Abstract

Medical students require a strong foundation in normal histology. However, current trends in medical school curricula have diminished time devoted to histology. Thus, there is a need for more efficient methods of teaching histology. We have developed a novel software program (Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource; https://pcs-webtest0.pathology.washington.edu/academics/pattern/) that uses annotated whole slide images to teach normal histology. Whole slide images of a wide variety of tissues were annotated by a trainee and validated by an experienced pathologist. Still images were extracted and transferred to the Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource web application. In Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource, an image was displayed briefly and the user was forced to identify the tissue type. The display time changed inversely based on cumulative accuracy to challenge the user and maintain engagement. A total of 129 second-year medical students completed the 30-minute Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource module. Surveys showed an increase in confidence from premodule (0% extremely confident, 4% very, 47% somewhat, and 49% not) to postmodule (9% extremely confident, 57% very, 32% somewhat, and 2% not), P < .0001. Accuracy increased from 72.6% pretest to 95.7% posttest, P < .002. The effect size (Cohen d = 2.30) was very large, where 0.2 is a small effect, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large. Ninety-six percent of students would recommend Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource to other medical students, and 98% would use Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource to further enhance their histology knowledge. Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource drastically improved medical student accuracy in classifying normal histology and improved confidence. Additional study is needed to determine knowledge retention, but Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource has great potential for efficient teaching of histology given the curriculum time constraints in medical education.

Keywords: digital pathology, e-learning, histology, informatics, medical education

Introduction

Histology forms the foundation of human biology, and a strong background in histology is essential for studying pathology. Medical school curricula have traditionally taught normal histology during the “preclinical” or “basic science” years. Competing pressures on curricula have forced many medical schools to reduce the amount of time dedicated to normal histology. Historical surveys have shown a decrease in classroom time dedicated to normal histology, from 160 hours in the 1950s to an average of 73 hours in 2009.1 This trend is expected to continue given the reduced time devoted to basic science with the shift toward integrated courses.2 For example, at our home institution, the basic science “years” now comprise a total of 15 months of instruction. In addition, the curriculum lacks a dedicated normal histology course and time at the microscope.

Many residency programs, in particular pathology, feel the negative consequences of decreased normal histology preparation during medical school.3 The Association of Pathology Chairs has identified a gap in histology knowledge among incoming residents and has highlighted the difficulty in remediating this gap during training given the already tight time constraints in residency.4 Thus, curriculum time constraints necessitate innovative methods for teaching normal histology.5 Recently, virtual microscopy has eliminated the need for expensive slide sets and microscopes while simultaneously increasing the accessibility and efficiency of pathology education for students.6,7 Longitudinal surveys have shown an increase in use of virtual microscopy, from 14% of students in 2002 to 44% in 2009.1 This shift has been well received by students who prefer virtual microscopy over conventional microscopy for its efficiency and independence.8,9 A concurrent expansion in the available number of online images has created the opportunity for further innovations.10

We developed an educational software program called Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource (NDER) that takes advantage of a large database of images. The NDER uses still images extracted from annotated whole slide images (WSIs) and engages users with an adaptive learning algorithm to improve trainees’ “fast thinking” skills. We hypothesized that NDER would increase diagnostic accuracy, confidence, and interest in normal histology among a cohort of second-year medical students at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Materials and Methods

Module Development

WSIs of a wide variety of tissues chosen from the University of Washington Pathology database were annotated with regions of interest (ROIs) exemplifying normal histology. Although many of the WSIs featured pathologic processes, care was taken to select ROI that avoided areas featuring disease and instead only showed normal histology. The ROIs were validated by an experienced pathologist. Still images measuring 2000 × 2000 pixels (240 images) were extracted, transferred to a database, and used by NDER. The Normal Histology NDER module included a 20-question pretest, a 200-question training module, a 20-question posttest, and a survey. The pretest and posttest consisted of 20 images with 5 multiple-choice options. The user was given unlimited time to select tissue of origin for each image. The sequence of images was randomized to prevent recall bias from pretest to posttest. During the module, each question consisted of an image that is displayed briefly before the user is forced to identify the tissue type among 5 answer choices. The format is akin to a digital flash card followed by a 5-part multiple-choice question. Immediate feedback is given. The NDER module was adaptive such that the time an image was displayed changed based on user accuracy. Initially, the images were displayed for 4 seconds. As cumulative accuracy changed, image time adjusted with a lower limit of 1.5 seconds and an upper limit of 10 seconds. The pretest and posttest were comprised of unique images that were not used in the module. The module included 200 questions and lasted approximately 20 minutes. The total time to completion, including the pretest and posttest, was approximately 30 minutes. A results interface displaying all 240 images was shown after completion of the posttest. See our previous description for further technical details.11

Participants

Second-year medical students at the University of Washington School of Medicine voluntarily took the Normal Histology NDER module during dedicated classroom time using their personal computing devices. The second-year medical students completed a normal histology course during their first year of medical school. Pretest, posttest, and survey results were deidentified for analysis. The study was determined to be exempt by institutional review board of the University of Washington.

Statistical Analysis

Pretest and posttest scores were analyzed using a paired t test. Cohen d was used to estimate the effect size. Pretest and posttest survey results were compared using a χ2 test. A significance value of P < .05 was used for all statistical tests. Analyses were performed using the statistical software program R version 3.2.2.

Results

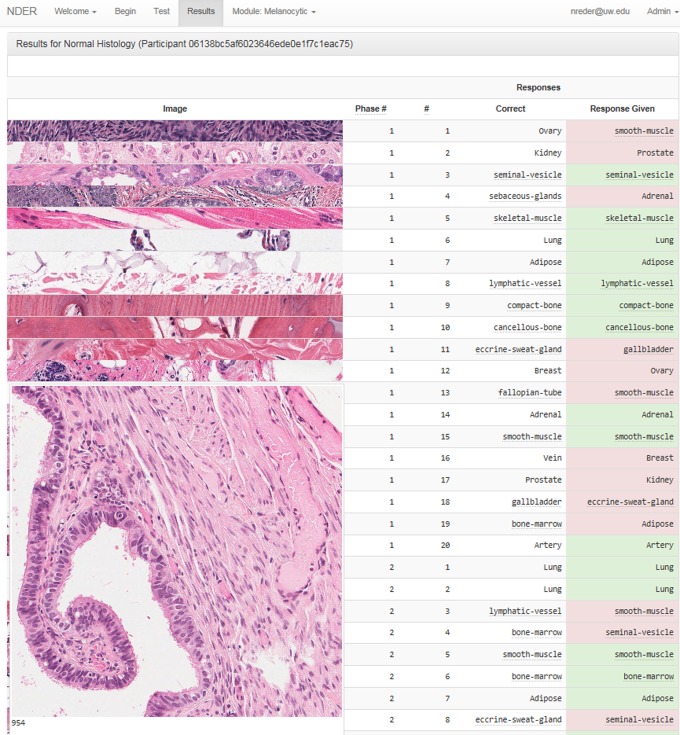

The NDER module lasted approximately 30 minutes. The module was completed by 129 of the 195 students in attendance (66% retention rate). Diagnostic accuracy increased from 72.6% pretest to 95.7% posttest (P < .0001). The effect size (Cohen d = 2.30) was very large, where 0.2 is a small effect, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large. A comparison of pretest to posttest accuracy is shown in Table 1. Students attained 100% accuracy on the majority of organs and greater than 95% accuracy on 14 of 19 organs in the posttest. Prostate was the only organ where student performance significantly decreased from pretest to posttest (skeletal muscle also showed a decline, but the difference did not reach statistical significance). A display of the results interface seen by the student after completion of the module is shown in Figure 1. Analysis of the images and discussion with the students revealed that the prostate image on the pretest contained corpora amylacea, while the image on the posttest did not have any luminal concretions, providing a possible explanation for the decrease in accuracy.

Table 1.

Overall and Organ-Specific Pretest and Posttest Scores.*

| Organ | Pretest (%) | Posttest (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Prostate | 76.0 | 56.6 |

| Seminal vesicle | 31.0 | 83.7 |

| Eccrine sweat gland | 82.2 | 91.5 |

| Adrenal | 22.5 | 93.8 |

| Skeletal muscle | 100.0 | 96.9 |

| Fallopian tube | 73.6 | 97.7 |

| Breast | 53.5 | 99.2 |

| Bone marrow | 63.6 | 99.2 |

| Ovary | 45.7 | 100.0 |

| Lymphatic vessel | 70.5 | 100.0 |

| Sebaceous gland | 76.7 | 100.0 |

| Adipose | 79.1 | 100.0 |

| Smooth muscle | 87.6 | 100.0 |

| Cancellous bone | 88.4 | 100.0 |

| Compact bone | 89.1 | 100.0 |

| Kidney | 89.9 | 100.0 |

| Artery | 95.3 | 100.0 |

| Vein | 93.0 | 100.0 |

| Lung | 99.2 | 100.0 |

| Overall | 72.6 | 95.3 |

*Student pretest diagnostic accuracy as compared to posttest diagnostic accuracy by tissue type and overall performance. This reveals increased diagnostic accuracy in every tissue type except prostate and an increase in overall diagnostic accuracy from 72.6% to 95.3%.

Figure 1.

Results interface. A screenshot of the Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource (NDER) results interface. Thumbnail images of every question in the pretest, module, and posttest are displayed along with the response given by the student and the correct answer. The student can expand the thumbnail image of each question for further study of the relevant histologic features.

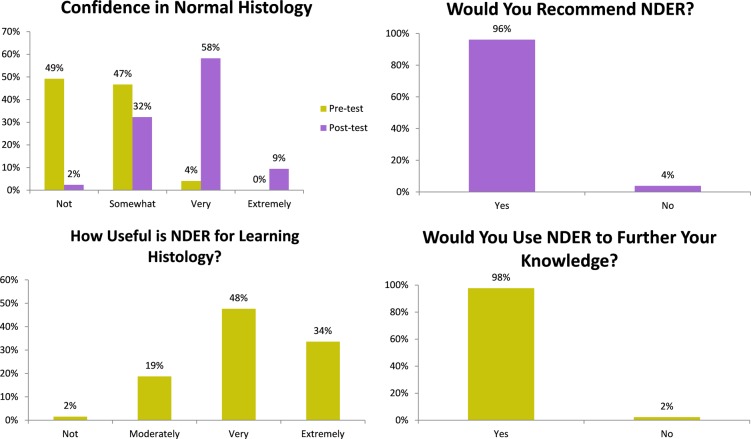

Surveys (Figure 2) showed a significant increase in confidence from premodule (0% extremely confident, 4% very, 47% somewhat, and 49% not) to postmodule (9% extremely confident, 57% very, 32% somewhat, and 2% not, P < .0001). The overwhelming majority (80%) of students found NDER to be useful for learning histology. Ninety-six percent of students would recommend NDER to other medical students, and 98% would use NDER to further enhance their histology knowledge. Anecdotal qualitative feedback was positive with many students reporting that the NDER module motivated them to explore additional histology resources.

Figure 2.

Survey results. Students found that Novel Diagnostic Educational Resource (NDER) was useful for learning normal histology and increased their diagnostic confidence. The majority of students would recommend NDER and would use NDER again.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that our normal histology software module significantly increased diagnostic accuracy among a cohort of second-year medical students. Survey results showed increased confidence and a willingness to use NDER for further study of histology, which we used as surrogate methods to assess interest. Anecdotal qualitative feedback indicated that many students were motivated to explore additional histology resources after completing the NDER module. Given that participation in NDER was entirely voluntary and without incentive, the survey results are felt to be reflective of true sentiment and unbiased. The module lasts approximately 30 minutes and can be completed anywhere on any device with an Internet connection and a Google account (https://pcs-webtest0.pathology.washington.edu/academics/pattern/).

Methods for teaching normal histology in medical school have remained relatively consistent over the past century, with the major change being a shift from conventional microscopy to virtual microscopy.1,7 Virtual microscopy is well received by students8,9 and integrates well into medical school curricula.12,13 Yet, given the dwindling time and resources dedicated to normal histology, additional advances are needed for students to learn the same amount of material, if not more, in less time. Medical education, including normal histology, focuses almost exclusively on the analytic processes, a deliberate rule-based method of solving a problem or arriving at a diagnosis.14 For instance, students learning normal histology may be given an example photomicrograph of an ovary with an explanation of key features that lead to identification of the organ. This style of learning is excellent for conceptual topics but inefficient for topics involving pattern recognition. In fact, pattern recognition by experts often occurs in the preattentive stage, arriving at an answer in less than 200 milliseconds.15 Ark et al demonstrated that a combined approach of rule-based and pattern recognition improved electrocardiogram diagnostic accuracy compared to either method on its own.14 In this study, we have shown a method for increasing medical student pattern recognition, which can be combined with traditional methods to increase the efficiency of normal histology instruction. Inclusion of tissue physiology in future teaching modules may also be a valuable addition to the learning module, as this will elevate the learning process from pattern recognition to “system 2” thinking, involving reasoning.16 Addition of “slow” or methodical learning through future online physiology and pathology tutorials may have a synergistic effect on learning.

Limitations of the study include a single time point comparison, a study population of second-year medical students who had previously completed a normal histology course in their first year. We will have the opportunity to test NDER on naive medical students in the coming school year. Reliance on still images rather than dynamic WSIs leaves open the question of whether the medical students could have identified the salient features of the tissues on their own.17 However, the NDER module uses still images in an engaging active format, and the adaptive, time-limited, game-like environment of NDER is the source of its utility and novelty. A comparison of NDER versus passive learning using still images, versus learning using WSIs, may be an appropriate topic for a future study. Finally, our brief NDER module demonstrated a large short-term effect, but the duration of the effect cannot be ascertained from our study design. Further studies should be performed to quantify test–retest retention, the duration of knowledge retention, the effect of the module on normal histology-naive students, and translation of the results to WSI.

In conclusion, we have described a normal histology module that drastically increases diagnostic accuracy during an engaging 30-minute session. Additional study is needed to determine knowledge retention, but NDER has great potential for efficient teaching of histology given the curriculum time constraints in modern-day medical student education.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Elizabeth U. Parker and Nicholas P. Reder contributed equally to this manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Drake RL, McBride JM, Lachman N, Pawlina W. Medical education in the anatomical sciences: the winds of change continue to blow. Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2:253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar K, Indurkhya A, Nguyen H. Curricular trends in instruction of pathology: a nationwide longitudinal study from 1993 to present. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:1147–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pratt RL. Are we throwing histology out with the microscope? A look at histology from the physician’s perspective. Anat Sci Educ. 2009;2:205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Talbert ML, Ashwood ER, Brownlee NA, et al. ; College of American Pathologists; Association of Pathology Chairs. Resident preparation for practice: a white paper from the College of American Pathologists and Association of Pathology Chairs. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1139–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drake RL. A retrospective and prospective look at medical education in the United States: trends shaping anatomical sciences education. J Anat. 2014;224:256–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dee FR. Virtual microscopy in pathology education. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1112–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamilton PW, Wang Y, McCullough SJ. Virtual microscopy and digital pathology in training and education. APMIS. 2012;120:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Helle L, Nivala M, Kronqvist P, Gegenfurtner A, Björk P, Säljö R. Traditional microscopy instruction versus process-oriented virtual microscopy instruction: a naturalistic experiment with control group. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marchevsky AM, Relan A, Baillie S. Self-instructional “virtual pathology” laboratories using web-based technology enhance medical school teaching of pathology. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trelease RB. From chalkboard, slides, and paper to e-learning: how computing technologies have transformed anatomical sciences education. Anat Sci Educ. 2016;9:583–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reder NP, Glasser D, Dintzis SM, et al. NDER: a novel web application using annotated whole slide images for rapid improvements in human pattern recognition. J Pathol Inform. 2016;7:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Craig FE, McGee JB, Mahoney JF, Roth CG. The virtual pathology instructor: a medical student teaching tool developed using patient simulator software. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1985–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kumar RK, Freeman B, Velan GM, De Permentier PJ. Integrating histology and histopathology teaching in practical classes using virtual slides. Anat Rec B New Anat. 2006;289:128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ark TK, Brooks LR, Eva KW. Giving learners the best of both worlds: do clinical teachers need to guard against teaching pattern recognition to novices? Acad Med. 2006;81:405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Healey CG, Booth KS, Enns JT. High-speed visual estimation using preattentive processing. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI). 1996;3:107. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mione S, Valcke M, Cornelissen M. Remote histology learning from static versus dynamic microscopic images. Anat Sci Educ. 2016;9:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]