Considerable progress has been made in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of oral diseases in the United States, and yet, certain segments of the population continue to experience disproportionate and unacceptable burdens of these diseases. Conditions such as dental caries and periodontal diseases remain among the most common health problems that afflict disadvantaged and underserved communities. These differences were highlighted in 2000 in “Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General,” the first US Surgeon General’s report covering oral health.1 The report concluded that “there are profound and consequential disparities in the oral health of our citizens. Indeed, what amounts to a ‘silent epidemic’ of dental and oral diseases is affecting some population groups.”

Distinct oral health disparities and inequities continue to exist among low-income racial/ethnic minority groups, those residing in medically and dentally underserved rural and urban areas, and those with developmental or acquired disabilities, including frail and functionally dependent older adults. An analysis of data from the 2009 to 2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that the prevalence of periodontitis increased with age and was almost 20% greater among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks than among non-Hispanic Whites.2 Data from NHANES 2011 to 2012 revealed that rates of untreated dental caries were twice as high among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black children aged two to eight years compared to non-Hispanic White children in the same age group; additionally, rates were 25% higher among older non-Hispanic Blacks (aged 65 years or older) than older non-Hispanic Whites.3,4

Furthermore, 2009 to 2013 data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program indicate that the frequency of oral and pharyngeal cancers increases with age and that African Americans continue to fare worse than Whites in terms of five-year relative survival (with survival rates of 47% and 66%, respectively).5

A complex array of factors at multiple levels determine an individual’s oral—and overall—health status. Children without access to healthy food sources, for example, are at much higher risk for chronic diseases such as dental caries, obesity, and diabetes. A recent editorial highlights the profound impact of upstream factors such as childhood poverty on a child’s health; the editorial describes a mother who continues to give her child a bottle of milk at night even though she knows the practice contributes to the child’s obesity and severe dental caries.6 The mother is afraid that the child’s crying at night will force them from the apartment they are sharing. The recognition that poverty has a tremendous influence on children’s health has led to a new policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics7 that recommends screening family members to determine whether they lack basic needs, such as food, housing, and heat, and providing referrals to community services to assist families in economic stress.

ORAL HEALTH DISPARITIES RESEARCH

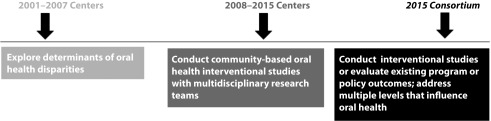

The support of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) in the area of oral health disparities research has been a long-term, strategic investment to build a solid foundation of knowledge that can inform clinical practice and public policies (Figure 1). For almost two decades, NIDCR’s strategic plans have addressed its commitment to eliminating oral health disparities, and the Institute’s disparities research program was established in part to address the US Surgeon General’s 2000 oral health report findings. The first phase of the program began in 2001, with five Centers for Research to Reduce Oral Health Disparities and a number of investigator-initiated studies. NIDCR-supported investigators conducted descriptive studies focused on children and their caregivers to define levels of disease across populations, as well as investigations into a broader array of factors that influence an individual’s oral health status.

FIGURE 1—

Support of Oral Health Disparities Research: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Centers and Consortium

These studies led to randomized controlled trials within the second program phase, which targets modifiable factors believed to be important drivers of oral health. Tailored oral health interventions have been tested in community-based settings such as Project Head Start centers, county health departments, federally qualified health centers, Native American reservations, public housing units, primary care offices, and WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) clinics. Importantly, the studies have been designed and implemented with community input and active involvement, with an overall goal of uncovering practical, sustainable approaches to improving the oral health of diverse underserved populations.

In the past 15 years, NIDCR-funded researchers have established that individual factors such as one’s genetic makeup, oral health literacy and behaviors, geographic distance to a dentist, and oral microbiome characteristics may influence oral health status, in addition to traditional factors such as socioeconomic status. These findings have led to a more sophisticated conceptualization of the etiology of oral diseases and factors contributing to oral health disparities. It is now understood that factors associated with disparities are numerous and complex, existing at levels ranging from the individual to society, as well as from the biological to health system and policy levels. For example, having medical providers screen and refer young children with dental caries will not succeed in reducing caries if the population has limited access to or knowledge of dental providers willing to care for those with public insurance.

Recognizing that factors at multiple levels determine an individual’s oral health status, NIDCR launched a new initiative in 2015: the Multidisciplinary and Collaborative Research Consortium to Reduce Oral Health Disparities in Children. The initiative called for studies that take a holistic approach to promoting health and preventing and managing disease in populations of children facing health disparities and inequities. Studies funded through the program address a range of determinants of oral health and risk factors at varied levels of influence, such as individual biological and behavioral factors and organizational or institutional factors within communities and health care systems.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There is an increasing need to support interdisciplinary research aimed at identifying, understanding, and addressing population-level health disparities that influence aging and older adults’ health.8 Certain segments of the older adult population may be disproportionately affected by poor oral health outcomes, such as those with restricted access to quality care because of socioeconomic status, racial/ethnic discrimination in health care settings, insurance status, overall health status, or functional status. The National Institute on Aging and NIDCR encourage researchers in the aging and oral health disparities disciplines to explore partnerships and form interdisciplinary research collaborations to address oral health disparities among older adults. Future research directions may identify means of increasing access to prevention and quality treatment earlier in the life span to offset the cumulative effects of environmental, sociocultural, and behavioral determinants of oral health disparities over the life course.

After more than 15 years of funding research on oral health disparities, NIDCR remains committed to eliminating such disparities. NIDCR plans to launch a strategic initiative called “NIDCR 2030,” a set of bold visionary goals to achieve by the year 2030, to ensure that our research endeavors embrace integrated approaches to addressing research questions; promoting evidence-based, cost-effective health care and prevention strategies; overcoming health disparities, including those related to oral health; facilitating a diverse workforce; and enhancing engagement and partnerships with existing stakeholders and broader communities. Interwoven throughout these goals is an emphasis on promoting research that helps overcome health disparities and inequities and stimulates affordable and accessible prevention and treatment options for people with dental, oral, and craniofacial diseases and disorders.

NIDCR anticipates launching NIDCR 2030 in spring 2017, at which time the Institute will encourage diverse scientific and nonscientific communities to submit ideas on how to achieve its goals. Public responses and workshops will guide the development of high-risk, high-reward initiatives that will enable NIDCR to reach its 2030 vision: ensuring that the institute remains a leader in research innovation and that health disparities and inequities are integrated into its overall research goals.

Footnotes

See also Borrell, p. S6.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Available at: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/Documents/hck1ocv.@www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86(5):611–622. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla TJ. Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;191:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dye B, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla T. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;197:197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2013. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013. Accessed December 21, 2016.

- 6.Klass P. Saving Tiny Tim—pediatrics and childhood poverty in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(23):2201–2205. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1603516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill CV, Perez-Stable EJ, Anderson NA, Bernard MA. The National Institute on Aging Health Disparities Research Framework. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(3):245–254. doi: 10.18865/ed.25.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]