4 and organized based on the known chromatin modifications they target (designated by the edge color pointing to the affected histone or DNA structure) as well as on their molecular function (designated by the shape of the node). Upregulated expression in EXP or WD compared to their respective controls was designated by the colors pink (q < 0.05) or red (q < 0.01); downregulation of expression was designated by the colors azure (q < 0.05) or blue (q < 0.01).

Table 3.

Expression of genes involved in modifying chromatin structure significantly different in WSP and WSR mice at baseline.

| Symbol | GID | WSP ΔΔct | WSP ΔΔct | WSP/WSR | q value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kdm5c | 20591 | 0.111 | 0.209 | −1.875 | 0.0092 |

| Kat5 | 81601 | 0.585 | 0.702 | −1.202 | 0.0160 |

| Cbx3 | 12417 | 0.792 | 0.255 | 3.109 | 0.0160 |

| Kat6b | 54169 | 0.278 | 0.335 | −1.206 | 0.0256 |

| Suv39h1 | 20937 | 0.113 | 0.167 | −1.478 | 0.0256 |

| Rps6ka5 | 73086 | 0.126 | 0.249 | −1.985 | 0.0306 |

| Brpf3 | 268936 | 0.132 | 0.103 | 1.284 | 0.0306 |

| Kat6a | 244349 | 0.413 | 0.605 | −1.465 | 0.0332 |

| Csrp2bp | 228714 | 0.133 | 0.210 | −1.587 | 0.0473 |

| Hdac5 | 15184 | 0.335 | 0.573 | −1.708 | 0.0473 |

| Kdm1a | 99982 | 0.385 | 0.598 | −1.552 | 0.0473 |

| Kdm4c | 76804 | 0.218 | 0.297 | −1.362 | 0.0473 |

| Prmt1 | 15469 | 0.602 | 0.856 | −1.424 | 0.0473 |

| Prmt2 | 15468 | 1.017 | 0.771 | 1.318 | 0.0473 |

| Setdb1 | 84505 | 0.229 | 0.322 | −1.408 | 0.0473 |

| Suv420h1 | 225888 | 0.288 | 0.401 | −1.393 | 0.0473 |

| Usp21 | 30941 | 0.440 | 0.359 | 1.224 | 0.0473 |

| Whsc1 | 107823 | 0.041 | 0.075 | −1.820 | 0.0473 |

| Gapdh | 14433 | 13.825 | 17.341 | −1.254 | 0.0473 |

| Chd5 | 269610 | 0.623 | 0.549 | 1.134 | 0.0473 |

| Mll3 | 231051 | 0.260 | 0.390 | −1.499 | 0.0473 |

| Ezh2 | 14056 | 0.074 | 0.107 | −1.446 | 0.0473 |

Genes highlighted in yellow are also regulated by ethanol; genes underlined are the ones with higher baseline expression in WSP than in WSR.

Chemicals

Ethanol (ethyl alcohol, absolute, 200 proof) for use in chemical assays was purchased from AAPER Alcohol and Chemical (Shelbyville, KY), and Pharmco Products, Inc. (Brookfield, CT) for use in the ethanol vapor chambers and injections. Pyr was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in 0.9% saline (NaCl). Ethanol (20% v/v) was mixed with 0.9% saline and injected i.p. or introduced without mixing as a vapor into the chambers.

Results

Blood Alcohol Concentrations

Male WSP-1 and WSR-1 mice were 42–89 days old at the start of the experiments (70.3 ± 1.6). Average BECs over the 72-h exposure were in the highly intoxicated range and averaged 2.2 ± 0.07 mg/mL (47.7 mM). No significant main effects of selected line, time point, or their interaction (line × time) were found in a two-way ANOVA of BECs.

Analysis of Treatment × Line interactions after chronic ethanol exposure (EXP), chronic ethanol exposure followed by 8-h withdrawal (WD), and chronic ethanol exposure followed by 21 days abstinence (ABS) in WSP and WSR selected lines

We analyzed the effect of chronic ethanol exposure (EXP), of chronic ethanol exposure followed by 8h withdrawal (WD), and of chronic ethanol exposure followed by 21 days abstinence (ABS) on each of the 165 genes involved in modifying chromatin structure by two-way ANOVA. Each treatment group had its own time-matched control group: t0; 8 h; and 21 days (see Methods). Comparisons were carried out between groups within the same time point. We found no treatment (EXP; WD; or ABS) × line (WSP vs. WSR) interactions in any of the genes at any of the time points analyzed (t0; 8 h; and 21 days). These data are provided in Supplemental Tables 1, 2, and 3. Based on these results, we carried out further analyses in data collapsed across lines.

Chronic ethanol vapor exposure and ethanol withdrawal alter chromatin modifying gene expression

Table 1 reports the list of genes investigated in this study and the cellular function of their encoded proteins. Genes that were upregulated or downregulated by either EXP or WD are highlighted in pink and azure respectively; the only gene that is regulated in an opposite manner in EXP and WD (Nab2) is highlighted in green.

Table 1.

Genes involved in modulating chromatin structure analyzed in the present study

| DNA Methyltransferases: , Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b. |

| Acetyltransferases: , Cdyl, Ciita, Csrp2bp, , , , Kat2a, Kat2b (Gcn512), Kat5, Kat8 (Myst1), Kat7 (Myst2), , , Ncoa1, Ncoa3, Ncoa6. |

| Histone Methyltransferases: Carm1 (Prmt4), , Ehmt1, Ehmt2, Mll3, , Prmt2, Prmt3, , , , , Setdb2, Smyd1, , Suv39h1. |

| SET Domain Proteins (Histone Methyltransferase Activity): , Mll5, Nsd1, Setd1a, , , , Setd4, Setd5, , , Setd8, Setdb1, Suv420h1, Whsc1. |

| Histone Phosphorylation: Aurka, Aurkb, Aurkc, Nek6, Pak1, Rps6ka3, Rps6ka5. |

| Histone Ubiquitination: Dzip3, Mysm1, Rnf2*, , , Ube2b, Usp16, Usp21, Usp22. |

| DNA/Histone Demethylases: Kdm1a, Kdm5b, Kdm5c, Kdm4a, Kdm4c, Kdm6b. |

| Histone Deacetylases: Hdac1, Hdac2, , Hdac4, Hdac5, Hdac6, Hdac7, Hdac8, Hdac9, Hdac10, Hdac11. |

| SWI/SNF Complex Components (ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex): Arid1a, Arid2, Ino80 (Inoc1), Smarca2, Smarca4, Smarca5. |

| Polycomb Repressive Groups 1 and 2 (PRC1/2) components and associated proteins: Asxl1, Bmi1, Ctbp1, Ctbp2, Eed, , Pcgf1, Pcgf2, Pcgf3, , , Phc1, Phc2, Ring1**, Rnf2*, , Trim27 |

| Chromobox/Heterochromatin Protein 1 (HP1) Homologs: Cbx1, Cbx2, Cbx3, , Cbx5, Cbx6, Cbx7, Cbx8. |

| Bromodomain Proteins: Baz1a, Baz1b, Baz2a, , , Brd1, , Brd3, Brd4, Brd7, Brd8, Brdt, Brpf1, Brpf3, Brwd1, Brwd3, , Wdr11. |

| Chromodomain/Helicase/DNA-Binding Domain (CHD) Proteins: Cdyl, , Chd1, Chd2, , Chd4, Chd5, Chd6, Chd7, Chd8, Chd9. |

| Nucleosome-Remodeling and Histone Deacetylase (NuRD) Complex Components: Mta1, , , Spen, Chd3, ***. |

| Plant Homeodomain (PHD) Proteins: Nsd1, Phf1, Phf2, Phf3, Phf5a, , , Phf13, Phf21b. |

| Inhibitor of Growth (ING) Family Members: , Ing2, Ing3, , Ing5, Ring1**. |

| Methyl-CpG DNA Binding Domain (MDB) Proteins: , ***, , Mecp2, Hinfp. |

| CCCTC-Binding Factor (Zinc Finger Protein): Ctcf. |

Genes that are upregulated or downregulated by either EXP or WD are highlighted in pink or azure, respectively; the only gene that is regulated in opposite manner in EXP and WD (Nab2) is highlighted in green.

: genes that have been listed under 2 categories.

Table 2 summarizes all genes differentially expressed in EXP, WD, or ABS animals compared to their time-matched controls. Hierarchical cluster analysis of genes whose expression displays significant changes reveals a similar expression pattern at EXP and WD, while the ABS time point is substantially different (Fig. 1). A total of 43 genes were differentially expressed in ethanol-exposed animals compared to control animals under the EXP and/or WD conditions. At ABS, none of the examined genes displayed significant changes in expression relative to control. Twenty-five of these genes were differentially expressed in the EXP condition, 37 were changed in the WD condition, and 18 genes were regulated in both conditions, EXP and WD. Of the 18 genes in which changes were seen during WD and EXP, 17 displayed changes in the same direction; the expression of one gene (Nab2) was regulated in the opposite direction. Eighteen genes were regulated only at WD, while six genes were only regulated at EXP (Table 1). Together these observations indicate that ethanol and ethanol withdrawal affect genes encoding for proteins that bind and/or modify chromatin structure. The observation that the WD time point has the most changes indicates that ethanol withdrawal may have a bigger impact on chromatin structure than ethanol exposure.

Further analysis and discussion was limited to genes well characterized for their role in inducing histone PTMs and DNA methylation and associated with changes in gene transcription. Interaction networks were created (Fig. 2) of genes involved in histone acetylation/deacetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, and DNA methylation whose expression is significantly altered by ethanol at EXP and/or WD. Genes were organized based on the known chromatin modifications that are targeted by their encoded proteins (designated by the edge color pointing to the affected histone or DNA structure), as well their molecular function (designated by the shape of the node). Upregulated expression in EXP or WD compared to their respective controls was designated by the colors pink (q value < 0.05) or red (q value < 0.01). Downregulated expression was designated by the colors azure (q value < 0.05) or blue (q value < 0.01).

Alcohol exposure and withdrawal downregulate the expression of genes involved in histone acetylation and upregulate the expression of genes involved in histone deacetylation

A total of eight genes involved in histone acetylation were affected by alcohol. During EXP Hat1, encoding for histone acetyltransferase 1 (HAT1), which acetylates H4, and Atf2, encoding for activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2), which specifically acetylates H2B and H4, were downregulated. Furthermore, Hdac3, encoding for histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3), Mbd3, encoding for methyl-binding domain 3 (MBD3), and Chd3, encoding for the chromodomain 3 (CHD3) were upregulated. MBD3 and CHD3 are key components of the Nucleosome Remodeling and Histone Deacetylation (NuRD) complex involved in histone deacetylation.

During WD, in addition to Hat1 and Atf2, two other genes encoding histone lysine acetyltransferases were downregulated: Kat6A and Kat6B, encoding for two H3 and H4 histone lysine acetyltransferase, KAT6A and KAT6B (also known as MOZ and MORF, respectively). Two genes involved in deacetylation through the NuRD complex were upregulated: Mdb3 and Mta2.

Alcohol exposure and withdrawal alter the expression of 10 genes encoding for proteins involved in histone lysine methylation

Ten genes encoding for proteins involved in histone lysine methylation were regulated by EXP and/or WD. During EXP, three genes encoding for histone methyltransferases were downregulated: Smyd3, encoding for SET And MYND Domain Containing 3 (SMYD3), which di- and trimethylates H3K4; Setdb1, encoding for SET Domain Bifurcated 1 (SETDB1), which trimethylates H3K9; and Setd6, encoding for SET Domain Containing 6 (SETD6), which mono-methylates the lysine 8 on the histone variant H2AZ (H2AZK8me1). Three histone lysine methylation genes were upregulated during EXP: Setd7, encoding for SET domain containing 7 (SETD7), which specifically mono-methylates H3K4; Setd3, encoding for SETD3, which methylates H3K4 and H3K36; and Ash1l, encoding for (absent, small, or homeotic) protein 1-like (ASH1l), which methylates H3K36.

At WD, five genes encoding for proteins involved in histone lysine methylation were downregulated: Smyd3, Setdb1, and Setd2, encoding for SETD2, which specifically trimethylates H3K36; Ezh2, encoding for enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), the catalytic subunit of the repressive complex PRC2, which catalyzes the trimethylation of H3K27; and Suz12, encoding for another member of the PRC2 complex, suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12). At the same time point, two lysine methyltransferase genes were upregulated: Setd7, encoding for SETD7 which mono-methylates H3K4 and Dot1l encoding for DOT1-like protein (Dot1l), which methylates H3K79.

Alcohol exposure and withdrawal affect in opposite directions the expression of genes encoding for proteins involved in DNA methylation

Two genes involved in DNA methylation and in the binding of methylated DNA were affected only at WD. Dnmt1, encoding for DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1), was downregulated, while Mbd1, encoding for methyl-binding domain 1 (MBD1), was upregulated. Reduced Dnmt1 expression would be expected to be associated with increased euchromatin and transcription, while increased Mdb1 expression is associated with transcription repression.

Alcohol exposure and withdrawal affect the expression of genes encoding for proteins involved in histone arginine methylation

Protein arginine methyltransferase (PRMT) enzymes catalyze histone arginine methylation. PRMTs catalyze the transfer of one methyl group leading to the formation of monomethylarginine (MMA), or two methyl groups, generating asymmetric dimethylarginines (ADMA) or symmetric dimethylarginines (SDMA) (Bedford and Richard, 2005; Di Lorenzo and Bedford, 2011; Morales, Caceres, May, and Hevel, 2016; Yang and Bedford, 2013). Prmt1 is downregulated at EXP and encodes for the major asymmetric arginine methyltransferase, which specifically deposits an ADMA mark on histone H4 at arginine 3 (H4R3me2a), associated with transcription activation (Yang and Bedford, 2013). Prmt6 is upregulated at both EXP and WD, and encodes an enzyme primarily responsible for H3R2 asymmetric dimethylation (H3R2me2a), which is considered to act as a transcription repressor by preventing the deposition of the transcription activating mark H3K4me3 (Guccione et al., 2007). Prmt5 is downregulated during WD and encodes for the major symmetric arginine methyltransferase, which functions as a transcription repressor by depositing the repressive SDMA marks H3R8me2s and H4R3me2s (Yang and Bedford, 2013).

Ethanol downregulates the expression of two genes encoding for proteins involved in the ubiquitination of H2BK120, associated with transcriptional activation

Histone ubiquitination is also affected at WD and, to a lesser extent, at EXP. Two genes involved in histone ubiquitination are downregulated at WD: Rnf20 and Ube2a; Ube2a was also downregulated at EXP. Rnf20 encodes for ring finger protein 20 (RNF20), an E3 ubiquitin ligase; Ube2a encodes for ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2A (UBE2A), an E2 enzyme that works together with E3 enzymes such as RNF20 in the mono-ubiquitination of H2BK120. Ubiquitination of H2BK120 is associated with transcriptional activation as it modulates H3K4 and H3K79 di- and trimethylation (Cao and Yan, 2012; Meas and Mao, 2015). The decrease in expression of Rnf20 and Ube2a genes observed at WD and, for Ube2a, at EXP, is therefore consistent with silencing of gene expression.

Alcohol exposure and withdrawal do not affect the expression of genes encoding for proteins involved in histone phosphorylation and histone demethylation

Interestingly, genes involved in histone phosphorylation and histone demethylation were completely unaffected by ethanol.

Differences in baseline expression of epigenetic machinery regulating genes in WSR and WSP selected lines

We also analyzed differences in the baseline expression of genes regulating chromatin structure between WSP and WSR mice. For this analysis we used only control animals of the ABS group, since these animals, after being housed in vapor chambers for 72 h, were returned to their regular housing and remained untouched for 21 days.

Table 3 shows that 22 genes were expressed at different levels in WSP and WSR animals. Five of these genes were also found to be affected by ethanol. Eighteen of the differentially expressed genes were expressed at higher levels in WSR mice, while only four were expressed at higher levels in WSP.

Discussion

Our studies indicate that several genes regulating chromatin modifications are affected by chronic ethanol exposure (EXP), and even more genes are affected by chronic alcohol exposure followed by 8 h of ethanol withdrawal (WD). Ethanol-induced changes in the expression of genes involved in regulating chromatin structure are independent from the genetic background of the WSP and WSR mouse lines. EXP and WD modulated the expression of genes involved in most of the epigenetic processes investigated, namely histone acetylation and deacetylation, histone lysine methylation, histone arginine methylation, histone ubiquitination, and DNA methylation, while genes involved in histone phosphorylation and in histone demethylation were not affected. Alcohol- and alcohol withdrawal-induced alterations were reversible since no significant changes in gene expression were observed 21 days after chronic ethanol exposure (ABS). However, alcohol-induced changes in expression of genes involved in modifying chromatin structure have the potential to modulate the deposition of long-lasting chromatin marks, therefore affecting gene expression long-term.

A major finding emerging from this study is that several genes involved in histone acetylation and deacetylation are altered by alcohol exposure and/or withdrawal, with all of the changes very clearly pointing to reduced acetylation. We found that four histone acetyltransferases (Hat1, Atf2, Kat6a, and Kat6b) are downregulated, while Hdac3 and three key components of the NuRD complex (Mbd3, Chd3, and Mta2), which are involved in histone deacetylation, are upregulated. Together these changes strongly support the hypothesis that chronic ethanol and ethanol withdrawal induce a shift in the histone acetylation/deacetylation equilibrium toward deacetylation.

These results are in agreement with prior studies indicating that chronic alcohol and/or alcohol withdrawal induces chromatin hypo-acetylation in both the adult and developing brain (Guo et al., 2011; Pandey et al., 2008; Sakharkar et al., 2014). Furthermore, an increase in MBD3 mRNA was reported in postmortem brains of alcoholics (Ponomarev et al., 2012).

The short half-life of histone acetylation (between 2–140 min) has been demonstrated in several mammalian cell types, including rat hepatoma cells, human fibroblasts, and human HeLa cells (Barth and Imhof, 2010; Waterborg, 2002; Zheng, Thomas, and Kelleher, 2013). It should be noted, however, that none of these studies were conducted in vivo or in post-mitotic neural cells. Histone acetylation is tightly correlated with the deposition of more stable open chromatin marks, such as H3K4 methylation and reduced DNA methylation (Nightingale et al., 2007). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that ethanol-induced alteration in the balance of acetylation/deacetylation genes in the direction of deacetylation may create a transient chromatin structure that is less favorable to the deposition of stable open chromatin marks and more favorable to the deposition of restrictive chromatin marks.

Histone ubiquitination was also found to be affected at EXP and WD. Protein ubiquitination requires the sequential activities of three classes of enzymes: ubiquitin activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) (Cao and Yan, 2012; Meas and Mao, 2015). UBE2a, an E2 enzyme, and RNF20, an E3 ligase, are involved in the monoubiqutination of lysine 120 of histone H2B (H2BK120ub), an epigenetic mark associated with H3K4 and H3K79 di- and trimethylation and with transcription activation (Cao and Yan, 2012; Meas and Mao, 2015). The decrease in expression of Rnf20 and Ube2a observed at WD and, for Ube2a, at EXP is therefore consistent with silencing of gene expression.

Ethanol and/or ethanol withdrawal affects the expression of 10 histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs). Histone lysine methylation sites associated with activation of transcription are H3K4, H3K36, and H3K79; histone lysine methylation sites associated with transcriptional repression are H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20 (Black et al., 2012; Peter and Akbarian, 2011). The vast majority of the observed alcohol-induced changes in KMTs’ expression are consistent with increased transcription, including downregulation of Setdb1, which trimethylates H3K9; of Ezh2, the catalytic subunit of the repressive complex PRC2, which catalyzes the trimethylation of H3K27; and of Suz12, another member of the PRC2 complex; and upregulation of Setd7, which specifically mono-methylates H3K4; of Setd3 which methylates H3K4 and H3K36; of Ash1l, which methylates H3K36; and of Dot1l, which methylates H3K79. Only two of the changes are consistent with decreased transcription: the downregulation of Smyd3, which di- and trimethylates H3K4; and the downregulation of Setd2, which specifically trimethylates H3K36. Our results are consistent with a previous study carried out in postmortem brains from alcoholics showing an increase in H3K4 methylation in the PFC (Ponomarev et al., 2012).

We also found a reduction in Dnmt1 expression during withdrawal, which is expected to be associated with decreased DNA methylation and increased gene expression. A reduction in DNMT1 was also found in the PFC of alcoholic subjects (Ponomarev et al., 2012), and following acute ethanol administration in the mouse striatum (Botia, Legastelois, Alaux-Cantin, and Naassila, 2012). By contrast, in mice undergoing cycles of excessive alcohol intake and withdrawal, DNMT1 protein expression is increased in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) while alcohol is still present (Warnault et al., 2013). Similarly, two doses of ethanol administered 1 day apart increased Dnmt1 mRNA expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) of adolescent rats while the animals were still intoxicated (Sakharkar et al., 2014).

The Mbd1 gene, encoding for a protein associated with transcriptional repression and heterochromatin formation and maintenance, was upregulated at the same time point. MBD1 binds primarily to methylated CpG sites on the DNA; it also binds SETB1, a H3K9 methylase downregulated during EXP and WD (see previous section). MBD1 is therefore a key player in connecting DNA methylation and H3K9 histone methylation and in directing histone methylation to DNA methylation sites, resulting in silenced gene expression (Du, Luu, Stirzaker, and Clark, 2015; Mazzio and Soliman, 2012). The observed decrease in Dnmt1 and increase in Mbd1, encoding for two proteins strongly associated with gene repression, suggests that compensatory mechanisms may be playing a role in these effects of ethanol.

An exciting result emerging from these studies is that chronic ethanol and/or ethanol withdrawal impact the expression of genes encoding for protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs). PRMTs catalyze the transfer of one methyl group leading to the formation of monomethylarginine (MMA) or two methyl groups, generating asymmetric dimethylarginines (ADMA) or symmetric dimethylarginines (SDMA) (Bedford and Richard, 2005; Di Lorenzo and Bedford, 2011; Morales et al., 2016; Yang and Bedford, 2013). Alcohol-induced downregulation of Prmt1, generating H4R3me2a associated with transcription activation (Yang and Bedford, 2013), and upregulation of Prmt6, generating H3R2me2a associated with transcriptional repression as it prevents the deposition of the transcription-activating H3K4me3 mark (Guccione et al., 2007), are consistent with transcription repression. On the other hand, the downregulation of Prmt5, which functions as a transcriptional repressor by depositing the repressive SDMA marks H3R8me2s and H4R3me2s (Yang and Bedford, 2013), is consistent with transcription activation.

To our knowledge, PRMTs have not been investigated with regard to alcohol addiction. PRMT1 was found to be downregulated in the nucleus accumbens of mice repeatedly exposed to cocaine and was implicated in the behavioral response to cocaine (Li et al., 2015). PRMT6 was found to be downregulated in the nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons expressing dopamine D2 receptors after repeated cocaine exposures; this effect was implicated in the protection against cocaine-induced addictive-like behavioral abnormalities (Damez-Werno et al., 2016). Together these studies support a role for PRTMs in drug addiction, including, perhaps, alcoholism.

We compared our results against a recently published genome-wide study. Microarray analysis carried out in male C57Bl/6J mice after chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) followed by 0 h, 8 h, 72 h, and 7 days withdrawal reported changes in the expression of several of the genes that we identified in this study to be altered by alcohol (Smith et al., 2016). Twenty-five genes that we found to be regulated by alcohol showed concordant regulation at the same time point and in the same brain region in the study by Smith et al. (2016), four genes showed opposite regulation, and the remaining 15 genes we identified to be regulated were not affected. Another recent microarray study carried out in the prefrontal cortex of BXD recombinant inbred mouse strains 72 h following acute and CIE ethanol exposure identified ethanol-induced changes in eight genes involved in chromatin remodeling also altered by alcohol in this study (Rnf20, Bptf, Ash1l, Setd3, Zmynd8, Atf2, Brd2) (van der Vaart et al., 2016). Microarray analysis of human postmortem brain tissue identified 13 genes involved in chromatin remodeling whose expression was also altered in our study; nine of these genes showed the same direction of regulation (Ponomarev et al., 2012). Similarly, RNA sequencing studies of human alcoholic postmortem brain tissue identified changes in seven of the genes that are regulated by ethanol in our study; five of these genes displayed the same direction of regulation (Farris, Harris, and Ponomarev, 2015). The large overlap between our findings and these previous studies, which were carried out in different species or mouse strains and used different paradigms of alcohol exposure, validates and strengthens our findings. Our results together with these observations indicate the particularly robust effects of ethanol on chromatin remodeling gene expression.

Baseline differences were identified between WSR and WSP mice in the expression of genes involved in modifying chromatin structure (Table 3) that may result in different patterns of chromatin and DNA modifications. Interestingly, chromobox protein homolog 3 (Cbx3), that encodes for the protein heterochromatin protein 1γ (HP1γ), was expressed in WSP mice at levels more than 3-fold higher than in WSR mice. CBX3 (HP1γ) localizes to euchromatin or to both euchromatin and heterochromatin, and it may bind H3K9, leading to the condensation of chromatin, but it may also be associated with induction of gene transcription (Canzio, Larson, and Narlikar, 2014; Kwon and Workman, 2011; Mishima et al., 2015). Given the prominent role of this gene in modulating transcription, it may be a good candidate to explore in order to understand the phenotypic differences in alcohol response of these two mouse lines. While we did not identify any line × treatment differences in this study, the combinatorial effects of alcohol-induced changes in gene expression and of differences in base-line expression between WSP and WSR will likely result in different patterns of histone tail and DNA modifications in the two lines following alcohol exposure, ultimately resulting in different levels of expression in the two mouse lines as a result of ethanol exposure.

While this study identifies several genes involved in chromatin remodeling whose expression is altered by chronic ethanol and withdrawal, suggesting that several epigenetic mechanisms are affected by ethanol, there are limitations associated with this study that require further investigation. Indeed, this study: i) was carried out only in male animals, not addressing possible sex-specific effects; ii) does not explore short- and long-term consequences of gene expression changes on chromatin structure; iii) does not provide information on the possible interaction between alcohol and pyrazole, the drug used to inhibit alcohol metabolism; and iv) does not provide information on how long it takes for alcohol-induced changes to return to baseline.

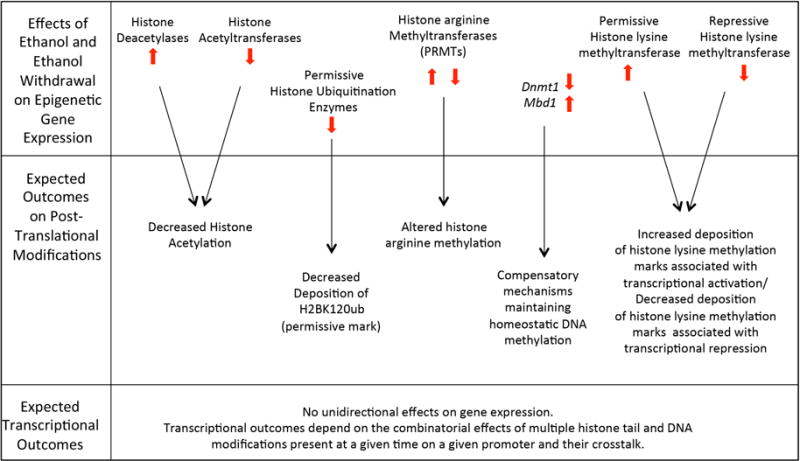

In conclusion, chronic vapor exposure to highly intoxicating levels of ethanol alters the expression of several chromatin remodeling genes. These effects were independent of selected lines, which, however, displayed baseline differences in epigenetic gene expression. In addition, no changes in gene expression were found after 21 days of abstinence. Ethanol-induced changes are consistent with decreased histone acetylation and with decreased deposition of the permissive ubiquitination mark H2BK120ub, associated with reduced transcription. On the other hand, ethanol-induced changes in the expression of genes involved in histone lysine methylation are consistent with increased transcription. The net result of these chromatin modifications on the expression of target genes is likely dependent on the combination of histone tail modifications present at a given time on a given promoter (Fig. 3). It is now well established that individual epigenetic modifications are not a good predictor of expression. Numerous post-translational modifications coexist on the histone tail and together modulate the access of transcription factors to the gene promoter region and are therefore able to modulate the transcriptional outcome of any given gene (Badeaux and Shi, 2013). The numerous post-translational modifications of histone and DNA and their crosstalk have a combinatorial effect on the expression of individual genes (Weake and Workman, 2008). Whether or not a strict “histone code” of post-translational modifications exists, the combination of several histone PTMs regulates chromatin structure and function in modulating gene expression (Gardner, Allis, and Strahl, 2011). Since alcohol does not modulate gene expression unidirectionally (Barbier et al., 2016; Bergeson et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Ponomarev et al., 2012; Wilhelm, Hashimoto, Roberts, Sonmez, and Wiren, 2014), it is not surprising that alcohol does not unidirectionally alter chromatin structure toward a closed or open state, as suggested by the results of this study.

Fig. 3.

Summary of ethanol-induced changes in expression of genes involved in modifying chromatin structure and expected post-translational modification and transcriptional outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Exposure (EXP). Two-way ANOVA analysis of the following groups: Control-t0/WSP; EXP-t0/WSP; Control-t0/WSR; EXP-t0/WSR.

Supplemental Table 2. Withdrawal (WD). Two-way ANOVA analysis of the following groups: Control-8h/WSP; WD-8h/WSP; Control-8h/WSR; WD-8h/WSR;

Supplemental Table 3. Abstinence (ABS). Two-way ANOVA analysis of the following groups: Control-21d/WSP; ABS-21d/WSP; Control-21d/WSR; ABS-21d/WSR.

Highlights.

Ethanol changes gene expression consistently with decreased histone acetylation.

Ethanol changes are consistent with decreased permissive ubiquitination marks.

Ethanol affects gene expression of protein arginine methyl-transferases (PRMTs).

Ethanol changes gene expression of lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) toward permissive lysine methylation marks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs: Merit Review Awards BX001819 (M.G.) and Career Development Award (CDA-2) IK2BX001650 (D.P.G.); National Institutes of Health: R01AA021468, R21AA021876, and R01AA022948 (M.G.), and NARSAD Young Investigator Award donation from The Family of Joseph M. Evans (D.P.G.). We also acknowledge support from VA Merit Review grant 101BX000313, and NIH grants U01 AA013519, P60 AA10760, and R24 AA020245 for the production and maintenance of WSP and WSR mouse colonies and for the use of ethanol vapor chambers. We thank Dr. Pamela Metten for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Badeaux AI, Shi Y. Emerging roles for chromatin as a signal integration and storage platform. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:211–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier E, Johnstone AL, Khomtchouk BB, Tapocik JD, Pitcairn C, Rehman F, et al. Dependence-induced increase of alcohol self-administration and compulsive drinking mediated by the histone methyltransferase PRDM2. Mol Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier E, Tapocik JD, Juergens N, Pitcairn C, Borich A, Schank JR, et al. DNA methylation in the medial prefrontal cortex regulates alcohol-induced behavior and plasticity. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6153–6164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4571-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth TK, Imhof A. Fast signals and slow marks: the dynamics of histone modifications. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadles-Bohling A, Wiren K. Anticonvulsive effects of kappa opioid receptor modulation in an animal model of ethanol withdrawal. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:483–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford MT, Richard S. Arginine methylation an emerging regulator of protein function. Mol Cell. 2005;18:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeson SE, Berman AE, Dodd PR, Edenberg HJ, Hitzemann RJ, Lewohl JM, et al. Expression Profiling in Alcoholism Research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1066–1073. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000171043.29384.3E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol Cell. 2012;48:491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botia B, Legastelois R, Alaux-Cantin S, Naassila M. Expression of ethanol-induced behavioral sensitization is associated with alteration of chromatin remodeling in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canzio D, Larson A, Narlikar GJ. Mechanisms of functional promiscuity by HP1 proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Yan Q. Histone ubiquitination and deubiquitination in transcription, DNA damage response, and cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:26. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera-Juanes R, Wilhelm LJ, Park B, Grant KA, Ferguson B. Genome-wide analysis of the nucleus accumbens identifies DNA methylation signals differentiating low/binge from heavy alcohol drinking. Alcohol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P, Tanner KG, Cheung WL, Sassone-Corsi P, Denu JM, Allis CD. Synergistic coupling of histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation in response to epidermal growth factor stimulation. Mol Cell. 2000;5:905–915. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AL, Mahadevan LC. MAP kinase-mediated phosphoacetylation of histone H3 and inducible gene regulation. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosio C, Heitz E, Allis CD, Borrelli E, Sassone-Corsi P. Chromatin remodeling and neuronal response: multiple signaling pathways induce specific histone H3 modifications and early gene expression in hippocampal neurons. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4905–4914. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damez-Werno DM, Sun H, Scobie KN, Shao N, Rabkin J, Dias C, et al. Histone arginine methylation in cocaine action in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:9623–9628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605045113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DesJarlais R, Tummino PJ. Role of Histone-Modifying Enzymes and Their Complexes in Regulation of Chromatin Biology. Biochemistry. 2016;55:1584–1599. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo A, Bedford MT. Histone arginine methylation. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2024–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q, Luu PL, Stirzaker C, Clark SJ. Methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins: readers of the epigenome. Epigenomics. 2015;7:1051–1073. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SP, Harris RA, Ponomarev I. Epigenetic modulation of brain gene networks for cocaine and alcohol abuse. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:176. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi M, Wade PA. MBD family proteins: reading the epigenetic code. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3033–3037. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegersh A, Ferguson C, Maxwell S, Mazariegos D, Farrell D, Homanics GE. Repeated vapor ethanol exposure induces transient histone modifications in the brain that are modified by genotype and brain region. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:39. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner KE, Allis CD, Strahl BD. Operating on chromatin, a colorful language where context matters. J Mol Biol. 2011;409:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin DP, Kusumo H, Zhang H, Guidotti A, Pandey SC. Role of Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-Inducible, Beta in Alcohol-Drinking Behaviors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:263–272. doi: 10.1111/acer.12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guccione E, Bassi C, Casadio F, Martinato F, Cesaroni M, Schuchlautz H, et al. Methylation of histone H3R2 by PRMT6 and H3K4 by an MLL complex are mutually exclusive. Nature. 2007;449:933–937. doi: 10.1038/nature06166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Crossey EL, Zhang L, Zucca S, George OL, Valenzuela CF, et al. Alcohol exposure decreases CREB binding protein expression and histone acetylation in the developing cerebellum. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto JG, Forquer MR, Tanchuck MA, Finn DA, Wiren KM. Importance of genetic background for risk of relapse shown in altered prefrontal cortex gene expression during abstinence following chronic alcohol intoxication. Neuroscience. 2011;173:57–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto JG, Wiren KM. Neurotoxic consequences of chronic alcohol withdrawal: expression profiling reveals importance of gender over withdrawal severity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1084–1096. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg RD. Structure of chromatin. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1977;46:931–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.004435. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.004435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosobud A, Crabbe J. Ethanol withdrawal in mice bred to be genetically prone or resistant to ethanol withdrawal seizures. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238:170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SH, Workman JL. The changing faces of HP1: From heterochromatin formation and gene silencing to euchromatic gene expression: HP1 acts as a positive regulator of transcription. Bioessays. 2011;33:280–289. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhu R, Wang W, Fu D, Hou J, Ji S, et al. Arginine Methyltransferase 1 in the Nucleus Accumbens Regulates Behavioral Effects of Cocaine. J Neurosci. 2015;35:12890–12902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0246-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lewohl JM, Harris RA, Iyer VR, Dodd PR, Randall PK, et al. Patterns of gene expression in the frontal cortex discriminate alcoholic from nonalcoholic individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1574–1582. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathies LD, Blackwell GG, Austin MK, Edwards AC, Riley BP, Davies AG, et al. SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling regulates alcohol response behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans and is associated with alcohol dependence in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3032–3037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413451112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzio EA, Soliman KF. Basic concepts of epigenetics: impact of environmental signals on gene expression. Epigenetics. 2012;7:119–130. doi: 10.4161/epi.7.2.18764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meas R, Mao P. Histone ubiquitylation and its roles in transcription and DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst) 2015;36:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima Y, Jayasinghe CD, Lu K, Otani J, Shirakawa M, Kawakami T, et al. Nucleosome compaction facilitates HP1gamma binding to methylated H3K9. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:10200–10212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales Y, Caceres T, May K, Hevel JM. Biochemistry and regulation of the protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;590:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale KP, Gendreizig S, White DA, Bradbury C, Hollfelder F, Turner BM. Cross-talk between histone modifications in response to histone deacetylase inhibitors: MLL4 links histone H3 acetylation and histone H3K4 methylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4408–4416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Ugale R, Zhang H, Tang L, Prakash A. Brain chromatin remodeling: a novel mechanism of alcoholism. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3729–3737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5731-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins JR, Dawes JM, McMahon SB, Bennett DL, Orengo C, Kohl M. ReadqPCR and NormqPCR: R packages for the reading, quality checking and normalisation of RT-qPCR quantification cycle (Cq) data. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:296. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter CJ, Akbarian S. Balancing histone methylation activities in psychiatric disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarev I, Wang S, Zhang L, Harris RA, Mayfield RD. Gene coexpression networks in human brain identify epigenetic modifications in alcohol dependence. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1884–1897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3136-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repunte-Canonigo V, Chen J, Lefebvre C, Kawamura T, Kreifeldt M, Basson O, et al. MeCP2 regulates ethanol sensitivity and intake. Addict Biol. 2014;19:791–799. doi: 10.1111/adb.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roloff TC, Ropers HH, Nuber UA. Comparative study of methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakharkar AJ, Tang L, Zhang H, Chen Y, Grayson DR, Pandey SC. Effects of acute ethanol exposure on anxiety measures and epigenetic modifiers in the extended amygdala of adolescent rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:2057–2067. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714001047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer G, Crabbe J, Wiren K. Identification of neuroendocrine-specific protein as an ethanol-regulated gene with mRNA differential display. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:979–982. doi: 10.1007/s003359900910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuebel K, Gitik M, Domschke K, Goldman D. Making Sense of Epigenetics. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Lopez MF, Archer KJ, Wolen AR, Becker HC, Miles MF. Time-Course Analysis of Brain Regional Expression Network Responses to Chronic Intermittent Ethanol and Withdrawal: Implications for Mechanisms Underlying Excessive Ethanol Consumption. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner DE, Berger SL. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:435–459. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.435-459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey AJ, Dabney A, Robinson DJ, with contributions from B qvalue: Q-value estimation for false discovery rate control. 2015 Retrieved from http://github.com/jdstorey/qvalue.

- van der Vaart AD, Wolstenholme JT, Smith ML, Harris GM, Lopez MF, Wolen AR, et al. The allostatic impact of chronic ethanol on gene expression: A genetic analysis of chronic intermittent ethanol treatment in the BXD cohort. Alcohol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnault V, Darcq E, Levine A, Barak S, Ron D. Chromatin remodeling–a novel strategy to control excessive alcohol drinking. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e231. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterborg JH. Dynamics of histone acetylation in vivo. A function for acetylation turnover? Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;80:363–378. doi: 10.1139/o02-080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weake VM, Workman JL. Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity. Mol Cell. 2008;29:653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler JM, Reed C, Burkhart-Kasch S, Li N, Cunningham CL, Janowsky A, et al. Genetically correlated effects of selective breeding for high and low methamphetamine consumption. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:758–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm CJ, Hashimoto JG, Roberts ML, Bloom SH, Beard DK, Wiren KM. Females uniquely vulnerable to alcohol-induced neurotoxicity show altered glucocorticoid signaling. Brain Res. 2015;1601:102–116. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm CJ, Hashimoto JG, Roberts ML, Sonmez MK, Wiren KM. Understanding the addiction cycle: a complex biology with distinct contributions of genotype vs. sex at each stage. Neuroscience. 2014;279:168–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiren KM, Semirale AA, Hashimoto JG, Zhang XW. Signaling pathways implicated in androgen regulation of endocortical bone. Bone. 2010;46:710–723. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Bedford MT. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:37–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahr NM, Mayer D, Rohlfing T, Hasak MP, Hsu O, Vinco S, et al. Brain injury and recovery following binge ethanol: evidence from in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:846–854. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Thomas PM, Kelleher NL. Measurement of acetylation turnover at distinct lysines in human histones identifies long-lived acetylation sites. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2203. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Exposure (EXP). Two-way ANOVA analysis of the following groups: Control-t0/WSP; EXP-t0/WSP; Control-t0/WSR; EXP-t0/WSR.

Supplemental Table 2. Withdrawal (WD). Two-way ANOVA analysis of the following groups: Control-8h/WSP; WD-8h/WSP; Control-8h/WSR; WD-8h/WSR;

Supplemental Table 3. Abstinence (ABS). Two-way ANOVA analysis of the following groups: Control-21d/WSP; ABS-21d/WSP; Control-21d/WSR; ABS-21d/WSR.