Abstract

Objective:

Unsuccessful linkage to care and treatment increases adolescent HIV-related morbidity and mortality. This study evaluated the effect of a novel adolescent and youth Red Carpet Program (RCP) on the timing and outcomes of linkage to care.

Design:

A prepost implementation evaluation of the pilot RCP program.

Settings:

Healthcare facilities (HCFs) and schools in Homa Bay County, Kenya.

Study participants:

HIV-infected adolescents (15–19 years) and youth (20–21 years).

Interventions:

RCP provided fast-track peer-navigated services, peer counseling, and psychosocial support at HCFs and schools in six Homa Bay subcounties in 2016. RCP training and sensitization was implemented in 50 HCFs and 25 boarding schools.

Main outcome measures:

New adolescent and youth HIV diagnosis, linkage to and retention in care and treatment.

Results:

Within 6 months of program rollout, 559 adolescents and youths (481 women; 78 men) were newly diagnosed with HIV (15–19 years n = 277; 20–21 years, n = 282). The majority (n = 544; 97.3%) were linked to care, compared to 56.5% at preimplementation (P < 0.001). All (100.0%; n = 559) adolescents and youths received peer counseling and psychosocial support, and the majority (n = 430; 79.0%) were initiated on treatment. Compared to preimplementation, the proportion of adolescents and youths who were retained on treatment increased from 66.0 to 90.0% at 3 months (P < 0.001), and from 54.4 to 98.6% at 6 months (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Implementation of RCP was associated with significant improvement in linkage to and early retention in care among adolescent and youth. The ongoing study will fully assess the efficacy of this linkage-to-care approach.

Keywords: adolescents, HIV, linkage to care, retention in care, schools, youth

Introduction

The 2014 WHO guidelines on adolescents and HIV recommend HIV testing and counseling (HTC) with linkage to prevention, treatment, and care for all adolescents in the settings of generalized epidemics [1]. As the global community intensifies case finding among adolescents and youth [2], it becomes evident that there is an unmet need for efficient linkage to care and treatment among these populations [1,3–5]. Most HTC and linkage to care and treatment services for adolescents and youth tend to replicate strategies designed for adults and frequently do not take into account the specific barriers faced by adolescents and youth, such as economic, legal, and social dependence; inadequate provider skills in caring for and communicating with adolescents and youth; and requirements for involvement of a guardian [1,4,6]. There has been a paucity of data regarding targeted interventions to improve linkage to care among adolescents living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Factors that have been shown to negatively affect linkage to and retention in care among adolescents and youth living with HIV include the legal and cultural constraints around the age of consent, lack of adolescent-friendly services within healthcare settings, and individual-level factors [1,6–9]. Loss to follow-up during the period between positive HIV testing and linkage to care, delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), and poor levels of early retention in care significantly contribute to high HIV-related morbidity and mortality globally among adolescents and youth [8,10–14]. Addressing these challenges is particularly important during the initial stage following a new diagnosis of HIV in adolescents and youth, a time when successful initiation into the HIV care cascade may improve long-term outcomes and decrease HIV transmission among these key populations.

The Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF), working across 14 countries, reaches more than 500 000 adolescents and youths each year with HTC, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, and HIV care and treatment services. EGPAF has prioritized scaling up adolescent and youth-focused programs in high-burden areas, such as Kenya, where in 2015, 51% of all new HIV infections occurred among youth ages 15–24 years [15]. One of these high-burden areas is Homa Bay County, which in 2015 had an estimated population of 279 862 adolescents and youths and an overall HIV prevalence of 26% [16], with 2.9% prevalence among adolescents and youth ages 15–24 years (unpublished data, Pamoja project).

Practices based on a ‘linkage-to-care officer’ who facilitates intra and interfacility referrals have had limited success in linking the adolescents and youth living with HIV to care and treatment in the Homa Bay area, where loss to follow-up after a positive HIV test was identified as a barrier to linkage to care and treatment among adolescents and youth (EGPAF data, unpublished). To address this gap, in 2016, with the support of funding by the grant from the Positive Action for Adolescents Programme by ViiV Healthcare UK Ltd, London, UK, EGPAF implemented the Red Carpet Program (RCP), a concept adapted from a successful linkage-to-care program from an area of high HIV prevalence in Washington, DC, USA (https://doh.dc.gov/service/red-carpet-entry-program) [17,18]. The goal of Kenya RCP was to develop, implement, and evaluate a comprehensive, fast-track, peer-designed linkage-to-care and early retention program with interlinked facility and community-level components. Populations of focus included female and male adolescents and youth with perinatally and behaviorally (horizontally) acquired HIV within two age subgroups: adolescents 15–19 years of age (attending secondary schools and out of school) and youth 20–21 years of age (attending colleges and out of school). The current study evaluated the effect of the pilot RCP on the timing and outcomes of linkage to care and treatment, as well as early retention on ART, among adolescents and youth newly diagnosed with HIV in Homa Bay County.

Methods

Fast-track peer-navigated services providing linkage to care and treatment were implemented in public healthcare facilities (HCFs) and schools within six subcounties of Homa Bay County, Kenya (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map of the Red Carpet Program subcounties in Homa Bay County.

Study participants were adolescents (15–19 years) and youths (20–21 years) from Homa Bay County who were newly diagnosed with HIV, identified through HCF and community outreach HTC.

Study design was a prepost evaluation of the effect of RCP on the linkage to care and retention on ART. The RCP study protocol was approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital–University of Nairobi Ethical Review Board, Kenya, and Chesapeake Institutional Review Board, USA. The study obtained a waiver of informed consent, as it was no more than minimal risk to participants and the study could not practicably be carried out without a waiver. All adolescents and youth, ages 15–21 years who were newly diagnosed with HIV in six RCP Homa Bay subcounties were eligible for study participation. The participants were stratified into two cohorts based on age: adolescents (15–19 years) and youth (20–21 years).

Data collection: For the preimplementation data, we conducted retrospective medical records review of the adolescents and youth newly diagnosed with HIV during the 6-month period from July 2015 to December 2015, prior to the startup of the RCP in 2016. These data were extracted between August 2016 and October 2016. All of the participants in the study had data available for 3 and 6-month follow-up. When it was not possible to identify records showing enrollment in and/or retention in care, the participants were classified as not being linked to care and/or not being retained in care, as applicable. As part of the preimplementation evaluation, we also conducted an assessment of adolescent-friendly services at 50 HCFs selected for implementing the RCP. For the postimplementation study, we conducted a prospective review of medical records of the adolescents and youth newly diagnosed with HIV who used the RCP, as well as collected RCP program data for the period from July 2016 to December 2016. For this pilot analysis, the prospective linkage-to-care data are available for all participants, whereas 3 and 6-month retention data are limited to those participants who completed 3 and 6 months of follow-up. The demographic data included age and sex. Data quality was assured through regular quality assurance activities, including mentorship on data collection tools. Quality assurance indicators were developed for newly diagnosed adolescents and youth on linkage to care, as well as early retention in care and early retention on ART. Performance review meetings were conducted quarterly at all involved HCFs and at the subcounty and county levels.

Red Carpet Program interventions

Stakeholder involvement included: engaging the Ministry of Health, county and subcounty teams, and other regional partners to review the current data on linkage to care and treatment services with a focus on adolescents and youth, as well as the programmatic data; involving stakeholders in the design of the RCP; engaging the Ministry of Education and school leadership; and convening the stakeholder meeting in partnership with the County Education Office and the School Heads and Managers Association to introduce the adolescent and youth HIV and RCP agendas.

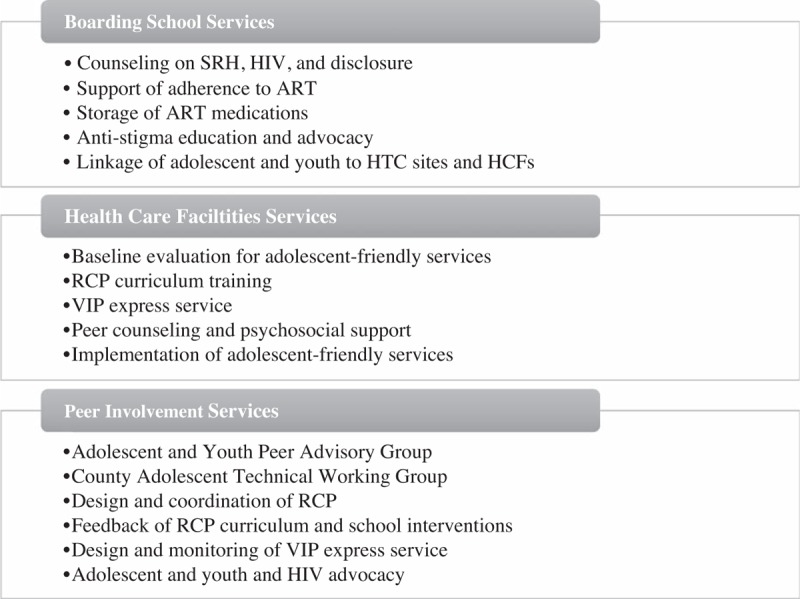

From January 2016 to February 2016, a series of sensitization meetings were held with the county and subcounty health management teams, and key regional partners and stakeholders in health, education, and adolescent and youth support. The county also formed a 12-member Adolescent Technical Working Group, which included two adolescents and youth per subcounty; identified a focal RCP person; and designated subcounty health management team members to lead coordination of RCP activities (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Red Carpet Program packages of services.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; HCF, healthcare facility; HTC, HIV testing and counselling; RCP, Red Carpet program; SRH, sexual and reproductive health.

In May 2016, a project sensitization meeting was held with Ministry of Education County Managers, the County Educational Office, school heads, education officers, and school principals from all secondary schools (n = 350) in Homa Bay. As a result, all schools agreed to implement treatment and adherence support services for adolescents and youth living with HIV in secondary boarding schools and improve linkage to HCFs and adolescent health services in Homa Bay. In total, 25 high-volume boarding secondary schools piloted the school-based support programs for adolescents and youth living with HIV, which included: counseling on HIV and sexual and reproductive health (SRH); creating a supportive environment to ensure ART adherence; creating health clubs and health education to address anti-HIV stigma; facilitating storage of HIV medications at school when necessary; supporting and providing counselling on disclosure of HIV status; and supporting linkage to HCFs (Fig. 2). The RCP conducted a 2-day capacity-building workshop for 50 adolescent and youth advocates (including, but not limited to, adolescents and youth living with HIV) and guidance and counselling teachers, matrons, and nurses in 25 boarding schools. The training addressed key issues in adolescent and youth HIV support, including the Kenya Education Sector Policy on HIV/AIDS.

Peer involvement included identifying adolescents and youth living with HIV as participants for the Adolescent and Youth Peer Advisory Group (AYPAG) to inform the development and implementation of RCP services (Fig. 2). In February 2016, 36 HIV-infected adolescent and youth advocates (15–21 years) from participating Homa Bay subcounties were invited to form the AYPAG and received capacity-building training on communication and presentation skills. The AYPAG designed the very important person (VIP) express card and VIP express services, and provided feedback on the RCP training curriculum. The AYPAG also selected six champions from the group to participate in the Adolescent Technical Working Group.

During the first half of 2016, the RCP identified peer educators living with HIV and RCP coordinators (nurses and/or clinical officers) to form RCP teams at 50 HCFs. The RCP team designed and wrote a 3-day training curriculum to build the capacity of healthcare workers and peer educators in care for adolescents and youth living with HIV, with a focus on linkage to care and early retention for newly identified youth. The curriculum included eight modules addressing key topics on HIV, SRH, and mental health needs and services relevant for adolescents and youth living with HIV. Using this curriculum, RCP conducted phased capacity building with the 50 HCFs from August 2016 to October 2016 and trained 56 RCP coordinators and 56 peer educators.

VIP express service interventions included: a VIP express card designed by AYPAG was issued to the adolescents and youth who tested positive for HIV; fast-track access to HCFs, peer counseling, and psychosocial support services (PSS) was facilitated; HCFs were made adolescent and youth friendly (adolescent and youth-trained staff, adolescent and youth-targeted posters, and adolescent and youth-targeted clinic areas) to welcome newly identified adolescents and youth and guide them through initial registration and follow-up; flexible hours were set up at HCFs and for peer counseling and PSS (Fig. 2).

A baseline assessment that aimed to identify challenges in provision of adolescent and youth-friendly HIV services was conducted in 50 RCP-designated HCFs by the RCP team. Among 50 HCFs, only two reported having a daily integrated adolescent clinic. Key findings from the HCF assessments were as follows: 52% of HCFs had designated peer educators to support adolescents and youth, adolescents and youth waited more than 30 min during the first visit at 60% of HCFs, adolescents and youth waited more than 30 min during repeat visits at 50% of HCFs, 26% of HCFs had a designated adolescent service provider, and 88% of HCFs had a waiting time greater than 1 month for the first appointment.

There were no structured linkages between schools and HCFs and no structured curricula on adolescent and youth HIV support. As a result, the RCP identified strategies for implementing adolescent and youth-friendly services (VIP express service, flexible and extended hours, peer educator support, and adolescent and youth trained personnel) at the HCFs. Feedback on the findings was provided to RCP coordinators and HCF staff implementing the project during RCP training, and site-level work plans and monitoring and evaluation tools were developed. Standardized adjustments were made across RCP facilities, including increased flexibility of clinic hours with weekend clinics, universal peer counseling and PSS, establishment of adolescent and youth-friendly waiting and counseling areas, and adolescent and youth peer counseling training. PSS was provided at all 50 sites by the peer educators, clinicians/nurses, and adherence counselors. Peer counseling was provided by adolescents and youth at all 50 sites; group counseling and individual counseling were available based on specific needs.

For example, Nyagoro Health Center, where linkage to care for adolescents and youth took more than 2 months at preimplementation, adopted a ‘one-stop shop’ approach for the provision of adolescent and youth HIV services through a reverse referral strategy where the clinician and support team are referred to the client. Nyagoro HCF identified a separate room where peer educators and healthcare workers provide a comprehensive package of services within the same adolescent and youth-friendly space, eliminating the need for adolescents and youth to go to other departments/service points following diagnosis of HIV. This and other similar innovations were shared at the two review meetings on best practices held in Rangwe subcounty and Nyagoro Health Center in 2016.

From June 2016 to December 2016, 50 HCFs implemented the VIP express services, where the VIP express card, through an individual tracking number, triggers the facilitated access to services including initial registration, baseline peer counseling, and the PSS assessment. RCP partnered with the Kenyan nongovernmental organization LVCT Health to provide hotline access for RCP clients. The hotline, called one2one, is toll-free and operates daily, and provides access to RCP, peer counseling, and PSS. The hotline number is included on the VIP express card.

Main outcome measures included: linkage to care, which was defined as a completed first appointment with an HIV care provider following a positive HIV test; and retention on ART, which was defined as being in care with a record of having been dispensed ART at the time of the evaluation. The study collected the following linkage to care and treatment and early retention data: number of adolescents and youth identified as HIV positive; proportion of newly identified adolescents and youth who were linked to care (completed first appointment) within 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, and more than 3 months after testing; proportion of newly diagnosed adolescents and youth who were initiated on ART; and proportion of newly diagnosed adolescents and youth who were initiated and retained on ART at 3 and 6 months after being diagnosed.

Data analysis consisted of using descriptive statistics to characterize the study cohorts. For the RCP comparative analysis, we used preimplementation data from July 2015 to December 2015 as a baseline and compared it with the postimplementation data from July 2016 to December 2016. The demographic, HIV, and linkage to care, initiation, and retention on ART data were compared using chi-square tests, with significance levels P ≤ 0.05.

Results

The preimplementation retrospective data were collected August 2016 to October 2016 on 393 newly identified adolescents and youths for the period July 2015 through December 2015 (Table 1). These baseline data were compared with the 559 adolescents and youth newly diagnosed with HIV during pilot RCP implementation during July 2016 to December 2016. Within pre and postimplementation adolescent and youth cohorts, the majority were women in both adolescent and youth age groups. The proportion of adolescent and youth clients who were linked to care increased from 56.5 to 97.3% (P < 0.001) (Table 1). All adolescents and youth linked to care through RCP received peer counseling and PSS (no data available for the preimplementation cohort). For the timing of linkage to care and treatment, there was no difference in the timing of linkage to care and treatment, as most adolescents and youth who were linked to care were linked within 1 month after HIV diagnosis and were initiated on treatment in both pre and postimplementation cohorts (Tables 1 and 2). Data on the linkage to and retention in care within 3 months were available for the RCP clients enrolled into the project within first 3 months (N = 432). Data on the retention in care at 6 months were available for the 146 RCP clients linked to care within first month of the RCP. Compared with the preimplementation cohort, retention on ART for the postimplementation cohort increased from 66.0 to 90.0% at 3 months (P < 0.001), and from 54.4 to 98.6% at 6 months (P < 0.001; Table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of newly identified HIV-infected adolescents and youth (pre and postintervention).

| Preintervention July 2015–December 2015 N = 393 | Postintervention July 2016–December 2016 N = 559 | |

| Age | ||

| 15–19 | 203 (51.7)a | 277 (49.6) |

| 20–21 | 181 (46.1) | 282 (50.4) |

| Missing/unknown | 9 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 343 (87.3) | 481 (86.0) |

| Male | 46 (11.7) | 78 (14.0) |

| Missing/unknown | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Linkage to care | ||

| Linked to care | 222 (56.5)b | 544 (97.3)b |

| Not linked to care | 171 (43.5)b | 15 (2.7)b |

| ARTc | N = 222 | N = 544 |

| Initiated on ART | 160 (72.1)d | 430 (79.0) |

| Pre-ART | 62 (27.9)d | 114 (21.0)e |

ART, antiretroviral therapy.

aNumber (percentage).

bP < 0.0001.

cData available for those linked to care.

dIn care, not initiated on ART.

eSome recently identified patients have not yet had the chance to start ART.

Table 2.

Timing of the linkage to care (pre and postintervention).

| Time to linkage to care | Preintervention N = 215a | Postintervention N = 544a | ||||

| 15–19 years | 20–21 years | Total | 15–19 years | 20–21years | Total | |

| 1 months | 108 (90.0)b | 86 (90.5) | 194 (90.2) | 228 (85.1) | 238 (86.2) | 466 (85.7) |

| 2 months | 4 (3.3) | 5 (5.3) | 9 (4.2) | 20 (7.5) | 22 (8.0) | 42 (7.7) |

| 3 months | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.1) | 4 (1.9) | 14 (5.2) | 10 (3.6) | 24 (4.4) |

| >3 months | 6 (5.0) | 2 (2.1) | 8 (3.7) | 6 (2.2) | 6 (2.2) | 12 (2.2) |

aData available from 215 patients out of 222 linked to care in preintervention period and for 544 patients linked to care in postintervention period.

bNumber (percentage).

Table 3.

Retained on antiretroviral therapy (pre and postintervention).

| Retained in care | Preintervention | Postintervention |

| At 3 months | 142/215 (66.0)a,b | 389/432c (90.0b |

| At 6 months | 117/215 (54.4)b | 144/146d (98.6)b |

aNumber (percentage).

bP < 0.0001.

cData for 3 months available for 432 patients enrolled within the first 3 months of the Red Carpet Program launch.

dData at 6 months available for 146 patients enrolled within the first month of the Red Carpet Program launch.

Discussion

We reported data from the pilot innovative peer-designed, fast-track adolescent and youth program on linkage to care and treatment – the RCP – that was rolled out in an area with high HIV prevalence in Kenya. Implementation of the RCP was associated with improved linkage to care and better early retention on ART among newly identified adolescents and youth living with HIV. The timing of the linkage to care was not significantly affected by RCP implementation. Our prepost design did not have contemporaneous comparison groups, so we cannot rule out background secular trends, although the magnitude of the changes prepost may reflect the benefits of our intervention.

Several important factors may have contributed to the success of our program. At the national level, where an estimated 24% of the population are less than 20-years old, Kenya has placed a strong focus on adolescent populations, creating the national policy on Adolescent Reproductive Health and Development in 2003 and updating it in 2015 [19]. HTC has become a key element of Kenya's HIV response, with a dramatic rise in the number of people tested for HIV in recent years [20]. In late 2015, Kenya began to transition to the universal initiation of ART for people of all ages living with HIV. Although this could have increased our rates of ART initiation, it is less likely to have affected rates of adolescents and youth linkage to care and treatment, considering the significant increase in need for services across all ages and the timeline required to transition the new guidelines into practice. The county Ministry of Health and local stakeholders’ support also played a major role in the successful implementation of the RCP. Recent scale-up in the number of regional HTC activities among adolescents and youth has contributed to higher adolescent and youth sensitization among key stakeholders. Most HTC activities, however, have focused on the numbers tested, and there has been a gap in identifying best approaches for linkage to care and treatment among adolescents and youth. The introduction of the RCP provided the much-needed step to facilitate the continuum of HIV services and regional HTC efforts. In both the pre and postimplementation cohorts, the majority of participants were women. Given that adolescent and men are less likely to attend healthcare services, additional community-based approaches are needed to increase the numbers of tested and newly identified male adolescents and youth [21–24].

Adolescent and youth staff training and implementation of adolescent and youth-friendly services have been shown to facilitate engagement in care among adolescent and youth populations [5,11,25–27]. Active engagement of peers in the design and delivery of HIV services has also been promoted globally in recent years [1,26]. Yet, the evidence supporting the beneficial role of peers in the continuum of the HIV services is limited and is sometimes controversial [5,28–30]. In the RCP, the involvement of adolescents and youth in the design and delivery of linkage-to-care services established an ongoing dialogue between the local healthcare workers and their adolescent and youth clients. For example, it was through the AYPAG feedback that the higher levels of perception of stigma among horizontally infected adolescents and youth compared to those who acquired HIV perinatally was identified as a significant barrier to linkage to care and was communicated to the healthcare providers. AYPAG's advocacy role has also laid the foundation for further capacity building among adolescents and youth leaders within Homa Bay County and nationally for stronger collaboration with the educational sector.

Adolescents and youth, particularly those less than 19 years, spend a substantial amount of their daily lives in schools. The role of the educational sector in preventing HIV among adolescents and youth has been highlighted globally; however, the data on the engagement of schools in supporting adolescents and youth living with HIV, particularly those with newly identified HIV, are scarce [31,32]. In our experience, the educational sector was supportive of moving forward the agenda on adolescents and youth and HIV and was open to the training and collaboration with HCFs. Although multiple cultural, religious, and societal barriers frequently limit the dialogue on SRH and HIV issues within schools, the meaningful involvement of the teachers, school counselors, and school nurses/matrons can create a supportive environment for adolescents and youth living with HIV while facilitating HIV prevention and education among noninfected adolescents and youth [33,34].

Among the limitations of the RCP implementation, the timely collection and quality of the patient-level data to effectively inform the project targets and implementation were most challenging. Going forward, we have established weekly adolescents and youth linkage-to-care and treatment data reviews to improve the patient-level data reporting. We did not have a prospective concurrent control group to compare outcome data. The populations captured in the pre and postintervention periods, whereas being similar demographically, may be different with respect to other important confounding factors. Moreover, the preimplementation data included only individuals who had completed 6 months of follow-up, whereas the postimplementation data included all adolescents and youth diagnosed during the period, regardless of whether they had completed 6 months of follow-up. This differential data collection potentially weakens our ability to draw strong conclusions. The current RCP curriculum needs additional modules on postexposure and preexposure prophylaxis, and sex violence and life skills, and needs to be better adapted for nonmedical staff. Finally, while promising, our pilot results must be followed by more detailed patient and virologic outcome data, which are currently being collected.

Our prospective RCP activities include scale-up of the program in Turkana County, involvement of community health workers, facilitated HTC for partners and peers of adolescent and youth clients, further growth of the AYPAG, capacity building for adolescents and youth including PSS groups, and potential expansion of the program. The future activities will also focus on using social media platforms as part of the RCP.

In conclusion, the 2014 Adolescent HIV WHO guidelines cite very low-quality evidence for their HTC recommendations. Our study reports pilot data on the peer-designed fast-track service delivery model aimed at improving the linkage to and engagement in care, including early retention on ART, among adolescents and youth with newly identified HIV. Better integration of healthcare and educational sectors is proposed to optimize retention in care and on treatment among HIV-infected adolescents and youth. Ongoing implementation and outcome data collection will allow us to fully evaluate and further develop this promising approach. When proven sustainable, this approach can be adapted to other HTC models, such as community-based HIV testing and self-testing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the adolescents and youth supporting and participating in the RCP. Specifically, we would like to thank the members of the AYPAG, who dedicated their time and efforts to the design of the program and continue to inspire and support it. We extend our special thanks to the regional healthcare and education leaders of Homa Bay County, who have supported the design and implementation of the RCP.

Funding Source: The Red Carpet Program and this study have been supported by the funding by the grant from the Positive Action for Adolescents Programme by ViiV Healthcare UK Ltd, London, UK under the Positive Action for Adolescents Program. EGPAF's adolescent and youth-focused programs in Kenya are supported by funding from United States Government (USG), the Elton John AIDS Foundation (EJAF), the Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), ELMA Philanthropies, and ViiV Healthcare UK Ltd, London, UK.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, HIV and adolescents: guidance for HIV testing and counselling and care for adolescents living with HIV: recommendations for a public health approach and considerations for policy-makers and managers. 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Govindasamy D, Meghij J, Kebede Negussi E, Clare Baggaley R, Ford N, Kranzer K. Interventions to improve or facilitate linkage to or retention in pre-ART (HIV) care and initiation of ART in low- and middle-income settings: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Govindasamy D, Ferrand RA, Wilmore SM, Ford N, Ahmed S, Afnan-Holmes H, et al. Uptake and yield of HIV testing and counselling among children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18:20182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacPherson P, Munthali C, Ferguson J, Armstrong A, Kranzer K, Ferrand RA, et al. Service delivery interventions to improve adolescents’ linkage, retention and adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV care. Trop Med Int Health 2015; 20:1015–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, DuVal A, Ellen JM, Xu J, Kapogiannis B, et al. Factors affecting linkage to care and engagement in care for newly diagnosed HIV-positive adolescents within fifteen adolescent medicine clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav 2014; 18:1501–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tso LS, Best J, Beanland R, Doherty M, Lackey M, Ma Q, et al. Facilitators and barriers in HIV linkage to care interventions: a qualitative evidence review. AIDS 2016; 30:1639–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobat R, Archary M, Lawler M. An update on the HIV treatment cascade in children and adolescents. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015; 10:411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Retention of adolescents living with HIV in care, treatment, and support programs in Uganda: HIVCore Final Report. Available at: http://www.hivcore.org/Pubs/Uganda_AdolHAART_Rprt.pdf [Accessed February 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philbin MM, Tanner AE, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD. Linking HIV-positive adolescents to care in 15 different clinics across the United States: creating solutions to address structural barriers for linkage to care. AIDS care 2014; 26:12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb MR, Fayorsey R, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Viola V, Mutabazi V, Alwar T, et al. High attrition before and after ART initiation among youth (15-24 years of age) enrolled in HIV care. AIDS 2014; 28:559–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koech E, Teasdale CA, Wang C, Fayorsey R, Alwar T, Mukui IN, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of HIV-infected youth and young adolescents enrolled in HIV care in Kenya. AIDS 2014; 28:2729–2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyer CB, Walker BC, Chutuape KS, Roy J, Fortenberry JD. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Creating systems change to support goals for HIV continuum of care: the role of community coalitions to reduce structural barriers for adolescents and young adults. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv 2016; 15:158–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nkala B, Khunwane M, Dietrich J, Otwombe K, Sekoane I, Sonqishe B, et al. Kganya Motsha Adolescent Centre: a model for adolescent friendly HIV management and reproductive health for adolescents in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS Care 2015; 27:697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenya Ministry of Health. Kenya AIDS Response Progress report 2016. Available at: www.nacc.or.ke [Accessed 17 January 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2015) ’Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.District of Columbia Department of Health. Annual Epidemiology and Surveillance Report. HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD and TB Administration. Surveillance data through December 2011. Executive Summary. 2012. Available at: http://doh.dc.gov [Accessed 11 January 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 18.District of Columbia Department of Health. HIV Care and Ryan White Care Dynamics. HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis 1; STD and TB Administration data through 2014. Available at: http://doh.dc.gov [Accessed 11 January 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenya National Adolescent and Reproductive Health Policy. Availale at: http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2015STEPUP_KenyaNationalAdolSRHPolicy.pdf [Accessed 07 January 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 20.UNAIDS. Prevention Gap Report 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS (2012). World AIDS Day Report – Results. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asaolu IO, Gunn JK, Center KE, Koss MP, Iwelunmor JI, Ehiri JE. Predictors of HIV testing among youth in Sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. PloS One 2016; 11:e0164052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanner AE, Philbin MM, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD, et al. ‘Youth friendly’ clinics: considerations for linking and engaging HIV-infected adolescents into care. AIDS Care 2014; 26:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Advisory Panel on HIV Care Continuum Optimization. IAPAC Guidelines for Optimizing the HIV Care Continuum for Adults and Adolescents. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2015; 14 Suppl 1:S3–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reif LK, Bertrand R, Benedict C, Lamb MR, Rouzier V, Verdier R, et al. Impact of a youth-friendly HIV clinic: 10 years of adolescent outcomes in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19:20859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J. The effect of peers on HIV infection expectations among Malawian adolescents: using an instrumental variables/school fixed effect approach. Soc Sci Med 2016; 152:61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menon A, Glazebrook C, Campain N, Ngoma M. Mental health and disclosure of HIV status in Zambian adolescents with HIV infection: implications for peer-support programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007; 46:349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funck-Brentano I, Dalban C, Veber F, Quartier P, Hefez S, Costagliola D, et al. Evaluation of a peer support group therapy for HIV-infected adolescents. AIDS 2005; 19:1501–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason-Jones AJ, Sinclair D, Mathews C, Kagee A, Hillman A, Lombard C. School-based interventions for preventing HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 11:CD006417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul-Ebhohimhen VA, Poobalan A, van Teijlingen ER. A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2008; 8:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nleya PT, Segale E. How setswana cultural beliefs and practices on sexuality affect teachers’ and adolescents’ sexual decisions, practices, and experiences as well as HIV/aids and STI prevention in select Botswanan secondary schools. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2015; 14:224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abubakar A, Van de Vijver FJ, Fischer R, Hassan AS, Gona JK, Dzombo JT, et al. ‘Everyone has a secret they keep close to their hearts’: challenges faced by adolescents living with HIV infection at the Kenyan coast. BMC Public Health 2016; 16:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]